1. Introduction

Young adulthood is an important period to establishing good habits and healthy eating patterns to prevent the risk of chronic diseases that will affect people’s quality of life [

1]. University students seem to be influenced by some individual factors and their social networks [

2]. Socio-economic statuses influence diet quality; a good diet can reduce adolescent obesity and non-communicable diseases in the future. University is a stressful environment that is associated with unhealthy changes in eating behaviours in students due to university characteristics, such as living arrangements or academic schedules, which influence the relationships between individuals and their eating behaviours [

2,

3].

Protein requirements depend on age, fat free mass, physical activity and the severity of the disease. The recommended daily amount of protein that must be consumed is 0.8 g/kg/day in healthy individuals [

4,

5]. High-protein diets are characterised by a protein content that is above the recommended values [

6]. With respect to protein intake, no negative effects on kidney function have not been found after the consumption of 2.51–3.32 g/kg/d for one year, which is probably due to their high fibre intake of more than 30 g fibre per day [

7]. Related to that, Knight et al. observed that among females, high-protein intake was not associated with renal function decline in those with normal renal function; nevertheless, it may accelerate renal function decline in females with mild renal insufficiency with non-dairy intake [

8]. Jhee et al. on the contrary, noted that a high-protein diet has a deleterious effect on renal function in the general population [

9]. A high-protein intake is considered to increase the risk of renal hyperfiltration in individuals by inducing glomerular hypertrophy and an increased risk of hyperfiltration [

10]. Some food group characteristics of a proinflammatory diet, such as meat or processed foods, can produce health problems and increase the risk of some non-communicable diseases (obesity, hypercholesterolemia or diabetes) [

11].

COVID-19 provoked a myriad of challenges for people’s health, causing them to have a low level of life satisfaction and an unhealthy diet that could be associated with serious negative health outcomes and behaviours [

12,

13]. Depending on their socio-economic status, some individual’s habits are affected in different ways. The combination of stress, anxiety and depression due to this pandemic situation also had an impact on eating behaviours [

14].

The Perceived Stress Scale-14 (PSS-14) was designed to assess the degree of stress people felt in unpredictable and out-of-control situations. It has fourteen items, with seven negative and seven positive items [

15].

Emotional distress and anxiety appear to play a major role in the choice, quality and quantity of food intake, which could lead to an increase in BMI and lead to the consumption of unhealthy foods [

16,

17]. The association between diet and mental health is complex and bidirectional [

18]. As reported by Macht [

16], depending on the motivation to eat, emotional eaters regulate their emotions via the increased consumption of comfort foods. A study of adult females reported that those with high-level anxiety showed more unhealthy eating and food cravings [

17]. Lovan et al. observed that female students appeared to have lower susceptibility to their internal bodily signal signals of hunger and satiety and a higher reliance on emotions to initiate or end eating [

19]. More emotional changes occur in females during this period, and also, the researchers observed an association between alcohol consumption and the perception of apathy and anxiety related to food cravings between meals [

20]. Scott et al. noted that, in stressful situations and anxiety, people tend to regulate their emotions via eating [

21]. Gonçalves et al. observed in their study that only females reported having a food addiction [

22].

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) is an instrument used to assess subjective sleep quality and is also a reliable and valid instrument for university students [

23].

Due to globalisation, the importation of Western habits and shifts in lifestyle are probably among the potential drivers away from the traditional Mediterranean diet (MD). There are different indices used to measure Mediterranean Diet Adherence (ADM), and the indices are generally the food groups traditionally consumed by Mediterranean populations. However, other foods from non-Mediterranean areas and locally consumed ones may be inappropriately computed with these indices [

24]. Regarding alcohol consumption, for some young people, both food and alcohol are a source of pleasure of their social lives [

21].

The aim of this study was to compare the nutritional habits, alcohol consumption, anxiety and sleep quality among female health science university students.

3. Results

In

Table 2, we show the macronutrient intake data. When we compared the energy intake with the BMI of students, the median values did not show differences between underweight and overweight students (1610 kcal). Only slight, but not significant, differences were observed between the twenty-fifth and seventy-fifth percentiles. In this case, the underweight students had greater energy intake than the overweight students did. According to protein %E, the median was 17.8%, which is a higher value than that of the recommendations. Only 9.4% of students had a protein intake in line with the recommendations. With respect to fat %E, the median was 37.7%, which is a value higher than that which is recommended. With respect to this fat intake, 66.5% of female students had a fat %E higher than the recommended value. Regarding saturated fatty acids (SFA) %E and cholesterol, both values were also higher than those of the recommendations, as shown in

Table 2. On the other hand, the values of carbohydrates (CH) %E did not reach those that are recommended, being only 1%. Fibre intake was also scarce, with only 12% of students reaching the recommended fibre intake values. The effect size was high for carbohydrate %E and fibre intake, medium for protein, fat and SFA %E, and low for cholesterol.

When we compared the macronutrient intake data according to BMI (

Table 3), significant differences in fat %E (U = 1262,

p = 0.03) and cholesterol (U = 12301,

p = 0.01) were observed between the underweight and overweight/obese respondents.

In

Table 4, we show that the students mainly breakfasted every day, but 8.9% skipped breakfast. No differences were observed with respect to the reduction or not of food intake, and they mainly drank beer and spirits.

Table 5 shows that according to the results of PSQI, 82% of the female students had a poor sleep quality. With respect sleep efficiency, duration and subjective sleep quality, 16.5% had scores of less than 75%, and half of the students slept between 6–7 h/day, 26% slept ≤ hours/day, and finally, half of the students had quite good sleep quality, but among the 26%, it was bad or very bad. Finally, we highlight that 25% of female nursing students took sleep medication.

Table 6 shows that 13.5% presented with moderate–high food addiction, 56% had a medium level of adherence to the ADM, and 80.1% of participants need alcohol education.

In

Table 7, we show that participants who consumed fatty acids (FA) had higher levels of energy and fat intake due to the correlation between them, but less perceived stress, which was correlated inversely. Individuals with high levels of perceived stress consumed less energy and protein; on the other hand, a positive correlation between stress and anxiety states was observed. Finally, the anxiety trait was correlated with FA and fat (fat %E and SFA %E), and participants who consumed FA were less likely to adhere to the ADM.

In

Table 8, we show that FA was inversely correlated with ADM, which is in concordance with a significant BMI–fat %E relationship. An inverse correlation has also been observed between BMI and fibre; in this case, the higher the BMI is, the lower the level of fibre intake of the students is. Finally, participants with better ADM scores had higher-quality sleep, according to the correlation observed between the PSQI and ADM.

4. Discussion

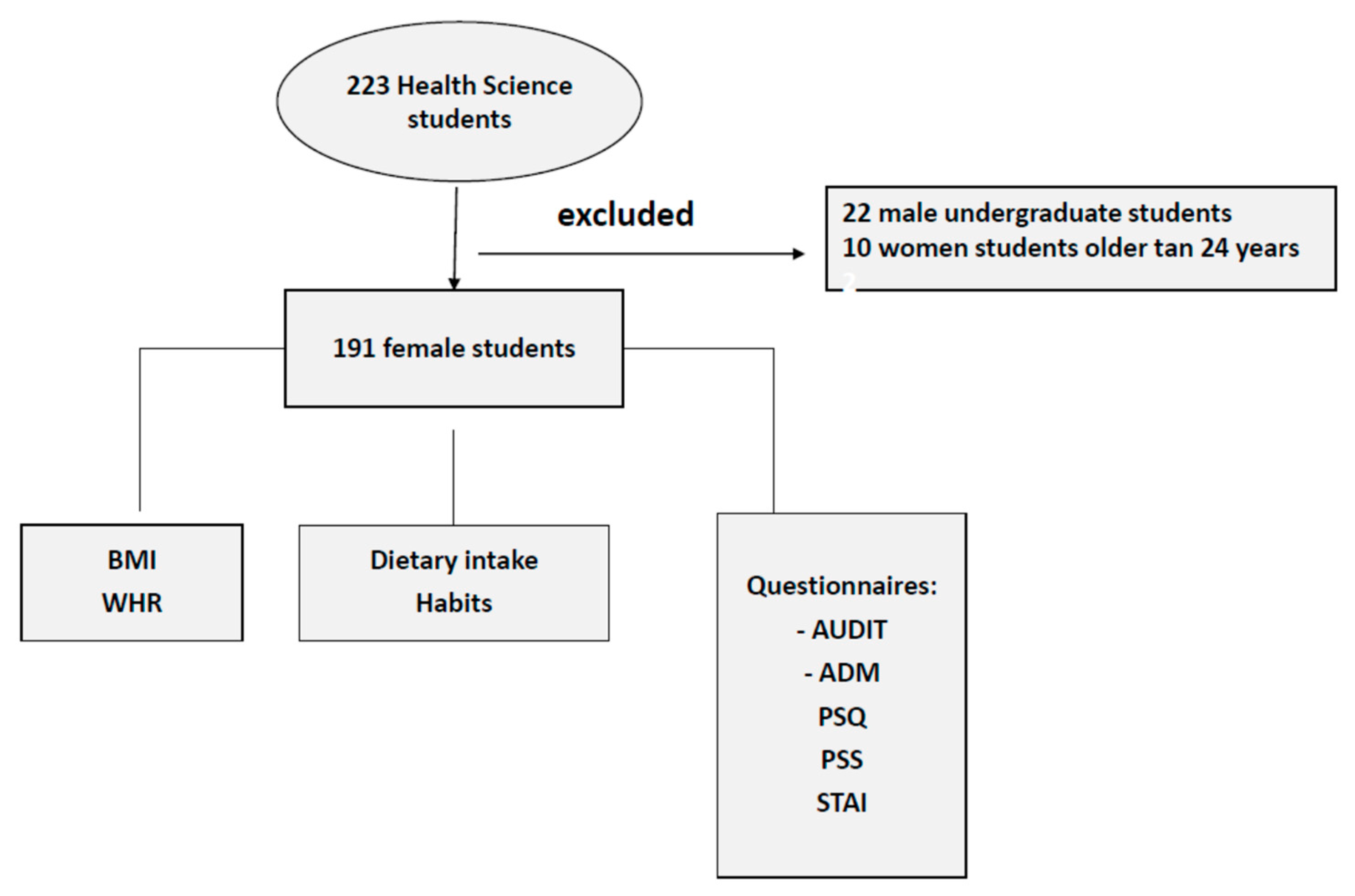

Changes in eating patterns are occurring worldwide. The purpose of this cross-sectional study was to identify the nutritional habits, alcohol consumption, anxiety and emotional eating and sleep quality of university health science students.

The present study highlights the elevated proportion of female students who do not meet the dietary guidelines, but differences in methodology and age classification occasionally make comparisons problematic. It is not the first time that poor eating habits among university students [

34] have been described. In this study, the macronutrients %E was markedly unbalanced as compared to the updated reference values of the EFSA and ANIBES studies [

35,

36]; protein %E (17.8%), fat %E (37.7%) and SFA %E (12.1%) were significantly higher than the recommended values, and it was lower for carbohydrates %E (37.7%). The percentages calculated serve to classify this dietary pattern within the so-called low-carbohydrate–high-protein diet spectrum (LCHP diet) [

37].

These results were consistent with previous studies carried out among other university students [

38,

39]. With respect to protein %E, only 9.4% were within the recommended range, which was also observed in the ANIBES study [

40]. However, if we compared our results with those recommended by the Institute of Medicine (10–35%), the values were under the lower limit. The Institute of Medicine, in fact, reported very a high level of protein intake (>35% E) without negative effects [

6]. On the other hand, it is accepted that excessive long-term protein consumption may counteract an adequate energy profile [

40]. Protein-rich diets have been demonstrated to be effective at lowering a person’s body weight, without negatively affecting cardiovascular health markers, such as the cholesterol and triglyceride levels in plasma. However, there are some concerns about their potential long-term negative effects, as studies carried out using animal models show kidney, hepatic and cardiovascular alterations [

41,

42], while, in humans, the evidence remains inconclusive [

43].

Our data show a significant inverse correlation between BMI and protein %E, as is expected due to the metabolic effects of a protein-rich diet. It has been shown that high-protein diets promote body weight reduction over the long-term, which is in part due to an increase in the sleeping metabolic rate (SMR) [

44,

45], and also, a significant increase in dietary energy expenditure (DEE) [

46,

47] in comparison with those of normal composition diets. Additionally, a long-term high-protein diet (%E P > 20%) in healthy individuals promotes more satiety in comparison with that of diets with a standard protein composition (%E P < 15%) [

37] due to the release of GLP-1 and insulin [

48].

In this study, female students’ macronutrient imbalances were noted with high-protein intake diets, which were inversely correlated with BMI. In a study with a Chinese population, high-protein meals led to reductions in the total energy intake and were associated with a lower body weight, BMI, waist circumference, higher adiposity and correlated with saturated fatty acids [

49]. When comparing macronutrient intake with BMI, the results were similar to Chinese–American university students [

39]. No differences were detected between the underweight and overweight students, but we observed a greater energy intake in the underweight students than we did in the overweight students.

We also found a negative trend in fat intake, with a fat %E of 37.7%, which is a value that is above the recommendations [

50]. With respect to fat intake, 66.5% of female students had a fat %E that was higher than the recommended value. This is in concordance with the fat intake level in Spain, which is at the upper end of the recommended value, and certain types of dietary fat may contribute to cardiovascular diseases [

40]. Regarding SFA %E and cholesterol, both values were at the upper end of the recommendations. Even so, the EFSA, FAO and the Spanish Federation of Food, Nutrition and Dietetic Societies (FESNAD) have recommended a maximum intake of 10% E for SFA in the adult population [

51,

52].

The Spanish population, however, is well below the lower limit of CH, which is considered to be a poor indicator of their present diet quality [

40]. In this study, CH %E did not reach the value recommended by the EFSA of 45–60%E, whereas the SENC recommended 50–60%E. However, as observed in the ANIBES study, the Spanish population was below the lower limit, and that is an indicator of poor diet quality [

40,

53,

54]. Our values for CH %E did not reach the recommendations, and similar results were observed among Spanish females. Their fibre intake level was also poor, with only 12% of students reaching the recommended fibre intake values. When we compared the above intakes according to BMI, significant differences were observed between the students with a normal weight and those with overweight/obesity. According to their BMI, the relationship between underweight and overweight/obese students was significant only for fat %E intake (

p = 0.007).

Eating breakfast may be an important dietary behaviour for cardiometabolic health. Therefore, consuming breakfast is common among young adults and is the most frequently skipped meal [

55]. Ferrara et al., during COVID pandemic period, observed that, in 2021, 42.9% more females ate breakfast than they did in the beginning and pre-pandemic periods [

56]. In this study, this daily unhealthy habit was 8.9%, a higher value than that which was observed in a Basque university, which was 5% [

57]. There is strong evidence of an association between breakfast skipping and overweight/obesity [

48], but in this study, there was a lack of association between overweight/obesity and skipping breakfast. In a cross-sectional study, students who skipped breakfast were more vulnerable to alcohol consumption and its toxic effects [

58]. Furthermore, in this study, a lack of a significant association was observed between both unhealthy habits.

Regarding drinking behaviour, 80.3% were alcohol drinkers, who mainly drank beer (30.9%) and spirits (20.9%), which is similar to the results observed by Scott et al. among young adults in the UK [

21]. In this study, underweight and overweight/obese students drank more alcohol than the others did, and significant differences (

p < 0.05) were observed between the underweight and normal weight students according to type of beverage (beer and spirits) consumed. More than 2/3 of respondents in this study need alcohol education, and depending on their social context, they responded that they drank mainly beer and spirits with friends. As reported by Scott et al. [

21], on their days off, young adults visiting take away food shops consume large amounts of alcohol and often also eat unhealthy food.

Low-quality sleep seems to be particularly common among university students [

59,

60], with reported prevalence rates of 50–70% for low-quality sleep being assessed with the PSQI [

32]. Descriptive statistics in this study showed that up to 82% of the sample reported low-quality sleep according to the PSQI, and 26% had a habitual sleep duration < 7 h, which is the minimum amount of sleep conventionally recommended for young adults and adults [

61]. Finally, we highlight that 25% of female nursing students took sleep medication. In this study, participants with better ADM scores had significantly high-sleep quality.

Another finding of this study was that 56% of female students presented mid-range AMD scores, similar as previously observed in Spanish nursing students; the health benefits of a Mediterranean diet across the Mediterranean basin have been demonstrated, and it is important to promote the AMD among future health professionals [

34,

62,

63].

It has been observed that stress and emotional conditions modulate eating behaviour [

34]. This is in concordance with the significant relationship detected between BMI and fat %E and lower intake of fibre when the BMI increased. Dakanalis et al. also found an association between BMI and eating behaviours [

64], and some negative dietary habits could be due to the stressful situation during the pandemic situation [

20]. ElBarazi and Tikamdas found a positive association between fatty food intake, stress, anxiety and BMI, which is contrary to the healthy and adequate nutrient intake that benefits mental health [

65]. Among Portuguese university students, no differences were obsrved between food addiction and BMI during the pandemic situation, which could have promoted healthier or unhealthier eating habits [

22].

The perceived stress score among female students was 23, which indicated a medium level of stress, where the stress ranged from 0 to 56 [

33]. In this study, perceived stress was inversely correlated with the intake of energy and protein %E intake. Similarly, Pal et al. suggested that stress negatively affects emotional regulation and may promote unhealthy eating behaviour and hedonic eating [

66].

Some limitations should be considered. One of them is the preponderance of female participants, which makes generalisation for both sexes difficult. We avoided male university students due to the small size of the accessible population. The study comprises nursing students, and during the period of study, the students were experiencing stressful situations because it was conduced the examination period.