A Tritordeum-Based Diet for Female Patients with Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Effects on Abdominal Bloating and Psychological Symptoms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subject Recruitment

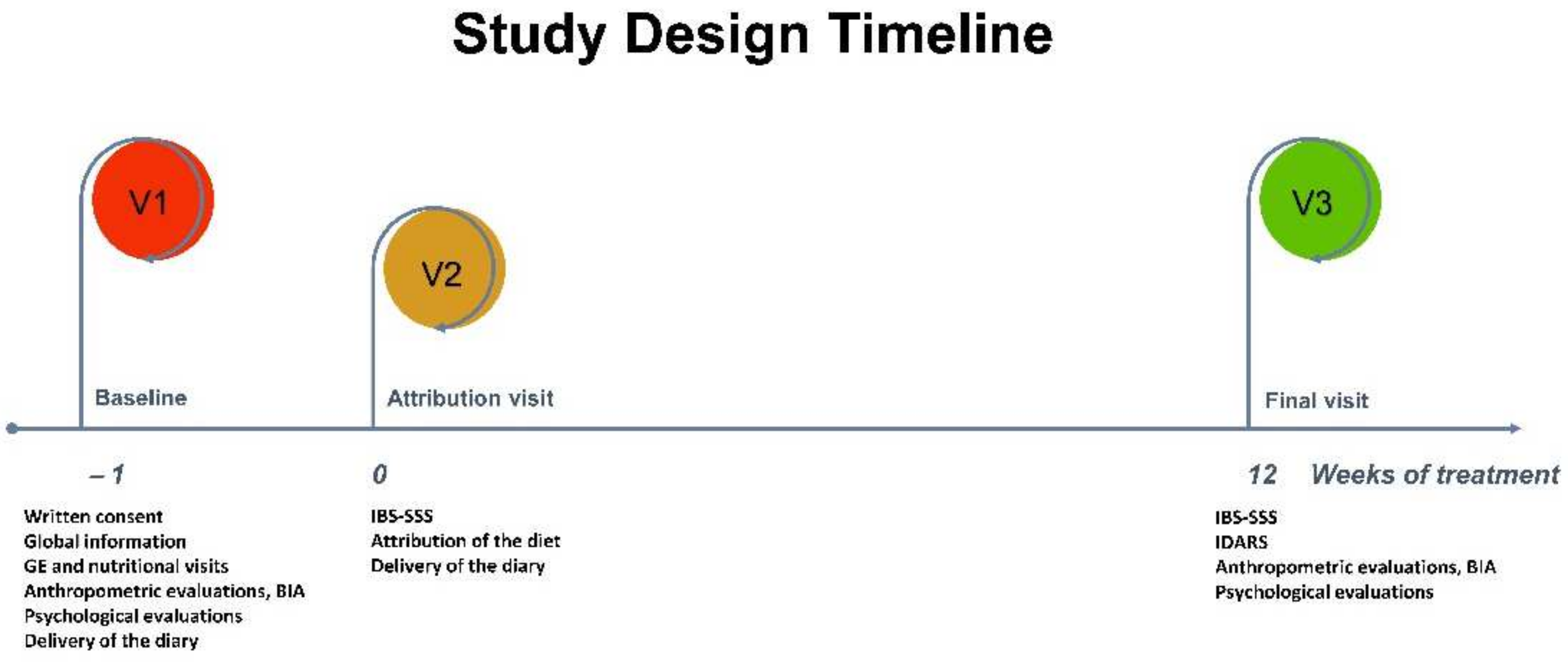

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Assessment of Anthropometric and BIA Parameters

2.4. Psychological Questionnaires

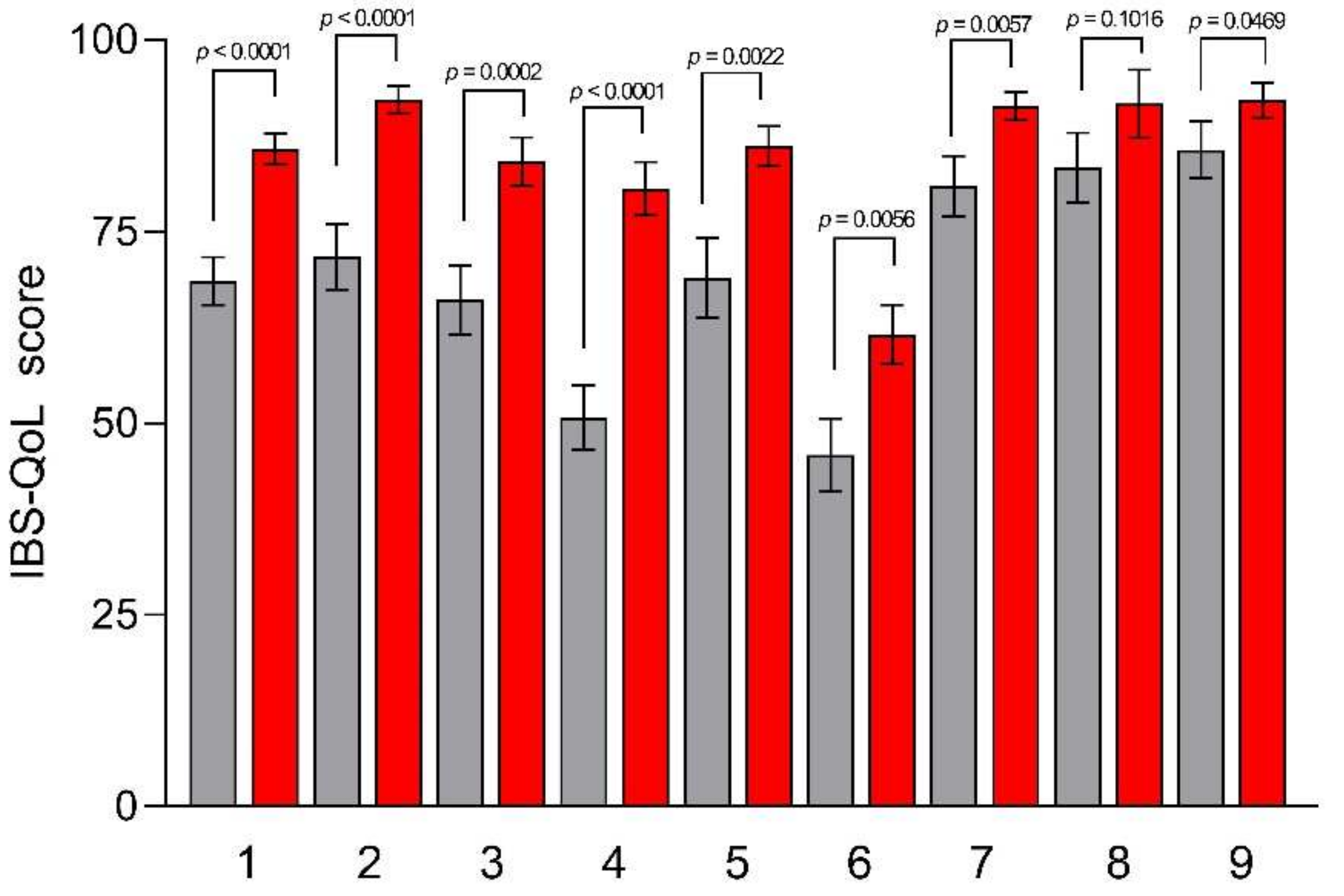

2.4.1. IBS Quality of Life Questionnaire (IBS-QoL)

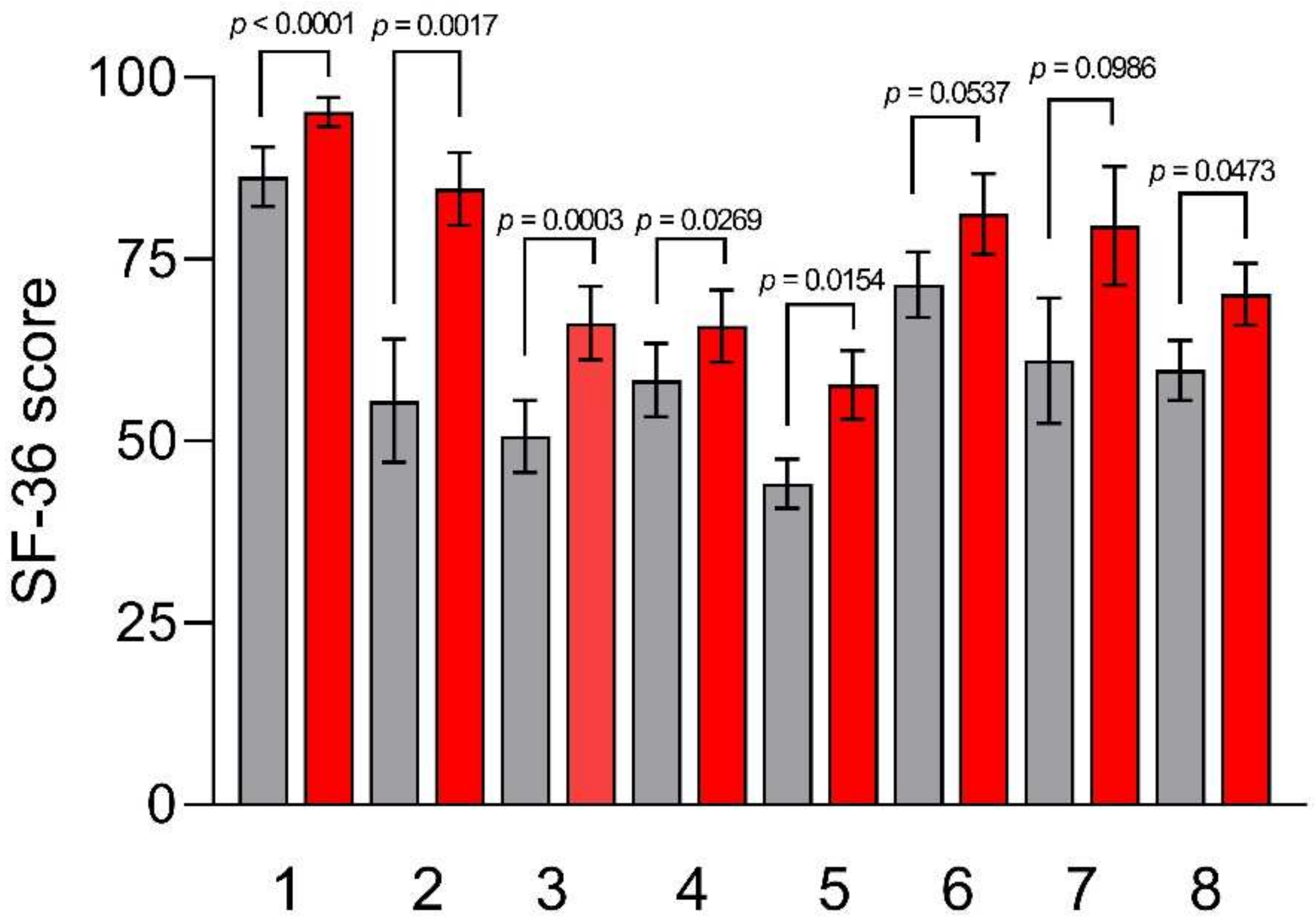

2.4.2. Thirty-Six Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36)

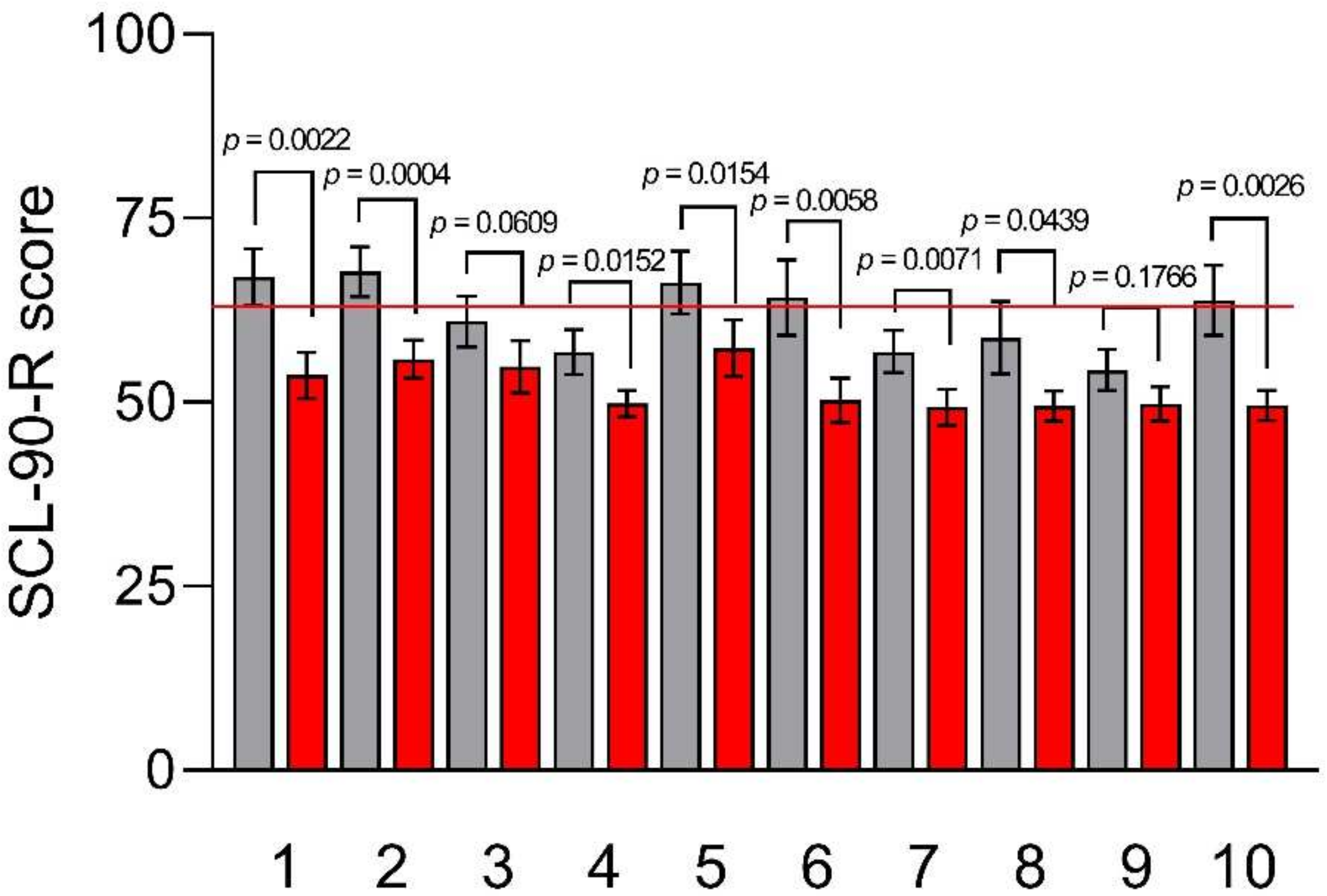

2.4.3. Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R)

2.4.4. Zung’s Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS)

2.4.5. Zung’s Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS)

2.4.6. Psychophysiological Questionnaire (QPF/R)

2.5. IBS Severity Scoring System (IBS-SSS)

2.6. Characteristics of a Tritordeum-Based Diet (TBD)

2.7. IBS Diet-Adherence Report Scale (IDARS)

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ Number and Response to Diet

3.2. Gastrointestinal (GI) Symptoms

3.3. Anthropometric and BIA Parameters

3.4. Psychological and QoL Profiles

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oka, P.; Parr, H.; Barberio, B.; Black, C.J.; Savarino, E.V.; Ford, A.C. Global prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome according to Rome III or IV criteria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 908–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.S.; Kim, N. Sex-Gender Differences in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2018, 24, 544–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, L. Irritable bowel syndrome: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, and evidence-based medicine. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 6759–6773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Videlock, E.J.; Chang, L. Latest Insights on the Pathogenesis of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 50, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buono, J.L.; Carson, R.T.; Flores, N.M. Health-related quality of life, work productivity, and indirect costs among patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2017, 15, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacy, B.E.; Cangemi, D.; Vazquez-Roque, M. Management of Chronic Abdominal Distension and Bloating. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 19, 219–231.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mari, A.; Abu Backer, F.; Mahamid, M.; Amara, H.; Carter, D.; Boltin, D.; Dickman, R. Bloating and Abdominal Distension: Clinical Approach and Management. Adv. Ther. 2019, 36, 1075–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houghton, L.A.; Whorwell, P.J. Towards a better understanding of abdominal bloating and distension in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. Off. J. Eur. Gastrointest. Motil. Soc. 2005, 17, 500–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malagelada, J.R.; Accarino, A.; Azpiroz, F. Bloating and Abdominal Distension: Old Misconceptions and Current Knowledge. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 112, 1221–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delvalle, N.M.; Dharshika, C.; Morales-Soto, W.; Fried, D.E.; Gaudette, L.; Gulbransen, B.D. Communication Between Enteric Neurons, Glia, and Nociceptors Underlies the Effects of Tachykinins on Neuroinflammation. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 6, 321–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varney, J.; Barrett, J.; Scarlata, K.; Catsos, P.; Gibson, P.R.; Muir, J.G. FODMAPs: Food composition, defining cutoff values and international application. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 32, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cozma-Petrut, A.; Loghin, F.; Miere, D.; Dumitrascu, D.L. Diet in irritable bowel syndrome: What to recommend, not what to forbid to patients! World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 3771–3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, A.; Tutino, V.; Notarnicola, M.; Riezzo, G.; Linsalata, M.; Clemente, C.; Prospero, L.; Martulli, M.; D’Attoma, B.; De Nunzio, V.; et al. Improved Symptom Profiles and Minimal Inflammation in IBS-D Patients Undergoing a Long-Term Low-FODMAP Diet: A Lipidomic Perspective. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avila, C.M.; Rodriguez-Suarez, C.; Atienza, S.G. Tritordeum: Creating a New Crop Species-The Successful Use of Plant Genetic Resources. Plants 2021, 10, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, F.; Riezzo, G.; Linsalata, M.; Orlando, A.; Tutino, V.; Prospero, L.; D’Attoma, B.; Giannelli, G. Managing Symptom Profile of IBS-D Patients with Tritordeum-Based Foods: Results From a Pilot Study. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 797192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, F.; Riezzo, G.; Orlando, A.; Linsalata, M.; D’Attoma, B.; Prospero, L.; Ignazzi, A.; Giannelli, G. A Comparison of the Low-FODMAPs Diet and a Tritordeum-Based Diet on the Gastrointestinal Symptom Profile of Patients Suffering from Irritable Bowel Syndrome-Diarrhea Variant (IBS-D): A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmulson, M.J.; Drossman, D.A. What Is New in Rome IV. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2017, 23, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulich, K.R.; Madisch, A.; Pacini, F.; Pique, J.M.; Regula, J.; Van Rensburg, C.J.; Ujszaszy, L.; Carlsson, J.; Halling, K.; Wiklund, I.K. Reliability and validity of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) and Quality of Life in Reflux and Dyspepsia (QOLRAD) questionnaire in dyspepsia: A six-country study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2008, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, M.R.; Raker, J.M.; Whelan, K. Validity and reliability of the Bristol Stool Form Scale in healthy adults and patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 44, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, C.Y.; Morris, J.; Whorwell, P.J. The irritable bowel severity scoring system: A simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1997, 11, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, S.F.; Mohktar, M.S.; Ibrahim, F. The theory and fundamentals of bioimpedance analysis in clinical status monitoring and diagnosis of diseases. Sensors 2014, 14, 10895–10928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrae, D.A.; Patrick, D.L.; Drossman, D.A.; Covington, P.S. Evaluation of the Irritable Bowel Syndrome Quality of Life (IBS-QOL) questionnaire in diarrheal-predominant irritable bowel syndrome patients. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barile, J.P.; Horner-Johnson, W.; Krahn, G.; Zack, M.; Miranda, D.; DeMichele, K.; Ford, D.; Thompson, W.W. Measurement characteristics for two health-related quality of life measures in older adults: The SF-36 and the CDC Healthy Days items. Disabil. Health J. 2016, 9, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, H.H.; Mortensen, E.L.; Lotz, M. Scl-90-R symptom profiles and outcome of short-term psychodynamic group therapy. ISRN Psychiatry 2013, 2013, 540134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zung, W.W. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics 1971, 12, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zung, W.W. A Self-Rating Depression Scale. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1965, 12, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolotti, G.; Michielin, P.; Vidotto, G.; Sanavio, E.; Bottesi, G.; Bettinardi, O.; Zotti, A.M. Metric qualities of the cognitive behavioral assessment for outcome evaluation to estimate psychological treatment effects. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015, 11, 2449–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maagaard, L.; Ankersen, D.V.; Vegh, Z.; Burisch, J.; Jensen, L.; Pedersen, N.; Munkholm, P. Follow-up of patients with functional bowel symptoms treated with a low FODMAP diet. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 4009–4019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaquero, L.; Comino, I.; Vivas, S.; Rodriguez-Martin, L.; Gimenez, M.J.; Pastor, J.; Sousa, C.; Barro, F. Tritordeum: A novel cereal for food processing with good acceptability and significant reduction in gluten immunogenic peptides in comparison with wheat. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 2201–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, R.S.; Stewart, W.F.; Liberman, J.N.; Ricci, J.A.; Zorich, N.L. Abdominal pain, bloating, and diarrhea in the United States: Prevalence and impact. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2000, 45, 1166–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Locke, G.R., 3rd; Choung, R.S.; Zinsmeister, A.R.; Schleck, C.D.; Talley, N.J. Prevalence and risk factors for abdominal bloating and visible distention: A population-based study. Gut 2008, 57, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talley, N.J.; Boyce, P.; Jones, M. Identification of distinct upper and lower gastrointestinal symptom groupings in an urban population. Gut 1998, 42, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiklund, I.K.; Fullerton, S.; Hawkey, C.J.; Jones, R.H.; Longstreth, G.F.; Mayer, E.A.; Peacock, R.A.; Wilson, I.K.; Naesdal, J. An irritable bowel syndrome-specific symptom questionnaire: Development and validation. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2003, 38, 947–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragnarsson, G.; Bodemar, G. Division of the irritable bowel syndrome into subgroups on the basis of daily recorded symptoms in two outpatients samples. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1999, 34, 993–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iovino, P.; Bucci, C.; Tremolaterra, F.; Santonicola, A.; Chiarioni, G. Bloating and functional gastro-intestinal disorders: Where are we and where are we going? World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 14407–14419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hod, K.; Ringel, Y.; van Tilburg, M.A.; Ringel-Kulka, T. Bloating in Irritable Bowel Syndrome Is Associated with Symptoms Severity, Psychological Factors, and Comorbidities. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2019, 64, 1288–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, A.Y.; Kim, N.; Oh, D.H. Abdominal bloating: Pathophysiology and treatment. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2013, 19, 433–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, T.; Negris, O.; Brown, D.; Galic, I.; Salimgaraev, R.; Zhaunova, L. Characterization of polycystic ovary syndrome among Flo app users around the world. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. RBE 2021, 19, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitkemper, M.M.; Jarrett, M.; Cain, K.C.; Shaver, J.; Walker, E.; Lewis, L. Daily gastrointestinal symptoms in women with and without a diagnosis of IBS. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1995, 40, 1511–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulak, A.; Taché, Y. Sex difference in irritable bowel syndrome: Do gonadal hormones play a role? Gastroenterol. Pol. 2010, 17, 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Heitkemper, M.M.; Chang, L. Do fluctuations in ovarian hormones affect gastrointestinal symptoms in women with irritable bowel syndrome? Gend. Med. 2009, 6 (Suppl. S2), 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasler, W.L.; Grabauskas, G.; Singh, P.; Owyang, C. Mast cell mediation of visceral sensation and permeability in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. Off. J. Eur. Gastrointest. Motil. Soc. 2022, 34, e14339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Singh, R.; Ro, S.; Ghoshal, U.C. Gut microbiota dysbiosis in functional gastrointestinal disorders: Underpinning the symptoms and pathophysiology. JGH Open Open Access J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 5, 976–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlebicz-Wojcik, A.; Slizewska, K. Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics in the Irritable Bowel Syndrome Treatment: A Review. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Xu, R.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J.; Hu, X. Probiotics, prebiotics, antibiotic, Chinese herbal medicine, and fecal microbiota transplantation in irritable bowel syndrome: Protocol for a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Medicine 2020, 99, e21502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.J.; Jarrett, M.M.; Cain, K.; Heitkemper, M. Psychological distress and GI symptoms are related to severity of bloating in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Res. Nurs. Health 2008, 31, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Lee, O.Y.; Naliboff, B.; Schmulson, M.; Mayer, E.A. Sensation of bloating and visible abdominal distension in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2001, 96, 3341–3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanazawa, M.; Miwa, H.; Nakagawa, A.; Kosako, M.; Akiho, H.; Fukudo, S. Abdominal bloating is the most bothersome symptom in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C): A large population-based Internet survey in Japan. BioPsychoSoc. Med. 2016, 10, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Oudenhove, L.; Tornblom, H.; Storsrud, S.; Tack, J.; Simren, M. Depression and Somatization Are Associated With Increased Postprandial Symptoms in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 866–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agosti, V.; Quitkin, F.M.; Stewart, J.W.; McGrath, P.J. Somatization as a predictor of medication discontinuation due to adverse events. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2002, 17, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoua, N.M.; Murray, C.D.; Winchester, W.J.; Roy, A.J.; Pitcher, M.C.; Kamm, M.A.; Emmanuel, A.V. Amitriptyline modifies the visceral hypersensitivity response to acute stress in the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 29, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanazawa, M.; Palsson, O.S.; Thiwan, S.I.; Turner, M.J.; van Tilburg, M.A.; Gangarosa, L.M.; Chitkara, D.K.; Fukudo, S.; Drossman, D.A.; Whitehead, W.E. Contributions of pain sensitivity and colonic motility to IBS symptom severity and predominant bowel habits. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 103, 2550–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, K.; Shih, W.; Videlock, E.J.; Presson, A.P.; Naliboff, B.D.; Mayer, E.A.; Chang, L. Association between early adverse life events and irritable bowel syndrome. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2012, 10, 385–390.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Items | Pre | Post | % Reduction | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severity of abdominal pain | 48.50 ± 5.30 | 23.78 ± 4.95 | −50.97 | <0.0001 |

| Abdominal pain frequency | 45.00 ± 6.58 | 19.00 ± 3.57 | −57.78 | 0.0006 |

| Severity of abdominal bloating | 63.22 ± 3.97 | 29.44 ± 4.69 | −53.43 | <0.0001 |

| Dissatisfaction with bowel habit | 67.06 ± 6.17 | 34.72 ± 4.55 | −48.22 | 0.0002 |

| Interference in life in general | 55.11 ± 5.83 | 31.11 ± 5.61 | −43.54 | <0.0001 |

| Bristol Stool Score | 4.9 (5.2–2.3) | 4.0 (5.1–2.3) | −18.37 | 0.5011 |

| Total score | 278.89 ± 18.74 | 138.06 ± 18.07 | −50.50 | <0.0001 |

| Pre | Post | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Height (m) | 1.60 ± 0.01 | // | // |

| Weight (kg) | 66.09 ± 2.45 | 62.93 ± 2.23 | 0.0002 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.04 ± 1.13 | 24.78 ± 1.06 | 0.0003 |

| Mid-upper arm circumference (cm) | 28.83 ± 0.57 | 27.93 ± 0.47 | 0.0004 |

| Shoulder circumference (cm) | 104.21 ± 1.86 | 101.32 ± 1.69 | 0.0002 |

| Abdominal circumference (cm) | 91.65 ± 2.39 | 88.39 ± 2.30 | 0.0143 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 80.23 ± 2.77 | 77.31 ± 2.51 | 0.0014 |

| Hip circumference (cm) | 100.83 ± 2.13 | 97.73 ± 1.95 | 0.0002 |

| PhA (degrees) | 5.89 ± 0.15 | 6.24 ± 0.17 | 0.0773 |

| BCM (kg) | 23.97 ± 0.68 | 24.06 ± 0.56 | 0.3713 |

| FM (kg) | 20.56 ± 1.67 | 19.14 ± 1.56 | 0.0373 |

| FFM (kg) | 45.70 ± 1.03 | 43.75 ± 0.78 | 0.0017 |

| TBW (L) | 33.35 ± 0.79 | 31.79 ± 0.59 | 0.0027 |

| ECW (L) | 15.57 ± 0.42 | 14.35 ± 0.39 | 0.0005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Riezzo, G.; Prospero, L.; Orlando, A.; Linsalata, M.; D’Attoma, B.; Ignazzi, A.; Giannelli, G.; Russo, F. A Tritordeum-Based Diet for Female Patients with Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Effects on Abdominal Bloating and Psychological Symptoms. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1361. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15061361

Riezzo G, Prospero L, Orlando A, Linsalata M, D’Attoma B, Ignazzi A, Giannelli G, Russo F. A Tritordeum-Based Diet for Female Patients with Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Effects on Abdominal Bloating and Psychological Symptoms. Nutrients. 2023; 15(6):1361. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15061361

Chicago/Turabian StyleRiezzo, Giuseppe, Laura Prospero, Antonella Orlando, Michele Linsalata, Benedetta D’Attoma, Antonia Ignazzi, Gianluigi Giannelli, and Francesco Russo. 2023. "A Tritordeum-Based Diet for Female Patients with Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Effects on Abdominal Bloating and Psychological Symptoms" Nutrients 15, no. 6: 1361. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15061361

APA StyleRiezzo, G., Prospero, L., Orlando, A., Linsalata, M., D’Attoma, B., Ignazzi, A., Giannelli, G., & Russo, F. (2023). A Tritordeum-Based Diet for Female Patients with Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Effects on Abdominal Bloating and Psychological Symptoms. Nutrients, 15(6), 1361. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15061361