Time-Restricted Eating Regimen Differentially Affects Circulatory miRNA Expression in Older Overweight Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants Recruitment

2.2. Intervention

2.3. Sample Collection

2.4. miRNA Expression Profiling and Analyses

2.5. Bioinformatic Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Differentially Expressed miRNAs

3.2. miRNA Target Genes and Pathways

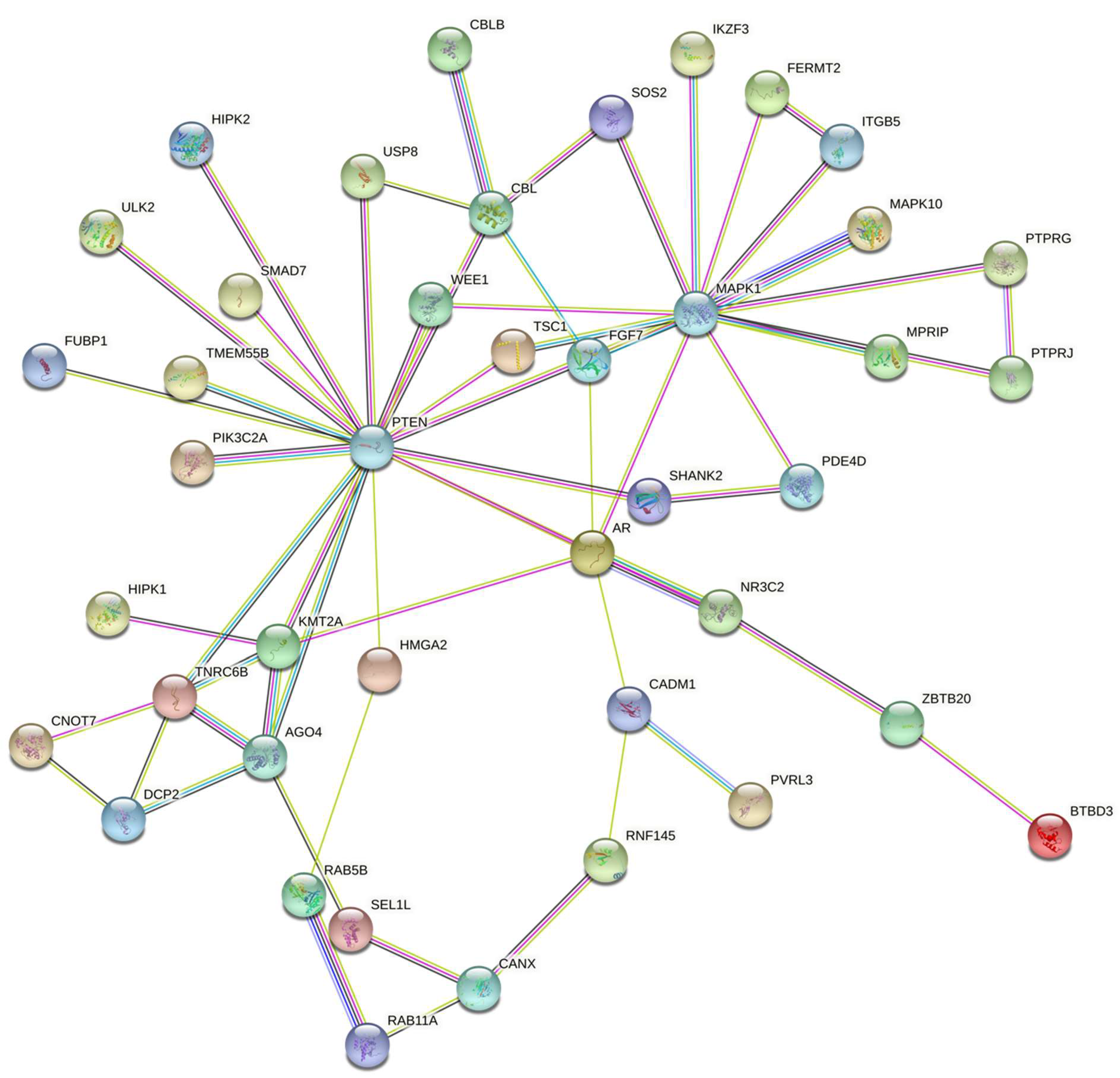

3.3. miRNA Target Interaction

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patikorn, C.; Roubal, K.; Veettil, S.K.; Chandran, V.; Pham, T.; Lee, Y.Y.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Varady, K.A.; Chaiyakunapruk, N. Intermittent Fasting and Obesity-Related Health Outcomes: An Umbrella Review of Meta-analyses of Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2139558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, B.-J.; Liao, S.-R.; Huang, W.-X.; Huang, C.; Liu, H.S.; Shen, W.-Z. Intermittent fasting therapy promotes insulin sensitivity by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome in rat model. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 5299–5309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhutani, S.; Klempel, M.C.; Berger, R.A.; Varady, K.A. Improvements in coronary heart disease risk indicators by alternate-day fasting involve adipose tissue modulations. Obesity 2010, 18, 2152–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malinowski, B.; Zalewska, K.; Węsierska, A.; Sokołowska, M.M.; Socha, M.; Liczner, G.; Pawlak-Osińska, K.; Wiciński, M. Intermittent fasting in cardiovascular disorders—an overview. Nutrients 2019, 11, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, M.P.; Longo, V.D.; Harvie, M. Impact of intermittent fasting on health and disease processes. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 39, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Cabo, R.; Mattson, M.P. Effects of intermittent fasting on health, aging, and disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2541–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cienfuegos, S.; Gabel, K.; Kalam, F.; Ezpeleta, M.; Wiseman, E.; Pavlou, V.; Lin, S.; Oliveira, M.L.; Varady, K.A. Effects of 4- and 6-h Time-Restricted Feeding on Weight and Cardiometabolic Health: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Adults with Obesity. Cell Metab. 2020, 32, 366–378.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.; Kang, J.; Kim, S.H.; Chung, H.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Yu, J.M.; Cho, S.T.; Oh, C.-M.; Kim, T. Beneficial Effects of Time-Restricted Eating on Metabolic Diseases: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, S.D.; Lee, S.A.; Donahoo, W.T.; McLaren, C.; Manini, T.; Leeuwenburgh, C.; Pahor, M. The Effects of Time Restricted Feeding on Overweight, Older Adults: A Pilot Study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, P.; Heilbronn, L.K. Time-Restricted Eating: Benefits, Mechanisms, and Challenges in Translation. iScience 2020, 23, 101161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, S.D.; Moehl, K.; Donahoo, W.T.; Marosi, K.; Lee, S.A.; Mainous, A.G., 3rd; Leeuwenburgh, C.; Mattson, M.P. Flipping the Metabolic Switch: Understanding and Applying the Health Benefits of Fasting. Obesity 2018, 26, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogure, A.; Uno, M.; Ikeda, T.; Nishida, E. The microRNA machinery regulates fasting-induced changes in gene expression and longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 11300–11309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Segura, L.; Abreu-Goodger, C.; Hernandez-Mendoza, A.; Dimitrova Dinkova, T.D.; Padilla-Noriega, L.; Perez-Andrade, M.E.; Miranda-Rios, J. High-throughput profiling of Caenorhabditis elegans starvation-responsive microRNAs. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebert, L.F.R.; MacRae, I.J. Regulation of microRNA function in animals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Guo, X. The clinical potential of circulating microRNAs in obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oses, M.; Margareto Sanchez, J.; Portillo, M.P.; Aguilera, C.M.; Labayen, I. Circulating miRNAs as Biomarkers of Obesity and Obesity-Associated Comorbidities in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrier, J.F.; Derghal, A.; Mounien, L. MicroRNAs in Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. Cells 2019, 8, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.-s.; Jin, J.-p.; Wang, J.-q.; Zhang, Z.-g.; Freedman, J.H.; Zheng, Y.; Cai, L. miRNAS in cardiovascular diseases: Potential biomarkers, therapeutic targets and challenges. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2018, 39, 1073–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, J.V.; Heintz-Buschart, A.; Ghosal, A.; Wampach, L.; Etheridge, A.; Galas, D.; Wilmes, P. Sources and functions of extracellular small RNAs in human circulation. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2016, 36, 301–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, A.; Tandon, M.; Alevizos, I.; Illei, G.G. The majority of microRNAs detectable in serum and saliva is concentrated in exosomes. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadi, H.; Ekstrom, K.; Bossios, A.; Sjostrand, M.; Lee, J.J.; Lotvall, J.O. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomou, T.; Mori, M.A.; Dreyfuss, J.M.; Konishi, M.; Sakaguchi, M.; Wolfrum, C.; Rao, T.N.; Winnay, J.N.; Garcia-Martin, R.; Grinspoon, S.K. Adipose-derived circulating miRNAs regulate gene expression in other tissues. Nature 2017, 542, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Withers, S.B.; Dewhurst, T.; Hammond, C.; Topham, C.H. MiRNAs as novel adipokines: Obesity-related circulating MiRNAs influence chemosensitivity in cancer patients. Non-Coding RNA 2020, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumortier, O.; Hinault, C.; Van Obberghen, E. MicroRNAs and metabolism crosstalk in energy homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2013, 18, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, S.H.; van Dam, S.; Craig, T.; Tacutu, R.; O’Toole, A.; Merry, B.J.; de Magalhães, J.P. Transcriptome analysis in calorie-restricted rats implicates epigenetic and post-translational mechanisms in neuroprotection and aging. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.; Dhahbi, J.M.; Atamna, H.; Clark, J.P.; Colman, R.J.; Anderson, R.M. Caloric restriction impacts plasma micro RNA s in rhesus monkeys. Aging Cell 2017, 16, 1200–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lee, E.K.; Jeong, H.O.; Bang, E.J.; Kim, C.H.; Mun, J.Y.; Noh, S.; Gim, J.-A.; Kim, D.H.; Chung, K.W.; Yu, B.P. The involvement of serum exosomal miR-500-3p and miR-770-3p in aging: Modulation by calorie restriction. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 5578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, P.M.; Barczak, A.J.; DeHoff, P.; Srinivasan, S.; Etheridge, A.; Galas, D.; Das, S.; Erle, D.J.; Laurent, L.C. Comparison of reproducibility, accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of miRNA quantification platforms. Cell Rep. 2019, 29, 4212–4222.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sticht, C.; De La Torre, C.; Parveen, A.; Gretz, N. miRWalk: An online resource for prediction of microRNA binding sites. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Li, X.; Hu, H. TarPmiR: A new approach for microRNA target site prediction. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 2768–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Franceschini, A.; Wyder, S.; Forslund, K.; Heller, D.; Huerta-Cepas, J.; Simonovic, M.; Roth, A.; Santos, A.; Tsafou, K.P. STRING v10: Protein–protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D447–D452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Likas, A.; Vlassis, N.; Verbeek, J.J. The global k-means clustering algorithm. Pattern Recognit. 2003, 36, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Zhu, X.; Xia, H. MiR-2467 is a Potential Marker for Prediction of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Pregnancy. Clin. Lab. 2020, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Wei, J.; Hao, Y.; Lan, J.; Li, W.; Weng, J.; Li, M.; Su, C.; Li, B.; Mo, M. Long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 02570 promotes nasopharyngeal carcinoma progression by adsorbing microRNA miR-4649-3p thereby upregulating both sterol regulatory element binding protein 1, and fatty acid synthase. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 7119–7130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, G. MicroRNA-301a-3p promotes triple-negative breast cancer progression through downregulating MEOX2. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 22, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Gao, H.; Wang, G.; Miao, Y.; Jiang, K.; Zhang, K.; Wu, J. Higher miR-543 levels correlate with lower STK31 expression and longer pancreatic cancer survival. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 9632–9640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S.; Manaf, R.A.; Mahmud, A. Comparison of time-restricted feeding and Islamic fasting: A scoping review. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2019, 25, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madkour, M.I.; El-Serafi, A.T.; Jahrami, H.A.; Sherif, N.M.; Hassan, R.E.; Awadallah, S.; Faris, M.e.A.-I.E. Ramadan diurnal intermittent fasting modulates SOD2, TFAM, Nrf2, and sirtuins (SIRT1, SIRT3) gene expressions in subjects with overweight and obesity. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 155, 107801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madkour, M.I.; Malhab, L.J.B.; Abdel-Rahman, W.M.; Abdelrahim, D.N.; Saber-Ayad, M.; Faris, M.E. Ramadan Diurnal Intermittent Fasting Is Associated With Attenuated FTO Gene Expression in Subjects With Overweight and Obesity: A Prospective Cohort Study. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, 741811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faris, M.e.A.-I.E.; Jahrami, H.A.; Obaideen, A.A.; Madkour, M.I. Impact of diurnal intermittent fasting during Ramadan on inflammatory and oxidative stress markers in healthy people: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Nutr. Intermed. Metab. 2019, 15, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rooij, E.; Purcell, A.L.; Levin, A.A. Developing microRNA therapeutics. Circ. Res. 2012, 110, 496–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.Y.; Chen, J.; He, L.; Stiles, B.L. PTEN: Tumor Suppressor and Metabolic Regulator. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tee, A.R.; Fingar, D.C.; Manning, B.D.; Kwiatkowski, D.J.; Cantley, L.C.; Blenis, J. Tuberous sclerosis complex-1 and -2 gene products function together to inhibit mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-mediated downstream signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 13571–13576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.S.; Gopalappa, R.; Kim, S.H.; Ramakrishna, S.; Lee, M.; Kim, W.I.; Kim, J.; Park, S.M.; Lee, J.; Oh, J.H.; et al. Somatic Mutations in TSC1 and TSC2 Cause Focal Cortical Dysplasia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 100, 454–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachari, M.; Ganley, I.G. The mammalian ULK1 complex and autophagy initiation. Essays Biochem. 2017, 61, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherniya, M.; Butler, A.E.; Barreto, G.E.; Sahebkar, A. The effect of fasting or calorie restriction on autophagy induction: A review of the literature. Ageing Res. Rev. 2018, 47, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| miRNA Name | log2 Fold Change | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| miR-2467-3p | −0.41 | 0.002 |

| miR-4649-5p | −0.42 | 0.005 |

| miR-4513 | 0.40 | 0.015 |

| miR-3132 | −0.32 | 0.021 |

| miR-411-5p | 0.35 | 0.024 |

| miR-7162-3p | 0.31 | 0.027 |

| miR-301a-3p | −0.32 | 0.028 |

| miR-5682 | 0.36 | 0.028 |

| miR-19a-5p | −0.31 | 0.032 |

| miR-543 | −0.33 | 0.036 |

| miR-495-3p | −0.30 | 0.037 |

| miR-4761-3p | −0.28 | 0.038 |

| miR-623 | 0.29 | 0.044 |

| miR-4303 | 0.31 | 0.045 |

| Name | Genes | Adjusted p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| ErbB_signaling_pathway | CAMK2G; MAPK10; CBLB; MAPK1; CBL; SOS2 | 0.002 |

| Ras_signaling_pathway | GRIN2A; RAB5B; MAPK10; FGF7; MAPK1; RALBP1; RASGRF2; SOS2 | 0.006 |

| mTOR_signaling_pathway | PTEN; TSC1; ULK2; LRP6; MAPK1; SOS2 | 0.006 |

| Insulin_signaling_pathway | TSC1; MAPK10; CBLB; MAPK1; CBL; SOS2 | 0.006 |

| Pathways_in_cancer | AR; PTEN; ARHGEF12; CAMK2G; MAPK10; FGF7; LRP6; MAPK1; CBL; RALBP1; SKP1; SOS2 | 0.006 |

| cAMP_signaling_pathway | GRIN2A; PDE3A; PDE4D; CAMK2G; MAPK10; MAPK1 | 0.014 |

| Autophagy | PTEN; TSC1; ULK2; MAPK10; MAPK1 | 0.014 |

| Regulation_of_actin_cytoskeleton | ENAH; ARHGEF12; ITGB5; FGF7; MAPK1; SOS2 | 0.014 |

| Proteoglycans_in_cancer | ARHGEF12; CAMK2G; ITGB5; MAPK1; CBL; SOS2 | 0.014 |

| Breast_cancer | PTEN; FGF7; LRP6; MAPK1; SOS2 | 0.014 |

| Cellular_senescence | PTEN; TSC1; HIPK2; HIPK1; MAPK1 | 0.0153 |

| Tuberculosis | ARHGEF12; CAMK2G; RAB5B; MAPK10; MAPK1 | 0.0218 |

| Focal_adhesion | PTEN; MAPK10; ITGB5; MAPK1; SOS2 | 0.0294 |

| Salmonella_infection | RAB5B; MAPK10; MAPK1; SKP1; GCC2 | 0.0332 |

| Human_immunodeficiency_virus_1_infection | TNFRSF1B; WEE1; MAPK10; MAPK1; SKP1 | 0.0332 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saini, S.K.; Singh, A.; Saini, M.; Gonzalez-Freire, M.; Leeuwenburgh, C.; Anton, S.D. Time-Restricted Eating Regimen Differentially Affects Circulatory miRNA Expression in Older Overweight Adults. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1843. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14091843

Saini SK, Singh A, Saini M, Gonzalez-Freire M, Leeuwenburgh C, Anton SD. Time-Restricted Eating Regimen Differentially Affects Circulatory miRNA Expression in Older Overweight Adults. Nutrients. 2022; 14(9):1843. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14091843

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaini, Sunil K., Arashdeep Singh, Manisha Saini, Marta Gonzalez-Freire, Christiaan Leeuwenburgh, and Stephen D. Anton. 2022. "Time-Restricted Eating Regimen Differentially Affects Circulatory miRNA Expression in Older Overweight Adults" Nutrients 14, no. 9: 1843. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14091843

APA StyleSaini, S. K., Singh, A., Saini, M., Gonzalez-Freire, M., Leeuwenburgh, C., & Anton, S. D. (2022). Time-Restricted Eating Regimen Differentially Affects Circulatory miRNA Expression in Older Overweight Adults. Nutrients, 14(9), 1843. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14091843