Abstract

Background: The current food system is unsustainable, making it essential to address the issue globally through adequate policies and sustainable development goals. The European Union aims to dedicate 25% of farmland to organic farming by 2030 to promote sustainable practices. Warsaw is the first Polish city working on an urban sustainable food policy; however, there is limited data on the sustainable food system (SFS) and organic sector available. Objectives: This research examines whether consumers in Warsaw who prefer organic food also display other sustainable characteristics and awareness, reflected in their food choices, dietary habits, and other food-related behaviors. Methods: A household survey (HHS) was conducted as part of the SysOrg project, focusing on evaluating the sustainability of food systems in Warsaw in the areas of diet and organic food. The clusters of respondents, grouped by the self-declared proportion of organic foods in their diets, were analyzed and compared, and in addition, correlation analyses of the share of organic food in diets and other sustainability parameters were performed. Results: The study of 449 respondents indicates that Warsaw is at an early stage of the organic transformation, with the largest group of respondents declaring a 1–10% share of organic products in their diet. There were significant differences in dietary choices, sustainability awareness, and food selection habits and motivations among various consumer groups depending on their organic food share. Conclusions: Overall, this study’s findings highlight a link between organic food consumption and certain sustainable behaviors, suggesting potential for organic consumers’ contribution to a sustainable transformation. The study offers valuable insights into the existing knowledge gap regarding the behaviors of organic and sustainable consumers in Warsaw. Furthermore, despite the non-random nature of the sample limiting the generalizability of findings, it serves as a preliminary resource for other European cities that are formulating food policies and incorporating Green Public Procurement (GPP) into their procurement processes, especially for municipalities within the Visegrad Group.

1. Introduction

The unsustainability of current food systems has resulted in significant environmental consequences, including land degradation, habitat and biodiversity loss, and the pollution of water, soil, and air [1]. Additionally, these systems contribute to negative health outcomes, such as malnutrition, obesity, and various non-communicable diseases [2,3]. In response to these and many other globally pressing issues, the United Nations (UN) has established the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a roadmap for promoting global sustainability [4,5,6]. An immediate outcome of this political initiative has been the incorporation of the 2030 Agenda goals into the national policies of UN member states. The European Union (EU) has formulated a strategy through the adoption of the Green New Deal, which includes the Common Agricultural Policy [7,8]. This strategic framework aims to increase the proportion of organic agriculture to 25% by 2030 across the EU [9]. As an EU member state, Poland is mandated to “more than double its agricultural area under organic farming by 2030” [10]. While the organic sector is acknowledged for its contributions to the three dimensions of sustainable food systems (SFSs)—social, environmental, and economic [11]—it remains relatively minor in Poland, exhibiting stagnant dynamics. Currently, 4.4% of Poland’s total agricultural land is used for organic farming, in contrast to the EU average of 10.9% [12]. Furthermore, the distribution of organic farmland and operators within Poland is uneven [13].

Warsaw, the capital city of Poland, along with other postsocialist capitals in Central Europe that are part of the Visegrad Group (V4), such as Prague, Budapest, and Bratislava, aims to reach the economic and social standards of the wealthiest countries in Northern and Western Europe. In this year’s Financial Times ranking of “European Cities & Regions of the Future”, Warsaw is maintaining its leading position among Central and Eastern European cities, making its urban transformation a valuable example for other emerging cities [14,15]. It is also the first Polish city to sign and adopt the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact (MUFPP) [16]. The city is actively engaged in developing an urban food policy aimed at sustainable food management to ensure food security, reduce food waste, and promote sustainable consumption [17]. Sustainable food consumption (SFC) is a consumer-driven, holistic concept that encompasses the integrated implementation of sustainable patterns in food consumption and production while respecting the carrying capacities of natural ecosystems. This includes, among others, encouraging plant-rich diets, limiting meat consumption, and choosing sustainable agricultural practices [18,19]. In 2019, only 9% of adults in Poland reported consuming the recommended five portions of fruits and vegetables daily (below the EU average of 12%) [20], and in 2023, the daily consumption of fruits and vegetables reached about 280 g per capita (with the European Union average of 685 g per capita) [21]. Concurrently, meat consumption has steadily increased, reaching 79.2 kg per person annually by 2022 [22,23]. Organic consumption, which constitutes a part of SFC [24], remains relatively low in Poland, with individuals spending on average EUR 8 per capita annually on certified organic food. In comparison, in Switzerland, the country with the highest per capita expenditures on organic food, it is EUR 468 per person per year—a large distinction, even when factoring in higher earnings [12]. The organic market, being a niche market, is similar across all the V4 group countries, with comparable consumer behaviors regarding the purchase of organic food [15]. However, the situation is dynamic, as policies are evolving and cities are establishing strategic sustainable frameworks, e.g., sustainable public procurement [25].

The SysOrg project, titled “Organic Agro-Food Systems as Models for Sustainable Food Systems in Europe and Northern Africa”, aims to characterize and analyze five specific territorial cases, namely the Warsaw municipality in Poland, the North Hessia region in Germany, the Cilento bio-district in Italy, the Kenitra province in Morocco, and the Copenhagen municipality in Denmark, with the aim to identify pathways for enhancing sustainable and organic consumption and food production. Next to perspectives such as food system transitions, sustainable and healthy diets, and food waste problems, it investigates key areas related to organic food and farming–agricultural systems that have tangible contributions to environmental protection and resource conservation through, i.e., water protection, carbon storage, ecosystem service resilience, biodiversity protection, and GHG emissions reduction [26,27,28].

As for Warsaw, there is a dearth of data regarding the residents’ sustainable organic consumption and behaviors. This paper seeks to provide a preliminary overview of organic consumption patterns based on the household survey (HHS) study sample in the capital city. It also aims to explore whether individuals with higher levels of organic consumption demonstrate higher sustainability awareness and more sustainable behaviors regarding their dietary choices compared to those who do not engage in organic consumption.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection: Household Survey

The household survey applied in this study was developed by the international SysOrg project consortium [29] to collect comprehensive data on three key sustainability perspectives addressed in the project, which are diet, organic food consumption, and food waste in different SysOrg case territories. The present study focuses on the territory of Warsaw and takes into consideration a range of HHS aspects, including socio-demographic information, the frequency of food consumption (including organic food), the proportion of organic foods in participants’ diets, shopping behaviors, perceptions of sustainability and organic products, and food choice determinants. Certain questions were derived from previously validated questionnaires [30,31,32]. The selected questions from the survey are reported in the Supplementary Materials (Table S1). The HHS, administered using Lime Survey© (https://www.limesurvey.org/) was distributed through the river sampling methodology (a non-probabilistic approach to recruiting respondents online) [33] by diverse social media channels (e.g., Facebook, Instagram) and online sites (e.g., Municipality of Warsaw). To reach respondents from 18 districts of Warsaw, the survey was circulated through the online communication channels of different neighborhoods of the city. Altogether, 484 adults (>18 years old) completed the survey, and after data cleaning (a process aiming to develop one standardized dataset for the results of the SysOrg household survey for all 5 case study territories excluding respondents speeding and with incomplete answers), the responses of 449 Warsaw residents were included in further analyses. The characteristics of the included respondents are presented in Appendix A. Previous research has displayed additional characteristics of the study group [29].

Data collection was conducted in compliance with the European Commission’s General Data Protection Regulation (679/2016), and the study followed the ethical guidelines set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki [34]. All participants provided informed consent for the use of their responses in the anonymously completed HHS. The research protocol received approval from the Scientific Research Ethics Committee at the Institute of Human Nutrition Sciences of the Warsaw University of Life Sciences (approval number: 50/2021; date: 15 November 2021).

At the outset of the survey, participants were instructed to ensure that it was completed by the adult individual primarily responsible for food preparation and purchasing within the household. Analytical methods were employed to explore associations between the self-reported share of organic food in respondents’ diets (0%, 1–10%, 11–25%, 26–50%, 51–75%, 76–99%, and 100%) and the responses to questions pertinent to healthy and sustainable behaviors. Considering the distribution of the surveyed population in terms of the declared share of organic food in the diet, some results were presented in four groups, namely the 0%, 1–10%, 11–25%, and 26–100% groups.

2.2. Data Analysis

The following descriptive statistics were utilized to characterize the study sample: the number of observations, percentages, and means. Pearson’s chi-squared test was applied to evaluate the relationships between the qualitative variables. Associations between the quantitative variables were analyzed using Spearman correlation analysis. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant for all tests conducted. Factor analysis with a principal component extraction method was used to obtain factors defining certain dietary patterns (DPs). This statistical method helps uncover dietary patterns based on the consumption frequencies of certain food groups. In this case, it allowed us to identify distinct eating behavior profiles—such as plant-based or meat-heavy diets—based on how respondents reported their intake of various food groups. The factors were subjected to a varimax-normalized rotation. The number of factors was selected based on the following criteria: components with an eigenvalue of 1 or more, a scatter plot, and the interpretability of the factors. The selection of factors was confirmed using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s sphericity test. Bartlett’s test value was p < 0.001, and the KMO value for DPs was 0.780. Factor loadings of 0.5 or higher were used to identify factor components of certain DPs. The statistical analyses were performed using Statistica software version 13.3 PL (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA; StatSoft, Krakow, Poland).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Organic Consumption in Warsaw—Overview

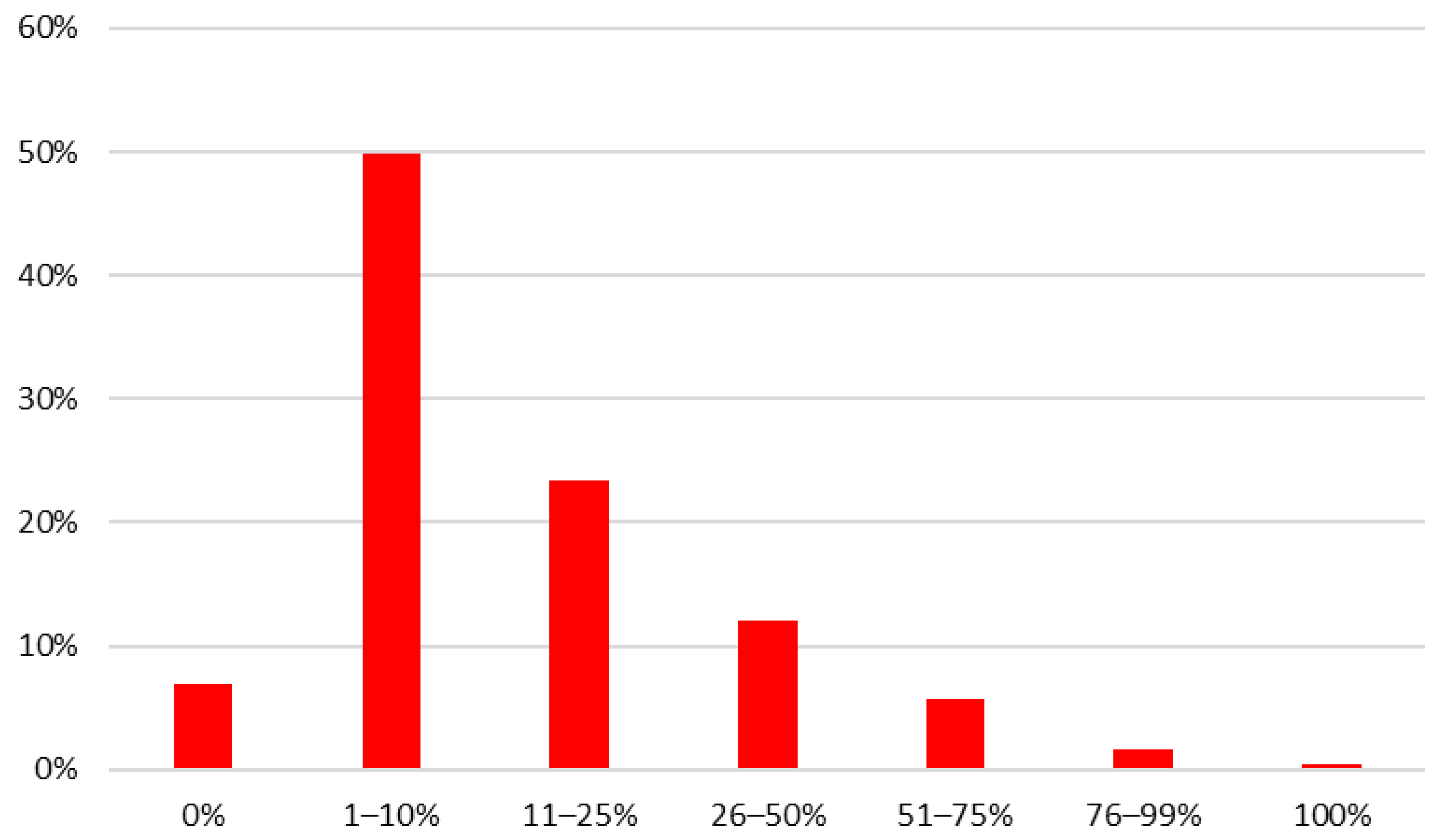

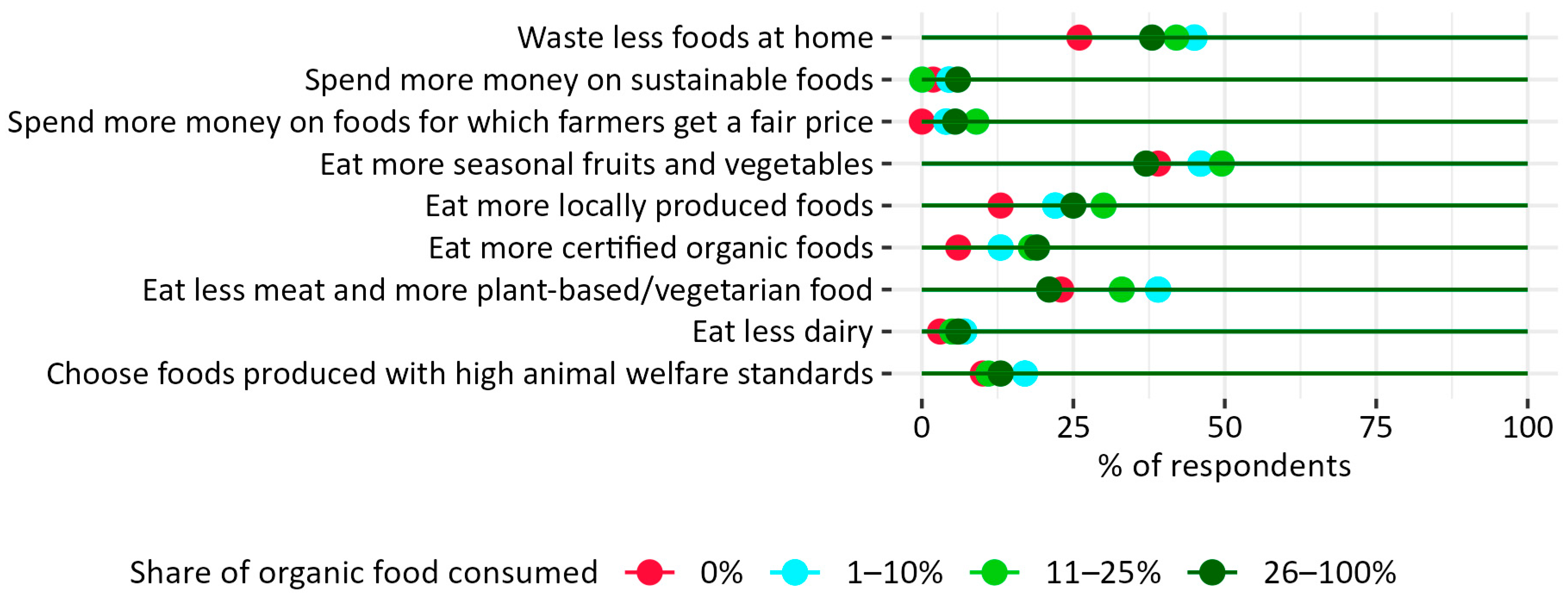

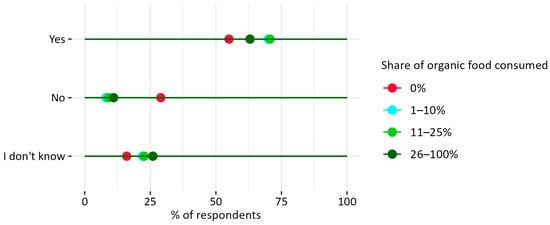

This study’s findings, based on the 449 respondents, indicate that Warsaw is still at an early stage of developing its organic food market. According to the HHS, 50% of respondents classified themselves in the low-organic consumption group (1–10%), while 7% reported consuming no organic products at all (0%). In contrast, 8% indicated high (>50%)-organic consumption (Figure 1). The low consumption of organic food in Poland has also been previously documented through the country’s research [35].

Figure 1.

Answers to the household survey question: “What percentage, by volume, of the foods you eat is organic?” by respondents in Warsaw. N = 449.

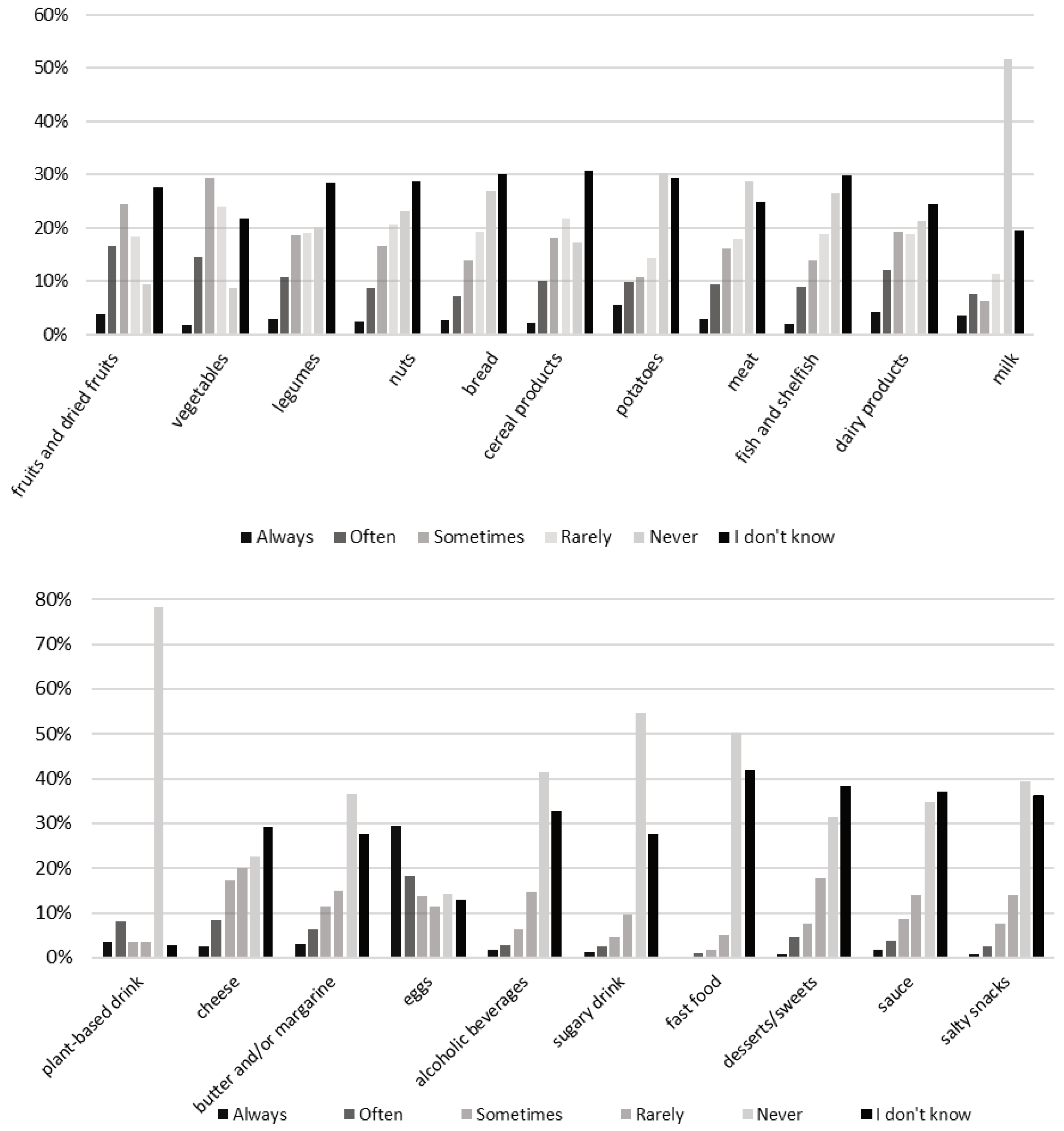

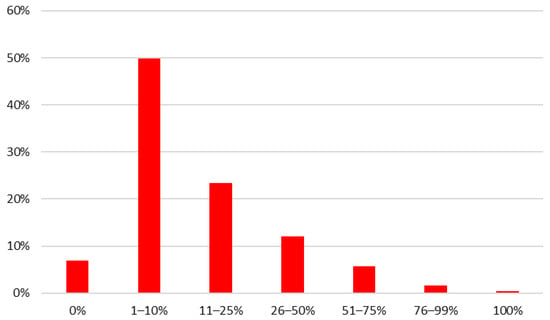

In the survey, about 20% of respondents indicated that they always or often choose organic options for vegetables, fruits, legumes, and eggs—consequently, these products are among the most frequently consumed organic items. In contrast, 78% and 53% of respondents reported that they never select organically produced plant-based drinks and milk, and 25–30% of respondents declared never opting for common staple foods, such as organic potatoes, meats, fish, or bread. Additionally, the less healthy food categories seemed to be more often consumed as conventional products, such as alcohol, sugary drinks, fast food, desserts, sweets, and salty snacks (36–55% indicated that they never opt for organic options) (see Figure 2). The preference for organic vegetables and fruits, as well as eggs, is also supported by the Farma Świętokrzyska report from 2021 [36] and further supported by findings from a study by Wojciechowska-Solis and Śmiglak-Krajewska in 2021 [37], particularly in the case of organic vegetables. Milk alternatives represent a category of products that may be unfamiliar to Polish consumers, often accompanied by less favorable associations [38,39]. Furthermore, there is a deficiency in communication and information regarding the various options available on the market [38,39], and as a result, the majority of consumers may not know about organic plant-based drink selections. As for milk, in Poland, the limited number of organic milk processors hinders the growth of the organic dairy sector [40], translating into limited market offerings, which may explain the lack of preference for organic choices in this study. However, the situation is dynamically changing in this context, since big dairy market players have recently started developing organic production lines. The low consumption of organic fast foods, sweets, and alcohol may also be connected with the low availability of organic options of these food categories in Poland [41]. Previous Danish research shows that the majority of fast-food customers want healthier and more sustainable fast food menu options; however, taste and price remain the major drivers for actual purchase decisions within this food category [42].

Figure 2.

Answers to the household survey question: “How often are the [product group] you eat certified organic?” by respondents in Warsaw. N = 449.

3.2. Associations Between Organic and Sustainable Food-Related Behaviors in Warsaw

3.2.1. Dietary Behavior

In Poland, as well as in other countries, according to the current dietary recommendations [3,43], it is advisable to reduce red meat consumption and use more plant-based protein sources, including legumes and nuts, as well as incorporating fish and eggs as an alternative [44,45]. This approach is consistent with the recommendations outlined in the Planetary Health Diet (PHD) [46] to increase the consumption of healthy foods, such as nuts, fruits, vegetables, and legumes, by more than 100%, while halving meat, processed meat, and sugar consumption for both health and environmental reasons [2].

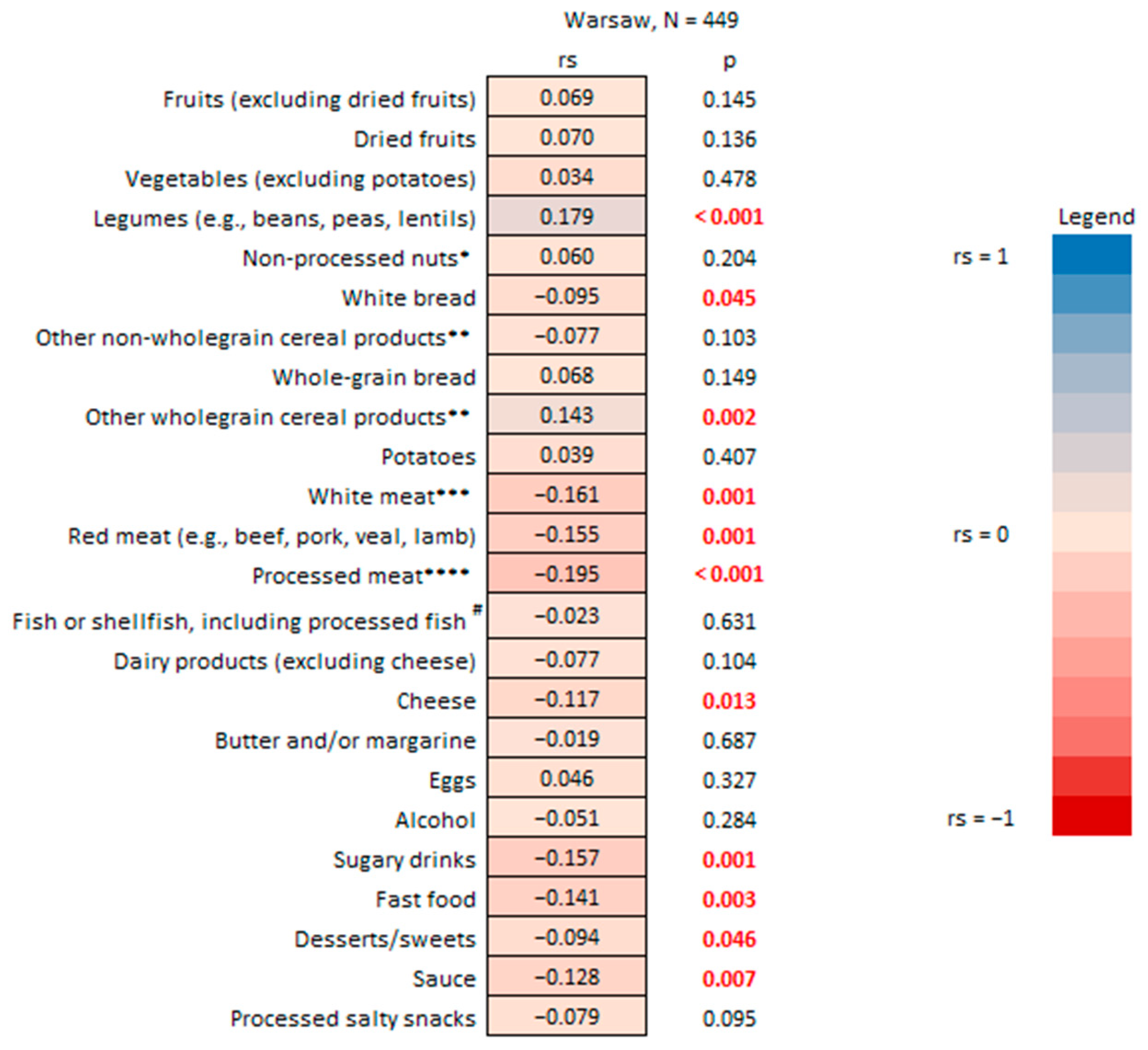

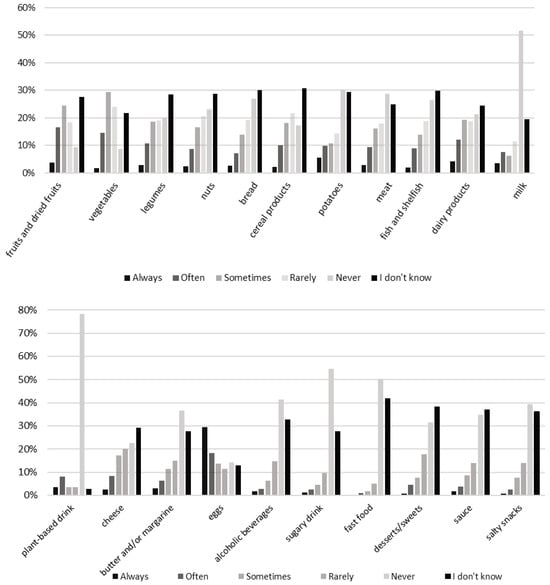

According to the findings of the present study, Warsaw HHS respondents who consume organic food tend to demonstrate a trend for healthier dietary patterns and more sustainable eating practices (Figure 3 and Figure 4). The self-reported organic food consumption was positively correlated with the frequency of consumption of legumes and whole grains. Conversely, a more limited organic food share in diets was associated with a higher frequency of meat (white, red, processed), white bread, and dessert/sweet consumption. Similarly, a negative association was noted between the consumption of organic food vs. sugary drinks and fast food—the food groups linked to a higher risk of adverse health outcomes, particularly cardiometabolic issues, and mortality [47]. The healthier dietary behavior of organic compared to non-organic consumers was also confirmed by a Polish study on diet quality indicators and organic food consumption in a group of mothers of young children [48].

Figure 3.

The organic food consumed vs. frequency of consumption of selected food product groups by household survey respondents in Warsaw. * Including peanuts (e.g., unsalted, non-roasted, not sugar-coated); ** e.g., pasta, rice; *** e.g., rabbit, chicken, turkey, other poultry; **** e.g., cured ham and turkey, salami; # e.g., canned tuna, smoked salmon. R-Spearman correlation analysis (p < 0.05).

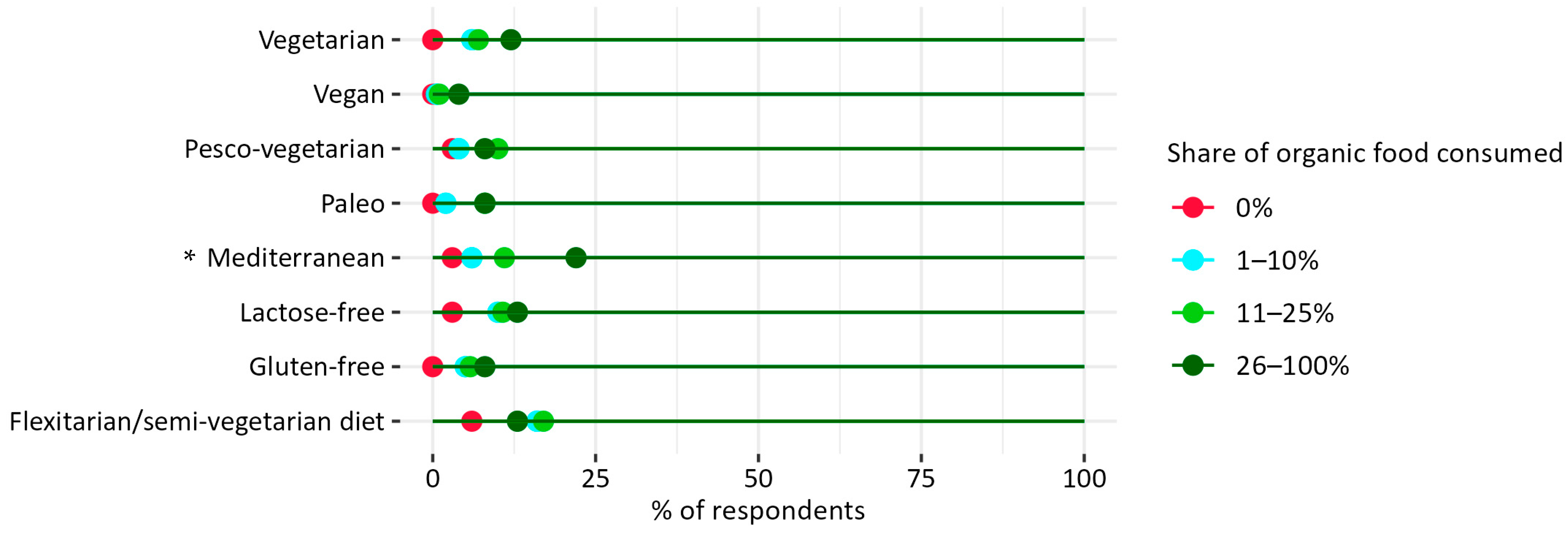

Figure 4.

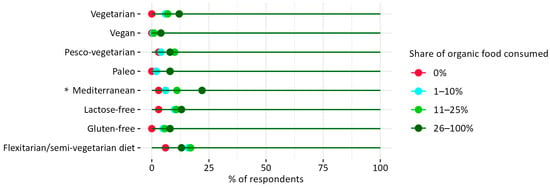

Percentage of organic food consumed vs. following a special diet by household survey respondents in Warsaw. * Pearson’s chi-squared test results for the overall relationship between variables (Chi2 = 23.27; p < 0.001). N = 449.

Respondents from the group that consumed a higher proportion of organic food (26–100%) reported more frequently that they follow a Mediterranean diet (Figure 4). This dietary pattern is recognized as beneficial for both health and environmental sustainability, especially when organic products are utilized, as they are known for being less frequently contaminated with detectable pesticide residues [49,50]. Furthermore, this diet aligns with the definition of sustainable diets proposed by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) [51] and the double food pyramid [52]. These findings are partially corroborated by recent research conducted in Spain, associating organic consumption with Mediterranean dietary patterns [53,54].

Notably, a greater number of individuals within the group reporting higher organic food share in their diet also practice vegan and vegetarian diets, which are acknowledged for their lower environmental impacts [53].

Furthermore, to identify dietary patterns (DPs), a factor analysis with a principal component extraction method was performed. The seven eating behavior patterns were identified (designated as DP1-DP7), characterized by the following factor loadings: “DP1”—characterized by the consumption of meat and eggs; “DP2”—fruits, vegetables, legumes, and unprocessed food; “DP3”—processed food and fast food; “DP4”—dairy, including cheese and butter; “DP5”—white bread and non-whole grain cereal products (e.g., pasta, rice); “DP6”—whole grain bread and other whole grain cereal products (e.g., pasta, rice); and “DP7”—alcohol (Table 1).

Table 1.

The association between organic food consumption and the identified dietary patterns (DPs) of household survey respondents in Warsaw. N = 449.

The research reveals a positive statistically significant association between a healthier, environmentally friendly, plant-based dietary pattern (DP2)—which prioritizes the consumption of fruits, vegetables, and legumes—and higher levels of organic food consumption (Table 1). Conversely, a negative correlation was identified between organic food consumption and primarily animal-based patterns such as DP1 (meat and eggs), DP4 (dairy, including cheese and butter), and DP3 (processed and fast food products). This is supported by a French study showing that the dietary share of plant-based foods increased with the contribution of organic foods to the diet, whereas a reverse trend was identified for meats and processed meats, dairy products, cookies, fast-food, and soda [55]. Furthermore, in the same study, higher organic food consumption was associated with better adherence to NDGs, which aligns with findings from other studies from Denmark [56].

3.2.2. Sustainability Awareness, Food Choice Determinants, Associations with Organic Food, and Shopping Places

Previous studies have exposed that sustainability awareness is a significant motivator for purchasing organic foods, with concerns about pesticide use, environmental degradation, and health implications driving consumer behavior [57,58].

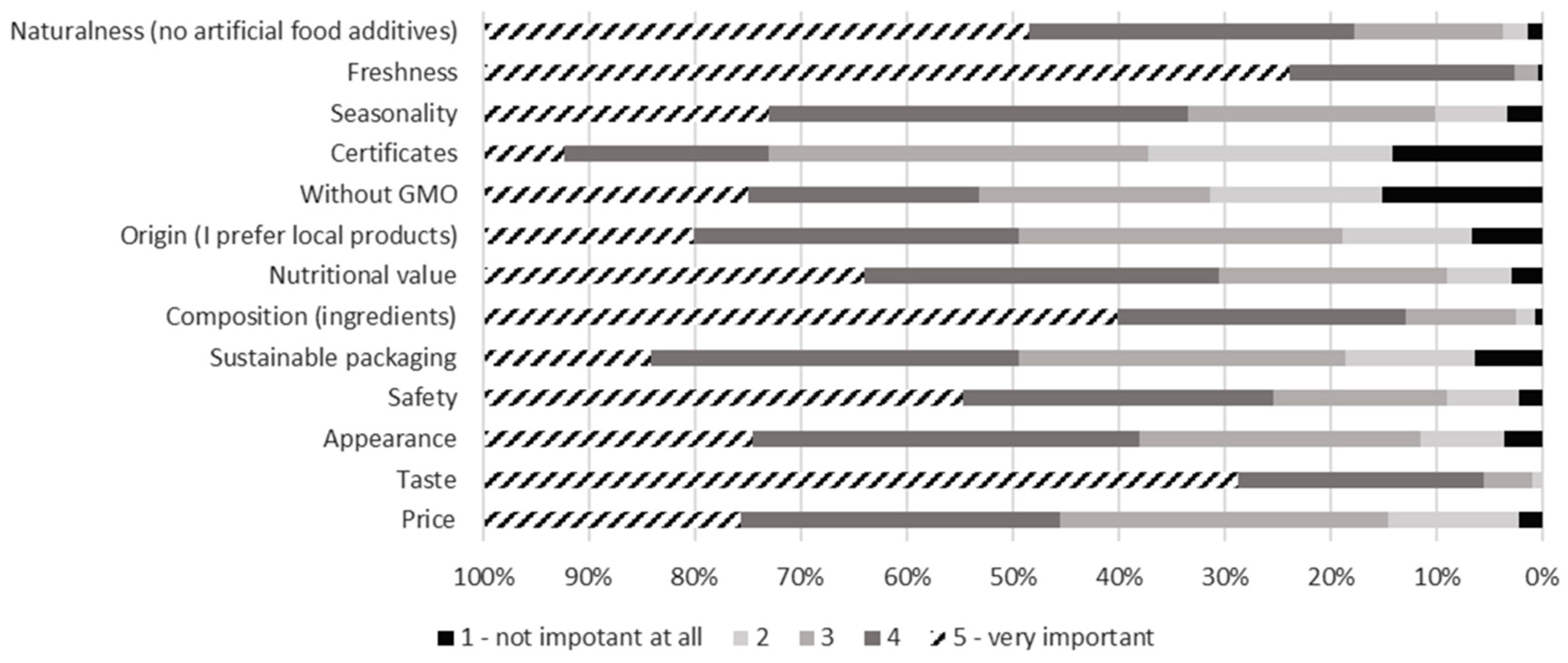

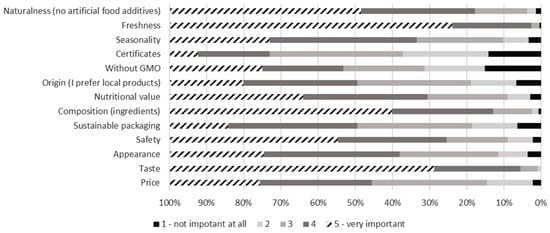

In addition, the other studies show that the capital city of Warsaw, which possesses the largest and most competitive market in Poland [59], alongside one of the highest per capita incomes in the country [60], reveals specific consumer behavior patterns. In comparison to other cities in Poland, 64% of Warsaw residents spend more than the national average on food shopping, and the city has experienced the lowest impact of inflation on food expenditures [61]. The same report [55] highlights that the inclination to opt for higher-quality products is a contributing factor to this trend. In fact, freshness, taste, and composition, alongside naturalness, no GMOs, and safety, were identified as the most significant factors influencing food purchasing decisions among Warsaw consumers in this study (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Answers to the household survey question: “How important are the following attributes for your food choices?” by respondents in Warsaw. Grading from 1—not important at all, to 5—very important. N = 449.

This is corroborated by findings from another Polish study [62] indicating that freshness and ingredient quality are paramount considerations for food shopping in the capital. However, the Report on the Study of Shopping and Eating Habits of Warsaw Residents in the Context of Food Waste [63] emphasizes the importance of price as a determining factor in food choice. In the context of this study, the attribute of price was deemed highly important by only 5% of respondents. Conversely, a substantial 25% of participants identified it as the attribute they considered not important at all (Figure 5). It is worth mentioning that the highest income group also represented the largest portion of respondents in the current survey, accounting for 24% (see Appendix A).

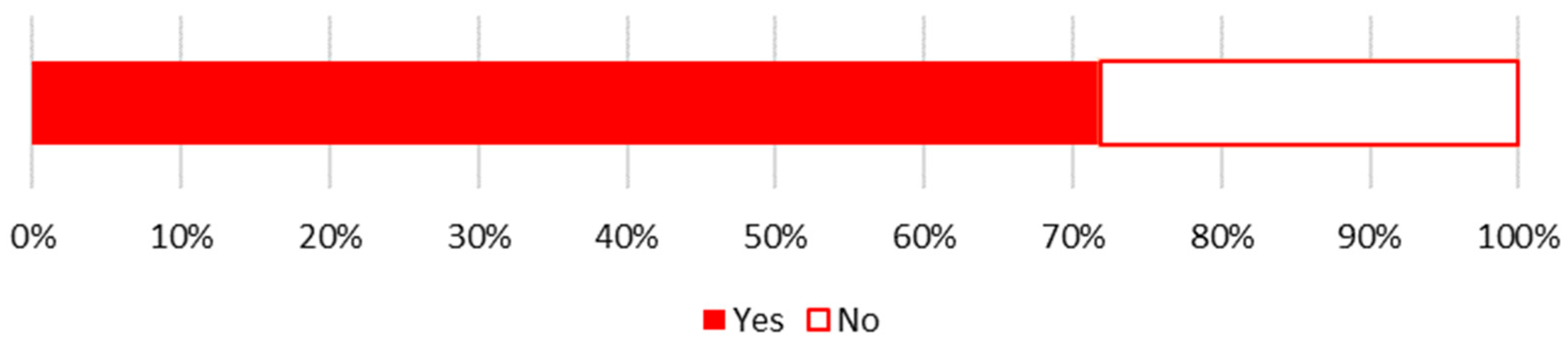

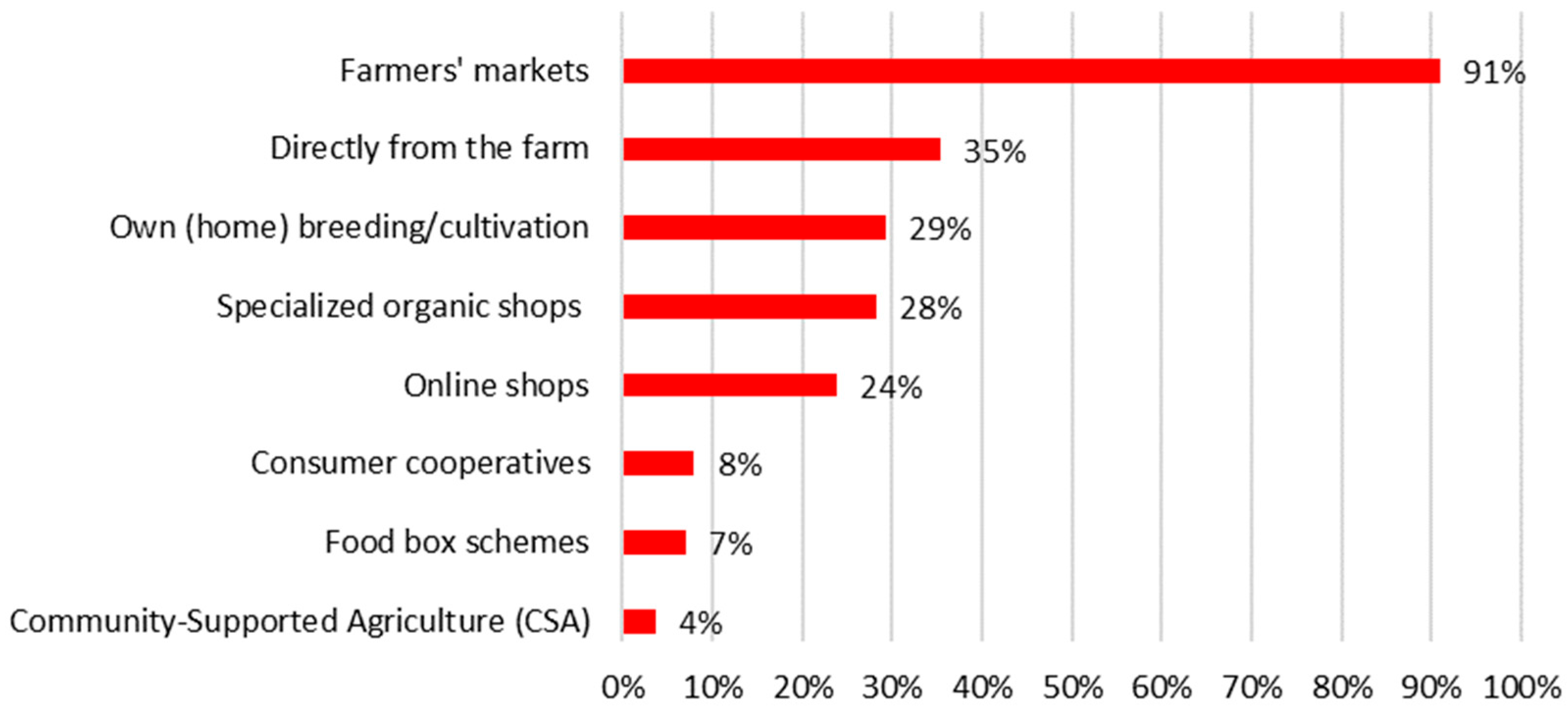

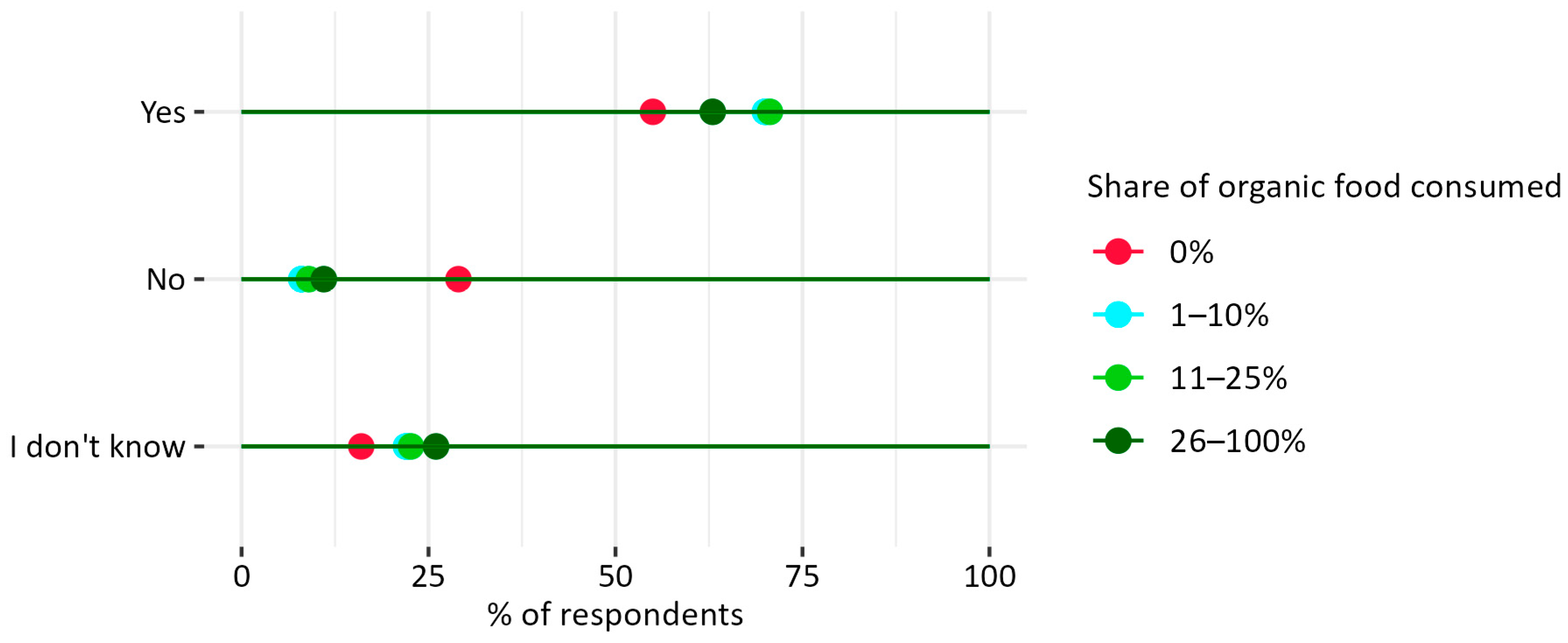

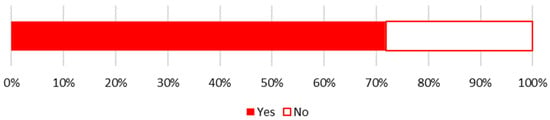

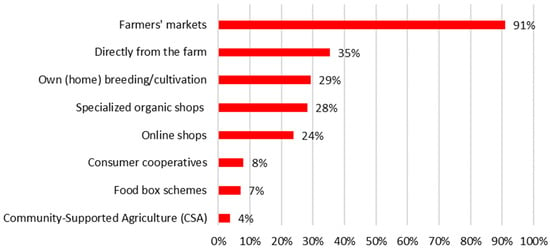

The three attributes referenced above (freshness, taste, and composition) may elucidate why over 70% of respondents declared to be engaged in sustainable shopping behaviors (Figure 6). Farmers’ markets emerge as the most favored source for procuring food outside of supermarkets, with 91% of those respondents indicating this preference (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Answers to the household survey question: “Do you obtain food from sources other than supermarkets, such as farmers’ markets, food box programs, community-supported agriculture (CSA)?” by respondents in Warsaw. N = 449.

Figure 7.

Answers to the household survey question: “In which of the initiatives and alternative places do you source your food?” by respondents in Warsaw. N = 323 (only those respondents who admitted that they obtain food from sources other than supermarkets).

Engaging in more sustainable shopping practices, particularly through the use of farmers’ markets, has been shown to be associated with a growing dissatisfaction with globalized food supply systems. This dissatisfaction often stems from concerns regarding the traceability and transparency of production processes, as well as perceived deficiencies in food quality [64]. It is also motivated by the related environmental concerns of city-dwellers, like ecological footprint and food miles—the distance food travels from production to the consumer [65].

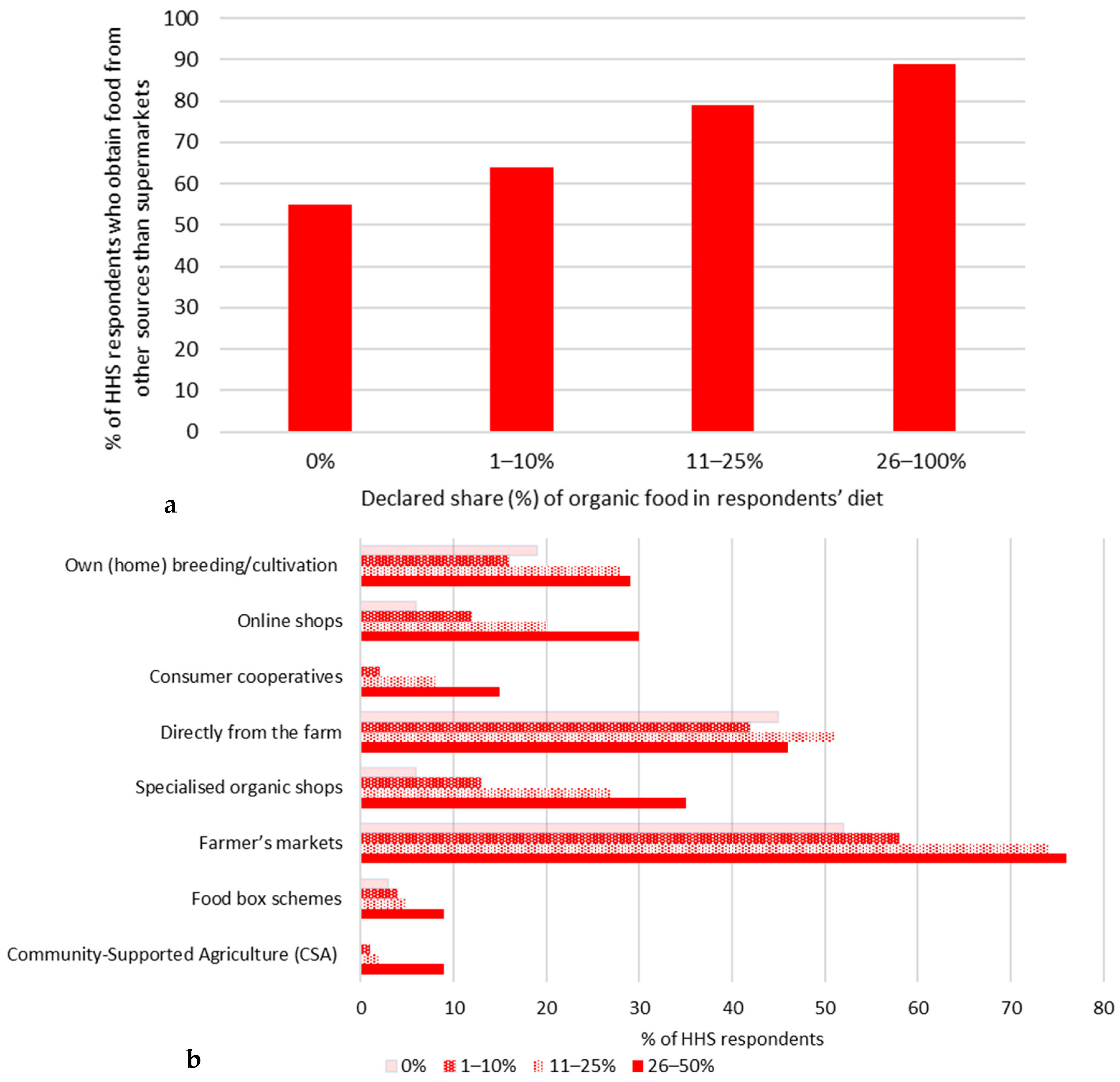

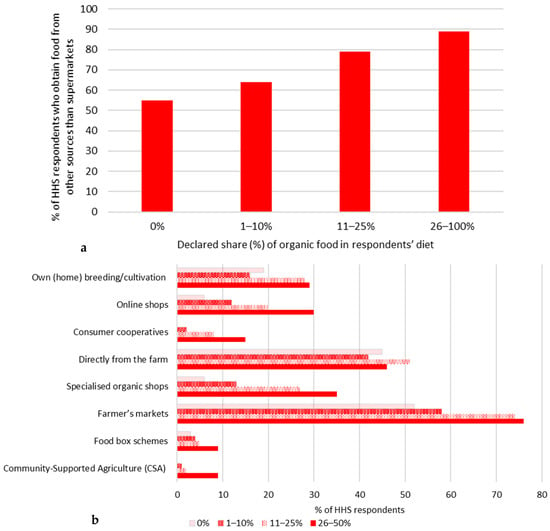

This research indicates that the group consuming the highest percentage of organic food tends to procure their provisions from sources other than supermarkets more frequently than those with lower organic consumption (Figure 8a). Moreover, the respondents from this group indicate more often that they acquire their products from a variety of the alternative venues mentioned, especially farmers markets; however, respondents declaring 11–25% share of organic food in their diet tend to be more actively involved in direct farm purchases (Figure 8b).

Figure 8.

(a) Answers to the household survey question: “Do you obtain food from sources other than supermarkets, such as farmers’ markets, food box programs, community-supported agriculture (CSA)?” vs. declared share of organic food (%). (b) Answers to the household survey question: “In which of the initiatives and alternative places do you source your food?” vs. declared share of organic food. N = 323 (only those respondents who admitted that they obtain food from sources other than supermarkets).

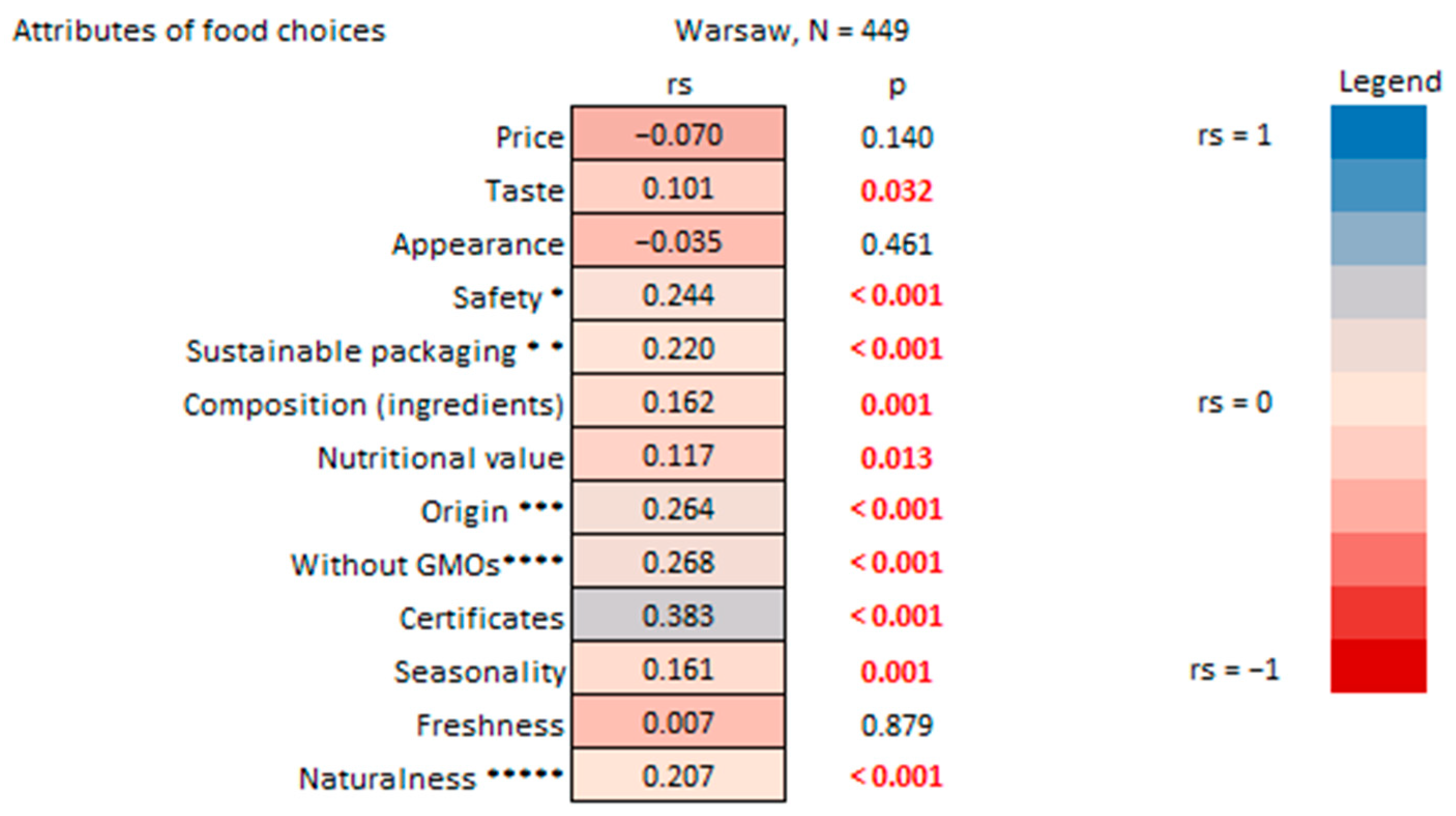

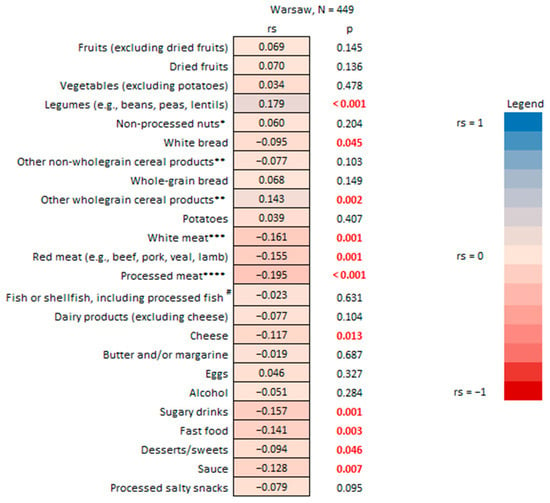

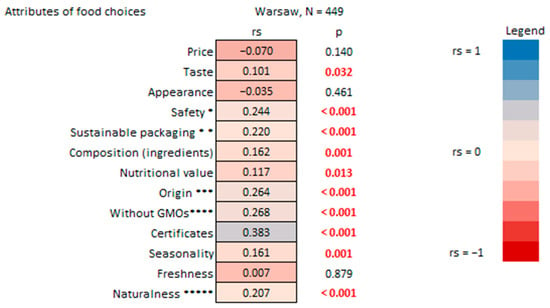

Moreover, this study reveals that higher levels of organic food consumption are linked to a greater focus on sustainable and healthy attributes in food selection. A statistically significant positive correlation was identified between the reported percentage of organic food in respondents’ diets and the importance of certifications for their food choices (Figure 9). Furthermore, there were significant positive correlations between organic consumption and preferences for “without GMO” products, as well as local products. While the environmental concerns associated with GMOs are widely discussed and increasingly acknowledged [66], choosing local products can bolster local economies and encourage sustainable agricultural practices [67]. Additionally, there was a positive correlation between organic consumption and sustainable packaging practices and food seasonality.

Figure 9.

Percentage of organic food consumed by household survey respondents in Warsaw vs. attributes of their food choices. * e.g., pathogens, pesticide residue; ** e.g., biodegradable, reusable, non-plastic; *** I prefer local products; **** genetically modified organisms; ***** no artificial food additives. R-Spearman correlation analysis (p < 0.05).

The importance of food safety (cf. pathogens, pesticide residues) as an attribute impacting food choices also demonstrated a statistically significant positive correlation with the percentage of organic food consumed (Figure 9). Additionally, nutritional value, naturalness (no artificial food additives), and composition (ingredients) also proved a statistically significant positive correlation with organic consumption.

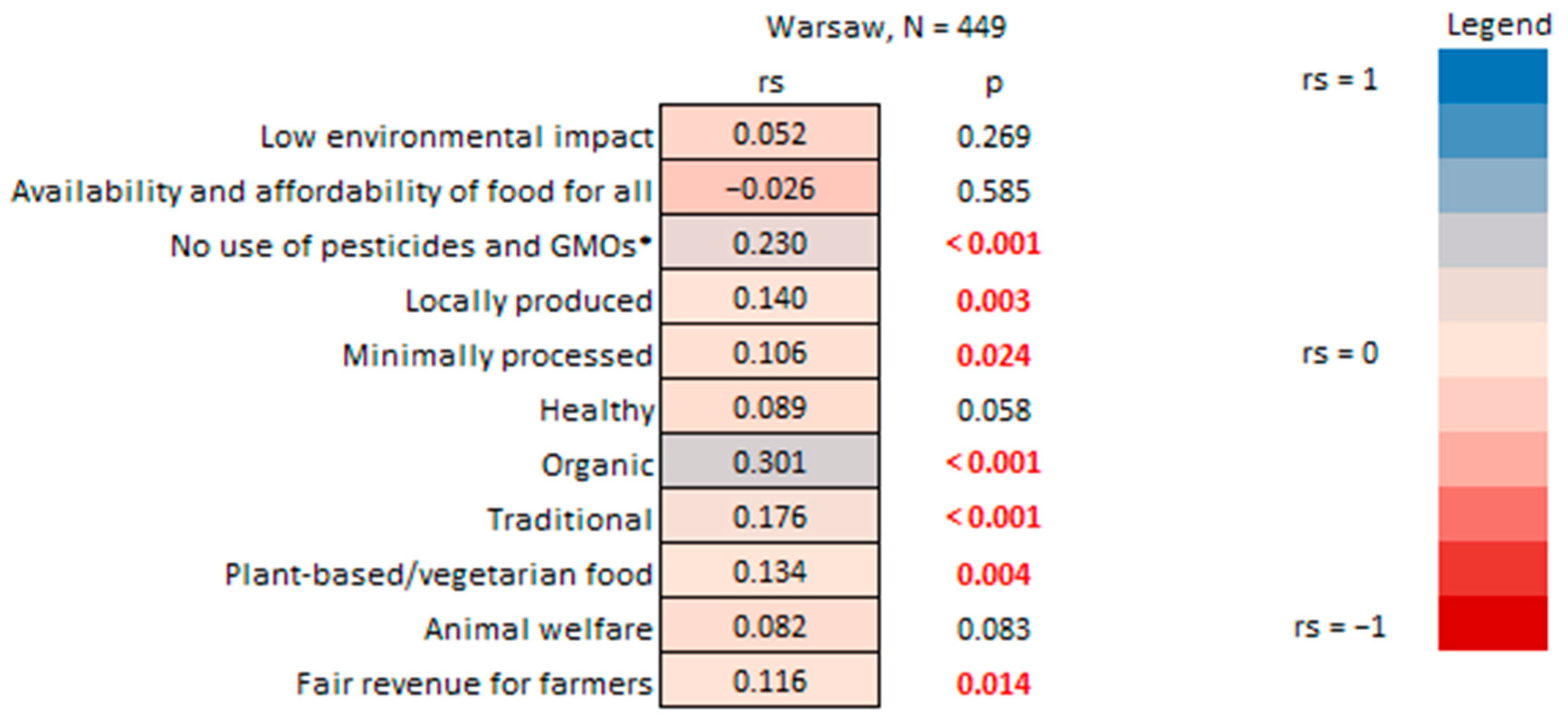

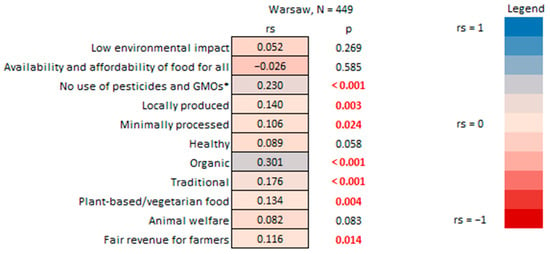

Correspondingly, respondents consuming more organic food rated significantly higher the importance of aspects of “sustainable food” such as food being organic, with no use of pesticides and GMOs, as well as food that is traditional, locally produced, minimally processed, healthy, and plant-based and provides fair revenue for farmers (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Answers to the household survey question: “How important are these aspects when you think about “sustainable” food?” vs. the percentage of organic food consumed by household survey respondents in Warsaw. * GMOs—genetically modified organisms. R-Spearman correlation analysis (p < 0.05).

The two abovementioned results (Figure 9 and Figure 10) align with findings from another Polish study that explored the connection between higher environmental awareness and the inclination to purchase organic products, highlighting concerns for the environment, the absence of harmful substances in food production, and a low level of processing [68].

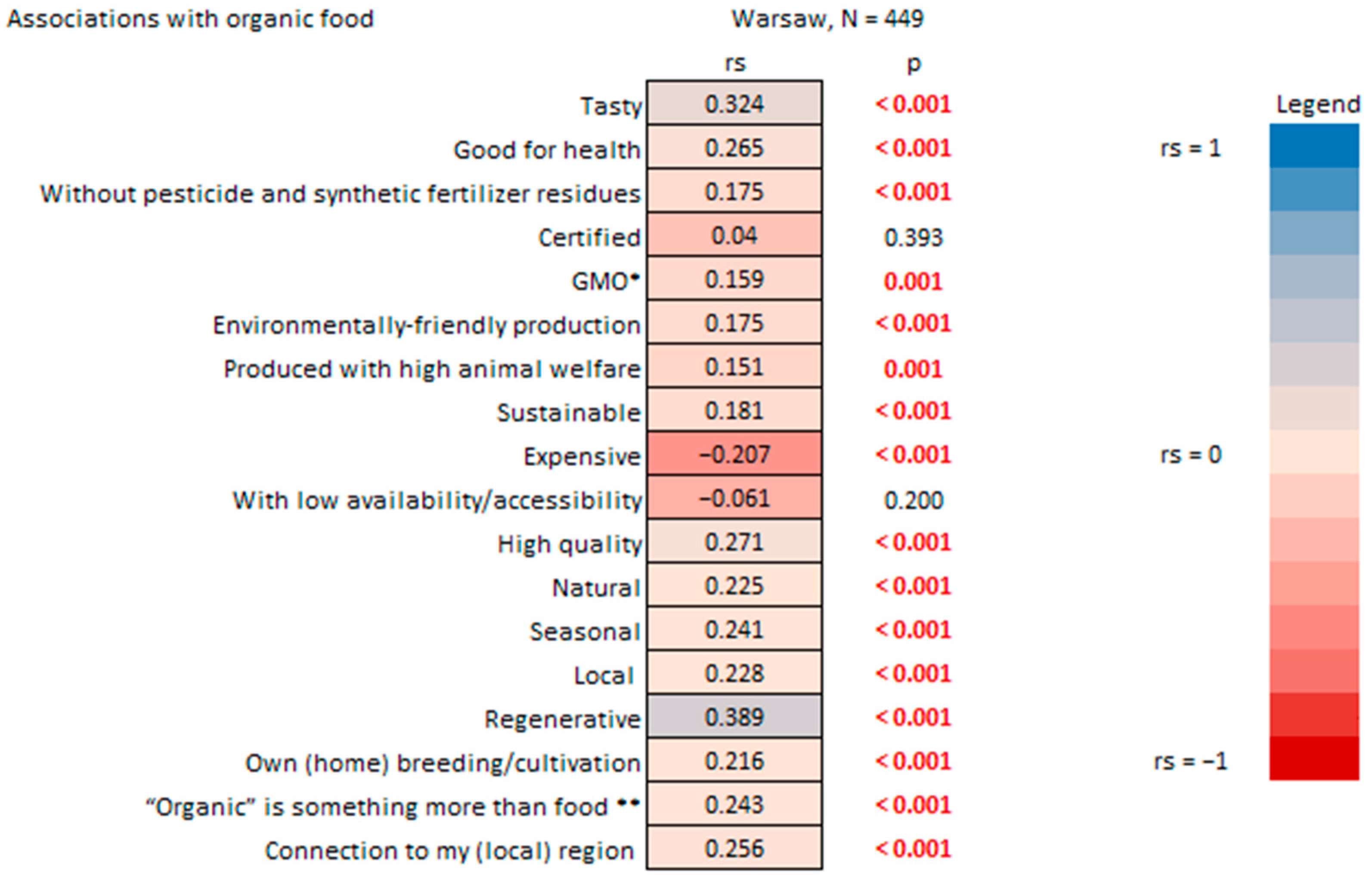

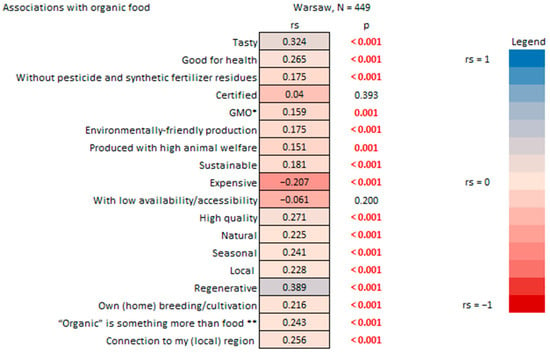

Moreover, a positive correlation was identified between organic consumption and most of the encouraging associations with organic food mentioned in the HHS (Figure 11). The understanding of organic food for organic consumers is associated positively with terms that refer to something more than just a dietary choice. It is associated with “regenerative” aspects, which can be connected to multiple dimensions of sustainability practices [69], but it is also linked to a connotation representing a lifestyle and philosophy that embodies specific values (Figure 11). This indicates that “organic consumers” in Warsaw tend to embrace a more holistic view of the organic food system. This is confirmed by another study that shows that “organic consumers” adhere to more sustainable consumption principles [70] and this “values view” in food systems, according to the research by Varzakas and Antoniadou [24], is important to promote and prioritize sustainability.

Figure 11.

Percentage of organic food consumed by household survey respondents in Warsaw vs. associations with organic food. * Genetically modified organisms; ** it is a lifestyle, philosophy, and it transports values. R-Spearman correlation analysis (p < 0.05).

3.2.3. Willingness to Change Food Habits to More Sustainable Ones

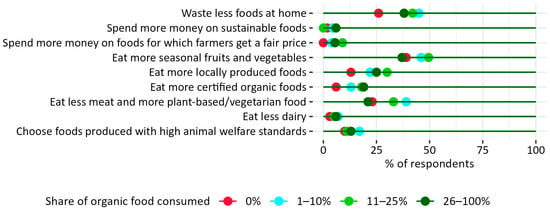

The connection between nascent sustainability awareness and organic consumption may be the reason why 70% of respondents who consume 1–10% of organic food are reporting their willingness to change their eating habits to be more sustainable (Figure 12) and 19% of them are willing to eat more food with an organic certificate (Figure 13). The results showing a statistical trend may signal an increase in the number of organic consumers associated with other sustainable changes in the food system—more than 55% of the members of this group are also willing to eat less meat and more plant-based foods, opt for products with high animal welfare standards, and waste less food (Figure 13).

Figure 12.

Answers to the question: “Are you ready to change your food habits into more sustainable ones” vs. self-reported percentage of organic food in the diet of respondents in Warsaw. Pearson’s chi-squared test results for the overall relationship between variables (Chi2 = 19.85, p = 0.069). N = 449.

Figure 13.

Self-declared percentage of organic food in the respondents’ diet vs. the declared actions that they are ready to undertake to change their food habits into more sustainable ones. N = 254 (respondents who admitted that they are ready to change their diets to more sustainable ones).

4. Conclusions

Although Warsaw is at an early stage of a sustainable urban food system transformation, its citizens are showing readiness to embrace this change. They prefer higher-quality food products and most likely prioritize quality over price in their shopping habits, frequently engaging in alternative food purchasing practices. HHS respondents with higher organic consumption tend to adopt healthier and more sustainable eating habits. Additionally, sustainable and healthy aspects are important to them when selecting food, embracing a values-driven perspective on the food system. This mindset is important for promoting ethical practices, enhancing transparency, restructuring economic frameworks, and striving for a more sustainable and equitable food system. Moreover, there is significant potential for a sustainability transition among the group that currently consumes less organic food (around 1–10%), with a majority indicating a willingness to adjust their eating habits toward more sustainable options. Consequently, it should be a priority for the city engaged in food policy to raise awareness about sustainability and encourage sustainable and organic consumption, adjusting actions to the main actors, for example, encouraging organic farmers to participate in farmers’ markets and promoting the most popular organic products like vegetables, fruits, and eggs. When considering public procurement, the above-mentioned organic products should be included, being the most preferred. Additionally, this research demonstrates that highlighting nutrition and health benefits can effectively enhance the marketing of organic products.

These results are opening up promising opportunities in regions where organic consumption has yet to gain traction. As such, Warsaw serves as a valuable case study for other regions in Central Europe, particularly within the V4 group cities like Budapest and Prague that have similar levels of organic consumption. This is especially relevant in addressing contemporary challenges, such as implementing Green Public Procurement (GPP) in public catering and developing sustainable urban food policies in all of these urban realities.

The approach used in this study has its strengths but also limitations. The primary limitation of this study was the implementation of the “river” sampling methodology—a non-probabilistic approach to participant selection, which limits the generalizability of findings given the non-random nature of the sample. Despite this constraint, the methodology enabled us to engage with a substantial number of participants, thereby facilitating data collection. The primary strength of this study lies in its contribution to filling the existing knowledge gap regarding the links between organic food and other sustainable consumer food-related behaviors in Warsaw, providing valuable data for the development of urban food policy, in line with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the European Green Deal policies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu17132113/s1, Table S1: Household survey—selected questions used for this publication; Table S2: Frequency of choosing organic products by household survey respondents in Warsaw (% of respondents); Table S3: Answers to the household survey question: “How important are the following attributes for your food choices?”.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.G.-W. and D.Ś.-T.; methodology, all authors; software, R.G.-W.; validation, all authors; formal analysis, R.G.-W.; investigation, R.G.-W. and D.Ś.-T.; translation, R.G.-W.; data curation, R.G.-W.; writing—original draft preparation, R.G.-W.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, R.G.-W. and K.K.; supervision, D.Ś.-T.; project administration, L.S. and D.Ś.-T.; funding acquisition, D.Ś.-T., C.S., H.E.B., P.P., and Y.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

These results have been achieved within the SysOrg project “Organic agro-food systems as models for sustainable food systems in Europe and Northern Africa”. The authors acknowledge the financial support for this project provided by transnational funding bodies, partners of the H2020 ERA-NETs SUSFOOD2, and CORE Organic Cofunds under the Joint SUSFOOD2/CORE Organic Call 2019, with national funding from the National Centre for Research and Development—NCBR, Poland (grant number SF-CO/SysOrg/6/2021); the Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture, Federal Organic Farming Scheme (funding reference nos. 2819OE153 and 2819OE154) in Germany; the Italian Ministry of Agriculture, Food Sovereignty, and Forests (grant number no. 9386854, dated 17 December 2020); the Ministry of Higher Education, Scientific Research, and Innovation of Morocco (grant convention no. 4, dated 3 November 2020); and the Green Development and Demonstration Programme (GUDP) under the Danish Ministry of Environment and Food (grant number 34009-20-1694). The publication was (co)financed by the Science Development Fund of the Warsaw University of Life Sciences—SGGW. The funding bodies had no role in the design of this study, its execution, analyses, and interpretation of the data, or decision to submit the results.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee at the Institute of Human Nutrition Sciences of the Warsaw University of Life Sciences (approval number: 50/2021, date: 15 November 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the study participants and the whole SysOrg consortium: Susanne Gjedsted Bügel, Laura Rossi, Friederike Elsner, Beatriz Philippi Rosane, Jacopo Niccolò Di Veroli, and Thea Steenbuch Kraabe Bruun. Their collaborative attitude contributed to the SysOrg project conceptualization and the development of the SysOrg methodological guidelines and thus to the provision of the high-quality results presented in this manuscript. The authors would like to thank Marta Plichta for her contribution to the statistical analysis of the HHS data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CSA | Community-supported agriculture |

| DP | Dietary pattern |

| FAO | The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| FS | Food system |

| GMOs | Genetically modified organisms |

| GPP | Green Public Procurement |

| HHS | Household survey |

| KMO | Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin |

| MUFPP | Urban Food Policy Pact |

| NDGs | National dietary guidelines |

| PHD | Planetary Health Diet |

| SFS | Sustainable food system |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SFC | Sustainable food consumption |

| UN | United Nations |

| V4 | Visegrad Group |

| WHO | The World Health Organization |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Characteristics of the household survey study group.

Table A1.

Characteristics of the household survey study group.

| Variables | N = 449 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 76 | 16.9 |

| Female | 373 | 83.1 |

| Age in years (M ± SD) | 38.6 ± 13.2 | |

| Age in categories | ||

| 18–26 | 97 | 21.6 |

| 27–35 | 95 | 21.2 |

| 36–44 | 119 | 26.5 |

| 45–53 | 72 | 16.0 |

| 54 or more | 66 | 14.7 |

| Level of education | ||

| Secondary or apprenticeship | 91 | 20.3 |

| Bachelor’s degree or equivalent level | 68 | 15.1 |

| Master’s degree or equivalent level | 248 | 55.2 |

| Doctoral studies and/or higher | 42 | 9.4 |

| Disposable net household income per year (PLN) | ||

| I prefer not to answer | 109 | 24.3 |

| Up to 30,000 (lower) | 34 | 7.6 |

| 30,001–45,000 (low) | 31 | 6.9 |

| 45,001–60,000 (medium-low) | 37 | 8.2 |

| 60,001–77,000 (medium) | 33 | 7.4 |

| 77,001–96,000 (medium-high) | 45 | 10.0 |

| 96,001–120,000 (high) | 53 | 11.8 |

| More than 120,000 (highest) | 107 | 23.8 |

References

- Araújo, R.G.; Chavez-Santoscoy, R.A.; Parra-Saldívar, R.; Melchor-Martínez, E.M.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Agro-Food Systems and Environment: Sustaining the Unsustainable. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2023, 31, 100413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The EAT-Lancet Commission on Food, Planet, Health. Available online: https://eatforum.org/content/uploads/2023/12/EAT-Lancet-Global_Consultation_Report_v2.1.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- FAO. Sustainable Food Systems. In Concept and Framework; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- EEA. Perspectives on Transitions to Sustainability. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/perspectives-on-transitions-to-sustainability/file (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- European Commission. A Greener and Fairer CAPA; EC: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- European Commission. Cap Common Agricultural Policy For 2023–2027; EC: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- European Commission. Action Plan for Organic Production in the EU; EC: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- European Commission. Poland’s CAP Strategic Plan; EC: Brussels, Belgium, 2024; Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Strassner, C.; Cavoski, I.; Di Cagno, R.; Kahl, J.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Lairon, D.; Lampkin, N.; Løes, A.K.; Matt, D.; Niggli, U.; et al. How the Organic Food System Supports Sustainable Diets and Translates These into Practice. Front. Nutr. 2015, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willer, H.; Trávnícek, J.; Schlatter, B. The World of Organic Agriculture. In Statistics and Emerging Trends 2025; FiBL, IFOAM—Organics International: Bonn, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kuberska, D.; Grzybowska-Brzezińska, M. Transformation of the Organic Food Market in Poland Using Concentration and Dispersion. Eur. Res. Stud. 2020, 23, 617–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Financial Times European Cities and Regions of the Future 2025. Available online: https://www.fdiintelligence.com/content/c3096814-65ba-51b2-b27a-f17334b43c19 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Soroka, A.; Mazurek-Kusiak, A.K.; Trafialek, J. Organic Food in the Diet of Residents of the Visegrad Group (V4) Countries—Reasons for and Barriers to Its Purchasing. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MUFPP. The Milan Urban Food Policy Pact. Available online: https://www.milanurbanfoodpolicypact.org/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- UM Warszawa. Polityka żywnościowa miasta stołecznego Warszawy. Available online: https://um.warszawa.pl/waw/strategia/polityka-zywnosciowa-przebieg-prac (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Aguirre Sánchez, L.; Roa-Díaz, Z.M.; Gamba, M.; Grisotto, G.; Moreno Londoño, A.M.; Mantilla-Uribe, B.P.; Rincón Méndez, A.Y.; Ballesteros, M.; Kopp-Heim, D.; Minder, B.; et al. What Influences the Sustainable Food Consumption Behaviours of University Students? A Systematic Review. Int. J. Public Health 2021, 66, 1604149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. Sustainable Food Systems Program Proposal. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/ags/docs/SFCP/Activities/2011_FAO-UNEP_Sustainable_Food_Systems_Program__a_proposal_for_the_10YFP.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- OECD. Poland: Country Health Profile 2023, State of Health in the EU. Available online: https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/docs/librariesprovider3/country-health-profiles/chp2023pdf/chp-poland.pdf?sfvrsn=5678c8b_5&download=true (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Komisja Zarządzająca Funduszu Promocji Owoców i Warzyw. Resolution on the Adoption of a Promotion Strategy for the Fruit Industry and Vegetables for 2024; Resolution No. 7/2023 from 14 June 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/attachment/42e70ec6-1f3f-4a18-97c4-6401a3b1aa3f (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Statistics Poland. Domestic Deliveries and Consumption of Selected Consumer Goods per Capita in 2022. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/prices-trade/trade/domestic-deliveries-and-consumption-of-selected-consumer-goods-per-capita-in-2022,9,13.html (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Statistics Poland. Household Budget Survey in 2022. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/living-conditions/living-conditions/household-budget-survey-in-2022,2,18.html (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Varzakas, T.; Antoniadou, M. A Holistic Approach for Ethics and Sustainability in the Food Chain: The Gateway to Oral and Systemic Health. Foods 2024, 13, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Džupka, P.; Kubák, M.; Nemec, P. Sustainable Public Procurement in Central European Countries. Can It Also Bring Savings? Sustainability 2020, 12, 9241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Yao, W.; Yu, T.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, J.; Lin, F.; Zhu, H.; Gunina, A.; Yang, Y.; et al. Long-Term Organic Farming Improves the Red Soil Quality and Microbial Diversity in Subtropics. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 381, 109410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, J.; Brinkmann, J.; Chmelikova, L.; Ebertseder, F.; Freibauer, A.; Gottwald, F.; Haub, A.; Hauschild, M.; Hoppe, J.; Hülsbergen, K.J.; et al. Benefits of Organic Agriculture for Environment and Animal Welfare in Temperate Climates. Org. Agric. 2025, 13, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocean, C.G. The Role of Organic Farming in Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Agriculture in the European Union. Agronomy 2025, 15, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Góralska-Walczak, R.; Stefanovic, L.; Kopczyńska, K.; Kazimierczak, R.; Bügel, S.G.; Strassner, C.; Peronti, B.; Lafram, A.; El Bilali, H.; Średnicka-Tober, D. Entry Points, Barriers, and Drivers of Transformation Toward Sustainable Organic Food Systems in Five Case Territories in Europe and North Africa. Nutrients 2025, 17, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Herpen, E.; van Geffen, L.; Nijenhuis-de Vries, M.; Holthuysen, N.; van der Lans, I.; Quested, T. A Validated Survey to Measure Household Food Waste. MethodsX 2019, 6, 2767–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Herpen, H.W.I.; van der Lans, I.A.; Nijenhuis, M.A.; Holthuysen, N.T.E.; Kremer, S.; Stijnen, D.A.J.M.; van Geffen, E.J. Consumption Life Cycle Contributions: Assessment of Practical Methodologies for in Home Food Waste Measurement. Refresh. 2016. Available online: https://eu-refresh.org/sites/default/files/D1.3%20final%20report%20Nov%202016.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- BEUC. One Bite at a Time: Consumers and the Transition to Sustainable Food. Analysis of a Survey of European Consumers on Attitudes Towards Sustainable Food; The European Consumer Organisation: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lehdonvirta, V.; Oksanen, A.; Räsänen, P.; Blank, G. Social Media, Web, and Panel Surveys: Using Non-Probability Samples in Social and Policy Research. Policy Internet 2021, 13, 134–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Available online: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Smoluk-Sikorska, J.; Śmiglak-Krajewska, M.; Rojík, S.; Fulnečková, P.R. Prices of Organic Food—The Gap between Willingness to Pay and Price Premiums in the Organic Food Market in Poland. Agriculture 2024, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farma Świętokrzyska. Trendy w Ekozakupach Polaków. Available online: https://farmaswietokrzyska.pl/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Trendy-w-ekozakupach.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Śmiglak-Krajewska, M.; Wojciechowska-Solis, J. Consumption Preferences of Pulses in the Diet of Polish People: Motives and Barriers to Replace Animal Protein with Vegetable Protein. Nutrients 2021, 13, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajdakowska, M.; Gębski, J.; Jeżewska-Zychowicz, M.; Gutkowska, K.; Kosicka-Gębska, M. Polish Consumers’ Perception of Plant-Based Alternatives. Technol. Prog. Food Process 2023, 33, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, D.; Jaworska, D.; Affeltowicz, D.; Maison, D. Plant-Based Dairy Alternatives: Consumers’ Perceptions, Motivations, and Barriers—Results from a Qualitative Study in Poland, Germany, and France. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuba-Ciszewska, M.; Kowalska, A.; Brodziak, A.; Manning, L. Organic Milk Production Sector in Poland: Driving the Potential to Meet Future Market, Societal and Environmental Challenges. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, A.; Ratajczyk, M.; Manning, L.; Bieniek, M.; Mącik, R. “Young and Green” a Study of Consumers’ Perceptions and Reported Purchasing Behaviour towards Organic Food in Poland and the United Kingdom. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassen, A.D.; Lehmann, C.; Andersen, E.W.; Werther, M.N.; Thorsen, A.V.; Trolle, E.; Gross, G.; Tetens, I. Gender Differences in Purchase Intentions and Reasons for Meal Selection among Fast Food Customers—Opportunities for Healthier and More Sustainable Fast Food. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 47, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO and WHO. Sustainable Healthy Diets: Guiding Principles; Rome, 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241516648 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Narodowy Instytut Zdrowia Publicznego PZH—Państwowy Instytut Badawczy. Healthy Eating Plate. Available online: https://ncez.pzh.gov.pl/abc-zywienia/talerz-zdrowego-zywienia/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Rychlik, E.; Stoś, K.; Woźniak, A.; Mojskiej, H. Normy Żywienia Dla Populacji Polski; Narodowy Instytut Zdrowia Publicznego PZH-Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warsaw, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Loken, B.; Opperman, J.; Orr, S.; Fleckenstein, M.; Halevy, S.; McFeely, P.; Park, S.; Weber, C. Bending the Curve: The Restorative Power of Planet-Based Diets; WWF: Gland, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, M.M.; Gamage, E.; Du, S.; Ashtree, D.N.; McGuinness, A.J.; Gauci, S.; Baker, P.; Lawrence, M.; Rebholz, C.M.; Srour, B.; et al. Ultra-Processed Food Exposure and Adverse Health Outcomes: Umbrella Review of Epidemiological Meta-Analyses. BMJ 2024, 384, e077310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woś, K.; Dobrowolski, H.; Gajewska, D.; Rembiałkowska, E. Diet Quality Indicators and Organic Food Consumption in Mothers of Young Children. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 2025, 7, 3900–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rempelos, L.; Wang, J.; Barański, M.; Watson, A.; Volakakis, N.; Hoppe, H.W.; Kühn-Velten, W.N.; Hadall, C.; Hasanaliyeva, G.; Chatzidimitriou, E.; et al. Diet and Food Type Affect Urinary Pesticide Residue Excretion Profiles in Healthy Individuals: Results of a Randomized Controlled Dietary Intervention Trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 50. Barilla Center for Food & Nutrition Foundation. Diets That Respect the Health of People and the Planet. Available online: https://fondazionebarilla.com/uploads/2021/05/Diets_that_respect_the_health_of_people_and_the_Planet.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Seconda, L.; Baudry, J.; Allès, B.; Hamza, O.; Boizot-Szantai, C.; Soler, L.G.; Galan, P.; Hercberg, S.; Lairon, D.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Assessment of the Sustainability of the Mediterranean Diet Combined with Organic Food Consumption: An Individual Behaviour Approach. Nutrients 2017, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando Ruini, L.; Ciati, R.; Alberto Pratesi, C.; Marino, M.; Principato, L.; Vannuzzi, E.; Serafini, M.; Ge Fratelli SpA, B.R. Working toward Healthy and Sustainable Diets: The “Double Pyramid Model” Developed by the Barilla Center for Food and Nutrition to Raise Awareness about the Environmental and Nutritional Impact of Foods Introduction. Front. Nutr. 2015, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Góralska-Walczak, R.; Kopczyńska, K.; Kazimierczak, R.; Stefanovic, L.; Bieńko, M.; Oczkowski, M.; Średnicka-Tober, D. Environmental Indicators of Vegan and Vegetarian Diets: A Pilot Study in a Group of Young Adult Female Consumers in Poland. Sustainability 2024, 16, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso González, P.; Extremo Martín, C.; Otero Enríquez, R.; de la Cruz Modino, R.; Arocha Alonso, F.N.; Rodríguez, S.G.; Parga Dans, E. Insights into Organic Food Consumption in Tenerife (Spain): Examining Consumer Profiles and Preferences. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesse-Guyot, E.; Lairon, D.; Allès, B.; Seconda, L.; Rebouillat, P.; Brunin, J.; Vidal, R.; Taupier-Letage, B.; Galan, P.; Amiot, M.J.; et al. Key Findings of the French BioNutriNet Project on Organic Food-Based Diets: Description, Determinants, and Relationships to Health and the Environment. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 208–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.L.M.; Frederiksen, K.; Raaschou-Nielsen, O.; Hansen, J.; Kyro, C.; Tjonneland, A.; Olsen, A. Organic Food Consumption Is Associated with a Healthy Lifestyle, Socio-Demographics and Dietary Habits: A Cross-Sectional Study Based on the Danish Diet, Cancer and Health Cohort. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 1543–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettmann, R.L.; Dimitri, C. Who’s Buying Organic Vegetables? Demographic Characteristics of U.S. Consumers. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2009, 16, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditlevsen, K.; Sandøe, P.; Lassen, J. Healthy Food Is Nutritious, but Organic Food Is Healthy Because It Is Pure: The Negotiation of Healthy Food Choices by Danish Consumers of Organic Food. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 71, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- fDi Intelligence. European Cities and Regions of the Future 2024. Available online: https://www.fdiintelligence.com/content/7de38f51-976d-5086-afd2-e45023c9de16 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Statistic Poland. Report on the Socio-Economic Situation of Mazowieckie Voivodship 2023. Available online: https://warszawa.stat.gov.pl/en/publications/others/report-on-the-socio-economic-situation-of-mazowieckie-voivodship-2023,5,9.html (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- MyBestPharm. Nawyki Zdrowotne i Żywieniowe Polaków w Czasach Wielkiej Inflacji. Available online: https://mybestpharm.com/nawyki-zdrowotne-i-zywieniowe-polakow-w-czasach-inflacji/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Rejman, K.; Kaczorowska, J.; Halicka, E.; Prandota, A. How Do Consumers Living in European Capital Cities Perceive Foods with Sustainability Certificates? Foods 2023, 12, 4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UM Warszawa. Report on the Study of Shopping and Eating Habits of Warsaw Residents in the Context of Food Waste. Available online: https://en.um.warszawa.pl/-/we-eat-not-waste (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Renting, H.; Marsden, T.K.; Banks, J. Understanding Alternative Food Networks: Exploring the Role of Short Food Supply Chains in Rural Development. Environment and Planning A. Econ. Space 2003, 35, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piorr, A.; Zasada, I.; Doernberg, A.; Zoll, F.; Ramme, W. Research for AGRI Committee—Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture in the EU. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/617468/IPOL_STU(2018)617468_EN.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Noack, F.; Engist, D.; Gantois, J.; Gaur, V.; Hyjazie, B.F.; Larsen, A.; M’Gonigle, L.K.; Missirian, A.; Qaim, M.; Sargent, R.D.; et al. Environmental Impacts of Genetically Modified Crops. Science 2024, 385, e2501605122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chukwurah, G.O.; Okeke, F.O.; Isimah, M.O.; Enoguanbhor, E.C.; Awe, F.C.; Nnaemeka-Okeke, R.C.; Guo, S.; Nwafor, I.V.; Okeke, C.A. Cultural Influence of Local Food Heritage on Sustainable Development. World 2025, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowska-Solis, J.; Barska, A. Exploring the Preferences of Consumers’ Organic Products in Aspects of Sustainable Consumption: The Case of the Polish Consumer. Agriculture 2021, 11, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.; Farny, S.; Abson, D.J.; Zuin Zeidler, V.; von Salisch, M.; Schaltegger, S.; Martín-López, B.; Temperton, V.M.; Kümmerer, K. Mainstreaming Regenerative Dynamics for Sustainability. Nat. Sustain. 2024, 7, 964–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalvedi, M.L.; Saba, A. Exploring Local and Organic Food Consumption in a Holistic Sustainability View. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).