Assessing Antecedents of Restaurant’s Brand Trust and Brand Loyalty, and Moderating Role of Food Healthiness

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Review of Literature and Hypotheses Development

2.1. DINESERV

2.2. Brand Trust and Brand Loyalty

2.3. Relationship between Attributes of DINSERV, Brand Trust and Brand Loyalty

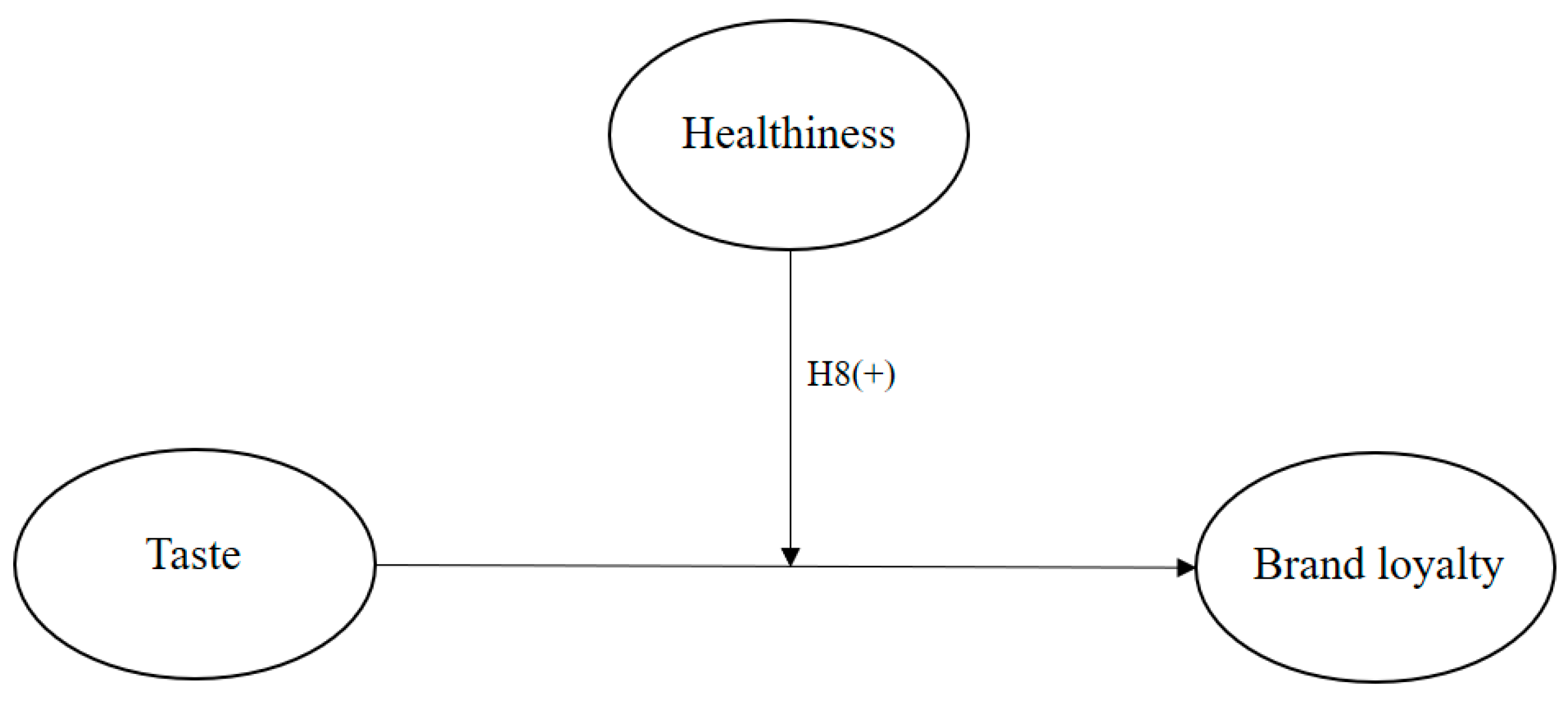

2.4. Moderating Effect of Healthiness for the Relationship between Taste and Brand Loyalty

3. Methods

3.1. Research Model

3.2. Measurements and Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Profile of Survey Participants

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Correlation Matrix

4.3. Results of Hypotheses Testing Using Structural Equation Model

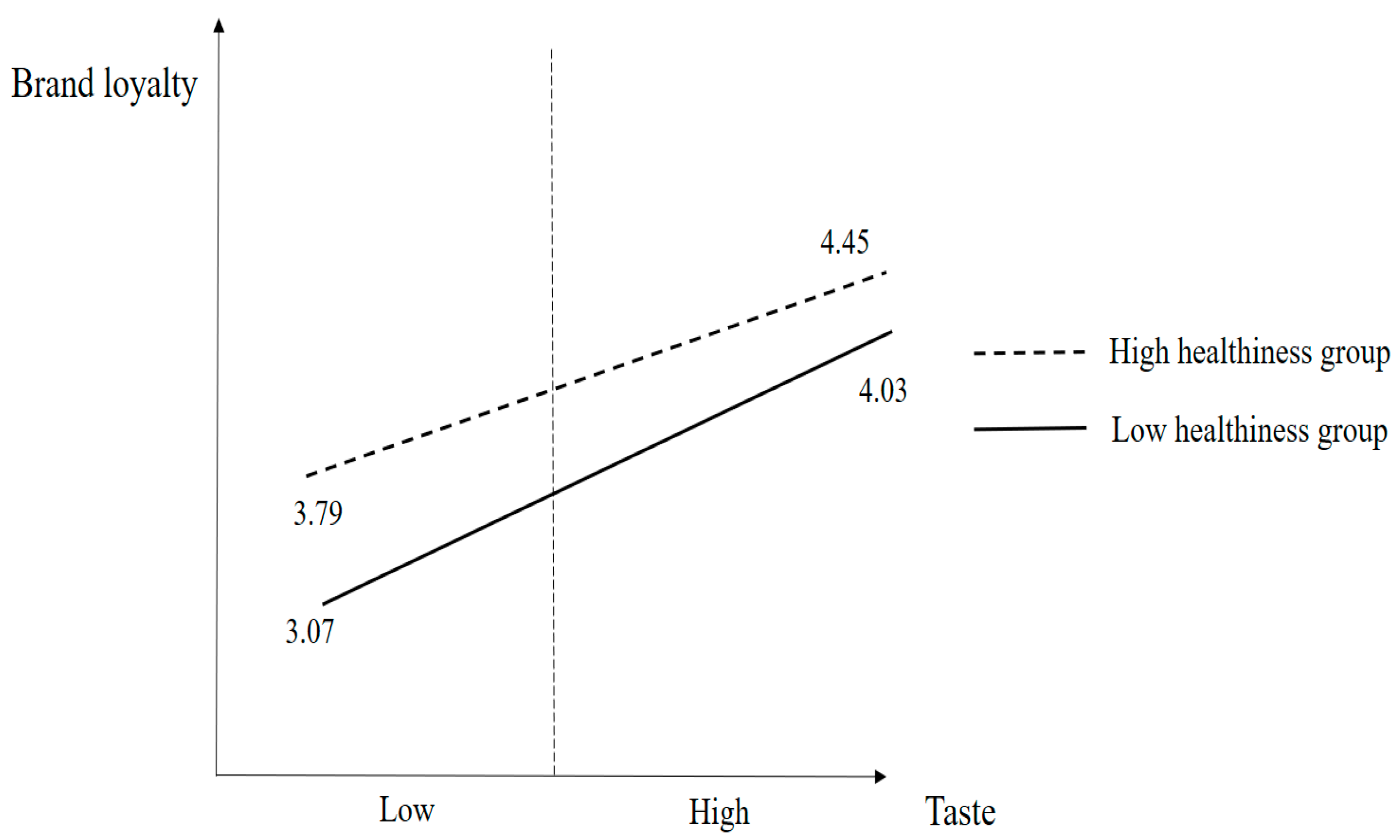

4.4. Results of Hypotheses Testing Using Structural Equation Model

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Managerial Implications

6.3. Suggestions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shake Shack. Standing for Something Good. 2021. Available online: https://www.shakeshack.com/stand-for-something-good/ (accessed on 4 October 2023).

- Mackenbach, J.D.; Lakerveld, J.; Generaal, E.; Gibson-Smith, D.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Beulens, J.W.J. Local fast-food environment, diet and blood pressure: The moderating role of mastery. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 3129–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soua, S.; Ghammam, R.; Maatoug, J.; Zammit, N.; Ben Fredj, S.; Martinez, F.; Ghannem, H. The prevalence of high blood pressure and its determinants among Tunisian adolescents. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2022, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhaddad, A. A structural model of the relationships between brand image, brand trust and brand loyalty. Int. J. Manag. Res. Rev. 2015, 5, 137. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, H.; Perks, H. Effects of consumer perceptions of brand experience on the web: Brand familiarity, satisfaction and brand trust. J. Consum. Behav. Int. Res. Rev. 2005, 4, 438–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.; Kim, J. Effects of brand personality on brand trust and brand affect. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 27, 639–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Naggar, R.; Bendary, N. The impact of experience and brand trust on brand loyalty, while considering the mediating effect of brand equity dimensions, an empirical study on mobile operator subscribers in Egypt. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2017, 9, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Huaman-Ramirez, R.; Merunka, D. Brand experience effects on brand attachment: The role of brand trust, age, and income. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 610–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A. Effects of brand experience on brand loyalty in Indonesian casual dining restaurant: Roles of customer satisfaction and brand of origin. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 24, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Ng, C.; Kim, Y. Influence of institutional DINESERV on customer satisfaction, return intention, and word-of-mouth. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Choi, K. Bridging the perception gap between management and customers on DINESERV attributes: The Korean all-you-can-eat buffet. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, S.; Raspor, S.; Šegarić, K. Does restaurant performance meet customers’ expectations? An assessment of restaurant service quality using a modified DINESERV approach. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 16, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QSR. Ranking the Top 50 Fast-Food Chains in America. 2021. Available online: https://www.qsrmagazine.com/content/ranking-top-50-fast-food-chains-america (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Cardello, A. Food quality: Relativity, context and consumer expectations. Food Qual. Prefer. 1995, 6, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C. Efficient or enjoyable? Consumer values of eating-out and fast food restaurant consumption in Korea. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2004, 23, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K. Food quality and safety: Consumer perception and demand. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2005, 32, 369–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Lee, H. Frequent consumption of certain fast foods may be associated with an enhanced preference for salt taste. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2009, 22, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cena, H.; Calder, P.C. Defining a healthy diet: Evidence for the role of contemporary dietary patterns in health and disease. Nutrients 2020, 12, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizabeth, L.; Machado, P.; Zinöcker, M.; Baker, P.; Lawrence, M. Ultra-processed foods and health outcomes: A narrative review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, J.; Paul, J. Health motive and the purchase of organic food: A meta-analytic review. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amar, M.; Gvili, Y.; Tal, A. Moving towards healthy: Cuing food healthiness and appeal. J. Soc. Mark. 2021, 11, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, P.; Knutson, B.; Patton, M. DINESERV: A tool for measuring service quality in restaurants. Cornell Hotel. Restaur. Adm. Q. 1995, 36, 5–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portal, S.; Abratt, R.; Bendixen, M. The role of brand authenticity in developing brand trust. J. Strat. Mark. 2019, 27, 714–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.; Jung, S.; Choi, H.; Kim, J. Antecedent factors that affect restaurant brand trust and brand loyalty: Focusing on US and Korean consumers. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2020, 30, 990–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzler, K.; Grabner-Kräuter, S.; Bidmon, S. Risk aversion and brand loyalty: The mediating role of brand trust and brand affect. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2008, 17, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehir, C.; Şahin, A.; Kitapçı, H.; Özşahin, M. The effects of brand communication and service quality in building brand loyalty through brand trust; the empirical research on global brands. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 24, 1218–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Back, K.; Kim, J. Family restaurant brand personality and its impact on customer’s emotion, satisfaction, and brand loyalty. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2009, 33, 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.J.; Yeh, T.; Pai, F.; Chen, D. Integrating refined kano model and QFD for service quality improvement in healthy fast-food chain restaurants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Moon, H. What drives customer satisfaction, loyalty, and happiness in fast-food restaurants in China? perceived price, service quality, food quality, physical environment quality, and the moderating role of gender. Foods 2020, 9, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougoure, U.; Neu, M. Service quality in the Malaysian fast food industry: An examination using DINESERV. Serv. Mark. Q. 2010, 31, 194–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szocs, C.; Lefebvre, S. The blender effect: Physical state of food influences healthiness perceptions and consumption decisions. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 54, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omari, R.; Ruivenkamp, G.; Tetteh, E. Consumers’ trust in government institutions and their perception and concern about safety and healthiness of fast food. J. Trust Res. 2017, 7, 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Reid, L.N. Promoting healthy menu choices in fast food restaurant advertising: Influence of perceived Brand healthiness, Brand commitment, and health consciousness. J. Health Commun. 2018, 23, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konuk, F.A. The impact of retailer innovativeness and food healthiness on store prestige, store trust and store loyalty. Food Res. Int. 2019, 116, 724–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Kamran, Q. A review of antecedents and effects of loyalty on food retailers toward sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.C. Taiwanese tourists’ perceptions of service quality on outbound guided package tours: A qualitative examination of the SERVQUAL dimensions. J. Vacat. Mark. 2009, 15, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumaedi, S.; Yarmen, M. Measuring perceived service quality of fast food restaurant in Islamic country: A conceptual framework. Procedia Food Sci. 2015, 3, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Prybutok, V.; Zhao, Q. Perceived service quality in fast-food restaurants: Empirical evidence from China. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2010, 27, 424–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, K. Development of SERVQUAL and DINESERV for measuring meal experiences in eating establishments. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2014, 14, 116–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alan, A.; Kabadayı, E. Quality antecedents of brand trust and behavioral intention. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 150, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, L.; Soo, K. The effect of brand experience on brand relationship quality. Acad. Mark. Stud. J. 2012, 16, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Jekanowski, M.; Binkley, J.; Eales, J. Convenience, accessibility, and the demand for fast food. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2001, 26, 58–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hanaysha, J. Testing the effects of food quality, price fairness, and physical environment on customer satisfaction in fast food restaurant industry. J. Asian Bus. Strat. 2016, 6, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanaysha, J. Restaurant location and price fairness as key determinants of brand equity: A study on fast food restaurant industry. Bus. Econ. Res. 2016, 6, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Tian, X. Food accessibility, diversity of agricultural production and dietary pattern in rural China. Food Policy 2019, 84, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemad-Sajadi, R.; Rizzuto, D. The antecedents of consumer satisfaction and loyalty in fast food industry. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2013, 30, 780–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hride, F.T.; Ferdousi, F.; Jasimuddin, S.M. Linking perceived price fairness, customer satisfaction, trust, and loyalty: A structural equation modeling of Facebook-based e-commerce in Bangladesh. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2022, 41, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, S.; Nyam-Ochir, A. The effects of fast food restaurant attributes on customer satisfaction, revisit intention, and recommendation using DINESERV scale. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohaib, M.; Wang, Y.; Iqbal, K.; Han, H. Nature-based solutions, mental health, well-being, price fairness, attitude, loyalty, and evangelism for green brands in the hotel context. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 101, 103126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, A.; Kuehn, R. The impact of servicescape on quality perception. Eur. J. Mark. 2005, 39, 785–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanks, L.; Line, N.; Kim, W. The impact of the social servicescape, density, and restaurant type on perceptions of interpersonal service quality. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 61, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Mohi, Z. Assessment of service quality in the fast-food restaurant. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2015, 18, 358–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, I.; Mattila, A. Restaurant servicescape, service encounter, and perceived congruency on customers’ emotions and satisfaction. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2010, 19, 819–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, R. A study of determinants impacting consumers food choice with reference to the fast food consumption in India. Soc. Bus. Rev. 2011, 6, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A.; Pollard, T.; Wardle, J. Development of a measure of the motives underlying the selection of food: The food choice questionnaire. Appetite 1995, 25, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitelock, E.; Ensaff, H. On your own: Older adults’ food choice and dietary habits. Nutrients 2018, 10, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papoutsi, G.S.; Klonaris, S.; Drichoutis, A. The health-taste trade-off in consumer decision making for functional snacks: An experimental approach. Bri. Food J. 2021, 123, 1645–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, L. Pretty healthy food: How and when aesthetics enhance perceived healthiness. J. Mark. 2021, 85, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahwa, R.; Arora, S.; Kaur, S. Health–Taste Trade-Off in Consumer Decision-Making for Functional Foods. Technol. Manag. Bus. 2023, 31, 127–141. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Yu, H.; Yang, B. Healthy or tasty: The impact of fresh starts on food preferences. Curr Psychnol. 2023, 42, 25292–25307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souiden, N.; Chaouali, W.; Baccouche, M. Consumers’ attitude and adoption of location-based coupons: The case of the retail fast food sector. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 47, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, J. The effect of brand–health issue fit on fast-food health-marketing initiatives. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2020, 41, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Hou, Y.; Li, G. Threat of infectious disease during an outbreak: Influence on tourists’ emotional responses to disadvantaged price inequality. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wooldridge, J. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach; South-Western College Publishing: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Anderson, R.; Babin, B.; Black, W. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective (Vol.7); Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle, R. Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Process: A Versatile Computational Tool for Observed Variable Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Modeling. 2012. Available online: http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2023).

- Liu, Y.; Pu, H.; Sun, D. Hyperspectral imaging technique for evaluating food quality and safety during various processes: A review of recent applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 69, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Code | Item |

|---|---|---|

| Taste | TA1 | Shake Shack burger is tasty. |

| TA2 | Shake Shack menu is delicious. | |

| TA3 | Shake Shack food is flavorful. | |

| TA4 | Shake Shack offers tasty food. | |

| Healthiness | HE1 | Shake Shack food is healthy. |

| HE2 | Shake Shack food is nutritional. | |

| HE3 | Shake Shack food promotes health condition. | |

| HE4 | Shake Shack food contains healthy ingredient. | |

| Employee service | ES1 | Shake Shack employees are kind. |

| ES2 | Shake Shack employees are cooperative. | |

| ES3 | Shake Shack employees are helpful. | |

| Price fairness | PF1 | Price of Shake Shack product is fair. |

| PF2 | Price of Shake Shack product is rational. | |

| PF3 | Shake Shack offers acceptable price level. | |

| PF4 | Shake Shack product price is reasonable. | |

| Ambience | AM1 | Shake Shack store is clean. |

| AM2 | Shake Shack store cleanliness is administered well. | |

| AM3 | Shake Shack offers comfort dining ambience. | |

| AM4 | Shake Shack provides restful dining condition. | |

| AM5 | Shake Shack store is cozy. | |

| Convenience | CO1 | Shake Shack store is accessible. |

| CO2 | Shake Shack product is easy to reach. | |

| CO3 | Shake Shack is convenient to visit. | |

| Brand trust | BT1 | Shake Shack is credible brand. |

| BT2 | Shake Shack brand is trustworthy. | |

| BT3 | Shake Shack is reliable brand. | |

| BT4 | I trust Shake Shack brand name. | |

| Brand loyalty | BL1 | I continue to use Shake Shack brand. |

| BL2 | I am loyal to Shake Shack brand. | |

| BL3 | Shake Shack brand deserves to purchase again. | |

| BL4 | I would recommend Shake Shack brand to others. |

| Item | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Male | 199(56.4) |

| Female | 154(43.6) |

| 20–29 years old or younger | 83(23.5) |

| 30–39 years old | 174(49.3) |

| 40–49 years old | 65(18.4) |

| 50–59 years old | 18(5.1) |

| Older than 60 years old | 13(3.7) |

| Monthly household income | |

| Less than $2000 | 70(19.8) |

| Between $2000 and $3999 | 117(33.1) |

| Between $4000 and $5999 | 82(23.2) |

| Between $6000 and $7999 | 37(10.5) |

| Between $8000 and $9999 | 19(5.4) |

| More than $10,000 | 28(7.9) |

| Monthly visiting frequency | |

| Less than 1 time | 125(35.4) |

| 1~2 times | 165(46.7) |

| 3~5 times | 52(14.7) |

| More than 5 times | 11(3.1) |

| Total | 353(100.0) |

| Construct (AVE) | Code | Mean | Loading | Critical Ratio | Construct Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taste (0.707) | TA1 | 4.14 | 0.859 | 0.906 | |

| TA2 | 4.11 | 0.835 | 19.657 * | ||

| TA3 | 4.12 | 0.815 | 18.878 * | ||

| TA4 | 4.19 | 0.854 | 20.385 * | ||

| Healthiness (0.784) | HE1 | 3.08 | 0.877 | 0.784 | |

| HE2 | 3.20 | 0.880 | 23.070 * | ||

| HE3 | 3.06 | 0.901 | 24.208 * | ||

| HE4 | 3.26 | 0.884 | 23.304 * | ||

| Employee service (0.717) | ES1 | 4.01 | 0.844 | 0.884 | |

| ES2 | 4.09 | 0.849 | 19.147 * | ||

| ES3 | 4.11 | 0.848 | 19.123 * | ||

| Price fairness (0.635) | PF1 | 3.78 | 0.780 | 0.874 | |

| PF2 | 3.81 | 0.716 | 13.798 * | ||

| PF3 | 3.78 | 0.832 | 16.422 * | ||

| PF4 | 3.81 | 0.853 | 16.886 * | ||

| Ambience (0.597) | AM1 | 4.07 | 0.761 | 0.881 | |

| AM2 | 4.03 | 0.739 | 14.163 * | ||

| AM3 | 3.85 | 0.792 | 15.326 * | ||

| AM4 | 3.87 | 0.811 | 15.752 * | ||

| AM5 | 3.69 | 0.757 | 14.546 * | ||

| Convenience (0.674) | CO1 | 3.94 | 0.839 | 0.861 | |

| CO2 | 3.83 | 0.842 | 18.011 * | ||

| CO3 | 3.64 | 0.780 | 16.343 * | ||

| Brand trust (0.692) | BT1 | 3.96 | 0.802 | 0.900 | |

| BT2 | 3.95 | 0.836 | 17.918 * | ||

| BT3 | 4.01 | 0.852 | 18.407 * | ||

| BT4 | 3.98 | 0.836 | 17.923 * | ||

| Brand loyalty (0.672) | BL1 | 3.97 | 0.815 | 0.891 | |

| BL2 | 3.53 | 0.754 | 15.909 * | ||

| BL3 | 3.95 | 0.863 | 19.244 * | ||

| BL4 | 3.91 | 0.843 | 18.605 * |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Taste | 0.841 | |||||||

| 2. Healthiness | 0.395 * | 0.885 | ||||||

| 3. Employee service | 0.635 * | 0.385 * | 0.847 | |||||

| 4. Price fairness | 0.573 * | 0.495 * | 0.652 * | 0.797 | ||||

| 5. Ambience | 0.667 * | 0.552 * | 0.791 * | 0.666 * | 0.773 | |||

| 6. Convenience | 0.646 * | 0.485 * | 0.698 * | 0.680 * | 0.760 * | 0.821 | ||

| 7. Brand trust | 0.798 * | 0.460 * | 0.770 * | 0.644 * | 0.768 * | 0.687 * | 0.832 | |

| 8. Brand loyalty | 0.791 * | 0.562 * | 0.741 * | 0.693 * | 0.796 * | 0.695 * | 0.885 * | 0.820 |

| Hypothesis | Path | β(t-Value) | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | Taste → Brand trust | 0.442(7.79) * | Supported |

| H1b | Taste → Brand loyalty | 0.190(3.10) * | Supported |

| H2a | Healthiness → Brand trust | 0.045(1.01) | Not supported |

| H2b | Healthiness → Brand loyalty | 0.129(3.19) * | Supported |

| H3a | Employee service → Brand trust | 0.293(3.96) * | Supported |

| H3b | Employee service → Brand loyalty | 0.022(0.31) | Not supported |

| H4a | Price fairness → Brand trust | 0.061(1.05) | Not supported |

| H4b | Price fairness → Brand loyalty | 0.110(2.11) * | Supported |

| H5a | Ambience → Brand trust | 0.176(2.04) * | Supported |

| H5b | Ambience → Brand loyalty | 0.162(2.05) * | Supported |

| H6a | Convenience → Brand trust | 0.001(0.01) | Not supported |

| H6b | Convenience → Brand loyalty | −0.038(−0.60) | Not supported |

| H7 | Brand trust → Brand loyalty | 0.488(5.82) * | Supported |

| Variable | β(t-Value) |

|---|---|

| Constant | −0.559(−1.43) |

| Taste | 0.868(9.35) * |

| Healthiness | 0.567(3.83) * |

| Taste × Healthiness | −0.073(−2.20) * |

| F-value | 163.78 * |

| R-square | 0.5847 * |

| Conditional effect of healthiness | |

| Healthiness (2) | 0.7214(15.59) * |

| Healthiness (3.25) | 0.6291(12.25) * |

| Healthiness (4.25) | 0.5554(7.45) * |

| Test of unconditional interaction | |

| F-value | 4.86 * |

| R-square change | 0.0058 |

| Group | Low Taste | High Taste |

|---|---|---|

| High healthines | 3.79 | 4.45 |

| Low healthiness | 3.07 | 4.03 |

| Group | Gender | Age | Monthly Household Income | Monthly Using Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taste | 0.021 | 1.543 | 0.399 | 15.700 * |

| Healthiness | 7.845 * | 0.724 | 2.715 | 21.027 * |

| Employee service | 1.053 | 0.207 | 0.596 | 10.904 * |

| Price fairness | 1.866 | 0.642 | 0.118 | 11.536 * |

| Ambience | 0.596 | 0.797 | 0.431 | 11.575 * |

| Convenience | 0.945 | 0.414 | 2.963 | 16.341 * |

| Brand trust | 0.129 | 1.058 | 0.253 | 16.072 * |

| Brand loyalty | 0.996 | 0.095 | 0.475 | 24.713 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, K.-A.; Moon, J. Assessing Antecedents of Restaurant’s Brand Trust and Brand Loyalty, and Moderating Role of Food Healthiness. Nutrients 2023, 15, 5057. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15245057

Sun K-A, Moon J. Assessing Antecedents of Restaurant’s Brand Trust and Brand Loyalty, and Moderating Role of Food Healthiness. Nutrients. 2023; 15(24):5057. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15245057

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Kyung-A, and Joonho Moon. 2023. "Assessing Antecedents of Restaurant’s Brand Trust and Brand Loyalty, and Moderating Role of Food Healthiness" Nutrients 15, no. 24: 5057. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15245057

APA StyleSun, K.-A., & Moon, J. (2023). Assessing Antecedents of Restaurant’s Brand Trust and Brand Loyalty, and Moderating Role of Food Healthiness. Nutrients, 15(24), 5057. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15245057