Clinical Presentations of Celiac Disease: Experience of a Single Italian Center

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

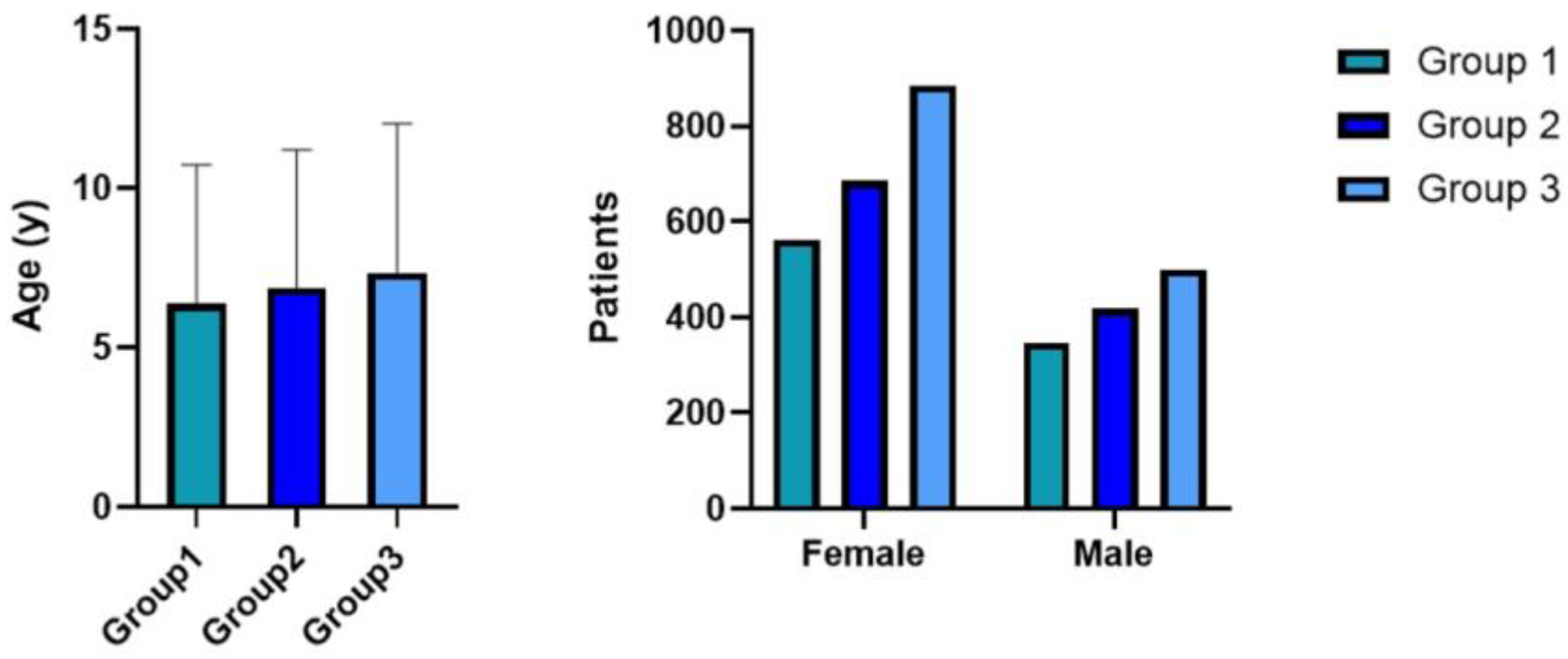

- Group 1 (n = 909): patients who received a diagnosis from 1 March 2011 to 30 April 2015;

- Group 2 (n = 1103): patients who received a diagnosis from 1 May 2015 to 30 May 2019;

- Group 3 (n = 1384): patients who received a diagnosis from 1 June 2019 to 22 June 2023.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, P.; Arora, A.; Strand, T.A.; Leffler, D.A.; Catassi, C.; Green, P.H.; Kelly, C.P.; Ahuja, V.; Makharia, G.K. Global Prevalence of Celiac Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 16, 823–836.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatti, S.; Lionetti, E.; Balanzoni, L.; Verma, A.K.; Galeazzi, T.; Gesuita, R.; Scattolo, N.; Cinquetti, M.; Fasano, A.; Catassi, C.; et al. Increased Prevalence of Celiac Disease in School-age Children in Italy. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lionetti, E.; Pjetraj, D.; Gatti, S.; Catassi, G.; Bellantoni, A.; Boffardi, M.; Cananzi, M.; Cinquetti, M.; Francavilla, R.; Malamisura, B.; et al. Prevalence and detection rate of celiac disease in Italy: Results of a SIGENP multicenter screening in school-age children. Dig. Liver Dis. 2023, 55, 608–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catassi, C.; Verdu, E.F.; Bai, J.C.; Lionetti, E. Coeliac disease. Lancet 2022, 399, 2413–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludvigsson, J.F.; Leffler, D.A.; Bai, J.C.; Biagi, F.; Fasano, A.; Green, P.H.; Hadjivassiliou, M.; Kaukinen, K.; Kelly, C.P.; Leonard, J.N.; et al. The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut 2013, 62, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kalleveen, M.W.; de Meij, T.; Plotz, F.B. Clinical spectrum of paediatric coeliac disease: A 10-year single-centre experience. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2018, 177, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almallouhi, E.; King, K.S.; Patel, B.; Wi, C.; Juhn, Y.J.; Murray, J.A.; Absah, I. Increasing Incidence and Altered Presentation in a Population-based Study of Pediatric Celiac Disease in North America. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 65, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roma, E.; Panayiotou, J.; Karantana, H.; Constantinidou, C.; Siakavellas, S.I.; Krini, M.; Syriopoulou, V.P.; Bamias, G. Changing pattern in the clinical presentation of pediatric celiac disease: A 30-year study. Digestion 2009, 80, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedretti, M.; Sbravati, F.; Allegri, D.; Labriola, F.; Lombardo, V.; Spisni, E.; Zarbo, C.; Alvisi, P. Is the clinical pattern of pediatric celiac disease changing? A thirty-years real-life experience of an Italian center. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2021, 47, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revised criteria for diagnosis of coeliac disease. Report of Working Group of European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. Arch. Dis. Child. 1990, 65, 909–911. [CrossRef]

- Husby, S.; Koletzko, S.; Korponay-Szabo, I.R.; Mearin, M.L.; Phillips, A.; Shamir, R.; Troncone, R.; Giersiepen, K.; Branski, D.; Catassi, C.; et al. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2012, 54, 136–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husby, S.; Koletzko, S.; Korponay-Szabo, I.; Kurppa, K.; Mearin, M.L.; Ribes-Koninckx, C.; Shamir, R.; Troncone, R.; Auricchio, R.; Castillejo, G.; et al. European Society Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Guidelines for Diagnosing Coeliac Disease 2020. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2020, 70, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolia, R.; Thapar, N. Celiac Disease in Children: A 2023 Update. Indian J. Pediatr. 2024, 91, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trovato, C.M.; Montuori, M.; Oliva, S.; Cucchiara, S.; Cignarelli, A.; Sansone, A. Assessment of public perceptions and concerns of celiac disease: A Twitter-based sentiment analysis study. Dig. Liver Dis. 2020, 52, 464–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Biase, A.R.; Marasco, G.; Ravaioli, F.; Colecchia, L.; Dajti, E.; Lecis, M.; Passini, E.; Alemanni, L.V.; Festi, D.; Iughetti, L.; et al. Clinical Presentation of Celiac Disease and Diagnosis Accuracy in a Single-Center European Pediatric Cohort over 10 Years. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, C.M.; Raucci, U.; Valitutti, F.; Montuori, M.; Villa, M.P.; Cucchiara, S.; Parisi, P. Neuropsychiatric manifestations in celiac disease. Epilepsy Behav. 2019, 99, 106393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glimberg, I.; Haggard, L.; Lebwohl, B.; Green, P.H.R.; Ludvigsson, J.F. The prevalence of celiac disease in women with infertility—A systematic review with meta-analysis. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2021, 20, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castano, M.; Gomez-Gordo, R.; Cuevas, D.; Nunez, C. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prevalence of Coeliac Disease in Women with Infertility. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, L.; Pellegrino, R.; Sciorio, C.; Barone, B.; Gravina, A.G.; Santonastaso, A.; Mucherino, C.; Astretto, S.; Napolitano, L.; Aveta, A.; et al. Erectile and sexual dysfunction in male and female patients with celiac disease: A cross-sectional observational study. Andrology 2022, 10, 910–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez Solis, D.; Cilleruelo Pascual, M.L.; Ochoa Sangrador, C.; Garcia Burriel, J.I.; Sanchez-Valverde Visus, F.; Eizaguirre Arocena, F.J.; Garcia Calatayud, S.; Martinez-Ojinaga Nodal, E.; Donat Aliaga, E.; Barrio Torres, J.; et al. Spanish National Registry of Paediatric Coeliac Disease: Changes in the Clinical Presentation in the 21st Century. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2022, 74, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, M.; Baker, R.D.; Ly, E.K.; Kozielski, R.; Baker, S.S. Presenting Pattern of Pediatric Celiac Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2016, 62, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, A.; Fahey, L.; Sun, Q.; Regis, S.; Khavari, N.; Jericho, H.; Badalyan, V.; Absah, I.; Verma, R.; Leonard, M.M.; et al. Clinical presentation and factors associated with gluten exposure in children with celiac disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2024, 79, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soldera, J.; Coelho, G.P.; Heinrich, C.F. Life-Threatening Diarrhea in an Elderly Patient. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 26–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ancona, S.; Bianchin, S.; Zampatti, N.; Nosratian, V.; Bigatti, C.; Ferro, J.; Trambaiolo Antonelli, C.; Viglizzo, G.; Gandullia, P.; Malerba, F.; et al. Cutaneous Disorders Masking Celiac Disease: Case Report and Mini Review with Proposal for a Practical Clinical Approach. Nutrients 2023, 16, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, I.M.; Brooks, J.K.; Ghita, I.; Sultan, A.S.; MacKelfresh, J.B. Oral and cutaneous pemphigus vulgaris: An atypical clinical presentation. Gen. Dent. 2022, 70, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Tiberti, C.; Montuori, M.; Panimolle, F.; Trovato, C.M.; Anania, C.; Valitutti, F.; Vestri, A.R.; Lenzi, A.; Cucchiara, S.; Morano, S. Screening for Type 1 Diabetes-, Thyroid-, Gastric-, and Adrenal-Specific Humoral Autoimmunity in 529 Children and Adolescents With Celiac Disease at Diagnosis Identifies as Positive One in Every Nine Patients. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, e10–e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catassi, C.; Vincentini, O.; Pricci, F.; Agrimi, U.; Silano, M.; Bosi, E. Pediatric screening for type 1 diabetes and celiac disease: The future is today in Italy. Minerva Pediatr. 2024, 76, 461–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosi, E.; Catassi, C. Screening type 1 diabetes and celiac disease by law. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2024, 12, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panetta, F.; Nobili, V.; Sartorelli, M.R.; Papa, R.E.; Ferretti, F.; Alterio, A.; Diamanti, A. Celiac disease in pediatric patients with autoimmune hepatitis: Etiology, diagnosis, and management. Paediatr. Drugs 2012, 14, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiberti, C.; Panimolle, F.; Borghini, R.; Montuori, M.; Trovato, C.M.; Filardi, T.; Lenzi, A.; Picarelli, A. Type 1 diabetes, thyroid, gastric and adrenal humoral autoantibodies are present altogether in almost one third of adult celiac patients at diagnosis, with a higher frequency than children and adolescent celiac patients. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 55, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symptoms | n | Group 1 (n = 909) | Group 2 (n = 1103) | Group 3 (n = 1384) | χ2 (G1-G2-G3) | χ2 (G1-G3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diarrhea | 1159 | 332 (36.5%) | 386 (35%) | 441 (31.8%) | χ2 = 5.84 p = 0.053 | χ2 = 5.33 p = 0.021 |

| Bloating | 2636 | 629 (69.1%) | 909 (82.4%) | 1098 (79.3%) | χ2 = 54.05 p < 0.00001 | χ2 = 30.32 p < 0.00001 |

| Abdominal pain | 1853 | 526 (57.8%) | 650 (58.9%) | 677 (48.9%) | χ2 = 30.28 p < 0.00001 | χ2 = 46.20 p < 0.00001 |

| Vomiting | 931 | 236 (25.9%) | 321 (29.1%) | 356 (35.7%) | χ2 = 4.10 p = 0.128 | χ2 = 0.016 p = 0.8978 |

| Constipation | 1017 | 248 (27.2%) | 328 (29.7%) | 441 (31.8%) | χ2 = 5.52 p = 0.063 | χ2 = 7.55 p = 0.006 |

| Weight loss | 703 | 219 (24%) | 207 (18.7%) | 277 (20%) | χ2 = 9.27 p = 0.009 | χ2 = 5.38 p = 0.0204 |

| Failure to thrive | 1650 | 464 (51%) | 576 (52.2%) | 610 (44%) | χ2 = 19.31 p = 0.00006 | χ2 = 10.69 p = 0.0011 |

| Change in mood | 852 | 250 (27,5%) | 270 (24.4%) | 332 (24%) | χ2 = 3.92 p = 0.140 | χ2 = 3.58 p = 0.0586 |

| Iron deficiency anemia | 1166 | 341 (37.5%) | 418 (37.8%) | 407 (29.4%) | χ2 = 25.18 p < 0.00001 | χ2 = 16.39 p = 0.00001 |

| Hypertransaminasemia | 153 | 37 (4%) | 55 (4.9%) | 61 (4.4%) | χ2 = 1.023 p = 0.599 | χ2 = 0.15 p = 0.6963 |

| Recurrent aphthous stomatitis | 212 | 69 (7.6%) | 70 (6.3%) | 73 (5.3%) | χ2 = 5.058 p = 0.079 | χ2 = 5.064 p = 0.0244 |

| Dental enamel defects | 210 | 45 (4.9%) | 102 (9.2%) | 63 (4.5%) | χ2 = 26.58 p < 0.00001 | χ2 = 0.194 p = 0.6596 |

| Celiac crisis | 58 | 33 (3.6%) | 14 (1.2%) | 11 (0.8%) | χ2 = 28.15 p < 0.00001 | χ2 = 23.43 p < 0.00001 |

| Asymptomatic | 85 | 31 (3.4%) | 13 (1.2%) | 41 (2.9%) | χ2 = 12.19 p = 0.0022 | χ2 = 0.362 p = 0.5475 |

| Associated Condition | n | Group 1 (n = 909) | Group 2 (n= 1103) | Group 3 (n = 1384) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 Diabetes | 213 | 45 (4.9%) | 102 (9.2%) | 66 (4.7%) |

| Chronic autoimmune thyroiditis | 86 | 45 (4.9%) | 17 (1.5%) | 24 (1.73%) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 32 | 12 (1.32%) | 5 (0.45%) | 15 (1%) |

| Down Syndrome | 40 | 7 (0.77%) | 18 (1.63%) | 15 (1%) |

| Turner Syndrome | 5 | 1 (0.11%) | 4 (0.36%) | 0 |

| Other Syndromes | 7 | 1 (0.11%) | 3 (0.27%) | 3 (0.2%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trovato, C.M.; Ferretti, F.; Delli Bovi, A.P.; Elefante, G.; Ancinelli, M.; Bolasco, G.; Capriati, T.; Cardile, S.; Knafelz, D.; Bracci, F.; et al. Clinical Presentations of Celiac Disease: Experience of a Single Italian Center. Nutrients 2025, 17, 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17010129

Trovato CM, Ferretti F, Delli Bovi AP, Elefante G, Ancinelli M, Bolasco G, Capriati T, Cardile S, Knafelz D, Bracci F, et al. Clinical Presentations of Celiac Disease: Experience of a Single Italian Center. Nutrients. 2025; 17(1):129. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17010129

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrovato, Chiara Maria, Francesca Ferretti, Anna Pia Delli Bovi, Giovanna Elefante, Monica Ancinelli, Giulia Bolasco, Teresa Capriati, Sabrina Cardile, Daniela Knafelz, Fiammetta Bracci, and et al. 2025. "Clinical Presentations of Celiac Disease: Experience of a Single Italian Center" Nutrients 17, no. 1: 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17010129

APA StyleTrovato, C. M., Ferretti, F., Delli Bovi, A. P., Elefante, G., Ancinelli, M., Bolasco, G., Capriati, T., Cardile, S., Knafelz, D., Bracci, F., Alterio, A., Malamisura, M., Grosso, S., De Angelis, P., & Diamanti, A. (2025). Clinical Presentations of Celiac Disease: Experience of a Single Italian Center. Nutrients, 17(1), 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17010129