Abstract

Despite growing awareness of the financial burden that a cancer diagnosis places on a household, there is limited understanding of the risk for food insecurity among this population. The current study reviewed literature focusing on the relationship between food insecurity, cancer, and related factors among cancer survivors and their caregivers. In total, 49 articles (across 45 studies) were reviewed and spanned topic areas: patient navigation/social worker role, caregiver role, psychosocial impacts, and food insecurity/financial toxicity. Patient navigation yielded positive impacts including perceptions of better quality of care and improved health related quality of life. Caregivers served multiple roles: managing medications, emotional support, and medical advocacy. Subsequently, caregivers experience financial burden with loss of employment and work productivity. Negative psychosocial impacts experienced by cancer survivors included: cognitive impairment, financial constraints, and lack of coping skills. Financial strain experienced by cancer survivors was reported to influence ratings of physical/mental health and symptom burden. These results highlight that fields of food insecurity, obesity, and cancer control have typically grappled with these issues in isolation and have not robustly studied these factors in conjunction. There is an urgent need for well-designed studies with appropriate methods to establish key determinants of food insecurity among cancer survivors with multidisciplinary collaborators.

1. Introduction

Despite overall declining incidence rates in men and stable rates in women, the number of cancer survivors continues to grow in the United States (US), underscoring the importance of addressing health related quality of life (HRQOL) and food insecurity in this population [1]. Food insecurity is defined as the lack of consistent access to nutritionally adequate and safe food acquired in socially acceptable ways [2]. The impact of food insecurity is essential for considering among cancer survivors that experience a financial burden coupled with potential immunosuppression and need for adequate nutrition [3,4]. However, there has been very little integration of research focusing on food insecurity among low-income cancer survivors and the relationship to related psychosocial outcomes.

Individuals with lower socioeconomic status carry a greater proportion of the burden of obesity and cancer incidence and mortality [5,6,7,8]. These disparities indicate inequalities in cancer screening, dietary patterns, physical activity, and other health behaviors [7]. Broadly across the literature, emphasis in research among low-income populations and cancer has typically been placed on best practices for cancer screening and treatment [9,10,11]. Existing reviews across a general population of cancer survivors with some emphasis on low-income populations have addressed factors related to employment [12,13,14], self-management and psychosocial interventions [15], and financially burdened family caregivers [16]. Consequently, there remains sparse evidence regarding the role of diet and food insecurity in cancer prevention and control but there is literature more specific to cancer survivors. The purpose of this scoping literature review is to examine the relationship between food insecurity, cancer, and related factors among cancer survivors and their caregivers to inform programmatic and policy efforts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

A search of three bibliographic databases was conducted in November of 2018 (Pubmed, EBSCO/CINAHL, and PsychINFO). The search was limited to studies in English published since 1980 that were specific to the US and other English-speaking high-income countries. Searches were conducted using medical subject headings and synonyms for food insecurity and cancer and English-speaking high-income countries. A final step was to conduct a hand search of reference lists for additional relevant titles and Google Scholar to ensure that all relevant literature was included.

2.2. Study Selection

All identified citations were uploaded to DistillerSR (tool that facilitates reviews with greater transparency and audit-ready results; Evidence Partners, Ottawa, ON, Canada). Processes that followed were completed in DistillerSR and include title-, abstract-, and full-text level screening, and data extraction. Exclusion criteria during title and abstract screening stages included manuscripts that were literature reviews/metanalyses, letters to the editor, commentaries, studies conducted in a non-English-speaking country, and titles that were conference proceedings.

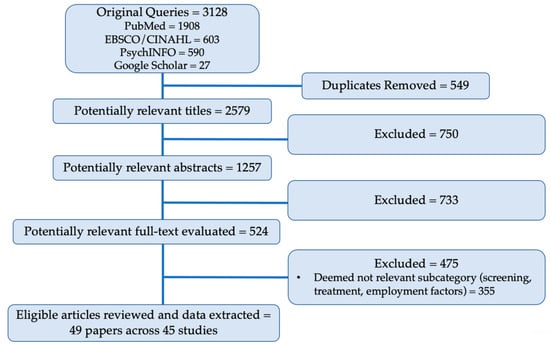

Specific sub-topics were retained that were most relevant for the current literature review based upon a lack of existing reviews, which included, food insecurity or financial impacts of cancer; the role of caregivers; patient navigation. During full-text data extraction, it was determined that certain sub-topics were outside of the scope of this review or have several existing reviews published [12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. The topics that were excluded at this stage included: the impact of poverty on cancer, disparities in cancer treatment, cancer screening among underserved populations, and work/employment factors (applied to 355 articles). An additional 120 articles were excluded at the full-text data extraction phase due to earlier stage exclusion criteria that were not detected, yielding a final 49 articles across 45 studies summarized in this review. Figure 1 shows the process for study selection and review and the number of papers that were excluded at each stage.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of inclusion for this review of food insecurity and related factors among cancer survivors. Pubmed, EBSCO/CINAHL, PsychINFO and Google Scholar are bibliographic databases.

2.3. Data Extraction

Title and abstract screening were performed for each article by one of four authors (C.P., L.C., W.C., T.G.), after several rounds of consensus building, full-text screening on the remaining titles was performed by two independent reviewers (combination of: C.P., L.C., W.C., T.G.) to determine inclusion or exclusion from the literature review with conflicts resolved between these four authors. The full-text data extraction in DistillerSR including fields: country, purpose, measurement tools, location (geography, institutions, rural/urban), design, study population, summary of results, implications.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

The initial search yielded 3128 references that were added to DistillerSR software from PubMed (n = 1908), EBSCO/CINAHL (n = 603), PsychINFO (n = 590), and Google Scholar (n = 27). An integrated duplication detection tool was used to identify redundant citations. Duplicates were removed (n = 549), leaving 2759 titles to screen for further exclusion criteria. Following an initial title screen, 1257 references advanced to the abstract screen. In the abstract screening phase, the full abstracts were reviewed for further detection of exclusion criteria, which resulted in 524 of the titles being retained. At the full-text data extraction stage, 355 articles were excluded because their topic areas were deemed outside of the scope of the current review (employment and return to work, n = 87; cancer screening and prevention, n = 184; cancer treatment disparities, n = 48; impact of poverty, n = 25; other, n = 11).

3.2. Study Characteristics

The 49 articles across 45 studies selected for inclusion spanned three different main topic areas: patient navigation (PN) and social worker role (n = 12); caregiver role and impact (n = 9); psychosocial impacts of cancer (n = 16); food insecurity and financial toxicity (n = 12). These 45 studies spanned countries where the studies took place included: Australia (n = 2); Canada (n = 4); the US (n = 37); and two of the US-based studies also had component conducted in Australia.

3.2.1. PN and Social Worker Role

In total, there were 12 papers in this topic area (Table 1), seven of which reported on the characteristics and outcomes from PN pilots/trials [19,20,21,22,23,24,25], while five reported descriptive findings to inform PN strategies [26,27,28,29,30]. From the studies that described outcomes, one reported that PN did not yield significant improvements in patient outcomes when compared to controls or standard of care [22]. However, other studies did report positive impacts of PN on various outcomes including: time to resolution following abnormal screening results [23], receiving better quality of care [24], receipt of treatment for depression and improved HRQOL [19,20,21], and a reduction in perceived distress [25]. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT) to test the effects of PN on adherence to treatment for depression among breast cancer survivors, the intervention group had more favorable depression scores and social and functional well-being at 12 months [20]. However, at 24 months, intervention and control groups received similar amounts of treatment and depression recurrence was similar between groups [19]. Finally, this RCT demonstrated that rates of unemployment, medical cost and wage concerns, and financial stress were stable through 6 months, followed by a pronounced drop at 12 months for the PN intervention group [21]. Patients reporting economic concerns had significantly poorer functional, emotional, and affective well-being. Qualitative results from this study described negative economic changes precipitated by cancer diagnosis (e.g., income decline, under employment, economic stress) [21].

Table 1.

Study Characteristics, Results Summary, and Implications.

The remaining PN studies did not include comparison groups and were descriptive in nature [28,29,30]. Retention strategies for a depression treatment program among survivors addressed barriers such as: provision of information, patient-provider relationship, and instrumental strategies (e.g., providing transportation) [30]. A study characterizing patients in a cancer nutrition rehabilitation program found that survivors with fewer psychosocial problems tended to be older (i.e., 63–94 years) and a common reason for referral to social workers was for assistance with emotional problems and coping skills related to their illness [29]. Similarly, increased age and minority race-ethnicity status were associated with higher satisfaction with cancer care among survivors receiving PN [28]. Formative research to inform PN strategies described the most common needs and services of cancer survivors, and how the network of agencies providing resources are connected [26,27]. The needs of cancer survivors revealed through focus groups included: (1) improved access to quality care; (2) emotional and practical concerns; (3) family concerns; (4) PN involvement across the continuum of care [26,27]. The composition and function of a network of service providers to help improve connectivity and referrals between agencies found that those providing informational services (e.g., health education) were more likely to refer patients and there was a need for more specialized services (e.g., prostheses, housing) [27].

3.2.2. Caregiver Role and Impact

In total there were nine papers (across eight studies) that focused on the role that caregivers play in supporting cancer survivors and impacts experienced by households (Table 1) [5,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. Seven of these papers described qualitative or quantitative results from parents of children with cancer [31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Focus groups with parents revealed both mothers and fathers reporting multiple dimensions of caregiving for their sick child (e.g., managing medications, emotional management) and parents relayed that these activities can become a full-time job, leaving little time for other activities or employment [32,33,34]. In addition, medical advocacy was described as a necessity to overcome barriers in the health care system and to ensure their child was receiving the best care possible [33]. Quantitative survey results among parents from these studies demonstrated that financial burden and hardship was experienced by parents of child cancer survivors, especially by those with lower incomes [31,35]. This financial burden was associated with loss of employment and work productivity, even for those surveyed in countries with universal health care (i.e., Canada, Australia) [35,36,37]. In addition, parents reported that loss of work productivity was associated with anxiety, depression, and negative health outcomes for themselves [38]. Families reported coping with financial hardship by fundraising and reducing spending to offset the cost of treatment [35]. Parents of children that had cancer reported the challenges that their now young adult children faced as a result of their experience as cancer survivors [36]. Some of these challenges included difficulty with employment due to disability, lack of employer support, the need for assistance from family members for activities of daily living, and financial assistance for basic necessities (e.g., clothing, food) [36].

Caregivers supporting cancer survivors also reported experiencing emotional and financial burden [5,38]. Those with greater work productivity loss tended to have increased caregiving hours, be caring for a loved one with more advanced cancer, to be married, and to report greater anxiety, depression, and burden related to financial problems [38]. Some caregivers reported that their own health suffered because they could not find the time or resources to visit a doctor when they needed [38]. One study found that surprisingly, a clearly terminal (negative) prognosis facilitated clear priorities, unambiguous emotion management, and improved social bonds while a more ambiguous (positive) prognosis fostered role conflict and clashing feelings with ongoing guilt within spousal caregivers [5].

3.2.3. Psychosocial Impacts

16 papers across 15 studies were found that described the psychosocial impacts experienced by cancer survivors (Table 1) [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. Intervention studies addressed HRQOL, stress management, and information provision [39,48,49]. A culturally sensitive telephone counseling intervention with Latina cervical cancer survivors yielded improvements in physical well-being, HRQOL, social/family wellbeing, and positive emotional effects [39]. An online health consultation to breast cancer survivors found the program improved self-efficacy, and positive perceptions of the doctor–patient relationship [49]. However, the online counseling intervention did not significantly change information seeking or perceived social support [48]. Similarly, an intervention with African American breast cancer survivors found that psychological well-being and HRQOL did not differ between the intervention and control groups, and overall improvements were attributed to factors the study could not account for [48]. A comparative study assessing differences across disease stage of prostate cancer found that men with less education experienced greater improvement in their mental well-being than did men with more than a high school education [41].

Qualitative studies with cancer survivors explored the effects of chemotherapy on cognitive functioning (i.e., “chemo brain”) [40], the experience of financial burden in cancer treatment [44], psychosocial impacts of cancer on their families [50], reasons for dropout from a depression treatment program [54], and a mixed-methods study exploring needs of African American cancer survivors [53]. Despite the differences in the purpose of these qualitative studies, all of the findings help describe the psychosocial and practical challenges that cancer survivors face [40,41,50,53,54]. Some of the challenges faced by those who underwent chemotherapy included: cognitive impairment influencing ability to manage social and professional lives; financial constraints leading to missed, delayed, or limited treatment opportunities (including long-term survivorship); family stress and lack of coping skills to deal with the effects of cancer; the need to address an array of practical needs (e.g., transportation, financial), guidance on lifestyle information, post treatment plan, and social support [40,44,50,53,54].

Several of the descriptive quantitative studies focused on identifying HRQOL and psychosocial needs of cancer survivors [42,43,45,46,47,51]. When exploring the health promoting behaviors of low-income cancer survivors, it was found that various behaviors were employed (i.e., walking, maintaining a positive mental attitude, changing their diet) [51]. In addition, participants reported spirituality as important in maintaining a hopeful and positive outlook and a desire to learn more about feasible types of exercise, healthy eating, and stress management [51]. Low-income Latina cervical cancer survivors reported high levels of depression and that immigration-related stress was common (e.g., fear of deportation, navigating a foreign medical system) [43]. Cancer-related psychosocial resources, life stress, and optimism accounted for significant proportions of the variance in psychosocial outcomes [43]. A survey with uninsured men with prostate cancer found that men with spouses were more likely to have elected surgery and have better mental health, lower symptom distress, and higher spirituality than unpartnered participants [46]. This study also found that men with prostate cancer reported worse mental health than people with other chronic diseases and that spirituality and physical functioning were positively associated with mental health [45]. In terms of race and ethnicity, in a study among African American and Latino cancer survivors it was found that African American patients with unmet supportive care and health insurance needs were more likely to miss appointments compared to Latinos [42]. Amongst Latinos, legal health-related issues predicted missed appointments [42]. Latino men with prostate cancer tended to be less educated, more often in partnered relationships, and had more variable incomes compared with men of other ethnic/racial backgrounds [47]. A survey assessing the psychosocial needs among diverse underserved cancer survivors found that ethnicity was the sole predictor of needs, even after controlling for education, time since diagnosis, treatment status, marital status, and age [52]. The needs identified included informational (e.g., treatment); practical (e.g., finances, transportation); supportive (e.g., emotional/coping support); and spiritual [52].

3.2.4. Food Insecurity and Financial Toxicity

Food insecurity and financial toxicity was described by 12 studies (Table 1) [55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66]. Survivors who reported more financial strain and burden as a result of cancer care costs were more likely to rate their physical and mental health poorer, have greater symptom burden, lower satisfaction with relationships, and lower HRQOL [55,58,59]. Those that were more likely to report experiencing material and psychological financial hardship (i.e., stress about their financial situation) were also more likely to be younger females, non-white, uninsured, treated more recently, have lower family income, and to have changed employment because of cancer [64]. Cancer survivors who reported cost-related medication nonadherence tended to be lower income, African American, and have non-employer-based medical insurance [61]. Cancer survivors that qualified for co-payment assistance reported engaging in lifestyle-altering coping strategies (spending less on leisure activities and basics like food and clothing, borrowing money, and spending savings) and care-altering coping strategies (not filling a prescription, taking less medication than prescribed) [62,65]. Participants with more education and shorter duration of chemotherapy reported using lifestyle-altering strategies more than their counterparts [62]. Two studies measured food insecurity among a sample of cancer survivors and found that these individuals had higher rates of food insecurity compared to the general population [57,63]. In addition, food insecure patients had significantly higher levels of nutritional risk (e.g., appetite, having only having liquids), depression, financial strain, lower HRQOL, and were more likely to not take prescribed medication because they reported not being able to afford it, compared to food secure patients [57,63]. Among a large cohort of cancer survivors, it was found that younger age, larger household size, and communicating with physicians about costs were associated with greater subjective financial burden [65].

Finally, descriptive studies reported findings that described the uptake of a novel emergency food system (i.e., food pantry within a hospital) [56] and the feasibility of an intervention to improve self-efficacy [60]. Results from the hospital-based food pantry pilot found that the mean number of return visits over a four-month period was 3.25 and that younger patients used the pantry less, immigrant patients used the pantry more (than US-born), and prostate cancer and later stage cancer patients used the pantry more [56]. Higher levels of education were related to higher levels of health-promoting behaviors such as reporting unusual signs or symptoms to their health professionals, questioning health professionals in order to understand instructions, and inspecting their bodies monthly for physical changes [60].

4. Discussion

Our scoping review revealed that food insecurity is an understudied challenge that is highly relevant for cancer survivors across the continuum. The American Cancer Society funded the establishment of a committee at the Institute of Medicine (IOM) to examine the range of medical and psychosocial issues faced by cancer survivors [67]. This consensus study suggests that with advances in cancer early detection and more effective treatment, long-term survivorship presents an opportunity to enhance the HRQOL across the continuum of cancer survivorship [67]. As the number of cancer survivors continue to grow and are living longer, it is important to consider the social determinants of health. Consideration of how social determinants of health (i.e., “upstream factors”) impact cancer survivors’ HRQOL will require multiple levels of analysis to understand the diverse pathways and mechanisms that link the social environment, healthcare delivery, and behavioral, psychological, and biological levels to develop more effective interventions [68]. Food insecurity may be considered a key social determinant of health [69] and is defined as the lack of consistent access to nutritionally adequate and safe food acquired in socially acceptable ways [2].

The financial impact on cancer survivors is vast and our review highlighted results from PN and social worker studies, caregiver role and impact, psychosocial impacts, and food insecurity and financial toxicity (Table 1). Only two studies in our review measured the construct of food insecurity and concluded that cancer survivors experience food insecurity at a higher rate than the general population and survivors experiencing food insecurity were also more likely to be at risk for nutritional deficiencies, depression, financial strain, and lower HRQOL [57,63]. In addition, multiple previous literature reviews concluded that there is significant employment loss for cancer survivors [12,13,14], which has logical implications for food insecurity, but has not been integrated into study methodologies.

In addition to cancer survivors being at risk for food insecurity, there is some evidence to suggest that being food insecure may place an individual at increased risk for developing cancer. A report from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) using nationally representative data found that the prevalence of cancer increases as the severity of food insecurity increases [70]. A recent commentary examined the relationships between food insecurity and cancer and explored potential mechanisms and suggested several opportunities to address food insecurity among these individuals [71]. It is suggested that care providers can help identify food insecurity through screening and referral to relevant resources and intervention [71].

This review has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. A significant limitation was the lack of published research that measured food insecurity among cancer survivors, despite evidence that the financial impact of a cancer diagnosis on a household can be catastrophic. This limited focus on the construct of food insecurity led us to establish inclusion criteria that spanned related factors (i.e., PN and social worker studies, impact on caregivers, and psychosocial/HRQOL). Moreover, many of the studies had an overall high risk of bias due to several factors such as small sample sizes, confounding, missing data, cross-sectional design, and limited generalizability. Due to the heterogeneity of study designs, we did not use formal meta-analytic techniques.

5. Conclusions

Despite these limitations, this review suggests that there are multiple ways to improve the HRQOL of cancer survivors, and many potential areas of intervention to explore. Our scoping review highlights the state of the science on food insecurity and related factors among cancer survivors and summarizes determinants of financial burden and psychosocial outcomes. Future research may want to explore, develop, and test interventions that address food insecurity among cancer survivors. Some potential areas of intervention may include screening for food insecurity and referral to relevant resources, food pantries onsite at cancer clinics and other health care settings, incorporation of food insecurity efforts into patient navigation programs, and consideration of financial burden that cancer survivors face throughout the cancer survivorship continuum. Nutrition, public health, and cancer prevention and control fields have typically grappled with food insecurity, obesity, and cancer in isolation, and have not robustly studied these factors in conjunction. The number and complexity of the reported financial burdens that cancer survivors and their caregivers face suggest that there is an urgent need for well-designed studies with appropriate methods to establish key determinants of food insecurity.

Author Contributions

C.A.P., L.R.C., K.R.S., T.L.W., C.D. and A.L.Y.: designed research (project conception, development of overall review methodologies). C.A.P., L.R.C., W.C. and T.G.: Carried out the review process including screening for article inclusion and data extraction. C.A.P. wrote the paper, provided project oversight throughout, and had primary responsibility for final content. C.A.P., L.R.C., K.R.S., W.C., T.G., T.L.W., C.D., K.K. and A.L.Y. All provided edits and contributions throughout. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the American Cancer Society.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Miller, K.D.; Siegel, R.L.; Lin, C.C.; Mariotto, A.B.; Kramer, J.L.; Rowland, J.H.; Stein, K.D.; Alteri, R.; Jemal, A. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. Cancer J. Clin. 2016, 66, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman-Jensen, A.; Rabbit, M.; Gregory, C.; Singh, A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2017, ERR-256; U.S.A. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=90022 (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- Narang, A.K.; Nicholas, L.H. Out-of-pocket spending and financial burden among Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitvogel, L.; Pietrocola, F.; Kroemer, G. Nutrition, inflammation and cancer. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, R.E.; Connor, J. When they don’t die: Prognosis ambiguity, role conflict and emotion work in cancer caregiving. J. Sociol. 2015, 51, 857–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Jemal, A.; Wender, R.C.; Gansler, T.; Ma, J.; Brawley, O.W. An assessment of progress in cancer control. Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.K.; Jemal, A. Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in cancer mortality, incidence, and survival in the United States, 1950–2014: Over six decades of changing patterns and widening inequalities. J. Environ. Public Health 2017, 2017, 2819372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.A.; Andrews, K.S.; Brooks, D.; Fedewa, S.A.; Manassaram-Baptiste, D.; Saslow, D.; Saslow, D.; Wender, R.C. Cancer screening in the United States, 2018: A review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerson, K.; Gretebeck, K. Factors influencing cancer screening practices of underserved women. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pract. 2007, 19, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coughlin, S.S.; Caplan, L.; Young, L. A review of cancer outcomes among persons dually enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid. J. Hosp. Manag. Health Policy 2018, 2, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal, C.D.; Weaver, D.T.; Raphel, T.J.; Lietz, A.P.; Flores, E.J.; Percac-Lima, S.; Knudsen, A.B.; Pandharipande, P.V. Patient navigation to improve cancer screening in underserved populations: Reported experiences, opportunities, and challenges. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2018, 15, 1565–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfano, C.M.; Kent, E.E.; Padgett, L.S.; Grimes, M.; de Moor, J.S. Making cancer rehabilitation services work for cancer patients: Recommendations for research and practice to improve employment outcomes. Contemp. Issues Cancer Rehabil. 2017, 9, S398–S406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Boer, A.G.; Taskila, T.K.; Tamminga, S.J.; Feuerstein, M.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.; Verbeek, J.H. Interventions to enhance return-to-work for cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 9, CD007569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duijts, S.; Bleiker, E.; Paalman, C.; van der Beek, A. A behavioural approach in the development of work-related interventions for cancer survivors: An exploratory review. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2017, 26, e12545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cockle-Hearne, J.; Faithfull, S. Self-management for men surviving prostate cancer: A review of behavioural and psychosocial interventions to understand what strategies can work, for whom and in what circumstances. Psycho-oncology 2010, 19, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrell, B.R.; Kravitz, K. Cancer care: Supporting underserved and financially burdened family caregivers. J. Adv. Pract. Oncol. 2017, 8, 494–500. [Google Scholar]

- Cwikel, J.G.; Behar, L.C. Organizing social work services with adult cancer patients: Integrating empirical research. Soc. Work. Health Care 1999, 28, 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert, J.R.; Braun, K.L.; Kaholokula, J.K.; Armstead, C.A.; Burch, J.B.; Thompson, B. Considering the role of stress in populations of high-risk, underserved community networks program centers. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Action 2015, 9, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ell, K.; Vourlekis, B.; Xie, B.; Nedjat-Haiem, F.R.; Lee, P.J.; Muderspach, L.; Russell, C.; Palinkas, L.A. Cancer treatment adherence among low-income women with breast or gynecologic cancer: A randomized controlled trial of patient navigation. Cancer 2009, 115, 4606–4615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ell, K.; Xie, B.; Quon, B.; Quinn, D.I.; Dwight-Johnson, M.; Lee, P.-J. Randomized controlled trial of collaborative care management of depression among low-income patients with cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 4488–4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ell, K.; Xie, B.; Wells, A.; Nedjat-Haiem, F.; Lee, P.-J.; Vourlekis, B. Economic stress among low-income women with cancer: Effects on quality of life. Cancer 2008, 112, 616–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.Y.; Evans, M.B.; Kratt, P.; Pollack, L.A.; Smith, J.L.; Oster, R.; Dingnan, M.; Prayor-Patterson, H.; Watson, C.; Houston, P.; et al. Meeting the information needs of lower income cancer survivors: Results of a randomized control trial evaluating the American cancer society’s “I Can Cope”. J. Health Commun. 2014, 19, 441–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Raich, P.C.; Whitley, E.M.; Thorland, W.; Valverde, P.; Fairclough, D. Patient navigation improves cancer diagnostic resolution: An individually randomized clinical trial in an underserved population. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2012, 21, 1629–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, A.; Ko, N.; Battaglia, T.A.; Chabner, B.A.; Moy, B. Patient navigation for underserved patients diagnosed with breast cancer. Oncologist 2012, 17, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, B.; Corsini, N.; Ramsey, I.; Edwards, S.; Ball, D.; Cocks, L.; Lill, J.; Sharplin, G.; Wilson, C. An evaluation of social work services in a cancer accommodation facility for rural South Australians. Supportive Care Cancer 2018, 26, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, C.; Darby, K.; Likes, W.; Bell, J. Social workers as patient navigators for breast cancer survivors: What do African-American medically underserved women think of this idea? Soc. Work. Health Care 2009, 48, 561–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, J.K.; Cyr, J.; Carothers, B.J.; Mueller, N.B.; Anwuri, V.V.; James, A.I. Referrals among cancer services organizations serving underserved cancer patients in an urban area. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, 1248–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean-Pierre, P.; Cheng, Y.; Wells, K.J.; Freund, K.M.; Snyder, F.R.; Fiscella, K.; Holden, A.E.; Paskett, E.; Dudley, D.; Simon, M.A.; et al. Satisfaction with cancer care among underserved racial-ethnic minorities and lower-income patients receiving patient navigation. Cancer 2016, 122, 1060–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, D.; Accurso-Massana, C.; Lechman, C.; Duder, S.; Chasen, M. Cancer nutrition rehabilitation program: The role of social work. Curr. Oncol. 2010, 17, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, A.A.; Palinkas, L.A.; Williams, S.-L.L.; Ell, K. Retaining low-income minority cancer patients in a depression treatment intervention trial: Lessons learned. Community Ment. Health J. 2015, 51, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bona, K.; London, W.B.; Guo, D.; Frank, D.A.; Wolfe, J. Trajectory of material hardship and income poverty in families of children undergoing chemotherapy: A prospective cohort study. Pediatric Blood Cancer 2016, 63, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J.N. Fathers’ home health care work when a child has cancer: I’m her dad; I have to do it. Men Masc. 2005, 7, 385–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J.N. Advocacy: Essential work for mothers of children living with cancer. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2006, 24, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, J.N. Mother’s home healthcare: Emotion work when a child has cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2006, 29, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dussel, V.; Bona, K.; Heath, J.A.; Hilden, J.M.; Weeks, J.C.; Wolfe, J. Unmeasured costs of a child’s death: Perceived financial burden, work disruptions, and economic coping strategies used by American and Australian families who lost children to cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.F.; Hasan, H.; Bobinski, M.A.; Nurcombe, W.; Olson, R.; Parkinson, M.; Goddard, K. Parents’ perspectives of life challenges experienced by long-term paediatric brain tumour survivors: Work and finances, daily and social functioning, and legal difficulties. J. Cancer Surviv. 2014, 8, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.; Lu, X.; Balsamo, L.; Devidas, M.; Winick, N.; Hunger, S.P.; Carroll, W.; Stork, L.; Maloney, K.; Kadan-Lottick, N. Family life events in the first year of acute lymphoblastic leukemia therapy: A children’s oncology group report. Pediatric Blood Cancer 2014, 61, 2277–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazanec, S.R.; Daly, B.J.; Douglas, S.L.; Lipson, A.R. Work productivity and health of informal caregivers of persons with advanced cancer. Res. Nurs. Health 2011, 34, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashing-Giwa, K.T. Enhancing physical well-being and overall quality of life among underserved Latina-American cervical cancer survivors: Feasibility study. J. Cancer Surviv. 2008, 2, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boykoff, N.; Moieni, M.; Subramanian, S.K. Confronting chemobrain: An in-depth look at survivors’ reports of impact on work, social networks, and health care response. J. Cancer Surviv. 2009, 3, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brar, R.; Maliski, S.L.; Kwan, L.; Krupski, T.L.; Litwin, M.S. Changes in quality of life among low-income men treated for prostate cancer. Urology 2005, 66, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costas-Muniz, R.; Leng, J.; Aragones, A.; Ramirez, J.; Roberts, N.; Mujawar, M.I.; Gany, F. Association of socioeconomic and practical unmet needs with self-reported nonadherence to cancer treatment appointments in low-income Latino and Black cancer patients. Ethn. Health 2016, 21, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Orazio, L.M.; Meyerowitz, B.E.; Stone, P.J.; Felix, J.; Muderspach, L.I. Psychosocial adjustment among low-income Latina cervical cancer patients. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2011, 29, 515–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darby, K.; Davis, C.; Likes, W.; Bell, J. Exploring the financial impact of breast cancer for African American medically underserved women: A qualitative study. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2009, 20, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gore, J.L.; Krupski, T.; Kwan, L.; Fink, A.; Litwin, M.S. Mental health of low income uninsured men with prostate cancer. J. Urol. 2005, 173, 1323–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, J.L.; Krupski, T.; Kwan, L.; Maliski, S.; Litwin, M.S. Partnership status influences quality of life in low-income, uninsured men with prostate cancer. Cancer 2005, 104, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupski, T.L.; Sonn, G.; Kwan, L.; Maliski, S.; Fink, A.; Litwin, M.S. Ethnic variation in health-related quality of life among low-income men with prostate cancer. Ethn. Dis. 2005, 15, 461–468. [Google Scholar]

- Lechner, S.C.; Whitehead, N.E.; Vargas, S.; Annane, D.W.; Robertson, B.R.; Carver, C.S.; Kobetz, E.; Antoni, M.H. Does a community-based stress management intervention affect psychological adaptation among underserved black breast cancer survivors? J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2014, 50, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.-Y.; Shaw, B.R.; Gustafson, D.H. Online health consultation: Examining uses of an interactive cancer communication tool by low-income women with breast cancer. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2011, 80, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, C.A.; Weihs, K.L.; Larkey, L.K.; Badger, T.A.; Koerner, S.S.; Curran, M.A.; Pedroza, R.; Garcia, F.A.R. “Like a Mexican wedding”: Psychosocial intervention needs of predominately Hispanic low-income female co-survivors of cancer. J. Fam. Nurs. 2011, 17, 380–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meraviglia, M.G.; Stuifbergen, A. Health-promoting behaviors of low-income cancer survivors. Clin. Nurse Spec. 2011, 25, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moadel, A.B.; Morgan, C.; Dutcher, J. Psychosocial needs assessment among an underserved, ethnically diverse cancer patient population. Cancer 2007, 109, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosavel, M.; Sanders, K. Needs of low-income African American cancer survivors: Multifaceted and practical. J. Cancer Educ. 2011, 26, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, A.A.; Palinkas, L.A.; Shon, E.-J.; Ell, K. Low-income cancer patients in depression treatment: Dropouts and completers. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 40, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenn, K.M.; Evans, S.B.; McCorkle, R.; DiGiovanna, M.P.; Pusztai, L.; Sanft, T.; Hofstatter, E.W.; Killelea, B.K.; Knobf, M.T.; Lannin, D.R.; et al. Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors’ quality of life. J. Oncol. Pract. 2014, 10, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gany, F.; Lee, T.; Loeb, R.; Ramirez, J.; Moran, A.; Crist, M.; McNish, T.; Leng, J.C.F. Use of hospital-based food pantries among low-income urban cancer patients. J. Community Health 2015, 40, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gany, F.; Leng, J.; Ramirez, J.; Phillips, S.; Aragones, A.; Roberts, N.; Mujawar, M.I.; Costas-Muniz, R. Health-related quality of life of food-insecure ethnic minority patients with cancer. J. Oncol. Pract. 2015, 11, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, H.P.; Carroll, N.V. Self-reported financial burden of cancer care and its effect on physical and mental health-related quality of life among US cancer survivors. Cancer 2016, 122, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lathan, C.S.; Cronin, A.; Tucker-Seeley, R.; Zafar, S.Y.; Ayanian, J.Z.; Schrag, D. Association of financial strain with symptom burden and quality of life for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 1732–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meraviglia, M.; Stuifbergen, A.; Morgan, S.; Parsons, D. Low-income cancer survivors’ use of health-promoting behaviors. MEDSURG Nurs. 2015, 24, 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Nekhlyudov, L.; Madden, J.; Graves, A.J.; Zhang, F.; Soumerai, S.B.; Ross-Degnan, D. Cost-related medication nonadherence and cost-saving strategies used by elderly Medicare cancer survivors. J. Cancer Surviv. 2011, 5, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nipp, R.D.; Zullig, L.L.; Samsa, G.; Peppercorn, J.M.; Schrag, D.; Taylor DHJr Abernethy, A.P.; Zafar, S.Y. Identifying cancer patients who alter care or lifestyle due to treatment-related financial distress. Psycho Oncol. 2016, 25, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, L.A.; Modesitt, S.C.; Brody, A.C.; Leggin, A.B. Food insecurity among cancer patients in Kentucky: A pilot study. J. Oncol. Pract. 2006, 2, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yabroff, K.R.; Dowling, E.C.; Guy, G.P.; Banegas, M.P.; Davidoff, A.; Han, X.; Virgo, K.S.; McNeel, T.S.; Chawla, N.; Blanch-Hartigan, D.; et al. Financial hardship associated with cancer in the United States: Findings from a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar, S.Y.; McNeil, R.B.; Thomas, C.M.; Lathan, C.S.; Ayanian, J.Z.; Provenzale, D. Population-based assessment of cancer survivors’ financial burden and quality of life: A prospective cohort study. J. Oncol. Pract. 2014, 11, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, S.Y.; Peppercorn, J.M.; Schrag, D.; Taylor, D.H.; Goetzinger, A.M.; Zhong, X.; Abernethy, A.P. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: A pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist 2013, 18, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine and National Research. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006.

- Hiatt, R.A.; Breen, N. The social determinants of cancer: A challenge for transdisciplinary science. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 35, S141–S150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooler, J.A.; Hartline-Grafton, H.; DeBor, M.; Sudore, R.L.; Seligman, H.K. Food insecurity: A key social determinant of health for older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 421–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, C.A.; Coleman-Jensen, A. Food Insecurity, Chronic Disease, and Health Among Working-Age Adults, ERR-235; U.S.A Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2017.

- Patel, K.G.; Borno, H.T.; Seligman, H.K. Food insecurity screening: A missing piece in cancer management. Cancer 2019, 125, 3494–3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).