Health Claims for Protein Food Supplements for Athletes—The Analysis Is in Accordance with the EFSA’s Scientific Opinion

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Sports Food Supplements

1.2. Sports Food Supplements, Scientific Evidence and Legislation

1.3. Protein Supplements

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Type of Study

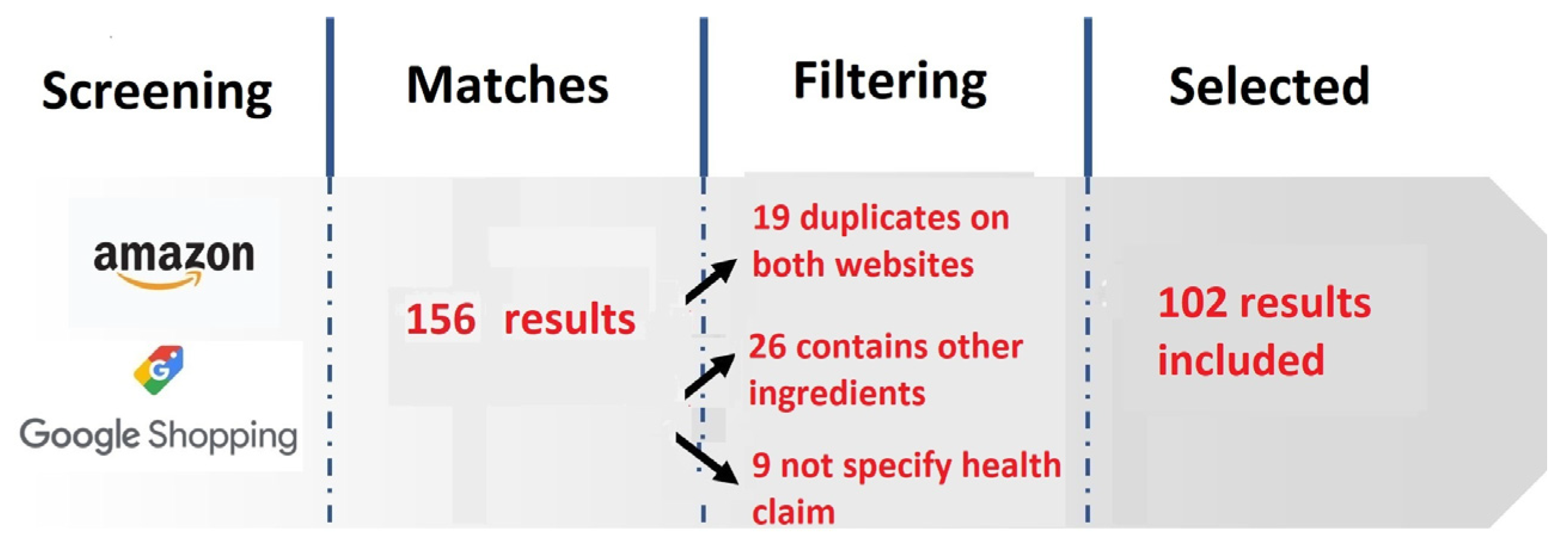

2.2. Study Population Selection Strategy

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Extraction

- Product name: name of each of the supplements belonging to the study sample;

- Sportsbramd: brand name of each supplement in the sample. The SFSs in the sample were defined (Appendix A);

- Health claims for protein supplements: those present on the product’s technical data sheet or company website of each of the supplements in the requested sample;

- Dosage: amount of product consumed, as recommended by the manufacturer in each supplement;

- Nutritional information: value of nutrients, carbohydrates, proteins, fats and salt in each of the supplements in the sample.

2.5. Data Analysis

- Approved health claims: EFSA-approved health claims for proteins;

- Total supplements in which this statement is made (no. and %): total number and percentage of supplements in the sample in which this statement is made;

- Comply with the conditions of use: conditions based on Regulation (EC) No. 432/2012 [28];

- Number and percentage of supplements in which these conditions of use are met for this claim: number and percentage of supplements in the sample in which the conditions of use are met for each claim;

- Unauthorized health claims. Relation to health: health claims not authorized by the EFSA for whey and casein proteins;

- Health claims stated on the product or on the company’s website: health claims stated on each of the supplements in the sample;

- Number and percentage of supplements in the sample where the claim appears, either on the product or the company’s website Adequacy yes/no: whether the health claims of each of the supplements in the sample conform to the health claims defined by the EFSA;

- Reason: according to the EFSA’s scientific opinion, the reason for compliance or non-compliance and the proposed modification of the supplements in the sample to achieve a better adaptation to the approved health claims. Number 1 to 5, from non-compliant to compliant, respectively. Number 1. Reason: not in accordance with the approved protein claims and the recommended appropriate dosage of the product. Proposed modification: delete product claim. Number 2: Reason: Conforms to the recommended appropriate dosage of the product, but the text of the statement indicated does not conform to the approved one. Proposed modification: modify the declaration by specifying the exact text of the approved declaration Number 3. Reason: Conforms to the appropriate recommended dosage of the product, but the text of the approved statement is missing. Modification proposal: modify the statement by specifying the exact text of the approved statement. Number 4. Reason: Conforms to the appropriate recommended dosage of the product, but some words in the text of the declaration need to be changed. Proposal for amendment: amend the declaration by specifying the exact text of the approved declaration. Number 5. Reason: Conforms to all of the above. Proposed modification: do not modify or delete the declaration.

2.6. Compliance with Legislation and Scientific Evidence

3. Results

3.1. Indicated Conditions of Use of the Product

3.2. Health Claims Not Authorized by the EFSA

3.3. Health Claims, and Compliance with Current European Legislation and Scientific Evidence

3.4. Degree of Compliance and Proposals for Modifications

4. Discussion

4.1. Health Claims and Proposed Dosages

4.2. Fraud in Advertising and Direct Consumer Information

4.3. Action to Be Taken in the Face of Advertising Fraud

4.4. Cases of Advertising Fraud

4.5. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AESAN | Agency for Food Safety and Nutrition |

| AIS | Australian Institute of Sport |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| AUC | Association of Communication Users |

| Autocontrol | Association for the Self-Regulation of Commercial Communication |

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| IOC | International Olympic Committee |

| ISSN | International Society of Sports Nutrition |

| SFS | Sports food supplements |

| WADA | World Anti-Doping Agency |

Appendix A

| Health Claims Stated on the Product or Company Website | Supplement Company |

|---|---|

| Protein contributes to muscle mass increase |

|

| Proteins contribute to the growth and development of muscle mass. |

|

| Protein source that helps to increase muscle mass |

|

| Contributes to growth, increase, development, gain of muscle mass |

|

| Protein (100% casein, whey protein, protein content) contributes to the growth, increase of muscle mass. |

|

| (favors, aids, supports, promotes, fosters, perfect for) muscle growth |

|

| Promotes muscle building |

|

| (Helps, favors) muscle gain, muscle mass |

|

| (Helps, favors, promotes) muscle development, muscle mass |

|

| Objective to gain, develop muscle mass |

|

| Designed to help you build muscle |

|

| To increase muscle mass |

|

| Can improve the development of muscle growth |

|

| To accelerate muscle building |

|

| Protein helps to maintain muscle mass |

|

| Protein contributes to the maintenance of muscle mass |

|

| They contribute to the maintenance, maintenance of muscle mass, muscle |

|

| To help maintain, regenerate muscle, muscle mass |

|

| Proteins are important for the maintenance of our muscles. |

|

| Muscle maintenance |

|

| Sustained supply of amino acids to prevent loss of muscle mass |

|

| Protein (100% Whey Isolate, 100% casein, whey protein) contributes to the maintenance of muscle mass. |

|

| Prevents muscle mass/tone loss |

|

| Promotes muscle retention |

|

| To feed your muscles |

|

| For nocturnal muscle support |

|

| Muscle definition |

|

| Proteins contribute to the maintenance of normal bones. |

|

| Source of protein that contributes to the maintenance of bones in a proper state. |

|

| 100% casein protein contributes to the maintenance of normal bones. |

|

| 100% Whey Isolate protein contributes to the maintenance of normal bone structure. |

|

| Protein content contributes to the maintenance of proper bone health |

|

| Contributes to the maintenance of bones in normal conditions. |

|

| Whey protein helps to maintain a normal bone system. |

|

| Maintenance of healthy bones |

|

| Development of your bone health |

|

| Can help you maintain healthy bones |

|

| Promotes bones |

|

References

- EFSA. Agencia Europea de Seguridad Alimentaria; ESFA: Parma, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Maughan, R.J.; Burke, L.M.; Dvorak, J.; Larson-Meyer, D.E.; Peeling, P.; Phillips, S.M.; Rawson, E.S.; Walsh, N.P.; Garthe, I.; Geyer, H.; et al. IOC Consensus Statement: Dietary Supplements and the High-Performance Athlete. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltazar-Martins, G.; Brito De Souza, D.; Aguilar-Navarro, M.; Muñoz-Guerra, J.; Plata, M.D.M.; Del Coso, J. Prevalence and Patterns of Dietary Supplement Use in Elite Spanish Athletes. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2019, 16, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garthe, I.; Maughan, R.J. Athletes and Supplements: Prevalence and Perspectives. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2018, 28, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maughan, R.J.; Greenhaff, P.L.; Hespel, P. Dietary Supplements for Athletes: Emerging Trends and Recurring Themes. J. Sports Sci. 2011, 29, S57–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maughan, R. Contamination of Dietary Supplements and Positive Drug Tests in Sport. J. Sports Sci. 2005, 23, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawardena, R.; Weerasinghe, K.; Trakman, G.; Madhujith, T.; Hills, A.P.; Kalupahana, N.S. Sports Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaires Developed for the Athletic Population: A Systematic Review. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2023, 12, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, V.N.; Andrade, M.S.; Sinisgalli, R.; Vancini, R.L.; de Conti Teixeira Costa, G.; Weiss, K.; Knechtle, B.; de Lira, C.A.B. Prevalence of dietary supplement use among male Brazilian recreational triathletes: A cross-sectional study. BMC Res. Notes 2024, 17, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broniecka, A.; Sarachman, A.; Zagrodna, A.; Książek, A. Dietary supplement use and knowledge among athletes: Prevalence, compliance with AIS classification, and awareness of certification programs. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2025, 22, 2496450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-López, J.; Pérez, A.B.; Gamarra-Morales, Y.; Vázquez-Lorente, H.; Herrera-Quintana, L.; Sánchez-Oliver, A.J.; Planells, E. Prevalence of sports supplements consumption and its association with food choices among female elite football players. Nutrition 2024, 118, 112239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-García, D.; Martínez-Sanz, J.M.; Sebastiá-Rico, J.; Manchado, C.; Vaquero-Cristóbal, R. Pattern of Consumption of Sports Supplements of Spanish Handball Players: Differences According to Gender and Competitive Level. Nutrients 2024, 16, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastiá-Rico, J.; Martínez-Sanz, J.M.; Sanchis-Chordà, J.; Alonso-Calvar, M.; López-Mateu, P.; Romero-García, D.; Soriano, J.M. Supplement Consumption by Elite Soccer Players: Differences by Competitive Level, Playing Position, and Sex. Healthcare 2024, 12, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez, R.; López-León, I.; Moreno-Lara, J.; Rico, E.; Sánchez-Oliver, A.J.; Sánchez-Gómez, Á.; Pecci, J. Sport supplementation in competitive swimmers: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2025, 22, 2486988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Institute of Sports (AIS). Australian Sport Commission. Supplements. Available online: https://www.ais.gov.au/nutrition/supplements/group_a#isolated_protein_supplementA (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Martínez-Sanz, J.; Sospedra, I.; Baladía, E.; Arranz, L.; Ortiz-Moncada, R.; Gil-Izquierdo, A. Current Status of Legislation on Dietary Products for Sportspeople in a European Framework. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ley 33/2011, de 4 de Octubre, General de Salud Pública; Ministerio de la Presidencia, Justicia y Relaciones con las Cortes: Madrid, Spain, 2011; pp. 104593–104626.

- Juhn, M.S. Popular Sports Supplements and Ergogenic Aids. Sports Med. 2003, 33, 921–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, A.S.; Ponomareva, M.N.; Sukhanov, B.P. Regulation of food supplements in the European Union and its member states. Part I. Vopr. Pitan. 2014, 83, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA. Scientific Opinion on the Substantiation of Health Claims Related to Protein and Increase in Satiety Leading to a Reduction in Energy Intake (ID 414, 616, 730), Contribution to the Maintenance or Achievement of a Normal Body Weight (ID 414, 616, 730), Maintenance of Normal Bone (ID 416) and Growth or Maintenance of Muscle Mass (ID 415, 417, 593, 594, 595, 715) Pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, R.W.; Murphy, K.T.; McKellar, S.R.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Henselmans, M.; Helms, E.; Aragon, A.A.; Devries, M.C.; Banfield, L.; Krieger, J.W.; et al. A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression of the Effect of Protein Supplementation on Resistance Training-Induced Gains in Muscle Mass and Strength in Healthy Adults. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrosa, M.; Gil-Izquierdo, A.; González-Rodríguez, L.G.; Alférez, M.J.M.; San Juan, A.F.; Sánchez-Gómez, Á.; Calvo-Ayuso, N.; Ramos-Álvarez, J.J.; Fernández-Lázaro, D.; Lopez-Grueso, R.; et al. Nutritional Strategies for Optimizing Health, Sports Performance, and Recovery for Female Athletes and Other Physically Active Women: A Systematic Review. Nutr. Rev. 2025, 83, e1068–e1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.; Wang, E. Demand for “Healthy” Products: False Claims and FTC Regulation. J. Mark. Res. 2017, 54, 968–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, D.; Schwartz, J. Stopping Deceptive Health Claims: The Need for a Private Right of Action Under Federal Law. Am. J. Law Med. 2016, 42, 53–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Sanz, J.M.; Sala Ripoll, M.; Puya Braza, J.M.; Martínez Segura, A.; Sánchez Oliver, A.J.; Mata, F.; Cortell Tormo, J.M. Fraud in Nutritional Supplements for Athletes: A Narrative Review. Nutr. Hosp. 2021, 38, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Hernández, M.D.; Gil-Izquierdo, Á.; García, C.J.; Gabaldón, J.A.; Ferreres, F.; Giménez-Monzó, D.; Martínez-Sanz, J.M. Health Claims for Sports Drinks—Analytical Assessment According to European Food Safety Authority’s Scientific Opinion. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichner, A.; Tygart, T. Adulterated dietary supplements threaten the health and sporting career of up-and-coming young athletes. Drug Test. Anal. 2016, 8, 304–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and Elaboration. Epidemiology 2007, 18, 805–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reglamento (UE) No 432/2012 de La Comisión, de 16 de Mayo de 2012, Por El Que Se Establece Una Lista de Declaraciones Autorizadas de Propiedades Saludables de Los Alimentos Distintas de Las Relativas a La Reducción Del Riesgo de Enfermedad y al Desarrollo y La Salud de Los niñosTexto Pertinente a Efectos Del EEE. 2012. Available online: https://www.boe.es/doue/2012/136/L00001-00040.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Reglamento No 1924/2006 Del Parlamento Europeo y Del Consejo de 20 de Diciembre de 2006 Relativo a Las Declaraciones Nutricionales y de Propiedades Saludables En Los Alimentos. 2006. Available online: https://www.boe.es/doue/2006/404/L00009-00025.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Pasiakos, S.M.; Lieberman, H.R.; McLellan, T.M. Effects of Protein Supplements on Muscle Damage, Soreness and Recovery of Muscle Function and Physical Performance: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2014, 44, 655–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriels, G.; Lambert, M. Nutritional Supplement Products: Does the Label Information Influence Purchasing Decisions for the Physically Active? Nutr. J. 2013, 12, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Lopez, P.; Rueda-Robles, A.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, L.; Blanca-Herrera, R.M.; Quirantes-Piné, R.M.; Borrás-Linares, I.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Lozano-Sánchez, J. Analysis and Screening of Commercialized Protein Supplements for Sports Practice. Foods 2022, 11, 3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Register of Nutrition and Health Claims; European Commission: Brussel, Belgium, 2014; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/food-feed-portal/screen/health-claims/eu-register (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- AESAN Agencia Española de Seguridad Alimentaria 2003. Available online: https://www.aesan.gob.es/AECOSAN/web/home/aecosan_inicio.htm (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Estevan Navarro, P.; Sospedra, I.; Perales, A.; González-Díaz, C.; Jiménez-Alfageme, R.; Medina, S.; Gil-Izquierdo, A.; Martínez-Sanz, J.M. Caffeine Health Claims on Sports Supplement Labeling. Analytical Assessment According to EFSA Scientific Opinion and International Evidence and Criteria. Molecules 2021, 26, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina Juan, L.; Sospedra, I.; Perales, A.; González-Díaz, C.; Gil-Izquierdo, A.; Martínez-Sanz, J.M. Analysis of Health Claims Regarding Creatine Monohydrate Present in Commercial Communications for a Sample of European Sports Foods Supplements. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 632–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, N.; Beas, S.; Gras, N.; Ronco, A.M. Fraude Alimentario: Pasado, Presente y Futuro. Rev. Chil. Nutrición 2023, 50, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asociación de Usuarios de La Comunicación (AUC) 2013. Available online: https://www.auc.es/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Asociacion Para La Autorregulación de La Comunicación Comercial (Autocontrol) 1995. Available online: https://www.autocontrol.es/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Cole, M.R.; Fetrow, C.W. Adulteration of Dietary Supplements. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2003, 60, 1576–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| EFSA | Terms and Conditions of Use | Statement to Be Indicated |

|---|---|---|

| Regulation (EC) No. 432/2012 [28] Regulation (EC) No. 1924/2006 [29] | a. Foods that are at least a source of protein: provide at least 12% of the food’s energy value. | Protein contributes to muscle mass increase |

| Regulation (EC) No. 432/2012 [28] Regulation (EC) No. 1924/2006 [29] | b. Foods that are at least a source of protein: they provide at least 12% of the energy value of the food. | Protein helps to maintain muscle mass |

| Regulation (EC) No. 432/2012 [28] Regulation (EC) No. 1924/2006 [29] | c. Foods that are at least a source of protein: they provide at least 12% of the energy value of the food. | Proteins contribute to the maintenance of normal bones. |

| Regulation (EC) No. 1924/2006 [29] | d. If the proteins provide at least 20% of the energy value of the food. | High protein content 1 |

| Approved Health Claim | Total Supplements in Which This Statement Is Given | Comply Terms and Conditions of Use * | No. and % Supplements in Which This Dosage Is Given for This Statement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO. | (%) | ||||

| Protein contributes to muscle mass increase | 99 | 97.1% | Complies a. | 99 | 1100% |

| Protein helps to maintain muscle mass | 79 | 77.5% | Complies b. | 79 | 100% |

| Proteins contribute to the maintenance of normal bones. | 31 | 30.4% | Complies c. | 31 | 100% |

| Unauthorized Health Claims * Relationship to Health | Health Claims of the Product or Company Website | No. of Supplements Where the Statement Appears | % Supplements Where the Statement Appears |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whey protein: Faster recovery from muscle fatigue after exercise | Promotes muscle recovery | 5 | 7.9% |

| Post-workout recovery | 7 | 11.1% | |

| Improve recovery | 4 | 6.3% | |

| Whey protein: increased endurance capacity during the next bout of exercise after strenuous exercise. | Supports muscle growth for even better performance | 4 | 6.3% |

| Objective: Resistance | 1 | 1.6% | |

| Improved sports performance | 4 | 6.3% | |

| Improved performance and fast recovery from workouts | 1 | 1.6% | |

| Whey protein: skeletal muscle tissue repair | Whey protein benefits muscle fiber recovery | 2 | 3.2% |

| Recommended for those looking to recover their muscle tissues after training. | 2 | 3.2% | |

| Tissue recovery | 2 | 3.2% | |

| Key amino acids for proper muscle function and recovery | 1 | 1.6% | |

| Whey protein: growth or maintenance of muscle mass | Whey protein benefits muscle growth | 1 | 1.6% |

| Whey protein target muscle development muscle maintenance and recovery | 1 | 1.6% | |

| Whey protein with amino acids helps increase muscle mass and supports muscle tissue maintenance. | 1 | 1.6% | |

| Whey protein for muscle volume increase | 2 | 3.2% | |

| Whey protein: increase in muscle strength | Improves strength | 1 | 1.6% |

| Increased strength | 2 | 3.2% | |

| Whey protein: reduction of body fat mass during energy restriction and resistance training. | Supports fat loss | 1 | 1.6% |

| Whey protein: increased satiety leading to reduced energy intake | Helps to reduce appetite, soothe the desire to eat | 1 | 1.6% |

| Whey protein: growth or maintenance of muscle mass | Stimulate protein synthesis, the process that causes muscles to grow because the amino acids it contains are transported to the muscles through the bloodstream | 1 | 1.6% |

| Your protein synthesis is accelerated and your body is able to build muscle. | 2 | 3.2% | |

| Whey protein: increased satiety leading to reduced energy intake | Satiety control | 1 | 1.6% |

| Weight loss | 1 | 1.6% | |

| Helps reduce appetite | 2 | 3.2% | |

| Whey protein: faster recovery from post-exercise muscle fatigue | A premium quality whey protein isolate formulated to feed your muscles fast, so you can recover faster. | 1 | 1.6% |

| Casein: Growth or maintenance of muscle mass | Perfect micellar casein to prevent catabolization | 3 | 4.8% |

| Prevents muscle catabolism | 1 | 1.6% | |

| Promotes muscle recovery | 6 | 9.5% | |

| Promotes recovery of damaged fibers against catabolism. | 1 | 1.6% | |

| Hydrolyzed Casein: faster recovery from muscle fatigue after exercise | Supplies the amino acids your body needs to recover while you sleep | 1 | 1.6% |

| Approved Health Claim | Health Claims of the Product or Company Website | No. of Supplements Where the Statement Appears | % Supplements Where the Statement Appears | Degree of Adequacy * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein contributes to muscle mass increase | Protein contributes to muscle mass increase | 7 | 3.3% | Yes |

| Protein contributes to the growth and development of muscle mass. | 16 | 7.7% | Yes | |

| Protein source that helps to increase muscle mass | 2 | 1.0% | No | |

| Contributes (to the growth, increase, development, gain) of muscle mass | 15 | 7.2% | No | |

| Protein (100% casein, whey protein, protein content) contributes to the growth, increase of muscle mass. | 9 | 4.3% | No | |

| (favors, assists, supports, promotes, encourages, perfect for) muscle growth | 13 | 6.2% | No | |

| Promotes muscle building | 1 | 0.5% | No | |

| (Helps, favors) muscle gain, muscle mass | 4 | 1.9% | No | |

| (Helps, favors, promotes) muscle development, muscle mass | 21 | 10.0% | No | |

| Objective to gain, develop muscle mass | 2 | 1.0% | No | |

| Designed to help you build muscle | 1 | 0.5% | No | |

| To increase muscle mass | 5 | 2.4% | No | |

| Can improve the development of muscle growth | 2 | 1.0% | No | |

| To accelerate muscle building | 1 | 0.5% | No | |

| Proteins help to preserve muscle mass | Protein helps to maintain muscle mass | 6 | 2.9% | Yes |

| Protein contributes to the maintenance of muscle mass | 18 | 8.6% | Yes | |

| Contribute to the maintenance, maintenance of muscle mass, muscle | 6 | 2.9% | No | |

| To help maintain, regenerate muscle, muscle mass | 21 | 10.0% | No | |

| Proteins are important for the maintenance of our muscles. | 1 | 0.5% | No | |

| Muscle maintenance | 8 | 3.8% | No | |

| Sustained supply of amino acids to prevent loss of muscle mass | 1 | 0.5% | No | |

| Protein (100% Whey Isolate, 100% casein, whey protein) contributes to the maintenance of muscle mass. | 10 | 4.8% | No | |

| Prevents muscle mass/tone loss | 1 | 0.5% | No | |

| Promotes muscle retention | 1 | 0.5% | No | |

| To feed your muscles | 1 | 0.5% | No | |

| For nocturnal muscle support | 4 | 1.9% | No | |

| Muscle definition | 1 | 0.5% | No | |

| Proteins contribute to the maintenance of normal bones. | Proteins contribute to the maintenance of normal bones. | 11 | 5.3% | Yes |

| Source of protein that contributes to the maintenance of bones in a proper state. | 2 | 1.0% | Yes | |

| 100% casein protein contributes to the maintenance of normal bones. | 1 | 0.5% | No | |

| 100% Whey Isolate protein contributes to the maintenance of normal bone structure. | 2 | 1.0% | No | |

| Protein content contributes to the maintenance of proper bone health | 1 | 0.5% | No | |

| Contributes to the maintenance of bones in normal conditions. | 2 | 1.0% | No | |

| Whey protein helps to maintain a normal bone system. | 7 | 3.3% | No | |

| Maintenance of healthy bones | 1 | 0.5% | No | |

| Development of your bone health | 2 | 1.0% | No | |

| Can help you maintain healthy bones | 1 | 0.5% | No | |

| Promotes bones | 1 | 0.5% | No |

| Approved Nutritional Statements | Nutrition Claims Stated on the Product or Company Website | No. of Supplements Where the Statement Appears | % Supplements Where the Statement Appears | Degree of Adequacy 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High protein content | High protein content | 2 | 66.6% | Yes |

| Contains high protein | 1 | 33.3% | Yes |

| Messages Indicated in the Product or Company Website | No. of Supplements Where the Message Appears | % Supplements Where the Message Appears |

|---|---|---|

| Increased protein | 1 | 16.7% |

| Providing the necessary protein value to the diet | 1 | 16.7% |

| Highly concentrated and balanced whey protein. | 1 | 16.7% |

| Ideal for increasing your protein intake | 2 | 33.3% |

| Protein synthesis | 1 | 16.7% |

| Property Statement Healthy Approved | Total Supplements in Which This Statement Is Given | Comply with Conditions of Use | No. of Supplements Where the Conditions of Use Are Met | % Supplements Where the Conditions of Use for This Statement Are Met | Degree of Adequacy Statement Yes/No | Reason * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO. | Total | ||||||

| Protein contributes to muscle mass increase | 99 | 97.1% | Yes | 25 | 25.3% | Yes | 5 |

| Yes | 15 | 15.2% | No | 4 | |||

| Yes | 58 | 58.6% | No | 3 | |||

| Yes | 1 | 1% | No | 2 | |||

| Protein helps to maintain muscle mass | 79 | 77.5% | Yes | 24 | 30.4% | Yes | 5 |

| Yes | 27 | 34.2% | No | 4 | |||

| Yes | 21 | 26.6% | No | 3 | |||

| Yes | 7 | 8.9% | No | 2 | |||

| Proteins contribute to the maintenance of normal bones. | 31 | 30.4% | Yes | 11 | 35.5% | Yes | 5 |

| Yes | 12 | 38.7% | No | 4 | |||

| Yes | 4 | 12.9% | No | 3 | |||

| Yes | 4 | 12.9 | No | 2 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodríguez-Hernández, M.D.; Martínez-Sanz, J.M.; García, C.J.; Gabaldón, J.A.; Ferreres, F.; Escribano, M.; Giménez-Monzó, D.; Gil-Izquierdo, Á. Health Claims for Protein Food Supplements for Athletes—The Analysis Is in Accordance with the EFSA’s Scientific Opinion. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1923. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111923

Rodríguez-Hernández MD, Martínez-Sanz JM, García CJ, Gabaldón JA, Ferreres F, Escribano M, Giménez-Monzó D, Gil-Izquierdo Á. Health Claims for Protein Food Supplements for Athletes—The Analysis Is in Accordance with the EFSA’s Scientific Opinion. Nutrients. 2025; 17(11):1923. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111923

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez-Hernández, María Dolores, José Miguel Martínez-Sanz, Carlos Javier García, José Antonio Gabaldón, Federico Ferreres, Miguel Escribano, Daniel Giménez-Monzó, and Ángel Gil-Izquierdo. 2025. "Health Claims for Protein Food Supplements for Athletes—The Analysis Is in Accordance with the EFSA’s Scientific Opinion" Nutrients 17, no. 11: 1923. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111923

APA StyleRodríguez-Hernández, M. D., Martínez-Sanz, J. M., García, C. J., Gabaldón, J. A., Ferreres, F., Escribano, M., Giménez-Monzó, D., & Gil-Izquierdo, Á. (2025). Health Claims for Protein Food Supplements for Athletes—The Analysis Is in Accordance with the EFSA’s Scientific Opinion. Nutrients, 17(11), 1923. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111923