Breakfast Frequency and Composition in a Group of Polish Children Aged 7–10 Years

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Settings

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Data Analysis and Presentation

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Size and Demographic

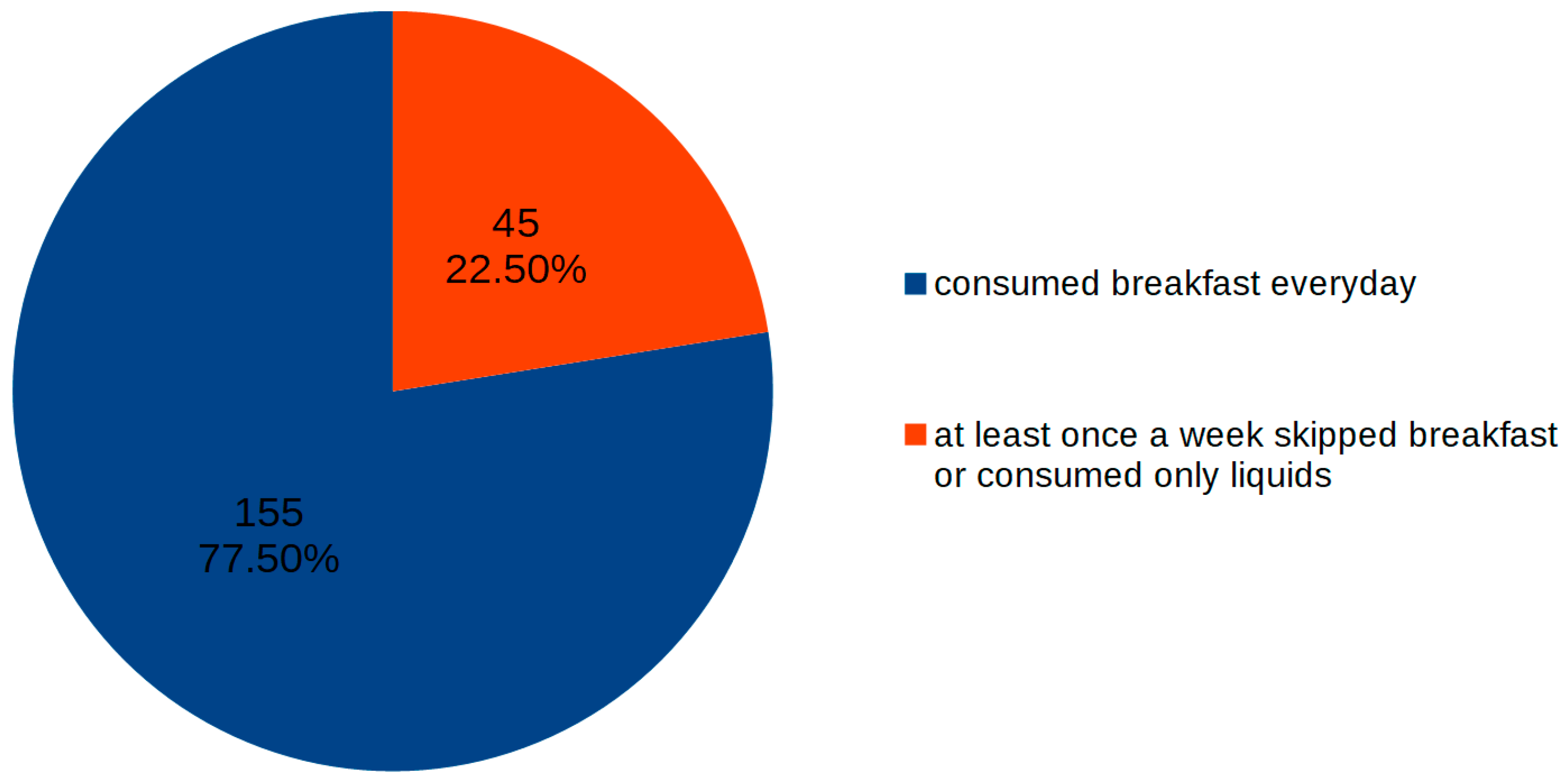

3.2. Breakfast Regular Consumption and Breakfast Skipping

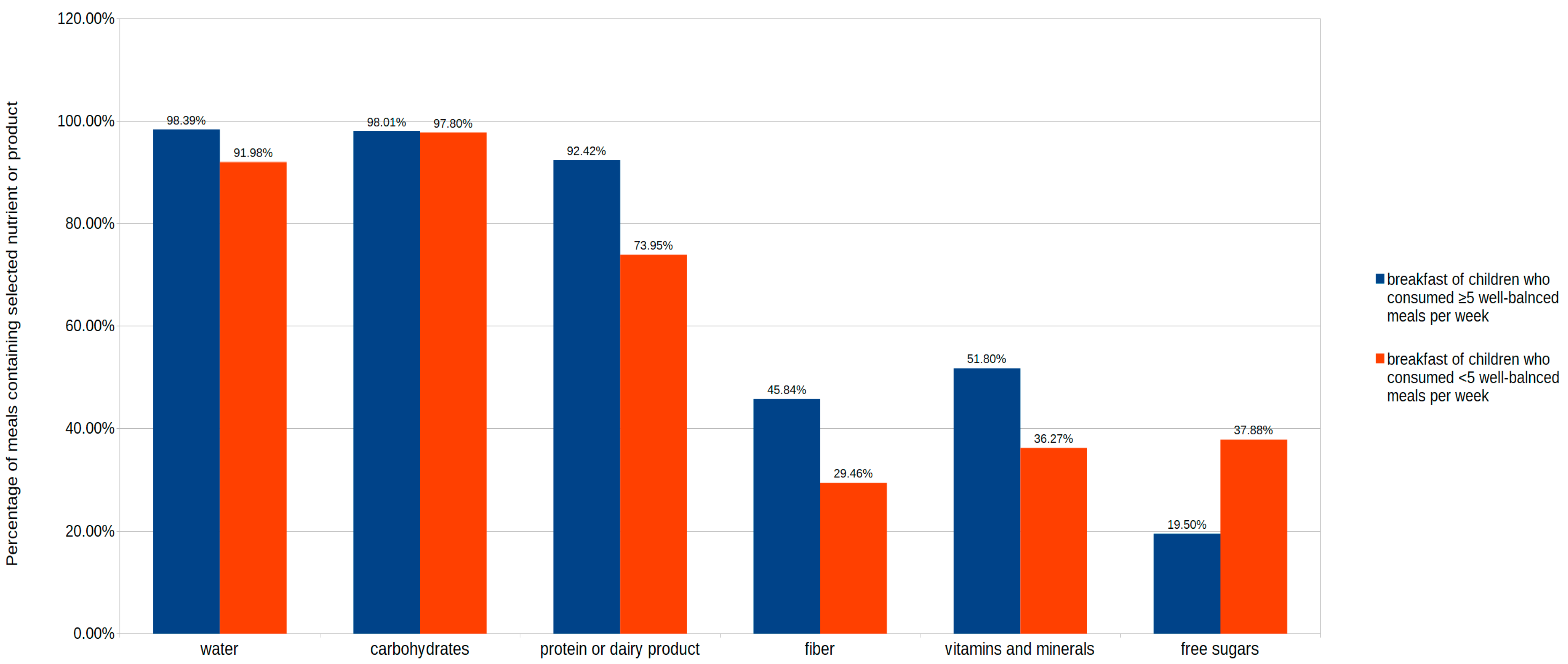

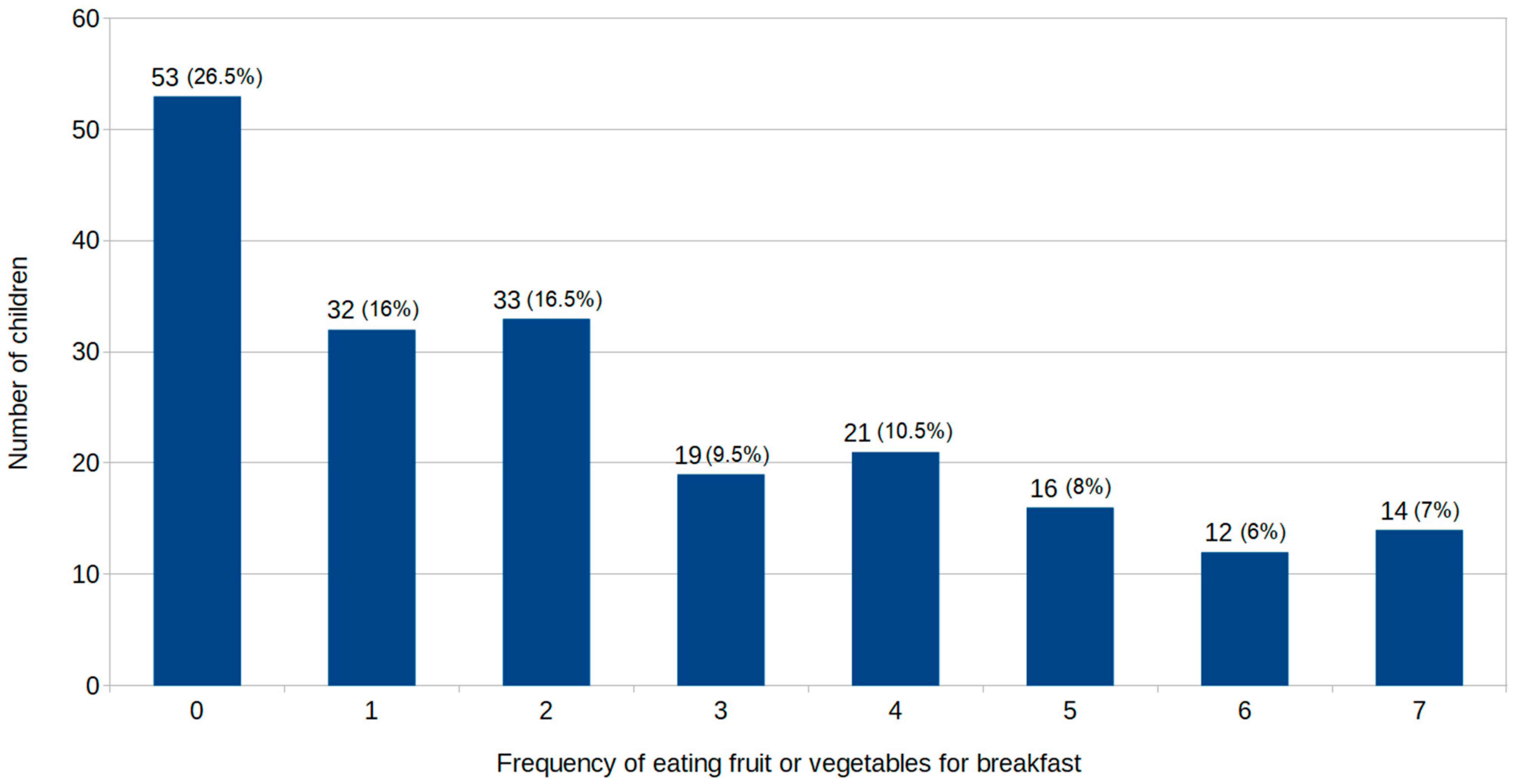

3.3. Breakfast Composition—Qualitative Assessment

3.4. Breakfast Patterns

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Affenito, S.G. Breakfast: A Missed Opportunity. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2007, 107, 565–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rampersaud, G.C. Benefits of Breakfast for Children and Adolescents: Update and Recommendations for Practitioners. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2008, 3, 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipp, A.; Eissing, G. Studies on the influence of breakfast on the mental performance of school children and adolescents. J. Public Health 2019, 27, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, D.; Jarvis, M. The role of breakfast and a mid-morning snack on the ability of children to concentrate at school. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 90, 382–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pivik, R.T.; Tennal, K.B.; Chapman, S.D.; Gu, Y. Eating breakfast enhances the efficiency of neural networks engaged during mental arithmetic in school-aged children. Physiol. Behav. 2012, 106, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolphus, K.; Lawton, C.L.; Dye, L. The effects of breakfast on behaviour and academic performance in children and adolescents. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Szajewska, H.; Ruszczyński, M. Systematic review demonstrating that breakfast consumption influences body weight outcomes in children and adolescents in Europe. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2010, 50, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.A.; Padez, C.; Sartorelli, D.S.; Oliveira, R.M.S.; Netto, M.P.; Mendes, L.L.; Candido, A.P.C. Cross-sectional study showed that breakfast consumption was associated with demographic, clinical and biochemical factors in children and adolescents. Acta Paediatr. 2018, 107, 1562–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadolowska, L.; Hamulka, J.; Kowalkowska, J.; Ulewicz, N.; Gornicka, M.; Jeruszka-Bielak, M.; Kostecka, M.; Wawrzyniak, A. Skipping breakfast and a meal at school: Its correlates in adiposity context. report from the ABC of healthy eating study of polish teenagers. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ardeshirlarijani, E.; Namazi, N.; Jabbari, M.; Zeinali, M.; Gerami, H.; Jalili, R.B.; Larijani, B.; Azadbakht, L. The link between breakfast skipping and overweigh/obesity in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2019, 18, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Gibson, D.; Stearne, K.; Dobbin, S.W. Skipping breakfast and non–high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level in school children: A preliminary analysis. Public Health 2019, 168, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh-Taskar, P.R.; Nicklas, T.A.; O’Neil, C.E.; Keast, D.R.; Radcliffe, J.D.; Cho, S. The Relationship of Breakfast Skipping and Type of Breakfast Consumption with Nutrient Intake and Weight Status in Children and Adolescents: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2006. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giménez-Legarre, N.; Flores-Barrantes, P.; Miguel-Berges, M.L.; Moreno, L.A.; Santaliestra-Pasías, A.M. Breakfast Characteristics and Their Association with Energy, Macronutrients, and Food Intake in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inchley, J.; Currie, D.; Budisavljevic, S.; Torsheim, T.; Jåstad, A.; Cosma, A. Spotlight on Adolescent Health and Well-Being: Findings from the 2017/2018 Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Survey in Europe and Canada; International Report; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, T.P.; Holstein, B.E.; Flachs, E.M.; Rasmussen, M. Meal frequencies in early adolescence predict meal frequencies in late adolescence and early adulthood. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lepicard, E.M.; Maillot, M.; Vieux, F.; Viltard, M.; Bonnet, F. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of breakfast nutritional composition in French schoolchildren aged 9–11 years. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 30, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bellisle, F.; Hébel, P.; Salmon-Legagneur, A.; Vieux, F. Breakfast Consumption in French Children, Adolescents, and Adults: A Nationally Representative Cross-Sectional Survey Examined in the Context of the International Breakfast Research Initiative. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Afeiche, M.C.; Taillie, L.S.; Hopkins, S.; Eldridge, A.L.; Popkin, B.M. Breakfast Dietary Patterns among Mexican Children Are Related to Total-Day Diet Quality. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiso, D.; Baldini, M.; Piaggesi, N.; Ferrari, P.; Biagi, P.; Malaguti, M.; Lorenzini, A. “7 days for my health”: A new tool to evaluate kids’ lifestyle. Agro. Food Ind. Hi Tech 2010, 21, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Catalani, F.; Gibertoni, D.; Lorusso, G.; Rangone, M.; Dallolio, L.; Todelli, S.; Lorenzini, A.; Tiso, D.; Marini, S.; Leoni, E. Consumo e adeguatezza della prima colazione durante l’arco di una settimana in un campione di bambini della scuola primaria. In Proceedings of the 51 Congresso Nazionale Societa Italiana di Igiene Abstract Book, Riva del Garda, Italy, 17–20 October 2018; p. 519. [Google Scholar]

- Healthy Eating Recommendations: Plate of Healthy Eating. Available online: https://ncez.pzh.gov.pl/abc-zywienia/talerz-zdrowego-zywienia/ (accessed on 15 June 2021). (In Polish)

- Pyramid of Healthy Nutrition and Physical Activity for Children. Available online: http://www.izz.waw.pl/strona-gowna/3-aktualnoci/aktualnoci/643-piramida-zdrowego-zywienia-i-stylu-zycia-dzieci-i-mlodziezy (accessed on 15 June 2021). (In Polish).

- Fijałkowska, A.; Oblacińska, A.; Stalmach, M. Nadwaga i otyłość u polskich 8-latków w świetle uwarunkowań biologicznych behawioralnych i społecznych. Raport z międzynarodowych badań WHO Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (COSI). In Overweight and Obesity among Polish 8-Year-Olds in the Context of Biological, Behavioural and Social Determinants; Report from International WHO Research Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (COSI); Instytut Matki i Dziecka: Warsaw, Poland, 2017; pp. 72–86. [Google Scholar]

- Zielińska, M.; Hamułka, J.; Gajda, K. Family influences on breakfast frequency and quality among primary school pupils in Warsaw and its surrounding areas. Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig. 2015, 66, 143–149. [Google Scholar]

- Galczak-Kondraciuk, A.; Stempel, P.; Czeczelewski, J. Assessment of nutritional behaviours of children aged 7–12 attending to primary schools in Biala Podlaska, Poland. Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig. 2018, 69, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Ostachowska-Gasior, A.; Piwowar, M.; Kwiatkowski, J.; Kasperczyk, J.; Skop-Lewandowska, A. Breakfast and Other Meal Consumption in Adolescents from Southern Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Papoutsou, S.; Briassoulis, G.; Hadjigeorgiou, C.; Savva, S.C.; Solea, T.; Hebestreit, A.; Pala, V.; Sieri, S.; Kourides, Y.; Kafatos, A.; et al. The combination of daily breakfast consumption and optimal breakfast choices in childhood is an important public health message. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 65, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vissers, P.A.J.; Jones, A.P.; Corder, K.; Jennings, A.; Van Sluijs, E.M.F.; Welch, A.; Cassidy, A.; Griffin, S. Breakfast consumption and daily physical activity in 9-10-year-old British children. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 1281–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- ALBashtawy, M. Breakfast Eating Habits Among Schoolchildren. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2017, 36, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koca, T.; Akcam, M.; Serdaroglu, F.; Dereci, S. Breakfast habits, dairy product consumption, physical activity, and their associations with body mass index in children aged 6–18. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2017, 176, 1251–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramotowska, A.; Szypowski, W.; Kunecka, K.; Szypowska, A. Ocena czynników wpływających na konsumpcję śniadań wśród warszawskiej młodzieży w wieku szkolnym—rola w prewencji otyłości the assessment of the factors affecting breakfast habits in youth living in Warsaw, the role in obesity prevention. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2017, 16, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullan, B.A.; Singh, M. A systematic review of the quality, content, and context of breakfast consumption. Nutr. Food Sci. 2010, 40, 81–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alexy, U.; Wicher, M.; Kersting, M. Breakfast trends in children and adolescents: Frequency and quality. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 1795–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raaijmakers, L.G.M.; Bessems, K.M.H.H.; Kremers, S.P.J.; Van Assema, P. Breakfast consumption among children and adolescents in the Netherlands. Eur. J. Public Health 2010, 20, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rito, A.I.; Dinis, A.; Rascôa, C.; Maia, A.; de Carvalho Martins, I.; Santos, M.; Lima, J.; Mendes, S.; Padrão, J.; Stein-Novais, C. Improving breakfast patterns of portuguese children—An evaluation of ready-to-eat cereals according to the European nutrient profile model. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 73, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, L. The Importance of Breakfast in Europe. In A Review of National Policies and Health Campaigns; Breakfast is Best: Brusesels, Belgium, 2017; pp. 36–37. Available online: http://www.breakfastisbest.eu/docs/102017/BIB_Report_Importance_of_Breakfast_in_Europe_2017.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2021).

| Type of Observation for Breakfast Consumption | Number of Observations | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Solid food with or without beverage | 1304 | 93.14% |

| Only liquids | 79 | 5.64% |

| No breakfast | 17 | 1.21% |

| Total | 1400 | 100% |

| Variables | Children Who Consumed Breakfast Every Day during the Week | Children Who Skipped Breakfast or Consumed Only Liquids at Least Once during the Week | p-Value | Children Who Consumed Well-Balanced Breakfast ≥ 5 Times per Week | Children Who Consumed Well-Balanced Breakfast < 5 Times per Week | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Sample size | 155 | 45 | 117 | 83 | ||||||

| Sex girls boys | 90 65 | 58.06% 41.94% | 24 21 | 53.33% 46.67% | 0.573 | 61 56 | 52.14% 47.86% | 53 30 | 63.86% 36.14% | 0.099 |

| Mean age (years) | 8.6 | 8.73 | 0.256 | 8.63 | 8.66 | 0.705 | ||||

| Time Period | Yes | No | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| School days | 60 (30%) | 86 (43%) | 0.007 |

| Weekend days | 140 (70%) | 114 (57%) |

| Variables | Children Who Consumed Well-Balanced Breakfast ≥ 5 Times per Week | Children Who Consumed Well-Balanced Breakfast < 5 Times per Week | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Content of selected food items in meals | |||||

| number of observations | 805 | 100% | 499 | 100% | |

| sandwich | 509 | 63.23% | 287 | 57.52% | 0.040 |

| sweet roll/bun | 22 | 2.73% | 21 | 4.21% | 0.147 |

| cereals or porridge | 225 | 27.95% | 80 | 16.03% | <0.001 |

| yogurt | 150 | 18.63% | 82 | 16.43% | 0.313 |

| eggs | 105 | 13.04% | 70 | 14.03% | 0.612 |

| vegetables | 204 | 25.24% | 60 | 12.02% | <0.001 |

| fruit | 194 | 24.10% | 85 | 17.03% | 0.002 |

| fruit or vegetables | 361 | 44.84% | 128 | 25.65% | <0.001 |

| other | 18 | 2.24% | 22 | 4.41% | 0.027 |

| Content of selected beverage items in meals | |||||

| number of observations | 817 | 100% | 566 | 100% | |

| water | 322 | 39.41% | 149 | 26.33% | <0.001 |

| tea | 295 | 36.11% | 203 | 35.87% | 0.927 |

| milk | 275 | 33.66% | 105 | 18.55% | <0.001 |

| cacao | 49 | 6% | 81 | 14.31% | <0.001 |

| fruit juice in a carton | 115 | 14.08% | 48 | 8.48% | 0.002 |

| fresh cold-pressed fruit juice | 22 | 2.69% | 25 | 4.42% | 0.082 |

| sweet drink | 40 | 4.9% | 32 | 5.65% | 0.533 |

| other | 6 | 0.73% | 12 | 2.12% | 0.025 |

| Food Item | Children Who Consumed Well-Balanced Breakfast ≥ 5 Times per Week | Children Who Consumed Well-Balanced Breakfast < 5 Times per Week | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| sandwich | 0.006 | ||

| M ± | 4.35 ± 2.35 | 3.46 ± 2.09 | |

| Me | 5 | 3 | |

| Min-Max | 0–7 | 0–7 | |

| sweet roll/bun | 0.515 | ||

| M ± | 0.19 ± 0.68 | 0.25 ± 0.71 | |

| Me | 0 | 0 | |

| Min-Max | 0–5 | 0–4 | |

| cereals or porridge | <0.001 | ||

| M ± | 1.92 ± 2.19 | 0.96 ± 1.58 | |

| Me | 1 | 0 | |

| Min-Max | 0–7 | 0–7 | |

| yogurt | 0.224 | ||

| M ± | 1.28 ± 1.89 | 0.99 ± 1.32 | |

| Me | 0 | 0 | |

| Min-Max | 0–7 | 0–7 | |

| eggs | 0.695 | ||

| M ± | 0.90 ± 0.97 | 0.84 ± 0.94 | |

| Me | 1 | 1 | |

| Min-Max | 0–3 | 0–4 | |

| vegetables | <0.001 | ||

| M ± | 1.74 ± 1.86 | 0.72 ± 1.24 | |

| Me | 1 | 0 | |

| Min-Max | 0–7 | 0–5 | |

| fruit | 0.015 | ||

| M ± | 1.66 ± 2.01 | 1.02 ± 1.46 | |

| Me | 1 | 0 | |

| Min-Max | 0–7 | 0–5 | |

| fruit or vegetables | <0.001 | ||

| M ± | 3.09 ± 2.33 | 1.54 ± 1.73 | |

| Me | 3 | 1 | |

| Min-Max | 0–7 | 0–6 |

| Beverage Item | Children Who Consumed Well-Balanced Breakfast ≥ 5 Times per Week | Children Who Consumed Well-Balanced Breakfast < 5 Times per Week | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| water | 0.011 | ||

| M ± | 2.75 ± 2.73 | 1.80 ± 2.43 | |

| Me | 2 | 0 | |

| Min-Max | 0–7 | 0–7 | |

| tea | 0.841 | ||

| M ± | 2.52 ± 2.67 | 2.45 ± 2.55 | |

| Me | 2 | 2 | |

| Min-Max | 0–7 | 0–7 | |

| milk | <0.001 | ||

| M ± | 2.35 ± 2.24 | 1.27 ±1.79 | |

| Me | 2 | 0 | |

| Min-Max | 0–7 | 0–7 | |

| cacao | 0.009 | ||

| M ± | 0.42 ± 0.98 | 0.98 ± 1.97 | |

| Me | 0 | 0 | |

| Min-Max | 0–7 | 0–7 | |

| juice | 0.073 | ||

| M ± | 0.98 ± 1.85 | 0.58 ± 1.04 | |

| Me | 0 | 0 | |

| Min-Max | 0–7 | 0–5 | |

| sweet drink | 0.804 | ||

| M ± | 0.34 ± 1.25 | 0.39 ± 1.20 | |

| Me | 0 | 0 | |

| Min-Max | 0–7 | 0–6 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kawalec, A.; Pawlas, K. Breakfast Frequency and Composition in a Group of Polish Children Aged 7–10 Years. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2241. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072241

Kawalec A, Pawlas K. Breakfast Frequency and Composition in a Group of Polish Children Aged 7–10 Years. Nutrients. 2021; 13(7):2241. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072241

Chicago/Turabian StyleKawalec, Anna, and Krystyna Pawlas. 2021. "Breakfast Frequency and Composition in a Group of Polish Children Aged 7–10 Years" Nutrients 13, no. 7: 2241. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072241

APA StyleKawalec, A., & Pawlas, K. (2021). Breakfast Frequency and Composition in a Group of Polish Children Aged 7–10 Years. Nutrients, 13(7), 2241. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072241