State Agencies’ Perspectives on Planning and Preparing for WIC Online Ordering Implementation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Respondents

2.2. Survey and Measures

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Analyses

2.4.1. Assessing Risk Factors for Facing WIC Online Ordering Barriers

2.4.2. Reasons for Not Responding to the Funding Opportunity

2.4.3. Qualitative Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. WIC State Agency Characteristics

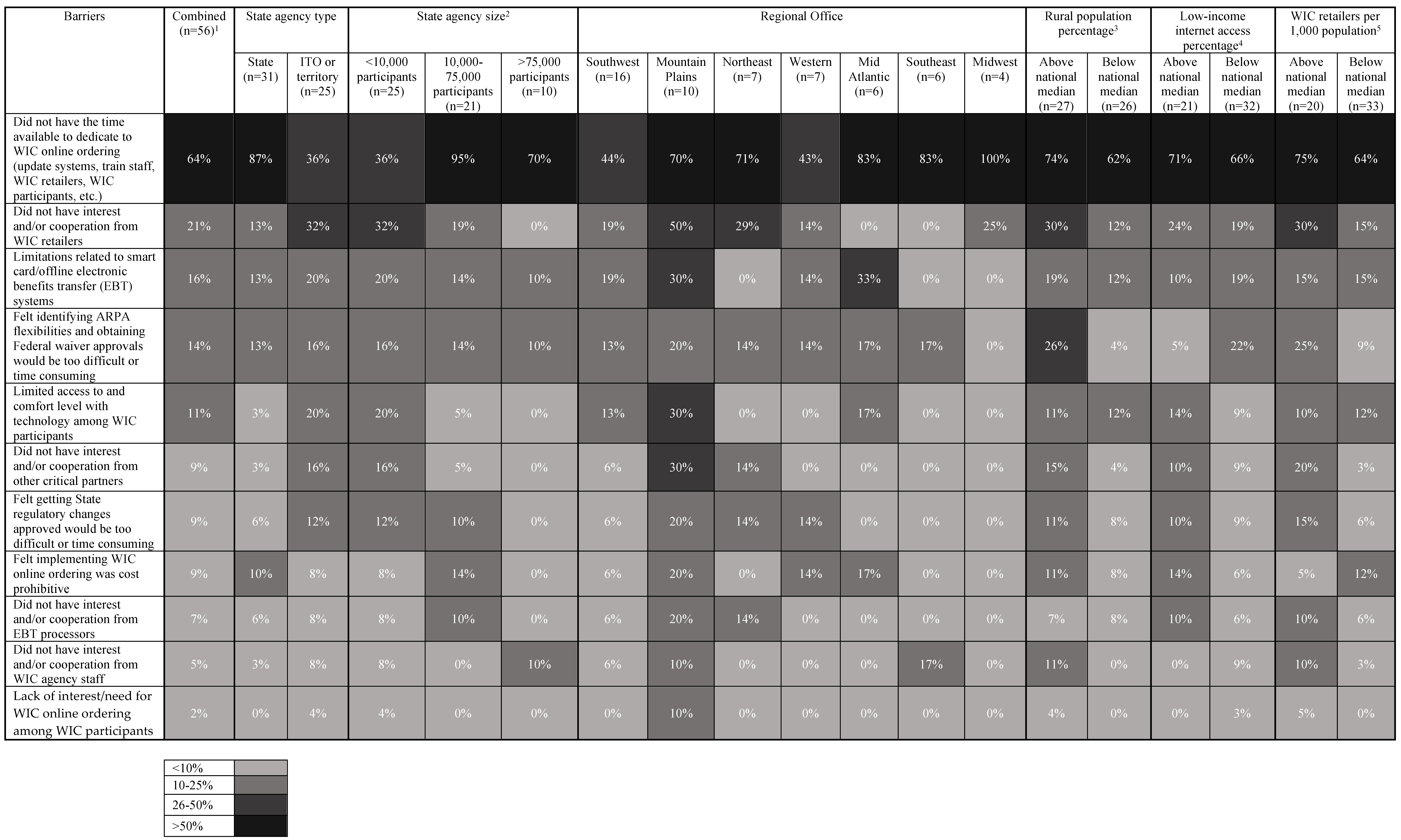

3.2. Barriers to Implementing WIC Online Ordering

3.3. Reasons for Not Applying to WIC Online Ordering Funding Opportunity

3.4. Best Practices and Strategies for WIC Online Ordering

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Importance | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Did not have the time available to dedicate to WIC online ordering (update systems, train staff, WIC retailers, WIC participants, etc.) | ||

| “Not a factor” | 14 | 25 |

| “Minor factor” | 6 | 11 |

| “Major factor” | 36 | 64 |

| Did not have interest and/or cooperation from WIC retailers | ||

| “Not a factor” | 42 | 75 |

| “Minor factor” | 2 | 4 |

| “Major factor” | 12 | 21 |

| Limitations related to smart card/offline electronic benefits transfer (EBT) systems | ||

| “Not a factor” | 41 | 73 |

| “Minor factor” | 6 | 11 |

| “Major factor” | 9 | 16 |

| Felt identifying ARPA flexibilities and obtaining Federal waiver approvals would be too difficult or time consuming | ||

| “Not a factor” | 33 | 59 |

| “Minor factor” | 15 | 27 |

| “Major factor” | 8 | 1 |

| Limited access to and comfort level with technology among WIC participants | ||

| “Not a factor” | 42 | 75 |

| “Minor factor” | 8 | 14 |

| “Major factor” | 6 | 11 |

| Did not have interest and/or cooperation from other critical partners | ||

| “Not a factor” | 46 | 8 |

| “Minor factor” | 5 | 9 |

| “Major factor” | 5 | 9 |

| Felt getting State regulatory changes approved would be too difficult or time consuming | ||

| “Not a factor” | 41 | 73 |

| “Minor factor” | 10 | 18 |

| “Major factor” | 5 | 9 |

| Felt implementing WIC online ordering was cost prohibitive | ||

| “Not a factor” | 38 | 68 |

| “Minor factor” | 13 | 23 |

| “Major factor” | 5 | 9 |

| Did not have interest and/or cooperation from EBT processors | ||

| “Not a factor” | 48 | 86 |

| “Minor factor” | 4 | 7 |

| “Major factor” | 4 | 7 |

| Did not have interest and/or cooperation from WIC agency staff | ||

| “Not a factor” | 49 | 88 |

| “Minor factor” | 4 | 7 |

| “Major factor” | 3 | 5 |

| Lack of interest/need for WIC online ordering among WIC participants | ||

| “Not a factor” | 49 | 88 |

| “Minor factor” | 6 | 11 |

| “Major factor” | 1 | 2 |

| Reason Selected | Considered Applying, But Did Not (n = 25) | Did Not Consider Applying (n = 33) | Combined (n = 58) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Did not have the capacity to implement and/or manage a WIC online ordering project | 76% | 67% | 71% |

| Did not have staff capacity and/or expertise on staff to develop a proposal | 60% | 52% | 55% |

| Did not have the capacity to prepare adequate implementation plans needed for the proposal | 48% | 45% | 47% |

| Did not have enough time to prepare and submit a proposal (i.e., time between funding announcement and deadline was too short) | 40% | 33% | 36% |

| Did not have the technology to implement a WIC online ordering project | 20% | 39% | 31% |

| Did not receive commitment from a WIC retailer | 24% | 21% | 22% |

| Felt identifying ARPA flexibilities and obtaining Federal waiver approvals would be too difficult or time consuming | 28% | 18% | 22% |

| Did not find requirements of participation in the sub-grant project appealing (too burdensome, not interesting, etc.) | 20% | 18% | 19% |

| Did not receive commitment from an EBT processor | 16% | 12% | 14% |

| Did not have enough information about the application process | 8% | 12% | 10% |

| Did not think that enough funding was available (i.e., award dollar amount was too low) | 16% | 3% | 9% |

| Did not need the funding | 4% | 6% | 5% |

References

- WIC Program Participation and Costs. Food and Nutrition Service. Available online: https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/wisummary-5.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- About WIC—WIC at a Glance. Food and Nutrition Service. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/about-wic-glance (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- WIC Food Packages—Maximum Monthly Allowances. Food and Nutrition Service. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/wic-food-packages-maximum-monthly-allowances (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- About WIC: How WIC Helps. Food and Nutrition Service. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/about-wic-how-wic-helps (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Gray, K.F.; Balch-Crystal, E.; Giannarelli, L.; Johnson, P.; National- and State-Level Estimates of WIC Eligibility and WIC Program Reach in 2019 Final Report. Insight Policy Research. Available online: https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/WICEligibles2019-Volume1-revised.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Blueprint for WIC Online Ordering. Gretchen Swanson Center for Nutrition. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58a4dda16a49633eac5e02a1/t/60c8ea51296905287a9420eb/1623779922155/Blueprint+for+WIC+Online+Ordering.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- WIC—Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) and Management Information Systems (MIS). Food and Nutrition Service. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/wic-electronic-benefits-transfer-ebt (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Making WIC Work Better: Strategies to Reach More Women and Children and Strengthen Benefits Use. Food Research & Action Center. Available online: https://frac.org/research/resource-library/making-wic-work-better-strategies-to-reach-more-women-and-children-and-strengthen-benefits-use (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Ammerman, A.; De Marco, M.; Harding, M.; Hartman, T.; Rhode, J.; Buying Wisely and Well: Managing WIC Food Costs While Improving the WIC Customer’s Shopping Experience. BECR Center. Available online: https://hpdp.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/976/2021/02/BECR_BuyingWiselyandWell.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Chauvenet, C.; De Marco, M.; Barnes, C.; Ammerman, A.S. WIC recipients in the retail environment: A qualitative study assessing customer experience and satisfaction. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 119, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Tang, C.; McLaughlin, P.W.; Diggs, L. Individual and store characteristics associated with brand choices in select food category redemptions among WIC participants in Virginia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batool, M.; Ghulam, H.; Hayat, M.H.; Naeem, M.Z.; Ejaz, A.; Imran, Z.A.; Spulbar, C.; Birau, R.; Gorun, T.H. How COVID-19 has shaken the sharing economy? An analysis using Google trends data. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraz. 2020, 34, 2374–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, M.; McElrone, M.; Steeves, E.T.A. Feasibility and acceptability of a “Click & Collect” WIC online ordering pilot. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 2464–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagisetty, P.; Flamm, L.; Rak, S.; Landgraf, J.; Heisler, M.; Forman, J. A multi-stakeholder evaluation of the Baltimore City virtual supermarket program. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PART 246—Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children | Food and Nutrition Service. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/part-246%E2%80%94special-supplemental-nutrition-program-women-infants-and-children (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- WIC Supports Online Ordering and Transactions in WIC. Food and Nutrition Service. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/supports-online-ordering-transactions (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Calloway, E.E.; Steeves, E.T.A.; Nitto, A.M.; Hill, J.L. A mixed-methods study of perceived implementation challenges for online ordering and transactions with the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). Forthcoming.

- Hu, M. FFVP CFD Pilot—State: Evaluation of the Pilot Project for Canned, Frozen, or Dried (CFD) Fruits and Vegetables in the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program (FFVP). Available online: https://omb.report/icr/201503-0584-006/doc/54643501 (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Qualtrics, X.M.; —Experience Management Software. Qualtrics. Available online: https://www.qualtrics.com/ (accessed on 19 October 2022).

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.L.; Calloway, E.E.; Nitto, A.M.; Steeves, E.T.A. Application of a Delphi technique to identify the challenges for adoption, implementation, and maintenance of WIC online ordering across various systems and stakeholders. Forthcoming.

- Magness, A.; Williams, K.; Papa, F.; Garza, A.; Okyere, D.; Nisar, H.; Bajowski, F.; Singer, B. Third National Survey of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Participants (NSWP-III) (Summary). Food and Nutrition Service. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/third-national-survey-wic-participants (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- 2010 Census Urban and Rural Classification and Urban Area Criteria. United States Census Bureau. Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/geography/guidance/geo-areas/urban-rural/2010-urban-rural.html (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Types of Computers and Internet Subscriptions. United States Census Bureau. Available online: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=broadband&g=0100000US%240400000&tid=ACSST1Y2019.S2801 (accessed on 19 October 2022).

- Food Environment Atlas. USDA Economic Research Service. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-environment-atlas/ (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; L. Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Microsoft Excel Spreadsheet Software. Microsoft 365. Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/excel (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Srivastava, P.; Hopwood, N. A practical iterative framework for qualitative data analysis. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2009, 8, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WIC Data Tables Food and Nutrition Service. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/wic-program (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Grants Food and Nutrition Service. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/fm/grant-opportunities?page=0 (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- WIC Program: Average Monthly Benefit Per Person. Food and Nutrition Service. Available online: https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/25wifyavgfd$-5.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Magness, A.; Williams, K.; Gordon, E.; Morrissey, N.; Papa, F.; Garza, A.; Okyere, D.; Nisar, H.; Bajowski, F.; Singer, B.; Third National Survey of WIC Participants (NSWP-III) Brief Report 7: WIC Participant Use of Other Assistance Programs. Food and Nutrition Service 2021. Available online: https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/NSWP-III-BriefReport7.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Nearly a Third of Children Who Receive SNAP Participate in Two or More Additional Programs. United States Census Bureau. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/06/most-children-receiving-snap-get-at-least-one-other-social-safety-net-benefit.html (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- WIC EBT Detail Status Report. Food and Nutrition Service. Available online: https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/April2022WICEBTDetailStatusReport.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Ritchie, L.; Lee, D.; Sallack, L.; Chauvenet, C.; Machell, G.; Kim, L.; Song, L.; Whaley, S.; Multi-State WIC Participant Satisfaction Survey: Learning from Program Adaptations During COVID. National WIC Association; 2021:41. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/aws.upl/nwica.org/nwamulti-state-wic-participant-satisfaction-surveynationalreportfinal.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Zimmer, M.C.; Beaird, J.; Steeves, E.T.A. WIC participants’ perspectives about online ordering and technology in the WIC program. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2021, 53, 602–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, C.R.; Niculescu, M.; Guthrie, J.F.; Mancino, L. Can a better understanding of WIC customer experiences increase benefit redemption and help control program food costs? J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2018, 13, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasgow, R.E.; Vogt, T.M.; Boles, S.M. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework. Am. J. Public Health 1999, 89, 1322–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jilcott Pitts, S.B.; Ng, S.W.; Blitstein, J.L.; Gustafson, A.; Kelley, C.J.; Pandya, S.; Weismiller, H. Perceived advantages and disadvantages of online grocery shopping among Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children participants in eastern North Carolina. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Introduction Questions |

| Did your WIC State agency consider applying for the WIC Online Ordering Sub-grant funding opportunity? |

| What steps, if any, did your State agency take to assess interest and/or feasibility for pursuing the WIC Online Ordering Sub-grant Project funding opportunity? Select all that apply. |

| Is your State agency already implementing or planning to implement a WIC online ordering project? |

| What is your State agency’s anticipated timeline for starting a WIC online ordering project? |

Please indicate whether each of the following was not a factor, a minor factor, or a major factor contributing to your State agency’s decision NOT to apply for the WIC Online Ordering Sub-grant Project funding. Response options include N/A, Not a Factor, Minor Factor, Major Factor.Examples of factors assessed:

|

We are also interested in reasons for not implementing a WIC online ordering project outside of the GSCN sub-grant opportunity. Please indicate whether each of the following was not a factor, a minor factor, or a major factor contributing to your State agency’s decision NOT to implement a WIC online ordering project. Response options include N/A, Not a Factor, Minor Factor, Major Factor.Examples of factors assessed:

|

| Existing WIC Ordering Projects Block: Questions were only asked for those who responded ‘yes’ to already implementing or was planning to implement a WIC online ordering project. |

| When did your State agency start planning and implementing a WIC online ordering project? |

Select all organizations that your State agency engaged with to plan and implement your WIC online ordering project.Examples of organizations included:

|

| What steps did your State agency take to plan and prepare for your WIC online ordering project? |

| Please describe the top three challenges or barriers your State agency has faced in planning and implementing your WIC online ordering project and how you overcome those challenges. |

| Based on your experiences with your current WIC online ordering project, what key lessons learned would you like to share with other State agencies that are considering implementing their own project (e.g., important project components, beneficial implementation practices, key partnerships, etc.). |

| What conditions are necessary for your WIC online ordering project to continue successfully? |

| Thinking about the future of your WIC online ordering project, what conditions are necessary for the expansion? |

| Variable | Category | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| State agency type | State | 33 |

| ITO | 22 | |

| Territory | 3 | |

| State agency size 2 | <10,000 participants | 25 |

| 10,000–75,000 participants | 23 | |

| >75,000 participants | 10 | |

| Regional Office | Southwest | 17 |

| Mountain Plains | 10 | |

| Western | 8 | |

| Northeast | 7 | |

| Mid Atlantic | 6 | |

| Southeast | 6 | |

| Midwest | 4 | |

| Rural population percentage 3 | Above national median | 28 |

| Below national median | 27 | |

| Low-income internet access percentage 4 | Above national median | 21 |

| Below national median | 34 | |

| WIC retailers per 1000 population 5 | Above national median | 21 |

| Below national median | 34 |

| Agency Characteristic | Mean Score | SD | N | p-Value 2 | Cohen’s d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State agency type | State | 4.26 | 2.77 | 31 | 0.367 | 0.254 |

| ITO or territory | 5.40 | 5.72 | 25 | |||

| State agency size 3,4,5 | <10,000 participants | 5.40 | 5.72 | 25 | 0.372 | 0.528 |

| 10,000–75,000 participants | 4.81 | 2.86 | 21 | |||

| >75,000 participants | 3.10 | 2.28 | 10 | |||

| Regional Office 4,6 | Southwest | 3.94 | 4.68 | 16 | 0.151 | 0.938 |

| Mountain Plains | 8.50 | 5.89 | 10 | |||

| Northeast | 4.29 | 3.55 | 7 | |||

| Western | 3.43 | 3.26 | 7 | |||

| Mid Atlantic | 4.50 | 2.43 | 6 | |||

| Southeast | 3.67 | 2.34 | 6 | |||

| Midwest | 4.00 | 2.71 | 4 | |||

| Rural population percentage 7 | Above national median | 5.78 | 5.21 | 27 | 0.157 | 0.393 |

| Below national median | 4.08 | 3.20 | 26 | |||

| Low-income internet access percentage 8 | Above national median | 5.10 | 3.18 | 21 | 0.825 | 0.061 |

| Below national median | 4.84 | 5.07 | 32 | |||

| WIC retailers per 1000 population 9 | Above national median | 6.30 | 3.94 | 20 | 0.142 | 0.565 |

| Below national median | 4.12 | 3.77 | 33 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nitto, A.M.; Calloway, E.E.; Anderson Steeves, E.T.; Wieczorek Basl, A.; Papa, F.; Kersten, S.K.; Hill, J.L. State Agencies’ Perspectives on Planning and Preparing for WIC Online Ordering Implementation. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4447. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14214447

Nitto AM, Calloway EE, Anderson Steeves ET, Wieczorek Basl A, Papa F, Kersten SK, Hill JL. State Agencies’ Perspectives on Planning and Preparing for WIC Online Ordering Implementation. Nutrients. 2022; 14(21):4447. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14214447

Chicago/Turabian StyleNitto, Allison M., Eric E. Calloway, Elizabeth T. Anderson Steeves, Amy Wieczorek Basl, Francesca Papa, Sarah K. Kersten, and Jennie L. Hill. 2022. "State Agencies’ Perspectives on Planning and Preparing for WIC Online Ordering Implementation" Nutrients 14, no. 21: 4447. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14214447

APA StyleNitto, A. M., Calloway, E. E., Anderson Steeves, E. T., Wieczorek Basl, A., Papa, F., Kersten, S. K., & Hill, J. L. (2022). State Agencies’ Perspectives on Planning and Preparing for WIC Online Ordering Implementation. Nutrients, 14(21), 4447. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14214447