Abstract

This systematic review aims to identify and characterize existing national sugar reduction initiatives and strategies in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. For this purpose, a systematic review of published and grey literature was performed. A comprehensive list of search terms in the title/abstract/keyword fields was used to cover the four following concepts (1) sugar, (2) reduction OR intake, (3) policy and (4) EMR countries. A total of 162 peer-reviewed documents were identified, until the 2nd of August 2022. The key characteristics of the identified national strategies/initiatives included the average sugar intake of each country’s population; sugar levels in food products/beverages; implementation strategies (taxation; elimination of subsidies; marketing regulation; reformulation; consumer education; labeling; interventions in public institution settings), as well as monitoring and evaluation of program impact. Twenty-one countries (95%) implemented at least one type of sugar reduction initiatives, the most common of which was consumer education (71%). The implemented fiscal policies included sugar subsidies’ elimination (fourteen countries; 67%) and taxation (thirteen countries 62%). Thirteen countries (62%) have implemented interventions in public institution settings, compared to twelve and ten countries that implemented food product reformulation and marketing regulation initiatives, respectively. Food labeling was the least implemented sugar reduction initiative (nine countries). Monitoring activities were conducted by four countries only and impact evaluations were identified in only Iran and Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). Further action is needed to ensure that countries of the region strengthen their regulatory capacities and compliance monitoring of sugar reduction policy actions.

1. Introduction

Countries of the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR) are witnessing the nutrition transition, with its characteristic shifts in food consumption patterns and lifestyle [1]. One of the main features of the nutrition transition is an increase in the consumption of sugar, sweetened processed foods and beverages [2,3]. This may pose a public health threat given that high sugar intakes were proposed to increase the risk of excessive weight gain and cardiometabolic diseases in the population [4,5].

Sugars may occur naturally in foods, including fruits, vegetables, and milk/dairy products, but may also be added to food items during preparation and processing [5,6]. There are different terminologies that have been proposed to discriminate between the different types of sugar. The term “Total Sugars” (TS) refers to all mono- and disaccharides that are present in a food item or beverage, whether added or naturally occurring. In contrast, the term “Added Sugars” (AS) refers only to sugars that were intentionally added to foods/beverages in order to improve palatability, impart a sweet flavor, preserve and/or confer specific functional attributes [5]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has proposed the term “Free Sugars” (FS), which comprises “monosaccharides and disaccharides added to foods and beverages by the manufacturer, cook, or consumer (i.e., AS), plus sugars naturally present in honey, syrups, fruit juices, and fruit juice concentrates (i.e., non-milk extrinsic sugars)” [7]. The FS term is thus utilized when referring to sugars that may have physiological effects that are different from those attributed to intrinsic sugars found within intact plant cell walls or naturally occurring lactose in milk [5,8].

High consumption of sugar, particularly AS and FS, has been linked to poor overall dietary quality, and excessive energy intake (EI), while contributing to energy imbalance [9,10,11,12]. Excessive sugar intakes in adults have been implicated in the epidemics of obesity, cardiovascular disorders, type 2 diabetes, non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases, and their downstream cardiometabolic abnormalities such as metabolic syndrome, dyslipidemia and chronic inflammation [13,14,15]. It was also reported that both high sugar intakes and hyperglycemia can affect the intestinal barrier, thus heightening gut permeability and leading to profound gut microbiota dysbiosis and disturbances in mucosal immunity, which in turn can increase susceptibility to infections [13]. In addition, a recent meta-analysis has reported a significant association between high sugar intake and increased risk of cognitive disorders in middle-aged and elderly populations [16]. In the pediatric and adolescent population, high intake of sugar was associated with an increased risk of overweight and obesity [17,18], dyslipidemia [19], insulin resistance [20], as well as dental caries [21].

Health agencies in the United States (US) have recommended up to 10% of total calories from AS [22]. In 2015, the WHO updated dietary guidelines pertinent to sugar intake and recommended decreasing the intake of FS to less than 10% EI as a ‘strong recommendation’ [7], and to less than 5% as a conditional recommendation [7]. The Scientific Advisory Council on Nutrition in England adopted a relatively similar approach, providing a recommendation of 10% of calories from AS, with the ultimate goal of achieving an even lower intake of 5% [23]. The American Heart Association has called for even stricter restrictions on calories from AS, with a proposed upper limit of no more than 150 kcal per day for the average adult man and no more than 100 kcal of AS per day for the average adult woman [24,25]. In 2022, the European food safety agency (EFSA), recommended that the intake of “added and free sugars should be as low as possible in the context of a nutritionally adequate diet”.

In countries of the EMR, food supply data show that the contribution of sugar (as a commodity) to capita daily food energy supply has been following a consistently increasing trend over time, with estimates of its average contribution to energy supply ranging between 9% and 15% [1,26]. At the same time, the region harbors one of the highest burdens of obesity worldwide, coupled with an alarming increase in the incidence and prevalence of diet-related noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) including cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), type 2 diabetes and certain types of cancer [1]. In 2016, the WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean Region has set a policy goal to lower sugar intake “in order to reduce the risk of NCDs in children and adults, with a particular focus on the prevention of unhealthy weight gain and associated conditions, such as diabetes and dental caries”. The WHO EMR policy document included a set of measures for the reduction of sugar intake, including the reformulation of sugar-rich foods and drinks; setting standards for all foods and beverages served by government-sponsored institutions; restricting the promotion of sugar-enriched products, especially beverages; imposing restrictions on the marketing of sugar-enriched foods and drinks across all media platforms; adopting nutritional profiling system to set clear definitions for high sugar foods and drinks; eliminating national sugar subsidies and introducing progressive taxes initially on sweetened beverages and ultimately on all foods and drinks with AS; improving and facilitating accredited training on diet and health for individuals with opportunities to affect population food choices; and providing public education on nutrition and health. The reduction of sugar has also been included as a priority action in the WHO strategy on nutrition for the Eastern Mediterranean Region, 2020–2030 [27], and the regional framework for action on obesity prevention 2019–2023 [28]. Despite the guidance provided by the WHO EMR on sugar reduction policies, there has been no systematic appraisal of national sugar reduction efforts in various countries of the EMR. It is in this context that this systematic review was performed with the aim of identifying and documenting existing national sugar reduction strategies and initiatives in countries of the EMR, and assessing the impact of these strategies when available data allows it.

2. Materials and Methods

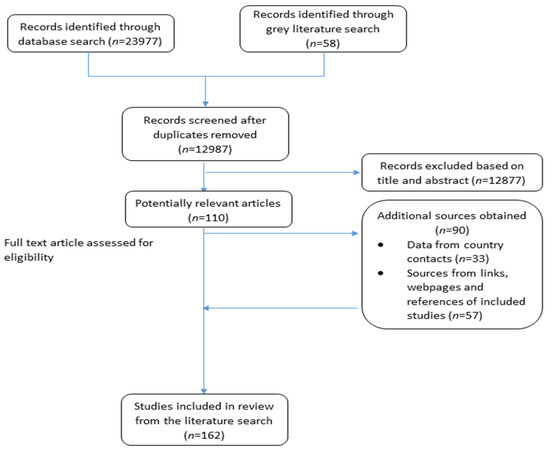

This study was written in conformity with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Table S1) and was not registered in PROSPERO. The search strategy and methodology adopted in this study are comparable to the approach adopted in previous studies [29,30,31]. In brief, data related to sugar reduction strategies and initiatives were identified based on a search of peer-reviewed as well as grey literature, in addition to obtaining supplementary information by establishing direct contact with program country leaders or focal points (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Search and identification process of potential references from the literature.

2.1. Search Strategy

A search of 11 electronic databases was conducted between 24 March 2021 and 5 April 2021. These databases comprised: Directory of Open Access Journals, CAB Direct, MEDLINE (ovid), PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science Core Collections, Food Science and Technology Abstracts, Al Manhal, Arab World Research Source (AWRS), E-Marefa and Iraqi Academic Scientific Journals (IASJ). The last 4 databases are specific to the Arab region, whereby Arabic keywords were used in the search. In addition to the use of a controlled vocabulary (MeSH in PubMed and MEDLINE (ovid)), a comprehensive list of search terms was also used in the title/abstract/keyword fields to cover the four following concepts (1) sugar, (2) reduction OR intake, (3) policy and (4) EMR countries. Table A1 in Appendix A provides the detailed list of the search terms used pertaining to the four concepts while searching the various databases. In addition, an example of a database search is provided in Table S2 for MEDLINE (ovid). In the search, materials that were published in the English, Arabic or French languages were considered, and any material published prior to 1995 was excluded. Articles that were published after the initial search were identified via email alerts (up until 29 August 2022).

A search of the grey literature was also conducted, using OpenGrey, Google Scholar, the Global Database on the Implementation of Nutrition Action (GINA), the WHO EMRO (Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean) website as well as governmental websites (such as the websites of the Ministries of Health in the various EMR countries). This search focused on materials published post 1995 in English, Arabic or French languages. Two independent researchers (MT and LN) performed the screening of the titles, abstracts and full text articles of relevant articles, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria described in the section below. The two researchers engaged in discussions to resolve the minor discrepancies that emanated from the two screening stages.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Articles were included in this systematic review if they provided information on sugar baseline assessment (including intake of sugar; levels in foods/beverages; knowledge, attitudes and behavior (KAB), or the development, implementation, monitoring/evaluation of sugar reduction initiatives at the national level).

National sugar reduction initiatives/strategies were defined as having a governmental body involved [26,32,33], in addition to one or more of the following: (1) a national action plan to reduce sugar intake at the population level [26,32]; (2) a sugar reduction/replacement program (e.g., setting limits for the levels of sugar in food products) [26,33]; (3) awareness campaigns or consumers’ education programs aimed at improving sugar-related KAB [26]; (4) labeling schemes that are specific to sugar/AS or mandatory declaration of sugar/AS on nutrition labels [26,33]; (5) taxation policies targeting high sugar foods and beverages [26,32,33]; (6) eliminating sugar subsidies [26,32]; (7) regulation of the marketing of high sugar foods/beverages [26,33]; and (8) sugar reduction initiatives in specific settings (such as schools, hospitals, workplaces, etc.) [26,33].

Studies that are based on randomized-control trial design or case-control studies, as well as those dealing with unhealthy individuals or specific population groups (such as pregnant women, individuals on therapeutic diets etc.) were excluded from the review. Individual studies/articles were also excluded from the review if they were published prior to 1995, or in any language other than English, Arabic or French.

2.3. Data Extraction

Data extraction was performed by two researchers (MT and LN). For the few discrepancies between the researchers, consensus was reached via discussion.

The key characteristics of each sugar reduction initiative were entered into a database that was developed by the researchers to examine baseline assessments (population TS intake; population AS intake; population FS intake; sugar levels in food products/beverages, sugar-related KAB), leadership and strategic approach, implementation strategies (taxation; elimination of subsidies; regulation on the marketing of high-sugar foods and beverages; product reformulation; consumer education; food labeling; interventions in public institution settings), monitoring (population intake, levels in food products/beverages, KAB), and evaluation of program impact [26,32,33].

2.4. Seeking Supplementary Information

A questionnaire was developed based on relevant literature [34,35] and was shared with country experts or program leaders in various countries of the EMR to confirm and obtain supplementary data, if available. Country experts or program leaders were invited to complete the questionnaire and/or share it with their local contacts to seek additional information and details. Accordingly, the database was updated with any additional data.

2.5. Analysis

The key characteristics of each of the identified national sugar reduction strategy were entered into the database, according to the pre-developed framework that includes baseline assessments; leadership/strategic approach; implementation strategies; data monitoring and evaluation of program impact. Countries were then classified as ‘having a developed strategy’ for sugar reduction, ‘having a planned strategy’ or ‘having no strategy’. Strategies were considered to be “planned” if the sugar reduction initiatives were still under development, or if an action plan had already been established but without evidence of implementation. The proportion of countries reporting on each of the key characteristic were determined, and expressed as percentages.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

In total, 162 peer-reviewed articles, grey literature documents, websites and references from country contacts were identified via the literature search. Of these, 72 were peer-reviewed relevant articles, and 90 were additional documents/sources obtained from country contacts (through the questionnaires), webpages, links, and references from within the included articles (Figure 1).

3.2. Assessment of Sugar Intake

Out of the 22 countries of the EMR, thirteen (59%) had estimates pertinent to TS intake, while only four (18%) had estimates of AS or FS intake. Sugar intake assessments were not identified in the following countries: Djibouti, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Somalia, Syria and Yemen (Tables S3–S5).

Total Sugar intakes: Some of the studies had estimated TS intakes at the national level for certain age groups (such as adults, children or adolescents), or for the entire population (i.e., per capita), while others had produced estimates pertinent to specific regions within countries [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62]. Table S3 presents data pertinent to TS intakes in countries of the region, whether these intakes were reported as g/day or % EI. Except for Iran, Jordan and Pakistan where TS intake assessment was based on a household budget survey, all the other countries had assessed TS intakes based on dietary assessment approaches such as 24-h recalls, diet records, food diaries, or food frequency questionnaires (Table S3)

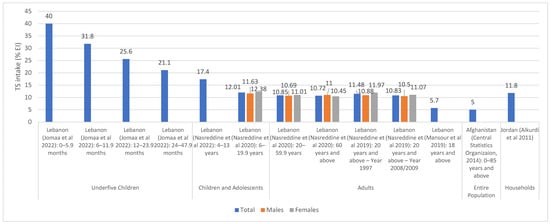

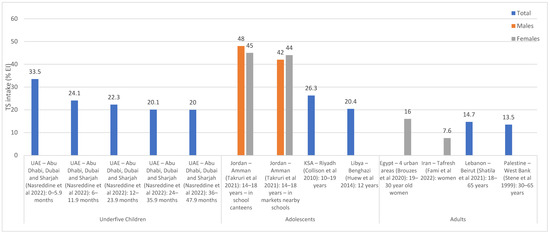

Figure 2 and Figure 3 illustrate TS intakes as % EI, based on national and regional studies (i.e., specific regions within a country), respectively. As shown in Figure 2, national surveys conducted in Lebanon (and which were based on dietary assessment approaches) showed that TS intake ranged between 17.4% EI and 40% EI among underfive children, the highest being in 0–6 month old children [57]. In Lebanese children and adolescents, the intake of TS was estimated at 12% EI [39], while in adults, it ranged between 10.5 and 12% EI [39,41]. The study in Afghanistan reported a per capita estimate of 5% EI based on a 7-day food consumption recall [44], while the household budget survey conducted in Jordan reported an estimate of 11.8% EI [46] (Figure 2). As for regional studies (Figure 3), TS intake levels among adults were estimated at 13.5% EI and 14.7% EI in Palestine (West Bank) and Lebanon (Beirut) [55,61], respectively, and rural women in Iran (7.6%) [54], while being slightly higher among urban women in Egypt (16% EI) [53] (Figure 3). Among the few countries that have evaluated TS intake among adolescents, Jordan (Amman) reported the highest levels (42–48% EI) [60], while Libya (Benghazi) reported the lowest (20.4% EI) [52]. TS intakes were also estimated among underfive children in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) (the Emirates of Abu Dhabi, Dubai and Sharjah), ranging between 20% and 33.5%, the highest estimate being observed in 0–6 months old infants [59].

Figure 2.

TS intake estimates (% EI) based on national studies in countries of the EMR. Abbreviations: EI: energy intake; EMR: Eastern Mediterranean Region; TS: total sugars. References: For underfive children: Lebanon (dietary assessment): Jomaa et al., 2022 [57]. For children and adolescents: Lebanon (dietary assessment): Nasreddine et al., 2022 [37]; Lebanon (dietary assessment): Nasreddine et al., 2020 [39]. For adults: Lebanon (dietary assessment): Nasreddine et al., 2020 [39]; Lebanon (dietary assessment): Nasreddine et al., 2019 [41]; Lebanon (dietary assessment): Mansour et al., 2019 [42]. For entire population: Afghanistan (consumption data): Central Statistics Organization 2014 [44]. For households: Jordan (Households Income and Expenditure Survey): Alkurdi et al., 2011 [46].

Figure 3.

TS intake estimates (% EI) based on regional studies in countries of the EMR. Abbreviations: EI: energy intake; EMR: Eastern Mediterranean Region; KSA: Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; TS: total sugars; UAE: United Arab Emirates. References: For underfive children: UAE (dietary assessment): Nasreddine et al., 2022 [59]. For adolescents: Jordan (dietary assessment): Takruri et al., 2021 [60]; KSA (dietary assessment): Collison et al., 2010 [51]; Libya (dietary assessment): Huew et al., 2014 [52]. For adults: Egypt (dietary assessment): Brouzes et al., 2020 [53]; Iran (dietary assessment): Fami et al., 2002 [54]; Lebanon (dietary assessment): Shatila et al., 2021 [61]; Palestine (dietary assessment): Stene et al., 1999 [55].

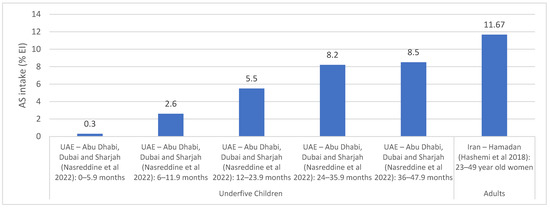

Added sugar and free sugar intakes: AS intakes were assessed based on dietary assessment approaches including 24-h recalls, food diaries, and food frequency questionnaires (Table S4). National studies were only identified in Lebanon with AS intake being estimated at 11.2% EI among 4–13 year old children and adolescents [37]. Other countries have provided estimates based on studies conducted within specific regions [37,38,53,59,63,64], as shown in Figure 4. The UAE (Abu Dhabi, Dubai and Sharjah) reported an average intake ranging between 0.3 and 8.5% among under 4 years old, with the intake increasing with age [59]. In Iran (Hamadan), an intake of 11.7% EI was noted among adult women [64].

Figure 4.

AS intake estimates (% EI) based on regional studies in countries of the EMR. Abbreviations: AS: added sugars; EI: energy intake; EMR: Eastern Mediterranean Region; UAE: United Arab Emirates. References: For underfive children: UAE (dietary assessment): Nasreddine et al., 2022 [59]. For adults: Iran (dietary assessment): Hashemi et al., 2018 [64].

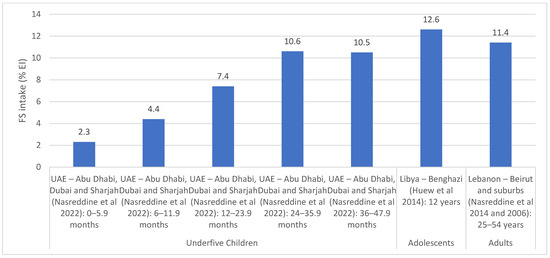

Similar to AS, Lebanon was the only country with national estimates for FS intakes, while Libya, Tunisia and the UAE had estimates from specific regions [38,40,52,59,65,66,67,68]. National surveys conducted in 2012 and 2014 in Lebanon showed that the intake of FS ranged between 6.3 and 11.9% EI among underfive children and between 12.6 and 12.9% EI among children and adolescents aged 6–18 years [40] (Table S5). The main contributors of FS were sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) (14.9–29.3% of FS intake), biscuits and chocolates (11–12.7%), breads and pies (10.7–12.4%) and sweetened dairy products (9.8%) among under five children, while the main contributors among older children and adolescents were SSBs (13.8–43.5%), biscuits, wafers and chocolates (10.6–14.7%), and syrups, jams and honey (9–9.3%) [38,40]. The regional studies that were conducted in countries of the region are shown in Figure 5. Among adults, FS intake was estimated at 11.4% EI in Beirut, Lebanon [66,67], while in Libya (Benghazi), an intake of 12.6% EI was reported among 12 year old adolescents [52]. A study by Aounallah-Skhiri et al. conducted in 3 regions of Tunisia reported that among adolescents aged 15–19 years (n = 1019), FS intake (26.8 g/1000 kcal) exceeded the recommended level (10% EI) [65,69]. The study also showed that sugar and confectionary were among the main constituents of the diet among Tunisian adolescents [65]. Among underfive children, average FS intakes were estimated to range between 2.3 and 10.6% EI among underfive children in the UAE (Abu Dhabi, Dubai and Sharjah) [59], with the intakes increasing with age.

Figure 5.

FS intake estimates (% EI) based on regional studies in countries of the EMR. Abbreviations: EI: energy intake; EMR: Eastern Mediterranean Region; FS: free sugars; UAE: United Arab Emirates. References: For underfive children: UAE (dietary assessment): Nasreddine et al., 2022 [59]. For adolescents: Libya (dietary assessment): Huew et al., 2014 [52]. For adults: Lebanon (dietary assessment): Nasreddine et al., 2014 and Nasreddine et al., 2006 [66,67].

3.3. Compliance/Adherence to Sugar Recommendations

Among the few national studies in the EMR, studies conducted among children and adolescents in Lebanon showed that 24.8–54.2% of underfive children and 58.1–62.2% of 6–18 year olds exceeded the WHO FS upper limit (10% EI) [7,38,40]. In the UAE, a regional study on children under the age of 4 years (Abu Dhabi, Dubai and Sharjah) showed that 28% of children aged 12–23.9 months exceeded the upper limit for FS, while 54% and 52% of those aged 24–35.9 months and 36–47.9 months, respectively, exceeded the upper limit for FS [59,70]. A study conducted in KSA (n = 424) showed that only 0.9% of children aged 6–12 years consumed FS within the WHO conditional recommendation of <5% EI, whereas 10.6% consumed FS within the recommendation of <10% EI [7,71]. Based on the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study (n = 2510 adults aged 19–70 years), the majority of adults in Tehran, Iran (82.2% of males and 89.8% of females) were found to be adherent to the WHO/Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) recommendations for FS (i.e., <10% of EI) [69,72].

For AS, national studies conducted in Lebanon showed that only 29.1% of Lebanese children and adolescents were compliant with the AS recommendations set by the American Heart Association (no more than 25 g per day) [37,73] (Table S4). In Sudan, and based on the WHO STEPS survey among adults aged 18 to 69 years, the average weekly intake of AS was estimated at 6.3 teaspoons, which was reported to be within the WHO recommended daily intake of 50 g i.e., 12 level teaspoons [43,74].

3.4. Assessment of Sugar Levels in Food and Sugar-Related KAB

Few countries in the EMR (6/22 countries; 27%), including Iran, Jordan, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar and Tunisia, have evaluated sugar levels in local foods and commodities (Table S6) [75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82]. While the majority of available sugar content data were based on the chemical analysis of food products [75,77,78,79,82], few were derived from software analysis (such as ESHA and NutriComp) [76] or nutrition information labels [80]. High levels of sugar were reported in bakery products, ready-to-eat cereals, chocolate and biscuits [80,82]. The lowest levels of sugar (<10 g per 100 g of food) were found in traditional dishes, mayonnaise and salad dressings [75,76,77,78]. Moreover, Iran was the only country that showed decreasing sugar levels in food products (such as salad dressings) between 2017 and 2019 [75].

As for data on KAB, this information was available in 10 EMR countries (45%), including Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Jordan, KSA, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman and Pakistan. The majority of KAB surveys included questions related to (1) knowledge of sugar food sources, sugar content in food products, and familiarity with adverse weight/health effects of high sugar intakes; (2) consumer’s attitude such as importance of restricting/limiting the intake of sugar, making healthier choices and checking information related to sugar; and (3) consumers’ behavior such as consuming high sugar food products, reducing the amount of AS, substituting high-sugar options with healthier options and reading labels (Table S7) [72,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116]. Poor knowledge related to sugar food sources and content was reported from more than 65% of school-aged children in Jazan, KSA [98]. In addition, 77.5% of male schoolchildren in Riyadh, KSA [100], 61% of college students in Muscat, Oman [107] and 85% of adults in Rawalpindi cantonment in Pakistan [111], were unaware of the adverse health effects of high sugar consumption. A national study in Lebanon showed that less than 50% of adolescents and adults did not know what a “sugar-free” claim indicates [116]. As for attitude, more than 80% of schoolchildren in Jazan, KSA preferred high sugar foods and beverages, as compared to healthier options [98]. Among the studies that assessed consumer behavior, a regional study in KSA showed that less than 50% of mothers try to limit the purchase of foods that are high in FS [91], and several studies reported the consumption of high sugar foods and beverages among various age groups. For example, 87.5% of children aged 3–5 years in Zaghouan, Morocco had diets high in sugar [106]; more than 80% of children in Beirut, Lebanon added sugar to their beverages [104]; more than 90% of schoolchildren in Jazan, KSA frequently consumed soft drinks, sweets, milk with sugar and chocolate [98]; 79–83.4% of university students in Karachi, Pakistan consumed cakes, biscuits and soft drinks on a daily basis [113]; and more than 80% of households reported a daily consumption of sugar in Iran [87,88]. In a regional study in KSA, it was reported that only 1.7% of mothers were successful in limiting/controlling their child’s FS intake [91]. Moreover, while 32.6% of female university students in KSA were making an effort to reduce AS intakes [93], only 10.9% of elderly in Nizwa, Oman were restricting sugar in their diet [108].

3.5. Countries with National Sugar Reduction Initiatives

Table 1 and Table 2 show the national sugar reduction initiatives that were identified in all of the countries of the EMR, except for Syria (21 countries; 95%).

Table 1.

Sugar reduction implementation strategies in countries of the EMR: Taxation, subsidies and marketing regulations.

Table 2.

Sugar reduction implementation strategies in countries of the EMR: product reformulation, consumer education, labeling and interventions in specific settings.

3.6. Leadership and Strategic Approach

National strategies or action plans that express a commitment to reduce sugar in the population were identified in 4 EMR countries; Jordan, KSA, Morocco and Oman (Table 3). All of the identified strategies were led by the government and were part of broader strategies or action plans targeting NCD or healthy diets and lifestyle. Jordan and KSA have specified, in their strategies, the reduction of FS and monosaccharides, respectively [220,221,222].

Table 3.

National sugar reduction strategies or action plans identified in the EMR countries.

3.7. Implementation Strategies

3.7.1. Taxation, Elimination of Subsidies and Regulation of Marketing

The majority of the EMR countries (19/21 countries; 90%), with the exception of Libya, Somalia and Syria are implementing or planning strategies related to taxation, elimination of sugar subsidies or the regulation of marketing of high-sugar products, with varying degrees in implementation and policy scope (Table 1). Marketing regulation was the least common implementation strategy (10/21 countries; 48%), followed by taxation (13/21 countries; 62%) and then subsidies’ elimination (14/21 countries; 67%).

Taxation is mandatory in 4 countries of the region (Bahrain, KSA, Oman, and Qatar) (Table 1). The first taxation initiatives that were initiated in 2017 in KSA, Qatar, Tunisia and the UAE, have targeted SSBs. KSA and UAE have also extended taxation to include energy drinks and other sweetened food products [118,120,121,132,133,134,135,136,156,158,159,160,161,162]. In addition, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan and Qatar are planning to extend the SSB tax to other sugar rich food products [145,146,147,148,149].

While Iran is implementing a taxation of 10% on local soft drinks and 15% on imported ones (planned to reach 20% on SSBs) [120], Kuwait is implementing a tax of 50% on carbonated beverages and 100% on energy drinks [137]. Oman is already implementing a taxation of 100% on energy drinks and 50% on soft drinks since 2020 [150,151]. Morocco implemented a progressive taxation on sugary drinks in proportion to the quantity of AS (threshold of 5 g/100 mL) [144]. In Afghanistan, there has been a proposal to tax sugary drinks since 2015, but this has not been adopted or implemented yet [117,118]. Similarly, in 2017, Egypt has developed a taxation strategy targeting SSBs; however there is no evidence of its implementation yet [125] (Table 1).

Marketing regulation is mandatory in Jordan and Palestine only (the latter being a planned strategy). While the majority of countries implementing marketing strategies focused on sugar in general (Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine, Qatar and UAE) [121,130,131,139,143,155,156,159], other countries have targeted FS (Bahrain) [119], AS (Iran) [127,128], monosaccharides (Iraq) [129] or specifically energy drinks (Pakistan) (Table 1).

Of the 14 countries that have considered subsidies elimination, Oman was the only country that has planned, but not yet adopted, a gradual shift in subsidization from sugars and unhealthy fats to healthy foods instead (to reach 100% by 2025) [152]. Bahrain, is planning to eliminate sugar subsidies [122], while Qatar and the UAE have planned the elimination of any subsidies for sugar-rich food items [156,161,162]. Djibouti, Egypt, Iran, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Pakistan, Sudan, Tunisia and Yemen are eliminating food subsidies for sugar used in industries [123,124,126,138,153,164] (Table 1).

3.7.2. Food Product Reformulation, Consumer Education, Labelling and Interventions in Specific Settings

The majority of the EMR countries (18/21 countries; 86%), with the exception of Djibouti, Egypt, Syria and Yemen are implementing or planning strategies related to food product reformulation, consumer education, labeling or interventions in specific settings. The most common intervention was consumer education (15/21 countries; 71%), followed by interventions in specific settings (13/21 countries; 62%), product reformulation (12/21 countries; 57%) and food labeling initiatives (9/21 countries; 43%). Table 2 displays the details of the initiatives implemented/planned in the various countries.

Twelve countries (57%), including Bahrain, Iran, Jordan, KSA, Kuwait, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, Palestine, Qatar, Tunisia and the UAE, are implementing/planning product reformulation initiatives in the region. Iran and Kuwait were the first countries in the EMR to have developed food product reformulation strategies on drinks, nectars, biscuits and cakes, in 2016 [168,187]. Morocco will be mandating the reduction of AS by 25% in all foods and beverages by 2025 [198,199]. As for Palestine, mandatory technical instructions have been planned since 2017 to reduce sugar in food products [155]. Similarly, Pakistan has planned a mandatory product reformulation intervention targeting all foods and snacks in 2022 (Table 2). In 2016, Oman has developed an initiative aimed at encouraging food manufacturers to produce smaller-sized portions of products that are high in sugars, but it has not been adopted yet [152].

Fifteen countries (71%) have implemented/planned consumer education campaigns. These countries include Afghanistan, Iran, Jordan, KSA, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, Palestine, Qatar, Somalia and the UAE; while Sudan has an initiative that has not yet been adopted (Table 2). Although the majority of awareness and educational campaigns were led by governmental entities in countries of the region, the American University of Beirut and the National Center for Disease Control were the main leaders in Lebanon and Libya, respectively. The WHO, FAO and Aljisr Foundation were collaborators in Oman, and similarly the WHO, FAO, a non-governmental organization (NGO), Pakistan National Heart Association and Diabetic Association of Pakistan were collaborators in Pakistan alongside the government. Libya and Palestine had consumer education initiatives related to AS, while Somalia had initiatives that were specific to FS (Table 2).

Nine countries (43%), including Iran, KSA, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, Tunisia and the UAE, were found to have implemented/planned food labeling initiatives specific to sugar. Mandatory initiatives were found in Iran, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan and the UAE (7/9 countries; 78%), with the traffic light labeling scheme being implemented in Iran (mandatory) [121,170,171,172,173,174], KSA (voluntary) [182,186] and the UAE (to become mandatory in 2022) [173,217], while it awaits approval in Kuwait (Table 2).

Thirteen countries (62%) are implementing/planning sugar reduction interventions in specific settings. These countries include Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, KSA, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, Palestine, Qatar and the UAE. While all countries have interventions in schools and/or educational institutions, Jordan, KSA, Qatar and the UAE have implemented interventions in other settings. For instance, in Jordan, the Ministry of Health in collaboration with the army sector, has developed an intervention to reduce sugar in menus served to workers and patients in hospitals [177]. As part of the Food & Beverage Guidelines, and the educational sessions in schools and workplaces in Qatar, voluntary guidelines are being implemented in hospitals and the workplace. In the UAE, interventions targeting prisons, juvenile centers, police and military schools, army forces, geriatric home cares and their canteen, as well as health care facilities were developed [161,219]. In KSA, several initiatives have been implemented in various governmental settings (hospitals, universities, military, public and private work environment) and included replacing high-sugar items with healthier options and placing sugar-related claims on sugar packets [182,185] (Table 2).

3.8. Monitoring and Evaluation

There are few countries that have conducted monitoring and evaluation activities. In Iran, food items available in primary schools’ canteens in Tehran were evaluated [176], and compliance with the guidelines was assessed by comparing nutrient content of food items (TS, AS and non-sugar sweeteners) with the WHO EMR nutrient profile model [226] and Iran Healthy School Canteen Guideline [175]. The findings showed that 9.2% of chocolates, sugar confectionery and desserts that were available in the school canteens, as well as 15.7% of beverages and 45.2% of cakes, sweet biscuits and pastries, are not permitted based on the WHO EMR model [176,226]. Similarly, 13.7% of chocolates, sugar confectionery and desserts found in the canteens, 19.7% of beverages and 28.8% of cakes, sweet biscuits and pastries are not permitted based on the national guideline [175,176]. Also in Iran, 239 food stores around 64 primary schools in Tehran, were visited in 2018–2019 [227], and the nutrition information on the labels of packaged foods available in these stores were examined. It was found that 89.6% of chocolates, sugar confectionery and desserts, 27.8% of ice cream, 50% of popsicles, 60% of breakfast cereals and 45.9% of cakes, sweet biscuits and wafer had high levels of sugar (classified as greater than 22.5 g per 100 g or greater than 11.25 g per 100 mL or greater than 27 g per serving) [227].

In Jordan, food labels of 663 packaged products in the market were screened for AS, based on the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations of 2016 and the Jordanian FDA (JFDA) regulations. Although the examined products were compliant with the JFDA regulations, they were not fully compliant with the US FDA standards [228]. A study on 76 public high schools, specifically for boys, in Riyadh, showed that the majority (93–99%) of schools were still offering cakes, muffins, confectionaries, biscuits and cookies [229]. As for Kuwait, and following the implementation of the product reformulation initiative in 2016 to reduce AS content in nectars, fruit juices and SSBs [187], a monitoring and evaluation assessment was conducted in 2017–2018. The findings have shown that the reduction of sugar in nectars ranged between 5–28%, while that of drinks ranged between 2–10% [187].

3.9. Impact Assessment

The impact of some taxations schemes was examined. Impact assessment of the sweetened beverage tax was performed in Iran, using data from Iran’s Households Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) (from 1990 to 2021) [230]. The results showed that the taxation scheme produced a 144.23, 450.04 and 977.94 Kcal monthly decrease in EI per Adult Male Equivalent in all households, low-income households and high-income households, respectively [230].

In KSA, the impact of SSBs taxation was assessed. A cross-sectional study on schoolchildren aged 12–14 years, in Dammam-Khobar-Dhahran cities, showed that there was a decrease in energy drinks consumption (46.1% before tax implementation vs. 38.4% after tax implementation), while the consumption of soft drinks increased (92.5% before tax implementation vs. 94.6% after tax implementation) [136]. However, among adults aged 18–45 years in Medina city, soft drink consumption was shown to decrease by 19% after tax implementation [231]. In terms of annual purchases, the 2004–2018 Euromonitor annual data showed that the annual purchases (volume per capita) of soda and energy drinks were reduced by 41% and 58%, respectively in 2018 (post tax implementation) as compared to 2016 (prior to tax implementations) [232]. Another study measured the impact of sin taxes over the years in KSA, and showed similar findings whereby sales volumes of soft drinks decreased by 57.64% from 2010 to 2017, the year during which sin taxes were implemented [233].

4. Discussion

This systematic review reports on sugar reduction initiatives in countries of the EMR, a region that harbors a high burden of obesity, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular morbidity [1]. It showed that, out of the 22 countries in the EMR, 13 had estimates of TS intakes, while only 4 reported on the intakes of AS or FS. In addition, 21 countries (95%) were found to implement at least one type of sugar reduction initiatives, the most common of which was consumer education (71% out of the countries that have initiatives), while the least common was food labeling initiatives (43% out of the countries that have initiatives).

Although the majority of countries have reported on TS intakes, these intake estimates cannot be compared to health-related reference values given that TS encompasses all sources of sugar, including the intrinsic sugar of whole fruits as well as sugar present in milk and dairy products [5]. This explains the high level of TS observed among infants and young children in Lebanon and the UAE, whereby TS intakes were the highest in infants (31.8–40% EI in Lebanese infants under 1 year [57]; 24.1–33.5% EI in the UAE in the same age group [59]), reflecting their high consumption of milk in this stage of the lifecycle. Although scarce, available data in the region show that AS and FS intakes remain high, exceeding the upper limit of 10% EI in various age groups. For instance, average AS intake was estimated at 11.7% EI among adult women in Iran (Hamadan) [64], while average FS intake was estimated at 11.4% EI among Lebanese adults [66,67]. Data among children and adolescents is particularly alarming. In school-age children, it was reported that 58.1–62.2% of 6–18 year old Lebanese children exceed the WHO FS upper limit (10% EI) [7,38,40], and in KSA, only 10.6% of children aged 6–12 years consumed FS within the recommendation of <10% EI [7,71]. Studies conducted among underfive children also highlight high intakes of sugar in this age group. For instance, 24.8–54.2% of underfive children in Lebanon [7,38,40] and 28–54% in the UAE [59,70] were found to exceed the upper limit of FS (10% EI).

The present review shows that multicomponent sugar reduction approaches have been implemented in several countries of the region. This is a positive finding since an integrated policy approach may further foster the impact and effectiveness of sugar reduction strategies [35,234,235]. The WHO EMR policy statement for lowering sugar intake [26], has in fact included recommendations for multifaceted interventions for the reduction of sugar intake, including financial policies, food reformulation, food labelling, consumer education, marketing regulations and interventions in specific settings. The most common sugar reduction approach in the EMR was consumer education, which was adopted by 15 countries in the region (71%), with the aim of raising awareness about sugar, its main dietary sources and its potential adverse health effects. For example, the reduction of sugar intake has been included in country-specific food-based dietary guidelines in Afghanistan, Iran, Jordan, KSA, Lebanon, Libya, Oman, Pakistan, Palestine, Qatar and the UAE. Such guidelines and their dissemination to the public has been reported as a practical and effective approach in ameliorating dietary knowledge and attitudes among consumers [236,237]. Some studies in the region had in fact assessed consumers’ knowledge and attitudes towards sugar. These studies have shown that consumers have poor or little knowledge related to the sources of sugar or their content in foods [98], as well as the potential health effects of high sugar intake [100,107,111]. A negative attitude towards sugar reduction or the consumption of healthier low-sugar foods had been also reported from countries of the region [98]. In addition, from the few available studies on practices, a study in KSA showed that less than half of mothers try to limit the purchase of foods that are high in FS [91], and that only 1.7% of mothers were successful in limiting their child’s FS intake [91]. Similarly, it has been reported that high proportions of school-aged children or university students add sugar to their beverages [104] and consume SSBs and sweets on a daily basis [98,113]. It is recommended that countries of the region refer to findings stemming from the available studies on population, knowledge, attitude and practice to further tailor their consumer education initiatives and address culture-specific knowledge gaps and barriers against sugar reduction.

Fiscal policies have been implemented in various countries of the region, including sugar subsidies’ elimination (14 countries; 67%) and taxation (13 countries each; 62%). These estimates highlight a significant progress, compared to earlier reports from the region. In 2016, the first Global Nutrition Policy Review reported that only 24% of countries in the EMR were implementing fiscal policies [238], while our findings show that this proportion has increased to 77% of the 22 countries of the region. The EMR as a region has had a sugar subsidizing policy as part of a strategy to support the poorer sections of the community [26]. However, the importance of eliminating sugar subsidies has recently gained momentum in the region, basically driven by the WHO EMR. For instance, the EMR policy statement on sugar reduction clearly states that countries ought to “review national food subsidies and progressively reduce and finally remove them as a policy mechanism for improving the health of the poor and access to health services” [26]. In Oman, and as part of the National plan for the prevention and control of chronic NCDs 2016–2025, there is a plan to gradually shift subsidization from sugars and unhealthy fats to healthy foods instead, to reach 100% by 2025 [152].

The implementation of taxation policies in the region was found to vary between countries with respect to the tax rate (as percentage of price), the included beverages, and whether taxation was extended to sugar-rich foods. Taxation policies in countries of the region have mainly focused on SSBs (13 countries). However other countries have included other beverages such as energy drinks (7 countries) and juices (3 countries), with some countries also implementing/planning to extend the taxation to sugar-containing foods (2 countries are implementing and 4 are planning). While the majority of countries have implemented a taxation of 50% on SSBs (such as Bahrain, KSA, Kuwait, Morocco, Oman, Qatar and the UAE), Iran is planning to reach 20%. In addition, several countries (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar and the UAE) have implemented a taxation rate of 100% on energy drinks, while KSA has adopted a taxation rate of 120%. Available evidence from various parts of the world suggests that SSB taxation leads to a reduction in the sales of taxed beverages, although studies examining the influence of SSB taxation on consumption have produced mixed results [34,35]. Taxation effects on sales and intake may in fact depend on several country-specific factors such as taxation rate, baseline SSB intake, type of beverage taxed, as well as population demographics [34].

Thirteen countries (62%) in the region have implemented sugar-reduction interventions in specific settings (mandatory or voluntary). Together with other initiatives and policies, these interventions could send a clear and coherent message to the public and industry, and address exposure to high sugar foods and beverages in the many places where people learn, work, and play [34]. While the most common setting for these interventions were schools in the EMR, some countries have implemented sugar-reduction initiatives in the workplace and in hospitals. The nature of these interventions varied between countries but mainly aimed at limiting the availability of SSBs/foods in these settings. Such interventions can in fact decrease the target population’s exposure to sweetened beverages/foods while making healthier beverages more accessible [34]. Research investigating the impacts of availability restriction on consumption is limited, but available evidence is promising [34]. A study investigating the impact of a workplace SSB ban at a California hospital showed that employees who were previously regular SSB consumers had reduced their daily intake by approximately half and had witnessed significant reductions in their waist circumference measurements [239].

Product reformulation has been implemented by 12 countries in the region (57%), mainly through setting targets/standards for sugar, either through mandatory regulation or co-regulation with the food-industry. Food reformulation is in fact one of the interventions recommended by the WHO to improve the nutritional quality of the food supply and hence the population’s diet [240]. Available studies suggest that policies targeting the reformulation of foods are cost-effective [35,241], and that these policies may have greater health impacts than those focusing on changing consumer behavior [242,243]. At the international level, there are few examples of policies setting targets/standards for AS or FS in packaged foods. Since 2008 in France, 37 food manufacturers and retailers have signed the government’s Charters of Voluntary Engagement to reduce sugar in their products [35]. It was then estimated that close to 13,000 tonnes of sugar were removed from the French food market between 2008 and 2010 [244]. In the UK, the health impact of three policy scenarios on health (obesity, diabetes, dental carries) were assessed, including product reformulation, increasing product price, or changing the market share of high-sugar, mid-sugar, and low-sugar drinks [245]. Out of the three modelled scenarios, the best was found to be reformulation [245].

The regulation on the marketing of high-sugar foods and beverages was found to be implemented/planned in 10 countries of the region (48%). The marketing of high sugar foods and beverages is becoming increasingly aggressive in the EMR as the Region represents a suitable marketing opportunity due to the limited regulatory restrictions [26]. Carefully constructed counter-marketing campaigns, which have led to efficient reductions in SSB sales in the US and Australia [246,247], were described as effective tools that could complement any sugar reduction policy. The EMR policy statement on sugar reduction highlighted the need for special measures to address the unopposed marketing of high sugar foods and beverages and to regulate marketing of unhealthy food and drinks to children through the use of the WHO regional nutrient profile model [26,226].

Food labeling initiatives (9 countries; 43%) were found to be the least implemented sugar reduction initiative in the region. Front of pack labeling, mainly the traffic light, has been implemented mandatorily in Iran, and on a voluntary basis in KSA, Kuwait and the UAE (with a plan to become mandatory in the latter as of 2022). Front-of pack labels provide simple and easy-to-understand information that help the consumer in making healthier food choices [34], while also incentivizing the food industry to reformulate their products [34]. Front-of-pack labels are expected to have a larger impact on consumer’s purchasing behavior and food choice, as compared to the numeric information found in the Nutrition Facts Panel on the side or back of food packages. The latter approach (numeric nutrient facts panel) was found to be implemented by 5 countries in the region, thus highlighting the need for more efforts on the promotion and implementation of front of pack labeling in the EMR. It is also important for labelling schemes implemented in the region to focus on AS instead of TS per se. A recent meta-analysis found that food labelling initiatives (including back of pack and menu labelling) that focus on TS only were not associated with any significantly reduction in sugar content in foods [248].

This systematic review showed that some countries have included a legislative component within their sugar reduction strategies, instead of solely implementing voluntary initiatives. It was previously shown that mandatory or legislative approaches tend to be more effective, leading to more significant reductions in sugar intakes within the population, compared to voluntary strategies [35]. A recent review has indicated that, although all policy approaches may result in reductions in the levels of sugar in foods and subsequent intakes, stronger policies (i.e., mandatory ones) will carry more pronounced impacts than voluntary food reformulation or labeling initiatives [35].

The implementation of clear monitoring activities is crucial to show program effectiveness, and to spur greater impact on sugar reduction [249,250]. In the EMR, few countries have conducted monitoring activities related to their sugar reduction initiatives. These included Iran, Jordan, KSA and Kuwait, although none had clearly established mechanisms for the monitoring of sugar reduction initiatives/programs. The few countries that have conducted monitoring activities have reported poor compliance. For instance, the majority of schools (93–99%) in Kuwait are still offering cakes, muffins, confectionaries, biscuits and cookies [229], and a considerable proportion of foods and beverages (9.2–45.2%) available in schools in Iran were described as “not permitted” based on the Iran Healthy School Canteen guidelines [175,176,226].

Data on the impact of sugar reduction initiatives is limited in the region. Except for Iran and KSA, there were no studies or reports examining the impact of sugar reduction policies in the other countries of the EMR. In Iran, the impact of the sweetened beverage tax was assessed, and the results showed that the taxation scheme produced a 144.23 Kcal monthly decrease in EI per Adult Male Equivalent [230]. In KSA, the impact of SSBs taxation was assessed. In terms of annual purchases: the Euromonitor annual data showed that the annual purchases of soda and energy drinks were reduced by 41% and 58%, respectively, post tax [232]. Although there was a decrease in the consumption of energy drinks among school-aged children [136], and soft drinks among adults [231], the intake of soft drinks seems to have increased among school-aged children (92.5% before tax implementation vs. 94.6% after tax implementation) [136]. The scarcity of impact data in the region, may be partially due to the fact that many sugar reduction initiatives are relatively recent and there has been insufficient time to allow for the assessment of impact. There is a crucial need for well-constructed impact evaluations in countries of the region. In addition, since the regular evaluation of changes in population sugar intake and sugar levels in foods may be costly and complex, the inclusion of process evaluations that assesses policy implementation and its progress, collects data on process indicators, and identifies existing facilitators and barriers to the implementation is also crucial in providing real-time information, and highlighting specific areas for improvement [251].

This review has a number of strengths and limitations. It is the first systematic review of existing sugar reduction initiatives and policies in countries of the EMR. The review relied on a systematic search of databases and grey literature, but also sought additional input from focal points or program leaders in the various countries of the EMR, to confirm and obtain supplementary country-specific data. Although we could not identify all country contacts and there were some non-respondents, the triangulation of information from various sources allowed us to identify and characterize the existing initiatives and implementation strategies, and present the information in a relatively standardized approach. Through this multifaceted methodology, it is unlikely that any major sugar reduction initiatives were missed, although this possibility cannot be totally discounted. While one of the important strengths of the review is the fact that it included an inclusive search of the grey literature, encompassing governmental reports and questionnaires completed by country program leaders, a possible limitation of this approach is the fact that the methodological rigor within some of these reports/questionnaires was not ascertained. More specifically, the robustness of the studies’ designs, their methodology and the quality of the data used for the evaluation of sugar intake and sugar levels in foods were not examined and hence data should be interpreted with caution. It is also important to note that studies that have reported on the intakes of AS and FS were very scarce and that dietary estimation of AS/FS sugar intake levels is inherently limited by the scarcity of up-to date, culture-specific food composition databases, and by the poor consumer knowledge of the potential food sources of AS/FS.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review showed that, despite the scarcity of data, the intakes of AS and FS remain high in countries of the region, exceeding the upper limits set by the WHO in all age groups, especially among children and adolescents. Except for Syria, all countries were found to implement at least one type of sugar reduction initiatives, the most common being consumer education, followed by fiscal policies (sugar subsidies’ elimination and taxation), interventions in public institution settings, product reformulation, marketing regulations and finally food labeling initiatives. A positive finding of this review is that several countries were found to implement multicomponent interventions for sugar reduction, which, as described in the literature, are expected to exert a larger impact compared to single policy initiatives [34]. However, data on the monitoring and impact assessment of the implemented sugar-reduction initiatives was very limited in the region. Further action is needed to make sure that countries strengthen their regulatory capacities and compliance monitoring of sugar reduction policy actions, and meet the targets sets in their national action plans and strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu15010055/s1, Table S1: PRISMA Checklist, Table S2: Example of a Database Search, Table S3: Estimates of TS Intakes in Countries of the EMR; Table S4: Estimates of AS Intakes in Countries of the EMR, Table S5: Estimates of FS Intakes in Countries of the EMR, Table S6: Sugar Levels in Food and Meals, Table S7: Knowledge, Attitudes and Behavior (KAB) towards Sugar in countries of the EMR. Reference [252] is cited in the supplementary materials

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.-J. and L.N.; methodology, L.N.; investigation, A.A.-J. and L.N.; resources, A.A.-J. and L.N.; systematic database search, S.N.; data curation, M.T. and L.N.; writing—original draft preparation, L.N.; writing—review and editing, M.T. and A.A.-J.; supervision, A.A.-J. and L.N.; project administration, A.A.-J. Critical review of country-specific data and of manuscript: H.A., N.A.H., S.A., H.A.A.-T., S.A.A., R.B., M.H. (Maha Hoteit), M.H. (Munawar Hussain) and H.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of WHO or the other institutions with which the authors are affiliated.

Abbreviations

AS: added sugars; AWRS: Arab World Research Source; CNPS: Community Nutrition Promotion Sector; CVD: cardiovascular diseases; EFSA: European food safety agency; EI: energy intake; EMR: Eastern Mediterranean Region; EMRO: Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean; FAO: Food and Agriculture Organization; FBDG: food-based dietary guidelines; FNA: Food and Nutrition Authority; FDA: Food and Drug Administration; FOP: front of pack; FOPL: front of pack labelling; FS: free sugars; GCC: Gulf Cooperation Council; GINA: Global Database on the Implementation of Nutrition Action; GSO: GCC Standardization Organization; GZAT: General Authority of Zakat, Tax and Customs; HIES: Households Income and Expenditure Survey; IASJ: Iraqi Academic Scientific Journals; IOM: Institute of Medicine; JFDA: Jordanian Food and Drug Administration; KAB: knowledge, attitudes and behavior; KP: Khyber Pakhtunkhwa; KSA: Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; MOCI: Ministry of Commerce and Industry; MOF: Ministry of Finance; MOH: Ministry of Health; MOHAP: Ministry of Health and Prevention; MOPH: Ministry of Public Health; NA: not available; NCD: non-communicable disease; NFP: nutrition focal point; NGO: non-governmental organization; PAFN: Public Authority for Food and Nutrition; SFDA: Saudi Food and Drug Authority; SSBs: sugar-sweetened beverages; TOT: training of trainers; TS: total sugars; TV: television; UAE: United Arab Emirates; UK: United Kingdom; UN: United Nations; US: United States; WHO: World Health Organization.

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of search terms.

Table A1.

List of search terms.

| Sugar | sugar* OR sucrose OR syrup* OR beverage* OR cola OR drink* OR soda OR sweet* OR chocolate* OR “ice cream*” OR candy OR candies OR cookie* OR jam OR confectioner* OR confectionar* OR cake* OR jelly OR jellies OR pastries OR pastry OR biscuit* OR bakery OR bakeries OR juice* OR honey OR pie OR pies OR dessert* OR cacao OR jam OR “chewing gum*” OR liquorice* OR marmalade* OR SSB OR cereal* OR smoothies OR milkshake* OR molasses OR fructose OR glucose |

| AND | |

| Reduction OR Intake | (reduce* OR reduction* OR reducing OR decreas* OR limit OR limits OR limitation* OR limiting OR restrict* OR reformulat* OR low*) OR (consumption OR consuming OR consume OR consumes OR intake* OR food* OR nutrition OR diet* OR source*) |

| AND | |

| Strategy/policy | standard* OR polic* OR initiative* OR tax* OR program* OR regulation* OR strateg* OR guideline* OR practice* OR legislat* OR action* OR plan OR plans OR intervention* OR law* OR campaign* OR marketing OR advertise* OR label* OR incentive* OR ban* OR recommendation* OR subsidy OR subsidies OR fiscal OR levy OR levies OR levied OR price* OR pricing OR excise* OR fee OR fees OR fine OR fines OR cost* |

| AND | |

| EMR | Afghan* OR Bahrain* OR Iran* OR Persia* OR Iraq* OR Jordan* OR Kuwait* OR Lebanon* OR Lebanese OR Libya* OR Oman* OR Palestin* OR Gaza* OR “West Bank” OR Qatar* OR Saud* OR KSA OR Syria* OR Tunis* OR “United Arab Emirate*” OR UAE OR Djibouti* OR Egypt* OR Morocc* OR Pakistan* OR Somal* OR Sudan* OR Yemen* OR Levant* OR “East* Mediterranean” OR Gulf OR GCC OR Arab OR Arabia OR Arabs OR EMR OR “Middle East*” OR MENA OR “North* Africa*” OR “East* Africa*” OR “Near East*” OR “Abu Dhabi” OR Dubai OR Ajman OR Fujaira* OR Sharja* OR *Khaima* OR *Qaiwain OR *Quwain |

Abbreviations: EMR: Eastern Mediterranean Region; KSA: Kingdome of Saudi Arabia; UAE: United Arab Emirates. *: Refers to a technique (known as truncation) used in research when searching databases, in order to broaden the search and ensure the inclusion of the various word endings and spelling.

References

- Sibai, A.M.; Nasreddine, L.; Mokdad, A.H.; Adra, N.; Tabet, M.; Hwalla, N. Nutrition transition and cardiovascular disease risk factors in Middle East and North Africa countries: Reviewing the evidence. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2010, 57, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M.; Adair, L.S.; Ng, S.W. Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr. Rev. 2012, 70, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popkin, B.M. Nutrition transition and the global diabetes epidemic. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2015, 15, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinho, A.R.; Severo, M.; Correia, D.; Lobato, L.; Vilela, S.; Oliveira, A.; Ramos, E.; Torres, D.; Lopes, C.; Consortium, I.-A. Total, added and free sugar intakes, dietary sources and determinants of consumption in Portugal: The National Food, Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey (IAN-AF 2015–2016). Public Health Nutr. 2019, 23, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fidler Mis, N.; Braegger, C.; Bronsky, J.; Campoy, C.; Domellöf, M.; Embleton, N.D.; Hojsak, I.; Hulst, J.; Indrio, F.; Lapillonne, A. Sugar in infants, children and adolescents: A position paper of the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Committee on Nutrition. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 65, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess, J.; Latulippe, M.E.; Ayoob, K.; Slavin, J. The confusing world of dietary sugars: Definitions, intakes, food sources and international dietary recommendations. Food Funct. 2012, 3, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Sugars Intake for Adults and Children; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/149782/9789241549028_eng.pdf;jsessionid=77485E8F53EB13D8F39A95ECC0E89A9B?sequence=1 (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Mesana, M.; Hilbig, A.; Androutsos, O.; Cuenca-Garcia, M.; Dallongeville, J.; Huybrechts, I.; De Henauw, S.; Widhalm, K.; Kafatos, A.; Nova, E. Dietary sources of sugars in adolescents’ diet: The HELENA study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, E.; Rodriguez, P.; Valero, T.; Ávila, J.M.; Aranceta-Bartrina, J.; Gil, Á.; González-Gross, M.; Ortega, R.M.; Serra-Majem, L.; Varela-Moreiras, G. Dietary intake of individual (free and intrinsic) sugars and food sources in the Spanish population: Findings from the ANIBES study. Nutrients 2017, 9, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexy, U.; Sichert-Hellert, W.; Kersting, M. Associations between intake of added sugars and intakes of nutrients and food groups in the diets of German children and adolescents. Br. J. Nutr. 2003, 90, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Marshall, T.A.; Eichenberger Gilmore, J.M.; Broffitt, B.; Stumbo, P.J.; Levy, S.M. Diet quality in young children is influenced by beverage consumption. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2005, 24, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiNicolantonio, J.J.; Berger, A. Added sugars drive nutrient and energy deficit in obesity: A new paradigm. Open Heart 2016, 3, e000469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnone, D.; Chabot, C.; Heba, A.-C.; Kökten, T.; Caron, B.; Hansmannel, F.; Dreumont, N.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Quilliot, D.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Sugars and gastrointestinal health. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 20, 1912–1924.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, R.; Schmidt, L.; Brindis, C. Public health: The toxic truth about sugar. Nature 2011, 482, 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, V.S.; Hu, F.B. Sugar-sweetened beverages and health: Where does the evidence stand? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 1161–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Shi, M.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xia, Y. Meta-analysis of sugar-sweetened beverage intake and the risk of cognitive disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 313, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libuda, L.; Kersting, M. Soft drinks and body weight development in childhood: Is there a relationship? Curr. Opin Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2009, 12, 596–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosini, G.L.; Johns, D.J.; Northstone, K.; Emmett, P.M.; Jebb, S.A. Free sugars and total fat are important characteristics of a dietary pattern associated with adiposity across childhood and adolescence. J. Nutr. 2015, 146, 778–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, J.A.; Sharma, A.; Cunningham, S.A.; Vos, M.B. Consumption of added sugars and indicators of cardiovascular disease risk among US adolescents. Circulation 2011, 123, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondaki, K.; Grammatikaki, E.; Jiménez-Pavón, D.; De Henauw, S.; Gonzalez-Gross, M.; Sjöstrom, M.; Gottrand, F.; Molnar, D.; Moreno, L.A.; Kafatos, A. Daily sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and insulin resistance in European adolescents: The HELENA (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence) Study. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheiham, A.; James, W. Diet and dental caries: The pivotal role of free sugars reemphasized. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 1341–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8th Edition. 2015. Available online: https://health.gov/our-work/nutrition-physical-activity/dietary-guidelines/previous-dietary-guidelines/2015 (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- EFSAPanel on Nutrition, N.F.; Allergens, F.; Turck, D.; Bohn, T.; Castenmiller, J.; de Henauw, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Knutsen, H.K.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; et al. Tolerable upper intake level for dietary sugars. EFSA J. 2022, 20, e07074. [Google Scholar]

- Rippe, J.M.; Sievenpiper, J.L.; Lê, K.-A.; White, J.S.; Clemens, R.; Angelopoulos, T.J. What is the appropriate upper limit for added sugars consumption? Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, R.K.; Appel, L.J.; Brands, M.; Howard, B.V.; Lefevre, M.; Lustig, R.H.; Sacks, F.; Steffen, L.M.; Wylie-Rosett, J. Dietary sugars intake and cardiovascular health: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2009, 120, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Policy Statement and Recommended Actions for Lowering Sugar Intake and Reducing Prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes and Obesity in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. 2016. Available online: https://applications.emro.who.int/dsaf/EMROPUB_2016_en_18687.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Strategy on Nutrition for the Eastern Mediterranean Region 2020–2030; World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean: Cairo, Egypt, 2019; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/330059/9789290222996-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Regional Framework for Action on Obesity Prevention 2019–2023; World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean: Cairo, Egypt, 2019; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/325833/EMROPUB_2019_en_22319.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Santos, J.A.; Tekle, D.; Rosewarne, E.; Flexner, N.; Cobb, L.; Al-Jawaldeh, A.; Kim, W.J.; Breda, J.; Whiting, S.; Campbell, N. A systematic review of salt reduction initiatives around the world: A midterm evaluation of progress towards the 2025 global non-communicable diseases salt reduction target. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 1768–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jawaldeh, A.; Taktouk, M.; Chatila, A.; Naalbandian, S.; Al-Thani, A.-A.M.; Alkhalaf, M.M.; Almamary, S.; Barham, R.; Baqadir, N.M.; Binsunaid, F.F. Salt reduction initiatives in the Eastern Mediterranean Region and evaluation of progress towards the 2025 global target: A systematic review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jawaldeh, A.; Taktouk, M.; Chatila, A.; Naalbandian, S.; Abdollahi, Z.; Ajlan, B.; Al Hamad, N.; Alkhalaf, M.M.; Almamary, S.; Alobaid, R. A systematic review of trans fat reduction initiatives in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 771492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Fiscal Policies to Promote Healthy Diets: Policy Brief; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240049543 (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Knowledge for Policy-European Commission. Implemented Policies to Address Sugars Intake. Available online: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/health-promotion-knowledge-gateway/sugars-sweeteners-10_en (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Krieger, J.; Bleich, S.N.; Scarmo, S.; Ng, S.W. Sugar-sweetened beverage reduction policies: Progress and promise. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2021, 42, 439–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandevijvere, S.; Vanderlee, L. Effect of formulation, labelling, and taxation policies on the nutritional quality of the food supply. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2019, 8, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharib, N.; Rasheed, P. Energy and macronutrient intake and dietary pattern among school children in Bahrain: A cross-sectional study. Nutr. J. 2011, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, L.; Hwalla, N.; Al Zahraa Chokor, F.; Naja, F.; O’Neill, L.; Jomaa, L. Food and nutrient intake of school-aged children in Lebanon and their adherence to dietary guidelines and recommendations. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jomaa, L.; Hamamji, S.; Kharroubi, S.; Diab-El-Harakeh, M.; Chokor, F.A.; Nasreddine, L. Dietary intakes, sources, and determinants of free sugars amongst Lebanese children and adolescents: Findings from two national surveys. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 2655–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasreddine, L.; Chamieh, M.C.; Ayoub, J.; Hwalla, N.; Sibai, A.M.; Naja, F. Sex disparities in dietary intake across the lifespan: The case of Lebanon. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamamji, S.E. Intakes and Sources of Fat, Free Sugars and Salt among Lebanese Children and Adolescents. Master’s Thesis, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nasreddine, L.; Ayoub, J.J.; Hachem, F.; Tabbara, J.; Sibai, A.M.; Hwalla, N.; Naja, F. Differences in dietary intakes among Lebanese adults over a decade: Results from two national surveys 1997–2008/2009. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansour, M.; Tamim, H.; Nasreddine, L.; El Khoury, C.; Hwalla, N.; Chaaya, M.; Farhat, A.; Sibai, A.M. Prevalence and associations of behavioural risk factors with blood lipids profile in Lebanese adults: Findings from WHO STEPwise NCD cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2019, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health-Sudan; World Health Organization. Sudan STEPwise Survey for Non-Communicable Disease Risk Factors 2016 Report. 2016. Available online: https://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/steps/Sudan_STEPwise_SURVEY_final_2016.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Central Statistics Organization. The National Risk and Vulnerability Assessment 2011–2012 (Afghanistan Living Conditions Survey); Afghanistan, 2014. Available online: https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/afghanistan/assessment/national-risk-and-vulnerability-assessment-20112012 (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Eini-Zinab, H.; Sobhani, S.R.; Rezazadeh, A. Designing a healthy, low-cost and environmentally sustainable food basket: An optimisation study. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 24, 1952–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkurd, R.A.; Fares, M.A.A.; Takruri, H.R. Trends of the intakes of energy, macronutrients and their food sources in Jordan. Saudi Soc. Food Nutr. J. 2022, 6, 40–54. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Pakistan. Household Integrated Economic Survey (HIES) 2018-19; Pakistan Bureau of Statistics: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2020; Available online: https://phkh.nhsrc.pk/sites/default/files/2021-07/Household%20Integrated%20Economic%20Survey%20Pakistan%202018-19.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Naeeni, M.M.; Jafari, S.; Fouladgar, M.; Heidari, K.; Farajzadegan, Z.; Fakhri, M.; Karami, P.; Omidi, R. Nutritional knowledge, practice, and dietary habits among school children and adolescents. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 5, S171–S178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazerifar, F.; Karajibani, M.; Dashipour, A.R. Evaluation of dietary intake and food patterns of adolescent girls in sistan and baluchistan province, Iran. Funct. Foods Health Dis. 2012, 2, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thana’Y, A.; Tayyem, R.F.; Takruri, H.R. Nutrient Intakes among Jordanian Adolescents Based on Gender and Body Mass Index. Int. J. Child Health Nutr. 2020, 9, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Collison, K.S.; Zaidi, M.Z.; Subhani, S.N.; Al-Rubeaan, K.; Shoukri, M.; Al-Mohanna, F.A. Sugar-sweetened carbonated beverage consumption correlates with BMI, waist circumference, and poor dietary choices in school children. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huew, R.; Maguire, A.; Waterhouse, P.; Moynihan, P. Nutrient intake and dietary patterns of relevance to dental health of 12-year-old Libyan children. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 1107–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouzes, C.M.C.; Darcel, N.; Tome, D.; Dao, M.C.; Bourdet-Sicard, R.; Holmes, B.A.; Lluch, A. Urban Egyptian Women Aged 19-30 Years Display Nutrition Transition-Like Dietary Patterns, with High Energy and Sodium Intakes, and Insufficient Iron, Vitamin D, and Folate Intakes. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fami, H.S.; Veerabhadraiah, V.; Nath, K.G. Nutritional status of rural women in relation to their participation in mixed farming in the Tafresh area of Iran. Food Nutr. Bull. 2002, 23, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stene, L.C.M.; Giacaman, R.; Abdul-Rahim, H.; Husseini, A.; Norum, K.R.; Holmboe-Ottesen, G. Food consumption patterns in a Palestinian West Bank population. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 53, 953–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Awadi, S.; Rawashdeh, S.; Talafha, M.; Bani-Issa, J.; Alkadiri, M.A.S.; Al Zoubi, M.S.; Hussein, E.; Fattah, F.A.; Bashayreh, I.H.; Al-Saghir, M. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the Jordanian eating and nutritional habits. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09585. [Google Scholar]

- Jomaa, L.; Hwalla, N.; Chokor, F.A.Z.; Naja, F.; O’Neill, L.; Nasreddine, L. Food consumption patterns and nutrient intakes of infants and young children amidst the nutrition transition: The case of Lebanon. Nutr. J. 2022, 21, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjelloun, S. Nutrition transition in Morocco. Public Health Nutr. 2002, 5, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, L.M.; Naja, F.A.; Hwalla, N.C.; Ali, H.I.; Mohamad, M.N.; Chokor, F.A.Z.S.; Chehade, L.N.; O’Neill, L.M.; Kharroubi, S.A.; Ayesh, W.H. Total Usual Nutrient Intakes and Nutritional Status of United Arab Emirates Children (< 4 Years): Findings from the Feeding Infants and Toddlers Study (FITS) 2021. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2022, 6, nzac080. [Google Scholar]

- Takruri, H.; ALjaraedah, T.; Tayyem, R. Food and nutrient intakes from school canteens and markets nearby schools among students aged 14-18 in Jordan. Nutr. Food Sci. 2021, 52, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatila, H.; Baroudi, M.; El Sayed Ahmad, R.; Chehab, R.; Forman, M.R.; Abbas, N.; Faris, M.; Naja, F. Impact of Ramadan fasting on dietary intakes among healthy adults: A year-round comparative study. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 689788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]