Enhancing Chronic-Disease Education through Integrated Medical and Social Care: Exploring the Beneficial Role of a Community Teaching Kitchen in Oregon

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview

2.2. Setting

2.3. Teaching Kitchen Referrals

2.4. Providence Community Teaching Kitchen Design and Evolution

2.5. Addressing Unmet Social Needs

2.6. Study Population

2.7. Data Measures and Subpopulation Analyses

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Population Description (Table 2)

| Overall, N = 3077 | Highly Engaged, N = 959 | Engaged, N = 2118 | p-Value 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insurance Type, N (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Commercial/Other | 1049 (35.2) | 249 (26.6) | 800 (39.1) | |

| Medicare | 1033 (34.7) | 375 (39.1) | 658 (32.2) | |

| Medicaid | 828 (27.8) | 283 (30.4) | 545 (26.7) | |

| Dual Eligible | 69 (2.3) | 28 (3.0) | 41 (2.0) | |

| Missing | 98 | 24 | 74 | |

| Gender/Sex, N (%) | 0.2 | |||

| Female | 2038 (66.2) | 656 (68.4) | 1382 (65.2) | |

| Male | 1037 (33.7) | 302 (31.5) | 735 (34.7) | |

| Other | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Mean Age (SD) | 51.4 (16.2) | 52.3 (15.6) | 50.9 (16.4) | 0.013 |

| Age Group, N (%) | 0.075 | |||

| 18–39 | 812 (26.3) | 224 (23.4) | 588 (27.8) | |

| 40–49 | 545 (17.7) | 164 (17.1) | 381 (18.0) | |

| 50–59 | 645 (21.0) | 216 (22.5) | 429 (20.3) | |

| 60–64 | 355 (11.5) | 118 (12.3) | 237 (11.2) | |

| 65+ | 720 (23.4) | 237 (24.7) | 483 (22.8) | |

| Race/Ethnicity, N (%) | 0.009 | |||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 2357 (79.8) | 743 (80.8) | 1614 (79.4) | |

| Other Race, Non-Hispanic | 173 (5.9) | 63 (6.8) | 110 (5.4) | |

| Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, Non-Hispanic | 102 (3.5) | 23 (2.5) | 79 (3.9) | |

| Black or African American, Non-Hispanic | 78 (2.6) | 31 (3.4) | 47 (2.3) | |

| Hispanic or Latino, of any race | 244 (8.3) | 60 (6.5) | 184 (9.0) | |

| Missing | 123 | 39 | 84 | |

| Social Needs, N (%) | ||||

| Food Insecurity | 608 (19.8) | 315 (32.8) | 293 (13.8) | <0.0001 |

| Housing | 86 (2.8) | 45 (4.7) | 41 (1.9) | <0.0001 |

| Transportation | 112 (3.6) | 55 (5.7) | 57 (2.7) | <0.0001 |

| Utilities | 78 (2.5) | 36 (3.8) | 42 (2.0) | 0.006 |

| Comorbidities, N (%) | ||||

| Obesity | 436 (14.2) | 154 (16.1) | 282 (13.3) | 0.049 |

| Diabetes mellitus with/without complication | 401 (13.0) | 120 (12.5) | 281 (13.3) | 0.6 |

| Disorders of lipid metabolism | 368 (12.0) | 112 (11.7) | 256 (12.1) | 0.79 |

| Hypertension | 365 (11.9) | 117 (12.2) | 248 (11.7) | 0.74 |

| Depressive disorders | 281 (9.1) | 109 (11.4) | 172 (8.1) | 0.005 |

| Osteoarthritis | 222 (7.2) | 80 (8.3) | 142 (6.7) | 0.12 |

| Heart failure | 145 (4.7) | 45 (4.7) | 100 (4.7) | 1 |

| Coronary atherosclerosis and other heart disease | 141 (4.6) | 46 (4.8) | 95 (4.5) | 0.77 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 130 (4.2) | 44 (4.6) | 86 (4.1) | 0.56 |

| 3 or more chronic conditions | 322 (10.5) | 112 (11.7) | 210 (9.9) | 0.16 |

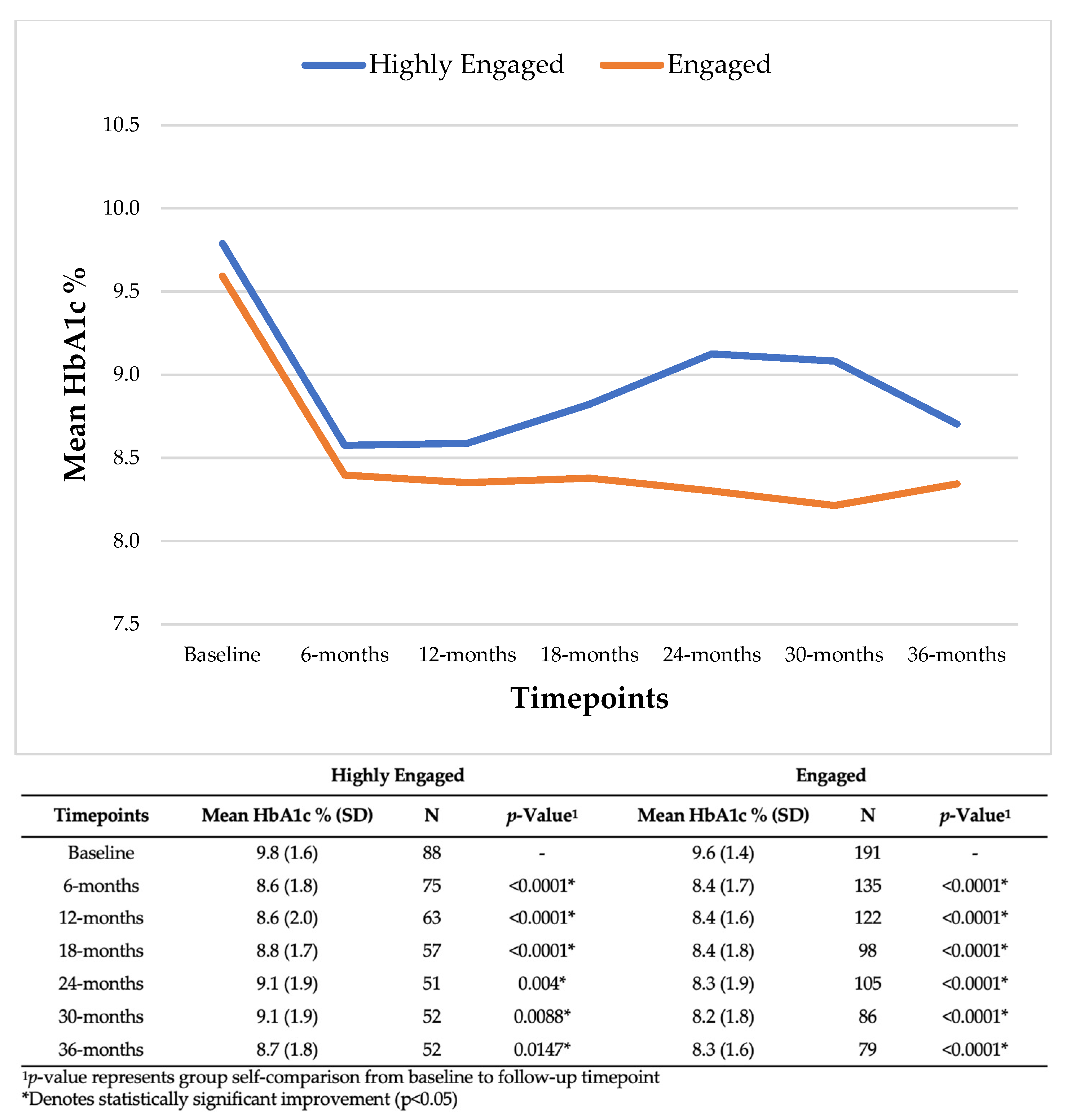

3.2. Clinical Measures

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McPhail, S.M. Multimorbidity in chronic disease: Impact on health care resources and costs. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2016, 9, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajat, C.; Stein, E. The global burden of multiple chronic conditions: A narrative review. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 12, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Xu, Y.; Pan, X.; Xu, J.; Ding, Y.; Sun, X.; Song, X.; Ren, Y.; Shan, P.F. Global, regional, and national burden and trend of diabetes in 195 countries and territories: An analysis from 1990 to 2025. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naghavi, M.; Wang, H.; Lozano, R.; Davis, A.; Liang, X.; Zhou, M.; Vollset, S.E.; Abbasoglu Ozgoren, A.; Abdalla, S.; Abd-Allah, F.; et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015, 385, 117–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikbov, B.; Purcell, C.A.; Levey, A.S.; Smith, M.; Abdoli, A.; Abebe, M.; Adebayo, O.M.; Afarideh, M.; Agarwal, S.K.; Agudelo-Botero, M.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2020, 395, 709–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, C.K.; Barnard, R.J. Effects of exercise and diet on chronic disease. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 98, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimokoti, R.W.; Millen, B.E. Nutrition for the Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 100, 1185–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Who, J.; Consultation, F.E. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. World Health Organ Tech. Rep. Ser. 2003, 916, 1–149. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, S.A. Core indicators of nutritional state for difficult-to-sample populations. J. Nutr. 1990, 120 (Suppl. S11), 1559–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seligman, H.K.; Laraia, B.A.; Kushel, M.B. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piontak, J.R.; Schulman, M.D. Food insecurity in rural America. Contexts 2014, 13, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swavely, D.; Whyte, V.; Steiner, J.F.; Freeman, S.L. Complexities of addressing food insecurity in an urban population. Popul. Health Manag. 2019, 22, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowda, C.; Hadley, C.; Aiello, A.E. The association between food insecurity and inflammation in the US adult population. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 1579–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laraia, B.A. Food insecurity and chronic disease. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decker, D.; Flynn, M. Food Insecurity and Chronic Disease: Addressing Food Access as a Healthcare Issue. R. I. Med. J. 2018, 101, 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bengle, R.; Sinnett, S.; Johnson, T.; Johnson, M.A.; Brown, A.; Lee, J.S. Food insecurity is associated with cost-related medication non-adherence in community-dwelling, low-income older adults in Georgia. J. Nutr. Elder. 2010, 29, 170–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charkhchi, P.; Fazeli Dehkordy, S.; Carlos, R.C. Housing and Food Insecurity, Care Access, and Health Status Among the Chronically Ill: An Analysis of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. J. Gen. Intern Med. 2018, 33, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanumihardjo, J.P.; Gunter, K.E.; Peek, M.E. As They Take On Food Insecurity, Community-Based Health Care Organizations Have Found Four Strategies That Work. Health Aff. Forefr. 2021. Available online: https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/they-take-food-insecurity-community-based-health-care-organizations-have-found-four (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- Eisenberg, D.M.; Righter, A.C.; Matthews, B.; Zhang, W.; Willett, W.C.; Massa, J. Feasibility Pilot Study of a Teaching Kitchen and Self-Care Curriculum in a Workplace Setting. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2019, 13, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, D.M.; Pacheco, L.S.; McClure, A.C.; McWhorter, J.W.; Janisch, K.; Massa, J. Perspective: Teaching Kitchens: Conceptual Origins, Applications and Potential for Impact within Food Is Medicine Research. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.V.; McWhorter, J.W.; Chow, J.; Danho, M.P.; Weston, S.R.; Chavez, F.; Moore, L.S.; Almohamad, M.; Gonzalez, J.; Liew, E.; et al. Impact of a Virtual Culinary Medicine Curriculum on Biometric Outcomes, Dietary Habits, and Related Psychosocial Factors among Patients with Diabetes Participating in a Food Prescription Program. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musicus, A.A.; Vercammen, K.A.; Fulay, A.P.; Moran, A.J.; Burg, T.; Allen, L.; Maffeo, D.; Berger, A.; Rimm, E.B. Implementation of a Rooftop Farm Integrated with a Teaching Kitchen and Preventive Food Pantry in a Hospital Setting. Am. J. Public Health 2019, 109, 1119–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polak, R.; Phillips, E.M.; Nordgren, J.; La Puma, J.; La Barba, J.; Cucuzzella, M.; Graham, R.; Harlan, T.S.; Burg, T.; Eisenberg, D. Health-related Culinary Education: A Summary of Representative Emerging Programs for Health Professionals and Patients. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 2016, 5, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Providence Milwaukie Hospital. 2019 Community Health Needs Assessment Executive Summary. Available online: https://www.providence.org/-/media/Project/psjh/providence/socal/Files/about/community-benefit/pdfs/milwaukie2019chna.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- Tanumihardjo, J.P.; Davis, H.; Christensen, J.; Smith, R.A.; Kauffman-Smith, S.; Gunter, K.E. Hospital-Based, Community Teaching Kitchen Integrates Diabetes Education, Culinary Medicine, and Food Assistance: Case Study During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Gen. Intern Med. 2023, 38, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, S.; Gronowski, B.; Jones, K.; Smith, R.; Vartanian, K.; Wright, B. Evaluation of an integrated intervention to address clinical care social needs among patients with Type 2 diabetes. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 38, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanumihardjo, J.P.; Gunter, K.E.; Peek, M.E. Integrating Technology and Human Capital to Address Social Needs: Lessons to Promote Health Equity in Diabetes Care. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2021, 32, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaseem, A.; Wilt, T.J.; Kansagara, D.; Horwitch, C.; Barry, M.J.; Forciea, M.A.; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Hemoglobin A1c Targets for Glycemic Control with Pharmacologic Therapy for Nonpregnant Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Guidance Statement Update from the American College of Physicians. Ann. Intern Med. 2018, 168, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flack, J.M.; Adekola, B. Blood pressure and the new ACC/AHA hypertension guidelines. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 30, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, S.M.; Stone, N.J.; Bailey, A.L.; Beam, C.; Birtcher, K.K.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Braun, L.T.; de Ferranti, S.; Faiella-Tommasino, J.; Forman, D.E.; et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 3168–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, D.H.; Yockey, S.R. Weight Loss and Improvement in Comorbidity: Differences at 5%, 10%, 15%, and Over. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2017, 6, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magallanes, E.; Sen, A.; Siler, M.; Albin, J. Nutrition from the kitchen: Culinary medicine impacts students’ counseling confidence. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Riccardi, D.; Pflanzer, S.; Redwine, L.S.; Gray, H.L.; Carson, T.L.; McDowell, M.; Thompson, Z.; Hubbard, J.J.; Pabbathi, S. Survivors Overcoming and Achieving Resiliency (SOAR): Mindful Eating Practice for Breast Cancer Survivors in a Virtual Teaching Kitchen. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monlezun, D.J.; Kasprowicz, E.; Tosh, K.W.; Nix, J.; Urday, P.; Tice, D.; Sarris, L.; Harlan, T.S. Medical school-based teaching kitchen improves HbA1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol for patients with type 2 diabetes: Results from a novel randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2015, 109, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommer, S.; Pelletier, A.; Roche, A.; Klein, L.; Dawes, K.; Hellerstein, S. Evaluation of dietary habits and cooking confidence using virtual teaching kitchens for perimenopausal women. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, M.; Luna-Gierke, R.E.; Carree, T.; Gutierrez, M.; Yuan, X.; Dasgupta, S. Racial Differences in Social Determinants of Health and Outcomes Among Hispanic/Latino Persons with HIV-United States, 2015–2020. J. Racial. Ethn. Health Disparities 2023, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahre, M.; VanEenwyk, J.; Siegel, P.; Njai, R. Housing Insecurity and the Association with Health Outcomes and Unhealthy Behaviors, Washington State, 2011. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2015, 12, E109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stratton, I.M.; Adler, A.I.; Neil, H.A.; Matthews, D.R.; Manley, S.E.; Cull, C.A.; Hadden, D.; Turner, R.C.; Holman, R.R. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): Prospective observational study. BMJ 2000, 321, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lage, M.J.; Boye, K.S. The relationship between HbA1c reduction and healthcare costs among patients with type 2 diabetes: Evidence from a U.S. claims database. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2020, 36, 1441–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reboldi, G.; Gentile, G.; Angeli, F.; Ambrosio, G.; Mancia, G.; Verdecchia, P. Effects of intensive blood pressure reduction on myocardial infarction and stroke in diabetes: A meta-analysis in 73,913 patients. J. Hypertens 2011, 29, 1253–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apolzan, J.W.; Venditti, E.M.; Edelstein, S.L.; Knowler, W.C.; Dabelea, D.; Boyko, E.J.; Pi-Sunyer, X.; Kalyani, R.R.; Franks, P.W.; Srikanthan, P.; et al. Long-Term Weight Loss with Metformin or Lifestyle Intervention in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Ann. Intern Med. 2019, 170, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bangalore, S.; Fayyad, R.; Kastelein, J.J.; Laskey, R.; Amarenco, P.; DeMicco, D.A.; Waters, D.D. 2013 Cholesterol Guidelines Revisited: Percent LDL Cholesterol Reduction or Attained LDL Cholesterol Level or Both for Prognosis? Am. J. Med. 2016, 129, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Integrating Social Care into the Delivery of Health Care: Moving Upstream to Improve the Nation’s Health; Academies Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Implementing High-Quality Primary Care: Rebuilding the Foundation of Health Care; Academies Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Virani, S.S.; Aspry, K.; Dixon, D.L.; Ferdinand, K.C.; Heidenreich, P.A.; Jackson, E.J.; Jacobson, T.A.; McAlister, J.L.; Neff, D.R.; Gulati, M.; et al. The importance of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol measurement and control as performance measures: A joint Clinical Perspective from the National Lipid Association and the American Society for Preventive Cardiology. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2023, 17, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, D.E.; Thomas, R.J.; Bhalla, V.; Commodore-Mensah, Y.; Heidenreich, P.A.; Kolte, D.; Muntner, P.; Smith, S.C.; Spertus, J.A.; Windle, J.R.; et al. 2019 AHA/ACC Clinical Performance and Quality Measures for Adults with High Blood Pressure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 2661–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Year | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTK Staff Member (FTE) | Patient Navigator (1.0 FTE) | Patient Navigator (1.5 FTE) | Patient Navigator (1.5 FTE) | Patient Navigator (1.5 FTE) | Patient Navigator (1.5 FTE) | Patient Navigator (1.5 FTE) | Patient Navigator (2.0 FTE) |

| Registered Dietitian (1.0 FTE) | Registered Dietitian (2.0 FTE) | Registered Dietitian (2.0 FTE) | Registered Dietitian (2.0 FTE) | Registered Dietitian (1.5 FTE) | Registered Dietitian (1.5 FTE) | Registered Dietitian (2.5 FTE) | |

| Physician Champion | Physician Champion | Physician Champion | Physician Champion | Physician Champion | Physician Champion | Physician Champion | |

| Program Manager (1.0 FTE) | Program Manager (1.0 FTE) | Program Manager (1.0 FTE) | Program Manager (1.0 FTE) | Program Manager (1.0 FTE) | |||

| Cooking Instructors (0.5 FTE) | Cooking Instructors (0.25 FTE) | Cooking Instructors (0.25 FTE) | Cooking Instructors (0.25 FTE) | Cooking Instructors (0.5 FTE) | |||

| Videographer (0.25 FTE) | Videographer (0.75 FTE) | Videographer (0.75 FTE) | |||||

| Gardening Coordinator (0.5 FTE) | |||||||

| Total FTE | 2.0 | 3.5 | 5.0 | 4.75 | 4.5 | 5.0 | 7.25 |

| Highly Engaged | Engaged | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timepoint | Mean SBP (SD) | Mean DBP (SD) | N | p-Value 1 | Mean SBP (SD) | Mean DBP (SD) | N | p-Value 1 |

| Baseline | 141.4 (10.2) | 86.8 (6.0) | 152 | - | 142.4 (11.0) | 87.5 (6.2) | 338 | - |

| 6 months | 134.2 (15.7) | 81.2 (8.8) | 107 | <0.0001 * | 136.2 (14.0) | 82.2 (9.1) | 222 | <0.0001 * |

| 12 months | 134.2 (12.8) | 80.6 (8.3) | 98 | <0.0001 * | 135.4 (15.1) | 82.5 (9.9) | 207 | <0.0001 * |

| 18 months | 134.1 (14.4) | 79.7 (9.5) | 84 | <0.0001 * | 134.3 (14.8) | 81.6 (8.7) | 178 | <0.0001 * |

| 24 months | 132.0 (14.0) | 78.9 (8.9) | 79 | <0.0001 * | 135.5 (14.7) | 81.4 (9.2) | 146 | <0.0001 * |

| 30 months | 131.2 (12.6) | 79.3 (9.6) | 78 | <0.0001 * | 134.4 (14.6) | 80.7 (8.8) | 145 | <0.0001 * |

| 36 months | 132.2 (12.9) | 79.4 (6.9) | 66 | <0.0001 * | 135.0 (16.0) | 81.4 (8.9) | 126 | <0.0001 * |

| Highly Engaged | Engaged | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparisons | Mean Change (%) | SD | N | p-Value | Mean Change (%) | SD | N | p-Value |

| Baseline to 6 months | −0.83 | 5.30 | 707 | 0.0012 * | −0.36 | 5.55 | 1299 | 0.0431 * |

| Baseline to 12 months | −0.90 | 6.37 | 606 | 0.0001 * | −0.27 | 6.75 | 1162 | 0.0842 |

| Baseline to 18 months | −1.03 | 7.34 | 509 | <0.0001 * | −0.24 | 8.00 | 957 | 0.0183 * |

| Baseline to 24 months | −1.22 | 8.30 | 474 | <0.0001 * | −0.30 | 8.77 | 909 | 0.0021 * |

| Baseline to 30 months | −1.46 | 8.88 | 433 | <0.0001 * | −0.35 | 9.09 | 854 | 0.0003 * |

| Baseline to 36 months | −1.25 | 9.62 | 390 | <0.0001 * | −0.16 | 9.64 | 774 | 0.0774 |

| Highly Engaged | Engaged | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timepoint | Mean LDL (SD) | N | p-Value 1 | Mean LDL (SD) | N | p-Value 1 |

| Baseline | 133.5 (28.5) | 120 | - | 134.8 (25.3) | 300 | - |

| 12 months | 120.2 (34.6) | 46 | <0.0001 * | 121.7 (29.0) | 109 | <0.0001 * |

| 24 months | 106.1 (32.5) | 36 | <0.0001 * | 129.6 (32.9) | 88 | <0.0001 * |

| 36 months | 112.5 (37.4) | 32 | <0.0001 * | 119.5 (32.2) | 78 | <0.0001 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tanumihardjo, J.P.; Davis, H.; Zhu, M.; On, H.; Guillory, K.K.; Christensen, J. Enhancing Chronic-Disease Education through Integrated Medical and Social Care: Exploring the Beneficial Role of a Community Teaching Kitchen in Oregon. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4368. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15204368

Tanumihardjo JP, Davis H, Zhu M, On H, Guillory KK, Christensen J. Enhancing Chronic-Disease Education through Integrated Medical and Social Care: Exploring the Beneficial Role of a Community Teaching Kitchen in Oregon. Nutrients. 2023; 15(20):4368. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15204368

Chicago/Turabian StyleTanumihardjo, Jacob P., Heidi Davis, Mengqi Zhu, Helen On, Kayla K. Guillory, and Jill Christensen. 2023. "Enhancing Chronic-Disease Education through Integrated Medical and Social Care: Exploring the Beneficial Role of a Community Teaching Kitchen in Oregon" Nutrients 15, no. 20: 4368. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15204368

APA StyleTanumihardjo, J. P., Davis, H., Zhu, M., On, H., Guillory, K. K., & Christensen, J. (2023). Enhancing Chronic-Disease Education through Integrated Medical and Social Care: Exploring the Beneficial Role of a Community Teaching Kitchen in Oregon. Nutrients, 15(20), 4368. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15204368