Sociocultural Influences Contribute to Overeating and Unhealthy Eating: Creating and Maintaining an Obesogenic Social Environment in Indigenous Communities in Urban Fiji

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Approval

3. Results

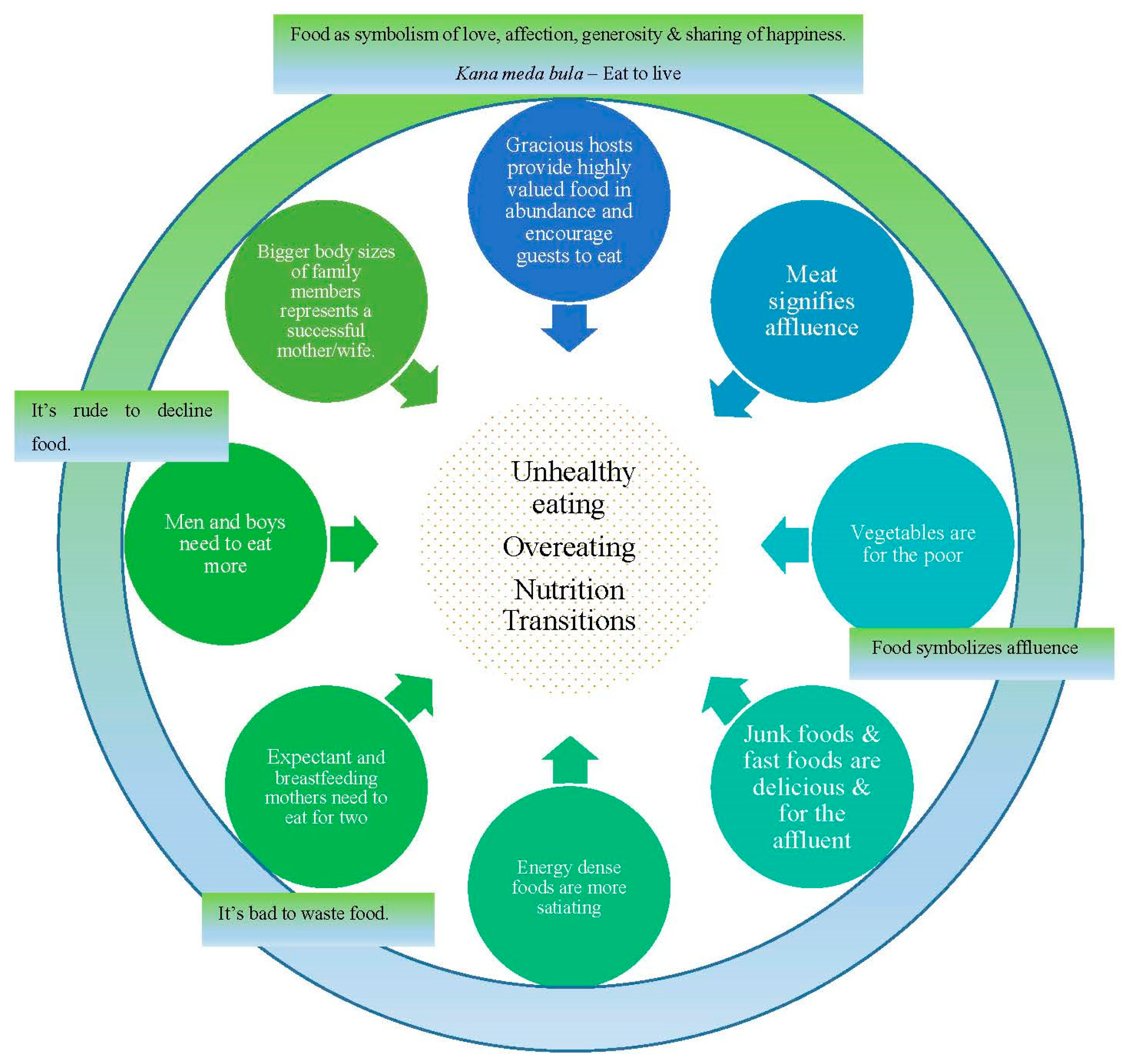

3.1. Cultural Norms, Expectations and Pressures That Create and Maintain a Social Environment of Overeating and Unhealthy Eating

3.1.1. Generous Hosts Provide Highly-Valued Food in Abundance and Encourage Guests to Eat

Mel: Kana meda bula! The more you eat, the more you live, in fact the better you live [Laughs]. You leave your, what you say, your diet, or worries about health and enjoy the vibe, the environment and the company [laughs]. Basically, enjoy now and worry about those things later. And so, you get tempted, I mean, who wouldn’t? We love our food and it’s our traditional food and it’s not bad food. So, eat today and I will detox tomorrow [Laughs].

Mel: As my mother-in-law would say “It’s better for us to have leftovers than to have that pot dry and people can tell that there was less food. If there is still leftovers, then you know your guests ate well and you know, it was a successful function”. And so, we keep refilling the bowls on the serving table and we encourage our guests to eat well. It looks bad if a serving bowl is empty or if run out of food. So, when you cook or cater, you always make sure there’s leftovers.

Maggie: I think that’s just in our culture, the way we meet people during these gatherings, the happiness we feel and one of the way we show love is to offer food.

Leba: Oh, definitely when we have occasions like wedding or something like get-together, cousin said … or family will go [say], “Kana kana, c’mon c’mon, we only live once! Kana meda bula. It’s been a long [sic] when we meet again come on, this is the only time that we eat!”.

Api: Because when we go to a gathering, the food is in abundance so from my point of view, people just gorge themselves. [] And when people dish a little bit, others will keep encouraging, “c’mon c’mon, there’s more, there’s more. Have some more! There’s plenty of food for everybody, kana meda bula” So you are opening that door for people to overeat. [] Also, in parties or social gatherings, you find that people keep nudging each other, sort of encouraging each other to eat more. Like “mai kana, mai kana”. And it seems to be a cultural thing too. Like part of iTaukei hospitality is to encourage your visitors to eat more. It’s a Pacific culture.

Ester: To be honest, I hosted my son’s first birthday and I had to take loan for it and it took me three years to pay it back! Like these affairs are expensive! We had to invite several families. We have to cater for everyone who attends and also for their takeaways for people who didn’t!

Kesa: Like we end up cooking more meat than usual during family visits. This may mean that we don’t have enough for the rest of the week or till the next shopping. But yes, we try to do our best to meet that expectation.

Sala: Yes, like you know how we alternate between veggies and meat or fish every day? And we enjoy simple meals, generally boiled leafy greens? All that goes out the window when we have people over [laughs]. You have to make something special and maybe a few types of dishes with meat and generally more rich food like add lolo (coconut cream) to the dishes. Like if we have a lovo, it’s a lot of meat, a lot of coconut cream. So, the meal does become very unhealthy. In fact, the meal becomes exactly what I discourage at home.

3.1.2. Pressures Experienced by the Individual(s) Being Offered the Food

It’s Rude to Decline Food

Ester: Also for us, in our culture, if anyone offers food, it’s kind of disrespectful to decline. Like it’s a bit rude and times you feel that when you decline you are giving the message that the food isn’t good either. So, it both sides [sic] and ends with people eating way more than they should.

Maggie: And if you are going in [a social gathering], there is a pressure that you cannot refuse something that they offer, like it’s disrespectful to do so. So much time, money, and effort is spent on preparing these feasts and it’s rude to then decline the food. And they are your family. It’s very difficult at times. Because you don’t want to appear that you are some high shot who is on a particular diet.

Leba: And then there comes someone saying, “You know your grandmother cooked that, you know, she put a lot of effort!” And then you feel obligated to have more, it’s like emotional blackmail.

Sala: I will still take a bit out of respect for the host so that they don’t feel offended and they are satisfied that I am enjoying the food they have prepared for us.

It’s Bad to Waste Food

Maggie: But then because I was really wanting to eat more, I mean I love subways, I went ahead and bought another one and after a few bites, I was full but because of the money that was spent, I don’t want to waste it, so I ate all of it. [laughs]

Leba: So, I encourage my children to finish their food because we work really hard to, you know, to put the meals on the table. And it almost feels sinful to waste it you know… when there are so many kids, kids starving in the world. Mostly when we get, get together in church in our Fijian [iTaukei] occasions where my children, you know, and they cannot finish their food and they bring it over to me, so I just don’t … I make use of it, like finish it. I have to be the mother and finish their food so it’s not wasted.

Tevi: But I always take out food for my parents and put it aside before the rest of us eat. And no one else can eat that food. [] If they leave food, then it gets wasted. We can’t eat that food, so they never waste it. They finish all of it.

3.1.3. Gender-Specific Norms

Men and Boys Need to Eat More Because They Engage in Hard Labor

Luisa: Men eat more than women because they do much of the hard work …, like work on the farm, harvesting, getting firewood. So, he eats more than any of us. And we have to make sure he eats well so that he can do all the hard work.

Kala: Men are generally encouraged to eat more, because men are heads of family, they sort of take the top place and they are expected to do hard work.

Mere: Oh yeah Shaz, like when we have my mother-in-law around, that’s what she does. “Kana levu… Kana kana” Like telling my husband and my son to eat more, more, more. Like you know in iTaukei, everyone eats like mountains. [Laughs]. Like for me, whatever, I take out. I know it’s enough for them.

Kesa: Yes. Yes, very much, even at home, in our family, my mother just makes sure of that, you know, my husband is offered food first at the table or if he comes home late, “Make sure his food is set aside, specifically for him.” If he goes outside for gardening, she would tell “Offer him some cassava, some tea.” So, culture still very much prevalent that way [Laughs].

Rusila: Yes, I remember when, when I got pregnant, in my early months of pregnancy I was still skinny, and oh my elders were telling me you’re not healthy the baby is suffering, you need to eat a lot, and I’m thinking, “What? What does that have to do with the baby?” [Laughs] I guess there’s some traditional and cultural tags to how much a male or female should eat, also if you are a breastfeeding mother, or a pregnant woman you are expected to eat a lot, compared to just a young teenager, they won’t expect you to eat a lot. [] I when I was pregnant with my daughter. They like, “Eat, eat, eat!” and then when I was breastfeeding, “Eat, eat, eat!” and after I had my daughter and I weaned off my daughter, they started “Stop eating, stop eating, stop eating!”

Bigger Body Sizes of Family Members Represent a Successful Mother or Wife

Kesa: And you know also, after marriage, my husband gained so much weight, and his family look at it as … that, that I am looking after him really well. That I am a good wife, and that used to make me feel good about myself. But we now know that it’s not healthy for him to be like that.

Faith: By looking at your family members, like they’re healthy and the way they grow, not skinny and all. So, so you’ve got a skinny kid, they think that you’re not doing so well as a mother. [] Um, they’ll say bad things about that mother. They’ll say, “she just go partying on, going here going there without taking care of the kids”. Like not giving them the right food, just giving them junk food. They always judge like that.

Ester: Yes, definitely. Oh, I get this a lot! Sometimes when you go to a function, people will be commenting “Hey, saying my son’s name, you so skinny! Your mum feeding you well?” It always makes me think, “Whether I am feeding my kids well? Whether I am a good mum?” I mean, I know they are not underweight. They are healthy weight, but you still get those comments. Especially before when I was 105 kgs, I would get comments like “Oh we know where all the food is going! It’s all going to mummy, mummy’s eating your share too” It used to really really affect me, I used to feel really down. But now I know that they are eating healthy and that matters more than them being chubby! [] Well for men, if someone says that my husband has lost weight, then there’s that hint or suggestion that I am not looking after my husband properly or that he is sick. So, in my experience, it’s the opposite for men. Gosh, there are so many mixed messages!

3.2. Misplaced Valuing of Foods that Cause Nutrition Transition and Unhealthy Eating

3.2.1. Meat Is for the Rich and Vegetables Are for the Poor

Kala: I think, from experience, if you go to a Fijian function or event and there’s no meat or not enough meat, people will talk about it. It’s just culture, it’s always how it’s been. And people look forward to a function for the food that’s going to be there, especially the pork, the beef, the chicken that’s going to be there. Our events revolve around our food and the meat is the main attraction.

Ester: So, if my family is eating healthy, like we are including more vegetables in our diet. I’m going to put salad on the table, include veggies in the soup but in these communal functions, we’ll see a big pig on the main table. And when people enter, that just shows how wealthy the host family is. But putting salads, adding veggies, it shows “Oh so this is how much they have in their bank account!” [Laughs]. Meat represents how wealthy a person is in iTaukei culture.

Kesa: Society does have an impact on the family and they are always judging, how the family is, what they eat, how they look, you know. [] And so, when they come, when they come home, they look at you know what’s being served. They look at the level of income and the level of, you know, what my husband and I are willing to do for whoever’s coming home, or the meal itself, you know, so I think sometimes the food that you eat defines the status of your life, I would say, your class. And that really affects the family, like trying to maintain that image. We have to try to serve meat when people visit because they will talk if we don’t.

Sala: I want to share an incident. So, one of my nieces went to stay with a family for a few days and this family is of SDA [Seventh Day Adventist] faith, so you know they hardly eat meat. Anyways, when she came back, she told her parents that “We should help that family because they are very poor, they don’t get meat to eat. We should buy groceries for them”. You know what I mean, we need to change that mindset. That vegetables are for poor people only. For me, when I heard that, I realized that not only adults, but children also feel that, and it is so ingrained in our culture that meat is for the wealthy and vegetables are for poor people.

Maggie: Ok, so sausages and tuna or egg sandwiches are easier lunches to prepare, but for me, the main thing is that … to be honest, I am a bit miser when it comes to buying chicken. When I do shopping, I hardly buy the chicken because, for me, like you buy one chicken and you cook it one day and it finishes but you can by 4–5 cans of tuna with the same money and it will last you a few meals. So, it’s really the price. I always opt for tuna, tinned fish, or sausages because you can spread it to a few meals.

Mel: I will do tinned fish and tuna, and corned mutton and, especially, sausages because we can’t afford fresh beef and pork.

3.2.2. Energy Dense Foods Are More Satiating

Kesa: And for my husband, on the days he has to go out of Suva, I make sure he eats his dinner well, like I might boil extra cassava or dalo [root crops] so that he has heavy dinner and that’s a heavy food. And at times the leftover cassava, he will have it for breakfast. And that keeps him going till lunch.

Mel: The cassava, it’s heavy, even if you eat a little bit of curry and whole of cassava, it will take you through the night.

3.2.3. A Palate for Junk Food and Fast Foods

Sala: They like cream biscuits like Tymo, and the normal Twisties, Bongo, Doritos and we buy it during grocery shopping. They study late and they keep snacking on this, like when they are under stress and have assignments due.

Mere: My kids love the blue packet Twisties [extra-cheese-flavored snack] and whenever we have extra [money] so then we buy some when grocery shopping or they go and buy from the shops around here.

Kesa: Because his work, they normally move around, Suva, Navua and Nausori so fast, fast food, yeah, fish and chips along the way … [] And for me, I have, the famous Southern Cross [fast food place on campus] fish and chips for lunch.

Sala: On shopping days we get fish and chips for the girls, they enjoy it. Or when we go out as a family for dinner, maybe twice a month.

Ru: So, you can imagine when I come home after that meeting [stressful day at work]. Oh man, if, if, if I have a lot of energy, maybe I could go, come with my stuff in the taxi, drive-through McDonald’s and just have only spicy chicken and sprite. I need those

Mel: When running late from work, I can’t cook, then we opt for fast food and takeaways. But especially on birthdays, anniversary, so when we are celebrating, then we try to do something special and save up so that we can eat Mc Donald’s or go out for pizza. [] I think it’s taste of the food, but also the atmosphere is also nice and that’s why you want to go somewhere special and enjoy your special occasion.

Mel: So, it’s only when we can afford it. I think people only eat out when they can afford it so they have the money, they are rich, they can afford to go out for burgers and chicken and chips, pizza and all those kinds of food … One of my close friends is always taking her kids to fast food places and posting pictures, and I’m thinking “Man she has the money for it!”

4. Discussion

4.1. Public Health Implications

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Bentham, J.; Di Cesare, M.; Bilano, V.; Bixby, H.; Zhou, B.; Stevens, G.A. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2017, 390, 2627–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Global Obesity Observatory. Ranking (% Obesity by Country). Available online: https://data.worldobesity.org/rankings/ (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases Country Profiles 2018; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; 223p, Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274512 (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Chand, S.S.; Singh, B.; Kumar, S. The economic burden of non-communicable disease mortality in the South Pacific: Evidence from Fiji. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buksh, S.M.; Hay, P.; de Wit, J.B.F. Urban Fijian Indigenous Families’ Positive and Negative Diet, Eating and Food Purchasing Experiences During the COVID 19 Safety Protocols. JPAC 2021, 41, 31–53. [Google Scholar]

- Manent, J.I.R.; Jané, B.A.; Cortés, P.S.; Busquets-Cortés, C.; Bote, S.A.; Comas, L.M.; González, Á.A.L. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on anthropometric variables, blood pressure, and glucose and lipid profile in healthy adults: A before and after pandemic lockdown longitudinal study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buscemi, S.; Buscemi, C.; Batsis, J.A. There is a relationship between obesity and coronavirus disease 2019 but more information is needed. Obesity 2020, 28, 1371–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M.; Du, S.; Green, W.D.; Beck, M.A.; Algaith, T.; Herbst, C.H.; Shekar, M. Individuals with obesity and COVID-19: A global perspective on the epidemiology and biological relationships. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e13128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, A.; Feng, W.; Asal, V. What is driving global obesity trends? Globalization or “modernization”? Glob. Health 2019, 15, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thow, A.M.; Snowdon, W. The effect of trade and trade policy on diet and health in the Pacific Islands. Trade Food Diet Health Perspect. Policy Options 2010, 147, 168. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, R.G.; Lawrence, M. Globalisation, food and health in Pacific Island countries. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 14, 298–305. [Google Scholar]

- Ofa, S.V.; Gani, A. Trade policy and health implication for pacific island countries. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2017, 44, 816–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, E.; Fang, P. Papua New Guinea agri-food trade and household consumption trends point towards dietary change and increased overweight and obesity prevalence. Glob. Health 2021, 17, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievert, K.; Lawrence, M.; Naika, A.; Baker, P. Processed foods and nutrition transition in the Pacific: Regional trends, patterns and food system drivers. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ravuvu, A.; Lui, J.P.; Bani, A.; Tavoa, A.W.; Vuti, R.; Win Tin, S.T. Analysing the impact of trade agreements on national food environments: The case of Vanuatu. Glob. Health 2021, 17, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thow, A.M.; Heywood, P.; Schultz, J.; Quested, C.; Jan, S.; Colagiuri, S. Trade and the nutrition transition: Strengthening policy for health in the Pacific. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2011, 50, 18–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snowdon, W.; Thow, A.M. Trade policy and obesity prevention: Challenges and innovation in the Pacific Islands. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Veatupu, L.; Puloka, V.; Smith, M.; McKerchar, C.; Signal, L. Me’akai in Tonga: Exploring the nature and context of the food Tongan children eat in ha’apai using wearable cameras. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2019, 16, 1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guell, C.; Brown, C.R.; Iese, V.; Navunicagi, O.; Wairiu, M.; Unwin, N. “We used to get food from the garden.” Understanding changing practices of local food production and consumption in small island states. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 284, 114214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, E.; Bhagtani, D.; Iese, V.; Brown, C.R.; Fesaitu, J.; Hambleton, I.; Unwin, N. Food sources and dietary quality in small island developing states: Development of methods and policy relevant novel survey data from the Pacific and Caribbean. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teevale, T.; Scragg, R.; Faeamani, G.; Utter, J. Pacific parents’ rationale for purchased school lunches and implications for obesity prevention. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 21, 282–290. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K.N.; Sendall, M.C.; Gurung, A.; Carne, P. Understanding socio-cultural influences on food intake in relation to overweight and obesity in a rural indigenous community of Fiji islands. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2021, 32, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seubsman, S.A.; Kelly, M.; Yuthapornpinit, P.; Sleigh, A. Cultural resistance to fast-food consumption? A study of youth in north eastern Thailand. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ministry of Health and Medical Sciences. Fiji NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report 2011. Available online: https://www.health.gov.fj/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Fiji-STEPS-Report-2011.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Johns, C.; Lyon, P.; Stringer, R.; Umberger, W. Changing urban consumer behaviour and the role of different retail outlets in the food industry of Fiji. APDJ 2017, 24, 117–145. Available online: https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/chap%205_1.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- United Nations Human Settlements Programme. Fiji: Greater Suva Urban Profile. 2012. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/documents/2019-06/fiji_greater_suva_urban_profile.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- McCabe, M.P.; Mavoa, H.; Ricciardelli, L.A.; Schultz, J.T.; Waqa, G.; Fotu, K.F. Socio-cultural agents and their impact on body image and body change strategies among adolescents in Fiji, Tonga, Tongans in New Zealand and Australia. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2008, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fiji Bureau of Statistics. Population by Religion–2007 Census of Population. 2022. Available online: https://www.statsfiji.gov.fj/statistics/social-statistics/religion.html (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2021, 13, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, S.L.; Horton, B.; Zhang, S. Communicating love: Comparisons between American and east Asian university students. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2008, 32, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.C.; Dahl, Z.T.; Weyant, R.J.; McNeil, D.W.; Foxman, B.; Marazita, M.L.; Burgette, J.M. Exploring mothers’ perspectives about why grandparents in Appalachia give their grandchildren cariogenic foods and beverages: A qualitative study. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2022, in press. [CrossRef]

- Gregersen, S.C.; Gillath, O. How food brings us together: The ties between attachment and food behaviors. Appetite 2020, 151, 104654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamburg, M.E.; Finkenauer, C.; Schuengel, C. Food for love: The role of food offering in empathic emotion regulation. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Donohoe, S.; Gram, M.; Marchant, C.; Schänzel, H.; Kastarinen, A. Healthy and indulgent food consumption practices within Grandparent–Grandchild identity bundles: A qualitative study of New Zealand and Danish families. J. Fam. Issues 2021, 42, 2835–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheen, F.; Hardman, C.A.; Robinson, E. Food waste concerns, eating behaviour and body weight. Appetite 2020, 151, 104692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, E.; Hardman, C.A. Empty plates and larger waists: A cross-sectional study of factors associated with plate clearing habits and body weight. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 750–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, E.; Aveyard, P.; Jebb, S.A. Is plate clearing a risk factor for obesity? A cross-sectional study of self-reported data in US adults. Obesity 2015, 23, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- World Obesity. Report Card: Fiji. Available online: https://data.worldobesity.org/country/fiji-69/report-card.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Orio, F.; Tafuri, D.; Ascione, A.; Marciano, F.; Savastano, S.; Colarieti, G.; Muscogiuri, G. Lifestyle changes in the management of adulthood and childhood obesity. Minerva Endocrinol. 2016, 41, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Simmonds, M.; Burch, J.; Llewellyn, A.; Griffiths, C.; Yang, H.; Owen, C.; Woolacott, N. The use of measures of obesity in childhood for predicting obesity and the development of obesity-related diseases in adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Technol. Assess. 2015, 19, 1–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khan, N.; Cigljarevic, M.; Schultz, J.T.; Dyer, E. Evidence for a curriculum review for secondary schools in Fiji. PHD 2006, 13, 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Clonan, A.; Roberts, K.E.; Holdsworth, M. Socioeconomic and demographic drivers of red and processed meat consumption: Implications for health and environmental sustainability. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2016, 75, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qian, F.; Riddle, M.C.; Wylie-Rosett, J.; Hu, F.B. Red and processed meats and health risks: How strong is the evidence? Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Varraso, R.; Dumas, O.; Boggs, K.M.; Willett, W.C.; Speizer, F.E.; Camargo, C.A., Jr. Processed meat intake and risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among middle-aged women. EClinicalMedicine 2019, 14, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buksh, S.M.; de Wit, J.B.F.; Hay, P. Sociocultural Influences Contribute to Overeating and Unhealthy Eating: Creating and Maintaining an Obesogenic Social Environment in Indigenous Communities in Urban Fiji. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2803. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14142803

Buksh SM, de Wit JBF, Hay P. Sociocultural Influences Contribute to Overeating and Unhealthy Eating: Creating and Maintaining an Obesogenic Social Environment in Indigenous Communities in Urban Fiji. Nutrients. 2022; 14(14):2803. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14142803

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuksh, Shazna M., John B. F. de Wit, and Phillipa Hay. 2022. "Sociocultural Influences Contribute to Overeating and Unhealthy Eating: Creating and Maintaining an Obesogenic Social Environment in Indigenous Communities in Urban Fiji" Nutrients 14, no. 14: 2803. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14142803

APA StyleBuksh, S. M., de Wit, J. B. F., & Hay, P. (2022). Sociocultural Influences Contribute to Overeating and Unhealthy Eating: Creating and Maintaining an Obesogenic Social Environment in Indigenous Communities in Urban Fiji. Nutrients, 14(14), 2803. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14142803