Decreasing Vitamin C Intake, Low Serum Vitamin C Level and Risk for US Adults with Diabetes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Design and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Statistical Methods

3. Results

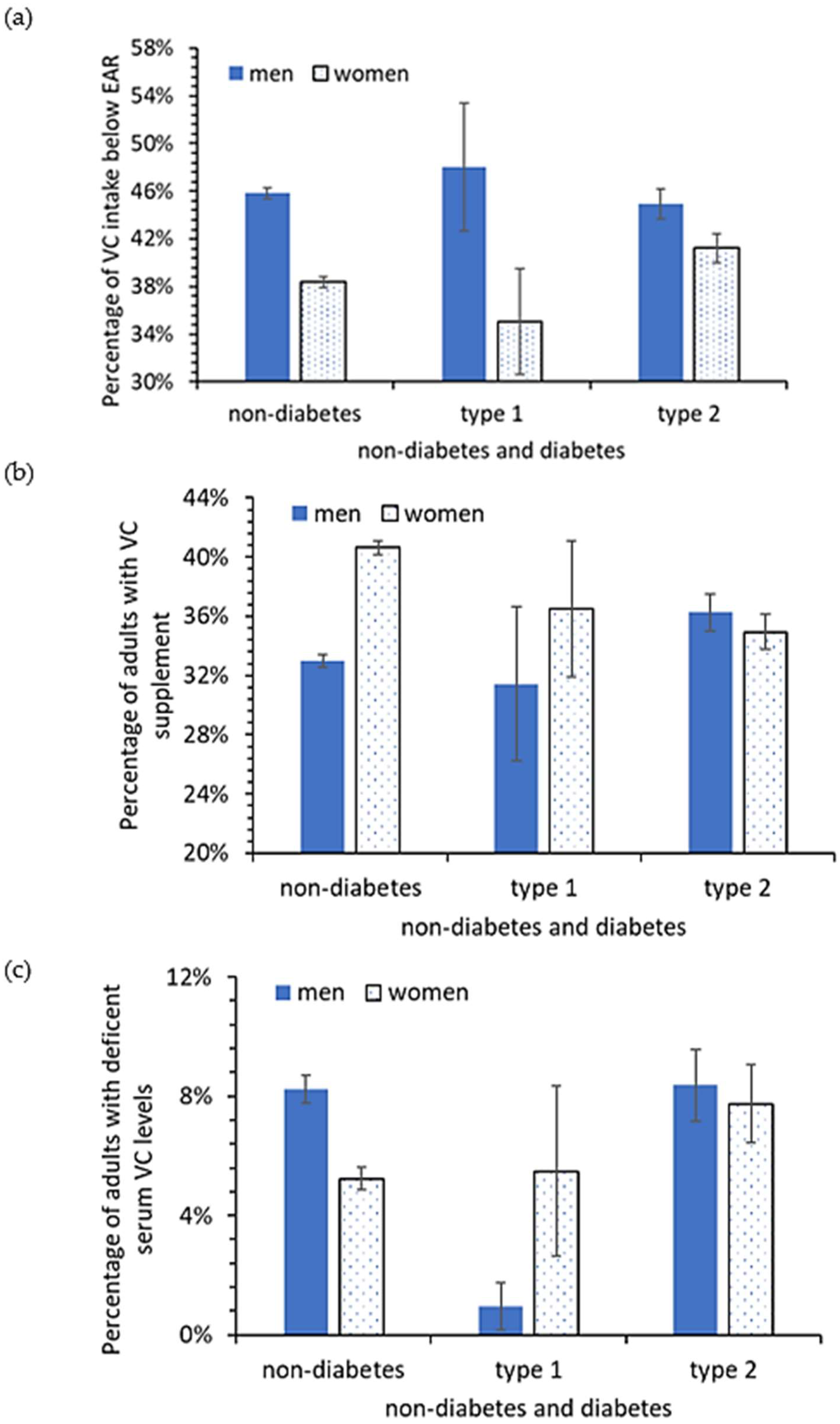

3.1. Statuses of VC Intake, Serum VC Level, Relations with Fasting Glucose and A1c

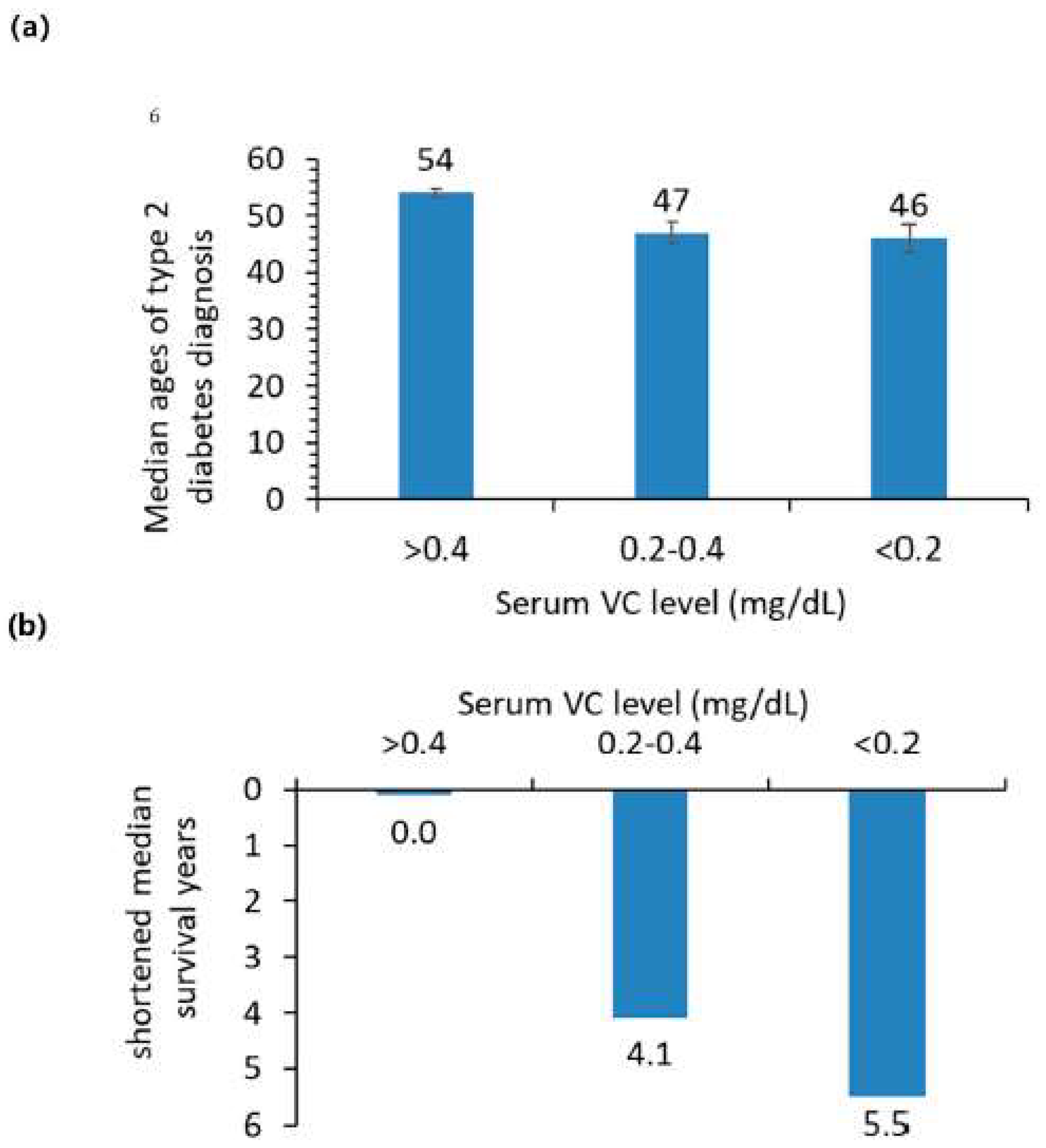

3.2. Ages of Type 2 Diabetes Diagnoses vs. Dietary VC and Supplement VC Intake

3.3. Ranges of Optimal VC Supplement Use and Mortality Risk

3.4. Mortality Risk of Adults with and without Diabetes and with Different VC Levels

4. Discussion

4.1. Population Characteristics

4.2. Lower VC Intake Was Associated with Earlier Diagnosed Age of Type 2 Diabetes

4.3. Diabetes Is a Mortality Risk and Lower VC Intake May Elevate This Risk

4.4. VC Supplement May Be Beneficial for Diabetic People with Low Serum VC

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS)1. National Diabetes Statistics Report (USNDSR). 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Saeedi, P.; Petersohn, I.; Salpea, P.; Malanda, B.; Karuranga, S.; Unwin, N.; Colagiuri, S.; Guariguata, L.; Motala, A.A.; Ogurtsova, K.; et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 157, 107843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US National Center for Health Statistics (USCDC). Leading Causes of Death. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Ashor, A.W.; Werner, A.D.; Lara, J.; Willis, N.D.; Mathers, J.C.; Siervo, M. Effects of VC supplementation on glycaemic control: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 71, 1371–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, U.N. Vitamin C for type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Arch. Med. Res. 2019, 50, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Will, J.C.; Byers, T. Does diabetes mellitus increase the requirement for VC? Nutr. Rev. 1996, 54, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feskens, E.J.M.; Virtanen, S.M.; Rasanen, L.; Tuomilehto, J.; Stengard, J.; Pekkanen, J.; Nissinen, A.; Kromhout, D. Dietary factors determining diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance: A 20-year follow-up of the Finnish and Dutch cohorts of the Seven Countries Study. Diabetes Care 1995, 18, 1104–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, A.H.; Wareham, N.J.; Bingham, S.A.; Khaw, K.; Luben, R.; Welch, A.; Forouhi, N.G. Plasma VC level, fruit and vegetable consumption, and the risk of new-onset type 2 diabetes mellitus: The European prospective investigation of cancer—Norfolk prospective study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008, 168, 1493–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hercberg, S.; Czernichow, S.; Galan, P. Vitamin C concentration and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 634. [Google Scholar]

- Block, G.; Jensen, C.D.; Dalvi, T.B.; Norkus, E.P.; Hudes, M.; Crawford, P.B.; Holland, N.; Fung, E.B.; Schumacher, L.; Harmatz, P. VC treatment reduces elevated C-reactive protein. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009, 46, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauchla, M.; Dekker, M.J.; Rehm, C.D. Trends in vitamin C consumption in the United States: 1999–2018. Nutrients 2021, 13, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, R.S.; Leonard, S.W.; Atkinson, J.; Montine, T.J.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Bray, T.M.; Traber, M.G. Faster plasma vitamin E disappearance in smokers is normalized by VC supplementation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006, 40, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambial, S.; Dwivedi, S.; Shukla, K.K.; John, P.J.; Sharma, P. Vitamin C in disease prevention and cure: An overview. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2013, 28, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, F.E.; May, J.M. Vitamin C function in the brain: Vital role of the ascorbate transporter SVCT2. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009, 46, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.C.; Maggini, S. VC and immune function. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreadi, A.; Bellia, A.; Di Daniele, N.; Meloni, M.; Lauro, R.; Della-Morte, D.; Lauro, D. The molecular link between oxidative stress, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes: A target for new therapies against cardiovascular diseases. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2022, 62, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouakanou, L.; Xu, Y.; Peters, C.; He, J.; Wu, Y.; Yin, Z.; Kabelitz, D. Vitamin C promotes the proliferation and effector functions of human γδ T cells. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2020, 17, 462–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golding, P.H. Experimental folate deficiency in human subjects: What is the influence of vitamin C status on time taken to develop megaloblastic anaemia? BMC Hematol. 2018, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traber, M.G.; Stevens, J.F. Vitamins C and E: Beneficial effects from a mechanistic perspective. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 51, 1000–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouin, G.; Godin, J.R.; Pagé, B. The genetics of vitamin C loss in vertebrates. Curr. Genom. 2011, 12, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraki, I.; Imamura, F.; Manson, J.E.; Hu, F.B.; Willett, W.C.; van Dam, R.M.; Sun, Q. Fruit consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: Results from three prospective longitudinal cohort studies. BMJ 2013, 347, f5001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, S.A.; Keske, M.A.; Wadley, G.D. Effects of VC Supplementation on Glycemic Control and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in People with Type 2 Diabetes: A GRADE-Assessed Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, 618–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, D.J.; Spence, J.D.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Kim, Y.I.; Josse, R.G.; Vieth, R.; Sahye-Pudaruth, S.; Paquette, M.; Patel, D.; Blanco Mejia, S.; et al. Supplemental vitamins and minerals for cardiovascular disease prevention and treatment: JACC focus seminar. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US CDC. National Center for Health Statistics NHANES Comprehensive Data List. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/search/datapage.aspx (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- US CDC; National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination 364 Survey NCHS Research Ethics Review Board (ERB) Approval. 365. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/irba98.htm (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- US CDC. 2019 Public-Use Linked Mortality Files. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data-linkage/mortality-public.htm (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- US CDC. The Linkage of National Center for Health Statistics Survey Data to the National Death Index—2019 Linked Mortality File (LMF): Linkage Methodology and Analytic Considerations. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/datalinkage/2019NDI-Linkage-Methods-and-Analytic-Considerations-508.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- US CDC. NHANES 2019–2020 Procedure Manuals. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/continuousnhanes/manuals.aspx?BeginYear=2019 (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- US CDC. Defining Adult Overweight & Obesity. 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/basics/adult-defining.html (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Krinsky, N.I.; Beecher, G.R.; Burk, R.F.; Chan, A.C.; Erdman, J.J.; Jacob, R.A.; Jialal, I.; Kolonel, L.N.; Marshall, J.R.; Taylor Mayne, P.R.; et al. Dietary reference intakes for vitamin C, vitamin E, selenium, and carotenoids. Inst. Med. 2000, 19, 95–185. [Google Scholar]

- US CDC. Second National Report on Biochemical Indicators of Diet and Nutrition in the U.S. Population (2012); National Center for Environmental Health, Division of Laboratory Sciences: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2012. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/nutritionreport (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, M. Mortality in adults with and without diabetes: Is the gap widening? Clin. Epidemiol. 2017, 9, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kom, E.L.; Graubard, B.I.; Midthune, D. Time-to-event analysis of longitudinal follow-up of a survey: Choice of the time-scale. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1997, 145, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allison, P.D.; Hancock, G.R.; Mueller, R.O. Survival analysis. In the Reviewer’s Guide to Quantitative Methods in the Social Sciences; Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 413–424. [Google Scholar]

- Schober, P.; Vetter, T.R. Survival analysis and interpretation of time-to-event data: The tortoise and the hare. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 127, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. Applied Ordinal Logistic Regression Using Stata: From Single-Level to Multilevel Modeling; Sage Publications: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mosslemi, M.; Park, H.L.; McLaren, C.E.; Wong, N.D. A treatment-based algorithm for identification of diabetes type in the National health and nutrition examination survey. Cardiovasc. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, S.A.; Rasmussen, B.; van Loon, L.J.; Salmon, J.; Wadley, G.D. Ascorbic acid supplementation improves postprandial glycaemic control and blood pressure in individuals with type 2 diabetes: Findings of a randomized cross-over trial. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2019, 21, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kositsawat, J.; Freeman, V.L. VC and A1c relationship in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2006. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2011, 30, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargeant, L.A.; Wareham, N.J.; Bingham, S.; Day, N.E.; Luben, R.N.; Oakes, S.U.; Welch, A.I.; Khaw, K.T. VC and hyperglycemia in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer–Norfolk (EPIC-Norfolk) study: A population-based study. Diabetes Care 2000, 23, 726–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afkhami-Ardekani, M.; Shojaoddiny-Ardekani, A. Effect of VC on blood glucose, serum lipids & serum insulin in type 2 diabetes patients. Indian J. Med. Res. 2007, 126, 471. [Google Scholar]

- Kojo, S. Vitamin C: Basic metabolism and its function as an index of oxidative stress. Curr. Med. Chem. 2004, 11, 1041–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundy, C.; Fessler, S.N.; Johnston, C.S. Erythrocyte osmotic fragility is not linked to vitamin C nutriture in adults with well-controlled type 2 diabetes. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 954010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, K.P.; Green, S.J.; Ortiz, J.; Wu, S.C. Association between hemoglobin A1c, Vitamin C, and microbiome in diabetic foot ulcers and intact skin: A cross-sectional study. Health Sci. Rep. 2022, 5, e718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Will, J.C.; Ford, E.S.; Bowman, B.A. Serum VC concentrations and diabetes: Findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 70, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, M.A.; Chun, O.K. VC and heart health: A review based on findings from epidemiologic studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykkesfeldt, J. On the effect of vitamin C intake on human health: How to (mis) interpret the clinical evidence. Redox Biol. 2020, 34, 101532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loria, C.M.; Klag, M.J.; Caulfield, L.E.; Whelton, P.K. Vitamin C status and mortality in US adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 72, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Folsom, A.R.; Harnack, L.; Halliwell, B.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr. Does supplemental vitamin C increase cardiovascular disease risk in women with diabetes? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 80, 1194–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, A.P.; Fox, C.S.; McGuire, D.K.; Levitan, E.B.; Laclaustra, M.; Mann, D.M.; Muntner, P. Low hemoglobin A1c and risk of all-cause mortality among US adults without diabetes. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2010, 3, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Wang, D.; Coresh, J.; Selvin, E. Trends in diabetes treatment and control in US adults, 1999–2018. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 2219–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Men | College Education | Married | Smoke | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mexican | 52.0% (50.7–53.3%) | 28.4% (27.2–29.6%) | 51.9% (50.6–53.1%) | 35.1% (33.8–36.3%) |

| Hispanic | 47.0% (45.2–48.8%) | 44.6% (42.8–46.5%) | 46.6% (44.8–48.4%) | 35.6% (33.9–37.4%) |

| White | 48.6% (47.8–49.4%) | 62.5% (61.8–63.3%) | 58.1% (57.3–58.9%) | 48.1% (47.3–48.9%) |

| African | 44.6% (43.6–45.6%) | 49.0% (47.9–50.0%) | 32.2% (31.2–33.1%) | 38.8% (37.8–39.8%) |

| Others | 48.2% (46.3–50.2%) | 66.7% (64.8–68.5%) | 56.4% (54.4–58.3%) | 35.8% (33.8–37.8%) |

| mean | 48.3% (47.7–48.9%) | 57.5% (56.9–58.0%) | 53.9% (53.3–54.5%) | 44.5% (43.9–45.0%) |

| 1 Diet VC below EAR | Taking VC supply. | With A1c measured | With fasting glucose measured | |

| Mexican | 45.0% (43.8–46.3%) | 22.3% (21.3–23.4%) | 97.0% (96.6–97.4%) | 46.9% (45.6–48.2%) |

| Hispanic | 44.4% (42.5–46.2%) | 26.8% (25.2–28.5%) | 96.5% (95.8–97.1%) | 46.9% (45.1–48.7%) |

| White | 40.9% (40.1–41.7%) | 41.4% (40.6–42.1%) | 97.1% (96.9–97.4%) | 47.3% (46.5–48.1%) |

| African | 46.2% (45.2–47.2%) | 25.2% (24.3–26.1%) | 92.7% (92.1–93.2%) | 44.8% (43.8–45.8%) |

| Others | 41.7% (39.7–43.7%) | 36.2% (34.3–38.1%) | 95.3% (94.5–96.1%) | 46.2% (44.2–48.2%) |

| mean | 42.1% (41.5–42.7%) | 36.8% (36.2–37.4%) | 96.5% (96.3–96.7%) | 46.9% (46.3–47.5%) |

| 2 Serum VC < 0.2 | With type 1 diabetes | With type 2 diabetes | Deceased | |

| Mexican | 4.0% (3.1–5.1%) | 0.3% (0.2–0.5%) | 11.8% (11.1–12.6%) | 4.4% (4.0–4.8%) |

| Hispanic | 2.7% (1.6–4.3%) | 0.5% (0.3–0.7%) | 11.1% (10.1–12.3%) | 5.1% (4.4–5.9%) |

| White | 7.8% (7.1–8.6%) | 0.6% (0.5–0.7%) | 8.9% (8.5–9.4%) | 11.1% (10.8–11.5%) |

| African | 5.6% (4.8–6.5%) | 0.9% (0.7–1.1%) | 14.2% (13.5–14.9%) | 9.7% (9.2–10.3%) |

| Others | 5.1% (3.8–6.9%) | 0.3% (0.2–0.6%) | 12.2% (11.0–13.5%) | 5.5% (4.7–6.4%) |

| mean | 6.8% (6.2–7.3%) | 0.6% (0.5–0.6%) | 10.1% (9.8–10.4%) | 9.7% (9.4–10.0%) |

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | L95% | U95% | Mean | L95% | U95% | |

| dietary VC (no-supplement) intake (mg/day) | ||||||

| No-diabetes | 91.6 | 89.7 | 93.5 | 78.1 | 76.7 | 79.5 |

| Type 1 | 85.1 | 68.6 | 101.5 | 83.2 | 67.9 | 98.5 |

| Type II | 80.7 | 76.1 | 85.3 | 70.2 | 66.9 | 73.5 |

| supplementary VC intake (mg/day) | ||||||

| No-diabetes | 83.1 | 77.9 | 88.3 | 94.6 | 89.0 | 100.2 |

| Type 1 | 100.8 | 42.7 | 159.0 | 75.8 | 44.8 | 106.8 |

| Type II | 97.9 | 78.3 | 117.6 | 90.8 | 76.9 | 104.7 |

| serum VC level (mg/dL) | ||||||

| No-diabetes | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.04 |

| Type 1 | 0.87 | 0.74 | 1.01 | 0.96 | 0.82 | 1.10 |

| Type II | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.92 |

| fasting plasma glucose (mg/dL) | ||||||

| No-diabetes | 100.4 | 100.1 | 100.8 | 96.4 | 96.1 | 96.7 |

| Type 1 | 220.2 | 189.1 | 251.3 | 193.5 | 166.5 | 220.5 |

| Type II | 164.4 | 160.0 | 168.7 | 152.1 | 148.4 | 155.9 |

| Glycohemoglobin A1c (%) | ||||||

| No-diabetes | 5.4 | 5.3 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 5.3 | 5.4 |

| Type 1 | 8.5 | 8.0 | 9.0 | 7.9 | 7.5 | 8.4 |

| Type II | 7.5 | 7.4 | 7.6 | 7.3 | 7.2 | 7.4 |

| BMI Range | Diet. VC (mg/Day) | SerVC (mg/dL) | Fasting Glucose (mg/dL) | A1c (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underweight | <18.5 | 87.3 (70.7–103) | 0.93 (0.81–1.05) | 93.7 (90.6–96) | 5.2 (5.1–5) |

| Normal weight | 18.5–24.9 | 86.8 (83.1–90) | 0.98 (0.95–1) | 97.7 (96.3–99) | 5.3 (5.2–5) |

| Pre-obesity | 25.0–29.9 | 86.3 (82.9–89) | 0.93 (0.9–0.95) | 103.9 (102.5–105) | 5.4 (5.4–5) |

| Obesity class I | 30.0–34.9 | 77.5 (73.2–81) | 0.83 (0.8–0.86) | 108.8 (106.7–110) | 5.6 (5.6–5) |

| Obesity class II | 35.0–39.9 | 72.9 (66.8–79) | 0.75 (0.71–0.8) | 113.4 (110.3–116) | 5.8 (5.7–5) |

| Obesity class III | ≥40 | 76.5 (68.6–84.4) | 0.72 (0.66–0.77) | 118.4 (114.6–122.2) | 5.9 (5.8–6.1) |

| 1 Correlations with diet VC | 1 | 0.93 * | −0.89 * | −0.89 * | |

| Correlations with serum VC | 1 | −0.94 * | −0.96 * | ||

| 1 Odds Ratio | L95% | U95% | |

|---|---|---|---|

| With adequate VC intake vs. VC intake below EAR and with no VC supplement vs. with VC supplement | |||

| VC intake below EAR | 1.20 | 1.10 | 1.30 |

| with no VC supplement | 1.28 | 1.18 | 1.40 |

| With ranges of VC supplement vs. no VC supplement | |||

| 0–499.9 mg/day | 0.78 | 0.71 | 0.86 |

| 500–999.9 mg/day | 0.79 | 0.66 | 0.96 |

| 1000–1999.9 mg/day | 0.64 | 0.49 | 0.85 |

| ≥2000 mg/day | 1.32 | 0.68 | 2.56 |

| Ages (years) of type 2 diabetes diagnoses of US adults vs. their total VC and VC supplement intake | |||

| Percentile | 25th | 50th | 75th |

| with adequate VC intake | 38 | 50 | 60 |

| with VC intake below EAR | 37 | 49 | 60 |

| with suppl VC | 40 | 51 | 60 |

| without suppl VC | 36 | 49 | 60 |

| Low Total VC and No VC Supplement with Adequate VC Intake and VC Supplement as References 1 | Low and Deficient Serum VC with Normal Serum VC as Reference 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VC intake | Haz. Ratio | L95% | U95% | Serum VC | Haz. Ratio | L95% | U95% |

| Non-diabetes | Non-diabetes | ||||||

| VC intake below EAR | 1.28 | 1.18 | 1.38 | low serum VC | 1.55 | 1.21 | 1.98 |

| with no VC suppl | 1.24 | 1.15 | 1.34 | VC deficient | 2.19 | 1.73 | 2.76 |

| Type 1 diabetes | Type 1 diabetes | ||||||

| VC intake below EAR | 0.97 | 0.65 | 1.45 | low serum VC | 1.27 | 0.50 | 3.20 |

| with no VC suppl | 1.25 | 0.86 | 1.81 | VC deficient | 2.78 | 0.80 | 9.73 |

| Type 2 diabetes | Type 2 diabetes | ||||||

| low VC intake | 1.11 | 0.95 | 1.29 | low serum VC | 1.61 | 1.17 | 2.20 |

| very low VC intake | 1.25 | 1.05 | 1.49 | VC deficient | 1.84 | 1.10 | 3.08 |

| with no VC suppl | 1.20 | 1.05 | 1.38 | ||||

| 25th | 50th | 75th | Differences of the 50th Percentile Survival Years of Varied VC with Normal VC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival years of non-diabetes vs. serum VC | ||||

| 1 Normal S. VC | 83.1 | 88.7 | 92.7 | 0.0 |

| Low S. VC | 79.3 | 85.0 | 90.8 | 3.7 |

| VC deficient | 72.7 | 83.3 | 88.3 | 5.3 |

| Survival years of type 1 diabetes vs. serum VC | ||||

| Normal S. VC | 70.1 | 81.8 | 87.6 | 0.0 |

| Low S. VC | 62.3 | 77.2 | 83.6 | 4.7 |

| VC deficient | 64.8 | 66.7 | 66.7 | 15.2 |

| Survival years of type 2 diabetes vs. serum VC | ||||

| Normal S. VC | 80.7 | 86.2 | 90.3 | 0.0 |

| Low S. VC | 73.8 | 82.6 | 86.8 | 3.6 |

| (1) | 81.2 | 88.3 | 5.0 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, H.; Karp, J.; Sun, K.M.; Weaver, C.M. Decreasing Vitamin C Intake, Low Serum Vitamin C Level and Risk for US Adults with Diabetes. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3902. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14193902

Sun H, Karp J, Sun KM, Weaver CM. Decreasing Vitamin C Intake, Low Serum Vitamin C Level and Risk for US Adults with Diabetes. Nutrients. 2022; 14(19):3902. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14193902

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Hongbing, Jonathan Karp, Kevin M. Sun, and Connie M. Weaver. 2022. "Decreasing Vitamin C Intake, Low Serum Vitamin C Level and Risk for US Adults with Diabetes" Nutrients 14, no. 19: 3902. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14193902

APA StyleSun, H., Karp, J., Sun, K. M., & Weaver, C. M. (2022). Decreasing Vitamin C Intake, Low Serum Vitamin C Level and Risk for US Adults with Diabetes. Nutrients, 14(19), 3902. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14193902