General Practitioners’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Dietary Advice for Weight Control in Their Overweight Patients: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy and Article Selection

- Location/Population: international/worldwide

- Target age group: Adults (aged 18 years and above)

- Primary research studies

- Papers published from 1 January 2017 to search date (31 of July 2022)

- Published in English

- Full text available

- All types of study: surveys, trials, cohorts, interviews, focus groups.

- Advice for children and adolescents (<18 years old) or pregnancy

- Nutrition problems other than being overweight/obese

- Articles focused on health advice other than nutrition (e.g., exercise, sleep, etc.)

- Editorials, commentaries, theses, book chapters, reviews, systematic reviews

- Grey literature

2.3. Data Charting Process and Synthesis

3. Results

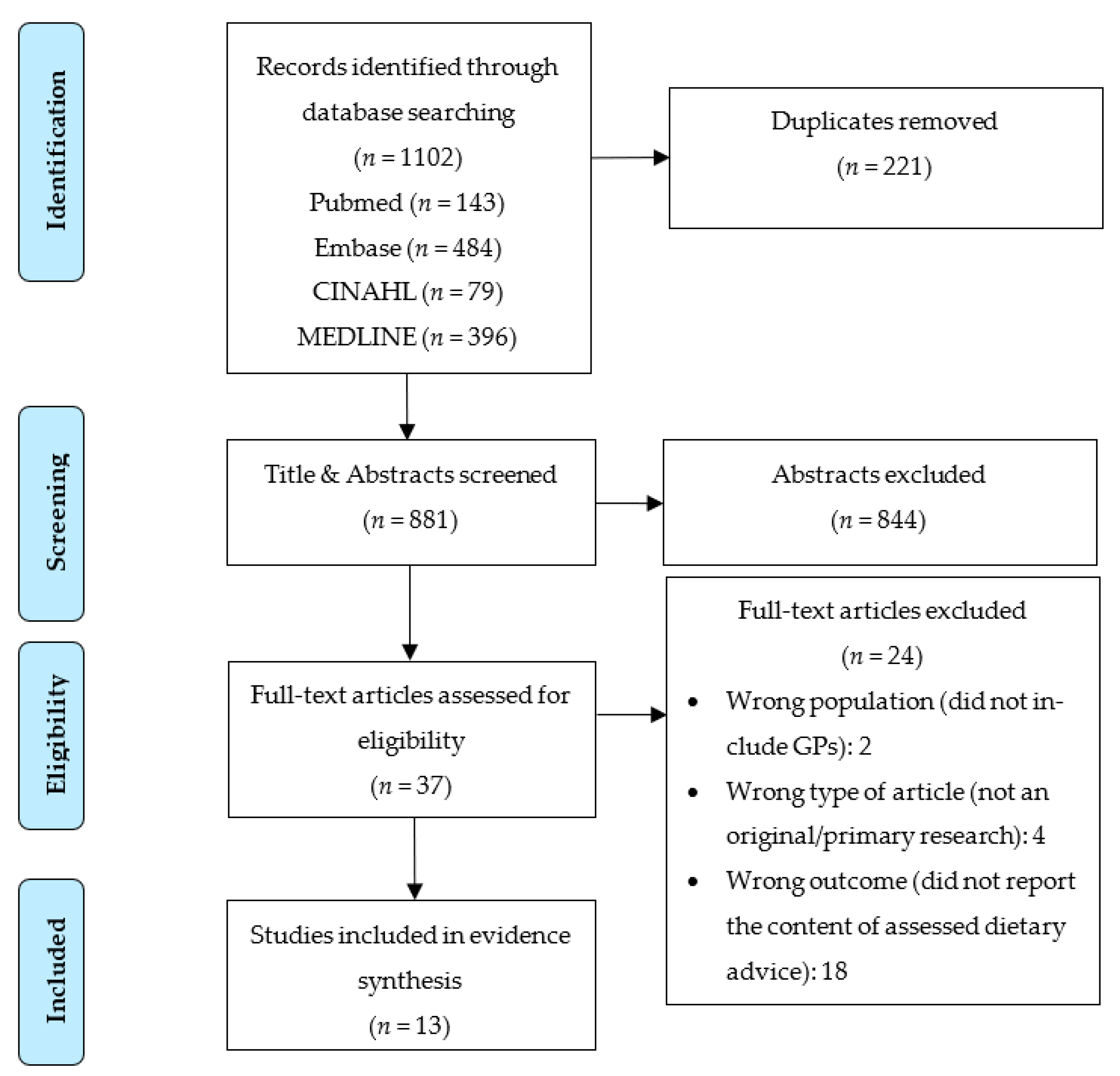

3.1. Selection of Sources of Evidence

3.2. Characteristics of Sources of Evidence

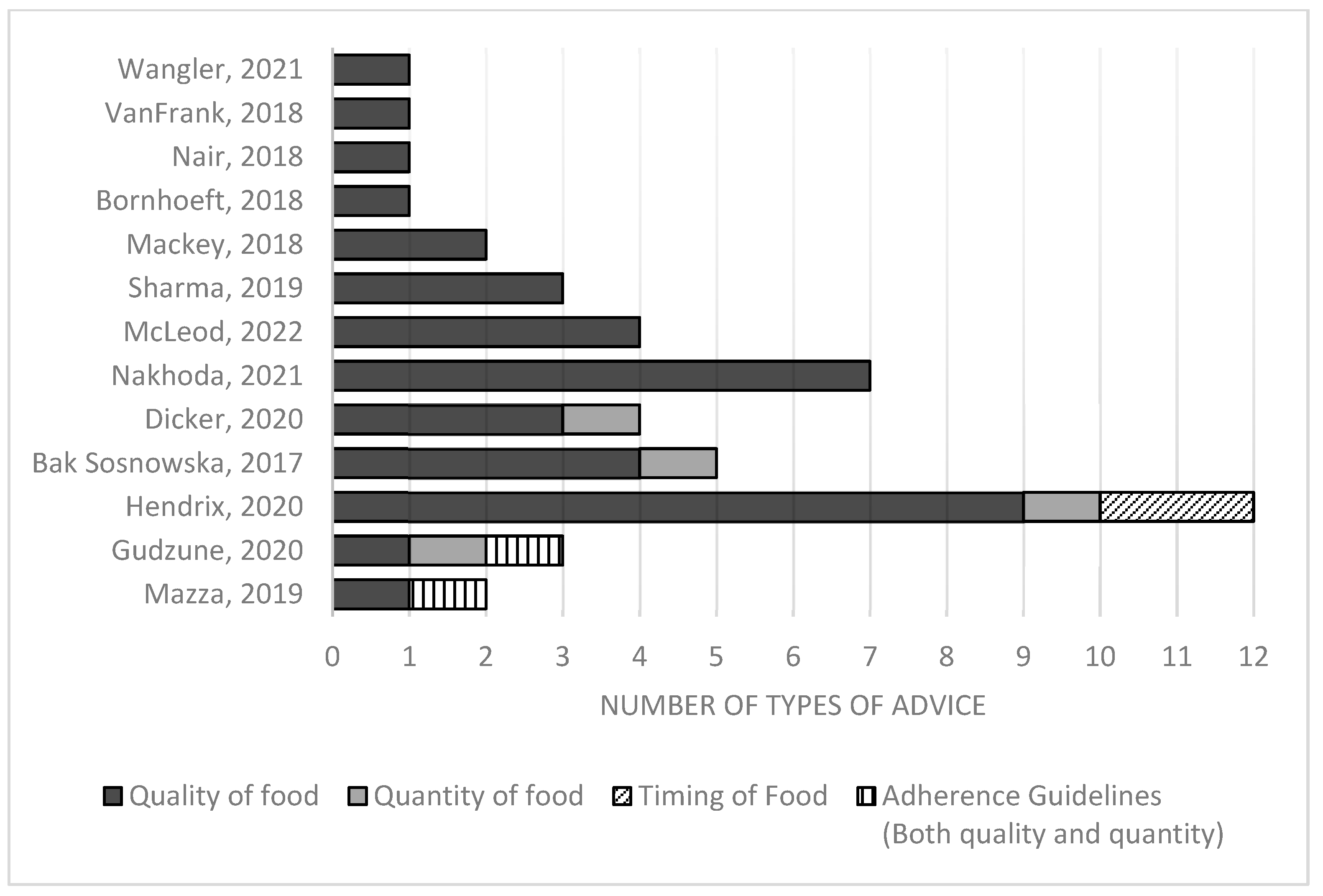

3.3. Content of Dietary Advice Reported

3.3.1. Knowledge of GPs

3.3.2. Attitudes of GPs

3.3.3. Practices of GPs

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- Cornier, M.A. A review of current guidelines for the treatment of obesity. Am. J. Manag. Care 2022, 28 (Suppl. S15), S288–S296. Available online: https://www.ajmc.com/view/review-of-current-guidelines-for-the-treatment-of-obesity (accessed on 23 February 2023). [PubMed]

- O’Connor, S.G.; Boyd, P.; Bailey, C.P.; Shams-White, M.M.; Agurs-Collins, T.; Hall, K.; Reedy, J.; Sauter, E.R.; Czajkowski, S.M. Perspective: Time-Restricted Eating Compared with Caloric Restriction: Potential Facilitators and Barriers of Long-Term Weight Loss Maintenance. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulloo, A.G. Physiology of weight regain: Lessons from the classic Minnesota Starvation Experiment on human body composition regulation. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trexler, E.T.; Smith-Ryan, A.E.; Norton, L.E. Metabolic adaptation to weight loss: Implications for the athlete. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2014, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreiro, A.L.; Dhillon, J.; Gordon, S.; Higgins, K.A.; Jacobs, A.G.; McArthur, B.M.; Redan, B.W.; Rivera, R.L.; Schmidt, L.R.; Mattes, R.D. The Macronutrients, Appetite, and Energy Intake. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2016, 36, 73–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaulet, M.; Gómez-Abellán, P.; Alburquerque-Béjar, J.J.; Lee, Y.C.; Ordovás, J.M.; Scheer, F.A.J.L. Timing of food intake predicts weight loss effectiveness. Int. J. Obes. 2013, 37, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, K.C.; Olofsson, C.; Cunha, J.P.M.C.M.; Roberts, F.; Catrina, S.B.; Fex, M.; Ekberg, N.R.; Spégel, P. The impact of macronutrient composition on metabolic regulation: An Islet-Centric view. Acta Physiol. 2022, 236, e13884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, M.E.; Cohen, J.B.; Ard, J.D.; Egan, B.M.; Hall, J.E.; Lavie, C.J.; Ma, J.; Ndumele, C.E.; Schauer, P.R.; Shimbo, D. Weight-Loss Strategies for Prevention and Treatment of Hypertension: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension 2021, 78, e38–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Corey, K.E.; Lim, J.K. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Lifestyle Modification Using Diet and Exercise to Achieve Weight Loss in the Management of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Expert Review. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 912–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diabetes Australia. Position Statement: Type 2 Diabetes Remission; Diabetes Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix, J.K.; Aikens, J.E.; Saslow, L.R. Dietary weight loss strategies for self and patients: A cross-sectional survey of female physicians. Obes. Med. 2020, 17, 100158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracci, E.L.; Milte, R.; Keogh, J.B. Developing and Piloting a Novel Ranking System to Assess Popular Ditery Patterns and Healthy Eating Principles. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashman, F.; Sturgiss, E.; Haesler, E. Exploring Self-Efficacy in Australian General Practitioners Managing Patient Obesity: A Qualitative Survey Study. Int. J. Family Med. 2016, 2016, 8212837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, K.; Grech, C.; Hill, K. Health advice and education given to overweight patients by primary care doctors and nurses: A scoping literature review. Prev. Med. Rep. 2019, 14, 100812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). A Series of Systematic Reviews on the Relationship between Dietary Patterns and Health Outcomes; US Department of Agriculture: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2014.

- Réda, A.; Wassil, M.; Mériem, M.; Alexia, P.; Abdelmalik, H.; Sabine, B.; Nassir, M. Food timing, circadian rhythm and chrononutrition: A systematic review of time-restricted eating’s effects on human health. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.; McInerner, P.; Muinn, Z.; Tricco, A.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munz, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, A.; Smith, D.; Booth, A. Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, D.; Hart, A. Family physicians’ perspectives on their weight loss nutrition counseling in a high obesity prevalence area. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2018, 31, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangler, J.; Jansky, M. Attitudes, behaviours and strategies towards obesity patients in primary care: A qualitative interview study with general practitioners in Germany. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2021, 27, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bąk-Sosnowska, M.; Skrzypulec-Plinta, V. Health behaviors, health definitions, sense of coherence, and general practitioners’ attitudes towards obesity and diagnosing obesity in patients. Arch. Med. Sci. 2017, 13, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornhoeft, K. Perceptions, Attitudes, and Behaviors of Primary Care Providers Toward Obesity Management: A Qualitative Study. J. Community Health Nurs. 2018, 35, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicker, D.; Kornboim, B.; Bachrach, R.; Shehadeh, N.; Potesman-Yona, S.; Segal-Lieberman, G. ACTION-IO as a platform to understand differences in perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors of people with obesity and physicians across countries-the Israeli experience. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2020, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudzune, K.A.; Wickham, E.P.; Schmidt, S.L.; Stanford, F.C. Physicians certified by the American Board of Obesity Medicine provide evidence-based care. Clin. Obes. 2021, 11, e12407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackey, C.; Plegue, M.A.; Deames, M.; Kittle, M.; Sonneville, K.R.; Chang, T. Family physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors regarding the weight effects of added sugar. SAGE Open Med. 2018, 6, 2050312118801245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, D.; McCarthy, E.; Carey, M.; Turner, L.; Harris, M. “90% of the time, it’s not just weight”: General practitioner and practice staff perspectives regarding the barriers and enablers to obesity guideline implementation. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 13, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeod, M.R.; Chionis, L.; Gregg, B.; Gianchandani, R.; Wolfson, J.A. Knowledge and attitudes of lower Michigan primary care physicians towards dietary interventions: A cross-sectional survey. Prev. Med. Reports 2022, 27, 101793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhoda, K.; Hosseinpour-Niazi, S.; Mirmiran, P. Nutritional knowledge, attitude, and practice of general physicians toward the management of metabolic syndrome in Tehran. Shiraz E Med. J. 2021, 22, e97514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.M.; Bélanger, A.; Carson, V.; Krah, J.; Langlois, M.; Lawlor, D.; Lepage, S.; Liu, A.; Macklin, D.A.; MacKay, N.; et al. Perceptions of barriers to effective obesity management in Canada: Results from the ACTION study. Clin. Obes. 2019, 9, e12329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanFrank, B.K.; Park, S.; Foltz, J.L.; McGuire, L.C.; Harris, D.M. Physician Characteristics Associated With Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Counseling Practices. Am. J. Health Promot. 2018, 32, 1365–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrkatić, A.; Grujičić, M.; Jovičić-Bata, J.; Novaković, B. Nutritional Knowledge, Confidence, Attitudes towards Nutritional Care and Nutrition Counselling Practice among General Practitioners. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, W.; Aveyard, P.; Albury, C.; Nicholson, B.; Tudor, K.; Hobbs, R.; Roberts, N.; Ziebland, S. A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies exploring GPs’ and nurses’ perspectives on discussing weight with patients with overweight and obesity in primary care. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, S.; Parretti, H.M.; Greenfield, S. Experiences and perceptions of dietitians for obesity management: A general practice qualitative study. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 34, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, J.; Lawrence, R.; Minx, J.C.; Oladapo, O.T.; Ravaud, P.; Tendal Jeppesen, B.; Thomas, J.; Turner, T.; Vandvik, P.O.; Grimshaw, J.M. Decision makers need constantly updated evidence synthesis. Nature 2021, 600, 383–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Component | Concept |

|---|---|

| S (sample) | General practitioners (GPs) |

| P of I (phenomenon of interest) | Dietary advice for weight loss |

| D (design) | Survey/Interview/Focus groups |

| E (evaluation) | Knowledge, attitude, and practice |

| R (research type) | Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods |

| Study Characteristics | n | Study Characteristics | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year of Publication | Methods | ||

| 2017 | 1 | Quantitative | 10 |

| 2018 | 4 | Qualitative | 3 |

| 2019 | 2 | ||

| 2020 | 2 | Disciplines Included | |

| 2021 | 3 | Mixed | 11 |

| 2022 | 1 | General/family practice only | 2 |

| Region | Area of Assessment Discussed | ||

| North America | 8 | Knowledge | 5 |

| South America | 0 | Attitudes | 6 |

| Europe | 2 | Practices | 11 |

| Asia | 2 | ||

| Africa | 0 | ||

| Australia | 1 |

| No. | First Author, Year | Aim/Objective | Location/Setting/Design | Participants | Dietary Advice Reported | Dietary Aspect Discussed | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bak-Sosnowska, 2017 [23] | To evaluate GPs’ attitudes towards health and to determine factors affecting diagnosis of obesity in their patients. | Poland Primary care in a refresher course Survey | 250 primary care (34% family doctors, 66% other specializations). Age: 25–65 years, mean age 53.6 years, average time since graduation 28 years, 84% women, 87% lived in city. | Mediterranean diet Low-glycemic index Reduce calorie intake Cambridge plan (very low calorie) | Quantity, Quality | Practice: 29.2% always giving advice about diet, 42.5% advised Mediterranean diet, 15.2% on glycaemic index, 4.4% Cambridge diet, 27.2% reducing calorie intake, 4% infusible diet, 6% hunger diet. |

| 2 | Bornhoeft, 2018 [24] | To explore perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors toward obesity management by providers in primary care. | U.S. Primary care practices Qualitative | 12 PCPs, 6 physicians, and 6 nurses. Inclusion: >1 year experience and see obese patients regularly. 70% women, 83% Caucasian, 67% had >10 years’ experience, aged 30–50 years. | Eat fruits and vegetables Shop at wholefoods | Quality | Practice: GPs said they tell people to eat fruit and vegetables and shop at Whole Foods and Trader Joes. |

| 3 | Dicker, 2020 [25] | To identify perceptions, attitudes, behaviors, and barriers to effective obesity treatment among people with obesity (PwO) and physicians in Israel. | Israel Health care practitioners (part of ACTION-IO) Survey | 169 healthcare practitioners (HCPs), including physicians, specialists, dieticians, pharmacists, nurses, diabetes educators. Inclusion: in practice for >2 years, at least 50% spent in direct care, had seen >100 patients in the past month, at least 10 patients with high BMI. | Reducing calories Specific diet (unexplained) Elimination diet | Quantity, Quality | Attitude: 84% agreed that reducing calories is effective, 38% agreed on specific diet, 46% agreed on elimination diets. Practice: 62% advised reducing calories, 35% specific diet, 47% elimination diet. |

| 4 | Gudzune, 2021 [26] | To determine the clinical services offered by the American Board of Obesity Medicine (ABOM) diplomates and whether guideline-concordant services varied by clinical practice attributes. | U.S. ABOM diplomates Survey | 494 ABOM diplomates physicians (response rate 19.2%). 37.5% practiced in urban areas, 11.3% in rural areas. | Adherence to guidelines: AHA/AACE/OMA/Endocrine Society | Guidelines | Practice: 30.8% of services offered aligned with AHA guideline, 33.4% with AACE, 65.6% with OMA, 31.6% with Endocrine Society, and 82.6% with any guideline used. |

| 5 | Hendrix, 2020 [12] | To examine the personal dietary weight-loss strategies of female physicians and what they recommended to their patients. | U.S. Physicians in Facebook-based group Survey | 1151 participants, members of “Women Physicians Weigh in” Facebook group. (Response rate 9%). Mean age: 40.2, 17.5% family medicine specialists, 81.9% white ethnicity, 56.5% 6–12 months in group. | Intermittent fasting Ketogenic diet Low-carbohydrate calorie restriction Prolonged fasting Mediterranean diet Paleo diet Vegan/vegetarian diet Whole30 diet Low-fat calorie restriction Very low caloriesDASH | Quantity, Quality, Timing | Practice: 21–35% advised intermittent fasting, 25–41% advised ketogenic diet, 30–47% low-carbohydrate calorie restriction, 1–2% prolonged fasting, 16–27% referred to commercial program, 17–22% advised Mediterranean diet, 5–11% paleo, 1–4% vegan, 6–13% Whole30, 3–4% low-fat calorie restriction, 1% very low calories, 8–58% DASH, 3–23% diabetes prevention program. |

| 6 | Mackey, 2018 [27] | To describe the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of family physicians regarding added dietary sugar. | U.S. Members of major family medicine organizations Survey | 1196 family physician members of the council of academic family medicine organizations. | Limit sugary beverages Avoid addition of sugar to foods | Quality | Knowledge: 15% were very familiar with research relating to added sugar, 30% were familiar with guidelines pertaining to added sugar consumption. Attitude: Majority believed excess added sugar contributed to excess body weight. Practice: 72% reported providing dietary counseling to the majority of patients. 97% advised against sugary beverage consumption and 82% advised limiting added sugar in food. |

| 7 | Mazza, 2019 [28] | To identify the views of GPs and general practice staff regarding barriers and enablers to implementation of obesity guideline recommendations in general practice. | Australia GP clinics Qualitative | 20 GPs and 18 practice staff (14 female). | Implementation of NHMRC guideline Cut down certain foods | Quality, Guidelines | Knowledge: Most had no knowledge on guidelines, six unsure if they had read the guidelines. Practice: One GP advised patients to reduce certain foods. |

| 8 | McLeod, 2022 [29] | To investigate primary care physicians’ current knowledge and opinions regarding the delivery of dietary interventions. This work aimed to identify modifiable barriers to prescribing dietary interventions to prevent and treat diet-related diseases. | U.S. Academic and community hospitals Survey | 356 physicians (response rate 23%). 62.3% female, 75.5% non-Hispanic white, 56.7% fewer than 10 years’ experience, 22.3% family medicine, 56.7% aged 40 or younger. | DASH diet Portion control Macronutrients content Keto/Saturated fat | Quantity, Quality | Knowledge: 40.3% had good/excellent knowledge of DASH, 59% on portion control, 24.7% on macronutrients, and 13.7% on saturated fat. |

| 9 | Nair, 2018 [21] | To examine physician weight-loss nutrition counseling among family physicians in Huntington, West Virginia, an area with the highest obesity prevalence in the United States. | U.S. Ambulatory practice Survey | 38 physicians (response rate 81%). 55% were between 35 and 55 years old, 53% men, listed in family medicine section in West Virginia, at least one practice site. | USDA My plate | Quantity, Quality | Practice: 18% using USDA MyPlate resources. |

| 10 | Nakhoda, 2021 [30] | To investigate the nutritional knowledge, attitudes, and practices of general physicians (GPs) toward the management of MetS. | Iran Health centers affiliated to university Survey | 500 physicians. Mean age: 42.8 years, 58% female. | Consume a variety of fruits and vegetablesVariety of whole-grains Fat-free and low-fat dairy Replace high-fat meat, red meat, and processed meat with fish, legumes, poultry, and lean meats Limit salt to less than 6 g/day Limit high-cholesterol foods (based on guidelines of METs) | Quality | Knowledge: 80% felt they had limited nutritional knowledge. Attitude: Agreement on: low sodium diet (21%), vegetables and fruits (21%), limiting starchy vegetables (72%), consuming high grain foods including refined grain (82%), limiting high-cholesterol food (100%) and high-fat dairy products (97%), replacing red meat with legumes (95%). Practice: Over half recommended reducing cholesterol intake, consuming low-fat dairy. 30% recommended consumption of a variety of grain products, fruits, vegetables; <25% recommended replacing high fats with fish/legume and reducing salt intake. |

| 11 | Sharma, 2019 [31] | To investigate perceptions, attitudes, and perceived barriers to obesity management among Canadian people with obesity (PwO), healthcare providers (HCPs), and employers. | Canada Physicians (part of ACTION-IO) Survey | 395 HCPs (including physicians, specialists, dieticians, pharmacists, nurses, diabetes educators) (response rate 34%). | General improvement in eating habits Elimination diets Specific diet program (unexplained) | Quantity, Quality | Attitude: 63% believed their role was to encourage general improvement in eating habits, 29% believed in elimination diets, 17% believed in a specific diet or diet program. |

| 12 | VanFrank, 2018 [32] | To explore SSB-related topics physicians discuss when counseling overweight/obese patients and examine associations between physicians’ SSB-related counseling and their personal and medical practice characteristics. | U.S. Physicians who participated in WorldOne’s medical panel Survey | 1510 physicians currently practicing in the U.S. Inclusion: actively seeing patients, at least 3 years of practice. 52.5% <45 years, 68.2% male, 60.9% non-Hispanic white, 35.9% family practice. | Frequency of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption Calorie content of SSBsAdded sugar in SSBs | Quality | Practice: 98.5% reported counseling patients on SSB, 63% advised about calorie content in SSBs, 53.1% advised about added sugars in SSBs, 63.8% advised about frequency of SSBs. |

| 13 | Wangler, 2021 [22] | To explore GPs’ attitudes and behaviors towards obese patients, willingness to provide care, approaches and strategies, and challenges experienced. | Germany GP clinic Qualitative | 36 GPs. | Healthy high-fiber diet | Quality | Practice: One GP mentioned that exercise combined with healthy high-fiber diet was reported to bring successful outcomes. (Results about attitudes in this paper were not related to specific approach, so were not included in the extraction) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rathomi, H.S.; Dale, T.; Mavaddat, N.; Thompson, S.C. General Practitioners’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Dietary Advice for Weight Control in Their Overweight Patients: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2920. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15132920

Rathomi HS, Dale T, Mavaddat N, Thompson SC. General Practitioners’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Dietary Advice for Weight Control in Their Overweight Patients: A Scoping Review. Nutrients. 2023; 15(13):2920. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15132920

Chicago/Turabian StyleRathomi, Hilmi S., Tanya Dale, Nahal Mavaddat, and Sandra C. Thompson. 2023. "General Practitioners’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Dietary Advice for Weight Control in Their Overweight Patients: A Scoping Review" Nutrients 15, no. 13: 2920. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15132920

APA StyleRathomi, H. S., Dale, T., Mavaddat, N., & Thompson, S. C. (2023). General Practitioners’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Dietary Advice for Weight Control in Their Overweight Patients: A Scoping Review. Nutrients, 15(13), 2920. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15132920