Abstract

Background: Weight management during pregnancy and the postpartum period is an important strategy that can be utilized to reduce the risk of short- and long-term complications in women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). We conducted a systematic review to assess and synthesize evidence and recommendations on weight management during pregnancy and the postpartum period in women with GDM to provide evidence-based clinical guidance. Methods: Nine databases and eighteen websites were searched for clinical decisions, guidelines, recommended practices, evidence summaries, expert consensus, and systematic reviews. Results: A total of 12,196 records were retrieved and fifty-five articles were included in the analysis. Sixty-nine pieces of evidence were summarized, sixty-two of which focused on pregnancy, including benefits, target population, weight management goals, principles, weight monitoring, nutrition assessment and counseling, energy intake, carbohydrate intake, protein intake, fat intake, fiber intake, vitamin and mineral intake, water intake, dietary supplements, sugar-sweetened beverages, sweeteners, alcohol, coffee, food safety, meal arrangements, dietary patterns, exercise assessment and counseling, exercise preparation, type of exercise, intensity of exercise, frequency of exercise, duration of exercise, exercise risk prevention, and pregnancy precautions, and seven focused on the postpartum period, including target population, benefits, postpartum weight management goals, postpartum weight monitoring, dietary recommendations, exercise recommendations, and postpartum precautions. Conclusions: Healthcare providers can develop comprehensive pregnancy and postpartum weight management programs for women with GDM based on the sixty-nine pieces of evidence. However, because of the paucity of evidence on postpartum weight management in women with GDM, future guidance documents should focus more on postpartum weight management in women with GDM.

1. Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a common complication of pregnancy characterized by glucose intolerance with onset or first recognition during pregnancy [1]. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) defines GDM as “diabetes mellitus diagnosed at 24~28 weeks of gestation, excluding pregnant women with previously recognized diabetes mellitus or high-risk abnormalities of glucose metabolism detected early in the current pregnancy” [2]. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), the prevalence of GDM in 2021 is estimated to be 16.7% worldwide [3]. With socioeconomic development, lifestyle changes, and improvements in assisted reproductive technology, the prevalence of GDM will increase as the proportion of women who are overweight or obese before pregnancy rises and the number of pregnant women of advanced maternal age increases [4,5]. GDM not only adversely affects the mother and fetus by increasing the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as pre-eclampsia, cesarean section, shoulder dystocia, preterm birth, macrosomia, and congenital malformations, but it also significantly increases a woman’s lifetime risk of several diseases, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), cardiovascular disease, renal disease, and cancer [6,7,8,9,10]. Therefore, it is of vital importance to manage GDM to minimize the complications.

Excessive gestational weight gain (EGWG) increases the risk of short- and long-term complications of GDM. A previous study found that pregnant women with EGWG had a higher risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as large for gestational age (OR 2.06; 95%CI 1.44~2.93), macrosomia (OR 2.20; 95%CI 1.50~3.25), cesarean section (OR 1.45; 95%CI 1.13~1.87), and neonatal hypoglycemia (OR 3.80; 95%CI 1.20~12.00), compared with those with appropriate weight gain during pregnancy [11]. For each 1-unit increase in BMI during pregnancy, the risk of long-term T2DM increased by 16% (HR 1.16; 95%CI: 1.12~1.19) [12]. To make matters worse, postpartum weight retention (PWR) and obesity also pose a serious health threat to women with GDM. Women with high early PWR have more impaired metabolic profiles, less frequent breastfeeding, higher rates of depression, higher levels of anxiety, and lower quality of life in the postpartum period compared with women with early PWR < 5 kg [13]. For each 5 kg increase in postpartum body weight, the risk of long-term T2DM increased by 27% (HR 1.27; 95%CI 1.04~1.54) [12]. The above evidence suggests that weight is an important and modifiable intervention target throughout pregnancy and postpartum to reduce the risk of short- and long-term complications of GDM.

In recent years, weight management strategies for GDM including weight control, dietary modification, and appropriate exercise have received increased attention, and various medical guidance documents have been published to provide support and recommendations for healthcare providers to guide women with GDM to engage in healthy weight-related behaviors to optimize their weight during pregnancy and the postpartum period. The overall goal of these medical guidance documents is to optimize patient care based on systematic evidence [14]. However, in terms of content, there are differences in the recommendations of these literature sources, and each one does not cover precisely the same content even though the subject is the same; in terms of quality, the recommendations of more methodologically rigorous literature sources may be more scientific, and the differences in the methodological rigor may result in the dilution of high-quality recommendations; and in terms of publication time, the content of the literature may change over time, and the recommendations of more recently published research from the literature may be more appropriate for the current population [15,16]. All of the above issues may lead to uncertainty when it comes to clinical practice.

To address this issue, we conducted a systematic review of specific aspects of weight management during pregnancy and the postpartum period in women with GDM to assess, extract, and synthesize the available high-level evidence from the last five years, to provide clinical references for weight management during pregnancy and the postpartum period in women with GDM, and to facilitate more scientific decision making by healthcare providers.

2. Methods

In accordance with the protocol (CRD42023451857, https://www.crd.york.ac.uk), we conducted this systematic review. The report followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [17].

2.1. Establishment of the Problem

The initial questions were developed using the PIPOST principles, a problem development tool from the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Evidence-Based Nursing Collaboration Center at Fudan University. In this study, the target population for the evidence refers to women with GDM or postpartum women with a history of GDM; the intervention measures refer to weight control (recommendations or measures for weight gain prevention, weight loss, weight management goals, weight monitoring, etc.), diet management (recommendations or measures for eating patterns, food types, energy, nutrients, etc.), and exercise management (recommendations or measures for exercise type, intensity, frequency, duration, etc.) during pregnancy and the postpartum period; professionals (evidence implementers) refer to medical staff; outcomes refer to weight (BMI changes, gestational weight gain, PWR, etc.), blood glucose (blood glucose, glycated hemoglobin, postpartum glucose metabolism outcome, long-term T2DM incidence, etc.), maternal outcomes (hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, depression, anxiety, etc.), pregnancy outcomes (mode of delivery, premature delivery, dystocia, stillbirth, premature rupture of membranes, birth injury, etc.), and neonatal outcomes (macrosomia, neonatal hypoglycemia, respiratory distress, perinatal death, etc.); settings (site of application of evidence) refer to medical institutions, postpartum rehabilitation centers, and families; and the type of study refers to clinical decisions, guidelines, recommended practices, evidence summaries, expert consensus, and systematic reviews.

2.2. Evidence Sources and Retrieval Strategies

Between 2018 and April 2023, we systematically searched national and international specific websites and databases, including BMJ Clinical Evidence, UpToDate, World Health Organization, Guidelines International Network, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Queensland Health, Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario, Canadian Medical Association: Clinical Practice Guideline, Federation International of Gynecology and Obstetrics, ADA, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada, Cnadian Diabetes Association, IDF, Chinese Medlive Guideline, All EBM Reviews, JBI EBP Database, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science, CNIK, Wanfang, and SinoMed. A combination of subject terms and text words was used to search in databases. The search strategy for databases and websites is described in Supplementary Table S1.

2.3. Inclusion Criteria and Study Selection

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) the subjects were women with gestational diabetes mellitus or postpartum women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus; (2) the content or interventions relate to weight management during pregnancy and the postpartum period, including weight control (recommendations or measures for weight gain prevention, weight loss, weight management goals, weight monitoring, etc.), diet management (recommendations or measures for eating patterns, food types, energy, nutrients, etc.), and exercise management (recommendations or measures for exercise type, exercise intensity, exercise frequency, exercise duration, etc.); (3) the outcomes involved weight (BMI changes, gestational weight gain, PWR, etc.), blood glucose (blood glucose, glycated hemoglobin, postpartum glucose metabolism outcome, long-term T2DM incidence, etc.), maternal outcomes (hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, depression, anxiety, etc.), pregnancy outcome (mode of delivery, premature delivery, dystocia, stillbirth, premature rupture of membranes, birth injury, etc.), and neonatal outcomes (macrosomia, neonatal hypoglycemia, respiratory distress, perinatal death, etc.); (4) the publication types were clinical decisions, guidelines, recommended practices, expert consensus, evidence summaries, and systematic reviews; (5) published in Chinese or English; and (6) published or updated from 2018 to 2023. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) unable to get the full text; (2) studies without reference list; (3) duplicate publications; or (4) studies with the background restricted to COVID-19.

Based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, two researchers (H. J. and L. H.) independently screened titles and abstracts to select articles for full-text review, and then a full-text review was conducted to identify articles for inclusion in the quality assessment. Any disagreements were discussed with another researcher (W. Y.) until a consensus conclusion was reached.

2.4. Quality Assessment

Study quality was assessed independently by two researchers (H. J. and L. H.) according to the following instruments. Any disagreements were discussed with another researcher (W. Y.) until a consensus conclusion was reached.

2.4.1. Evaluation of Guidelines

The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation Instrument II (AGREE II) was used to appraise the quality of the guidelines, consisting of twenty-three items and six domain [18]. The overall quality of the guidelines was graded as follows: guidelines with six domains scoring > 60% were considered graded A (high quality); guidelines with three or more domains scoring > 30% were considered graded B (average quality); and guidelines with three or more domains scoring < 30% were considered graded C (poor quality). Guidelines rated “C” were not included in this study.

2.4.2. Evaluation of Systematic Reviews

Evaluation of systematic reviews was carried out using the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews 2 (AMSTAR 2), which included sixteen items [19]. According to the seven key items (2, 4, 7, 9, 11, 13, and 15) selected by the AMSTAR 2 research team that affected the production of systematic reviews and the validity of their results, the quality of systematic reviews was divided into four levels: high, medium, low, and very low. Systematic reviews rated “very low” were not included in this study.

2.4.3. Evaluation of Clinical Decisions, Recommended Practice, and Expert Consensus

The quality assessment instrument of the Australian JBI Evidence-Based Health Care Center for text and opinion papers was used to assess the quality of clinical decisions, expert consensus, and recommended practices [20]. The instrument consisted of six items, each rated “yes”, “no”, “unclear”, and “not applicable”. The inclusion and exclusion of articles were determined by group discussion.

2.4.4. Evaluation of Evidence Summaries

Critical Appraisal for Summaries of Evidence (CASE) was used to assess the quality of evidence summaries [21]. The instrument contained ten items, each rated “yes”, “partially yes”, and “no”. The inclusion and exclusion of articles were determined by group discussion.

2.5. Data Extraction

Data extraction was performed by two researchers (H. J. and L. H.) independently using prespecified data extraction forms. Any disagreements were discussed with another researcher (W. Y.) until a consensus conclusion was reached. Data extracted included year of publication or update, publication country or region, authors, study type, target population, and content related to weight management during pregnancy and the postpartum period in women with GDM.

2.6. Data Synthesis and Classification

The qualitative synthesis and classification of evidence were also performed by two researchers (H. J. and L. H.) independently. Any disagreements were discussed in the group until a consensus conclusion was reached. Principles of synthesis: (1) if the content was consistent, evidence that was concise and easy to understand was selected; (2) if the content was complementary, it was merged based on linguistic logic; and (3) if the content was contradictory, the selection was based on the principles of prioritizing evidence-based evidence, prioritizing high-quality evidence, and prioritizing the most recently published authoritative literature. When the evidence synthesis was completed, the original study on which the relevant evidence was based was traced. According to the study design and the JBI evidence Pre-classification System (2014), the evidence level was divided into I to V levels, with I being the highest level and V being the lowest level [22].

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

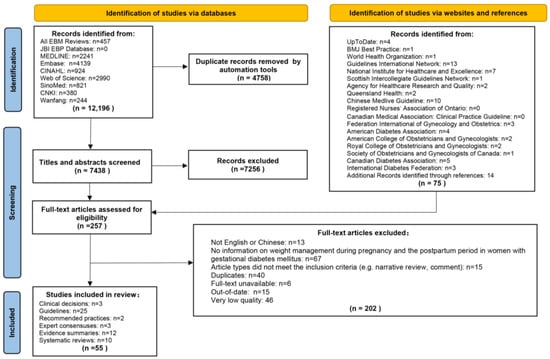

A total of 12,196 articles were retrieved. After excluding 4758 duplicates, the titles and abstracts of the remaining 7438 articles were reviewed. Based on the title and abstract review, 7256 unrelated articles were excluded, leaving 182 articles. In total, 75 articles were obtained from websites and references. Therefore, a total of 257 full-text articles were reviewed. The results of the full-text review showed that 202 articles did not meet the inclusion criteria, of which 13 articles were published in languages other than English or Chinese, 67 articles did not have information on weight management during pregnancy and the postpartum period in women with GDM, 5 articles did not meet the inclusion criteria for study types, 40 articles were duplicated, 6 articles were not available for full text, 15 articles were published beyond the specified time limit, and 46 articles were rated as very low quality. Finally, we included three clinical decisions, twenty-five guidelines, two recommended practices, three expert consensuses, twelve evidence summaries, and ten systematic reviews. The flow diagram of literature search and selection is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of literature search and screen.

3.2. Quality Assessment

3.2.1. Quality Evaluation Results of Guidelines

Of the twenty-five guidelines included in the evidence extraction, five were from the United States of America [23,24,25,26,27], three from China [28,29,30], two from the United Kingdom [31,32], two from Canada [33,34], two from Japan [35,36], two from Iran [37,38], one from Greece [39], one from India [40], one from Turkey [41], one from Pakistan [42], one from MENA region [43], one from Poland [44], one from Qatar [45], one from Australia [1], and one from Germany [46]. According to the AGREE II, the average scores of the six domains were as follows: scope and purpose = 87.78%; stakeholder involvement = 61.00%; rigor of development = 57.29%; clarity of presentation = 82.56%; applicability = 44.25%; and editorial independence = 75.50%. In this study, four guides were rated as grade A, and twenty-one were rated as grade B. The characteristics of the guidelines and the scores for each domain are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

3.2.2. Quality Evaluation Results of Systematic Reviews

Of the ten systematic reviews included in the evidence extraction, there were one from the Cochrane database [47], five from the MEDLINE database [48,49,50,51,52], three from the CINAHL database [53,54,55], and one from the Embase database [56]. One study was a review of systematic reviews [47], one study included both randomized controlled trials and observational studies [53], and the original study for all other studies was randomized controlled trials [48,49,50,51,52,54,55,56]. Six systematic reviews were of women with GDM, two of which focused on lifestyle interventions [47,54], and four of which focused on dietary changes only [50,51,52,55]. Four systematic reviews were of women with prior GDM, three of which focused on lifestyle interventions [48,49,56] and one on dietary interventions only [53]. Of the ten systematic reviews, one was of high quality [47], two were of medium quality [51,56], and seven were of low quality [48,49,50,52,53,54,55]. The results of the quality assessment of the systematic reviews are presented in Supplementary Table S3.

3.2.3. Quality Evaluation Results of Evidence Summaries

After a group discussion, all evidence summaries were deemed to be of acceptable quality and were included in evidence extraction, of which eight were from the JBI EBP Database [57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64], and four were from the Wanfang [65,66,67,68]. Of the twelve evidence summaries, one evidence summary focused on lifestyle interventions for GDM [62], seven focused on dietary management for GDM [58,61,63,64,65,66,68], two focused on exercise management for GDM [60,67], one focused on antenatal care for GDM [57], and one focused on education for GDM [59]. The results of the quality assessment of the evidence summaries are presented in Supplementary Table S4.

3.2.4. Quality Evaluation Results of Other Studies

After group discussion, all clinical decisions, recommended practices, and expert consensus were deemed to be of acceptable quality for inclusion in the evidence extraction. A total of three clinical decisions were included, one from BMJ Best Practice [69] and two from UpToDate [70,71]. Two recommended practices and three expert consensus were included in total, two focused on GDM [72,73], one focused on the prevention of T2DM in women with prior GDM [74], one focused on exercise during pregnancy [75], and one focused on pregnancy after bariatric surgery [76]. The results of the quality assessment of the clinical decisions, recommended practice, and expert consensus are presented in Supplementary Table S5.

3.3. Synthesis of Evidence

We summarized sixty-two pieces of evidence about weight management of women with GDM during pregnancy, including target population, benefits, weight management goals, principles, weight monitoring, nutrition assessment and counseling, energy intake, carbohydrate intake, protein intake, fat intake, fiber intake, vitamin and mineral intake, water intake, dietary supplements, sugar-sweetened beverages, sweeteners, alcohol, coffee, food safety, meal arrangements, dietary patterns, exercise assessment and counseling, exercise preparation, type of exercise, intensity of exercise, frequency of exercise, duration of exercise, exercise risk prevention, and precautions during pregnancy. We also summarized seven pieces of evidence about postpartum weight management of women with prior GDM, including target population, benefits, postpartum weight management goals, postpartum weight monitoring, dietary recommendations, exercise recommendations, and postpartum precautions. The evidence above can be divided into four categories: weight control during pregnancy, diet management during pregnancy, exercise management during pregnancy, and comprehensive postpartum management. There were fifteen level I and fifty-four level V pieces of evidence. The evidence is summarized in Table 1. Key recommendations on weight gain goals, total energy intake, nutrients, and physical activity from the guidelines are presented in Supplementary Table S6.

Table 1.

The evidence on weight management during pregnancy and postpartum period in women with GDM.

3.4. The Proportion of Carbohydrates, Proteins, and Fats in Daily Energy Intake

The recommended proportion of nutrient intake to daily energy intake for women with GDM varied considerably across the literature. The reported percentages of carbohydrates to daily energy intake were 33~40% [72], 35~45% [39,43,73,77], 40~45 [46], 40~50% [41,44], 40~55% [27], 50% [38], and 50~60% [28]. The reported percentages of proteins to total daily energy intake were 15~20% [77], 15~25% [45], 15~30% [41], 20% [38], 20~25% [39,43], and 20~30% [44]. The reported percentages of fats to daily energy intake were 20~30% [44], 20~35% [41], 25~30% [77], 25~35% [43], 30% [38], 30~35% [46], 30~40% [27,39,45], and 40% [70]. Some literature sources recommended that saturated fat intake in women with GDM should not exceed 7% of daily energy intake [28,43,70,72], while others recommended that it should not exceed 10% of daily energy intake [27,41,44,45].

4. Discussion

This study reviewed and summarized the evidence and recommendations for weight management during pregnancy and the postpartum period in women with GDM. Our results found that the evidence and recommendations for weight management during pregnancy and the postpartum period for women with GDM were categorized as weight control during pregnancy, diet management during pregnancy, exercise management during pregnancy, and postpartum management. Overall, the evidence and recommendations for weight management during pregnancy in women with GDM were comprehensive, but there were differences in some areas; whereas the evidence and recommendations for postpartum weight management in women with GDM were few, and the content was general and not detailed. This systematic review provided information and references for the clinical practice of weight management during pregnancy and the postpartum period in women with GDM. The lack of postpartum weight management evidence indicated the necessity of developing high-quality guidance documents to guide the whole process of weight management of women with GDM during pregnancy and the postpartum period.

Weight management was not only the cornerstone of GDM management but also a core strategy for preventing short- and long-term complications of GDM [11,12,13]. We extracted seven pieces of evidence about weight control covering benefits, target population, principles, weight management goals, and weight monitoring. All women diagnosed with GDM should control weight according to their pre-pregnancy BMI. However, we found that the guidance documents from different countries had different recommendations for weight gain during pregnancy, which may be caused by different BMI classifications for different national populations. For example, the World Health Organization’s BMI classifications are not all the same as those commonly used in the Chinese population [28,46]. Therefore, in this systematic review, we present two different recommendations for weight gain during pregnancy for different populations. In addition, healthcare providers should record the pre-pregnancy BMI of women with GDM and assess weight changes at each of their visits, and the women themselves should monitor their weight weekly.

Diet management is one of the most crucial methods for achieving weight control goals in women with GDM. We extracted thirty-four pieces of evidence covering nutrition assessment and counseling, energy intake, carbohydrate intake, protein intake, fat intake, fiber intake, vitamin and mineral intake, water intake, dietary supplements, sugar-sweetened beverages, sweeteners, alcohol, coffee, food safety, meal arrangements, and dietary patterns. Healthcare providers should conduct a comprehensive nutritional assessment, provide nutritional counseling, and develop a personalized dietary management plan for women with GDM at their first visit. It is worth noting that women with GDM should not excessively restrict their energy intake, and their total daily calorie intake should be determined according to their pre-pregnancy BMI and stage of pregnancy. Interestingly, although only sources from the literature from the last five years were selected for this systematic review and very low-quality literature was excluded, the recommended proportion of nutrient intake to daily energy intake for women with GDM varied considerably across the literature. Dietary habits and body metabolism may vary among populations in different countries, which may explain the differences in the proportion of the above nutrients to daily energy intake in different literature studies. However, this study found differences in the ratio of nutrient intake to daily energy intake recommended in the guidance documents from the same country [28,77]. These different recommendations may lead to uncertainty in clinical implementation.

Exercise management is another crucial method for women with GDM to achieve weight control goals. We extracted twenty pieces of evidence covering exercise assessment and counseling, exercise preparation, type of exercise, intensity of exercise, frequency of exercise, duration of exercise, and exercise risk prevention. As with dietary management, professionals should conduct a comprehensive medical assessment and exercise counseling for women with GDM. However, this study found that some guidance documents listed both absolute and relative contraindications to exercise during pregnancy [34,43,67], whereas others simply listed contraindications without distinguishing between the two [1,28,77]. Pregnant women with absolute contraindications to exercise are not advised to exercise, while those with relative contraindications to exercise may exercise appropriately based on professional advice. The different delineation of contraindications to exercise by different guidelines may increase uncertainty when it comes to clinical implementation. Moderate-intensity aerobic exercise and light resistance exercise, such as walking, brisk walking, stationary biking, swimming, modified yoga, Pilates, and stretching, are appropriate for women with GDM, but exercise that may be harmful to the mother or fetus should be avoided. It is worth noting that given the different physical conditions and personal preferences of women with GDM, exercise plans should be individualized, with an emphasis on increasing physical activity and decreasing sedentary time.

Postpartum weight management in women with GDM is an effective strategy for preventing long-term complications of GDM. However, we found that there is little and generic evidence for postpartum weight control, diet management, and exercise management in women with GDM. We only extracted six pieces of evidence covering the target population, benefits, postpartum weight management goals, postpartum weight monitoring, dietary recommendations, and exercise recommendations. Laboratory and anthropometric indicators such as blood glucose, lipids, weight, and waist circumference should be tested in women with GDM at 4~12 weeks postpartum. The postpartum weight control goal for women with normal pre-pregnancy BMI is to return to pre-pregnancy weight, and the postpartum weight control goal for women with pre-pregnancy overweight or obesity is to lose 5~7% of their pre-pregnancy weight. However, we found that current guidance documents do not state the recommended time to reach postpartum weight control goals, which may lead to uncertainty in postpartum weight goal setting and diversity of postpartum weight management failure and success rates [27,38]. Regardless of whether postpartum blood glucose returns to normal or not, a healthy diet, regular exercise, and weight control should be continued, but current guidance documents do not detail how to manage diet, exercise, and control weight in the postpartum period [31].

To our knowledge, this is the first review and synthesis of evidence and recommendations related to weight management during pregnancy and the postpartum period in women with GDM. In this study, we used a robust search strategy to identify different types of guidance documents, searching not only commonly used databases but also some specific websites to maximize the selection of the entire available literature, and we selected only the literature from the last five years to ensure that the evidence and recommendations obtained were more applicable to the current population. Moreover, we used internationally recognized quality assessment tools to assess the quality of the included literature and very low-quality literature was not included in the analysis, suggesting that the sources of sixty-nine pieces of evidence were all reliable. However, we may not have retrieved all available guidance documents because we only included literature studies published in English or Chinese, which led to the omission of domestic guidance documents published in certain countries.

5. Conclusions

Weight management during pregnancy and the postpartum period is a crucial strategy to reduce the short- and long-term complications of GDM. The sixty-nine pieces of evidence in this study provide scientific and practical guidance for healthcare providers on weight management during pregnancy and the postpartum period for women with GDM. The paucity of evidence on postpartum weight management in women with GDM, the lack of continuity in weight management during pregnancy and the postpartum period, and the discrepancy between the recommendations of different guidance documents in the same country suggest that more comprehensive and high-quality guidance documents are needed to lead the way in the whole process of weight management in pregnancy and postpartum for women with GDM in the future.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu15245022/s1, Table S1: Search strategy for databases and websites; Table S2: The characteristics of the guidelines and the scores for each domain; Table S3: The quality assessment of the systematic reviews; Table S4: The quality assessment of the evidence summaries; Table S5: The quality assessment of the expert consensus, recommended practices, and clinical decisions; Table S6: Key recommendations on weight gain goals, total energy intake, nutrients, and physical activity from guidelines.

Author Contributions

J.H. contributed to the literature search, literature screening, data extraction, literature quality assessment, data synthesis, and manuscript writing, and was responsible for manuscript revision. Y.W. contributed to the literature search, literature screening, data extraction, literature quality assessment, and data synthesis. H.L. contributed to the literature screening, data extraction, literature quality assessment, and data synthesis. H.C., Q.Z., T.L. and Y.Z. contributed to the literature search, provided constructive suggestions regarding the content of the manuscript, and were part of the literature quality discussion group. M.L. raised research questions and is the guarantor of this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 72074008, 72174008), the International Institute of Population Health of Peking University Health Science Center (grant number: JKCJ202304), the Capital Health Development Research Fund (grant number: 2022-1G-4252), and the Peking University Nursing Discipline Research and Development Fund (grant number: LJRC23YB03).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and supplementary materials.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mo Yi for his support for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Queensland Health. Queensland Clinical Guidelines: Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM). Available online: http://health.qld.gov.au/qcg (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Elsayed, N.A.; Aleppo, G.; Aroda, V.R.; Bannuru, R.R.; Brown, F.M.; Bruemmer, D.; Collins, B.S.; Hilliard, M.E.; Isaacs, D.; Johnson, E.L.; et al. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, S19–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas. Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org/data/en/indicators/14/ (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Manrique-Acevedo, C.; Chinnakotla, B.; Padilla, J.; Martinez-Lemus, L.A.; Gozal, D. Obesity and cardiovascular disease in women. Int. J. Obes. 2020, 44, 1210–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attali, E.; Yogev, Y. The impact of advanced maternal age on pregnancy outcome. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Obs. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 70, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Luo, C.; Huang, J.; Li, C.; Liu, Z.; Liu, F. Gestational diabetes mellitus and adverse pregnancy outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2022, 377, e067946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, A.A.; Devi Rajeswari, V. Gestational diabetes mellitus-A metabolic and reproductive disorder. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 143, 112183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vounzoulaki, E.; Khunti, K.; Abner, S.C.; Tan, B.K.; Davies, M.J.; Gillies, C.L. Progression to type 2 diabetes in women with a known history of gestational diabetes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020, 369, m1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, C.K.; Campbell, S.; Retnakaran, R. Gestational diabetes and the risk of cardiovascular disease in women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2019, 62, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehmer, E.W.; Phadnis, M.A.; Gunderson, E.P.; Lewis, C.E.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Engel, S.M.; Jonsson Funk, M.; Kramer, H.; Kshirsagar, A.V.; Heiss, G. Association Between Gestational Diabetes and Incident Maternal CKD: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2018, 71, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, B.H.; Guan, H.M.; Bi, Y.X.; Ding, B.J. Gestational diabetes: Weight gain during pregnancy and its relationship to pregnancy outcomes. Chin. Med. J. 2019, 132, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.; Yeung, E.; Tobias, D.K.; Hu, F.B.; Vaag, A.A.; Chavarro, J.E.; Mills, J.L.; Grunnet, L.G.; Bowers, K.; Ley, S.H.; et al. Long-term risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in relation to BMI and weight change among women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus: A prospective cohort study. Diabetologia 2015, 58, 1212–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minschart, C.; Myngheer, N.; Maes, T.; De Block, C.; Van Pottelbergh, I.; Abrams, P.; Vinck, W.; Leuridan, L.; Driessens, S.; Mathieu, C.; et al. Weight retention and glucose intolerance in early postpartum after gestational diabetes. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2023, 19, lvad053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekelle, P.G. Clinical Practice Guidelines: What’s Next? JAMA 2018, 320, 757–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, R.; Mancher, M.; Miller Wolman, D.; Greenfield, S.; Steinberg, E. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, C.L.; Teede, H.; Khan, N.; Lim, S.; Chauhan, A.; Drakeley, S.; Moran, L.; Boyle, J. Weight management across preconception, pregnancy, and postpartum: A systematic review and quality appraisal of international clinical practice guidelines. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouwers, M.C.; Kho, M.E.; Browman, G.P.; Burgers, J.S.; Cluzeau, F.; Feder, G.; Fervers, B.; Graham, I.D.; Grimshaw, J.; Hanna, S.E.; et al. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ 2010, 182, E839–E842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McArthur, A.; Klugarova, J.; Yan, H.; Florescu, S. Chapter 4: Systematic reviews of text and opinion. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; 2020; Available online: https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-05 (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Foster, M.J.; Shurtz, S. Making the Critical Appraisal for Summaries of Evidence (CASE) for evidence-based medicine (EBM): Critical appraisal of summaries of evidence. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2013, 101, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute. JBI Levels of Evidence. Available online: https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI-Levels-of-evidence_2014_0.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Elsayed, N.A.; Aleppo, G.; Aroda, V.R.; Bannuru, R.R.; Brown, F.M.; Bruemmer, D.; Collins, B.S.; Hilliard, M.E.; Isaacs, D.; Johnson, E.L.; et al. 15. Management of Diabetes in Pregnancy: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, S254–S266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte-Gardea, M.O.; Gonzales-Pacheco, D.M.; Reader, D.M.; Thomas, A.M.; Wang, S.R.; Gregory, R.P.; Piemonte, T.A.; Thompson, K.L.; Moloney, L. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Gestational Diabetes Evidence-Based Nutrition Practice Guideline. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 1719–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 190: Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 131, e49–e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blonde, L.; Umpierrez, G.E.; Reddy, S.S.; McGill, J.B.; Berga, S.L.; Bush, M.; Chandrasekaran, S.; DeFronzo, R.A.; Einhorn, D.; Galindo, R.J.; et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline: Developing a Diabetes Mellitus Comprehensive Care Plan—2022 Update. Endocr. Pract. 2022, 28, 923–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, F.M.; Anderson-Haynes, S.E.; Blair, E.; Serdy, S.; Halprin, E.; Feldman, A.; O’Brien, K.E.; Ghiloni, S.; Suhl, E.; Rizzotto, J.A.; et al. CHAPTER 3. Guideline for detection and management of diabetes in pregnancy. Am. J. Manag. Care 2018, 24, SP232–SP239. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.X. Guideline for the diagnosis and management of hyperglycemia in pregnancy (2022) [Part I]. Chin. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 57, 3–12. Available online: https://rs.yiigle.com/CN112141202201/1349426.htm (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Branch of Women’s Health Care, C.P.M.A. Guideline to postpartum health services. Chin. J. Woman Child. Health Res. 2021, 32, 767–781. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, N.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, K.; Li, L. Update of clinical nursing practice guideline for gestational diabetes mellitus. J. Nurses Train. 2021, 36, 1937–1943. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Diabetes in Pregnancy: Management from Preconception to the Postnatal Period. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng3 (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Dyson, P.A.; Twenefour, D.; Breen, C.; Duncan, A.; Elvin, E.; Goff, L.; Hill, A.; Kalsi, P.; Marsland, N.; McArdle, P.; et al. Diabetes UK evidence-based nutrition guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes. Diabet. Med. 2018, 35, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feig, D.S.; Berger, H.; Donovan, L.; Godbout, A.; Kader, T.; Keely, E.; Sanghera, R. Diabetes and Pregnancy. Can. J. Diabetes 2018, 42, S255–S282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottola, M.F.; Davenport, M.H.; Ruchat, S.M.; Davies, G.A.; Poitras, V.J.; Gray, C.E.; Jaramillo Garcia, A.; Barrowman, N.; Adamo, K.B.; Duggan, M.; et al. 2019 Canadian guideline for physical activity throughout pregnancy. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 1339–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araki, E.; Goto, A.; Kondo, T.; Noda, M.; Noto, H.; Origasa, H.; Osawa, H.; Taguchi, A.; Tanizawa, Y.; Tobe, K.; et al. Japanese Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes 2019. J. Diabetes Investig. 2020, 11, 1020–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itakura, A.; Shoji, S.; Shigeru, A.; Kotaro, F.; Junichi, H.; Hironobu, H.; Kamei, Y.; Eiji, K.; Shintaro, M.; Ryu, M.; et al. Guidelines for obstetrical practice in Japan: Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2020 edition. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2023, 49, 5–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassabi, M.; Esteghamati, A.; Halabchi, F.; Abedi-Yekta, A.H.; Mahdaviani, B.; Hassanmirzaie, B.; Hosseinpanah, F.; Valizadeh, M. Iranian National Clinical Practice Guideline for Exercise in Patients with Diabetes. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 19, e109021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valizadeh, M.; Hosseinpanah, F.; Tehrani, F.R.; Abdi, H.; Mehran, L.; Hadaegh, F.; Amouzegar, A.; Sarvghadi, F.; Azizi, F.; Iranian Endocrine Society Task Force. Iranian Endocrine Society Guidelines for Screening, Diagnosis, and Management of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 19, e107906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastasiou, E.; Farmakidis, G.; Gerede, A.; Goulis, D.G.; Koukkou, E.; Kourtis, A.; Mamopoulos, A.; Papadimitriou, K.; Papadopoulos, V.; Stefos, T. Clinical practice guidelines on diabetes mellitus and pregnancy: II. Gestational diabetes mellitus. Hormones 2020, 19, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, A.; Ranjan, P.; Vikram, N.K.; Kaur, D.; Balsalkar, G.; Malhotra, A.; Puri, M.; Batra, A.; Madan, J.; Tyagi, S.; et al. Executive summary of evidence and consensus-based clinical practice guideline for management of obesity and overweight in postpartum women: An AIIMS-DST initiative. Diabetes Metab. Syndr.-Clin. Res. Rev. 2022, 16, 102425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, M.; Asyali Biri, A.; Esim Büyükbayrak, E.; Daglar, H.K.; Ercan, F.; Gürsoy Erzincan, S.; Çorbacioglu Esmer, A.; Inan, C.; Kanit, H.; Kara, Ö.; et al. Guideline on pregnancy and diabetes by the society of specialists in perinatology (PUDER), Turkey. J. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 30, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, S.N.; Baqai, S.; Naheed, F.; Masood, Y.; Sikandar, R.; Chaudhri, R.; Yasmin, H.; Korejo, R.; Comm, G.D.M.G.; Soc Obstetricians, G. Guidelines for management of hyperglycemia in pregnancy (HIP) by Society of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists of Pakistan (SOGP). J. Diabetol. 2021, 12, 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Masood, S.N.; Shegem, N.; Baqai, S.; Suliman, M.; Alromaihi, D.; Sultan, M.; Salih, B.T.; Ram, U.; Ahmad, Z.; Aljufairi, Z.; et al. IDF-MENA region guidelines for management of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. J. Diabetol. 2021, 12, S3–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wender-Ozegowska, E.; Bomba-Opon, D.; Brazert, J.; Celewicz, Z.; Czajkowski, K.; Gutaj, P.; Malinowska-Polubiec, A.; Zawiejska, A.; Wielgos, M. Standards of Polish Society of Gynecologists and Obstetricians in management of women with diabetes. Ginekol. Pol. 2018, 89, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Public Health Qatar. National Clinical Guideline: The Diagnosis and Management of Diabetes in Pregnancy; Ministry of Public Health Qatar: Doha, Qatar, 2021.

- Schafer-Graf, U.M.; Gembruch, U.; Kainer, F.; Groten, T.; Hummel, S.; Hosli, I.; Grieshop, M.; Kaltheuner, M.; Buhrer, C.; Kautzky-Willer, A.; et al. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM)-Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. Guideline of the DDG and DGGG (S3 Level, AWMF Registry Number 057/008, February 2018). Geburtshilfe Und Frauenheilkd. 2018, 78, 1219–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martis, R.; Crowther, C.A.; Shepherd, E.; Alsweiler, J.; Downie, M.R.; Brown, J. Treatments for women with gestational diabetes mellitus: An overview of Cochrane systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 8, Cd012327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewage, S.S.; Wu, S.; Neelakantan, N.; Yoong, J. Systematic review of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of lifestyle interventions to improve clinical diabetes outcome measures in women with a history of GDM. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2020, 35, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retnakaran, M.; Viana, L.V.; Kramer, C.K. Lifestyle intervention for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in women with prior gestational diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2023, 25, 1196–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, J.M.; Kellett, J.E.; Balsells, M.; García-Patterson, A.; Hadar, E.; Solà, I.; Gich, I.; van der Beek, E.M.; Castañeda-Gutiérrez, E.; Heinonen, S.; et al. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Diet: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials Examining the Impact of Modified Dietary Interventions on Maternal Glucose Control and Neonatal Birth Weight. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 1346–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, M.R.K.; Lima, S.A.M.; da Silvia Mazeto, G.M.F.; Calderon, I.M.P.; Magalhães, C.G.; Ferraz, G.A.R.; Molina, A.C.; de Araújo Costa, R.A.; Nogueira, V.D.S.N.; Rudge, M.V.C. Efficacy of Vitamin D supplementation in gestational diabetes mellitus: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yefet, E.; Bar, L.; Izhaki, I.; Iskander, R.; Massalha, M.; Younis, J.S.; Nachum, Z. Effects of Probiotics on Glycemic Control and Metabolic Parameters in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Arcy, E.; Rayner, J.; Hodge, A.; Ross, L.J.; Schoenaker, D.A.J.M. The Role of Diet in the Prevention of Diabetes among Women with Prior Gestational Diabetes: A Systematic Review of Intervention and Observational Studies. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 120, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingena, C.F.; Arofikina, D.; Campbell, M.D.; Holmes, M.J.; Scott, E.M.; Zulyniak, M.A. Nutritional and Exercise-Focused Lifestyle Interventions and Glycemic Control in Women with Diabetes in Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Nutrients 2023, 15, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Guo, X.; Zhou, Y.; Cao, G. The Effects of Probiotics/Synbiotics on Glucose and Lipid Metabolism in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goveia, P.; Cañon-Montañez, W.; De Paula Santos, D.; Lopes, G.W.; Ma, R.C.W.; Duncan, B.B.; Ziegelman, P.K.; Schmidt, M.I. Lifestyle intervention for the prevention of diabetes in women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, G. Evidence Summary. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Antenatal Care. The JBI EBP Database. 2023. JBI-ES-524-4. Available online: https://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=jbi&AN=JBI17950 (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Lopes, G. Evidence Summary. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Management (Diet). The JBI EBP Database. 2023. JBI-ES-472-4. Available online: https://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=jbi&AN=JBI20937 (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Lopes, G. Evidence Summary. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Management (Education). The JBI EBP Database. 2023. JBI-ES-474-4. Available online: https://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=jbi&AN=JBI21004 (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Lopes, G. Evidence Summary. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Management (Exercise). The JBI EBP Database. 2023. JBI-ES-486-3. Available online: https://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=jbi&AN=JBI21005 (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Whitehorn, A. Evidence Summary. Gestational Diabetes: Management (Dietary Supplements). The JBI EBP Database. 2023. JBI-ES-629-2. Available online: https://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=jbi&AN=JBI21076 (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Moola, S. Evidence Summary. Gestational Diabetes: Management (Lifestyle Interventions). The JBI EBP Database. 2023. JBI-ES-647-2. Available online: https://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=jbi&AN=JBI21120 (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Aginga, C. Evidence Summary. Gestational Diabetes: Management (Omega-3 Fatty Acids). The JBI EBP Database. 2023. JBI-ES-657-2. Available online: https://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=jbi&AN=JBI21074 (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Aginga, C. Evidence Summary. Gestational Diabetes: Management (Probiotics). The JBI EBP Database. 2023. JBI-ES-652-2. Available online: https://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=jbi&AN=JBI21075 (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Wang, S.; Chen, Y.; Li, S.; Geng, X. Evidence summary for dietary management of gestational diabetes. Chin. J. Clin. Res. 2022, 35, 284–288. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, N.; Zhong, S.; Lu, Y.; Zhong, L.; Dong, L.; Zhai, Y. Evidence summary of diet management for patients with gestational diabetes mellitus. Chin. J. Nurs. Educ. 2021, 18, 1040–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Tan, X.; Xu, N.; Mi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xu, M. Evidence summary of exercise regimens for patients with gestational diabetes mellitus. Chin. J. Nurs. 2020, 55, 1514–1519. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yao, Q. Summary of best evidence for dietary nutrition management after cesarean section in pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus. J. Women Child. Health Guide 2022, 1, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Eleanor Scott, R.S. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus 2022. Available online: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/zh-cn/665 (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Durnwald, C. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Glucose Management and Maternal Prognosis 2022. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/zh-Hans/gestational-diabetes-mellitus-glucose-management-and-maternal-prognosis?search=Gestational%20diabetes%20mellitus%20Glucose%20management%20and%20maternal%20prognosis&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1 (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Durnwald, C. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Screening, Diagnosis, and Prevention 2022. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/zh-Hans/gestational-diabetes-mellitus-screening-diagnosis-and-prevention?search=Gestational%20diabetes%20mellitus%20Screening,%20diagnosis,%20and%20prevention%20&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~27&usage_type=default&display_rank=1 (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Abbas Raza, S. Gdm: Safes Recommendations and Action Plan-2017. JPMA-J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2018, 68, S1–S23. [Google Scholar]

- Benhalima, K.; Minschart, C.; Van Crombrugge, P.; Calewaert, P.; Verhaeghe, J.; Vandamme, S.; Theetaert, K.; Devlieger, R.; Pierssens, L.; Ryckeghem, H.; et al. The 2019 Flemish consensus on screening for overt diabetes in early pregnancy and screening for gestational diabetes mellitus. Acta Clin. Belg. 2020, 75, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, S.; McIntyre, H.D.; Tsoi, K.Y.; Kapur, A.; Ma, R.C.; Dias, S.; Okong, P.; Hod, M.; Poon, L.C.; Smith, G.N.; et al. Pregnancy as an opportunity to prevent type 2 diabetes mellitus: FIGO Best Practice Advice. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2023, 160 (Suppl. S1), 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Maternal and Child Health Association. Expert consensus on exercise during pregnancy (draft). Chin. J. Perinat. Med. 2021, 24, 641–645. [Google Scholar]

- Shawe, J.; Ceulemans, D.; Akhter, Z.; Neff, K.; Hart, K.; Heslehurst, N.; Štotl, I.; Agrawal, S.; Steegers-Theunissen, R.; Taheri, S.; et al. Pregnancy after bariatric surgery: Consensus recommendations for periconception, antenatal and postnatal care. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 1507–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.F.; Zhang, M.X.; Li, L.; Zhong, J.; Pan, X.H.; Zhao, X.Z.; Guo, N.F. Expert consensus study on recommendations of clinical nursing practice guidelines for gestational diabetes mellitus. Chin. Nurs. Res. 2020, 34, 4313–4318. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H. Guideline for the diagnosis and management of hyperglycemia in pregnancy (2022) [Part II]. Chin. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 57, 81–90. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/ChlQZXJpb2RpY2FsQ0hJTmV3UzIwMjMwMzIxEg56aGZjazIwMjIwMjAwMRoIbjN2Nm9hdHE%3D (accessed on 14 April 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).