Beyond Metabolism: Psychiatric and Social Dimensions in Bariatric Surgery Candidates with a BMI ≥ 50—A Prospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

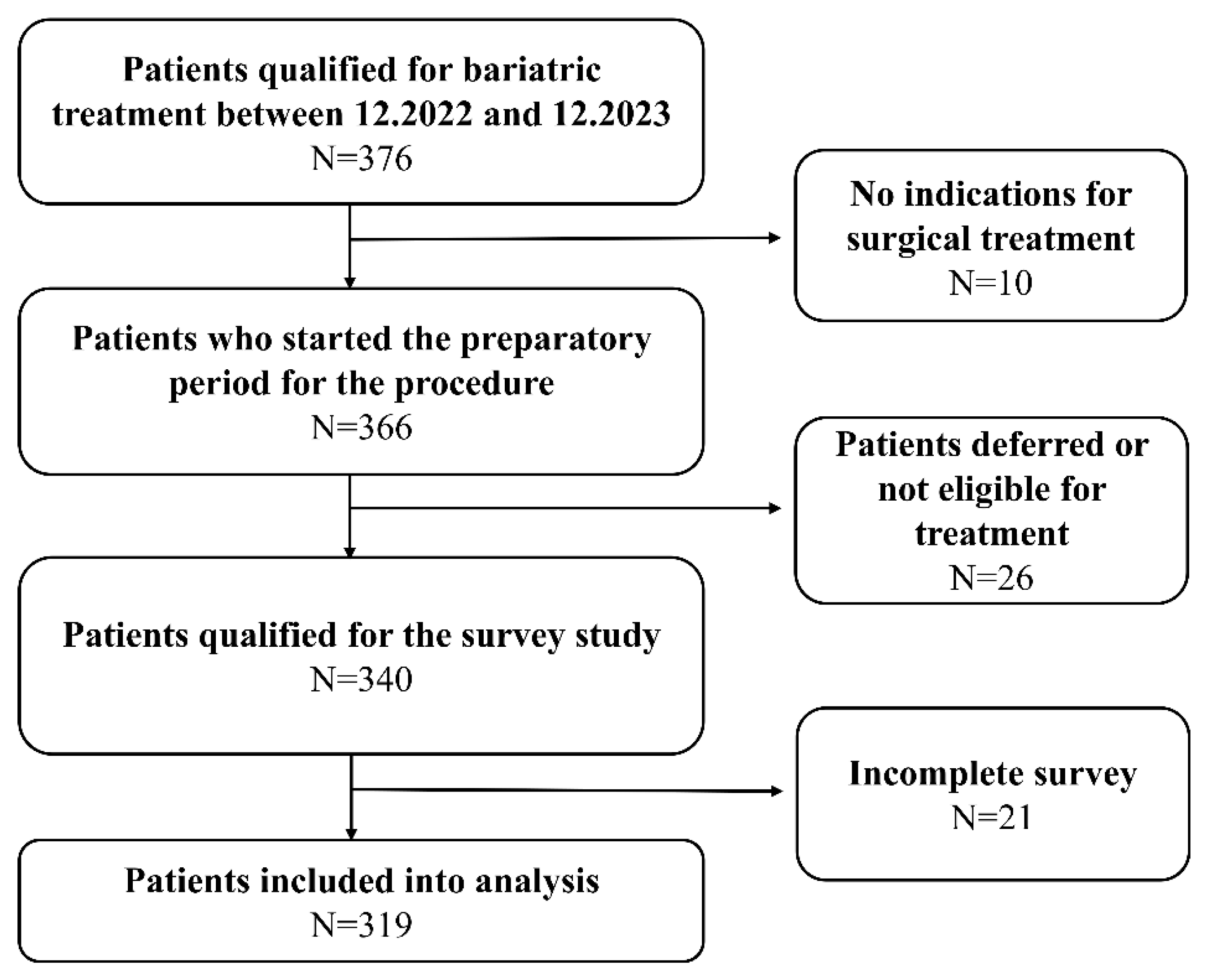

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Group Characteristics

3.2. Comorbidities and Laboratory Examination

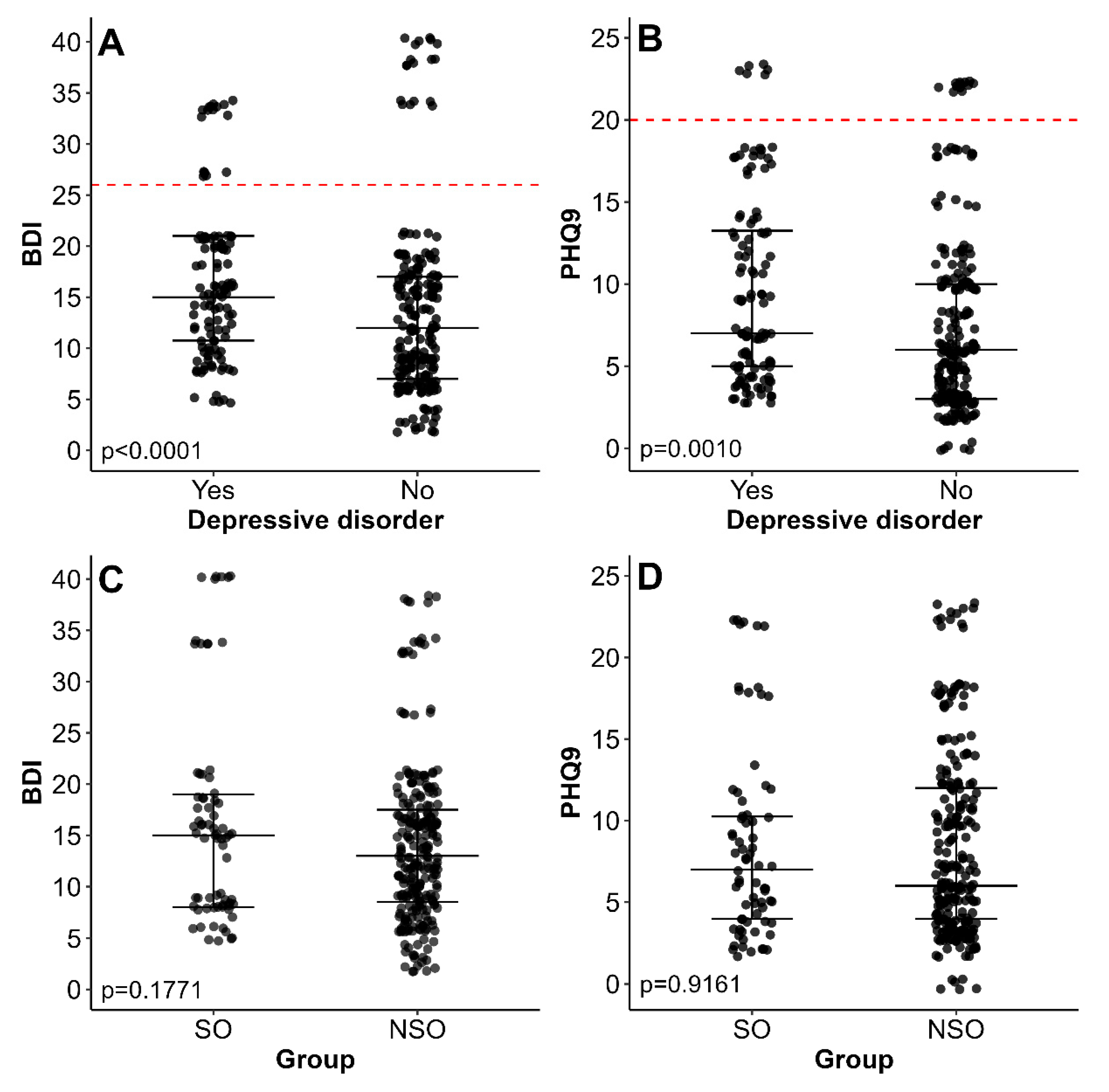

3.3. Mental Health and Psychiatric History

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heymsfield, S.B.; Wadden, T.A. Mechanisms, Pathophysiology, and Management of Obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturm, R.; Hattori, A. Morbid obesity rates continue to rise rapidly in the United States. Int. J. Obes. 2013, 37, 889–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poirier, P.; Giles, T.D.; Bray, G.A.; Hong, Y.; Stern, J.S.; Pi-Sunyer, F.X.; Eckel, R.H. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: Pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss: An update of the 1997 American Heart Association Scientific Statement on Obesity and Heart Disease from the Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation 2006, 113, 898–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahel, P.; Sud, S.K.; Lee, S.J.; Jackson, T.; Urbach, D.R.; Okrainec, A.; Allard, J.P.; Bassett, A.S.; Paterson, A.D.; Sockalingam, S.; et al. Phenotypic and genetic analysis of an adult cohort with extreme obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2019, 43, 2057–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obesity Prevention and Treatment Overwhelmed the System—Supreme Audit Office. Available online: https://www.nik.gov.pl/en/news/obesity-prevention-and-treatment-overwhelmed-the-system.html (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Yáñez, M.; Vargas, G. Monogenic, Polygenic and Multifactorial Obesity in Children: Genetic and Environmental Factors. Austin J. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 4, 1052. [Google Scholar]

- Telles, S.; Gangadhar, B.N.; Chandwani, K.D. Lifestyle Modification in the Prevention and Management of Obesity. J. Obes. 2016, 2016, 5818601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajewska, D.; Lange, E.; Kęszycka, P.; Białek-Dratwa, A.; Gudej, S.; Świąder, K.; Giermaziak, W.; Kostelecki, G.; Kret, M.; Marlicz, W.; et al. Recommendations on dietary treatment of obesity in adults: 2024 position of the Polish Society of Dietetics. J. Health Inequalities 2024, 10, 22–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulconbridge, L.F.; Bechtel, C.F. Depression and Disordered Eating in the Obese Person. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2013, 3, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connell, J.; Kieran, P.; Gorman, K.; Ahern, T.; Cawood, T.J.; O’Shea, D. BMI ≤ 50 kg/m2 is associated with a younger age of onset of overweight and a high prevalence of adverse metabolic profiles. Public. Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 1090–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Marek, R.J.; Williams, G.A.; Mohun, S.H.; Heinberg, L.J. Surgery type and psychosocial factors contribute to poorer weight loss outcomes in persons with a body mass index greater than 60 kg/m2. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2017, 13, 2021–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abiri, B.; Hosseinpanah, F.; Banihashem, S.; Madinehzad, S.A.; Valizadeh, M. Mental health and quality of life in different obesity phenotypes: A systematic review. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2022, 20, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milaneschi, Y.; Simmons, W.K.; van Rossum, E.F.C.; Penninx, B.W. Depression and obesity: Evidence of shared biological mechanisms. Mol. Psychiatr. 2019, 24, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiwanmall, S.A.; Kattula, D.; Nandyal, M.B.; Devika, S.; Kapoor, N.; Joseph, M.; Paravathareddy, S.; Shetty, S.; Paul, T.V.; Rajaratnam, S.; et al. Psychiatric Burden in the Morbidly Obese in Multidisciplinary Bariatric Clinic in South India. Indian. J. Psychol. Med. 2018, 40, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruger-Steyn, W.M.; Lubbe, J.; Louw, K.A.; Asmal, L. Depressive symptoms and quality of life prior to metabolic surgery in Cape Town, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Psychiatr. 2022, 28, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lykouras, L. Psychological profile of obese patients. Dig. Dis. 2008, 26, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belloli, A.; Saccaro, L.F.; Landi, P.; Spera, M.; Zappa, M.A.; Dell’Osso, B.; Rutigliano, G. Emotion dysregulation links pathological eating styles and psychopathological traits in bariatric surgery candidates. Front. Psychiatr. 2024, 15, 1369720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCuen-Wurst, C.; Ruggieri, M.; Allison, K.C. Disordered eating and obesity: Associations between binge eating-disorder, night-eating syndrome, and weight-related co-morbidities. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1411, 96, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrósio, G.; Kaufmann, F.N.; Manosso, L.; Platt, N.; Ghisleni, G.; Rodrigues, A.L.S.; Rieger, D.K.; Kaster, M.P. Depression and peripheral inflammatory profile of patients with obesity. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018, 91, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | SMO N = 72 | NSMO N = 247 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age [years] | 41 (34–50) | 34 (29–43) | <0.0001 |

| Body mass (highest) [kg] | 154.5 (145–176.25) | 128 (119–136.5) | <0.0001 |

| Body mass (present) [kg] | 149.5 (138.75–166.25) | 122 (112–132) | <0.0001 |

| Height [cm] | 170 (165–180) | 170 (165–177) | 0.6067 |

| BMI (highest) [kg/m2] | 51.77 (50.93–54.59) | 44.79 (42.14–46.92) | <0.0001 |

| BMI (present) [kg/m2] | 50.62 (49.57–53.2) | 43.07 (40.45–45.28) | - |

| Variable | SMO N = 72 | NSMO N = 247 | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 19 (26.39%) | 49 (19.84%) | 1.45 (0.74–2.76) | 0.2324 |

| Female R | 53 (73.61%) | 198 (80.16%) | |||

| Employment | Unemployed | 26 (36.11%) | 69 (27.94%) | 1.46 (0.80–2.62) | 0.1900 |

| Employed R | 46 (63.89%) | 178 (72.06%) | |||

| Higher degree | Yes | 29 (40.28%) | 86 (34.82%) | 1.26 (0.71–2.23) | 0.4056 |

| No R | 43 (59.72%) | 161 (65.18%) | |||

| Relationship status | Single | 12 (16.67%) | 46 (18.62%) | 0.87 (0.40–1.81) | 0.7048 |

| In relationship R | 60 (83.33%) | 201 (81.38%) | |||

| Marital status | Formal relationship/Marriage | 40 (66.67%) | 75 (37.31%) | 3.36 (1.82–6.17) | 0.0001 |

| Informal relationship | 20 (33.33%) | 126 (62.69%) | |||

| Lifelong obesity | Yes | 55 (76.39%) | 102 (41.3%) | 4.58 (2.45–8.92) | <0.0001 |

| No R | 17 (23.61%) | 145 (58.7%) | |||

| Family history of obesity | Yes | 71 (98.61%) | 217 (87.85%) | 9.78 (1.57–405.33) | 0.0054 |

| No R | 1 (1.39%) | 30 (12.15%) | |||

| Higher degree of parents | Yes | 16 (22.22%) | 101 (40.89%) | 0.41 (0.21–0.78) | 0.0036 |

| No R | 56 (77.78%) | 146 (59.11%) | |||

| Violence against child | Yes | 36 (50%) | 52 (21.05%) | 3.73 (2.07–6.76) | <0.0001 |

| No R | 36 (50%) | 195 (78.95%) | |||

| Variable | SMO N = 72 | NSMO N = 247 | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart attack | Yes | 4 (5.56%) | 7 (2.83%) | 2.01 (0.42–8.19) | 0.2762 |

| No R | 68 (94.44%) | 240 (97.17%) | |||

| Stroke | Yes | 3 (4.17%) | 3 (1.21%) | 3.52 (0.46–26.85) | 0.1310 |

| No R | 69 (95.83%) | 244 (98.79%) | |||

| Fatty liver disease | Yes | 69 (95.83%) | 229 (92.71%) | 1.81 (0.5–9.85) | 0.4296 |

| No R | 3 (4.17%) | 18 (7.29%) | |||

| Chronic venous insufficiency | Yes | 46 (63.89%) | 4 (1.62%) | 104.11 (34.34–428.85) | <0.0001 |

| No R | 26 (36.11%) | 243 (98.38%) | |||

| Hypertension | Yes | 57 (79.17%) | 128 (51.82%) | 3.52 (1.85–7.07) | 0.0004 |

| No R | 15 (20.83%) | 119 (48.18%) | |||

| Obstructive sleep apnoea | Yes | 70 (97.22%) | 147 (59.51%) | 23.67 (6.06–203.12) | <0.0001 |

| No R | 2 (2.78%) | 100 (40.49%) | |||

| Diabetes | Yes | 31 (43.06%) | 107 (43.32%) | 0.99 (0.56–1.74) | >0.9999 |

| No R | 41 (56.94%) | 140 (56.68%) | |||

| Variable | SMO N = 72 | NSMO N = 247 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| AST [U/l] | 118.5 (100.75–134) | 58 (48–76) | <0.0001 |

| ALT [U/l] | 121 (99–134) | 68 (56–88) | <0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol [mg/dL] | 438.5 (348–562) | 332 (268–402) | <0.0001 |

| HDL [mg/dL] | 39 (37–41) | 42 (39–45) | <0.0001 |

| Triglycerides [mg/dL] | 268.5 (208–357.25) | 211 (189–286) | <0.0001 |

| HbA1c [%] | 5.6 (5.5–6.53) | 5.8 (5.6–5.9) | 0.4313 |

| CRP [mg/dL] | 11.2 (7.8–14.3) | 6.5 (4.9–11.15) | <0.0001 |

| Fasting glucose [mg/dL] | 98 (89.75–129) | 100 (95–106.5) | 0.5786 |

| Insulin [uU/mL] | 27.5 (23–40) | 21 (17–26) | <0.0001 |

| HOMA-IR | 8.14 (5.38–10.38) | 5.19 (3.95–7.01) | <0.0001 |

| Variable | SMO N = 72 | NSMO N = 247 | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of psychiatric treatment | Yes | 15 (20.83%) | 121 (48.99%) | 0.28 (0.14–0.52) | <0.0001 |

| No R | 57 (79.17%) | 126 (51.01%) | |||

| Current psychiatric treatment | Yes | 10 (13.89%) | 57 (23.08%) | 0.54 (0.23–1.15) | 0.1019 |

| No R | 62 (86.11%) | 190 (76.92%) | |||

| Depressive disorder | Yes | 13 (18.06%) | 99 (40.08%) | 0.33 (0.16–0.65) | 0.0010 |

| No R | 59 (81.94%) | 148 (59.92%) | |||

| No R | 70 (97.22%) | 226 (91.5%) | |||

| Nocturnal eating syndrome | Yes | 30 (41.67%) | 119 (48.18%) | 0.77 (0.43–1.35) | 0.3500 |

| No R | 42 (58.33%) | 128 (51.82%) | |||

| Binge eating disorder | Yes | 29 (40.28%) | 169 (68.42%) | 0.31 (0.17–0.55) | <0.0001 |

| No R | 43 (59.72%) | 78 (31.58%) | |||

| Bulimia | Yes | 10 (13.89%) | 37 (14.98%) | 0.92 (0.38–2.01) | >0.9999 |

| No R | 62 (86.11%) | 210 (85.02%) | |||

| Number of eating disorders | ≥1 | 39 (54.17%) | 199 (80,57%) | 0.29 (0.16–0.50) | <0.0001 |

| <1 | 33 (45.83%) | 48 (19.43%) | |||

| Subjective sleep quality | Poor | 50 (69.44%) | 127 (51.42%) | 2.14 (1.19–3.95) | 0.0071 |

| Good R | 22 (30.56%) | 120 (48.58%) | |||

| Prolonged sleep latency (>1 h) | Yes | 21 (29.17%) | 61 (24.7%) | 1.25 (0.66–2.32) | 0.4469 |

| No R | 51 (70.83%) | 186 (75.3%) | |||

| Nocturnal awakenings (>2/night) | Yes | 45 (62.5%) | 122 (49.39%) | 1.7 (0.97–3.05) | 0.0604 |

| No R | 27 (37.5%) | 125 (50.61%) | |||

| Early morning awakenings | Yes | 7 (9.72%) | 34 (13.77%) | 0.68 (0.24–1.64) | 0.4289 |

| No R | 65 (90.28%) | 213 (86.23%) | |||

| Snoring | Yes | 66 (91.67%) | 118 (47.77%) | 11.95 (4.95–35.02) | <0.0001 |

| No R | 6 (8.33%) | 129 (52.23%) | |||

| Hypnotic medications | Yes | 1 (1.39%) | 24 (9.72%) | 0.13 (0.00–0.84) | 0.0222 |

| No R | 71 (98.61%) | 223 (90.28%) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Herstowska, M.; Myśliwiec, K.; Bandura, M.; Chrzanowski, J.; Burzyński, J.; Michalak, A.; Lejk, A.; Karamon, I.; Fendler, W.; Kaska, Ł. Beyond Metabolism: Psychiatric and Social Dimensions in Bariatric Surgery Candidates with a BMI ≥ 50—A Prospective Cohort Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2573. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17152573

Herstowska M, Myśliwiec K, Bandura M, Chrzanowski J, Burzyński J, Michalak A, Lejk A, Karamon I, Fendler W, Kaska Ł. Beyond Metabolism: Psychiatric and Social Dimensions in Bariatric Surgery Candidates with a BMI ≥ 50—A Prospective Cohort Study. Nutrients. 2025; 17(15):2573. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17152573

Chicago/Turabian StyleHerstowska, Marta, Karolina Myśliwiec, Marta Bandura, Jędrzej Chrzanowski, Jacek Burzyński, Arkadiusz Michalak, Agnieszka Lejk, Izabela Karamon, Wojciech Fendler, and Łukasz Kaska. 2025. "Beyond Metabolism: Psychiatric and Social Dimensions in Bariatric Surgery Candidates with a BMI ≥ 50—A Prospective Cohort Study" Nutrients 17, no. 15: 2573. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17152573

APA StyleHerstowska, M., Myśliwiec, K., Bandura, M., Chrzanowski, J., Burzyński, J., Michalak, A., Lejk, A., Karamon, I., Fendler, W., & Kaska, Ł. (2025). Beyond Metabolism: Psychiatric and Social Dimensions in Bariatric Surgery Candidates with a BMI ≥ 50—A Prospective Cohort Study. Nutrients, 17(15), 2573. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17152573