Association between Dietary Habits, Food Attitudes, and Food Security Status of US Adults since March 2020: A Cross-Sectional Online Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

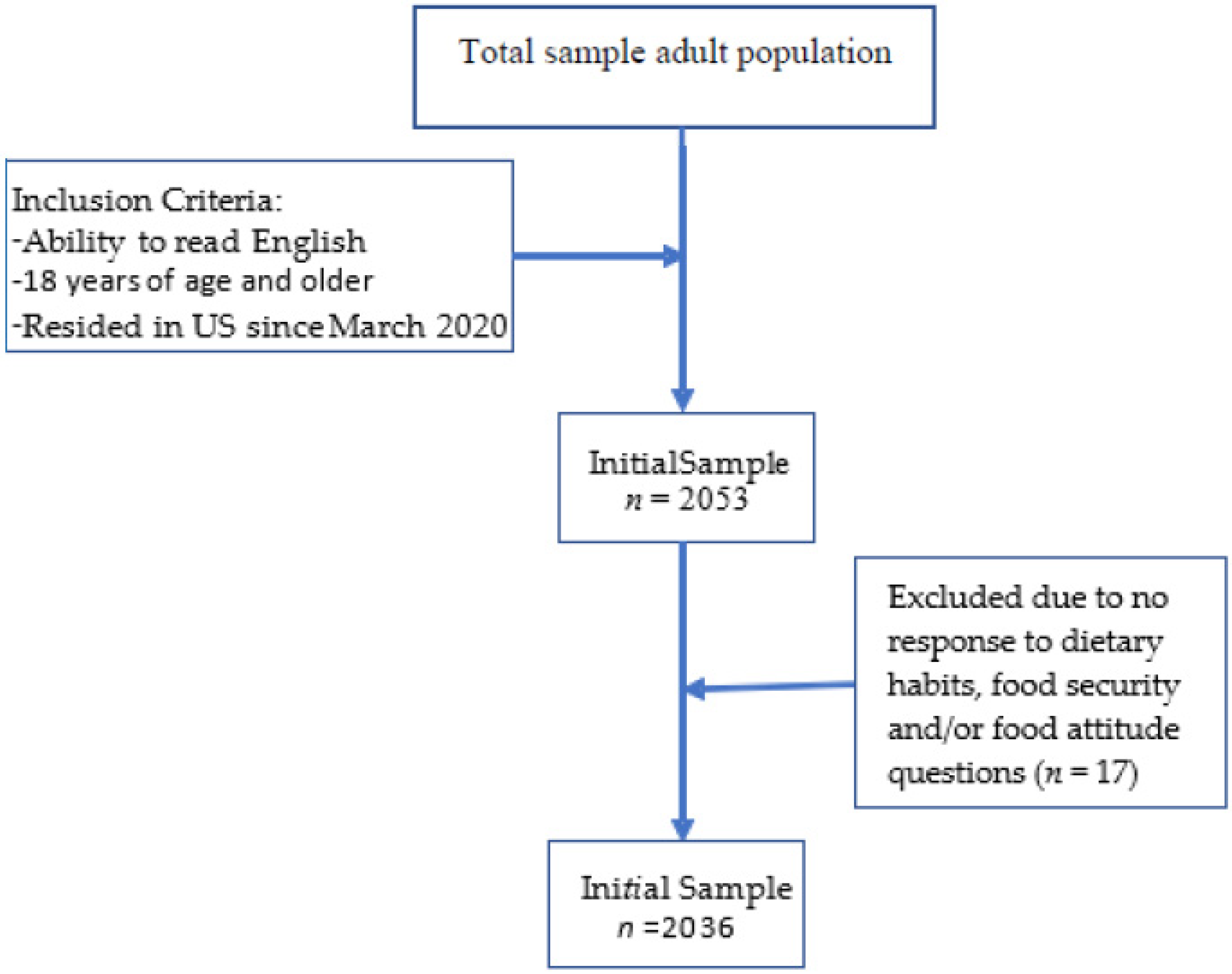

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Survey

2.2.1. Lifestyle Habits

2.2.2. Dietary Habits

2.2.3. Food Attitudes

2.2.4. Food Security

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

Health Characteristics and Anthropometrics

3.2. Dietary Habits

3.3. Association between Food Security Status and Food Attitudes on Dietary Habits

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control. COVID-19 Mortality and Overview. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/mortality-overview.htm (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- Ahn, S.; Norwood, F.B. Measuring Food Insecurity during the COVID-19 Pandemic of Spring 2020. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2021, 43, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, A.; Tasci, M.; Yan, J. The Unemployment Cost of COVID-19: How High and How Long? Econ. Comment. 2020, 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. The Employment Situation—September 2022. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2022).

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Food Price Indexes and Data Collection. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2020/article/the-impact-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-food-price-indexes-and-data-collection.htm (accessed on 9 July 2022).

- O’Connell, M.; de Paula, Á.; Smith, K. Preparing for a Pandemic: Spending Dynamics and Panic Buying during the COVID-19 First Wave. Fisc. Stud. 2021, 42, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehberger, M.; Kleih, A.K.; Sparke, K. Panic Buying in Times of Coronavirus (COVID-19): Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior to Understand the Stockpiling of Nonperishable Food in Germany. Appetite 2021, 161, 105118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bin Zarah, A.; Enriquez-Marulanda, J.; Andrade, J.M. Relationship between Dietary Habits, Food Attitudes and Food Security Status among Adults Living within the United States Three Months Post-Mandated Quarantine: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheikh Ismail, L.; Hashim, M.; Mohamad, M.N.; Hassan, H.; Ajab, A.; Stojanovska, L.; Jarrar, A.H.; Hasan, H.; Abu Jamous, D.O.; Saleh, S.T.; et al. Dietary Habits and Lifestyle During Coronavirus Pandemic Lockdown: Experience From Lebanon. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górnicka, M.; Drywień, M.E.; Zielinska, M.A.; Hamułka, J. Dietary and Lifestyle Changes during COVID-19 and the Subsequent Lockdowns among Polish Adults: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey PlifeCOVID-19 Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidor, A.; Rzymski, P. Dietary Choices and Habits during COVID-19 Lockdown: Experience from Poland. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzo, L.D.; Gualtieri, P.; Cinelli, G.; Bigioni, G.; Soldati, L.; Attinà, A.; Bianco, F.F.; Caparello, G.; Camodeca, V.; Carrano, E.; et al. Psychological Aspects and Eating Habits during COVID-19 Home Confinement: Results of Ehlc-COVID-19 Italian Online Survey. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.; Tripathy, S.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, N. Study of Knowledge, Attitude, Anxiety & Perceived Mental Healthcare Need in Indian Population during COVID-19 Pandemic. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020, 51, 102083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarmozzino, F.; Visioli, F. COVID-19 and the Subsequent Lockdown Modified Dietary Habits of Almost Half the Population in an Italian Sample. Foods 2020, 9, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamarche, B.; Brassard, D.; Lapointe, A.; Laramée, C.; Kearney, M.; Côté, M.; Bélanger-Gravel, A.; Desroches, S.; Lemieux, S.; Plante, C. Changes in Diet Quality and Food Security among Adults during the COVID-19-Related Early Lockdown: Results from NutriQuébec. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 113, 984–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyrväinen, O.; Karjaluoto, H. Online Grocery Shopping before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Meta-Analytical Review. Telemat. Inform. 2022, 71, 101839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, B.; Acharya, T. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Its Effect on Mental Health in USA—A Review with Some Coping Strategies. Psychiatr. Q. 2020, 91, 1135–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.; Levkovich, N. COVID-19 and Mental Health in America: Crisis and Opportunity? Fam. Syst. Health 2020, 38, 482–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahrami, H.; BaHammam, A.S.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Saif, Z.; Faris, M.; Vitiello, M.V. Sleep Problems during the COVID-19 Pandemic by Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2021, 17, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesi, K.; Mclaughlin, P.W. COVID-19 Working Paper: The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Food-Away-From-Home Spending; Economic Research Service, Report; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, K.L.; Yenerall, J.; Chen, X.; Yu, T.E. US Consumers’ Online Shopping Behaviors and Intentions during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2021, 53, 416–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, X. COVID-19 and Restaurant Demand: Early Effects of the Pandemic and Stay-at-Home Orders. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 13, 3809–3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenarides, L.; Grebitus, C.; Lusk, J.L.; Printezis, I. Food Consumption Behavior during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Agribusiness 2021, 37, 44–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Researchmatch.org. 2020 ReseachMatch and Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Available online: https://www.researchmatch.org/ (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Eating Habits Questionnaire. Available online: http://rtips.cancer.gov/rtips/viewProduct.do?viewMode=product&productId=173387 (accessed on 26 September 2020).

- Gearhardt, A.N.; Corbin, W.R.; Brownell, K.D. Preliminary Validation of the Yale Food Addiction Scale. Appetite 2009, 52, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickel, G.; Nord, M.; Price, C.; Hamilton, W.; Cook, J. Guide to Measuring Household Food Security. Available online: https://alliancetoendhunger.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/USDA-guide-to-measuring-food-security.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Centers for Disease Control. Defining Overweight and Obesity. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/defining.html (accessed on 21 October 2020).

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, I. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Alomari, M.A.; Khabour, O.F.; Alzoubi, K.H. Changes in Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior amid Confinement: The Bksq-COVID-19 Project. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 1757–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavrakas, P.J. Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly-Shah, V.N. Factors Influencing Healthcare Provider Respondent Fatigue Answering a Globally Administered In-App Survey. PeerJ 2017, 2017, e3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hingle, M.D.; Kandiah, J.; Maggi, A. Practice Paper of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Selecting Nutrient-Dense Foods for Good Health. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 1473–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Department of Agriculture Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020–2025, 9th ed.; United States Department of Agriculture Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Smith, S.; Malinak, D.; Chang, J.; Perez, M.; Perez, S.; Settlecowski, E.; Rodriggs, T.; Hsu, M.; Abrew, A.; Aedo, S. Implementation of a Food Insecurity Screening and Referral Program in Student-Run Free Clinics in San Diego, California. Prev. Med. Rep. 2017, 5, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JMP®, Version 16; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2021.

- Cavazza, N.; Guidetti, M.; Butera, F. Ingredients of Gender-Based Stereotypes about Food. Indirect Influence of Food Type, Portion Size and Presentation on Gendered Intentions to Eat. Appetite 2015, 91, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavazza, N.; Guidetti, M.; Butera, F. Portion Size Tells Who I Am, Food Type Tells Who You Are: Specific Functions of Amount and Type of Food in Same- and Opposite-Sex Dyadic Eating Contexts. Appetite 2017, 112, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.K.; Concepcion, R.Y.; Lee, H.; Cardinal, B.J.; Ebbeck, V.; Woekel, E.; Readdy, R.T. An Examination of Sex Differences in Relation to the Eating Habits and Nutrient Intakes of University Students. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2012, 44, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassen, T.; El Bilali, H.; Allahyari, M.S.; Kamel, I.M.; Ben Ismail, H.; Debbabi, H.; Sassi, K. Gendered Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Food Behaviors in North Africa: Cases of Egypt, Morocco, and Tunisia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Chang, B.P.I.; Hristov, H.; Pravst, I.; Profeta, A.; Millard, J. Changes in Food Consumption During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Analysis of Consumer Survey Data From the First Lockdown Period in Denmark, Germany, and Slovenia. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 635859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callinan, S.; Mojica-Perez, Y.; Wright, C.J.C.; Livingston, M.; Kuntsche, S.; Laslett, A.M.; Room, R.; Kuntsche, E. Purchasing, Consumption, Demographic and Socioeconomic Variables Associated with Shifts in Alcohol Consumption during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2021, 40, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szajnoga, D.; Klimek-Tulwin, M.; Piekut, A. COVID-19 Lockdown Leads to Changes in Alcohol Consumption Patterns. Results from the Polish National Survey. J. Addict. Disord. 2021, 39, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyprianidou, M.; Chrysostomou, S.; Christophi, C.A.; Giannakou, K. Change of Dietary and Lifestyle Habits during and after the COVID-19 Lockdown in Cyprus: An Analysis of Two Observational Studies. Foods 2022, 11, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caso, D.; Guidetti, M.; Capasso, M.; Cavazza, N. Finally, the Chance to Eat Healthily: Longitudinal Study about Food Consumption during and after the First COVID-19 Lockdown in Italy. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 95, 104275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Gómez, C.; De La Higuera, M.; Rivas-García, L.; Diaz-Castro, J.; Moreno-Fernandez, J.; Lopez-Frias, M. Has COVID-19 Changed the Lifestyle and Dietary Habits in the Spanish Population after Confinement? Foods 2021, 10, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, B.; Benson, T.; McCloat, A.; Mooney, E.; Elliott, C.; Dean, M.; Lavelle, F. Changes in Consumers’ Food Practices during the COVID-19 Lockdown, Implications for Diet Quality and the Food System: A Cross-Continental Comparison. Nutrients 2021, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, D.; Rešetar, J.; Gajdoš Kljusurić, J.; Panjkota Krbavčić, I.; Vranešić Bender, D.; Rodríguez-Pérez, C.; Ruíz-López, M.D.; Šatalić, Z. Cooking at Home and Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet During the COVID-19 Confinement: The Experience From the Croatian COVIDiet Study. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 617721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, A.A.; Partridge, S.R. Nutritional Qualities of Commercial Meal Kit Subscription Services in Australia. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; Vi, L.H.; Beer, S.; Ermolaev, V.A. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Food Consumption at Home and Away: An Exploratory Study of English Households. Socioecon. Plann. Sci. 2022, 82, 101125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A. Food Prices and Spending. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/ag-and-food-statistics-charting-the-essentials/food-prices-and-spending/ (accessed on 9 January 2022).

- Vindegaard, N.; Benros, M.E. COVID-19 Pandemic and Mental Health Consequences: Systematic Review of the Current Evidence. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2020, 89, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poelman, M.P.; Gillebaart, M.; Schlinkert, C.; Dijkstra, S.C.; Derksen, E.; Mensink, F.; Hermans, R.C.J.; Aardening, P.; de Ridder, D.; de Vet, E. Eating Behavior and Food Purchases during the COVID-19 Lockdown: A Cross-Sectional Study among Adults in the Netherlands. Appetite 2021, 157, 105002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, K.E.; Badiger, A.; Roe, B.E.; Shu, Y.; Qi, D. Consumer Behavior during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Analysis of Food Purchasing and Management Behaviors in U.S. Households through the Lens of Food System Resilience. Socioecon. Plann. Sci. 2022, 82, 101107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, A.; Li, J.; Ke, Y.; Huo, S.; Ma, Y. Food and Nutrition Related Concerns Post Lockdown during COVID-19 Pandemic and Their Association with Dietary Behaviors. Foods 2021, 10, 2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Althubaiti, A. Information Bias in Health Research: Definition, Pitfalls, and Adjustment Methods. J. Multidiscip. Health 2016, 9, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Y1 = b0 + b1 × 1 + b2X2 + … + bkXk | |

|---|---|

| where | |

| Y1 represents | Dietary Habits |

| b0, b1, and bk represent | Estimate regression parameters |

| X1, X2, and Xk represent | k predictors (demographics, lifestyle habits, food attitudes, and food security status) |

| Variables | No. of Responses (%) a |

|---|---|

| Sex | n = 2004 |

| Male | 414 (20.7%) |

| Female | 1545 (77.1%) |

| Other | 45 (2.2%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | n = 1983 |

| African American | 74 (3.7%) |

| Asian | 59 (3.0%) |

| White | 1696 (85.5%) |

| Hispanic | 87 (4.4%) |

| Native American | 12 (0.6%) |

| Other | 55 (2.8%) |

| Age | n = 2012 |

| 18–24 years | 159 (7.9%) |

| 25–29 years | 191 (9.5%) |

| 30–49 years | 675 (33.5%) |

| 50–59 years | 333 (16.6%) |

| 60–69 years | 397 (19.7%) |

| >70 years | 257 (12.8%) |

| Education level | n = 2011 |

| No schooling completed | 1 (0.0%) |

| Some high school, no diploma | 7 (0.3%) |

| High school graduate, diploma, or equivalent (GED b) | 62 (3.1%) |

| Some college credit, no degree | 241 (12.0%) |

| Trade/technical/vocational training | 78 (3.9%) |

| Associate degree | 148 (7.4%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 692 (34.4%) |

| Master’s degree | 572 (28.4%) |

| Professional degree | 74 (3.7%) |

| Doctorate degree | 136 (6.8%) |

| Current employment status | n = 2012 |

| Full time | 915 (45.5%) |

| Part-time | 285 (14.2%) |

| Unemployed | 275 (13.7%) |

| Other | 537 (26.7%) |

| Marital status | n = 2008 |

| Married | 968 (48.2%) |

| Single | 618 (30.8%) |

| Widowed | 75 (3.7%) |

| Divorced | 267 (13.3%) |

| Other | 80 (4.0%) |

| People live in the household besides yourself | n = 2036 |

| None | 386 (19.0%) |

| 1 | 808 (39.7%) |

| 2 | 358 (17.6%) |

| 3 | 250 (12.3%) |

| 4 | 123 (6.0%) |

| 5 or more | 68 (3.3%) |

| Did not respond | 43 (2.1%) |

| Currently staying at home x% of the time | n = 2015 |

| Less than 25% | 413 (20.5%) |

| 50–75% | 781 (38.8%) |

| 75–95% | 783 (38.9%) |

| Never left the house | 38 (1.9%) |

| Residence | n = 2010 |

| New England (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Vermont) | 80 (4.0%) |

| Mid-Atlantic (New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania) | 235 (11.7%) |

| South Atlantic (Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, Washington DC, West Virginia) | 431 (21.4%) |

| East North Central (Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin) | 382 (19.0%) |

| East South Central (Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee) | 222 (11.0%) |

| West North Central (Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota) | 174 (8.7%) |

| West South Central (Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas) | 90 (4.5%) |

| Mountain (Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming) | 145 (7.2%) |

| Pacific (Alaska, California, Hawaii, Oregon, Washington) | 251 (12.5%) |

| Variables | No. of Responses (%) a |

|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) b | n = 2012 |

| <18 | 60 (3.0%) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 794 (39.5%) |

| 25–29.9 | 580 (28.8%) |

| >30 | 578 (28.7%) |

| Self-reported Weight change | n = 2035 |

| No change | 639 (31.4%) |

| Increased | 908 (44.6%) |

| Decreased | 488 (24.0%) |

| Activity | n = 2016 |

| No change | 626 (31.1%) |

| Increased | 537 (26.6%) |

| Decreased | 853 (42.3%) |

| Tried a diet | n = 2034 |

| No | 1279 (62.9%) |

| Yes | 755 (37.1%) |

| Nutritional supplement intake | n = 2032 |

| No | 1399 (68.8%) |

| Yes | 633 (31.2%) |

| Supplements currently taking | n = 600 |

| Multi-vitamin | 42 (7.0%) |

| Vitamin B complex | 1 (0.2%) |

| Vitamin C | 4 (0.7%) |

| Vitamin D | 26 (4.3%) |

| Other | 39 (6.5%) |

| Two supplements | 138 (23.0%) |

| Three supplements | 94 (15.7%) |

| Four or more supplements | 256 (42.7%) |

| Medical conditions | n = 1403 |

| Cancer | 14 (1.0%) |

| Depression | 234 (16.7%) |

| Diabetes (high blood sugar) | 30 (2.1%) |

| Diverticulosis/Diverticulitis | 8 (0.6%) |

| Gastric reflux | 49 (3.5%) |

| Heart disease | 87 (6.2%) |

| IBS/D c | 26 (1.9%) |

| Liver disease (cirrhosis, fatty liver) | 2 (0.1%) |

| Lung disease | 10 (0.7%) |

| Nausea/Vomiting | 3 (0.2%) |

| Other | 178 (12.7%) |

| 2 conditions | 410 (29.2%) |

| 3 or more conditions | 352 (25.1%) |

| Food/Beverage Items | Increased (%) | Decreased (%) | No Change/Never Consumed (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Milk and non-milk | 411 (20.2%) | 247 (12.1%) | 1378 (67.7%) |

| Margarine or butter | 212 (10.4%) | 286 (14.0%) | 1538 (75.5%) |

| Fruit | 647 (31.8%) | 333 (16.4%) | 1056 (51.9%) |

| Fruit juice | 229 (11.2%) | 263 (12.9%) | 1544 (75.8%) |

| Non-starchy vegetables | 676 (33.2%) | 248 (12.2%) | 1112 (54.6%) |

| Vegetable or tomato juice | 97 (4.8%) | 131 (6.4%) | 1808 (88.8%) |

| Eggs, chicken, or turkey | 583 (28.6%) | 243 (11.9%) | 1210 (59.4%) |

| Beef, pork, or lamb | 226 (11.1%) | 562 (27.6%) | 1248 (61.3%) |

| Processed meats | 502 (24.7%) | 313 (15.4%) | 1221 (60.0%) |

| Fish and shellfish | 424 (20.8%) | 267 (13.1%) | 1345 (66.1%) |

| Cold breakfast cereals | 298 (14.6%) | 395 (19.4%) | 1343 (66.0%) |

| White bread | 321 (15.8%) | 289 (14.2%) | 1426 (70.0%) |

| Dark bread | 260 (12.8%) | 246 (12.1%) | 1530 (75.1%) |

| French fried potatoes | 406 (19.9%) | 318 (15.6%) | 1312 (64.4%) |

| Potatoes | 404 (19.8%) | 254 (12.5%) | 1378 (67.7%) |

| Starchy vegetables | 388 (19.1%) | 205 (10.1%) | 1443 (70.9%) |

| White rice or pasta | 306 (15%) | 500 (24.6%) | 1230 (60.4%) |

| Brown rice or whole-grain pasta | 384 (18.9%) | 178 (8.7%) | 1474 (72.4%) |

| Potato chips or other salty snacks | 373 (18.3%) | 642 (31.5%) | 1021 (50.1%) |

| Nuts or seeds | 691 (33.9%) | 181 (8.9%) | 1164 (57.2%) |

| Peanut butter or other nut butter | 512 (25.1%) | 222 (10.9%) | 1302 (63.9%) |

| Sweets | 318 (15.6%) | 783 (38.5%) | 935 (45.9%) |

| Oils | 313 (15.4%) | 109 (5.4%) | 1614 (79.3%) |

| Water | 855 (42.0%) | 145 (7.1%) | 1036 (50.9%) |

| Coffee or Tea | 182 (8.9%) | 719 (35.3%) | 1135 (55.7%) |

| Immune enhancing beverages | 288 (14.1%) | 41 (2.0%) | 1707 (83.8%) |

| Beer or wine | 308 (15.1%) | 454 (22.3%) | 1274 (62.6%) |

| Hard liquor | 281 (13.8%) | 337 (16.6%) | 1418 (69.6%) |

| Low-calorie carbonated beverages | 163 (8.0%) | 296 (14.5%) | 1577 (77.5%) |

| Carbonated beverages | 241 (11.8%) | 241 (11.8%) | 1554 (76.3%) |

| Total Dietary Habits Score | Coef. | Std. Err. | t | p < |t| * | 95% Conf. Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food attitudes ∗ Food security | 10.35 | 0.27 | 11.08 | <0.001 | 0.73 | 1.04 |

| Food attitudes score | 1.11 | 0.09 | 11.84 | <0.001 | 0.93 | 1.29 |

| Food security score | 0.53 | 0.09 | 5.72 | <0.001 | 0.35 | 0.71 |

| Sex: female | −1.97 | 0.52 | −3.81 | <0.001 | −2.98 | −0.95 |

| Ethnicity | −0.05 | 0.29 | −0.16 | 0.87 | −0.62 | 0.52 |

| Residence | −0.15 | 0.10 | −1.59 | 0.11 | −0.34 | 0.04 |

| Education | −0.15 | 0.14 | −1.05 | 0.29 | −0.44 | 0.13 |

| Employment | 0.10 | 0.29 | 0.46 | 0.65 | −0.31 | 0.50 |

| Marital status | 0.23 | 0.19 | 1.20 | 0.23 | −0.15 | 0.61 |

| % of time spent at home | −0.31 | 0.31 | −0.98 | 0.33 | −0.92 | 0.31 |

| Age range | −0.16 | 0.20 | −0.80 | 0.424 | −0.56 | 0.23 |

| Household size | −0.19 | 0.18 | −1.06 | 0.291 | −0.53 | 0.16 |

| BMI | −0.01 | 0.27 | −0.04 | 0.969 | −0.53 | 0.51 |

| Weight change | 0.32 | 0.32 | 1.00 | 0.32 | −0.31 | 0.96 |

| Medical conditions | 0.13 | 0.05 | 2.62 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.22 |

| Tried a diet | 1.53 | 0.49 | 3.10 | <0.001 | 0.56 | 2.49 |

| Nutritional supplement intake | 2.55 | 0.50 | 5.10 | <0.001 | 1.57 | 3.54 |

| Attributes | Coef. | Std. Err. | t | p < |t| * | 95% Conf. Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical activity | 1.24 | 0.32 | 3.87 | <0.001 | 0.61 | 1.87 |

| Dining at restaurants | 0.17 | 0.35 | 0.47 | 0.63 | −0.52 | 0.86 |

| Preparing/cooking meals in the home | 0.99 | 0.30 | 3.35 | <0.001 | 0.41 | 1.57 |

| Meal kit services | 1.18 | 0.36 | 3.30 | <0.001 | 0.48 | 1.88 |

| Take-out/delivery of meals from restaurants | 1.06 | 0.37 | 2.86 | <0.001 | 0.33 | 1.78 |

| Grocery shopping in the store | 1.14 | 0.32 | 3.58 | <0.001 | 0.52 | 1.76 |

| Grocery shopping online | −0.14 | 0.24 | −0.59 | 0.56 | −0.62 | 0.34 |

| Reading/studying | 0.81 | 0.25 | 3.20 | <0.001 | 0.31 | 1.30 |

| Sleeping hours and quality | 1.09 | 0.30 | 3.66 | <0.001 | 0.50 | 1.67 |

| Smoking (cigarettes, cigars, hookah) | 2.13 | 0.54 | 3.93 | <0.001 | 1.07 | 3.20 |

| Socializing outside the home | 0.06 | 0.46 | 0.14 | 0.89 | −0.84 | 0.96 |

| Using electronic devices | 2.04 | 0.53 | 3.87 | <0.001 | 1.01 | 3.08 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bin Zarah, A.; Schneider, S.T.; Andrade, J.M. Association between Dietary Habits, Food Attitudes, and Food Security Status of US Adults since March 2020: A Cross-Sectional Online Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4636. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14214636

Bin Zarah A, Schneider ST, Andrade JM. Association between Dietary Habits, Food Attitudes, and Food Security Status of US Adults since March 2020: A Cross-Sectional Online Study. Nutrients. 2022; 14(21):4636. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14214636

Chicago/Turabian StyleBin Zarah, Aljazi, Sydney T Schneider, and Jeanette Mary Andrade. 2022. "Association between Dietary Habits, Food Attitudes, and Food Security Status of US Adults since March 2020: A Cross-Sectional Online Study" Nutrients 14, no. 21: 4636. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14214636

APA StyleBin Zarah, A., Schneider, S. T., & Andrade, J. M. (2022). Association between Dietary Habits, Food Attitudes, and Food Security Status of US Adults since March 2020: A Cross-Sectional Online Study. Nutrients, 14(21), 4636. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14214636