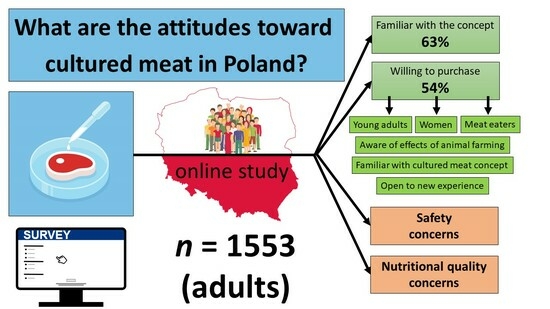

The Heat about Cultured Meat in Poland: A Cross-Sectional Acceptance Study

Highlights

- The perception of cultured meat in Poland before its introduction.

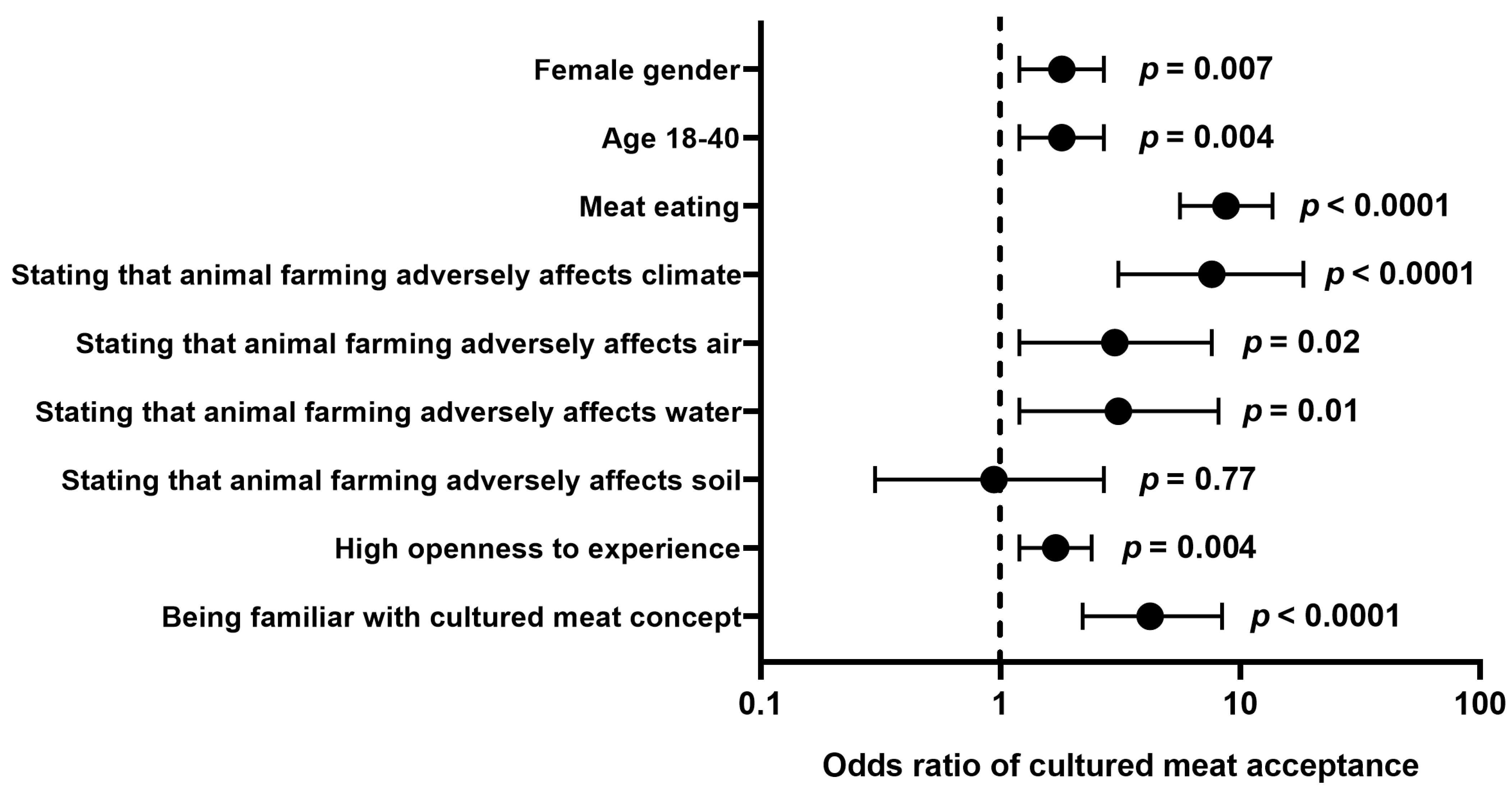

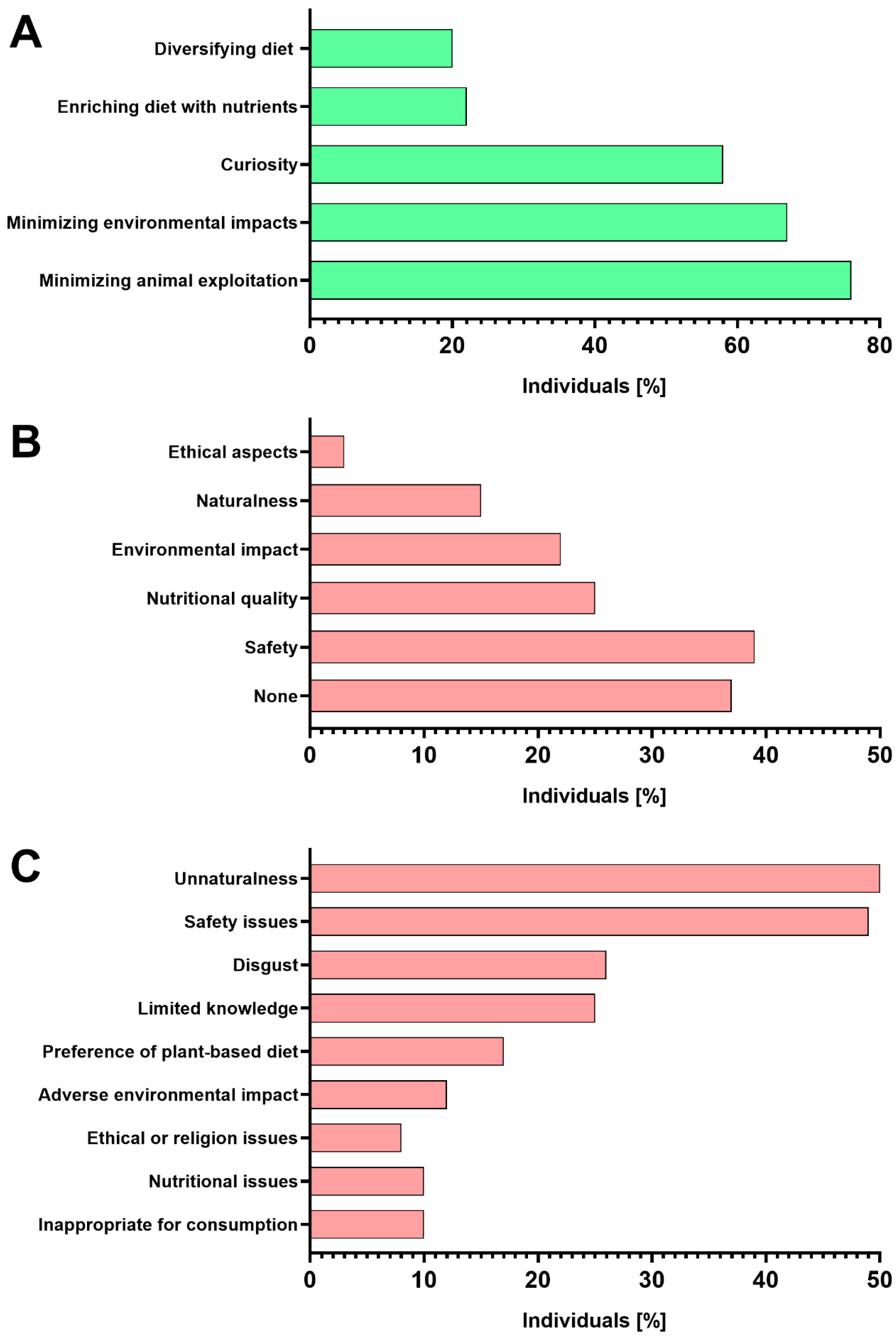

- Over half of the surveyed Poles expressed a desire to purchase cultured meat, especially women, young adults, meat-eaters, individuals open to new experiences, and those acknowledging the adverse effects of animal farming on the environment.

- Safety was the most frequent concern in those accepting and rejecting cultured meat.

- Campaigns and communication on cultured meat must address safety issues and transparently present the pros and cons of such products.

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey

- (i)

- familiarity of surveyed Poles with the concept of cultured meat;

- (ii)

- willingness to purchase cultured meat if it were to be commercialized in Poland;

- (iii)

- main reasons for acceptance or rejection of cultured meat;

- (iv)

- potential concerns regarding cultured meat.

- (i)

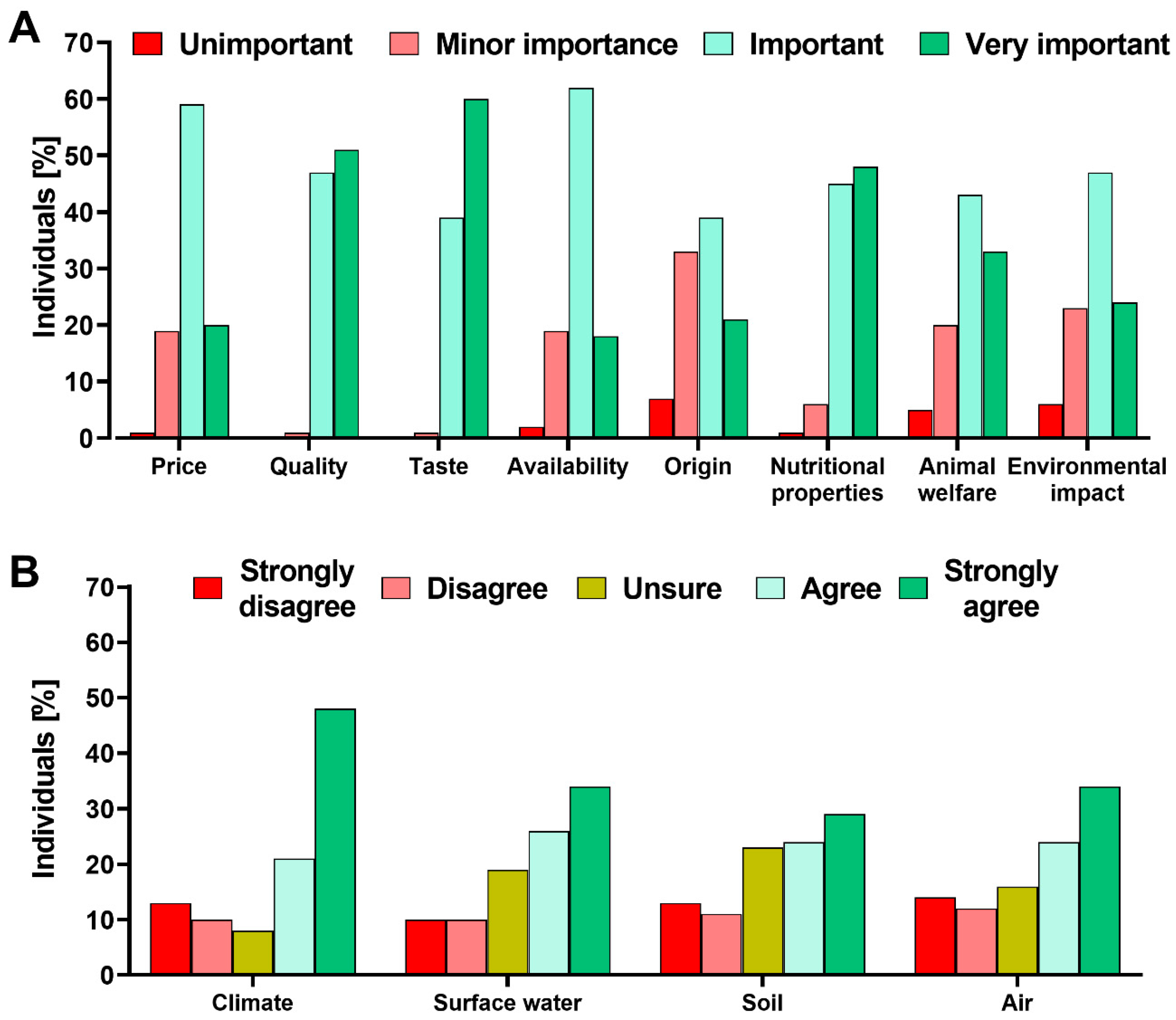

- factors influencing food purchases of surveyed individuals, including price, quality, taste, availability, origin, nutritional properties, animal welfare, and environmental impact;

- (ii)

- patterns of meat and dairy consumption as assessed by declaration of dietary patterns;

- (iii)

- awareness of adverse impacts of conventional meat production on the environment, including climate and quality of soil, water, and air;

- (iv)

- openness to experience as assessed by the validated Polish adaptation of the Ten-Item Personality Inventory [38,39], as this personality trait is known to be associated with food choices [40,41]. Openness to experience was categorized into low and high based on normative data for the employed inventory [38];

- (v)

- demographic characteristics, i.e., age, gender, level of education (none, primary, secondary, vocational, tertiary), place of residence (urban or rural area), and voivodeship (low and high GDP) [42].

2.2. Statistical Analyses and Calculations

3. Results

3.1. The Main Characteristics of the Studied Group

3.2. Factors Influencing Food Purchases

3.3. Attitudes toward Environmental Impacts of Animal Farming

3.4. Cultured Meat Acceptance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nuñez, I.A.; Ross, T.M. A Review of H5Nx Avian Influenza Viruses. Ther. Adv. Vaccines Immunother. 2019, 7, 2515135518821625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cordón, P.J.; Montoya, M.; Reis, A.L.; Dixon, L.K. African Swine Fever: A Re-Emerging Viral Disease Threatening the Global Pig Industry. Vet. J. 2018, 233, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, I.W. Animals and Mechanisms of Disease Transmission. In Emerging Zoonoses: A Worldwide Perspective; Fong, I.W., Ed.; Emerging Infectious Diseases of the 21st Century; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 15–38. ISBN 978-3-319-50890-0. [Google Scholar]

- Halabowski, D.; Rzymski, P. Taking a Lesson from the COVID-19 Pandemic: Preventing the Future Outbreaks of Viral Zoonoses through a Multi-Faceted Approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 757, 143723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulchandani, R.; Wang, Y.; Gilbert, M.; Van Boeckel, T.P. Global Trends in Antimicrobial Use in Food-Producing Animals: 2020 to 2030. PLoS Global Public Health 2023, 3, e0001305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.J.L.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Aguilar, G.R.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in 2019: A Systematic Analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippa, M.; Solazzo, E.; Guizzardi, D.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Tubiello, F.N.; Leip, A. Food Systems Are Responsible for a Third of Global Anthropogenic GHG Emissions. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machovina, B.; Feeley, K.J.; Ripple, W.J. Biodiversity Conservation: The Key Is Reducing Meat Consumption. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 536, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poore, J.; Nemecek, T. Reducing Food’s Environmental Impacts through Producers and Consumers. Science 2018, 360, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westhoek, H.; Lesschen, J.P.; Rood, T.; Wagner, S.; De Marco, A.; Murphy-Bokern, D.; Leip, A.; van Grinsven, H.; Sutton, M.A.; Oenema, O. Food Choices, Health and Environment: Effects of Cutting Europe’s Meat and Dairy Intake. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 26, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, P.; Brown, C.; Arneth, A.; Finnigan, J.; Rounsevell, M.D.A. Human Appropriation of Land for Food: The Role of Diet. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2016, 41, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Our World in Data Yearly Number of Animals Slaughtered for Meat. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/animals-slaughtered-for-meat (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Michel, F.; Hartmann, C.; Siegrist, M. Consumers’ Associations, Perceptions and Acceptance of Meat and Plant-Based Meat Alternatives. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 87, 104063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Huis, A.; Rumpold, B. Strategies to Convince Consumers to Eat Insects? A Review. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 110, 104927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.-H.; Yoon, J.W.; Kim, M.; Lee, H.J.; Jeong, J.; Ryu, M.; Jo, C.; Lee, C.-K. Muscle Stem Cell Isolation and in Vitro Culture for Meat Production: A Methodological Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 429–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubalek, S.; Post, M.J.; Moutsatsou, P. Towards Resource-Efficient and Cost-Efficient Cultured Meat. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 47, 100885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, N.R.; Xiang, N.; Kaplan, D.L. Plant-Based and Cell-Based Approaches to Meat Production. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinke, P.; Swartz, E.; Sanctorum, H.; van der Giesen, C.; Odegard, I. Ex-Ante Life Cycle Assessment of Commercial-Scale Cultivated Meat Production in 2030. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2023, 28, 234–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SFA Growing Our Food Future. Available online: https://www.sfa.gov.sg/docs/default-source/publication/annual-report/sfa-ar-2020-20212c7b8b52e3e84fd193c56d53f42fe607.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- FDA. FDA Completes Second Pre-Market Consultation for Human Food Made Using Animal Cell Culture Technology. 2023. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/cfsan-constituent-updates/fda-completes-second-pre-market-consultation-human-food-made-using-animal-cell-culture-technology (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- FDA. FDA Completes First Pre-Market Consultation for Human Food Made Using Animal Cell Culture Technology. 2023. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/cfsan-constituent-updates/fda-completes-first-pre-market-consultation-human-food-made-using-animal-cell-culture-technology (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- USDA. FSIS Directive 7800.1 FSIS Responsibilities in Establishments Producing Cell-Cultured Meat and Poultry Food Products. 2023. Available online: https://www.fsis.usda.gov/policy/fsis-directives/7800.1 (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- EFSA The Safety of Cell Culture-Derived Food—Ready for Scientific Evaluation|EFSA. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/news/safety-cell-culture-derived-food-ready-scientific-evaluation (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Cellular Agriculture Europe. Available online: https://www.cellularagriculture.eu/ (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Rzymski, P.; Królczyk, A. Attitudes toward Genetically Modified Organisms in Poland: To GMO or Not to GMO? Food Sec. 2016, 8, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C. Consumer Acceptance of Novel Food Technologies. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, D.; Rzymski, P. Chapter 13—Public Acceptance of GM Foods: A Global Perspective (1999–2019). In Policy Issues in Genetically Modified Crops; Singh, P., Borthakur, A., Singh, A.A., Kumar, A., Singh, K.K., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 293–315. ISBN 978-0-12-820780-2. [Google Scholar]

- Slade, P. If You Build It, Will They Eat It? Consumer Preferences for Plant-Based and Cultured Meat Burgers. Appetite 2018, 125, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Alvi, T.; Sameen, A.; Khan, S.; Blinov, A.V.; Nagdalian, A.A.; Mehdizadeh, M.; Adli, D.N.; Onwezen, M. Consumer Acceptance of Alternative Proteins: A Systematic Review of Current Alternative Protein Sources and Interventions Adapted to Increase Their Acceptability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Bouwman, E.P.; Reinders, M.J.; Dagevos, H. A Systematic Review on Consumer Acceptance of Alternative Proteins: Pulses, Algae, Insects, Plant-Based Meat Alternatives, and Cultured Meat. Appetite 2021, 159, 105058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Realini, C.E.; Ares, G.; Antúnez, L.; Brito, G.; Luzardo, S.; del Campo, M.; Saunders, C.; Farouk, M.M.; Montossi, F.M. Meat Insights: Uruguayan Consumers’ Mental Associations and Motives Underlying Consumption Changes. Meat Sci. 2022, 192, 108901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegrist, M.; Sütterlin, B.; Hartmann, C. Perceived Naturalness and Evoked Disgust Influence Acceptance of Cultured Meat. Meat Sci. 2018, 139, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzysztoszek, A. Poland Last EU Country to Make HPV Vaccine Free of Charge. Available online: https://www.euractiv.pl/section/zdrowie/news/poland-last-eu-country-to-make-hpv-vaccine-free-of-charge/ (accessed on 14 August 2023).

- Nitsch-Osuch, A.; Gołębiak, I.; Wyszkowska, D.; Rosińska, R.; Kargul, L.; Szuba, B.; Tyszko, P.; Brydak, L.B. Influenza Vaccination Coverage Among Polish Patients with Chronic Diseases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 968, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reczulska, A.; Tomaszewska, A.; Raciborski, F. Level of Acceptance of Mandatory Vaccination and Legal Sanctions for Refusing Mandatory Vaccination of Children. Vaccines 2022, 10, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobierajski, T.; Rzymski, P.; Wanke-Rytt, M. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Attitudes toward Vaccination: Representative Study of Polish Society. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sowa, P.; Kiszkiel, Ł.; Laskowski, P.P.; Alimowski, M.; Szczerbiński, Ł.; Paniczko, M.; Moniuszko-Malinowska, A.; Kamiński, K. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Poland—Multifactorial Impact Trajectories. Vaccines 2021, 9, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, S.D.; Rentfrow, P.J.; Swann, W.B. A Very Brief Measure of the Big-Five Personality Domains. J. Res. Personal. 2003, 37, 504–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokowska, A.; Słowińska, A.; Zbieg, A.; Sorokowski, P. Polska Adaptacja Testu Ten Item Personality Inventory (TIPI)—TIPI-PL—Wersja Standardowa i Internetowa. 2014. Available online: https://depot.ceon.pl/handle/123456789/5977 (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Ji, M.; Wong, I.A.; Eves, A.; Scarles, C. Food-Related Personality Traits and the Moderating Role of Novelty-Seeking in Food Satisfaction and Travel Outcomes. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, C.M.; Ceresa, A.; Buoli, M. The Association Between Personality Traits and Dietary Choices: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 1149–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUS Rachunki Regionalne. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/rachunki-narodowe/rachunki-regionalne/ (accessed on 7 September 2023).

- GUS Ludność. Stan i Struktura Ludności Oraz Ruch Naturalny w Przekroju Terytorialnym. Stan w Dniu 31 Grudnia. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/ludnosc/ludnosc/ludnosc-stan-i-struktura-ludnosci-oraz-ruch-naturalny-w-przekroju-terytorialnym-stan-w-dniu-31-grudnia,6,34.html (accessed on 31 August 2023).

- Cochran, W. Sampling Techniques, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Van Loo, E.J.; van Trijp, H.C.; Chen, J.; Bai, J. Will Cultured Meat Be Served on Chinese Tables? A Study of Consumer Attitudes and Intentions about Cultured Meat in China. Meat Sci. 2023, 197, 109081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grasso, A.C.; Hung, Y.; Olthof, M.R.; Verbeke, W.; Brouwer, I.A. Older Consumers’ Readiness to Accept Alternative, More Sustainable Protein Sources in the European Union. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewisch, L.; Riefler, P. Cultured Meat Acceptance for Global Food Security: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Directions. Agric. Food Econ. 2023, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, N.; Marquès, M.; Nadal, M.; Domingo, J.L. Meat Consumption: Which Are the Current Global Risks? A Review of Recent (2010–2020) Evidences. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djekic, I. Environmental Impact of Meat Industry—Current Status and Future Perspectives. Procedia Food Sci. 2015, 5, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chriki, S.; Payet, V.; Pflanzer, S.B.; Ellies-Oury, M.-P.; Liu, J.; Hocquette, É.; Rezende-de-Souza, J.H.; Hocquette, J.-F. Brazilian Consumers’ Attitudes towards So-Called “Cell-Based Meat”. Foods 2021, 10, 2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogueva, D.; Marinova, D. Cultured Meat and Australia’s Generation Z. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gousset, C.; Gregorio, E.; Marais, B.; Rusalen, A.; Chriki, S.; Hocquette, J.F.; Ellies-Oury, M.P. Perception of Cultured “Meat” by French Consumers According to Their Diet. Livest. Sci. 2022, 260, 104909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, C.; van Nek, L.; Rolland, N.C.M. European Markets for Cultured Meat: A Comparison of Germany and France. Foods 2020, 9, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröger, T.; Dupont, J.; Büsing, L.; Fiebelkorn, F. Acceptance of Insect-Based Food Products in Western Societies: A Systematic Review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, 759885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros-Baró, M.; Sánchez-Socarrás, V.; Santos-Pagès, M.; Bach-Faig, A.; Aguilar-Martínez, A. Consumers’ Acceptability and Perception of Edible Insects as an Emerging Protein Source. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrić, A.; Miličić, M.; Bojanić, M.; Obradović, V.; Šašić Zorić, L.; Petrović, M.; Gadjanski, I. Survey on Public Acceptance of Insects as Novel Food in a Non-EU Country: A Case Study of Serbia. J. Insects Food Feed 2023, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Egolf, A.; Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C. How People’s Food Disgust Sensitivity Shapes Their Eating and Food Behaviour. Appetite 2018, 127, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, C.; Siegrist, M. Becoming an Insectivore: Results of an Experiment. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 51, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, D.M.; Warrier, V.; Abu-Akel, A.; Allison, C.; Gajos, K.Z.; Reinecke, K.; Rentfrow, P.J.; Radecki, M.A.; Baron-Cohen, S. Sex and Age Differences in “Theory of Mind” across 57 Countries Using the English Version of the “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2022385119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, J.; Calheiros, M.M.; Oliveira, A.; Milfont, T.L. Why Are Women Less Likely to Support Animal Exploitation than Men? The Mediating Roles of Social Dominance Orientation and Empathy. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 129, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostol, L.; Rebega, O.L.; Miclea, M. Psychological and Socio-Demographic Predictors of Attitudes toward Animals. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 78, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, H.A. Gender Differences in Human-Animal Interactions: A Review. Anthrozoös 2007, 20, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, B.; Stewart, G.B.; Panzone, L.A.; Kyriazakis, I.; Frewer, L.J. A Systematic Review of Public Attitudes, Perceptions and Behaviours Towards Production Diseases Associated with Farm Animal Welfare. J. Agric. Env. Ethics 2016, 29, 455–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randler, C.; Adan, A.; Antofie, M.-M.; Arrona-Palacios, A.; Candido, M.; Boeve-de Pauw, J.; Chandrakar, P.; Demirhan, E.; Detsis, V.; Di Milia, L.; et al. Animal Welfare Attitudes: Effects of Gender and Diet in University Samples from 22 Countries. Animals 2021, 11, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, M.C.; Antonioli, F. Exploring Consumers’ Attitude towards Cultured Meat in Italy. Meat Sci. 2019, 150, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falowo, B.A.; Hosu, Y.S.; Idamokoro, E.M. Perspectives of Meat Eaters on the Consumption of Cultured Beef (in Vitro Production) From the Eastern Cape of South Africa. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 924396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolland, N.C.M.; Markus, C.R.; Post, M.J. The Effect of Information Content on Acceptance of Cultured Meat in a Tasting Context. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langfield, T. Neophobia. In Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science; Shackelford, T.K., Weekes-Shackelford, V.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 5362–5365. ISBN 978-3-319-19650-3. [Google Scholar]

- Resh, M.D. Covalent Lipid Modifications of Proteins. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, R431–R435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Hocquette, É.; Ellies-Oury, M.-P.; Chriki, S.; Hocquette, J.-F. Chinese Consumers’ Attitudes and Potential Acceptance toward Artificial Meat. Foods 2021, 10, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzymski, P.; Poniedziałek, B.; Fal, A. Willingness to Receive the Booster COVID-19 Vaccine Dose in Poland. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzymski, P.; Borkowski, L.; Drąg, M.; Flisiak, R.; Jemielity, J.; Krajewski, J.; Mastalerz-Migas, A.; Matyja, A.; Pyrć, K.; Simon, K.; et al. The Strategies to Support the COVID-19 Vaccination with Evidence-Based Communication and Tackling Misinformation. Vaccines 2021, 9, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobierajski, T.; Rzymski, P.; Wanke-Rytt, M. The Influence of Recommendation of Medical and Non-Medical Authorities on the Decision to Vaccinate against Influenza from a Social Vaccinology Perspective: Cross-Sectional, Representative Study of Polish Society. Vaccines 2023, 11, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poland: Trust in Public Institutions 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1193389/poland-trust-in-public-institutions/ (accessed on 24 September 2023).

- Michel, F.; Sanchez-Siles, L.M.; Siegrist, M. Predicting How Consumers Perceive the Naturalness of Snacks: The Usefulness of a Simple Index. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 94, 104295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomisto, H.L.; Allan, S.J.; Ellis, M.J. Prospective Life Cycle Assessment of a Bioprocess Design for Cultured Meat Production in Hollow Fiber Bioreactors. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 851, 158051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomisto, H.L.; Teixeira de Mattos, M.J. Environmental Impacts of Cultured Meat Production. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 6117–6123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, J.; Pierrehumbert, R. Climate Impacts of Cultured Meat and Beef Cattle. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Bahmid, N.A.; Karim, I.; Mehany, T.; Gvozdenko, A.A.; Blinov, A.V.; Nagdalian, A.A.; Arsyad, M.; Lorenzo, J.M. Cultured Meat: Processing, Packaging, Shelf Life, and Consumer Acceptance. LWT 2022, 172, 114192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obschonka, M.; Tavassoli, S.; Rentfrow, P.J.; Potter, J.; Gosling, S.D. Innovation and Inter-City Knowledge Spillovers: Social, Geographical, and Technological Connectedness and Psychological Openness. Res. Policy 2023, 52, 104849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, T.; Dowd, K. Susceptibility to anchoring effects: How openness-to-experience influences responses to anchoring cues. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2007, 2, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estell, M.; Hughes, J.; Grafenauer, S. Plant Protein and Plant-Based Meat Alternatives: Consumer and Nutrition Professional Attitudes and Perceptions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piochi, M.; Micheloni, M.; Torri, L. Effect of Informative Claims on the Attitude of Italian Consumers towards Cultured Meat and Relationship among Variables Used in an Explicit Approach. Food Res. Int. 2022, 151, 110881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin-Hi, N.; Reimer, M.; Schäfer, K.; Böttcher, J. Consumer Acceptance of Cultured Meat: An Empirical Analysis of the Role of Organizational Factors. J. Bus. Econ. 2023, 93, 707–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Khan, S.; Murid, M.; Asif, Z.; Oboturova, N.P.; Nagdalian, A.A.; Blinov, A.V.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Jafari, S.M. Marketing Strategies for Cultured Meat: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| General Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Gender, Female/Male/Other, % (n) | 78.3 (1217)/21.2 (329)/0.5 (7) |

| Age, mean (years ± SD) | 38.3 ± 13.4 |

| 18–25 years, % (n) | 15.6 (242) |

| 26–30 years, % (n) | 20 (310) |

| 31–40 years, % (n) | 30.5 (474) |

| 41–50 years, % (n) | 16.7 (259) |

| 51–60 years, % (n) | 7.8 (121) |

| >60 years, % (n) | 9.5 (147) |

| Place of residence | |

| Urban area/Rural area, % (n) | 85 (1314)/15 (239) |

| Voivodeship Gross Domestic Product | |

| Lower (<70 k)/Higher GDP (≥70 k), % (n) | 52 (803)/48 (750) |

| Education | |

| None, % (n) | 0.2 (3) |

| Primary, % (n) | 0.6 (9) |

| Vocational, % (n) | 1.7 (27) |

| Secondary, % (n) | 22.9 (356) |

| Tertiary, % (n) | 74.6 (1158) |

| Diet type | |

| Meat consumers, % (n) | 78.9 (1225) |

| Omnivores, % (n) | 49.4 (767) |

| Exclusion of dairy and eggs, % (n) | 1.2 (19) |

| Flexitarianism, % (n) | 28.3 (439) |

| Meat excluders, % (n) | 21.1 (328) |

| Ovo-vegetarianism, % (n) | 2.3 (36) |

| Lactoovovegetarianism, % (n) | 12.7 (197) |

| Lactovegetarianism, % (n) | 1.5 (23) |

| Veganism, % (n) | 4.6 (72) |

| Personality trait | |

| Openness to Experiences, mean (SD) | 5.1 (1.2) |

| High (≥5.38)/Low (<5.38), % (n) | 48 (745)/52 (808) |

| Parameter | Subgroups | Willing | Unwilling | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | ||||

| Age (years) | 18–40 | 39.5 (613) | 19.6 (304) | <0.00001 |

| >40 | 15.0 (233) | 15.1 (235) | ||

| Gender | Male | 13.4 (208) | 5.8 (92) | 0.001 |

| Female | 41 (636) | 28.5 (443) | ||

| Education | Non-tertiary | 12.7 (197) | 9.7 (151) | 0.056 |

| Tertiary | 41.5 (645) | 24.9 (386) | ||

| Inhabited area | Urban | 46.3 (719) | 29.2 (453) | 0.647 |

| Rural | 8.2 (127) | 5.5 (86) | ||

| Familiarity with the cultured meat concept | Yes | 50.2 (779) | 30.0 (462) | 0.0027 |

| No | 4.3 (66) | 4.4 (68) | ||

| Diet type | Meat eaters | 45.1 (700) | 25.8 (401) | 0.0002 |

| Meat excluders | 9.4 (146) | 8.9 (138) | ||

| Gross Domestic Product of inhabited region | Low (<70 k) | 27.1 (421) | 19.1 (296) | 0.069 |

| High (≥70 k) | 27.4 (425) | 15.7(243) | ||

| Attitudes toward conventional meat effects on the environment | Adversely affects climate | 48.2 (749) | 13.5 (210) | <0.00001 |

| Does not affect the climate | 3.0 (47) | 18.4 (286) | ||

| Adversely affects surface waters | 40.7 (632) | 13.1 (204) | <0.00001 | |

| Does not affect surface waters | 2.7 (42) | 15.8 (245) | ||

| Affects soil quality | 35.1 (545) | 11.5 (178) | <0.00001 | |

| Does not affect soil quality | 4.8 (74) | 17.3 (269) | ||

| Affects air quality | 40.1 (623) | 11.5 (178) | <0.00001 | |

| Does not affect air quality | 11.5 (178) | 17.3 (269) | ||

| Openness to experience | Low (<5.38) | 25.5 (396) | 20.0 (311) | 0.0001 |

| High (≥5.38) | 30.0 (450) | 14.7 (228) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sikora, D.; Rzymski, P. The Heat about Cultured Meat in Poland: A Cross-Sectional Acceptance Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4649. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15214649

Sikora D, Rzymski P. The Heat about Cultured Meat in Poland: A Cross-Sectional Acceptance Study. Nutrients. 2023; 15(21):4649. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15214649

Chicago/Turabian StyleSikora, Dominika, and Piotr Rzymski. 2023. "The Heat about Cultured Meat in Poland: A Cross-Sectional Acceptance Study" Nutrients 15, no. 21: 4649. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15214649

APA StyleSikora, D., & Rzymski, P. (2023). The Heat about Cultured Meat in Poland: A Cross-Sectional Acceptance Study. Nutrients, 15(21), 4649. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15214649