Why Acute Undernutrition? A Qualitative Exploration of Food Preferences, Perceptions and Factors Underlying Diet in Adolescent Girls in Rural Communities in Nigeria

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

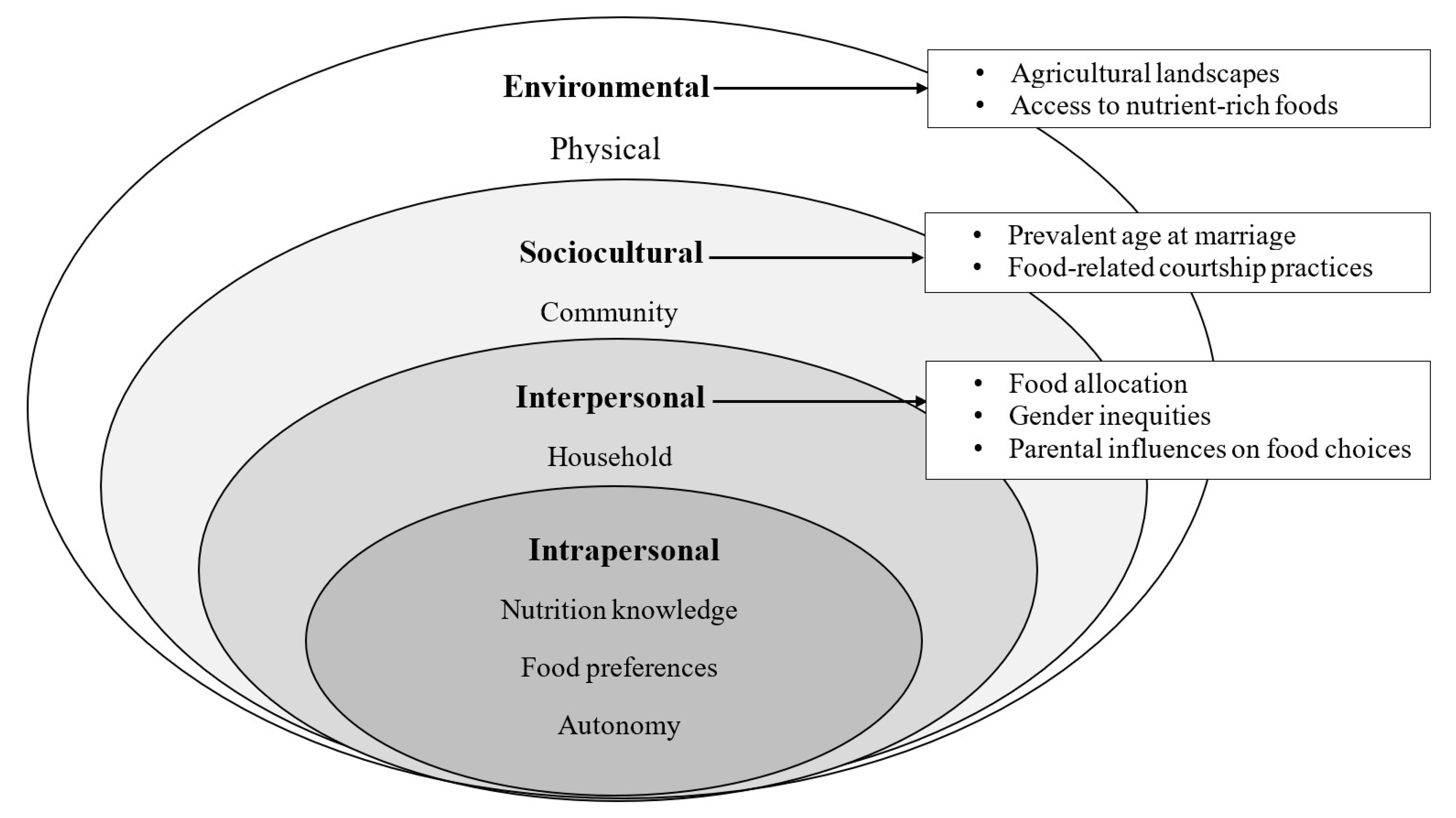

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.2. Study Design, Area and Sites

2.3. Study Population

3. Data Management

3.1. Data-Collection Instrument

3.2. Data Analyses

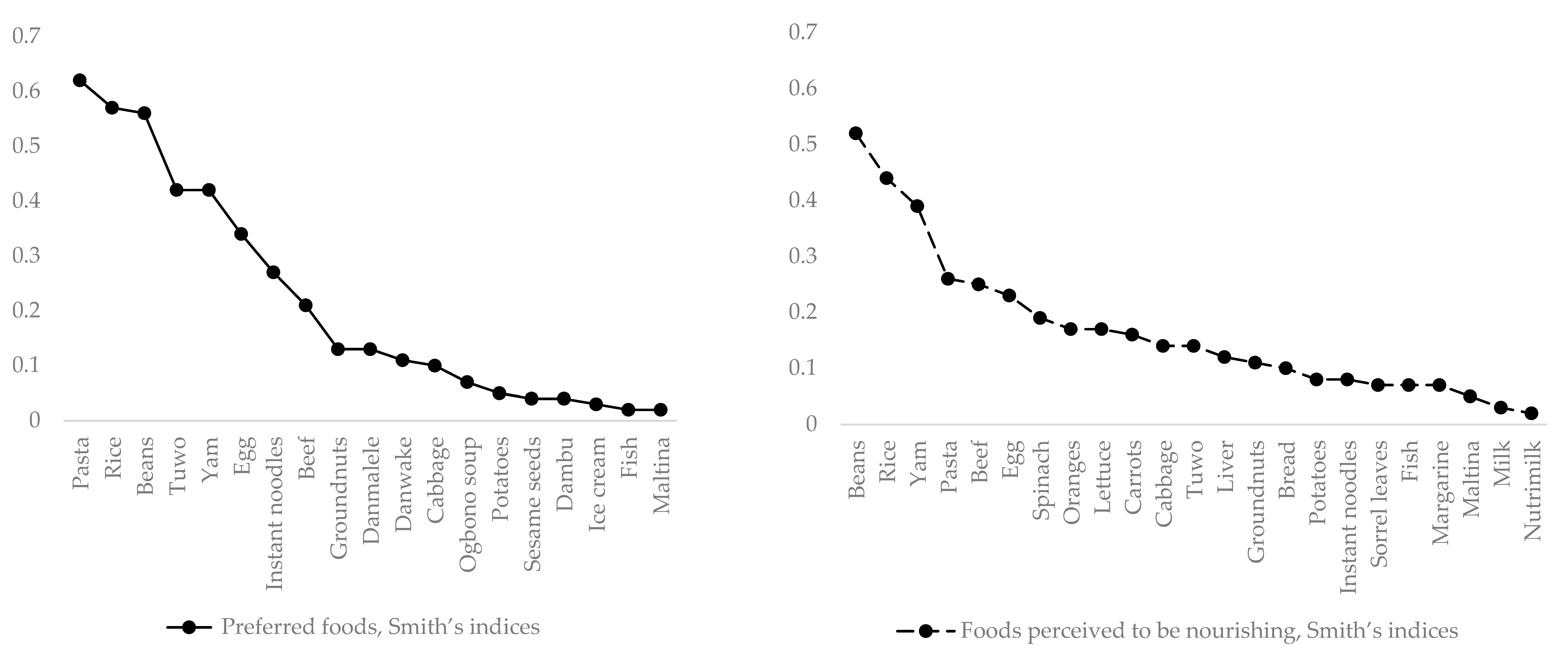

4. Statistical Analyses

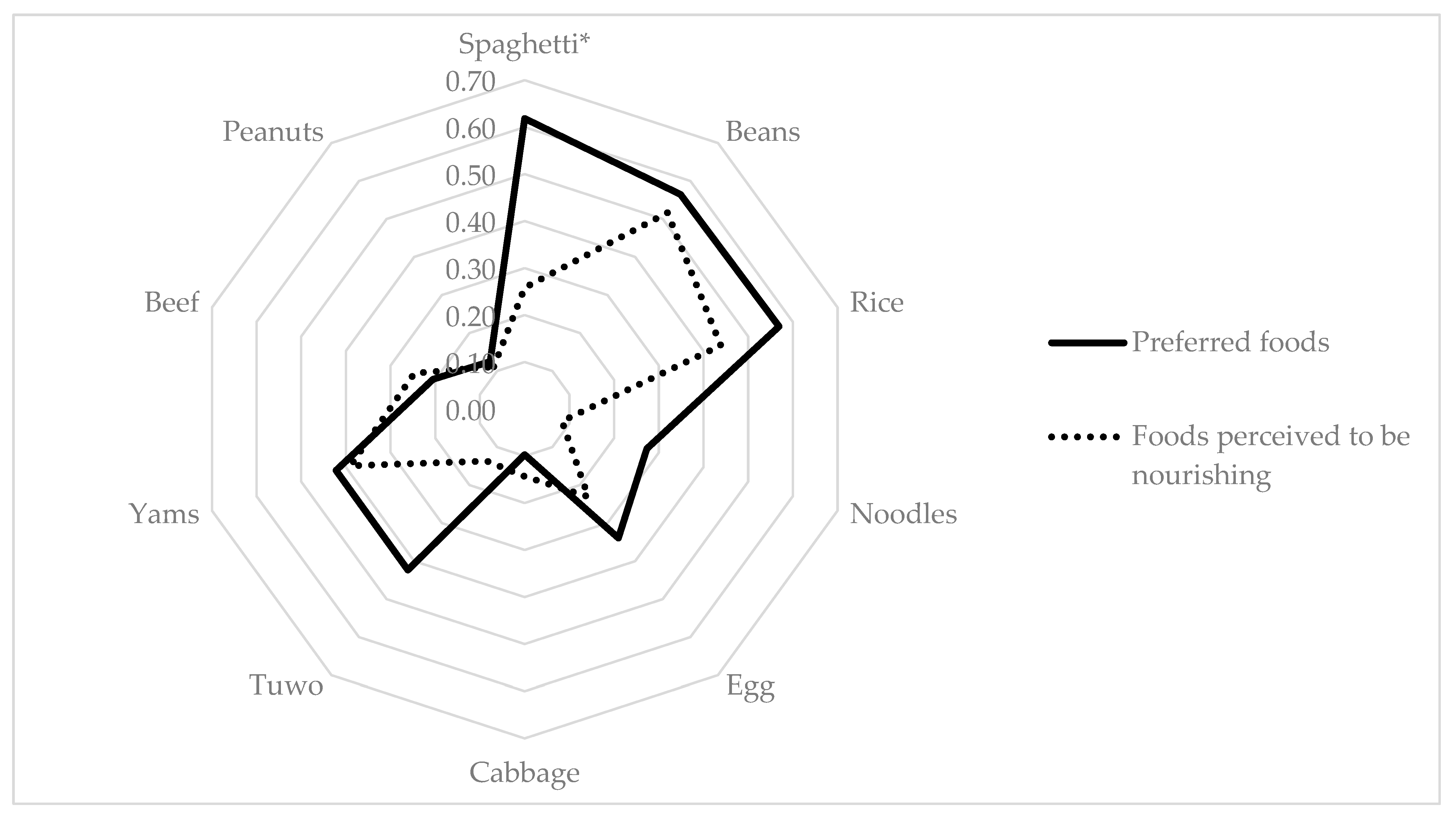

5. Results

5.1. Study Themes

5.2. Knowledge of Basic Concepts in Nutrition

“Pepper, salt and maggi [bouillon cube]” (Adolescent, 14 years, Darazo LGA)

“Rice, talea [spaghetti], gwate [porridge], tuwo, Indomie [noodles], beans porridge, offals and meat” (Adolescent, 11 years, Darazo LGA)

“Maggi [bouillon cubes], salt, oil, pepper and curry” (Adolescent,13 years, Ningi LGA)

“Milk [fresh cow’s milk and evaporated, unsweetened], vegetables, pepper soup” (Adolescent, 14 years, Tafawa Balewa LGA)

Energy giving foods and body-building foods” (Adolescent, 14 years, Alkaleri LGA)

“Foods that make us grow fat” (Adolescent, 12 years, Alkaleri LGA)

5.3. Foods That Girls and Women Should Eat

“Eggs, noodles (instant), beans, meat and macaroni” (Adolescent, 12 years, Gamawa LGA)

“I don’t know that there is any food specifically that girls and women should eat” (Adolescent, 12 years, Darazo LGA)

“Oranges, carrots, meat, fish and gwaten wake [bean porridge]” (Adolescent, 15 years, Darazo LGA)

“Any type of food available, as far as they are all food, we eat them” (Adolescent, 12 years, Shira LGA)

5.4. Reasons for Food Preferences

“They are tasty, they promote health, they make people grow fat, they give blood” (Adolescent, 12 years, Tafawa Balewa LGA)

“I love ice cream because it is chilled and cools me down when I take it. After eating a meal, the sweet taste of ice cream is pleasurable” (Adolescent, 12 years, Darazo LGA)

“I like jollof rice and jollof spaghetti because I enjoy chewing them, unlike tuwo [stiff cereal pudding] that is swallowed [without chewing]” (Adolescent, 14 years, Darazo LGA)

“These foods make us look fine and we grow fat, so that when people see us, they feel like marrying us” (Adolescent, 13 years, Shira LGA)

“I usually like fried yam with egg, and Naman Suya [beef barbeque]”[…] We like these foods because they are very sweet [meaning tasty]” (Adolescent, 13 years, Ningi LGA).

5.5. Autonomy

“I want to marry next year, so I can be independent, to cook what I want, and do everything that I want to” (Adolescent, 13 years, Darazo LGA)

“We are not usually given meat, milk, fish and eggs to eat at home. Our parents sometimes say the reason is because of the school fees that they have to pay, so they cannot afford these foods, since our families are large” (Adolescent, 13 years, Tafawa Balewa LGA)

“Me, I don’t want to marry early, because I want to go to [secondary] school and be educated. I don’t want to marry at less than 20 years” (Adolescent, 15 years, Darazo LGA)

5.6. Gender Disparities in Household Access to Food

“No. Usually boys have larger portions than girls in the house. The reason is because of their nature and their body size. Another reason is that they do a lot of heavy work, so they eat a lot” (Adolescent, 13 years, Darazo LGA)

“The quantity given to girls and boys is not the same. Haba! Su fa maza ne [they are boys]!” (Adolescent, 13 years, Gamawa LGA)

“Boys’ and our fathers’ food at home is bigger than ours because they said they need more energy than we do. Because of the nature of their bodies and the nature of the jobs that they do. They usually go to the farm, market, and other social meetings. Also, they need strength to make babies and impregnate us” (Adolescent, 12 years, Shira LGA)

“Yes, both boys and girls are given the same share of animal foods” (Adolescent, 14 years, Darazo LGA)

“The portions of animal foods that girls receive is not equal to that of boys” (Adolescent, 11 years, Alkaleri LGA)

5.7. Marriage and Courtship Practices in the Community

“At 14–17, if you have passed that age, nobody will marry you” (Adolescent, 12 years, Shira LGA)

“From 15 to 20 years. Nowadays, we prefer to marry when we finish secondary school after we have learned to read and write” (Adolescent, 16 years, Tafawa Balewa LGA)

“At 14–16 years, when we finish our [primary] school. If you have passed that age, people will say, you are a bad person, that is why no one wants to marry you” (Adolescent, 11 years, Ningi LGA)

“My wedding is coming up after the [Muslim] fasting. My husband-to-be is the one that gave me meat yesterday” (Adolescent, 14 years, Gamawa LGA)

“It’s only if our boyfriends come for “hira” [evening discussion] that they will bring suya [beef barbeque]” (Adolescent, 14 years, Gamawa LGA)

“My boyfriend usually brings suya for me, that is why I love him” (Adolescent,13 years, Ningi LGA)

“Usually, it’s once in a month when our boyfriends buy them [animal source foods] for us that we eat these foods” (Adolescent, 13 years, Shira LGA)

5.8. Agricultural Landscapes and Economic Access

“We like these foods [tuwo, groundnuts, beans, sesame] because they grow well in our community. Things like maize do not grow well, so we farm them in very small quantities” (Adolescent, 13 years, Gamawa LGA)

“Fish, eggs, and milk are not given [to us] because of lack of money” (Adolescent, 14 years, Tafawa Balewa LGA)

“The last time we ate meat was during the Muslim Festival [Eid-el Kabir, popularly referred to as Big Sallah] and since then, we have not seen meat” (Adolescent, 13 years, Alkaleri LGA)

“Our parents do not just kill animals for eating at home. They are usually for sale” (Adolescent, 14 years, Alkaleri LGA)

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- United Nations Children’s Fund. Adolescents Statistics; United Nations Children’s Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/adolescents/overview/ (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia. Adolescent Nutrition: A Review of the Situation in Selected South-East Asian Countries; WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia: New Delhi, India, 2006; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/204764 (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- Ransom, E.; Elder, L. Nutrition of Women and Adolescent Girls: Why It Matters: Population Reference Bureau. 2003. Available online: https://www.prb.org/resources/nutrition-of-women-and-adolescent-girls-why-it-matters/ (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- National Bureau of Statistics. Nigeria Multidimensional Poverty Index (2022); National Bureau of Statistics of the Federal Republic of Nigeria: Abuja, Nigeria, 2022.

- World Population Review. World Population by Country 2023. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/ (accessed on 29 September 2023).

- Adamu, A. Exposure of Hausa women to mass media messages: Health and risk perception of cultural practices affecting maternal health in rural communities of Bauchi state, Nigeria. Commun. Cult. Afr. 2020, 2, 6–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. Report on the Nutrition and Health Situation of Nigeria: National Nutrition and Health Survey; National Bureau of Statistics: Abuja, Nigeria, 2018. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/media/2181/file/Nigeria-NNHS-2018.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- Bauchi State Rural Access and Agricultural Marketing Project. Resettlement Action Plan for the Proposed Rehabilitation of the 19 Km Liman Katagum—Luda—Lekka Rural Access Road in Bauchi State. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/ar/800671571902596867/Resettlement-Action-Plan-for-the-Proposed-Rehabilitation-of-the-19-km-Liman-Katagum-Luda-Lekka-Rural-Access-Road-in-Bauchi-State.docx (accessed on 22 November 2023).

- Sarmiento, I.; Ansari, U.; Omer, K.; Gidado, Y.; Baba, M.C.; Gamawa, A.I.; Andersson, N.; Cockcroft, A. Causes of short birth interval (kunika) in Bauchi State, Nigeria: Systematizing local knowledge with fuzzy cognitive mapping. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Population Commission (NPC); ICF International. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018; National Population Commission (NPC): Abuja, Nigeria; ICF International: Rockville, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- State Accountability, Transparency, and Effectiveness Activity. Political Economy Analysis of Bauchi State. 2020; United States Agency for International Development Nigeria (USAID/Nigeria). Available online: https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00Z7DF.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2023).

- Mohammed, R.; Usman, A.B.; Abdurrahman, S.; Imam, M.G.; Muhammad, Y.A. Analysis of household vegetable consumption in Federal Low Cost Area of Bauchi Metropolis, Bauchi State, Nigeria. J. Agric. Econ. Environ. Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, T.; Amare, M.; Oyeyemi, M.; Fadare, O. Synopsis: Study of the Determinants of Chronic Malnutrition in Northern Nigeria: Qualitative Evidence from Kebbi and Bauchi States, No. 43, NSSP Policy Notes. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). Available online: https://www.canr.msu.edu/fsp/publications/research-papers/fsp%20research%20paper%2082.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- Adamu, M. The Hausa Factor in West African History; Ahmadu Bello University Press: Zaria, Nigeria, 1978; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Blum, L.S.; Swartz, H.; Olisenekwu, G.; Erhabor, I.; Gonzalez, W. Social and economic factors influencing intrahousehold food allocation and egg consumption of children in Kaduna State, Nigeria. Matern. Child Nutr. 2023, 19, e13442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.; Seabrook, J.A.; Stranges, S.; Clark, A.F.; Haines, J.; O’Connor, C.; Doherty, S.; Gilliland, J.A. Examining the correlates of adolescent food and nutrition knowledge. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, N.; Roy, S.K.; Ahmed, T.; Ahmed, A.M. Nutritional status, dietary intake, and relevant knowledge of adolescent girls in rural Bangladesh. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2010, 28, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agustina, R.; Wirawan, F.; Sadariskar, A.A.; Setianingsing, A.A.; Nadiya, K.; Prafiantini, E.; Asri, E.K.; Purwanti, T.S.; Kusyuniati, S.; Karyadi, E.; et al. Associations of knowledge, attitude, and practices toward anemia with anemia prevalence and height-for-age z-score among Indonesian adolescent girls. Food Nutr. Bull. 2021, 42, S92–S108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.S.; Chen, J.Y.; Sun, K.S.; Tsang, J.P.; Ip, P.; Lam, C.L. Adolescent knowledge, attitudes and practices of healthy eating: Findings of qualitative interviews among Hong Kong families. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiafe, M.A.; Apprey, C.; Annan, R.A. Nutrition education improves knowledge of iron and iron-rich food intake practices among young adolescents: A nonrandomized controlled trial. Int. J. Food Sci. 2023, 2023, 1804763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, A.; Heary, C.; Nixon, E.; Kelly, C. Factors influencing the food choices of Irish children and adolescents: A qualitative investigation. Health Promot. Int. 2010, 25, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, L.S.; Khan, R.; Sultana, M.; Soltana, N.; Siddiqua, Y.; Khondker, R.; Sultana, S.; Tumilowicz, A. Using a gender lens to understand eating behaviors of adolescent females living in low-income households in Bangladesh. Matern. Child Nutr. 2019, 15, e12841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, S.D.; Thompson, W.O.; Davis, H.C. Fourth-grade children’s observed consumption of, and preferences for, school lunch foods. Nutr. Res. 2000, 20, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Legarre, N.; Santaliestra-Pasías, A.M.; Beghin, L.; Dallongeville, J.; de la O, A.; Gilbert, C.; González-Gross, M.; De Henauw, S.; Kafatos, A.; Kersting, M.; et al. Dietary patterns and their relationship with the perceptions of healthy eating in European adolescents: The HELENA study. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2019, 38, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keats, E.C.; Rappaport, A.I.; Shah, S.; Oh, C.; Jain, R.; Bhutta, Z.A. The dietary intake and practices of adolescent girls in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bawajeeh, A.; Zulyniak, M.A.; Evans, C.E.; Cade, J. Characterizing Adolescents’ Dietary intake by taste: Results from the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 893643, ; Erratum in Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1046893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cermak, S.A.; Curtin, C.; Bandini, L.G. Food selectivity and sensory sensitivity in children with autism spectrum disorders. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.S.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, M.H. Eating habits and food preferences of elementary school students in urban and suburban areas of Daejeon. Clin. Nutr. Res. 2015, 4, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agofure, O.; Odjimogho, S.; Okandeji-Barry, O.; Moses, V. Dietary pattern and nutritional status of female adolescents in Amai Secondary School, Delta State, Nigeria. Pan. Afr. Med. J. 2021, 38, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Uba, D.S.; Islam, M.R.; Haque, M.I.; Chowdhury, A.A.; Shariful Islam, S.M.; Muhammad, F. Nutritional status of adolescent girls in a selected secondary school of North-Eastern Part of Nigeria. Middle East J. Rehabil. Health Stud. 2020, 7, e104331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, F.O.; Adenekan, R.A.; Adeoye, I.A.; Okekunle, A.P. Nutritional status, dietary patterns and associated factors among out-of-school adolescents in Ibadan, Nigeria. World Nutr. 2021, 12, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeroy, K.R.; Bibeau, D.; Steckler, A.; Glanz, K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 351–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twintoh, R.F.; Anku, P.J.; Amu, H.; Darteh, E.K.M.; Korsah, K.K. Childcare practices among teenage mothers in Ghana: A qualitative study using the ecological systems theory. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, E.L.; Timmer, A. Children’s and adolescents’ characteristics and interactions with the food system. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 27, 100419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanz, K.; Rimer, B.K.; Viswanath, K. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Oxfam Nigeria. Agriculture Budget Trends Analysis. 2019. Available online: https://cng-cdn.oxfam.org/nigeria.oxfam.org/s3fs-public/FinalVersion_AgricBudgetTrendsanalysis_20191126.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Mohammed, R.; Murtala, N.; Danwanka, H.A.; Haruna, U. Socio-economic characteristics influencing sugar consumption pattern in Bauchi State Nigeria. Niger. J. Agric. Agric. Technol. 2023, 3, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, S.P. Elicitation techniques for cultural domain analysis. In The Ethnographer’s Toolkit; Schensul, J., LeCompte, M., Eds.; AltaMira Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 115–151. [Google Scholar]

- Meireles, M.P.A.; de Albuquerque, U.P.; de Medeiros, P.M. What interferes with conducting free lists? A comparative ethnobotanical experiment. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2021, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.S.; Barg, F.K.; Bowles, K.H.; Alexander, M.; Goldberg, L.R.; French, B.; Kangovi, S.; Gallagher, T.R.; Paciotti, B.; Kimmel, S.E. Comparing perspectives of patients, caregivers, and clinicians on heart failure management. J. Card. Fail. 2016, 22, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keddem, S.; Barg, F.K.; Frasso, R. Practical guidance for studies using freelisting interviews. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2021, 18, E04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedenweg, K.A.; Monroe, M. Cognitive methods and a case study for assessing shared perspectives as a result of social learning. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2013, 26, 931–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.; Kaplan, R. Cognition and Environment: Functioning in an Uncertain World; Praeger: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Kearney, A.R.; Kaplan, S. Toward a methodology for the measurement of knowledge structures of ordinary people: The conceptual content cognitive map (3CM). Environ. Behav. 1997, 29, 579–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdogru, A. Analysis of the Concept of Cognitive Mapping from a Historical Perspective; Boğaziçi University: Istanbul, Turkey, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sheffel, A.; Heidkamp, R.; Mpembeni, R.; Bujari, P.; Gupta, J.; Niyeha, D.; Aung, T.; Bakengesa, V.; Msuya, J.; Munos, M.; et al. Understanding client and provider perspectives of antenatal care service quality: A qualitative multi-method study from Tanzania. J. Glob. Health 2019, 9, 011101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, J.; Mattingly, S.; Gonzalez, V.H. Perceptions, satisfactions, and performance of undergraduate students during Covid-19 emergency remote teaching. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2022, 15, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, S.; Shawa, M.; Kane, J.C.; Bwalya, B.; Sienkiewicz, M.; Kilbane, G.; Chibemba, V.; Chiluba, P.; Mtongo, N.; Metz, K.; et al. Alcohol and other drug use patterns and services in an integrated refugee settlement in Northern Zambia: A formative research study. Confl. Health 2023, 17, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahid, S.S.; Ottman, K.; Hudhud, R.; Gautam, K.; Fisher, H.L.; Kieling, C.; Mondelli, V.; Kohrt, B.A. Identifying risk factors and detection strategies for adolescent depression in diverse global settings: A Delphi consensus study. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 279, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeshita, J.; Eriksen, W.T.; Raziano, V.T.; Bocage, C.; Hur, L.; Shah, R.V.; Gelfand, J.M.; Barg, F.K. Racial differences in perceptions of psoriasis therapies: Implications for racial disparities in psoriasis treatment. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2019, 139, 1672–1679.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, M.B. The freelisting method. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Will Fly for Food. Food in Nigeria: 25 Traditional Dishes to Look Out For. Available online: https://www.willflyforfood.net/food-in-nigeria/ (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Better to Speak. Celebrating Nigerian History + Culture through Food. Available online: https://www.bettertospeak.org/stories/celebrating-nigerian-culture-through-food (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- The Washington Post. The Oily Charms of West African Cuisine. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/food/the-oily-charms-of-west-african-cuisine/2012/02/21/gIQAhBx4fR_story.html (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Smith-Morris, C. The traditional food of migrants: Meat, water, and other challenges for dietary advice. An ethnography in Guanajuato, Mexico. Appetite 2016, 105, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wencelius, J.; Garine, E.; Raimond, C. FLARES. 2017. Available online: www.anthrocogs.com/shiny/flares/ (accessed on 8 November 2023).

- Cuffia, F.; Rojas-Rivas, E.; Urbine, A.; Zaragoza-Alonso, J. Using the free listing technique to study consumers’ representations of traditional gastronomy in Argentina. J. Ethn. Food 2023, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.J.; Borgatti, S.P. Salience counts—And so does accuracy: Correcting and updating a measure for free-list-item salience. J. Linguist. Anthropol. 1997, 7, 208–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, C.; Mastrolonardo, E.; Frasso, R. Where there’s smoke, there’s fire: What current and future providers do and do not know about electronic cigarettes. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, J.; Muthukrishna, M.; Chan, K.M.; Satterfield, T. Theories of the deep: Combining salience and network analyses to produce mental model visualizations of a coastal British Columbia food web. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, M. Considerations for collecting freelists in the field: Examples from ethobotany. Field Methods 2005, 17, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, S.; Eatough, V.; Holmes, J.; Stapley, E.; Midgley, N. Framework analysis: A worked example of a study exploring young people’s experiences of depression. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2016, 13, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R; RStudio, PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2020; Available online: http://www.rstudio.com/ (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Calories in Nutri Milk Natural Apple Taste by Cway. Available online: https://www.mynetdiary.com/food/calories-in-nutri-milk-natural-apple-taste-by-cway-ml-21926152-0.html (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Fiks, A.G.; Gafen, A.; Hughes, C.C.; Hunter, K.F.; Barg, F.K. Using freelisting to understand shared decision making in ADHD: Parents’ and pediatricians’ perspectives. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011, 84, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, M.C.; Nolan, J.M.; Chen, D. An improved measure of cognitive salience in free listing tasks: A Marshallese example. Field Methods 2017, 29, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosavljevic, M.; Navalpakkam, V.; Koch, C.; Rangel, A. Relative visual saliency differences induce sizable bias in consumer choice. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Cone, J.; Moher, J. Perceptual salience influences food choices independently of health and taste preferences. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2020, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharif, I.S.; Chin, Y.; Mohd, T.M.; Mohammed, S.Z. Malaysian adolescents’ perceptions of healthy eating: A qualitative study. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 1440–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavan, C.R.; Fawzi, W.W. Addressing knowledge gaps in adolescent nutrition: Toward advancing public health and sustainable development. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, 3, nzz062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese-Masterson, A.; Murakwani, P. Assessment of adolescent girl nutrition, dietary practices and roles in Zimbabwe. Field Exch. 2016, 52, 113. Available online: www.ennonline.net/fex/52/adolescentgirlnutrition (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- Iyassu, A.; Laillou, A.; Tilahun, K.; Workneh, F.; Mogues, S.; Chitekwe, S.; Baye, K. The influence of adolescents’ nutrition knowledge and school food environment on adolescents’ dietary behaviors in urban Ethiopia: A qualitative study. Matern. Child Nutr. 2023, e13527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vio, F.; Olaya, M.; Yañez, M.; Montenegro, E. Adolescents’ perception of dietary behaviour in a public school in Chile: A focus groups study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukanu, M.M.; Delobelle, P.; Thow, A.M.; Mchiza, Z.J.-R. Determinants of dietary patterns in school going adolescents in Urban Zambia. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 956109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakabayashi, J.; Melo, G.R.; Toral, N. Transtheoretical model-based nutritional interventions in adolescents: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christiany, I.; Mu’afiro, A.; Waluyo, K.O.; Suparji, S. Nutritional intake education by peers, nutritionists, and combinations to changes in nutritional status in adolescent girl in school. Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 10, 867–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetohy, E.M.; Mahboub, S.M.; Abusalih, H.H. The effect of an educational intervention on knowledge, attitude and behavior about healthy dietary habits among adolescent females. J. High Inst. Public Health 2020, 50, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendel, J.G.; Janković, S.; Pavičić, Ž.S. The effect of nutritional and lifestyle education intervention program on nutrition knowledge, diet quality, lifestyle, and nutritional status of Croatian school children. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1019849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, G.C.B.S.; Azevedo, K.P.M.; Garcia, D.; Oliveira Segundo, V.H.; Mata, Á.N.S.; Fernandes, A.K.P.; Santos, R.P.D.; Trindade, D.D.B.B.; Moreno, I.M.; Guillén Martínez, D.; et al. Effect of School-Based Food and Nutrition Education Interventions on the Food Consumption of Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiafe, M.A.; Apprey, C.; Annan, R.A. Impact of nutrition education and counselling on nutritional status and anaemia among early adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Hum. Nutr. Metab. 2023, 31, 200182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corazza, I.; Pennucci, F.; De Rosis, S. Promoting healthy eating habits among youth according to their preferences: Indications from a discrete choice experiment in Tuscany. Health Policy 2021, 125, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Council. Girls’ Education in Nigeria Report 2014: Issues, Influencers and Actions; British Council: Abuja, Nigeria, 2014; Available online: https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/british-council-girls-education-nigeria-report.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2023).

- Baxter, S.D.; Thompson, W.O. Fourth-grade children’s consumption of fruit and vegetable items available as part of school lunches is closely related to preferences. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2002, 34, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temba, M.C.; Njobeh, P.B.; Adebo, O.A.; Olugbile, A.O.; Kayitesi, E. The role of compositing cereals with legumes to alleviate protein energy malnutrition in Africa. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council. Malnutrition and protein quality. In Quality Protein Maize; Young, V., Bier, D.M., Pellett, P.L., Eds.; National Research Council: Washington, DC, USA, 1988; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Anitha, S.; Govindaraj, M.; Kane-Potaka, J. Balanced amino acid and higher micronutrients in millets complements legumes for improved human dietary nutrition. Cereal Chem. 2019, 97, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuluwa, E.M.; Famuwagun, A.A.; Ahure, D.; Ukeyima, M.; Aluko, R.E.; Gbenyi, D.I.; Girgih, A.T. Amino acid profiles and in vitro antioxidant properties of cereal-legume flour blends. J. Food Bioact. 2021, 14, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosanya, M.E.; Freeland-Graves, J.H.; Gbemilek, A.O.; Adeosun, F.F.; Samuel, F.O.; Shokunbi, O.S. Characterization of traditional foods and diets in rural areas of Bauchi State, Nigeria: Analysis of nutrient components. Eur. J. Nutr. Food Saf. 2021, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, C.M.; Reardon, T.; Tschirley, D.; Liverpool-Tasie, S.; Awokuse, T.; Alphonce, R.; Ndyetabula, D.; Waized, B. Consumption of processed food & food away from home in big cities, small towns, and rural areas of Tanzania. Agric. Econ. 2021, 52, 749–770. [Google Scholar]

- Critchlow, N.; Newberry, L.V.J.; MacKintosh, A.M.; Hooper, L.; Thomas, C.; Vohra, J. Adolescents’ reactions to adverts for fast-food and confectionery brands that are high in fat, salt, and/or sugar (HFSS), and possible implications for future research and regulation: Findings from a cross-sectional survey of 11–19-year-olds in the United Kingdom. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1689, Erratum in Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3181. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, A.M.; Kasprzak, C.M.; Mansouri, T.H.; Gregory, A.M., II; Barich, R.A.; Hatzinger, L.A.; Leone, L.A.; Temple, J.L. An ecological perspective of food choice and eating autonomy among adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 654139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Center for Research on Women. Taking Action to Address Child Marriage: The Role of Different Sectors. Brief 6: Food Security and Nutrition. Available online: www.girlsnotbrides.org/documents/432/6.-Addressing-child-marriage-Food-Security-and-Nutrition.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Marphatia, A.A.; Ambale, G.S.; Reid, A.M. Women’s marriage age matters for public health: A review of the broader health and social implications in South Asia. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebowale, S.A.; Fagbamigbe, F.A.; Okareh, T.O.; Lawal, G.O. Survival analysis of timing of first marriage among women of reproductive age in Nigeria: Regional differences. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2012, 16, 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Csapo, M. Religious, social and economic factors hindering the education of girls in Northern Nigeria. J. Comp. Educ. 1981, 17, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izugbara, C.O.; Ezeh, A.C. Women and high fertility in Islamic northern Nigeria. J Stud. Fam. Plan. 2010, 41, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alukagberie, M.E.; Elmusharaf, K.; Ibrahim, N.; Poix, S. Factors associated with adolescent pregnancy and public health interventions to address in Nigeria: A scoping review. Reprod. Health 2023, 20, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, P.H.; Sanghvi, T.; Tran, L.M.; Afsana, K.; Mahmud, Z.; Aktar, B.; Haque, R.; Menon, P. The nutrition and health risks faced by pregnant adolescents: Insights from a cross-sectional study in Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohan, S.; Allahverdizadeh, S.; Farajzadegan, Z.; Ghojazadeh, M.; Boroumandfar, Z. Transition into the sexual and reproductive role: A qualitative exploration of Iranian married adolescent girls’ needs and experiences. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohno, A.; Techasrivichien, T.; Suguimoto, S.P.; Dahlui, M.; Nik Farid, N.D.; Nakayama, T. Investigation of the key factors that influence the girls to enter into child marriage: A meta-synthesis of qualitative evidence. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hackett, K.M.; Mukta, U.S.; Jalal, C.S.; Sellen, D.W. A qualitative study exploring perceived barriers to infant feeding and caregiving among adolescent girls and young women in rural Bangladesh. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jama, N.A.; Wilford, A.; Haskins, L.; Coutsoudis, A.; Spies, L.; Horwood, C. Autonomy and infant feeding decision-making among teenage mothers in a rural and urban setting in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efevbera, Y.; Bhabha, J.; Farmer, P.; Fink, G. Girl child marriage, socioeconomic status, and undernutrition: Evidence from 35 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, A.N.; O’Sullivan, E.J.; Kearney, J.M. Considerations for health and food choice in adolescents. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2022, 81, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Agarwal, G.G.; Singh, J.V.; Kant, S.; Singh, N. A study on consciousness of adolescent girls about their body image. Indian J. Community Med. 2011, 36, 197. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, M.; Kaur, R.; Walia, P. Exploring gender disparity in nutritional status and dietary intake of adolescents in Uttarkashi. Indian J. Hum. Dev. 2020, 14, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, C.; Lindstrom, D.; Tessema, F.; Belachew, T. Gender bias in the food insecurity experience of Ethiopian adolescents. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 66, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose, I.; Baldi, G.; Kiess, L.; Klemm, J.; Deptford, A.; de Pee, S. The difficulty of meeting recommended nutrient intakes for adolescent girls. Glob. Food Secur. 2021, 28, 100457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barugahara, E.I.; Kikafunda, J.; Gakenia, W.M. Prevalence and risk factors of nutritional anaemia among female school children in Masindi District, Western Uganda. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2013, 13, 7679–7692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeland-Graves, J.H.; Sachdev, P.K.; Binderberger, A.Z.; Sosanya, M.E. Global diversity of dietary intakes and standards for zinc, iron, and copper. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2020, 61, 126515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosdin, L.; Sharma, A.J.; Tripp, K.; Amoaful, E.F.; Mahama, A.B.; Selenje, L.; Jefferds, M.E.; Martorell, R.; Ramakrishnan, U.; Addo, O.Y. A school-based weekly iron and folic acid supplementation program effectively reduces anemia in a prospective cohort of Ghanaian adolescent girls. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 1646–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyediran, I.O.; Olajide, O.A. Assessing food security status of rural households in North Eastern Nigeria: A comparison of methodologies. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2023, 23, 22513–22533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailumo, S.S.; Folorunsho, S.T.; Amaza, P.S.; Muhammad, S. Analysis of food security and poverty status of rural farming households in Bauchi state, Nigeria. J. Agric. Res. Dev. 2016, 15, 52–65. [Google Scholar]

- Whitsett, D.; Sherman, M.F.; Kotchick, B.A. Household food insecurity in early adolescence and risk of subsequent behavior problems: Does a connection persist over time? J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2019, 44, 478–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwilo, P.C.; Olukayode, S.J.; Okolie, C.J.; Daramola, O.E.; Salami, T.J.; Uyo, I.I.; Umar, A.A. Desertification Risk Assessment of Bauchi State Using the MEDALUS Model. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352105775_Desertification_Risk_Assessment_of_Bauchi_State_using_the_MEDALUS_Model. (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- James, J.M.; Abubakar, T.; Gundiri, L.R. Impact of Deforestation on land surface temperature in Northern Part of Bauchi State, Nigeria. FUTY J. Environ. 2020, 14, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Nwokocha, A.G.; Idris, S.; Ishiaku, Y.M. Selection of Drought-Tolerant Pasture Species under Varying Soil and Moisture Conditions in Bauchi State, Nigeria. Diyala Agric. Sci. J. 2023, 15, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agedew, E.; Abebe, Z.; Ayelign, A. Exploring barriers to diversified dietary feeding habits among adolescents in the agrarian community, North West Ethiopia. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 955391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olofson, H. Cultural values, communication, and urban image in Hausaland. Urban Anthropol. 1975, 4, 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Rambo, R.A.; Bunza, D.B. Comparative Analysis of Hausa and Zarma traditional marriage culture. J. Ling Lang Cult. 2020, 6, 87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Aishah, M.R.; Alshebani, A.K.; Romdan, A.A.; Panhwar, Q.A. Using different organic wastes to improve the quality of desert soils and barley (Hordeum vulgare) plant growth. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 2022, 6, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassoun, A.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Trollman, H.; Jagtap, S.; Parra-López, C.; Cropotova, J.; Bhat, Z.; Centobelli, P.; Aït-Kaddour, A. Birth of dairy 4.0: Opportunities and challenges in adoption of fourth industrial revolution technologies in the production of milk and its derivatives. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 7, 100535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merem, E.C.; Twumasi, Y.; Wesley, J.; Olagbegi, D.; Crisler, M.; Romorno, C.; Alsarari, M.; Isokpehi, P.; Hines, A.; Hirse, G.; et al. The analysis of dairy production and milk use in Africa Using GIS. Food Public Health 2022, 12, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Rockefeller Foundation. Gender Inclusion through Clean Energy-Powered Milk Preservation in Nigeria. 2021. Available online: https://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/case-study/gender-inclusion-through-clean-energy-powered-milk-preservation-in-nigeria/ (accessed on 12 November 2023).

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | ||

| 11–12 | 22 | 45.8 |

| 13–14 | 16 | 33.4 |

| 15–16 | 10 | 20.8 |

| Education | ||

| None | 7 | 14.6 |

| Islam-based | 11 | 22.9 |

| Some primary school | 23 | 47.9 |

| Some secondary school | 7 | 14.6 |

| Preferred Foods | n | Mean Rank a | Smith’s Salience Index b | Foods Perceived to Be Nourishing | n | Mean Rank | Smith’s Salience Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pasta c | 5 | 2.60 | 0.62 | Beans | 4 | 2.25 | 0.52 |

| Rice | 4 | 2.25 | 0.57 | Rice | 3 | 2.00 | 0.44 |

| Beans | 5 | 3.20 | 0.56 | Yam | 3 | 2.33 | 0.39 |

| Tuwo d | 4 | 4.75 | 0.42 | Beef | 4 | 5.75 | 0.25 |

| Yam | 4 | 4.00 | 0.42 | Pasta | 2 | 3.00 | 0.26 |

| Egg | 4 | 5.50 | 0.34 | Egg | 3 | 5.33 | 0.23 |

| Instant noodles | 2 | 3.00 | 0.27 | Spinach | 2 | 4.00 | 0.19 |

| Beef | 3 | 4.67 | 0.21 | Oranges | 1 | 1.00 | 0.17 |

| Groundnuts | 1 | 2.00 | 0.13 | Lettuce | 1 | 1.00 | 0.17 |

| Danmalele e | 1 | 3.00 | 0.13 | Carrots | 2 | 4.50 | 0.16 |

| Danwake f | 2 | 8.50 | 0.11 | Cabbage | 1 | 2.00 | 0.14 |

| Cabbage | 1 | 6.00 | 0.10 | Tuwo c | 2 | 4.00 | 0.14 |

| Ogbono soup g | 1 | 8.00 | 0.07 | Liver | 1 | 4.00 | 0.12 |

| Potatoes | 1 | 8.00 | 0.05 | Groundnuts | 1 | 3.00 | 0.11 |

| Sesame seeds | 1 | 4.00 | 0.04 | Bread | 1 | 5.00 | 0.10 |

| Dambu h | 1 | 10.00 | 0.04 | Potatoes | 1 | 3.00 | 0.08 |

| Ice cream | 1 | 9.00 | 0.03 | Instant noodles | 1 | 5.00 | 0.08 |

| Fish | 1 | 9.00 | 0.02 | Sorrel leaves | 1 | 5.00 | 0.07 |

| Maltina | 1 | 10.00 | 0.02 | Fish | 1 | 4.00 | 0.07 |

| Margarine | 1 | 7.00 | 0.07 | ||||

| Maltina i | 2 | 8.50 | 0.05 | ||||

| Milk | 1 | 6.00 | 0.03 | ||||

| Nutrimilk j | 1 | 10.00 | 0.02 |

| Level of Influence | Emerging Themes | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Intrapersonal | Knowledge of basic concepts in nutrition |

|

| Food preferences |

| |

| Autonomy |

| |

| Interpersonal | Household food allocation |

|

| Sociocultural | Marriage and courtship practices |

|

| Environmental | Agricultural landscapes and economic access |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sosanya, M.E.; Freeland-Graves, J.H.; Gbemileke, A.O.; Adesanya, O.D.; Akinyemi, O.O.; Ojezele, S.O.; Samuel, F.O. Why Acute Undernutrition? A Qualitative Exploration of Food Preferences, Perceptions and Factors Underlying Diet in Adolescent Girls in Rural Communities in Nigeria. Nutrients 2024, 16, 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16020204

Sosanya ME, Freeland-Graves JH, Gbemileke AO, Adesanya OD, Akinyemi OO, Ojezele SO, Samuel FO. Why Acute Undernutrition? A Qualitative Exploration of Food Preferences, Perceptions and Factors Underlying Diet in Adolescent Girls in Rural Communities in Nigeria. Nutrients. 2024; 16(2):204. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16020204

Chicago/Turabian StyleSosanya, Mercy E., Jeanne H. Freeland-Graves, Ayodele O. Gbemileke, Oluwatosin D. Adesanya, Oluwaseun O. Akinyemi, Samuel O. Ojezele, and Folake O. Samuel. 2024. "Why Acute Undernutrition? A Qualitative Exploration of Food Preferences, Perceptions and Factors Underlying Diet in Adolescent Girls in Rural Communities in Nigeria" Nutrients 16, no. 2: 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16020204

APA StyleSosanya, M. E., Freeland-Graves, J. H., Gbemileke, A. O., Adesanya, O. D., Akinyemi, O. O., Ojezele, S. O., & Samuel, F. O. (2024). Why Acute Undernutrition? A Qualitative Exploration of Food Preferences, Perceptions and Factors Underlying Diet in Adolescent Girls in Rural Communities in Nigeria. Nutrients, 16(2), 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16020204