Does Voluntary Family Planning Contribute to Food Security? Evidence from Ethiopia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting, Study Design, and Population

2.2. Sampling Procedures, Tools, and Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

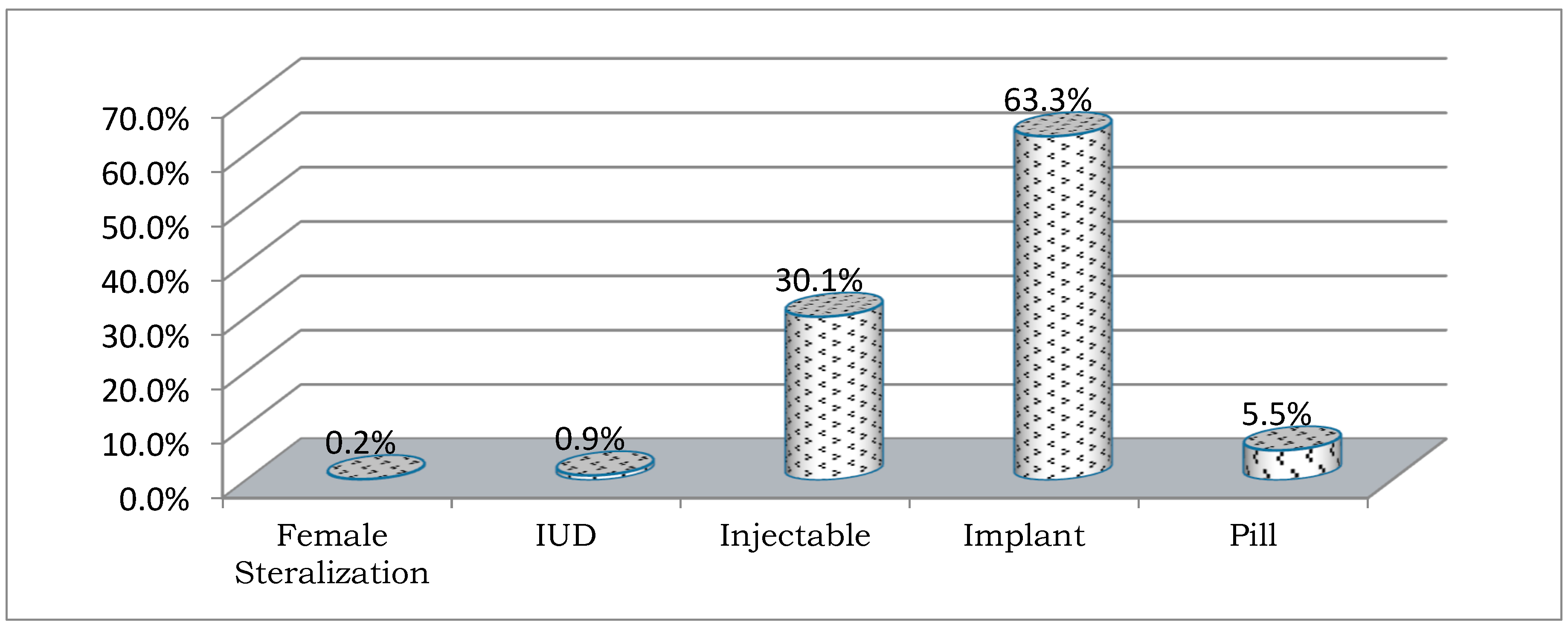

3.2. Access and Use of FP

3.3. Status of Food Access, Security, Consumption, and Availability

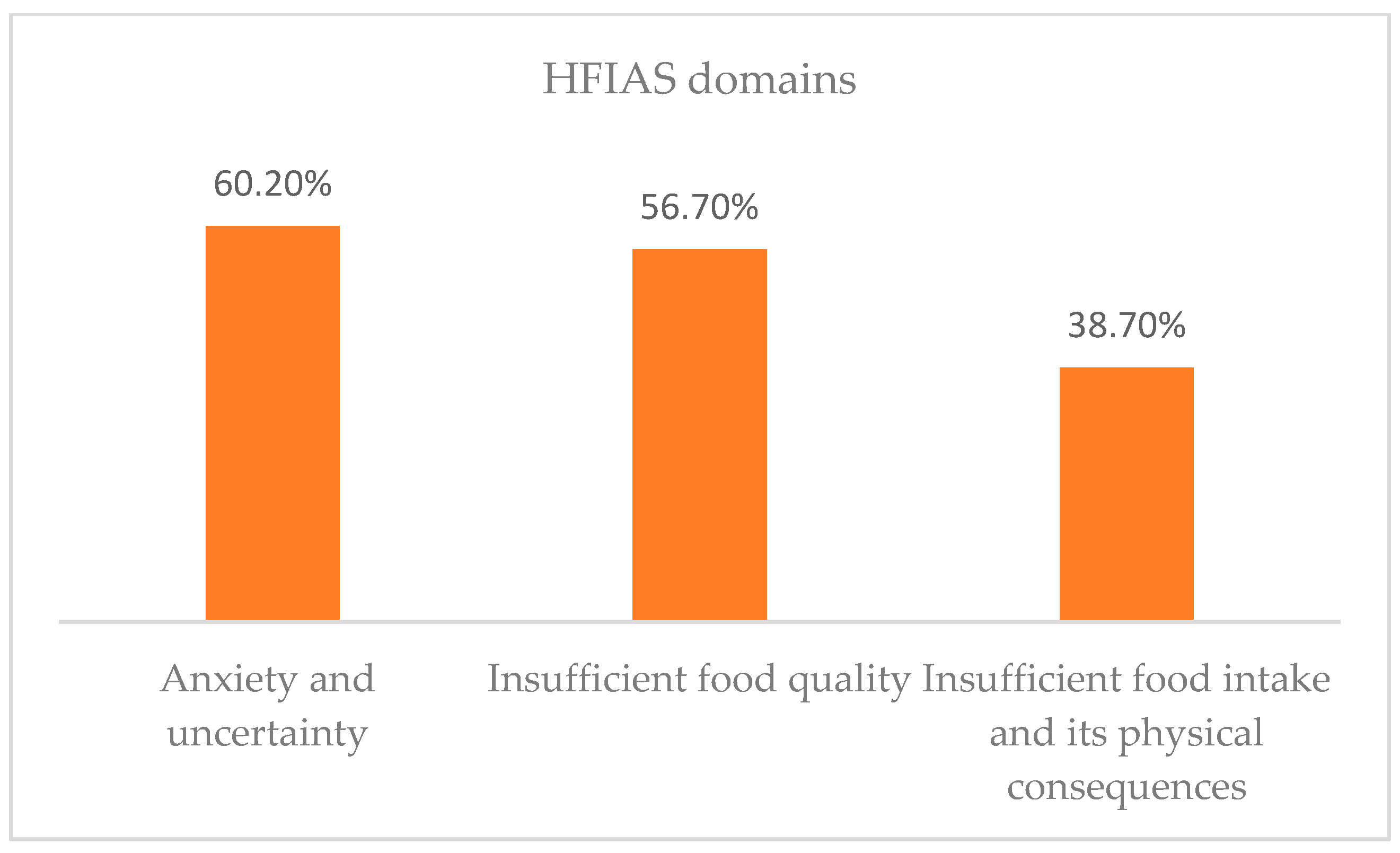

3.3.1. Food Access

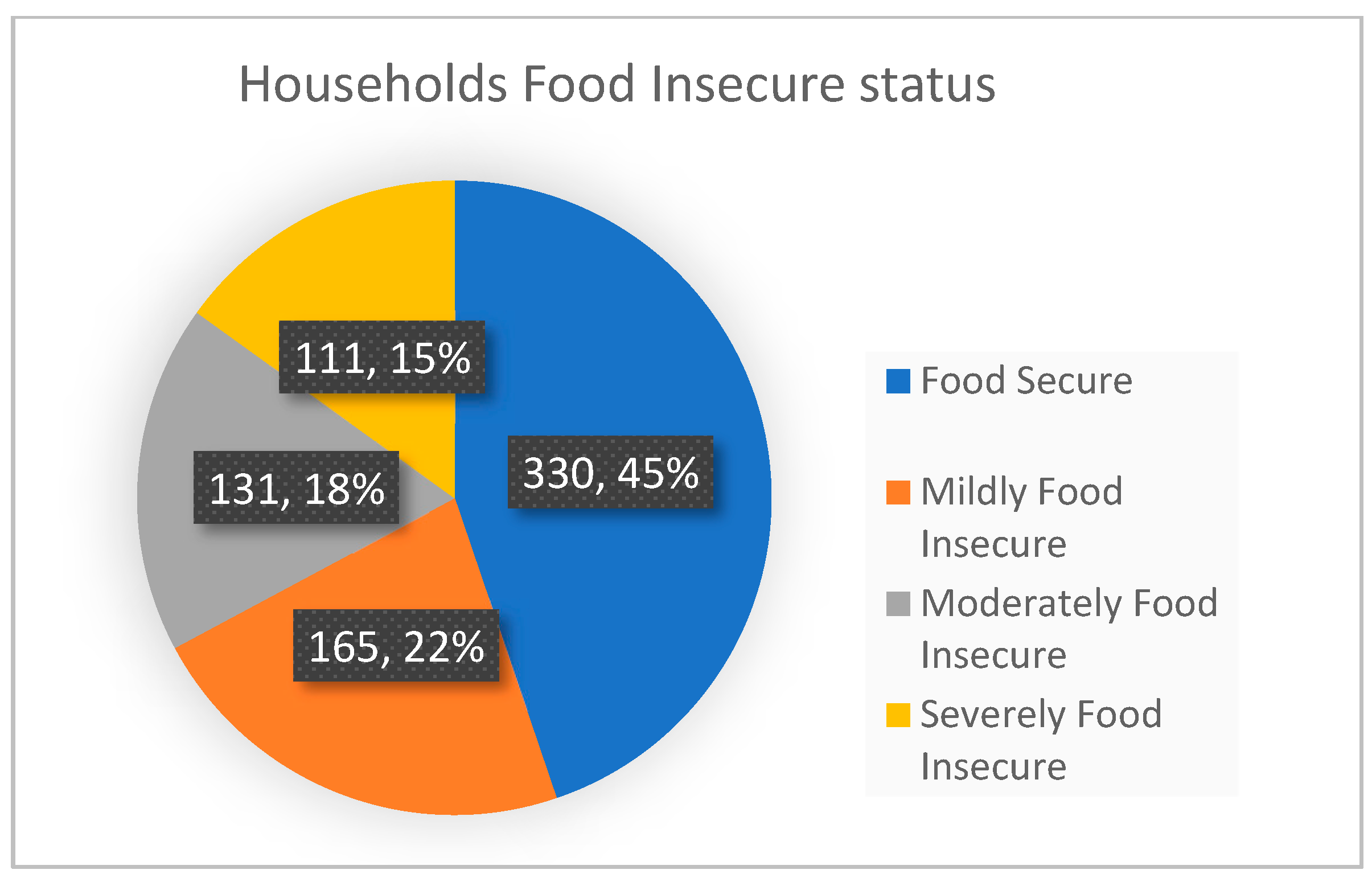

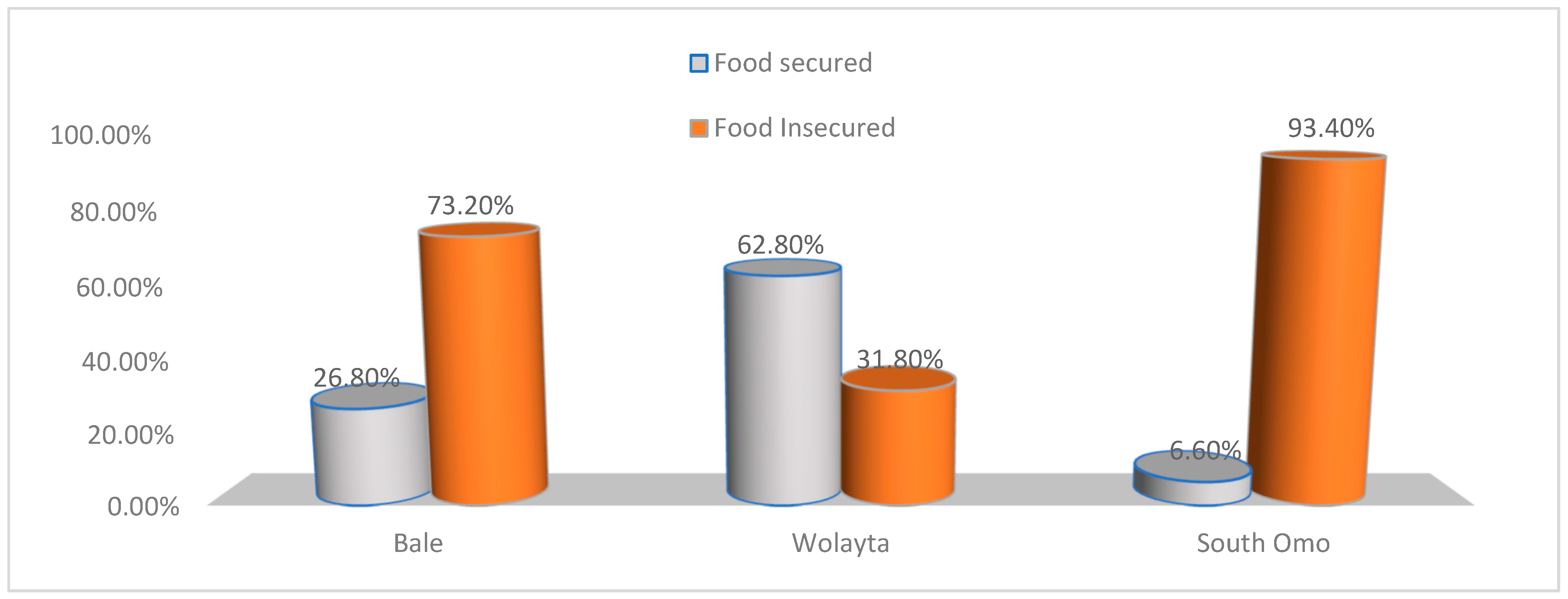

3.3.2. Food Security

3.3.3. Food Consumption

3.3.4. Food Availability

3.4. Association between FP and Food Security

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Population Council. The Rome Declaration on World Food Security. Popul. Dev. Rev. 1996, 22, 807–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2001; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture. 1996. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/w1358e/w1358e00.htm (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Bjornlund, V.; Bjornlund, H.; van Rooyen, A. Why food insecurity persists in sub-Saharan Africa: A review of existing evidence. Food Sec. 2022, 14, 845–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la O Campos, A.; Garner, E. Women’s Resilience to Food Price Volatility: A Policy Response. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome. 2014. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/i3617e/i3617e.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Adeagbo, M.O. Curbing the Menace of Food Insecurity in Nigeria’s Democratic Setting, Oyo State, Nigeria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 3, 1–9. Available online: https://www.icidr.org/ijedri_vol3no2_august2012/Curbing%20the%20Menace%20of%20Food%20Insecurity%20in%20Nigerias%20Democratic%20Setting.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Mercy Corps, What Really Matters for Resilience? Exploratory Evidence on the Determinants of Resilience to Food Security Shocks in Southern Somalia. 2013. Available online: https://www.mercycorps.org/sites/default/files/202001/WhatReallyMattersForResilienceSomaliaNov2013_0.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Kraft, J.M.; Oduyebo, T.; Jatlaoui, T.C. Dissemination and use of WHO family planning guidance and tools: A qualitative assessment. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2018, 16, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, WHO’s Family Planning Cornerstones: Safe and Effective Provision and Use of Family Planning Methods. 2010. Available online: https://www.fphandbook.org/sites/default/files/legacy/book/fph_frontmatter/whocornerstones.shtml (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Sam, A.S.; Abbas, A.; Surendran Padmaja, S.; Kaechele, H.; Kumar, R.; Müller, K. Linking Food Security with Household’s Adaptive Capacity and Drought Risk: Implications for Sustainable Rural Development. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 142, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drammeh, W.; Hamid, N.A.; Rohana, A.J. Determinants of Household Food Insecurity and Its Association with Child Malnutrition in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review of the Literature. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. 2019, 7, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, S.; Sabine, D.; Patti, K.; Wiebke, F.; Maren, R.; Ianetta, M.; Carlos, Q.F.; Mario, H.; Anthony, N.; Nicolas, N.; et al. Households and food security: Lessons from food secure households in East Africa. Agric. Food Secur. 2015, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenike, A.A. The Effect of Family Planning Methods on Food Security in Oyo State, Nigeria. J. Life Sci. 2016, 10, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götmark, F.; Andersson, M. Human fertility in relation to education, economy, religion, contraception, and family planning programs. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajao, K.; Ojofeitimi, E.; Adebayo, A.; Fatusi, A.; Afolabi, O. Influence of Family Size, Household Food Security Status, and Child Care Practices on the Nutritional Status of Under-five Children in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Afr. J. Reprod. Health/La Revue Africaine de La Santé Reproductive 2010, 14, 117–126. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41329761 (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Starbird, E.; Norton, M.; Marcus, R. Investing in Family Planning: Key to Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2016, 4, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, E.; Smith, R. Impacts of Family Planning on Food Security; Futures Group, Health Policy Project: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-59560-074-5. Available online: https://www.healthpolicyproject.com/pubs/690_RelationshipsbetweenFPandFoodSecuritFINAL.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Nutrition, Food Security and Family Planning, Multi Sectoral Nutrition Strategy 2014–2025. Available online: https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1864/Nutrition-Food-Security-and-Family-Planning-Technical-Brief-508.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Assefa, G.M.; Sherif, S.; Sluijs, J.; Kuijpers, M.; Chaka, T.; Solomon, A.; Muluneh, M.D. Gender Equality and Social Inclusion in Relation to Water, Sanitation and Hygiene in the Oromia Region of Ethiopia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dessalegn, M.; Ayele, M.; Hailu, Y.; Addisu, G.; Abebe, S.; Solomon, H.; Stulz, V. Gender inequality and the sexual and reproductive health status of young and older women in the Afar Region of Ethiopia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Driscoll, D. The Relationship between Population Growth, Age Structure, Conflict, and Governance in Sub-Saharan Africa; K4D Emerging Issues Report 38; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Policy Brief: Food Security—Issue 2, June 2006. Available online: http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/faoitaly/documents/pdf/pdf_Food_Security_Cocept_Note.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Reincke, K.; Vilvert, E.; Fasse, A.; Graef, F.; Sieber, S.; Lana, M.A. Key factors influencing food security of smallholder farmers in Tanzania and the role of cassava as a strategic crop. Food Sec. 2018, 10, 911–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USAID. Building Resilience to Recurrent Crisis: USAID Policy and Program Guidance USAID. 2012. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/building-resilience-recurrent-crisis-usaid-policy-and-program-guidance (accessed on 8 August 2021).

- Mayanja, M.N.; Morton, J.; Bugeza, J.; Rubaire, A. Livelihood profiles and adaptive capacity to manage food insecurity in pastoral communities in the central cattle corridor of Uganda. Sci. Afr. 2022, 16, e01163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recha, J.; Radeny, M.; Kimeli, P.; Atakos, V.; Kisilu, R.; Kinywee, J. Building Adaptive Capacity and Improving Food Security in Semi-Arid Eastern Kenya. CCAFS Info Note. Copenhagen, Denmark. 2016. Available online: www.ccafs.cgiar.org (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Angeles, G.; Guilkey, D.K.; Mroz, T.A. The Effects of Education and Family Planning Programs on Fertility in Indonesia 2003. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 2005, 54, 165–201. Available online: https://www.measureevaluation.org/resources/publications/wp-03-73.html (accessed on 19 August 2021). [CrossRef]

- Basin, S.; County, B.; Namenya, K.; Naburi, N.; Basin, R. Adaptive Capacity in Watershed Governance for Food Security in the Lower Adaptive Capacity in Watershed Governance for Food Security in the Lower Sio. J. Sustain. Dev. Stud. 2019, 12, 184–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Environmental Sustainability by Sociocognitive Deceleration of Population Growth. In Psychology of Sustainable Development; Schmuck, P., Schultz, W.P., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdousi, S.; Jabbar, M.; Hoque, S.; Karim, S.; Mahmood, A.; Ara, R.; Khan, N. Unmet Need of Family Planning Among Rural Women in Bangladesh. J. Dhaka Med. Coll. 2010, 19, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, C.B.; Young, J. New Lessons: The Power of Educating Adolescent Girls—A Girls Count Report on Adolescent Girls; Population Council: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, M.; Ara, G.; Rahman, A.S.; Islam, Z.; Farhad, S.; Khan, S.S.; Sanin, K.I.; Rahman, M.M.; Majoor, H.; Ahmed, T. Factors Affecting Food Security in Women Enrolled in a Program for Vulnerable Group Development. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, nzaa037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genet, E.; Abeje, G.; Ejigu, T. Determinants of unmet need for family planning among currently married women in Dangila town administration, Awi Zone, Amhara regional state; a cross sectional study. Reprod. Health 2015, 12, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfaw, S.; McCarthy, N.; Lipper, L. Climate Variability, Adaptation Strategies and Food Security in Malawi; Food and Agriculture Organization, FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3906e.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Mota, A.A.; Lachore, S.T.; Handiso, Y.H. Assessment of food insecurity and its determinants in the rural households in Damot Gale Woreda, Wolaita zone, southern Ethiopia. Agric. Food Secur. 2019, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borwankar, R.; Amieva, S. Family Planning Integration with Food Security and Nutrition. Available online: https://www.fantaproject.org/sites/default/files/resources/PRH-Family-Planning-Integration-July2015_0.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2021).

- World Food Program and CSA, Comprehensive Food Security and Vulnerability Analysis (CFSVA). 2019. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/ethiopia/ethiopia-comprehensive-food-security-and-vulnerability-analysis-cfsva-2019 (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Asesefa Kisi, M.; Tamiru, D.; Teshome, M.S.; Tamiru, M.; Feyissa, G.T. Household food insecurity and coping strategies among pensioners in Jimma Town, South West Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Cost of Hunger in Ethiopia, Implications for the Growth and Transformation of Ethiopia. The Social and Economic Impact of Child Undernutrition in Ethiopia, Summary Report. Available online: https://ephi.gov.et/images/nutrition/ethiopia%20-coha-summary-report-June-16-small.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2021).

- Nutrition, Food Security and Family Planning: Technical Guidance Brief. Available online: https://www.usaid.gov/global-health/health-areas/nutrition/technical-areas/nutrition-food-security-and-family-planning (accessed on 29 June 2021).

- Impacts of Family Planning on Nutrition and Food Security. Available online: https://www.healthpolicyproject.com/index.cfm?id=publications&get=pubID&pubID=690 (accessed on 29 June 2021).

- Mathur, A. Women and Food Security A Comparison of South Asia and Southeast Asia. South Asian Surv. 2011, 18, 181–206. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0971523113513373?icid=int.sj-abstract.similar-articles.2 (accessed on 6 July 2021). [CrossRef]

- Project IDEA: Informing Decision Makers to Act, Improving Nutrition and Food Security through Family Planning. Available online: https://www.prb.org/resources/improving-nutrition-and-food-security-through-family-planning/ (accessed on 11 September 2021).

- Improving Access to Family Planning Can Promote Food Security in a Changing Climate. 2012. Available online: https://www.measureevaluation.org/resources/publications/fs-12-71.html (accessed on 11 September 2021).

- Borwankar, R.; Amieva, S. Desk Review of Programs Integrating Family Planning with Food Security and Nutrition. Fanta III Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance. 2015. Available online: https://www.fantaproject.org/sites/default/files/resources/FANTA-PRH-FamilyPlanning-Nutrition-May2015_0.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Agidew, A.A.; Singh, K.N. Determinants of food insecurity in the rural farm households in South Wollo Zone of Ethiopia: The case of the Teleyayen sub-watershed. Agric. Econ. 2018, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyisso, M.; Belachew, T.; Tesfay, A.; Addisu, Y. Differentials of modern contraceptive methods use by food security status among married women of reproductive age in Wolaita Zone, South Ethiopia. Arch. Public Health 2015, 73, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirkuzie, A.H. Exploring inequities in skilled care at birth among migrant population in a metropolitan city Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; a qualitative study. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah Zhou, D.; Shah, T.; Ali, S.; Ahmad, W.; Din, I.U.; Ilyas, A. Factors affecting household food security in rural northern hinterland of Pakistan. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2019, 18, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Statistical Agency Population Projection (CSA2020) of Ethiopia. Available online: https://www.statsethiopia.gov.et/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Projected-Population-of-Ethiopia-20112019.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Jennifer Coates Anne Swindale Paula Bilinsky Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Food Access: Indicator Guide VERSION 3. 2007. Available online: http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/eufao-fsi4dm/doc-training/hfias.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Mini Demographic and Health Survey Ethiopian Public Health Institute. Federal Ministry of Health Addis Ababa. 2019. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR363/FR363.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Merera, A.M.; Lelisho, M.E.; Pandey, D. Prevalence and Determinants of Contraceptive Utilization among Women in the Reproductive Age Group in Ethiopia. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2021, 9, 2340–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador Castell, G.; Pérez Rodrigo, C.; de la Cruz, J.N.; Aranceta Bartrina, J. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS). 2015. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3092/309238519032.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2021).

| Sources of Information | Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family Planning Source of information | Television | 5 | 0.7 |

| Health care providers | 16 | 2.2 | |

| Health Extension Workers | 710 | 96.3 | |

| No common source | 6 | 0.8 | |

| Trusted source of information for Family Planning | Television | 5 | 0.7 |

| Health care providers | 18 | 2.5 | |

| Health Extension Workers | 706 | 95.7 | |

| No common source | 8 | 1.1 | |

| Variables (In the Past Four Weeks) | Overall | FP User | Non-User | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percent | Percent | Percent | |||

| Did you worry that your household would not have enough food? Were you or any household member not able to eat the kinds of foods you preferred because of a lack of resources? | Yes | 444 | 60.2 | 62.0 | 53.8 | 0.062 |

| Yes | 467 | 63.4 | 64.4 | 59.5 | 0.254 | |

| Did you or any household member have to eat a limited variety of foods due to a lack of resources? | Yes | 382 | 51.8 | 52.0 | 51.3 | 0.872 |

| Did you or any household member have to eat some foods that you really did not want to eat because of a lack of resources to obtain other types of food? | Yes | 292 | 39.6 | 37.3 | 48.1 | 0.014 |

| Did you or any household member have to eat a smaller meal than you felt you needed because there was not enough food? | Yes | 299 | 40.6 | 39.0 | 46.2 | 0.104 |

| Did you or any household member have to eat fewer meals in a day because there was not enough food? | Yes | 203 | 27.5 | 25.0 | 36.7 | 0.004 |

| Was there ever no food to eat of any kind in your household because of a lack of resources to get food? | Yes | 119 | 16.1 | 14.7 | 21.5 | 0.038 |

| Did you or any household member go to sleep at night hungry because there was not enough food? | Yes | 64 | 8.7 | 8.3 | 10.1 | 0.467 |

| Did you or any household member go a whole day and night without eating anything because there was not enough food? | Yes | 27 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 0.919 |

| Variables | Frequency | % | How Often Did This Happen? | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rarely | Sometimes | Often | ||||

| In the past four weeks, did you worry that your household would not have enough food? | Yes | 444 | 60.2 | 44.8 1 | 51.2 2 | 4.0 2 |

| In the past four weeks, were you or any household member not able to eat the kinds of foods you preferred because of a lack of resources? | Yes | 467 | 63.4 | 44.1 2 | 54.6 2 | 1.3 2 |

| In the past four weeks, did you or any household member have to eat a limited variety of foods due to a lack of resources? | Yes | 382 | 51.8 | 64.6 2 | 34.6 3 | 0.8 3 |

| In the past four weeks, did you or any household member have to eat some foods that you really did not want to eat because of a lack of resources to obtain other types of food? | Yes | 292 | 39.6 | 59.5 2 | 38.4 3 | 2.1 3 |

| In the past four weeks, did you or any household member have to eat a smaller meal than you felt you needed because there was not enough food? | Yes | 299 | 40.6 | 72.9 3 | 26.7 3 | 0.4 4 |

| In the past four weeks, did you or any household member have to eat fewer meals in a day because there was not enough food? | Yes | 203 | 27.5 | 86.2 3 | 13.8 3 | 0.0 4 |

| In the past four weeks, was there ever no food to eat of any kind in your household because of lack of resources to get food? | Yes | 119 | 16.1 | 90.8 4 | 9.2 4 | 0.0 4 |

| In the past four weeks, did you or any household member go to sleep at night hungry because there was not enough food? | Yes | 64 | 8.7 | 90.6 4 | 9.4 4 | 0.0 4 |

| In the past four weeks, did you or any household member go a whole day and night without eating anything because there was not enough food? | Yes | 27 | 3.7 | 88.9 4 | 11.1 4 | 0.0 4 |

| Variable | Status of Food Security | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Insecure | Food Secure | |||

| Ever used family planning | Yes | 274 (38.8%) | 326 (46.2%) | 0.071 |

| Family size (mean used as cut-off) | ≤6 | 133 (18.0%) | 224 (30.4%) | 0.000 |

| >6 | 197 (26.7%) | 183 (24.8%) | ||

| Currently using family planning | Yes | 244 (33.1%) | 335 (45.5%) | 0.007 |

| Types of Food | Weight | Average Food Consumption Per Week (in Days) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Bale | Wolaita | South Omo | ||

| Main staples Pulses | 2 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 4 |

| 3 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 4 | |

| Vegetables and leaves | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Fruits | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Meat/Beef, goat, poultry, eggs, and fish | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Milk yogurt and other diaries | 4 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 7 |

| Sugar and sugar products | 0.5 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 1 |

| Oils, fat, and butter | 0.5 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 2 |

| FCS rating | 37.5 | 76 | 24 | 69.5 | |

| Category | Acceptable | Borderline food consumption | Acceptable | ||

| Variables | Crude Odd Ratio (COR) (95% CI) | Adjusted Odd Ratio (AOR) (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model I | Model II | Model III | ||

| Age | ||||

| 15–19 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 20–29 | 0.42 (0.21–0.85) | 0.20 (0.05–0.89) | 0.18 (0.04–0.83) | |

| 30–49 | 0.18 (0.09–0.36) | 0.09 (0.02–0.39) | 0.08 (0.02–0.35) | |

| Family members | ||||

| ≤ 6 | 1 | 1 | ||

| > 6 | 0.55 (0.41–0.74) | 1.05 (0.64–1.72) | ||

| Current working Status | ||||

| Working | 2.19 (1.55–3.12) | 0.59 (0.34–1.05) | ||

| Not-working | 1 | 1 | ||

| Currently using family planning | ||||

| Yes | 1.61 (1.01–3.11) | 2.01 (1.12–2.32) | 1.17 (0.05–1.89) | |

| No | 1 | |||

| Family planning used | ||||

| ≤21 months | 0.43 (0.29–0.64) | 0.53 (0.35–0.81) | 0.64 (0.42–0.99) | |

| >22 months | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Adaptive Capacity (households’ own scoring) | ||||

| Excellent | 2.82 (1.46–5.46) | 3.08 (1.19–7.96) | 2.13 (0.93–4.85) | |

| Very good | 1.58 (1.03–2.45) | 2.00 (1.04–3.85) | 1.56 (0.85–2.85) | |

| Good | 5.06 (3.45–7.43) | 3.91 (2.25–6.79) | 3.60 (2.07–6.26) | |

| Poor | 1 | 1 | ||

| Distance of health facility | ||||

| Less than or equal to 10 Kilometre | 0.66 (0.39–1.12) | 0.75 (0.43–1.32) | ||

| Greater than 10 Kilometre | 1 | 1 | ||

| Future support FP use | ||||

| Yes | 0.74 (0.43–1.25) | 0.77 (0.43–1.37) | ||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Decision-maker for FP utilization | ||||

| Myself | 1 | 1 | ||

| My husband | 0.73 (0.53–1.00) | 0.71 (0.50–1.00) | ||

| Close relatives | 0.78 (0.34–1.87) | 0.72 (0.29–1.76) | ||

| Influenced by significant others | ||||

| Yes | 0.44 (0.32–0.59) | 0.45 (0.33–0.62) | 0.51 (0.33–0.80) | |

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Assefa, G.M.; Muluneh, M.D.; Tsegaye, S.; Abebe, S.; Makonnen, M.; Kidane, W.; Negash, K.; Getaneh, A.; Stulz, V. Does Voluntary Family Planning Contribute to Food Security? Evidence from Ethiopia. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1081. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15051081

Assefa GM, Muluneh MD, Tsegaye S, Abebe S, Makonnen M, Kidane W, Negash K, Getaneh A, Stulz V. Does Voluntary Family Planning Contribute to Food Security? Evidence from Ethiopia. Nutrients. 2023; 15(5):1081. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15051081

Chicago/Turabian StyleAssefa, Geteneh Moges, Muluken Dessalegn Muluneh, Sentayehu Tsegaye, Sintayehu Abebe, Misrak Makonnen, Woldu Kidane, Kasahun Negash, Abebaye Getaneh, and Virginia Stulz. 2023. "Does Voluntary Family Planning Contribute to Food Security? Evidence from Ethiopia" Nutrients 15, no. 5: 1081. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15051081

APA StyleAssefa, G. M., Muluneh, M. D., Tsegaye, S., Abebe, S., Makonnen, M., Kidane, W., Negash, K., Getaneh, A., & Stulz, V. (2023). Does Voluntary Family Planning Contribute to Food Security? Evidence from Ethiopia. Nutrients, 15(5), 1081. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15051081