Diet Quality of Adolescents and Adults Who Completed the Australian Healthy Eating Quiz: An Analysis of Data over Six Years (2016–2022)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

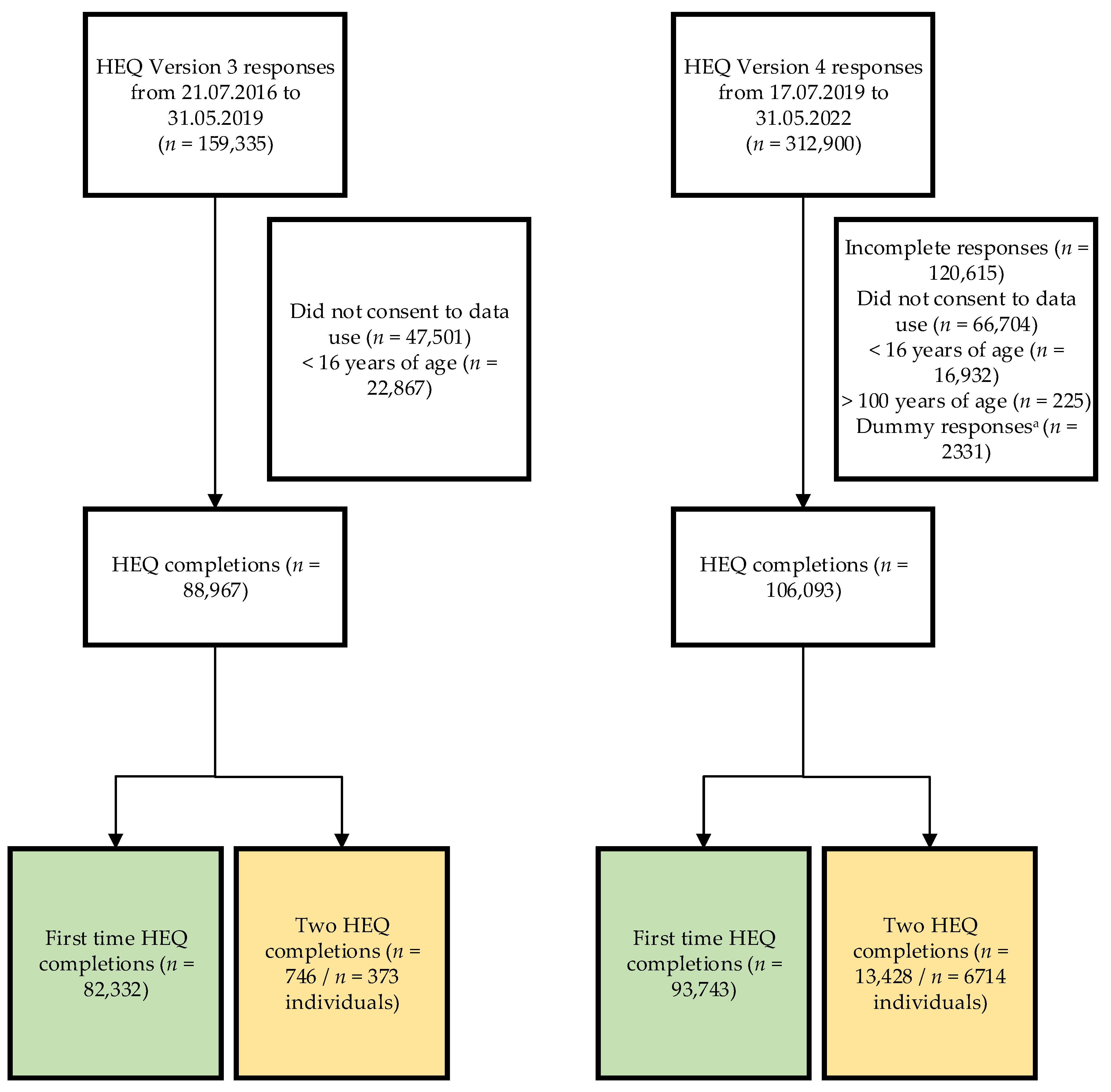

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Materials

Healthy Eating Quiz

2.3. Demographics

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Study Sample

3.2. Comparison of Healthy Eating Quiz Scores by Demographic Characteristics

3.3. Comparison of Healthy Eating Quiz Scores for Repeat Completers (n = 7087)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wirt, A.; Collins, C.E. Diet quality-what is it and does it matter? Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 2473–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hlaing-Hlaing, H.; Pezdirc, K.; Tavener, M.; James, E.L.; Hure, A. Diet Quality Indices Used in Australian and New Zealand Adults: A Systematic Review and Critical Appraisal. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwingshackl, L.; Bogensberger, B.; Hoffmann, G. Diet Quality as Assessed by the Healthy Eating Index, Alternate Healthy Eating Index, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Score, and Health Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 74–100.e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.S.; Vos, T.; Flaxman, A.D.; Danaei, G.; Shibuya, K.; Adair-Rohani, H.; Amann, M.; Anderson, H.R.; Andrews, K.G.; Aryee, M.; et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380, 2224–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, J.N.; Forder, P.M.; Haslam, R.; Hure, A.; Loxton, D.; Patterson, A.J.; Collins, C.E. Lower Vegetable Variety and Worsening Diet Quality Over Time Are Associated With Higher 15-Year Health Care Claims and Costs Among Australian Women. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 655–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, A.; Hure, A.; Burrows, T.; Jackson, J.; Collins, C. Diet quality and 10-year healthcare costs by BMI categories in the mid-age cohort of the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 31, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, K.S.; Kris-Etherton, P.M. Diet Quality Assessment and the Relationship between Diet Quality and Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health England; Food Standards Agency. National Diet and Nutrition Survey: Diet, Nutrition and Physical Activity in 2020 A Follow Up Study during COVID-19. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1019663/Follow_up_stud_2020_main_report.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Lee SH, M.L.; Park, S.; Harris, D.M.; Blanck, H.M. Adults Meeting Fruit and Vegetable Intake Recommendations—United States, 2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Health Survey: Consumption of Food Groups from the Australian Dietary Guidelines, 2011–2012. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/4364.0.55.012~2011-12~Main%20Features~Grains~16 (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Chen, P.J.; Antonelli, M. Conceptual Models of Food Choice: Influential Factors Related to Foods, Individual Differences, and Society. Foods 2020, 9, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, K.M.; Abbott, G.; Lamb, K.E.; Dullaghan, K.; Worsley, T.; McNaughton, S.A. Understanding Meal Choices in Young Adults and Interactions with Demographics, Diet Quality, and Health Behaviors: A Discrete Choice Experiment. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 2361–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, M.G.; Kestin, M.; Riddell, L.J.; Keast, R.S.; McNaughton, S.A. Diet quality in young adults and its association with food-related behaviours. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 1767–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bärebring, L.; Palmqvist, M.; Winkvist, A.; Augustin, H. Gender differences in perceived food healthiness and food avoidance in a Swedish population-based survey: A cross sectional study. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblanc, V.; Bégin, C.; Corneau, L.; Dodin, S.; Lemieux, S. Gender differences in dietary intakes: What is the contribution of motivational variables? J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 28, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grech, A.; Sui, Z.; Siu, H.Y.; Zheng, M.; Allman-Farinelli, M.; Rangan, A. Socio-Demographic Determinants of Diet Quality in Australian Adults Using the Validated Healthy Eating Index for Australian Adults (HEIFA-2013). Healthcare 2017, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, H.W.; Vadiveloo, M.K. Diet quality of vegetarian diets compared with nonvegetarian diets: A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2019, 77, 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satija, A.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Rimm, E.B.; Spiegelman, D.; Chiuve, S.E.; Borgi, L.; Willett, W.C.; Manson, J.E.; Sun, Q.; Hu, F.B. Plant-Based Dietary Patterns and Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes in US Men and Women: Results from Three Prospective Cohort Studies. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darmon, N.; Drewnowski, A. Contribution of food prices and diet cost to socioeconomic disparities in diet quality and health: A systematic review and analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2015, 73, 643–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.D.; Leung, C.W.; Li, Y.; Ding, E.L.; Chiuve, S.E.; Hu, F.B.; Willett, W.C. Trends in Diet quality Among Adults in the United States, 1999 Through 2010. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 1587–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmon, N.; Drewnowski, A. Does social class predict diet quality? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 1107–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.; McNaughton, S.A.; Rychetnik, L.; Lee, A.J. A systematic scoping review of the habitual dietary costs in low socioeconomic groups compared to high socioeconomic groups in Australia. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, W.; Ju, Y.J.; Shin, J.; Jang, S.I.; Park, E.C. Association between eating behaviour and diet quality: Eating alone vs. eating with others. Nutr. J. 2018, 17, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, N.; Fulkerson, J.; Story, M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Shared meals among young adults are associated with better diet quality and predicted by family meal patterns during adolescence. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Hannan, P.J.; Story, M.; Croll, J.; Perry, C. Family meal patterns: Associations with sociodemographic characteristics and improved dietary intake among adolescents. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2003, 103, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winpenny, E.M.; van Sluijs, E.M.F.; White, M.; Klepp, K.-I.; Wold, B.; Lien, N. Changes in diet through adolescence and early adulthood: Longitudinal trajectories and association with key life transitions. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whatnall, M.C.; Patterson, A.J.; Ashton, L.M.; Hutchesson, M.J. Effectiveness of brief nutrition interventions on dietary behaviours in adults: A systematic review. Appetite 2018, 120, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, L.M.; Sharkey, T.; Whatnall, M.C.; Williams, R.L.; Bezzina, A.; Aguiar, E.J.; Collins, C.E.; Hutchesson, J.M. Effectiveness of Interventions and Behaviour Change Techniques for Improving Dietary Intake in Young Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of RCTs. Nutrients 2019, 11, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, K.; Dyakova, M.; Wilson, N.; Ward, K.; Thorogood, M.; Brunner, E. Dietary advice for reducing cardiovascular risk (Review). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 4, CD002128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, C.A.; Ravia, J. A Systematic Review of Behavioral Interventions to Promote Intake of Fruit and Vegetables. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2011, 111, 1523–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.E.; Burrows, T.L.; Rollo, M.E.; Boggess, M.M.; Watson, J.F.; Guest, M.; Duncanson, K.; Pezdirc, K.; Hutchesson, M.J. The comparative validity and reproducibility of a diet quality index for adults: The Australian Recommended Food Score. Nutrients 2015, 7, 785–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachat, C.; Hawwash, D.; Ocke, M.C.; Berg, C.; Forsum, E.; Hornell, A.; Larsson, C.; Sonestedt, E.; Wirfalt, E.; Akesson, A.; et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology-Nutritional Epidemiology (STROBE-nut): An Extension of the STROBE Statement. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.L.; Rollo, M.E.; Schumacher, T.; Collins, C.E. Diet Quality Scores of Australian Adults Who Have Completed the Healthy Eating Quiz. Nutrients 2017, 9, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashton, L.; Williams, R.; Wood, L.; Schumacher, T.; Burrows, T.; Rollo, M.; Pezdirc, K.; Callister, R.; Collins, C. Comparison of Australian Recommended Food Score (ARFS) and Plasma Carotenoid Concentrations: A Validation Study in Adults. Nutrients 2017, 9, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/censushome.nsf/home/seifa (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- Imamura, F.; Micha, R.; Khatibzadeh, S.; Fahimi, S.; Shi, P.; Powles, J.; Mozaffarian, D. Diet quality among men and women in 187 countries in 1990 and 2010: A systematic assessment. Lancet Glob. Health 2015, 3, e132–e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, R. Fast-food and full-service restaurant consumption and daily energy and nutrient intakes in US adults. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munt, A.E.; Partridge, S.R.; Allman-Farinelli, M. The barriers and enablers of healthy eating among young adults: A missing piece of the obesity puzzle: A scoping review. Obes. Rev. 2017, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkerwi, A.; Vernier, C.; Sauvageot, N.; Crichton, G.E.; Elias, M.F. Demographic and socioeconomic disparity in nutrition: Application of a novel Correlated Component Regression approach. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e006814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelle, F.; Bucher, T.; Dean, M.; Brown, H.M.; Rollo, M.E.; Collins, C.E. Diet quality is more strongly related to food skills rather than cooking skills confidence: Results from a national cross-sectional survey. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 77, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groufh-Jacobsen, S.; Bahr Bugge, A.; Morseth, M.S.; Pedersen, J.T.; Henjum, S. Dietary Habits and Self-Reported Health Measures Among Norwegian Adults Adhering to Plant-Based Diets. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 813482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, S.; Thomas, J. Social influences on eating. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2016, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, N.; MacLehose, R.; Fulkerson, J.A.; Berge, J.M.; Story, M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Eating Breakfast and Dinner Together as a Family: Associations with Sociodemographic Characteristics and Implications for Diet Quality and Weight Status. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 1601–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, I.; Lawrence, W.; Barker, M.; Baird, J.; Dennison, E.; Sayer, A.A.; Cooper, C.; Robinson, S. What influences diet quality in older people? A qualitative study among community-dwelling older adults from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study, UK. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 2685–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whatnall, M.C.; Hutchesson, M.J.; Sharkey, T.; Haslam, R.L.; Bezzina, A.; Collins, C.E.; Tzelepis, F.; Ashton, L.M. Recruiting and retaining young adults: What can we learn from behavioural interventions targeting nutrition, physical activity and/or obesity? A systematic review of the literature. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 5686–5703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashton, L.M.; Hutchesson, M.J.; Rollo, M.E.; Morgan, P.J.; Collins, C.E. Motivators and Barriers to Engaging in Healthy Eating and Physical Activity: A Cross-Sectional Survey in Young Adult Men. Am. J. Men’s Health 2016, 11, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, J. Exploring digital health care: eHealth, mHealth, and librarian opportunities. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2021, 109, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ordovas, J.M.; Ferguson, L.R.; Tai, E.S.; Mathers, J.C. Personalised nutrition and health. BMJ 2018, 361, bmj.k2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Characteristic | Total (n = 176,075) | Version 3 (n = 82,332) | Version 4 (n = 93,743) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 124,028 (70.4) | 58,590 (71.2) | 65,438 (69.8) |

| Male | 51,300 (29.1) | 23,742 (28.8) | 27,558 (29.4) |

| Another gender identity | 747 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 747 (0.8) |

| Age groups | |||

| 16–17 years | 19,491 (11.1) | 11,719 (14.2) | 7772 (8.3) |

| 18–24 years | 48,770 (27.7) | 23,941 (29.1) | 24,829 (26.5) |

| 25–34 years | 42,112 (23.9) | 19,158 (23.3) | 22,954 (24.5) |

| 35–44 years | 23,575 (13.4) | 9688 (11.8) | 13,887 (14.8) |

| 45–54 years | 18,593 (10.6) | 7768 (9.4) | 10,825 (11.6) |

| 55–64 years | 14,545 (8.3) | 6179 (7.5) | 8366 (8.9) |

| 65–74 years | 7277 (4.1) | 3081 (3.7) | 4196 (4.5) |

| ≥75 years | 1712 (1.0) | 798 (1.0) | 914 (1.0) |

| Vegetarian | 22,360 (12.7) | 9495 (11.5) | 12,865 (13.7) |

| Number of people main meals are shared with a | |||

| Only themself | 55,502 (32.2) | 26,868 (33.4) | 28,634 (31.0) |

| With 1 other person | 61,172 (35.4) | 27,780 (34.6) | 33,392 (36.2) |

| With 2 or more other people | 55,925 (32.4) | 25,701 (32.0) | 30,224 (32.8) |

| Country of residence b | |||

| Australia | 95,407 (62.8) | 30,478 (52.4) | 64,929 (69.3) |

| Other | 56,484 (37.2) | 27,670 (47.6) | 28,814 (30.7) |

| Index of relative socio-economic advantage and disadvantage (decile) c | |||

| 1–3 (most disadvantaged) | 10,569 (14.0) | 2857 (14.0) | 7712 (14.0) |

| 4–7 | 27,918 (36.9) | 7416 (36.3) | 20,502 (37.2) |

| 8–10 (most advantaged) | 37,125 (49.1) | 10,146 (49.7) | 26,979 (48.9) |

| Demographic Characteristic | Total Score/73 | Vegetable/21 | Fruit/12 | Meat/Flesh/7 | Plant-Based Protein/6 | Grains/13 | Dairy/11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 33.9 ± 9.4 | 12.3 ± 4.3 | 5.2 ± 2.8 | 2.8 ± 1.7 | 3.0 ± 2.0 | 5.6 ± 2.3 | 3.4 ± 2.0 |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 34.5 ± 9.1 | 12.5 ± 4.1 | 5.3 ± 2.7 | 2.7 ± 1.7 | 3.1 ± 2.1 | 5.7 ± 2.3 | 3.4 ± 2.0 |

| Male | 32.6 ± 9.9 | 11.3 ± 4.5 | 4.7 ± 2.9 | 3.0 ± 1.7 | 2.8 ± 1.8 | 5.5 ± 2.3 | 3.5 ± 2.0 |

| Another gender identity | 31.5 ± 12.0 | 10.7 ± 4.9 | 4.8 ± 3.1 | 2.0 ± 1.8 | 3.8 ± 3.0 | 5.7 ± 2.7 | 3.0 ± 2.1 |

| Age groups | |||||||

| 16–17 years | 34.1 ± 10.0 | 11.1 ± 4.5 | 6.0 ± 2.9 | 2.8 ± 1.7 | 2.6 ± 1.8 | 6.0 ± 2.3 | 3.7 ± 2.1 |

| 18–24 years | 32.4 ± 9.6 | 11.0 ± 4.4 | 5.0 ± 2.8 | 2.4 ± 1.7 | 2.9 ± 2.1 | 5.7 ± 2.3 | 3.3 ± 2.1 |

| 25–34 years | 33.3 ± 9.6 | 12.1 ± 4.1 | 4.7 ± 2.6 | 2.7 ± 1.7 | 3.1 ± 2.1 | 5.7 ± 2.3 | 3.2 ± 2.0 |

| 35–44 years | 34.7 ± 9.2 | 12.9 ± 4.0 | 5.0 ± 2.7 | 2.9 ± 1.7 | 3.1 ± 2.0 | 5.7 ± 2.4 | 3.3 ± 2.0 |

| 45–54 years | 34.9 ± 9.1 | 13.2 ± 4.0 | 5.2 ± 2.8 | 3.1 ± 1.7 | 3.1 ± 1.9 | 5.3 ± 2.4 | 3.4 ± 1.9 |

| 55–64 years | 35.9 ± 8.9 | 13.7 ± 3.8 | 5.5 ± 2.7 | 3.2 ± 1.7 | 3.1 ± 1.8 | 5.2 ± 2.3 | 3.6 ± 2.0 |

| 65–74 years | 37.0 ± 8.5 | 13.9 ± 3.7 | 6.0 ± 2.6 | 3.4 ± 1.7 | 3.2 ± 1.8 | 5.2 ± 2.1 | 4.0 ± 1.9 |

| ≥75 years | 37.5 ± 9.8 | 13.5 ± 4.2 | 6.3 ± 2.7 | 3.6 ± 1.6 | 3.0 ± 1.7 | 5.4 ± 2.3 | 4.3 ± 1.9 |

| Vegetarian | 37.3 ± 9.3 | 13.2 ± 4.0 | 5.6 ± 2.7 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 6.1 ± 3.2 | 6.2 ± 2.3 | 2.7 ± 2.1 |

| Non-vegetarian | 33.4 ± 9.3 | 12.0 ± 4.3 | 5.1 ± 2.8 | 3.2 ± 1.5 | 2.6 ± 1.3 | 5.5 ± 2.3 | 3.5 ± 2.0 |

| Number of people main meals are shared with a | |||||||

| Only themself | 30.9 ± 9.6 | 10.6 ± 4.5 | 4.8 ± 2.8 | 2.3 ± 1.7 | 3.0 ± 2.1 | 5.2 ± 2.3 | 3.2 ± 2.1 |

| With 1 other person | 34.8 ± 8.8 | 12.8 ± 4.0 | 5.1 ± 2.7 | 2.9 ± 1.7 | 3.1 ± 2.1 | 5.7 ± 2.3 | 3.4 ± 2.0 |

| With 2 or more other people | 35.9 ± 9.0 | 13.0 ± 4.0 | 5.6 ± 2.8 | 3.1 ± 1.6 | 2.9 ± 1.9 | 6.0 ± 2.3 | 3.6 ± 2.0 |

| Country of residence b | |||||||

| Australia | 35.1 ± 9.0 | 13.1 ± 3.9 | 5.2 ± 2.7 | 2.9 ± 1.7 | 3.0 ± 2.2 | 5.8 ± 2.3 | 3.4 ± 1.9 |

| Other | 32.4 ± 9.6 | 11.0 ± 4.4 | 5.1 ± 2.8 | 2.6 ± 1.7 | 3.0 ± 1.9 | 5.5 ± 2.4 | 3.5 ± 2.1 |

| Index of relative socio-economic advantage and disadvantage (decile) c | |||||||

| 1–3 (most disadvantaged) | 34.1 ± 9.5 | 12.8 ± 4.2 | 5.0 ± 2.9 | 2.9 ± 1.6 | 2.8 ± 2.1 | 5.5 ± 2.3 | 3.4 ± 1.9 |

| 4–7 | 34.9 ± 9.1 | 13.1 ± 4.0 | 5.1 ± 2.8 | 2.9 ± 1.7 | 2.9 ± 2.2 | 5.7 ± 2.3 | 3.4 ± 1.9 |

| 8–10 (most advantaged) | 35.8 ± 8.7 | 13.3 ± 3.8 | 5.2 ± 2.7 | 2.9 ± 1.7 | 3.3 ± 2.2 | 5.9 ± 2.3 | 3.4 ± 1.9 |

| Demographic Characteristic | Healthy Eating Quiz Total Score a | |

|---|---|---|

| β-Coefficient | Standard Error | |

| Gender | ||

| Reference category = Female | ||

| Male | −1.89 * | 0.05 |

| Another gender identity | −2.98 * | 0.34 |

| Age groups | ||

| Reference category = 16–17 years | ||

| 18–24 years | −1.70 * | 0.08 |

| 25–34 years | −0.81 * | 0.08 |

| 35–44 years | 0.61 * | 0.09 |

| 45–54 years | 0.87 * | 0.10 |

| 55–64 years | 1.83 * | 0.10 |

| 65–74 years | 2.91 * | 0.13 |

| ≥75 years | 3.43 * | 0.24 |

| Vegetarian | ||

| Reference category = Non-vegetarian | ||

| Vegetarian | 3.89 * | 0.07 |

| Number of people main meals are shared with b | ||

| Reference category = Only themself | ||

| With 1 other person | 3.90 * | 0.05 |

| With 2 or more other people | 5.00 * | 0.06 |

| Country of residence c | ||

| Reference category = Other | ||

| Australia | 3.66 * | 0.05 |

| Index of relative socio-economic advantage and disadvantage (decile) d | ||

| Reference category = 1–3 (most disadvantaged) | ||

| 4–7 | 0.77 * | 0.10 |

| 8–10 (most advantaged) | 1.72 * | 0.10 |

| Total Score | Vegetable | Fruit | Meat/Flesh | Plant-Based Protein | Grains | Dairy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First completion | 35.3 ± 8.9 | 13.1 ± 4.0 | 5.2 ± 2.6 | 2.8 ± 1.7 | 3.5 ± 2.5 | 5.7 ± 2.2 | 3.5 ± 2.0 |

| Repeat completion | 37.7 ± 9.2 | 13.8 ± 3.9 | 5.6 ± 2.7 | 2.9 ± 1.8 | 3.8 ± 2.6 | 6.1 ± 2.2 | 3.7 ± 2.0 |

| Change in score | 2.3 ± 6.9 | 0.8 ± 3.1 | 0.4 ± 2.2 | 0.2 ± 1.5 | 0.3 ± 1.8 | 0.3 ± 2.0 | 0.2 ± 1.7 |

| Healthy Eating Quiz Category | Change in Healthy Eating Quiz Total Score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Model | Adjusted Model a | |||||

| Β-Coefficient | Standard Error | p | Β-Coefficient | Standard Error | p | |

| Reference category = ≥47 | ||||||

| 39–46 | 2.14 | 0.29 | <0.001 | 2.16 | 0.29 | <0.001 |

| 33–38 | 4.53 | 0.29 | <0.001 | 4.60 | 0.29 | <0.001 |

| <33 | 6.88 | 0.28 | <0.001 | 7.04 | 0.29 | <0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Whatnall, M.; Clarke, E.D.; Adam, M.T.P.; Ashton, L.M.; Burrows, T.; Hutchesson, M.; Collins, C.E. Diet Quality of Adolescents and Adults Who Completed the Australian Healthy Eating Quiz: An Analysis of Data over Six Years (2016–2022). Nutrients 2022, 14, 4072. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14194072

Whatnall M, Clarke ED, Adam MTP, Ashton LM, Burrows T, Hutchesson M, Collins CE. Diet Quality of Adolescents and Adults Who Completed the Australian Healthy Eating Quiz: An Analysis of Data over Six Years (2016–2022). Nutrients. 2022; 14(19):4072. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14194072

Chicago/Turabian StyleWhatnall, Megan, Erin D. Clarke, Marc T. P. Adam, Lee M. Ashton, Tracy Burrows, Melinda Hutchesson, and Clare E. Collins. 2022. "Diet Quality of Adolescents and Adults Who Completed the Australian Healthy Eating Quiz: An Analysis of Data over Six Years (2016–2022)" Nutrients 14, no. 19: 4072. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14194072

APA StyleWhatnall, M., Clarke, E. D., Adam, M. T. P., Ashton, L. M., Burrows, T., Hutchesson, M., & Collins, C. E. (2022). Diet Quality of Adolescents and Adults Who Completed the Australian Healthy Eating Quiz: An Analysis of Data over Six Years (2016–2022). Nutrients, 14(19), 4072. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14194072