Stakeholder Beliefs about Alternative Proteins: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Aims of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

3. Review of Selected Papers

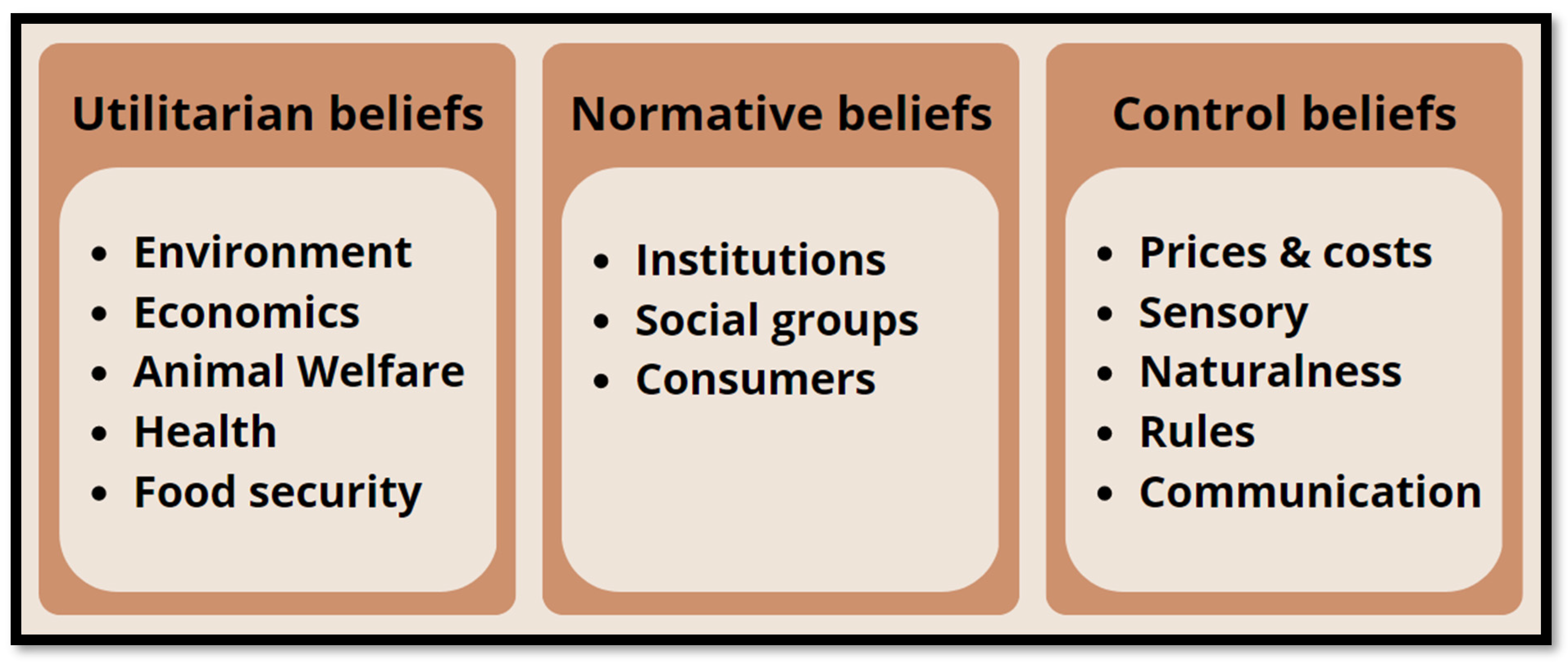

4. A Secondary Analysis of Stakeholders’ Beliefs

4.1. Utilitarian Beliefs

4.2. Normative Beliefs

4.3. Control Beliefs

“The process of producing cultured meat is largely unknown. Information on this and the reasons for it should be communicated to consumers. Especially in the development phase, when companies and researchers are in the process of organizing and starting the production process, it is important to involve consumers to close information gaps or to reduce prejudices”.[43]

5. Discussion

6. Limitations of the Study

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sexton, A.E.; Garnett, T.; Lorimer, J. Framing the future of food: The contested promises of alternative proteins. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 2019, 2, 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forum, W.E. Meat: The Future Series: Alternative Proteins; World Economic Forum: Cologny/Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lonkila, A.; Kaljonen, M. Promises of Meat and Milk Alternatives: An Integrative Literature Review on Emergent Research Themes. Agric. Hum. Values 2021, 38, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashi, Z.; McCullough, R.; Ong, L.; Ramirez, M. Alternative Proteins: The Race for Market Share Is On; McKinsey Co.: Denver, CO, USA, 2019; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Morach, B.; Witte, B.; Walker, D.; von Koeller, E.; Grosse-Holz, F.; Rogg, J.; Brigl, M.; Dehnert, N.; Obloj, P.; Koktenturk, S.; et al. Food for Thought: The Protein Transformation. Ind. Biotechnol. 2021, 17, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczebyło, A.; Halicka, E.; Rejman, K.; Kaczorowska, J. Is Eating Less Meat Possible? Exploring the Willingness to Reduce Meat Consumption among Millennials Working in Polish Cities. Foods 2022, 11, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassmann, B.; Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C. Correlates of the Willingness to Consume Insects: A Meta-Analysis. J. Insects Food Feed. 2021, 7, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Bouwman, E.P.; Reinders, M.J.; Dagevos, H. A Systematic Review on Consumer Acceptance of Alternative Proteins: Pulses, Algae, Insects, Plant-Based Meat Alternatives, and Cultured Meat. Appetite 2021, 159, 105058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, J.; Ferraro, C.; Sands, S.; Luxton, S. Alternative Protein Consumption: A Systematic Review and Future Research Directions. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 1691–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, A.; Richardson, C.D.; McSweeney, M.B. Consumer Attitudes toward Entomophagy before and after Evaluating Cricket (Acheta Domesticus)-Based Protein Powders. J. Food Sci. 2020, 85, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Barbera, F.; Verneau, F.; Amato, M.; Grunert, K. Understanding Westerners’ Disgust for the Eating of Insects: The Role of Food Neophobia and Implicit Associations. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 64, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsi, L.; Voege, L.L.; Stranieri, S. Eating Edible Insects as Sustainable Food? Exploring the Determinants of Consumer Acceptance in Germany. Food Res. Int. 2019, 125, 108573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piha, S.; Pohjanheimo, T.; Lähteenmäki-Uutela, A.; Křečková, Z.; Otterbring, T. The Effects of Consumer Knowledge on the Willingness to Buy Insect Food: An Exploratory Cross-Regional Study in Northern and Central Europe. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 70, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moons, I.; Barbarossa, C.; De Pelsmacker, P. The Determinants of the Adoption Intention of Eco-Friendly Functional Food in Different Market Segments. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 151, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, M.; Phillips, C.J.; Fielding, K.; Hornsey, M.J. Testing Potential Psychological Predictors of Attitudes towards Cultured Meat. Appetite 2019, 136, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, C.; Dillard, C. The Impact of Framing on Acceptance of Cultured Meat. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, A.C.; Luning, P.A.; Weijzen, P.; Engels, W.; Kok, F.J.; De Graaf, C. Replacement of Meat by Meat Substitutes. A Survey on Person-and Product-Related Factors in Consumer Acceptance. Appetite 2011, 56, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliner, P.; Hobden, K. Development of a Scale to Measure the Trait of Food Neophobia in Humans. Appetite 1992, 19, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicatiello, C.; De Rosa, B.; Franco, S.; Lacetera, N. Consumer Approach to Insects as Food: Barriers and Potential for Consumption in Italy. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 2271–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallen, C.; Pantin-Sohier, G.; Peyrat-Guillard, D. Cognitive Acceptance Mechanisms of Discontinuous Food Innovations: The Case of Insects in France. Rech. Appl. Mark. Engl. Ed. 2019, 34, 48–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogari, G.; Menozzi, D.; Mora, C. Sensory-liking Expectations and Perceptions of Processed and Unprocessed Insect Products. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2018, 9, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C. Impact of Sustainability Perception on Consumption of Organic Meat and Meat Substitutes. Appetite 2019, 132, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W. Profiling Consumers Who Are Ready to Adopt Insects as a Meat Substitute in a Western Society. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 39, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumpold, B.; Langen, N. Potential of Enhancing Consumer Acceptance of Edible Insects via Information. J. Insects Food Feed 2019, 5, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, A.C.; Hung, Y.; Olthof, M.R.; Verbeke, W.; Brouwer, I.A. Older Consumers’ Readiness to Accept Alternative, More Sustainable Protein Sources in the European Union. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, C.; Barnett, J. Consumer Acceptance of Cultured Meat: An Updated Review (2018–2020). Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. The Politics of Stakeholder Theory: Some Future Directions. Bus. Ethics Q. 1994, 4, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, M.B.E. A Stakeholder Framework for Analyzing and Evaluating Corporate Social Performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumin, J.; Gonçalves de Oliveira Junior, R.; Bérard, J.-B.; Picot, L. Improving Microalgae Research and Marketing in the European Atlantic Area: Analysis of Major Gaps and Barriers Limiting Sector Development. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigani, M.; Parisi, C.; Rodríguez-Cerezo, E.; Barbosa, M.J.; Sijtsma, L.; Ploeg, M.; Enzing, C. Food and Feed Products from Micro-Algae: Market Opportunities and Challenges for the EU. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 42, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paloviita, A. Developing a Matrix Framework for Protein Transition towards More Sustainable Diets. BFJ 2021, 123, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, A.E. Eating for the Post-Anthropocene: Alternative Proteins and the Biopolitics of Edibility. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2018, 43, 586–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, A.E. Food as Software: Place, Protein, and Feeding the World Silicon Valley–Style. Econ. Geogr. 2020, 96, 449–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziva, M.; Negro, S.O.; Kalfagianni, A.; Hekkert, M.P. Understanding the Protein Transition: The Rise of Plant-Based Meat Substitutes. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2020, 35, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, I.; Ferrari, A.; Woll, S. Visions of In Vitro Meat among Experts and Stakeholders. Nanoethics 2018, 12, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiles, R.M. If They Come, We Will Build It: In Vitro Meat and the Discursive Struggle over Future Agrofood Expectations. Agric. Hum. Values 2013, 30, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiles, R.M. Intertwined Ambiguities: Meat, In Vitro Meat, and the Ideological Construction of the Marketplace: Meat, In Vitro Meat, and Ideology. J. Consum. Behav. 2013, 12, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, C.; Bryant, C.J. Cultured Meat: Do Chinese Consumers Have an Appetite? Open Science Framework: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrick, T.; Gannon, S.; Kreis, K.; Zobrist, S.; Harner-Jay, C.; Goldstein, J.; Mason, S.; Olander, L.; Perez, N.; Ringler, C. Market Analysis for Cultured Proteins in Low-and Lower-Middle Income Countries; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ketelings, L.; Kremers, S.; de Boer, A. The Barriers and Drivers of a Safe Market Introduction of Cultured Meat: A Qualitative Study. Food Control 2021, 130, 108299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPartlin, M. Challenges and Prospects of Cellular Agriculture in Policy, Politics and Society. Master’s Thesis, HELDA—Digital Repository of the University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Moritz, J.; Tuomisto, H.L.; Ryynänen, T. The Transformative Innovation Potential of Cellular Agriculture: Political and Policy Stakeholders’ Perceptions of Cultured Meat in Germany. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 89, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, G.G.; Heidemann, M.S.; Borini, F.M.; Molento, C.F.M. Livestock Value Chain in Transition: Cultivated (Cell-Based) Meat and the Need for Breakthrough Capabilities. Technol. Soc. 2020, 62, 101286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievert, K.; Lawrence, M.; Parker, C.; Baker, P. What’s Really at ‘Steak’? Understanding the Global Politics of Red and Processed Meat Reduction: A Framing Analysis of Stakeholder Interviews. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 137, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woll, S.; Böhm, I. In-Vitro Meat: A Solution for Problems of Meat Production and Meat Consumption? Ernähr. Umsch. 2018, 65, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais-da-Silva, L.R.; Glufke Reis, G.; Sanctorum, H.; Forte Maiolino Molento, C. The Social Impacts of a Transition from Conventional to Cultivated and Plant-Based Meats: Evidence from Brazil. Food Policy 2022, 111, 102337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, P.; Blaustein-Rejto, D. Social and Economic Opportunities and Challenges of Plant-Based and Cultured Meat for Rural Producers in the US. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 624270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Gutiérrez, I.; Varela-Ortega, C.; Manners, R. Evaluating Animal-Based Foods and Plant-Based Alternatives Using Multi-Criteria and SWOT Analyses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specht, K.; Zoll, F.; Schümann, H.; Bela, J.; Kachel, J.; Robischon, M. How Will We Eat and Produce in the Cities of the Future? From Edible Insects to Vertical Farming—A Study on the Perception and Acceptability of New Approaches. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, D. Interpreting Qualitative Data: A Guide to the Principles of Qualitative Research, 4th ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-85702-420-6. [Google Scholar]

- La Barbera, F.; Riverso, R.; Verneau, F. Understanding Beliefs Underpinning Food Waste in the Framework of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Calitatea 2016, 17, 130. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Verneau, F.; La Barbera, F.; Kolle, S.; Amato, M.; Del Giudice, T.; Grunert, K. The Effect of Communication and Implicit Associations on Consuming Insects: An Experiment in Denmark and Italy. Appetite 2016, 106, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orkusz, A.; Wolańska, W.; Harasym, J.; Piwowar, A.; Kapelko, M. Consumers’ Attitudes Facing Entomophagy: Polish Case Perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ververis, E.; Ackerl, R.; Azzollini, D.; Colombo, P.A.; de Sesmaisons, A.; Dumas, C.; Fernandez-Dumont, A.; Ferreira da Costa, L.; Germini, A.; Goumperis, T.; et al. Novel Foods in the European Union: Scientific Requirements and Challenges of the Risk Assessment Process by the European Food Safety Authority. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Topic | References | Country | Participants | Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algae | Moons et al. [14] | Belgium | Experts in novel food markets, food companies, and health consultants (N = 10) | Workshop |

| Rumin et al. [30] | France, Spain, Portugal, UK | Scientists, private companies, non-profit institute (N = 53) | Online survey | |

| Vigani et al. [31] | UE | Experts in the agri-food sector, scientists (N = 229) | Survey and interviews | |

| Alternative proteins | Paloviita [32] | Finland | Scientists, processors, policymakers (N = 28) | Focus and interviews |

| Sexton [33] | USA | Founders, employees, and investors of private companies (N = 25) | Semi-structured interviews | |

| Sexton et al. [1] | Europe and USA | Representative of start-up and non-profit organisations (N = 12) | Semi-structured interviews | |

| Sexton [34] | USA | Entrepreneurs (N = 41) | Semi-structured interviews | |

| Tziva et al. [35] | The Netherlands | Policymakers, scientists, and NGOs members (N = 30) | Semi-structured interviews | |

| Cultured meat | Bohm et al. [36] | Germany | Scientists and entrepreneurs (N = 12) | Semi-structured interviews |

| Chiles [37] | USA | Scientists, environmentalists, retailers, policymakers, animal advocates (N = 22) | Telephone interviews | |

| Chiles [38] | USA | Scientists, environmentalists, retailers, policymakers, animal advocates (N = 22) | Semi-structured interviews | |

| Dempsey & Bryant [39] | China | Industry, investors, start-ups, and third sector representatives (N = 17) | Interviews | |

| Herrick et al. [40] | USA | Processors, food aid, and other non-profit organization members (N = 25) | Interviews | |

| Ketelings et al. [41] | UE | Legislation experts, scientists, industry representatives (N = 15) | Semi-structured interviews | |

| McPartlin [42] | Finland | Policymakers, NGOs, food tech, and research (N = 15) | Face-to-face interviews | |

| Moritz et al. [43] | Germany | Policymakers, environmental and animal welfare, NGO, scientists (N = 13) | Semi-structured interviews | |

| Reis et al. [44] | Brazil and USA | Top managers, scientists (N = 175) | Web analysis | |

| Sievert et al. [45] | Australia | Food system representatives (N = 32) | Semi-structured interviews | |

| Woll & Bohm [46] | Germany | Policymakers, animal advocates (N = 12) | Semi-structured interviews | |

| Cultured and plant-based meat | Morais-da-Silva et al. [47] | Brazil | Policymakers, private sector, scientists, non-profit organizations (N = 35) | Semi-structured interviews |

| Newton & Blaustein-Rejto [48] | USA | AP companies, NGOs, government agencies, scientists, and farmers (N = 37) | Semi-structured interviews | |

| Plant-based meat | Blanco-Gutierrez et al. [49] | Spain | Producers, food retailers, policymakers, scientists, and environmentalists (N = 63) | Face-to-face interviews |

| Insects | Specht et al. [50] | GER and USA | Scientists (N = 19) | Qualitative interviews |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amato, M.; Riverso, R.; Palmieri, R.; Verneau, F.; La Barbera, F. Stakeholder Beliefs about Alternative Proteins: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 837. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15040837

Amato M, Riverso R, Palmieri R, Verneau F, La Barbera F. Stakeholder Beliefs about Alternative Proteins: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2023; 15(4):837. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15040837

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmato, Mario, Roberta Riverso, Rossella Palmieri, Fabio Verneau, and Francesco La Barbera. 2023. "Stakeholder Beliefs about Alternative Proteins: A Systematic Review" Nutrients 15, no. 4: 837. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15040837

APA StyleAmato, M., Riverso, R., Palmieri, R., Verneau, F., & La Barbera, F. (2023). Stakeholder Beliefs about Alternative Proteins: A Systematic Review. Nutrients, 15(4), 837. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15040837