School Lunch Programs and Nutritional Education Improve Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices and Reduce the Prevalence of Anemia: A Pre-Post Intervention Study in an Indonesian Islamic Boarding School

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Intervention Methods

2.3.1. Dietary Intervention

- (a)

- 30% of RDA calories and proteins per school meal

- -

- Calories: 635–776 kcal/meal

- -

- Protein: 18–22 g/meal

- (b)

- Includes staple food, animal-/plant-derived menus, vegetables, and fruits

2.3.2. Educational Intervention

2.4. Survey Items

2.4.1. Primary Evaluation Items

- Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Test Scores

- Blood hemoglobin level

2.4.2. Secondary Evaluation Items

- Nutrition intake and nutrient adequacy ratio (NAR)

- Nutrition status items

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Review and Approval by the Ethics Review Committee

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Results

3.2. Results on the Health, Nutrition, and Hygiene Aspects of the Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Test

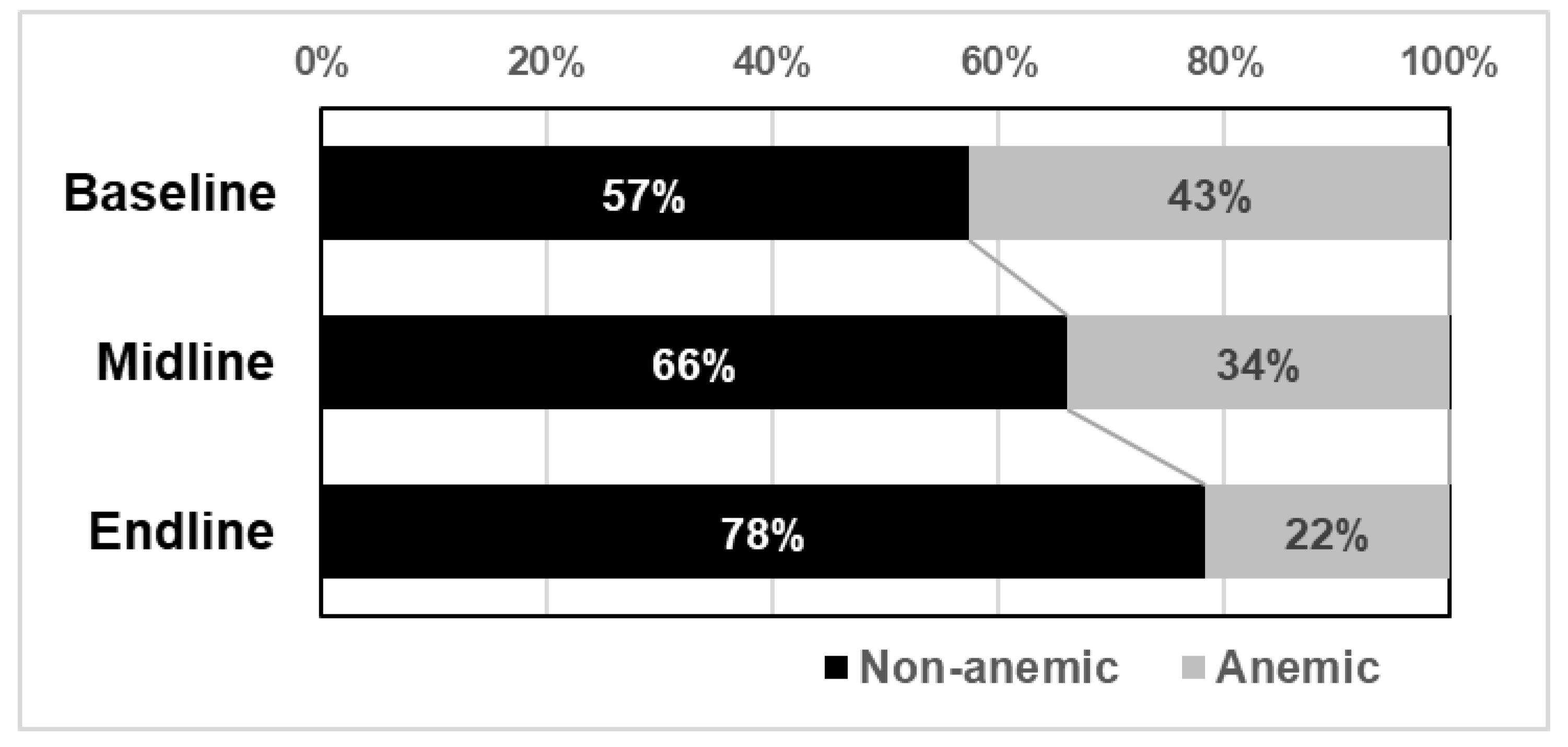

3.3. Blood Hemoglobin Levels and Anemia

3.4. Nutritional Intake

3.5. Factors Affecting Blood Hemoglobin Levels

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNICEF. Regional Report on Nutrition Security in ASEAN; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health Research and Development Republic of Indone-Sia. Basic Health Research [Internet]. National Report. Jakarta. 2013. Available online: https://www.litbang.kemkes.go.id/laporan-riset-kesehatan-dasar-riskesdas/ (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- Sekiyama, M.; Kawakami, T.; Nurdiani, R.; Roosita, K.; Rimbawan, R.; Murayama, N.; Ishida, H.; Nozue, M. School Feeding Programs in Indonesia. Jpn. J. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 76, S86–S97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiyama, M.; Roosita, K.; Ohtsuka, R. Snack foods consumption contributes to poor nutrition of rural children in West Java, Indonesia. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 21, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- WHO. Haemoglobin Concentrations for the Diagnosis of Anaemia and Assessment of Severity. Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System. [Internet]; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; pp. 1–6. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-NHD-MNM-11.1 (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- WHO. Epidemiological and Statistical Methodology Unit. Sample Size Determination: A User’s Manual [Internet]. Vol. WHO/HST/ESM/86.1; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1986; pp. 1–57. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/61764 (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia. Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia Regulation Number 75 Year 2013 on Recommended Dietary Allowances for Indonesian [Internet]; Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2013; pp. 1–10. Available online: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Home/Details/139226/permenkes-no-75-tahun-2013 (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia. Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia Regulation Number 41 Year 2014 on Balanced Nutrition Guidelines [Internet]; Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2014; pp. 1–96. Available online: http://hukor.kemkes.go.id/uploads/produk_hukum/PMK%20No.%2041%20ttg%20Pedoman%20Gizi%20Seimbang.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- Fautsch, M.Y.; Glasauer, P. Guidelines for Assessing Nutrition-Related Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices: KAP Manual [Internet]; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2014; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i3545e/i3545e.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- WHO Working Group on Growth Reference Protocol. WHO Task Force on Methods for the Natural Regu-lation of Fertility. Growth patterns of breastfed infants in seven countries. Acta Paediatr. 2000, 89, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Stewart, D.; Chang, C.; Shi, Y. Effect of a school-based nutrition educa-tion program on adolescents’ nutri-tion-related knowledge, attitudes and behaviour in rural areas of China. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2015, 20, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhao, J.; Wang, J.; Zhao, T. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of healthcare professionals toward clinically applying graduated compression stock-ings: Results of a Chinese web-based survey. J. Thromb. Thrombo-Lysis. 2019, 47, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Shinde, S.; Young, T.; Fawzi, W.W. Impacts of school feeding on educational and health outcomes of school-age children and adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Glob. Health 2021, 11, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekiyama, M.; Roosita, K.; Ohtsuka, R. Locally Sustainable School Lunch Intervention Improves Hemoglobin and Hematocrit Levels and Body Mass Index among Elementary Schoolchildren in Rural West Java, Indonesia. Nutrients 2017, 9, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adelman, S.; O Gilligan, D.; Konde-Lule, J.; Alderman, H. School Feeding Reduces Anemia Prevalence in Adolescent Girls and Other Vulnerable Household Members in a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial in Uganda. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amani, R.; Soflaei, M. Nutrition Education Alone Improves Dietary Practices but Not Hematologic Indices of Adolescent Girls in Iran. Food Nutr. Bull. 2006, 27, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total Students | Subgroup | Subgroup/ Total Students | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (%) | |

| Total | 319 | - | 115 | - | 36.1% |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 140 | 43.9% | 35 | 30.4% | 25.0% |

| Female | 179 | 56.1% | 80 | 69.6% | 44.7% |

| Grade | |||||

| 1st | 119 | 37.3% | 33 | 28.7% | 27.7% |

| 2nd | 50 | 15.7% | 15 | 13.0% | 30.0% |

| 3rd | 62 | 19.4% | 19 | 16.5% | 30.6% |

| 4th | 32 | 10.0% | 14 | 12.2% | 43.8% |

| 5th | 56 | 17.6% | 34 | 29.6% | 60.7% |

| Total Student (n = 319) | Subgroup (n = 115) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (25%, 75%) | p-Value | Median (25%, 75%) | p-Value | |||||

| Baseline | Midline | Endline | (Friedman) | Baseline | Midline | Endline | (Friedman) | |

| Knowledge | 9 (8–10) | 12 (11–13) | 12 (11–13) | <0.001 | 9 (8–10) | 12 (10–13) | 12 (11–13) | <0.001 |

| Attitude | 12 (11–13) | 14 (12–14) | 14 (13–15) | <0.001 | 12 (11–13) | 14 (12–14) | 14 (13–15) | <0.001 |

| Practice | 29 (25–33) | 37 (33–42) | 39 (34–43) | <0.001 | 29 (25–33) | 37 (32–43) | 39 (34–43) | <0.001 |

| Total Student (n = 319) | Subgroup (n = 115) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correct Response (%) | Correct Response (%) | |||||||

| Themes | Questions | Baseline | Midline | Endline | Baseline | Midline | Endline | |

| Knowledge | Clean and Healthy Lifestyle | Dressing neatly and cutting nails are not one of the clean and healthy living habits. | 92.2 | 94.7 | 94 | 88.7 | 94.8 | 93.0 |

| Drinking Water | We are recommended to drink five glasses of water every day. | 91.2 | 78.7 | 87.1 | 93.0 | 72.2 | 87.0 | |

| Breakfast | Breakfast is required as a major energy source before starting daily activities. | 2.5 | 99.7 | 97.5 | 2.6 | 72.2 | 99.1 | |

| Anemia | Anemia/lack of blood is due to not eating enough iron-rich foods. | 89 | 89.3 | 98.1 | 89.6 | 87.0 | 98.3 | |

| Vegetable Consumption | Teenagers who do not like vegetables tend to become obese in adulthood. | 55.8 | 67.4 | 76.5 | 45.2 | 61.7 | 76.5 | |

| Food Label | Food labels can provide information about the nutritional contribution of the food to our daily nutritional requirements. | 81.8 | 92.5 | 91.2 | 77.4 | 92.2 | 91.3 | |

| Salt, Sugar, and Fat | We don’t need to limit our sugar, salt, and fat consumption because they benefit our bodies. | 97.5 | 94.4 | 96.2 | 98.3 | 93.0 | 94.8 | |

| Balanced Diet | Indonesia has a balanced nutrition guide which consists of four pillars of balanced nutrition, which are: consuming diverse foods, doing physical activity, clean living habits, and weight monitoring. | 53.9 | 96.9 | 91.5 | 56.5 | 95.7 | 95.7 | |

| Pyramid of Balanced Diet | The balanced nutrition guidelines are illustrated in the form of a food pyramid; the group of foods containing carbohydrates is located at the top because we eat the most of these every day. | 31.3 | 27.3 | 42.9 | 33.9 | 24.3 | 51.3 | |

| Protein Source | Milk, eggs, chicken, meat, and beans are in the building nutrients group. | 11 | 18.2 | 14.4 | 8.7 | 86.1 | 17.4 | |

| Physical Activity | It is recommended to do physical activity or exercise at least once a week for 1 h. | 32 | 64.9 | 72.1 | 30.4 | 67.0 | 73.0 | |

| Fiber Consumption | Constipation is due to a lack of protein. | 27.3 | 38.6 | 28.8 | 31.3 | 35.7 | 31.3 | |

| Hand Washing | The right way to wash hands is using running water and soap. | 34.8 | 99.4 | 99.7 | 47.0 | 99.1 | 100.0 | |

| Adolescent Nutrition | A lack of nutrients in young women can cause malnutrition during pregnancy | 85.3 | 88.4 | 96.2 | 86.1 | 87.0 | 98.3 | |

| Surroundings Cleanness | If the surroundings are dirty and unhygienic, a person can easily contract diseases. | 84.6 | 97.8 | 91.5 | 85.2 | 97.4 | 93.9 | |

| Attitude | Clean and Healthy Lifestyle | Dressing neatly and cutting my nails have no effect on my health | 92.5 | 90.6 | 87.5 | 94.8 | 91.3 | 93.0 |

| Drinking Water | Drinking five glasses of water is enough to fulfill my requirements | 78.7 | 80.9 | 85.9 | 80.9 | 71.3 | 86.1 | |

| Breakfast | Breakfast is important to me, because otherwise I will have trouble concentrating in school | 95.3 | 97.5 | 90.9 | 93.9 | 97.4 | 92.2 | |

| Anemia | You shouldn’t worry if someone is tired, weak, lethargic, and pale | 92.5 | 92.8 | 96.2 | 90.4 | 87.8 | 95.7 | |

| Vegetable Consumption | I must consume vegetables every day to improve my digestion | 49.8 | 97.2 | 90 | 49.6 | 96.5 | 94.8 | |

| Food Label | I don’t consider nutrition and health information on food labels when choosing food | 71.2 | 85 | 84.6 | 73.0 | 85.2 | 90.4 | |

| Salt, Sugar, and Fat | I will choose foods with less sugar, salt, and fat even though these are not as tasty as foods high in sugar, salt, and fat | 76.5 | 73 | 76.2 | 75.7 | 71.3 | 80.0 | |

| Balanced Diet | I can implement the four pillars of balanced nutrition guidelines in my daily life | 80.6 | 94.7 | 94 | 80.9 | 91.3 | 94.8 | |

| Pyramid of Balanced Diet | The balanced nutrition pyramid helps me choose the right foods | 85 | 96.9 | 93.4 | 83.5 | 94.8 | 94.8 | |

| Protein Source | Eating tofu and tempeh alone is enough for building cells and tissues in our body | 50.5 | 60.2 | 60.5 | 56.5 | 60.9 | 64.3 | |

| Physical Activity | I need to do physical activity 5 times a day in a week, for at least 30 min | 64.9 | 71.5 | 81.8 | 66.1 | 74.8 | 85.2 | |

| Fiber Consumption | I need to consume vegetables and fruits to avoid constipation | 96.2 | 95.6 | 91.2 | 93.9 | 97.4 | 91.3 | |

| Hand Washing | Washing hands with running water is enough, if hands do not look dirty | 70.2 | 89 | 76.8 | 76.5 | 90.4 | 78.3 | |

| Adolescent Nutrition | I don’t need to worry about my nutritional status as a future parent now | 89 | 90 | 88.1 | 88.7 | 87.0 | 90.4 | |

| Surroundings Cleanness | I need to pay attention to the cleanliness of the surrounding environment because it will affect my health | 91.2 | 98.1 | 98.4 | 93.0 | 100.0 | 98.3 | |

| Themes | Questions | Total Student (n = 319) | Subgroup (n = 115) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (25–75%) | p-Value (Friedman) | Median (25%, 75%) | p-Value (Friedman) | ||||||

| Baseline | Midline | Endline | Baseline | Midline | Endline | ||||

| Clean and Healthy Lifestyle | How often are you neatly and cleanly dressed? | 4 (3–4) | 4 (4–4) | 4 (4–4) | 0.066 | 4 (4–4) | 4 (4–4) | 4 (4–4) | <0.05 |

| Drinking Water | How often do you drink eight glasses of water per day? | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | <0.05 | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | 0.186 |

| Breakfast | How often do you have breakfast before 9 o’clock? | 4 (3–4) | 4 (3–4) | 4 (3–4) | <0.05 | 4 (3–4) | 4 (3–4) | 4 (3–4) | 0.237 |

| Anemia | How often do you consume a source of iron (red meat, chicken liver, iron tablets)? | 1 (0–1) | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) | 0.063 | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) | <0.05 |

| Vegetable Consumption | How often do you eat vegetables? | 3 (2–4) | 4 (3–4) | 3 (3–4) | <0.05 | 3 (2–4) | 4 (2–4) | 3 (3–4) | <0.05 |

| Food Label | Did you read the food label before deciding to buy packaged food? | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (1–2) | <0.05 | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) | <0.05 |

| Salt, Sugar, and Fat | How often do you drink sweet drinks? | 2 (1–2) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (1–3) | 0.460 | 2 (1–3) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (1–3) | <0.05 |

| Balanced Diet | How often do you weigh yourself? | 0 (0–1) | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) | <0.05 | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) | <0.05 |

| Pyramid of Balanced Diet | How often do you use the balanced food pyramid as a food guide? | 0 (0–1) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–4) | <0.05 | 1 (1–1) | 2 (1–3) | 3 (1–4) | <0.05 |

| Protein Sauce | How often do you consume sources of animal protein? (eggs, red meat, chicken) | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | <0.05 | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | <0.05 |

| Physical Activity | How often do you do physical activity continuously for at least 30 min? | 2 (1–2) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | <0.05 | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | <0.05 |

| Fiber Consumption | How often do you eat fruit? | 1 (1–2) | 3 (3–4) | 4 (3–4) | <0.05 | 1 (1–2) | 4 (3–4) | 4 (3–4) | <0.05 |

| Hand Washing | Did you wash your hands after using the bathroom? | 3 (2–4) | 4 (2–4) | 4 (2–4) | <0.05 | 3 (2–4) | 4 (2–4) | 4 (3–4) | 0.605 |

| Adolescent Nutrition | How often do you seek nutrition and health information? | 1 (0–1) | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) | 0.736 | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–3) | <0.05 |

| Surroundings Cleanness | Do you help to clean up your neighborhood? | 4 (3–4) | 4 (3–4) | 4 (3–4) | <0.05 | 4 (3–4) | 4 (3–4) | 4 (3–4) | 0.251 |

| Themes | Questions | Total Student (n = 319) | Subgroup (n = 115) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improved | Not Improved | Improved | Not Improved | ||||||

| % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | ||

| Clean and Healthy Lifestyle | How often are you neatly and cleanly dressed? | 9.4% | 30 | 69.9% | 223 | 14.8% | 17 | 82.6% | 95 |

| Drinking Water | How often do you drink eight glasses of water per day? | 10.7% | 34 | 66.1% | 211 | 29.6% | 34 | 66.1% | 76 |

| Breakfast | How often do you have breakfast before 9 o’clock? | 5.0% | 16 | 84.0% | 268 | 14.8% | 17 | 83.5% | 96 |

| Anemia | How often do you consume a source of iron (red meat, chicken liver, iron tablets)? | 18.2% | 58 | 42.3% | 135 | 59.1% | 68 | 32.2% | 37 |

| Vegetable Consumption | How often do you eat vegetables? | 12.9% | 41 | 58.9% | 188 | 38.3% | 44 | 55.7% | 64 |

| Food Label | Did you read the food label before deciding to buy packaged food? | 15.4% | 49 | 51.4% | 164 | 43.5% | 50 | 49.6% | 57 |

| Salt, Sugar, and Fat | How often do you drink sweet drinks? | 10.7% | 34 | 66.1% | 211 | 14.8% | 17 | 82.6% | 95 |

| Balanced Diet | How often do you weigh yourself? | 14.1% | 45 | 54.9% | 175 | 33.9% | 39 | 60.9% | 70 |

| Pyramid of Balanced Diet | How often do you use the balanced food pyramid as a food guide? | 23.8% | 76 | 23.5% | 75 | 67.0% | 77 | 22.6% | 26 |

| Protein Sauce | How often do you consume sources of animal protein? (eggs, red meat, chicken) | 18.5% | 59 | 41.1% | 131 | 53.0% | 61 | 39.1% | 45 |

| Physical Activity | How often do you do physical activity continuously for at least 30 min? | 14.1% | 45 | 55.2% | 176 | 37.4% | 43 | 56.5% | 65 |

| Fiber Consumption | How often do you eat fruit? | 27.0% | 86 | 13.8% | 44 | 77.4% | 89 | 11.3% | 13 |

| Hand Washing | Did you wash your hands after using the bathroom? | 9.4% | 30 | 69.6% | 222 | 26.1% | 30 | 70.4% | 81 |

| Adolescent Nutrition | How often do you seek nutrition and health information? | 21.0% | 67 | 33.2% | 106 | 67.0% | 77 | 23.5% | 27 |

| Surroundings Cleanness | Do you help to clean up your neighborhood? | 8.5% | 27 | 73.4% | 234 | 18.3% | 21 | 79.1% | 91 |

| Subgroup (n = 115) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (25–75 Percentile) | p-Value | |||

| Baseline | Midline | Endline | (Friedman) | |

| Hb concentration | 12.5 (11.1–14.0) | 12.6 (11.5–13.4) | 13.1 (12.2–14.2) | <0.005 |

| Lunch | Daily | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrients | Baseline | Midline | Endline | p-Value (Friedman) | Baseline | Midline | Endline | p-Value (Friedman) |

| Energy (kcal) | 239 ± 171 | 387 ± 136 | 434 ± 137.8 | <0.05 | 1486 ± 720 | 1505 ± 498 | 1632 ± 489 | 0.12 |

| Proteins (g) | 7.5 ± 6.2 | 11.8 ± 5.5 | 11.1 ± 4.7 | <0.05 | 19.0 ± 11 | 35.6 ± 14.3 | 36.3 ± 14.3 | <0.05 |

| Fat (g) | 6.6 ± 7.8 | 12.1 ± 5.3 | 16.0 ± 5.9 | <0.05 | 13.4 ± 8.6 | 21.8 ± 9.7 | 22 ± 11.2 | <0.05 |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 37.8 ± 27.7 | 58.0 ± 24.4 | 62.0 ± 23.7 | <0.05 | 219.8 ± 105.4 | 226.9 ± 77.2 | 238.2 ± 71.6 | 0.26 |

| Iron (mg) | 1.0 ± 0.9 | 2.1 ± 1. | 2.7 ± 1.3 | <0.05 | 2.7 ± 1 | 6.9 ± 0.9 | 7.0 ± 1.0 | <0.05 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 3.4 ± 4.3 | 30.9 ± 28.1 | 17.6 ± 15.0 | <0.05 | 26.22 ± 39.4 | 55.8 ± 54.4 | 40.8 ± 44.1 | <0.05 |

| Median (25–75 Percentile) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrients | Baseline | Midline | Endline | p-Value (Friedman) |

| Energy | 44.2 (27.3–58.4) | 61.7 (52.9–74.9) | 68.5 (55.6–85.9) | <0.05 |

| Proteins | 45.1 (28.8–67.0) | 65.5 (52.9–80.6) | 59.1 (44.5–72.5) | <0.05 |

| Fat | 33.3 (48.3–60.4) | 63.8 (43.5–75.8) | 76.5 (60.4–93.2) | <0.05 |

| Carbohydrates | 43.7 (27.9–69.1) | 67.0 (54.1–87.8) | 71.3 (56.0–91.0) | <0.05 |

| Fe | 14.6 (8.0–24.0) | 30.9 (19.9–35.0) | 38.3 (26.7–45.9) | <0.05 |

| Subgroup (n = 115) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (25–75 Percentile) | p-Value | |||

| Baseline | Midline | Endline | (Friedman) | |

| BAZ | −0.09 (−0.7–0.8) | 0.04 (−0.7–0.94) | −0.08 (−0.79–0.92) | 0.607 |

| Variable | β Coef | p-Value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||

| Delta Nutrient Adequacy during Lunch | ||||

| Energy | 5.292 | 0.04 | 0.054 | 2.261 |

| Proteins | −0.642 | 0.132 | −0.258 | 0.035 |

| Fat | −2.774 | 0.03 | −0.666 | −0.034 |

| Carbohydrates | −3.808 | 0.036 | −1.275 | −0.044 |

| Iron | 0.334 | 0.009 | 0.021 | 0.143 |

| Vitamin C | −0.21 | 0.032 | −0.028 | −0.001 |

| Delta Score KAP | ||||

| Knowledge | 0.221 | 0.039 | 0.002 | 0.055 |

| Attitude | 0.024 | 0.822 | −0.019 | 0.024 |

| Practice | −0.023 | 0.826 | −0.032 | 0.025 |

| 1. CHLB | 0.092 | 0.388 | −0.2 | 0.508 |

| 2. Drinking water | 0.034 | 0.763 | −0.262 | 0.355 |

| 3. Breakfast | −0.195 | 0.075 | −0.52 | 0.025 |

| 4. Anemia | 0.044 | 0.68 | −0.269 | 0.411 |

| 5. Vegetable consumption | −0.006 | 0.955 | −0.292 | 0.276 |

| 6. Food labels | 0.039 | 0.676 | −0.196 | 0.301 |

| 7. Sugar, salt, fat | −0.112 | 0.265 | −0.378 | 0.106 |

| 8. Balanced diet | 0.033 | 0.731 | −0.325 | 0.461 |

| 9. Pyramid of balanced diet | −0.016 | 0.883 | −0.235 | 0.202 |

| 10. Protein source consumption | 0.267 | 0.007 | 0.109 | 0.652 |

| 11. Physical activity | −0.277 | 0.005 | −0.561 | −0.107 |

| 12. Fiber consumption | 0.145 | 0.151 | −0.075 | 0.474 |

| 13. Hand washing | −0.139 | 0.191 | −0.445 | 0.091 |

| 14. Adolescent nutrition | −0.087 | 0.425 | −0.381 | 0.163 |

| 15. Environmental cleanliness | −0.062 | 0.594 | −0.429 | 0.248 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rimbawan, R.; Nurdiani, R.; Rachman, P.H.; Kawamata, Y.; Nozawa, Y. School Lunch Programs and Nutritional Education Improve Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices and Reduce the Prevalence of Anemia: A Pre-Post Intervention Study in an Indonesian Islamic Boarding School. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15041055

Rimbawan R, Nurdiani R, Rachman PH, Kawamata Y, Nozawa Y. School Lunch Programs and Nutritional Education Improve Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices and Reduce the Prevalence of Anemia: A Pre-Post Intervention Study in an Indonesian Islamic Boarding School. Nutrients. 2023; 15(4):1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15041055

Chicago/Turabian StyleRimbawan, Rimbawan, Reisi Nurdiani, Purnawati Hustina Rachman, Yuka Kawamata, and Yoshizu Nozawa. 2023. "School Lunch Programs and Nutritional Education Improve Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices and Reduce the Prevalence of Anemia: A Pre-Post Intervention Study in an Indonesian Islamic Boarding School" Nutrients 15, no. 4: 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15041055

APA StyleRimbawan, R., Nurdiani, R., Rachman, P. H., Kawamata, Y., & Nozawa, Y. (2023). School Lunch Programs and Nutritional Education Improve Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices and Reduce the Prevalence of Anemia: A Pre-Post Intervention Study in an Indonesian Islamic Boarding School. Nutrients, 15(4), 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15041055