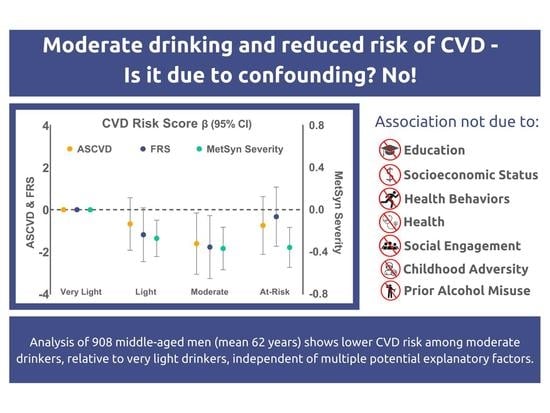

Moderate Alcohol Use Is Associated with Reduced Cardiovascular Risk in Middle-Aged Men Independent of Health, Behavior, Psychosocial, and Earlier Life Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Alcohol Use Assessment

2.3. Assessment of CVD Risk Scores

2.4. Cardiovascular Risk Factor Assessment for CVD Scores

2.5. Covariates (Grouped According to Potential Explanatory Categories)

- Base: Age, race/ethnicity, body size/composition, and behaviors.

- Socioeconomic status: Education, cognitive ability, income, financial hardship.

- Social Support: Number of confidants, closest friendship quality, marital status/quality.

- Health Status: General health, non-CVD comorbidities, depression, medications.

- Childhood factors: Childhood SES, Childhood Disadvantage Index, young adult cognitive ability.

- Prior history of alcohol misuse: Alcohol dependence, extreme binge drinking.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

- Cardiovascular Risk Factor Scores by Alcohol Group.

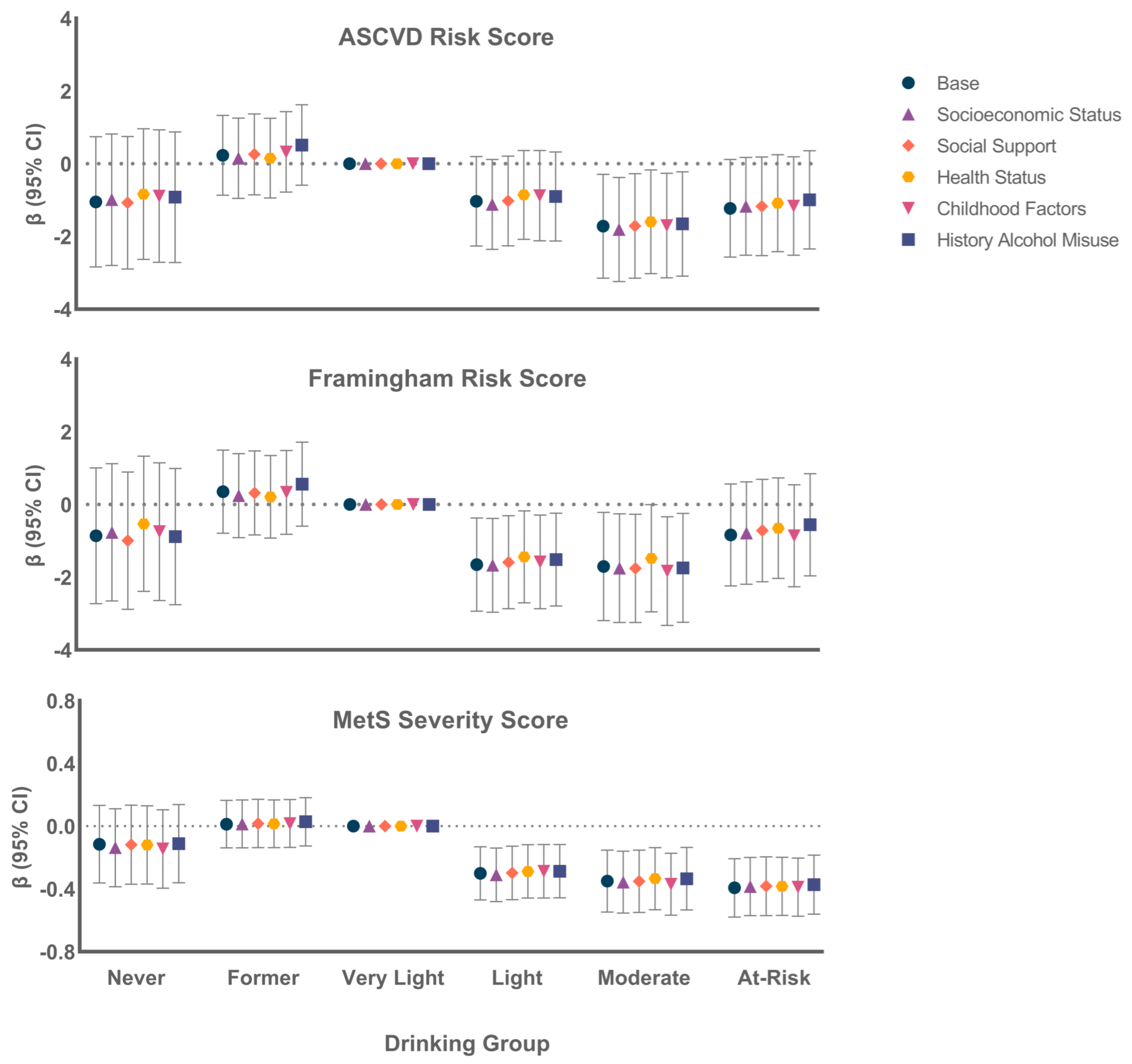

- Testing Potential Explanatory Factors

- Sensitivity Analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. CVD Risk by Alcohol Group

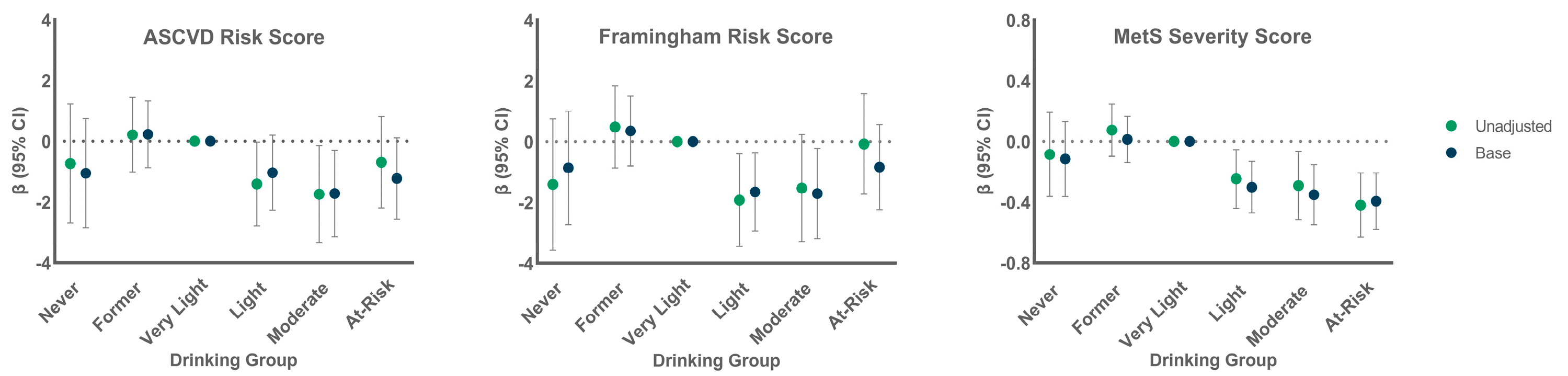

3.3. Association of Alcohol Group with Continuous CVD Risk Scores

3.4. Association of Alcohol Group with High CVD Risk

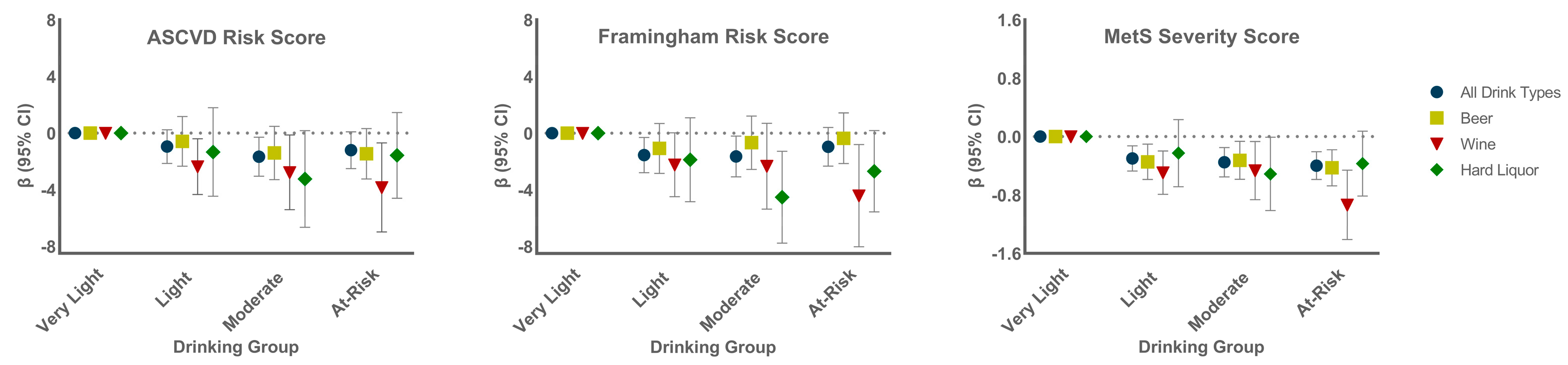

3.5. Association of Alcohol Groups with CVD Risk by Beverage Preference

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kloner, R.A.; Rezkalla, S.H. To Drink or Not to Drink? That Is the Question. Circulation 2007, 116, 1306–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neafsey, E.J.; A Collins, M. Moderate alcohol consumption and cognitive risk. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2011, 7, 465–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronksley, P.; E Brien, S.; Turner, B.J.; Mukamal, K.J.; A Ghali, W. Association of alcohol consumption with selected cardiovascular disease outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2011, 342, d671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roerecke, M.; Rehm, J. Alcohol consumption, drinking patterns, and ischemic heart disease: A narrative review of meta-analyses and a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of heavy drinking occasions on risk for moderate drinkers. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.M.; Kaptoge, S.; Butterworth, A.S.; Willeit, P.; Warnakula, S.; Bolton, T.; Paige, E.; Paul, D.S.; Sweeting, M.; Burgess, S.; et al. Risk thresholds for alcohol consumption: Combined analysis of individual-participant data for 599 912 current drinkers in 83 prospective studies. Lancet 2018, 391, 1513–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehm, J.; Rovira, P.; Llamosas-Falcón, L.; Shield, K.D. Dose–Response Relationships between Levels of Alcohol Use and Risks of Mortality or Disease, for All People, by Age, Sex, and Specific Risk Factors. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimm, E.B.; Williams, P.; Fosher, K.; Criqui, M.; Stampfer, M.J. Moderate alcohol intake and lower risk of coronary heart dis-ease: Meta-analysis of effects on lipids and haemostatic factors. BMJ 1999, 319, 1523–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.A.; Neafsey, E.J.; Mukamal, K.J.; Gray, M.O.; Parks, D.A.; Das, D.K.; Korthuis, R.J. Alcohol in Moderation, Cardioprotection, and Neuroprotection: Epidemiological Considerations and Mechanistic Studies. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2009, 33, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brien, S.E.; Ronksley, P.; Turner, B.J.; Mukamal, K.J.; Ghali, W.A. Effect of alcohol consumption on biological markers associated with risk of coronary heart disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis of interventional studies. BMJ 2011, 342, d636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, T.; Zhao, J.; Panwar, S.; Roemer, A.; Naimi, T.; Chikritzhs, T. Do “Moderate” Drinkers Have Reduced Mortality Risk? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Alcohol Consumption and All-Cause Mortality. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2016, 77, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutte, R.; Smith, L.; Wannamethee, G. Alcohol – The myth of cardiovascular protection. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 41, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Towers, A.; Philipp, M.; Dulin, P.; Allen, J. The “Health Benefits” of Moderate Drinking in Older Adults may be Better Explained by Socioeconomic Status. J. Gerontol. Ser. B: Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2016, 73, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddinger, K.J.; Emdin, C.A.; Haas, M.E.; Wang, M.; Hindy, G.; Ellinor, P.T.; Kathiresan, S.; Khera, A.V.; Aragam, K.G. Association of Habitual Alcohol Intake With Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e223849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, B.F.; Chou, S.P.; Saha, T.D.; Pickering, R.P.; Kerridge, B.T.; Ruan, W.J.; Huang, B.; Jung, J.; Zhang, H.; Fan, A.; et al. Prevalence of 12-Month Alcohol Use, High-Risk Drinking, and DSM-IV Alcohol Use Disorder in the United States, 2001–2002 to 2012–2013. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 911–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Reveals Leading Causes of Death and Disability Worldwide: 2000–2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/09-12-2020-who-reveals-leading-causes-of-death-and-disability-worldwide-2000-2019 (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Rogers, R.G.; Krueger, P.M.; Miech, R.; Lawrence, E.M.; Kemp, R. Nondrinker Mortality Risk in the United States. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2013, 32, 325–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roerecke, M.; Rehm, J. Ischemic Heart Disease Mortality and Morbidity Rates in Former Drinkers: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Epidemiology 2010, 173, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, B.; Veeranki, S.P.; Zhao, M.; Ma, C.; Yan, Y.; Mi, J. Relationship of Alcohol Consumption to All-Cause, Cardiovascular, and Cancer-Related Mortality in U.S. Adults. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, W.C.; Lui, C.K.; Williams, E.; Ye, Y.; Greenfield, T.K.; Lown, E.A. Health Risk Factors Associated with Lifetime Abstinence from Alcohol in the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth Cohort. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2017, 41, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehm, J.; Irving, H.; Ye, Y.; Kerr, W.C.; Bond, J.; Greenfield, T.K. Are Lifetime Abstainers the Best Control Group in Alcohol Epidemiology? On the Stability and Validity of Reported Lifetime Abstention. Am. J. Epidemiology 2008, 168, 866–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringhini, S.; Carmeli, C.; Jokela, M.; Avendano, M.; Muennig, P.; Guida, F.; Ricceri, F.; D’Errico, A.; Barros, H.; Bochud, M.; et al. Socioeconomic status and the 25 × 25 risk factors as determinants of premature mortality: A multicohort study and meta-analysis of 1·7 million men and women. Lancet 2017, 389, 1229–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosengren, A.; Wilhelmsen, L.; Orth-Gomér, K. Coronary disease in relation to social support and social class in Swedish men. A 15 year follow-up in the study of men born in 1933. Eur. Hear. J. 2004, 25, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikehara, S.; Iso, H.; Yamagishi, K.; Yamamoto, S.; Inoue, M.; Tsugane, S.; The JPHC Study Group. Alcohol Consumption, Social Support, and Risk of Stroke and Coronary Heart Disease Among Japanese Men: The JPHC Study. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2009, 33, 1025–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maskell, P.D.; Jones, A.W.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Shapses, S.; Johnston, A. Total body water is the preferred method to use in forensic blood-alcohol calculations rather than ethanol’s volume of distribution. Forensic Sci. Int. 2020, 316, 110532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batty, G.D.; Deary, I.; Benzeval, M.; Der, G. Does IQ predict cardiovascular disease mortality as strongly as established risk factors? Comparison of effect estimates using the West of Scotland Twenty-07 cohort study. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Prev. Rehabilitation 2010, 17, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kremen, W.S.; Franz, C.; Lyons, M. VETSA: The Vietnam Era Twin Study of Aging. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 2012, 16, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremen, W.S.; Thompson-Brenner, H.; Leung, Y.-M.J.; Grant, M.D.; Franz, C.E.; Eisen, S.A.; Jacobson, K.C.; Boake, C.; Lyons, M.J. Genes, Environment, and Time: The Vietnam Era Twin Study of Aging (VETSA). Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 2006, 9, 1009–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, R.B., Sr.; Vasan, R.S.; Pencina, M.J.; Wolf, P.A.; Cobain, M.; Massaro, J.M.; Kannel, W.B. General Cardiovascular Risk Profile for Use in Primary Care: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2008, 117, 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goff, D.C.; Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; Bennett, G.; Coady, S.; D’Agostino, R.B.; Gibbons, R.; Greenland, P.; Lackland, D.T.; Levy, D.; O’Donnell, C.J.; et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: A report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on practice guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 2935–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurka, M.J.; Lilly, C.; Oliver, M.N.; DeBoer, M.D. An examination of sex and racial/ethnic differences in the metabolic syndrome among adults: A confirmatory factor analysis and a resulting continuous severity score. Metabolism 2013, 63, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBoer, M.D.; Gurka, M.J.; Woo, J.G.; Morrison, J.A. Severity of Metabolic Syndrome as a Predictor of Cardiovascular Disease Between Childhood and Adulthood. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 66, 755–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBoer, M.D.; Gurka, M.J.; A Morrison, J.; Woo, J. Inter-relationships between the severity of metabolic syndrome, insulin and adiponectin and their relationship to future type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Int. J. Obes. 2016, 40, 1353–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeBoer, M.D.; Gurka, M.J.; Golden, S.H.; Musani, S.K.; Sims, M.; Vishnu, A.; Guo, Y.; Pearson, T.A. Independent Associations Between Metabolic Syndrome Severity and Future Coronary Heart Disease by Sex and Race. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 1204–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeBoer, M.D.; Filipp, S.L.; Sims, M.; Musani, S.K.; Gurka, M.J. Risk of Ischemic Stroke Increases Over the Spectrum of Metabolic Syndrome Severity. Stroke 2020, 51, 2548–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Musani, S.K.; Sims, M.; Pearson, T.A.; DeBoer, M.D.; Gurka, M.J. Assessing the added predictive ability of a metabolic syndrome severity score in predicting incident cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study and Jackson Heart Study. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2018, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuang, M.T.; Bar, J.L.; Harley, R.M.; Lyons, M.J. The Harvard Twin Study of Substance Abuse: What we have learned. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2001, 9, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoeneborn, C.A.; Heyman, K.M. Health characteristics of adults aged 55 years and over: United States, 2004–2007. Natl. Health Stat. Rep. 2009, 16, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Franz, C.E.; Lyons, M.J.; O’Brien, R.; Panizzon, M.S.; Kim, K.; Bhat, R.; Grant, M.D.; Toomey, R.; Eisen, S.; Xian, H.; et al. A 35-Year Longitudinal Assessment of Cognition and Midlife Depression Symptoms: The Vietnam Era Twin Study of Aging. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2011, 19, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Watson, P.; Watson, I.D.; Batt, R.D. Prediction of blood alcohol concentrations in human subjects. Updating the Widmark Equation. J. Stud. Alcohol 1981, 42, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayroff, A.G. Successive AFQT Forms: Comparisons and Evaluations; U.S. Army Personnel Research Office: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlaner, J.E. Development of the Armed Forces Qualification Test and predecessor army screening tests, 1946–1950. In PRB Technical Research Report, 976; Defense Technical Information Center: Fairfax County, VA, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Granholm, E.L.; Panizzon, M.S.; Elman, J.A.; Jak, A.J.; Hauger, R.L.; Bondi, M.W.; Lyons, M.J.; Franz, C.E.; Kremen, W.S. Pupillary Responses as a Biomarker of Early Risk for Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017, 56, 1419–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.E.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care. Med. Care 1992, 30, 473–483. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3765916 (accessed on 12 April 2022). [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingshead, A.B. Four Factor Index of Social Status; Yale University: New Haven, CT, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.; E Franz, C.; Xian, H.; Vuoksimaa, E.; Tu, X.; A Reynolds, C.; Panizzon, M.S.; McKenzie, R.M.; Lyons, M.J.; Toomey, R.; et al. Mediators of the Effect of Childhood Socioeconomic Status on Late Midlife Cognitive Abilities: A Four Decade Longitudinal Study. Innov. Aging 2018, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franz, C.E.; Spoon, K.; Thompson, W.; Hauger, R.L.; Hellhammer, D.H.; Jacobson, K.C.; Lupien, S.; Lyons, M.J.; McCaffery, J.; McKenzie, R.; et al. Adult cognitive ability and socioeconomic status as mediators of the effects of childhood disadvantage on salivary cortisol in aging adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013, 38, 2127–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Rutter, M. Family and school influences on cognitive development. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1985, 26, 683–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robins, L.; Helzer, J.; Cottler, L.; E, G. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule Version III Revised (DIS-III-R); Department of Psy-chiatry, Washington University Medical School: St. Louis, MI, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Krenz, M.; Korthuis, R.J. Moderate ethanol ingestion and cardiovascular protection: From epidemiologic associations to cellular mechanisms. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2012, 52, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arranz, S.; Chiva-Blanch, G.; Valderas-Martínez, P.; Remon, A.M.; Raventós, R.M.L.; Estruch, R. Wine, Beer, Alcohol and Polyphenols on Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer. Nutrients 2012, 4, 759–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, T.; Igarashi, M.; Yamada, S.; Takahashi, N.; Watanabe, K. Inhibitory effect of black tea and its combination with acarbose on small intestinal α-glucosidase activity. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 161, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maugeri, A.; Hlinomaz, O.; Agodi, A.; Barchitta, M.; Kunzova, S.; Bauerova, H.; Sochor, O.; Medina-Inojosa, J.; Lopez-Jimenez, F.; Vinciguerra, M.; et al. Is Drinking Alcohol Really Linked to Cardiovascular Health? Evidence from the Kardiovize 2030 Project. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeNavas-Walt, C.; Proctor, B.D.; Smith, J.C. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2010. Available online: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2011/demo/income-poverty/p60-239.html (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- An, R. Prevalence and Trends of Adult Obesity in the US, 1999–2012. ISRN Obes. 2014, 2014, 185132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslow, R.A.; Castle, I.-J.P.; Chen, C.M.; Graubard, B.I. Trends in Alcohol Consumption Among Older Americans: National Health Interview Surveys, 1997 to 2014. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2017, 41, 976–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, T.D.; Kunicki, Z.J.; Blevins, C.E.; Stein, M.D.; Marsh, E.; Feltus, S.; Miranda, R., Jr.; Thomas, J.G.; Abrantes, A.M. Prospective Associations between Attitudes toward Sweet Foods, Sugar Consumption, and Cravings for Alcohol and Sweets in Early Recovery from Alcohol Use Disorders. Alcohol. Treat. Q. 2021, 39, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jani, B.D.; McQueenie, R.; Nicholl, B.I.; Field, R.; Hanlon, P.; Gallacher, K.I.; Mair, F.S.; Lewsey, J. Association between patterns of alcohol consumption (beverage type, frequency and consumption with food) and risk of adverse health outcomes: A prospective cohort study. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Predictors | ASCVD | Framingham | MetS Severity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | X | X | |

| Sex | X | X | X |

| Race/ethnicity | X | X | |

| Waist | X | ||

| SBP, unspecified | X | ||

| SBP, treated | X | X | |

| SBP, untreated | X | X | |

| Total cholesterol | X | X | |

| HDL cholesterol | X | X | X |

| Triglycerides | X | ||

| Current Smoking | X | X | |

| Fasting glucose | X | ||

| Diabetes | X | X | |

| Outcomes predicted | 10-yr risk of nonfatal MI, CHD death, nonfatal or fatal stroke | 10-yr risk of nonfatal MI, CHD death, nonfatal or fatal stroke, transient ischemic attack, heart failure, peripheral artery disease | 10-yr risk of CVD and CHD |

| Never (n = 57) | Former (n = 266) | Very Light (n = 197) | Light (n = 165) | Moderate (n = 100) | At-Risk (n = 123) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age (yrs) | 62.5 (2.5) | 61.5 (2.5) | 61.9 (2.4) | 61.5 (2.5) | 61.7 (2.5) | 62 (2.4) | 0.87 |

| Race/ethnicity (% White) | 84 | 88 | 94 | 92 | 93 | 91 | 0.01 |

| Body Measures | |||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.2 (4.7) | 29.8 (5.5) | 29.5 (5) | 30.3 (5.2) | 30.1 (4.8) | 29.1 (4.5) | 0.22 |

| Waist girth (cm) | 40.8 (4.8) | 40.7 (5.3) | 40.6 (5.1) | 40.9 (4.8) | 40.9 (4.6) | 40 (4.8) | 0.33 |

| WHR | 0.97 (0.06) | 0.97 (0.06) | 0.96 (0.07) | 0.96 (0.06) | 0.97 (0.06) | 0.96 (0.06) | 0.27 |

| Total body water (L) | 46.2 (5.7) | 46.2 (6.4) | 46.6 (6.2) | 47.2 (6.1) | 46.9 (5.4) | 45.5 (5.5) | 0.22 |

| Health Behaviors | |||||||

| Smoking (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Never | 87 | 37 | 38 | 35 | 31 | 22 | |

| Former | 7 | 46 | 44 | 52 | 52 | 50 | |

| Current | 5 | 17 | 18 | 14 | 17 | 28 | |

| Physically active (%) | 25 | 27 | 25 | 40 | 33 | 36 | 0.02 |

| 3+ servings fruits/veg daily (%) | 39 | 29 | 38 | 38 | 36 | 28 | 0.21 |

| Socioeconomic Status | |||||||

| Education (years) | 14.2 (2.3) | 13.6 (2.1) | 13.9 (2.2) | 14.3 (2.1) | 13.9 (1.9) | 13.8 (2.2) | 0.01 |

| Wave 2 AFQT | 0.36 (0.71) | 0.33 (0.67) | 0.38 (0.68) | 0.45 (0.66) | 0.34 (0.69) | 0.26 (0.66) | 0.15 |

| Family income (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| <US $40,000 | 14 | 27 | 19 | 11 | 15 | 20 | |

| US $40,000 to $89,999 | 56 | 51 | 50 | 51 | 52 | 49 | |

| ≥US $90,000 | 30 | 22 | 30 | 38 | 33 | 32 | |

| Not enough money (%) | 11 | 24 | 13 | 14 | 18 | 13 | 0.02 |

| Difficulty paying bills (%) | 16 | 28 | 17 | 23 | 24 | 20 | 0.14 |

| Difficulty accessing medical care (%) | 2 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 0.32 |

| Social Support | |||||||

| Marital status/quality (%) | 0.02 | ||||||

| Not married | 11 | 20 | 16 | 21 | 17 | 28 | |

| Married, poor quality | 0 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 7 | |

| Married, good quality | 89 | 74 | 75 | 69 | 75 | 65 | |

| 6+ Confidants (%) | 47 | 30 | 31 | 37 | 25 | 36 | 0.07 |

| High quality closest friendship (%) | 79 | 64 | 79 | 75 | 72 | 70 | 0.013 |

| Health Status | |||||||

| SF-36 General Health Score | 70.1 (14.9) | 63.7 (17.1) | 65.6 (16.5) | 66.3 (16.1) | 69.8 (15.7) | 65.7 (14.4) | 0.02 |

| Number prescribed meds | 2.6 (2.4) | 3.8 (3.4) | 3.1 (3.1) | 2.8 (2.8) | 2.8 (3.1) | 2.7 (2.3) | <0.01 |

| Number non-CVD comorbidities | 0.58 (0.68) | 0.88 (0.97) | 0.69 (0.86) | 0.74 (0.90) | 0.72 (0.92) | 0.75 (0.82) | 0.13 |

| Depression (%) | 7 | 17 | 14 | 11 | 15 | 15 | 0.43 |

| Childhood Factors | |||||||

| Age 20 AFQT | 0.34 (0.86) | 0.28 (0.69) | 0.34 (0.70) | 0.43 (0.68) | 0.35 (0.69) | 0.32 (0.63) | 0.31 |

| Childhood SES | 32.8 (9.8) | 30.8 (10.7) | 34.2 (11.7) | 32.4 (9.9) | 32.9 (10.4) | 32.7 (12) | 0.04 |

| Childhood Disadvantage | |||||||

| Low SES father (<33) (%) | 56 | 65 | 55 | 60 | 55 | 56 | 0.63 |

| Low education mother (<HS) (%) | 45 | 40 | 37 | 32 | 29 | 36 | 0.65 |

| Large family size (5+ siblings) (%) | 34 | 39 | 35 | 31 | 40 | 38 | 0.88 |

| Family disruption (%) | 7 | 23 | 23 | 18 | 21 | 16 | 0.33 |

| CDI (0–4) | 1.37 (1.05) | 1.64 (1.13) | 1.49 (1.16) | 1.39 (1.04) | 1.44 (1.18) | 1.43 (1.22) | 0.59 |

| History of Alcohol Misuse | |||||||

| DSM-III-R Alcohol dependence (%) | 0 | 34 | 24 | 33 | 42 | 49 | 0.001 |

| Extreme binge drinking (10+/dy) (%) | 0 | 27 | 14 | 15 | 20 | 29 | 0.001 |

| Current Alcohol Use | |||||||

| Number drinks past 14 days | - | - | 2.4 (1.2) | 8.7 (2.9) | 21.1 (4.5) | 62.1 (39.8) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol type preferred (%) | 0.01 | ||||||

| Beer | - | - | 62 | 49 | 63 | 62 | |

| Wine | - | - | 21 | 31 | 19 | 13 | |

| Hard liquor | - | - | 17 | 19 | 19 | 26 |

| Risk Factor | Never (n = 57) | Former (n = 266) | Very Light (n = 197) | Light (n = 165) | Moderate (n = 100) | At-Risk (n = 123) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waist girth (cm) | 40.8 (4.8) | 40.7 (5.3) | 40.6 (5.2) | 40.9 (4.8) | 40.9 (4.6) | 40.0 (4.8) | 0.33 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 189.6 (45.1) | 180 (34.3) | 185 (38.3) | 182.6 (39.1) | 185.9 (35.4) | 194.2 (33.2) | 0.02 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 45.3 (13.8) | 44.5 (12.3) | 45.4 (11.6) | 49.1 (14) | 51.5 (15) | 58.8 (17.5) | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 116.3 (40.2) | 107.2 (30.3) | 111.6 (33.5) | 108.9 (32.6) | 109.8 (32.4) | 108.4 (29.3) | 0.29 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 151.2 (154.2) | 144.0 (91.0) | 144.4 (104.9) | 126.1 (88.6) | 123.4 (65.3) | 136.4 (84.8) | 0.08 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 101.1 (21) | 110.9 (38.2) | 111.1 (43.1) | 103.3 (21.4) | 102.9 (23.6) | 104.5 (22.4) | 0.03 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 77.5 (8.5) | 78.6 (8.3) | 78.2 (7.9) | 78.8 (9.7) | 79.2 (9) | 81.3 (8.4) | 0.07 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 124.8 (14.1) | 127.6 (15.4) | 126.8 (13.7) | 129.1 (17) | 130.1 (15.1) | 133.5 (15.9) | <0.01 |

| Anti-hypertensive Medication use (%) | 46 | 54 | 46 | 43 | 53 | 52 | 0.22 |

| Hypertension (%) | 60 | 73 | 70 | 68 | 73 | 80 | 0.18 |

| Diabetes (%) | 17 | 25 | 22 | 15 | 9 | 12 | 0.019 |

| Never (n = 57) | Former (n = 266) | Very Light (n = 197) | Light (n = 165) | Moderate (n = 100) | At-Risk (n = 123) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASCVD Risk Score | |||||||

| 10-year Risk Score | 13.5 (5.8) | 14.5 (7.3) | 14.3 (7.1) | 12.9 (6.7) | 12.5 (4.8) | 13.6 (6.0) | .13 |

| Risk ≥ 10% (%) | 68 | 71 | 75 | 59 | 66 | 66 | 0.07 |

| Framingham Risk Score | |||||||

| 10-year Risk Score | 18.4 (7.4) | 20.3 (7.4) | 19.8 (7.2) | 17.9 (7.5) | 18.3 (6.9) | 19.7 (7.5) | 0.01 |

| Risk ≥ 20% (%) | 40 | 50 | 47 | 35 | 34 | 47 | 0.01 |

| MetS Severity Score | |||||||

| Z-Score (SDs) | 0.34 (0.89) | 0.50 (0.93) | 0.43 (1.09) | 0.18 (0.85) | 0.14 (0.82) | 0.01 (0.91) | <0.001 |

| Z-Score ≥ 0.5 SD (%) | 46 | 46 | 39 | 32 | 28 | 29 | 0.002 |

| Never (n = 57) | Former (n = 266) | Very Light (n = 197) | Light (n = 165) | Moderate (n = 100) | At-Risk (n = 123) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| ASCVD Score ≥ 10% | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.71 (0.38–1.36) | 0.83 (0.54–1.27) | Ref | 0.48 (0.31–0.75) | 0.64 (0.37–1.10) | 0.64 (0.38–1.07) |

| Base | 0.54 (0.25–1.17) | 0.83 (0.50–1.37) | Ref | 0.48 (0.29–0.78) | 0.61 (0.31–1.18) | 0.44 (0.25–0.78) |

| + Socioeconomic Status | 0.53 (0.24–1.15) | 0.76 (0.45–1.26) | Ref | 0.48 (0.29–0.78) | 0.60 (0.30–1.17) | 0.43 (0.24–0.76) |

| + Social Support | 0.52 (0.24–1.16) | 0.84 (0.50–1.41) | Ref | 0.49 (0.30–0.80) | 0.59 (0.30–1.16) | 0.46 (0.26–0.83) |

| + Health Status | 0.57 (0.26–1.25) | 0.84 (0.50–1.41) | Ref | 0.51 (0.31–0.83) | 0.63 (0.32–1.22) | 0.45 (0.25–0.79) |

| + Childhood Factors | 0.55 (0.25–1.22) | 0.81 (0.49–1.35) | Ref | 0.48 (0.29–0.78) | 0.60 (0.30–1.13) | 0.43 (0.24–0.76) |

| + History Alcohol Misuse | 0.51 (0.23–1.13) | 0.86 (0.52–1.43) | Ref | 0.49 (0.30–0.80) | 0.60 (0.31–1.18) | 0.47 (0.26–0.84) |

| FRS ≥ 20% | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.74 (0.38–1.45) | 1.08 (0.74–1.57) | Ref | 0.59 (0.39–0.90) | 0.56 (0.34–0.95) | 0.98 (0.62–1.55) |

| Base | 0.76 (0.36–1.53) | 1.06 (0.70–1.61) | Ref | 0.54 (0.34–0.86) | 0.43 (0.22–0.83) | 0.81 (0.48–1.36) |

| + Socioeconomic Status | 0.79 (0.37–1.66) | 1.03 (0.68–1.58) | Ref | 0.54 (0.34–0.85) | 0.42 (0.21–0.83) | 0.82 (0.49–1.37) |

| + Social Support | 0.75 (0.34–1.63) | 1.03 (0.67–1.58) | Ref | 0.55 (0.34–0.87) | 0.42 (0.21–0.89) | 0.82 (0.49–1.41) |

| + Health Status | 0.87 (0.41–1.87) | 1.02 (0.67–1.55) | Ref | 0.57 (0.36–0.92) | 0.44 (0.23–0.87) | 0.86 (0.51–1.46) |

| + Childhood Factors | 0.80 (0.38–1.71) | 1.04 (0.68–1.58) | Ref | 0.55 (0.34–0.87) | 0.40 (0.21–0.80) | 0.79 (0.47–1.33) |

| + History Alcohol Misuse | 0.76 (0.35–1.65) | 1.12 (0.73–1.73) | Ref | 0.56 (0.35–0.90) | 0.42 (0.21–0.82) | 0.88 (0.52–1.51) |

| MetS Severity Score ≥ 0.5 SD | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.31 (0.72–2.39) | 1.34 (0.92–1.96) | Ref | 0.71 (0.46–1.11) | 0.60 (0.35–1.04) | 0.64 (0.39–1.06) |

| Base | 1.26 (0.67–2.40) | 1.28 (0.82–2.00) | Ref | 0.57 (0.34–0.95) | 0.46 (0.24–0.88) | 0.64 (0.36–1.14) |

| + Socioeconomic Status | 1.32 (0.67–2.60) | 1.31 (0.84–2.05) | Ref | 0.57 (0.34–0.95) | 0.44 (0.23–0.86) | 0.60 (0.34–1.08) |

| + Social Support | 1.33 (0.68–2.60) | 1.31 (0.83–2.08) | Ref | 0.57 (0.34–0.97) | 0.45 (0.23–0.88) | 0.64 (0.36–1.13) |

| + Health Status | 1.33 (0.68–2.59) | 1.32 (0.84–2.07) | Ref | 0.59 (0.35–0.99) | 0.47 (0.24–0.92) | 0.61 (0.34–1.10) |

| + Childhood Factors | 1.31 (0.66–2.60) | 1.36 (0.86–2.14) | Ref | 0.62 (0.37–1.04) | 0.44 (0.22–0.86) | 0.62 (0.35–1.12) |

| + History Alcohol Misuse | 1.34 (0.68–2.64) | 1.36 (0.86–2.13) | Ref | 0.59 (0.35–0.99) | 0.48 (0.24–0.94) | 0.64 (0.36–1.14) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McEvoy, L.K.; Bergstrom, J.; Tu, X.; Garduno, A.C.; Cummins, K.M.; Franz, C.E.; Lyons, M.J.; Reynolds, C.A.; Kremen, W.S.; Panizzon, M.S.; et al. Moderate Alcohol Use Is Associated with Reduced Cardiovascular Risk in Middle-Aged Men Independent of Health, Behavior, Psychosocial, and Earlier Life Factors. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2183. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14112183

McEvoy LK, Bergstrom J, Tu X, Garduno AC, Cummins KM, Franz CE, Lyons MJ, Reynolds CA, Kremen WS, Panizzon MS, et al. Moderate Alcohol Use Is Associated with Reduced Cardiovascular Risk in Middle-Aged Men Independent of Health, Behavior, Psychosocial, and Earlier Life Factors. Nutrients. 2022; 14(11):2183. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14112183

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcEvoy, Linda K., Jaclyn Bergstrom, Xinming Tu, Alexis C. Garduno, Kevin M. Cummins, Carol E. Franz, Michael J. Lyons, Chandra A. Reynolds, William S. Kremen, Matthew S. Panizzon, and et al. 2022. "Moderate Alcohol Use Is Associated with Reduced Cardiovascular Risk in Middle-Aged Men Independent of Health, Behavior, Psychosocial, and Earlier Life Factors" Nutrients 14, no. 11: 2183. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14112183

APA StyleMcEvoy, L. K., Bergstrom, J., Tu, X., Garduno, A. C., Cummins, K. M., Franz, C. E., Lyons, M. J., Reynolds, C. A., Kremen, W. S., Panizzon, M. S., & Laughlin, G. A. (2022). Moderate Alcohol Use Is Associated with Reduced Cardiovascular Risk in Middle-Aged Men Independent of Health, Behavior, Psychosocial, and Earlier Life Factors. Nutrients, 14(11), 2183. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14112183