The Prevalence of and Factors Associated with Disordered Eating Among Adult Athletes in Italy and Lebanon

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

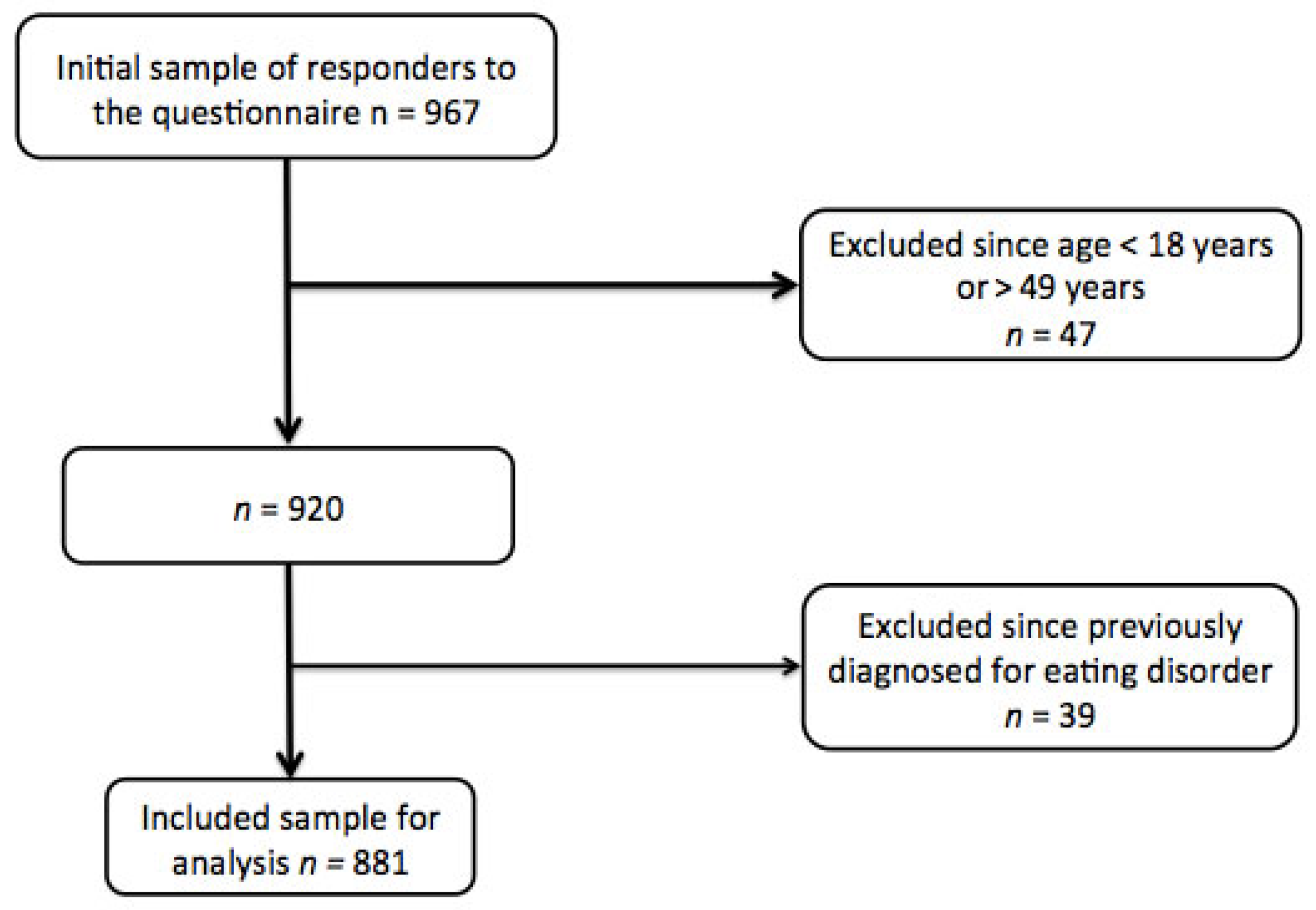

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Questionnaires

2.2.1. General Questionnaire

- Type of sport: according to the frequencies in our sample, the athletes were classified according to their sports discipline as competing in either team sports (i.e., mainly ball games such as football, basketball, volleyball, handball, etc.) or individual ones, categorized as athletics, aesthetics, weightlifting/bodybuilding, and others.

- Level of competition: according to the level of competition at which they practice their sport, the athletes were classified at four different levels: city/province, region/district, national, or international.

- Years of athletic experience: the duration for which the athlete has been practicing a specific sport at a competitive level, expressed in years.

- Training volume: the number of hours per week spent in training sessions.

2.2.2. Eating Attitudes

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings and Concordance with Previous Literature

4.2. Clinical Implications

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.4. New Directions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berthelot, G.; Sedeaud, A.; Marck, A.; Antero-Jacquemin, J.; Schipman, J.; Saulière, G.; Marc, A.; Desgorces, F.D.; Toussaint, J. Has Athletic Performance Reached its Peak? Sports Med. 2015, 45, 1263–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchomel, T.J.; Nimphius, S.; Stone, M. The Importance of Muscular Strength in Athletic Performance. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 1419–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trecroci, A.; Formenti, D.; Moran, J.; Pedreschi, D.; Rossi, A. Editorial: Factors Affecting Performance and Recovery in Team Sports: A Multidimensional Perspective. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 877879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Arora, M.K.; Boruah, B. The role of the six factors model of athletic mental energy in mediating athletes’ well-being in competitive sports. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guth, L.M.; Roth, S. Genetic influence on athletic performance. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2013, 25, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, R.; Straebler, S.; Cooper, Z.; Fairburn, C. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Eating Disorders. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 33, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rome, E.S.; Ammerman, S. Medical complications of eating disorders: An update. J. Adolesc. Health 2003, 33, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, D.A.; Martin, C.K.; Stewart, T. Psychological aspects of eating disorders. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2004, 18, 1073–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keel, P.K.; Forney, K.J. Psychosocial risk factors for eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2013, 46, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuerda, C.; Vasiloglou, M.F.; Arhip, L. Nutritional Management and Outcomes in Malnourished Medical Inpatients: Anorexia Nervosa. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fricke, C.; Voderholzer, U. Endocrinology of Underweight and Anorexia Nervosa. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forney, K.J.; Buchman-Schmitt, J.M.; Keel, P.K.; Frank, G.K. The Medical Complications Associated with Purging. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2016, 49, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, J.; Wu, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhu, Y.; Jin, H.; Zhang, H.; Wan, Y.; Li, C.; Yu, D. An update on the prevalence of eating disorders in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eat. Weight Disord. 2021, 27, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulik, C.M. Eating disorders in adolescents and young adults. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2002, 11, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas-Padilla, I.C.; Portela-Pino, I.; Martínez-Patiño, M.J. The Risk of Eating Disorders in Adolescent Athletes: How We Might Address This Phenomenon? Sports 2024, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Torstveit, M.K. Prevalence of eating disorders in elite athletes is higher than in the general population. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2004, 14, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Ghoch, M.; Soave, F.; Calugi, S.; Dalle Grave, R. Eating disorders, physical fitness and sport performance: A systematic review. Nutrients 2013, 5, 5140–5160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, M.; Galvani, C.; Capelli, C.; Lanza, M.; El Ghoch, M.; Calugi, S.; Dalle Grave, R. Physical fitness before and after weight restoration in anorexia nervosa. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2013, 53, 396–402. [Google Scholar]

- Reba-Harreleson, L.; Von Holle, A.; Hamer, R.M.; Swann, R.; Reyes, M.L.; Bulik, C. Patterns and Prevalence of Disordered Eating and Weight Control Behaviors in Women Ages 25–45. Eat. Weight Disord. 2009, 14, e190–e198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, G.C.; Selzer, R.; Coffey, C.; Carlin, J.B.; Wolfe, R. Onset of adol escent eating disorders: Population based cohort study over 3 years. BMJ 1999, 318, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.D. Disordered eating in active and athletic women. Clin. Sports Med. 1994, 13, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.N.; Pumariega, A.J. Culture and eating disorders: A historical and cross-cultural review. Psychiatry Interpers. Biol. Process. 2001, 64, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancine, R.P.; Gusfa, D.W.; Moshrefi, A.; Kennedy, S.F. Prevalence of disordered eating in athletes categorized by emphasis on leanness and activity type—A systematic review. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 8, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garner, D.M.; Olmsted, M.P.; Bohr, Y.; Garfinkel, P.E. The eating attitudes test: Psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychol. Med. 1982, 12, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uriegas, N.A.; Winkelmann, Z.K.; Pritchett, K.; Torres-McGehee, T.M. Examining Eating Attitudes and Behaviors in Collegiate Athletes, the Association Between Orthorexia Nervosa and Eating Disorders. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 763838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gargari, B.P.; Kooshavar, D.; Sajadi, N.S.; Safoura, S.; Behzad, M.H.; Shahrokhi, H. Disordered Eating Attitudes and Their Correlates among Iranian High School Girls. Health Promot. Perspect. 2011, 1, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Lu, M.; Tian, L.; Lu, W.; Meng, F.; Chen, C.; Tang, T.; He, L.; Yao, Y. Prevalence of disordered eating attitudes among University students in Wuhu, China. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 32, 1752–1757. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saleh, R.N.; Salameh, R.A.; Yhya, H.H.; Sweileh, W.M. Disordered eating attitudes in female students of An-Najah National University: A cross-sectional study. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sabbah, H.; Muhsineh, S. Disordered Eating Attitudes and Exercise Behavior among Female Emirati College Students in the United Arab Emirates: A Cross-Sectional Study. Arab. J. Nutr. Exerc. AJNE 2017, 1, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, F.; Ahmad, L. Prevalence of disordered eating attitudes among adolescent girls in Arar City, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Health Psychol. Res. 2018, 6, 7444. [Google Scholar]

- Raja, N.A.A.; Osman, N.A.; Alqethami, A.M.; Abd El-Fatah, N.K. The relationship between the high-risk disordered eating and social network navigation among Saudi college females during the COVID pandemic. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 949051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engdyhu, B.M.; Gonete, K.A.; Mengistu, B.; Worku, N. Disordered eating attitude and associated factors among late adolescent girls in Gondar city, northwest Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1425986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsheweir, A.; Goyder, E.; Alnooh, G.; Caton, S.J. Prevalence of Eating Disorders and Disordered Eating Behaviours amongst Adolescents and Young Adults in Saudi Arabia: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanlier, N.; Varli, S.N.; Macit, M.S.; Mortas, H.; Tatar, T. Evaluation of disordered eating tendencies in young adults. Eat. Weight. Disord. Stud. 2017, 22, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stackeová, D.; Barešová, T.; Přibylová, B. A pilot study of a modification EAT-26 questionnaire for screening pathological eating behavior in competitive athletes. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1166129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Kloub, M.I.; Al-Khawaldeh, O.A.; Albashtawy, M.; Batiha, A.; Al-Haliq, M. Disordered eating in Jordanian adolescents. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2019, 25, e12694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nohara, N.; Hiraide, M.; Horie, T.; Takakura, S.; Hata, T.; Sudo, N.; Yoshiuchi, K. The optimal cut-off score of the Eating Attitude Test-26 for screening eating disorders in Japan. Eat. Weight Disord. 2024, 29, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, C.; Khoury, C.; Salameh, P.; Sacre, H.; Hallit, R.; Kheir, N.; Obeid, S.; Hallit, S. Validation of the Arabic version of the Eating Attitude Test in Lebanon: A population study. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 4132–4143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotti, A.; Lazzari, R. Validation and reliability of the Italian EAT-26. Eat. Weight. Disord. 1998, 3, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kampouri, D.; Kotopoulea-Nikolaidi, M.; Daskou, S.; Giannopoulou, I. Prevalence of disordered eating in elite female athletes in team sports in Greece. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2019, 19, 1267–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosendahl, J.; Bormann, B.; Aschenbrenner, K.; Aschenbrenner, F.; Strauss, B. Dieting and disordered eating in German high school athletes and non-athletes. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2009, 19, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravi, S.; Ihalainen, J.K.; Taipale-Mikkonen, R.S.; Kujala, U.M.; Waller, B.; Mierlahti, L.; Lehto, J.; Valtonen, M. Self-Reported Restrictive Eating, Eating Disorders, Menstrual Dysfunction, and Injuries in Athletes Competing at Different Levels and Sports. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yılmaz, M.N.; Dundar, C. The relationship between orthorexia nervosa, anxiety, and self-esteem: A cross-sectional study in Turkish faculty members. BMC Psychol. 2022, 10, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, P.; Harris, L.M. The Sporting Body: Body Image and Eating Disorder Symptomatology Among Female Athletes from Leanness Focused and Nonleanness Focused Sports. J. Psychol. 2015, 149, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousselet, M.; Guérineau, B.; Paruit, M.C.; Guinot, M.; Lise, S.; Destrube, B.; Ruffio-Thery, S.; Dominguez, N.; Brisseau-Gimenez, S.; Dubois, V.; et al. Disordered eating in French high-level athletes: Association with type of sport, doping behavior, and psychological features. Eat. Weight Disord. 2017, 22, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghazzawi, H.A.; Alhaj, O.A.; Nemer, L.S.; Amawi, A.T.; Trabelsi, K.; Jahrami, H. The Prevalence of “at Risk” Eating Disorders among Athletes in Jordan. Sports 2022, 10, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jumayan, A.A.; Al-Eid, N.A.; AlShamlan, N.A.; AlOmar, R.S. revalence and associated factors of eating disorders in patrons of sport centers in Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Community Med. 2021, 28, 94–102. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazzawi, H.A.; Nimer, L.S.; Haddad, A.J.; Alhaj, O.A.; Amawi, A.T.; Pandi-Perumal, S.R.; Trabelsi, K.; Seeman, M.V.; Jahrami, H. A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of the prevalence of self-reported disordered eating and associated factors among athletes worldwide. J. Eat. Disord. 2024, 12, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.G. Eating disorders and disordered eating in different cultures. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 1995, 18, 537–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosley, P.E. Bigorexia: Bodybuilding and muscle dysmorphia. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2009, 17, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonci, C.M.; Bonci, L.J.; Granger, L.R.; Johnson, C.L.; Malina, R.M.; Milne, L.W.; Ryan, R.R.; Vanderbunt, E.M. National athletic trainers’ association position statement: Preventing, detecting, and managing disordered eating in athletes. J. Athl. Train. 2008, 43, 80–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravaldi, C.; Vannacci, A.; Zucchi, T.; Mannucci, E.; Cabras, P.L.; Boldrini, M.; Murciano, L.; Rotella, C.M.; Ricca, V. Eating disorders and body image disturbances among ballet dancers, gymnasium users and body builders. Psychopathology 2003, 36, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vásquez-Díaz, F.; Aguayo-Muela, D.C.; Radesca, K.; Muñoz-Andradas, G.; Domínguez-Balmaseda, D. Prevalence of Disordered Eating Risk Attitudes in Youth Elite Male and Female Football Players. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krentz, E.M.; Warschburger, P. Sports-related correlates of disordered eating in aesthetic sports. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2011, 12, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (n = 881) | Males (n = 520) | Females (n = 361) | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 24.8 (6.5) | 25.1 (6.4) | 24.4 (6.6) | p = 0.158 |

| Education | X2 = 0.650; p = 0.420 | |||

| Lower education | 529 (60.0) | 318 (61.2) | 211 (58.3) | |

| Higher education | 352 (40.0) | 202 (38.8) | 150 (41.6) | |

| Marital status | X2 = 2.366; p = 0.124 | |||

| Not married | 744 (84.4) | 431 (82.9) | 313 (86.7) | |

| Married/cohabiting | 137 (15.6) | 89 (17.1) | 48 (13.3) | |

| Competitive level | X2 = 7.717; p = 0.052 | |||

| City/provincial | 238 (27.0) | 152 (29.2) | 86 (23.8) | |

| National | 296 (33.6) | 161 (31.0) | 135 (37.4) | |

| Regional | 238 (27.0) | 149 (28.7) | 89 (24.7) | |

| International | 109 (12.4) | 58 (11.2) | 51 (14.1) | |

| Nationality | X2 = 0.006; p = 0.938 | |||

| Italian | 721 (81.8) | 426 (81.9) | 295 (81.7) | |

| Lebanese | 160 (18.2) | 94 (18.1) | 66 (18.3) | |

| Years of athletic experience | 11.5 (6.5) | 11.7 (6.6) | 11.1 (6.3) | p = 0.146 |

| Volume of training (hours/week) | 9.3 (6.8) | 9.5 (7.4) | 9.1 (5.9) | p = 0.425 |

| Males | Females | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAT-26 < 17 (n = 483) | EAT-26 ≥ 17 (n = 37) | Significance | EAT-26 < 17 (n = 320) | EAT-26 ≥ 17 (n = 41) | Significance | |

| Age (years) | 24.7 (6.1) | 28.8 (8.9) | p = 0.009 | 24.3 (6.5) | 25.2 (7.2) | p = 0.448 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.4 (2.69) | 24.8 (4.1) | p = 0.048 | 21.6 (2.9) | 22.8 (2.9) | p = 0.019 |

| Level of education | X2 = 9.116; p = 0.003 | X2 = 0.995; p = 0.318 | ||||

| Lower education | 304 (62.9) | 14 (37.8) | 190 (59.4) | 21 (51.2) | ||

| Higher education | 179 (37.1) | 23 (62.2) | 130 (40.6) | 20 (48.8) | ||

| Marital status | X2 = 0.091; p = 0.762 | X2 = 0.072; p = 0.789 | ||||

| Not married | 401 (83.0) | 30 (81.1) | 278 (86.9) | 35 (85.4) | ||

| Married or co-habiting | 82 (17.0) | 7 (18.9) | 42 (13.1) | 6 (14.6) | ||

| Type of sport | X2 = 14.817; p = 0.005 | X2 = 2.363; p = 0.669 | ||||

| Team sports | 258 (53.4) | 14 (37.8) | 128 (40.0) | 15 (36.6) | ||

| Athletics | 91 (18.8) | 8 (21.6) | 91 (28.4) | 11 (26.8) | ||

| Aesthetics | 15 (3.1) | 4 (10.8) | 35 (10.9) | 7 (17.1) | ||

| Weightlifting or bodybuilding | 33 (6.8) | 7 (18.9) | 14 (4.4)) | 3 (7.3) | ||

| Other | 86(17.8) | 4 (10.8) | 52 (16.3) | 5 (12.2) | ||

| Competitive level | X2 = 2.763; p = 0.430 | X2 = 1.418; p = 0.701 | ||||

| City/province | 142 (19.4) | 10 (27.0) | 79 (24.7) | 7 (17.1) | ||

| Regional | 142 (29.4) | 7 (18.9) | 79 (24.7) | 10 (24.4) | ||

| National | 146 (30.2) | 15 (40.5) | 117 (36.6) | 18 (43.9) | ||

| International | 53 (11.0) | 5 (13.5) | 45 (14.1) | 6 (14.6) | ||

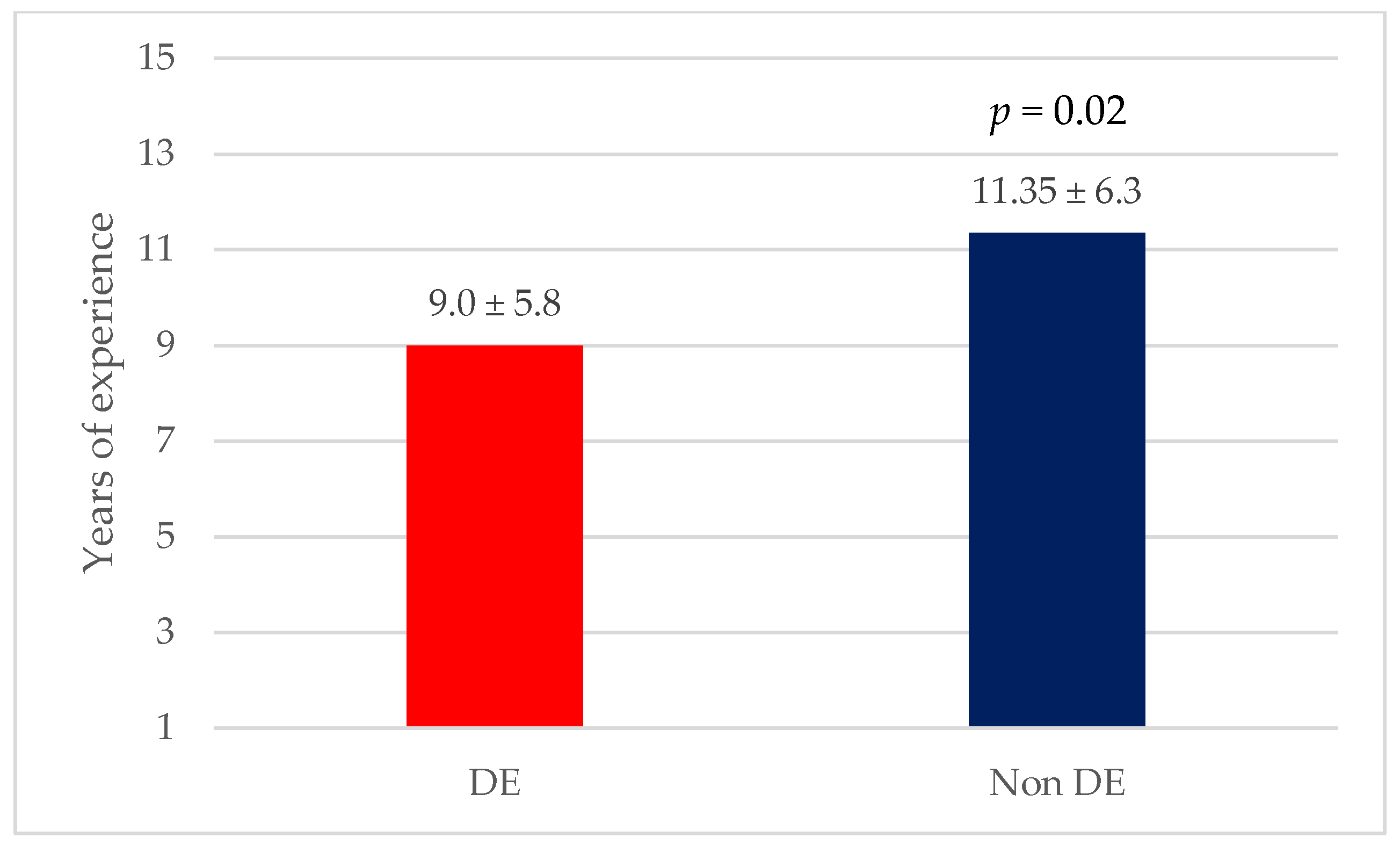

| Years of athletic experience | 11.7 (6.5) | 12.5 (8.7) | p = 0.592 | 11.4(6.3) | 9.0 (5.8) | p = 0.020 |

| Volume of training (hours/week) | 9.3 (7.3) | 11.6 (8.5) | p = 0.113 | 9.1 (6.0) | 9.4 (4.7) | p = 0.697 |

| Males | Females | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | ||

| Age | 1.06 (0.99–1.13) | 1.01 (0.95–1.08) |

| BMI | 1.09 (0.98–1.21) | 1.13 (0.99–1.28) |

| Level of education | ||

| Lower education | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Higher education | 2.23 (1.04–4.81) * | 1.45 (0.66–3.18) |

| Type of sport | ||

| Team sports | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Athletics | 1.12 (0.38–3.29) | 0.70 (0.25–1.95) |

| Aesthetics | 3.69 (0.98–13.93) | 1.78 (0.62–5.07) |

| Weightlifting or bodybuilding | 3.23 (1.03–10.08) * | 0.78 (0.17–3.62) |

| Other | 0.66 (0.20–2.23) | 0.55 (0.17–1.76) |

| Competitive level | ||

| City/province | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Regional | 0.76 (0.27–2.17) | 1.98 (0.66–5.92) |

| National | 1.39 (0.56–3.43) | 2.05 (0.75–5.60) |

| International | 0.75 (0.19–2.95) | 2.62 (0.65–10.58) |

| Years of athletic experience | 0.99 (0.94–1.05) | 0.92 (0.86–0.98) * |

| Volume of training (hours/week) | 1.03 (0.99–1.07) | 1.01 (0.95–1.08) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cavedon, V.; Kreidieh, D.; Milanese, C.; Itani, L.; Pellegrini, M.; Saadeddine, D.; Berri, E.; El Ghoch, M. The Prevalence of and Factors Associated with Disordered Eating Among Adult Athletes in Italy and Lebanon. Nutrients 2025, 17, 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17010191

Cavedon V, Kreidieh D, Milanese C, Itani L, Pellegrini M, Saadeddine D, Berri E, El Ghoch M. The Prevalence of and Factors Associated with Disordered Eating Among Adult Athletes in Italy and Lebanon. Nutrients. 2025; 17(1):191. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17010191

Chicago/Turabian StyleCavedon, Valentina, Dima Kreidieh, Chiara Milanese, Leila Itani, Massimo Pellegrini, Dana Saadeddine, Elisa Berri, and Marwan El Ghoch. 2025. "The Prevalence of and Factors Associated with Disordered Eating Among Adult Athletes in Italy and Lebanon" Nutrients 17, no. 1: 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17010191

APA StyleCavedon, V., Kreidieh, D., Milanese, C., Itani, L., Pellegrini, M., Saadeddine, D., Berri, E., & El Ghoch, M. (2025). The Prevalence of and Factors Associated with Disordered Eating Among Adult Athletes in Italy and Lebanon. Nutrients, 17(1), 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17010191