Fat, Sugar or Gut Microbiota in Reducing Cardiometabolic Risk: Does Diet Type Really Matter?

Abstract

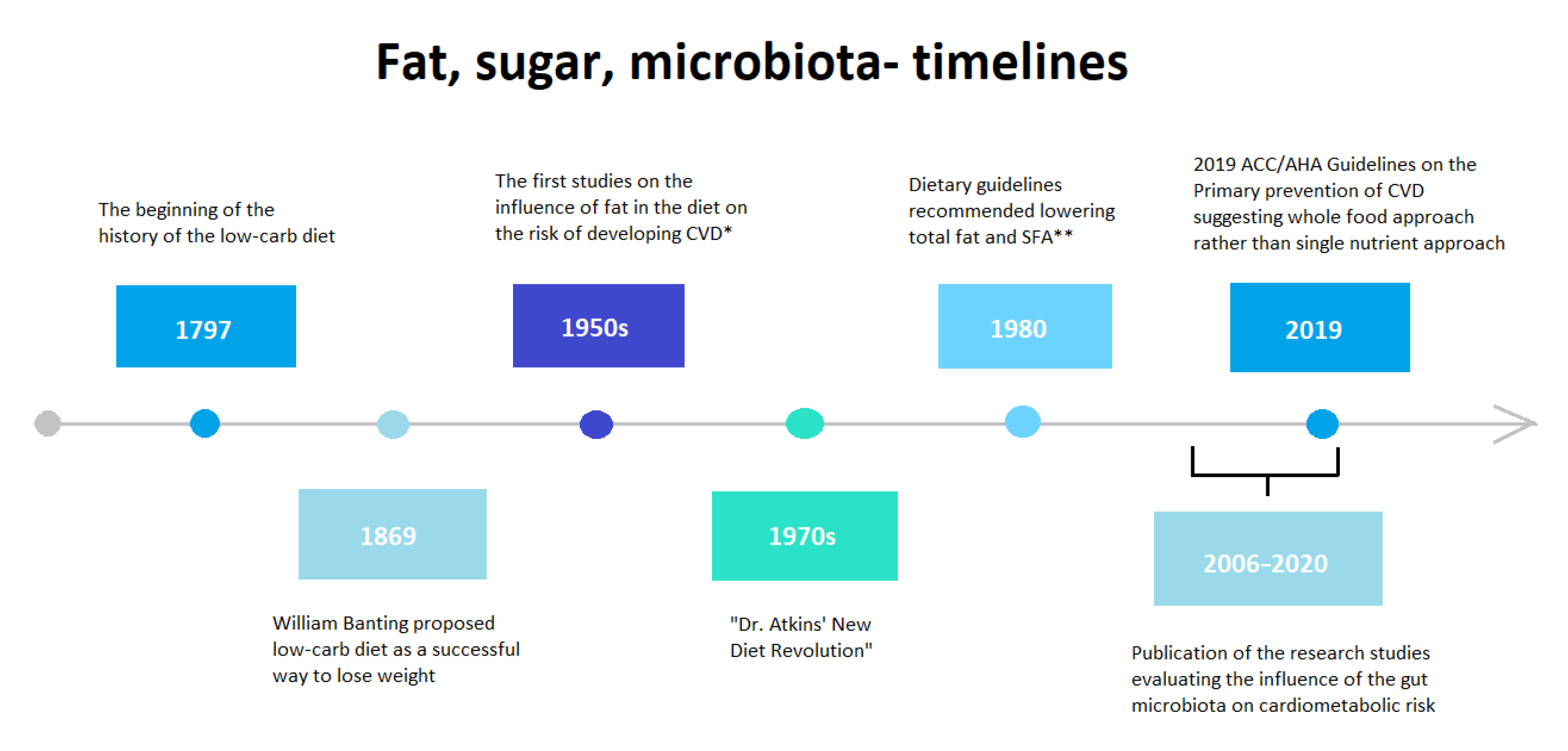

1. Introduction

2. Epidemiological Insights

3. Low-Fat Diet and Obesity

4. Low-Fat Diet in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

5. Low-Fat Diet and Cardiovascular Risk

6. Low-Carbohydrate Diet in Obesity

7. Low-Carbohydrate Diet in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

8. Low-Carbohydrate Diet and Cardiovascular Risk

9. Fat and Sugar—New Insights

10. Low-Fat, Low-Carbohydrate Diets in Relation to Microbiota in Cardiometabolic Risk

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Hu, F.B. Epidemiology of Obesity and Diabetes and Their Cardiovascular Complications. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 1723–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, Z.J.; Bleich, S.N.; Cradock, A.L.; Barrett, J.L.; Giles, C.M.; Flax, C.; Long, M.W.; Gortmaker, S.L. Projected U.S. State-Level Prevalence of Adult Obesity and Severe Obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2440–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 9th edn. Brussels, Belgium: 2019. Available online: https://www.diabetesatlas.org (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Micha, R.; Peñalvo, J.L.; Cudhea, F.; Imamura, F.; Rehm, C.D.; Mozaffarian, D. Association Between Dietary Factors and Mortality From Heart Disease, Stroke, and Type 2 Diabetes in the United States. JAMA 2017, 317, 912–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Wan, Y.; Tang, J.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Yuan, J.; Wang, F.; Li, D. Contribution of diet to gut microbiota and related host cardiometabolic health: Diet-gut interaction in human health. Gut Microbes 2020, 11, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalen, J.E.; Alpert, J.S.; Goldberg, R.J.; Weinstein, R.S. The epidemic of the 20(th) century: Coronary heart disease. Am. J. Med. 2014, 127, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinov, I.E.; Jankovic, G.M.; Alexander, I. Ignatowski: A pioneer in the study of atherosclerosis. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2013, 40, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buttar, H.S.; Li, T.; Ravi, N. Prevention of cardiovascular diseases: Role of exercise, dietary interventions, obesity and smoking cessation. Exp. Clin. Cardiol. 2005, 10, 229–249. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sacks, F.M.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Wu, J.H.Y.; Appel, L.J.; Creager, M.A.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Miller, M.; Rimm, E.B.; Rudel, L.L.; Robinson, J.G.; et al. Dietary Fats and Cardiovascular Disease: A Presidential Advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017, 136, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keys, A.; Aravanis, C.; Blackburn, H.W.; Van Buchem, F.S.; Buzina, R.; Djordjević, B.D.; Dontas, A.S.; Fidanza, F.; Karvonen, M.J.; Kimura, N.; et al. Epidemiological studies related to coronary heart disease: Characteristics of men aged 40–59 in seven countries. Acta Medica Scand. Suppl. 1966, 460, 1–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keys, A.; Anderson, J.T.; Grande, F. Prediction of serum-cholesterol responses of man to changes in fats in the diet. Lancet 1957, 273, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekelle, R.B.; Shryock, A.M.; Paul, O.; Lepper, M.; Stamler, J.; Liu, S.; Raynor, W.J., Jr. Diet, serum cholesterol, and death from coronary heart disease. The Western Electric study. N. Engl. J. Med. 1981, 304, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, I.H.; Allen, E.V.; Chamberlain, F.L.; Keys, A.; Stamler, J.; Stare, F.J. Dietary Fat and Its Relation to Heart Attacks and Strokes. Circulation 1961, 23, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keys, A. Coronary heart disease in seven countries. 1970. Nutrition 1997, 13, 250–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keys, A. Mediterranean diet and public health: Personal reflections. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 1995, 61 (Suppl. 6), 1321S–1323S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salas-Salvadó, J.; Bulló, M.; Babio, N.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Ibarrola-Jurado, N.; Basora, J.; Estruch, R.; Covas, M.I.; Corella, D.; Arós, F.; et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with the Mediterranean diet: Results of the PREDIMED-Reus nutrition intervention randomized trial. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrières, J. The French paradox: Lessons for other countries. Heart 2004, 90, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renaud, S.; de Lorgeril, M. Wine, alcohol, platelets, and the French paradox for coronary heart disease. Lancet 1992, 339, 1523–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Tucker, K.L. Coronary heart disease prevention: Nutrients, foods, and dietary patterns. Clin. Chim. Acta 2011, 412, 1493–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constant, J. Alcohol, ischemic heart disease, and the French paradox. Clin. Cardiol. 1997, 20, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseeb, S.; Alexander, B.; Baranchuk, A. Wine and Cardiovascular Health: A Comprehensive Review. Circulation 2017, 136, 1434–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseeb, S.; Alexander, B.; Santi, R.L.; Liprandi, A.S.; Baranchuk, A. What’s in wine? A clinician’s perspective. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 29, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Berge, A.F. How the ideology of low fat conquered america. J. Hist Med. Allied Sci. 2008, 63, 139–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keys, A. Diet and the epidemiology of coronary heart disease. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1957, 164, 1912–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szanto, S.; Yudkin, J. The effect of dietary sucrose on blood lipids, serum insulin, platelet adhesiveness and body weight in human volunteers. Postgrad. Med. J. 1969, 45, 602–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yudkin, J. Dietetic aspects of atherosclerosis. Angiology 1966, 17, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 8th ed. December 2015. Available online: https://health.gov/our-work/food-and-nutrition/2015-2020-dietary-guidelines/ (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- McGuire, S. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Nutrition and Your Health: Dietary Guidelines for Americans; Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1990.

- Austin, G.L.; Ogden, L.G.; Hill, J.O. Trends in carbohydrate, fat, and protein intakes and association with energy intake in normal-weight, overweight, and obese individuals: 1971–2006. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, L.S.; Li, L.; Ford, E.S.; Liu, S. Increased consumption of refined carbohydrates and the epidemic of type 2 diabetes in the United States: An ecologic assessment. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 774–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menke, A.; Casagrande, S.; Geiss, L.; Cowie, C.C. Prevalence of and Trends in Diabetes Among Adults in the United States, 1988–2012. JAMA 2015, 314, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin, E.J.; Virani, S.S.; Callaway, C.W.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Chang, A.R.; Cheng, S.; Chiuve, S.E.; Cushman, M.; Delling, F.N.; Deo, R.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018, 137, e67–e492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astrup, A.; Meinert Larsen, T.; Harper, A. Atkins and other low-carbohydrate diets: Hoax or an effective tool for weight loss? Lancet 2004, 364, 897–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollo, J. Account of Two Cases of Diabetes Mellitus, with Remarks. Ann. Med. Year 1797, 2, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, T.; Unwin, D.; Finucane, F. Low-Carbohydrate Diets in the Management of Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes: A Review from Clinicians Using the Approach in Practice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banting, W. Letter on corpulence, addressed to the public. 1869. Obes. Res. 1993, 1, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, W.C. Facts and ideas from anywhere. Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. Proc. 2009, 22, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M. Keto diets: Good, bad or ugly? J. Physiol. 2018, 596, 4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frigolet, M.E.; Ramos Barragán, V.E.; Tamez González, M. Low-carbohydrate diets: A matter of love or hate. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 58, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giugliano, D.; Maiorino, M.I.; Bellastella, G.; Esposito, K. More sugar? No, thank you! The elusive nature of low carbohydrate diets. Endocrine 2018, 61, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, S.B.; Das, S.K. One strike against low-carbohydrate diets. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 357–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Walczyk, T.; Wick, J.Y. The ketogenic diet: Making a comeback. Consult. Pharm. 2017, 32, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornish, D. Was Dr Atkins right? J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2004, 104, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evert, A.B.; Dennison, M.; Gardner, C.D.; Garvey, W.T.; Lau, K.H.K.; MacLeod, J.; Mitri, J.; Pereira, R.F.; Rawlings, K.; Robinson, S.; et al. Nutrition Therapy for Adults with Diabetes or Prediabetes: A Consensus Report. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, 731–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holesh, J.E.; Aslam, S.; Martin, A. Physiology, Carbohydrates. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Feinman, R.D.; Pogozelski, W.K.; Astrup, A.; Bernstein, R.K.; Fine, E.J.; Westman, E.C.; Accurso, A.; Frassetto, L.; Gower, B.A.; McFarlane, S.I.; et al. Dietary carbohydrate restriction as the first approach in diabetes management: Critical review and evidence base. Nutrition 2015, 31, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. A healthy diet sustainably produced. Int. Arch. Med. 2018, 7, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Masood, W.; Annamaraju, P.; Uppaluri, K.R. Ketogenic Diet. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499830/ (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Arnett, D.K.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Albert, M.A.; Buroker, A.B.; Goldberger, Z.D.; Hahn, E.J.; Himmelfarb, C.D.; Khera, A.; Lloyd-Jones, D.; McEvoy, J.W.; et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, e177–e232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, L.A.; Maurice, C.F.; Carmody, R.N.; Gootenberg, D.B.; Button, J.E.; Wolfe, B.E.; Ling, A.V.; Devlin, A.S.; Varma, Y.; Fischbach, M.; et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 2014, 505, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ley, R.E.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Klein, S.; Gordon, J.I. Microbial ecology: Human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature 2006, 444, 1022–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, J.; Li, Y.; Cai, Z.; Li, S.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, F.; Liang, S.; Zhang, W.; Guan, Y.; Shen, D.; et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature 2012, 490, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.H.W.; Kitai, T.; Hazen, S.L. Gut Microbiota in Cardiovascular Health and Disease. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 1183–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Klipfell, E.; Bennett, B.J.; Levison, B.S.; Dugar, B.; Feldstein, A.E.; Britt, D.B.; Fu, X.; Chung, Y.M.; Wu, Y.; et al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature 2011, 472, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chistiakov, D.A.; Bobryshev, Y.V.; Kozarov, E.; Sobenin, I.A.; Orekhov, A.N. Role of gut microbiota in the modulation of atherosclerosis-associated immune response. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, J.O.; Wyatt, H.R.; Peters, J.C. Energy balance and obesity. Circulation 2012, 126, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolls, B.J. The role of energy density in the overconsumption of fat. J. Nutr 2000, 130, 268S–271S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quatela, A.; Callister, R.; Patterson, A.; MacDonald-Wicks, L. The Energy Content and Composition of Meals Consumed after an Overnight Fast and Their Effects on Diet Induced Thermogenesis: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analyses and Meta-Regressions. Nutrients 2016, 8, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.A.; Velazquez, K.T.; Herbert, K.M. Influence of high-fat diet on gut microbiota: A driving force for chronic disease risk. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2015, 18, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, B.C.; Kanters, S.; Bandayrel, K.; Wu, P.; Naji, F.; Siemieniuk, R.A.; Ball, G.D.C.; Busse, J.W.; Thorlund, K.; Guyatt, G.; et al. Comparison of weight loss among named diet programs in overweight and obese adults: A meta-analysis. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2014, 312, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, C.D.; Trepanowski, J.F.; Del Gobbo, L.C.; Hauser, M.E.; Rigdon, J.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Desai, M.; King, A.C. Effect of Low-Fat vs Low-Carbohydrate Diet on 12-Month Weight Loss in Overweight Adults and the Association With Genotype Pattern or Insulin Secretion: The DIETFITS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018, 319, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meckling, K.A.; O’Sullivan, C.; Saari, D. Comparison of a low-fat diet to a low-carbohydrate diet on weight loss, body composition, and risk factors for diabetes and cardiovascular disease in free-living, overweight men and women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 2717–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, M.D.; Ryan, D.H.; Apovian, C.M.; Ard, J.D.; Comuzzie, A.G.; Donato, K.A.; Hu, F.B.; Hubbard, V.S.; Jakicic, J.M.; Kushner, R.F.; et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation 2014, 129, S102–S138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chawla, S.; Tessarolo Silva, F.; Amaral Medeiros, S.; Mekary, R.A.; Radenkovic, D. The Effect of Low-Fat and Low-Carbohydrate Diets on Weight Loss and Lipid Levels: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, F.; Korat, A.A.; Malik, V.; Hu, F.B. Metabolic Effects of Monounsaturated Fatty Acid-Enriched Diets Compared With Carbohydrate or Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid-Enriched Diets in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 1448–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasa, A.; Miranda, J.; Bulló, M.; Casas, R.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Larretxi, I.; Estruch, R.; Ruiz-Gutierrez, V.; Portillo, M.P. Comparative effect of two Mediterranean diets versus a low-fat diet on glycaemic control in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 68, 767–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itsiopoulos, C.; Brazionis, L.; Kaimakamis, M.; Cameron, M.; Best, J.D.; O’Dea, K.; Rowley, K. Can the Mediterranean diet lower HbA1c in type 2 diabetes? Results from a randomized cross-over study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2011, 21, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Look AHEAD Research Group; Pi-Sunyer, X.; Blackburn, G.; Brancati, F.L.; Bray, G.A.; Bright, R.; Clark, J.M.; Burtis, J.M.; Espeland, M.A.; Foreyt, Y.P.; et al. Reduction in weight and cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes: One-year results of the look AHEAD trial. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 1374–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunerova, L.; Smejkalova, V.; Potockova, J.; Andel, M. A comparison of the influence of a high-fat diet enriched in monounsaturated fatty acids and conventional diet on weight loss and metabolic parameters in obese non-diabetic and Type 2 diabetic patients. Diabet. Med. 2007, 24, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodama, S.; Saito, K.; Tanaka, S.; Maki, M.; Yachi, Y.; Sato, M.; Sugawara, A.; Totsuka, K.; Shimano, H.; Ohashi, Y.; et al. Influence of fat and carbohydrate proportions on the metabolic profile in patients with type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 959–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, M.L.; Dunbar, S.A.; Jaacks, L.M.; Karmally, W.; Mayer-Davis, E.J.; Wylie-Rosett, J.; Yancy, W.S. Macronutrients, food groups, and eating patterns in the management of diabetes: A systematic review of the literature, 2010. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, J.; Luscombe-Marsh, N.D.; Thompson, C.H.; Noakes, M.; Buckley, J.D.; Wittert, G.A.; Yancy, W.S.; Brinkworth, G.D. A very low-carbohydrate, low-saturated fat diet for type 2 diabetes management: A randomized trial. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 2909–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brehm, B.J.; Lattin, B.L.; Summer, S.S.; Boback, J.A.; Gilchrist, G.M.; Jandacek, R.J.; D’Alessio, D.A. One-year comparison of a high-monounsaturated fat diet with a high-carbohydrate diet in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katan, M.B.; Zock, P.L.; Mensink, R.P. Dietary oils, serum lipoproteins, and coronary heart disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1995, 61, 1368S–1373S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.B.; Stampfer, M.J.; Manson, J.E.; Rimm, E.; Colditz, G.A.; Rosner, B.A.; Hennekens, C.H.; Willett, W.C. Dietary fat intake and the risk of coronary heart disease in women. N. Engl. Med. 1997, 337, 1491–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwingshackl, L.; Chaimani, A.; Hoffmann, G.; Schwedhelm, C.; Boeing, H. A network meta-analysis on the comparative efficacy of different dietary approaches on glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 33, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.L.; Wang, Q.; Hong, Y.; Ojo, O.; Jiang, Q.; Hou, Y.Y.; Huang, Y.H.; Wang, X.H. The effect of low-carbohydrate diet on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutrients 2018, 10, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, N.J.; Tomuta, N.; Schechter, C.; Isasi, C.R.; Segal-Issaacson, C.J.; Stein, D.; Zonszein, J.; Wylie-Rosett, J. Comparative study of the effects of a 1-year dietary intervention of a low-carbohydrate diet versus a low-fat diet on weight and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 1147–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, N.; Vetter, M.L.; Moore, R.H.; Chittams, J.L.; Dalton-Bakes, C.V.; Dowd, M.; Williams-Smith, C.; Cardillo, S.; Wadden, T.A. Effects of a low-intensity intervention that prescribed a low-carbohydrate vs. a low-fat diet in obese, diabetic participants. Obesity 2010, 18, 1733–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guldbrand, H.; Dizdar, B.; Bunjaku, B.; Lindström, T.; Bachrach- Lindström, M.; Fredrikson, M.; Ostgren, C.J.; Nystrom, F.H. In type 2 diabetes, randomisation to advice to follow a low-carbohydrate diet transiently improves glycaemic control compared with advice to follow a low-fat diet producing a similar weight loss. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 2118–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, Z.; Guo, Y.; Hu, F.B.; Liu, L.; Qi, Q. Association of Low-Carbohydrate and Low-Fat Diets with Mortality Among US Adults. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, M.U.; O’Reilly, E.J.; Heitmann, B.L.; Pereira, M.A.; Bälter, K.; Fraser, G.E.; Goldbourt, U.; Hallmans, G.; Knekt, P.; Liu, S.; et al. Major types of dietary fat and risk of coronary heart disease: A pooled analysis of 11 cohort studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, K.; Hu, F.B.; Manson, J.E.; Stampfer, M.J.; Willett, W.C. Dietary fat intake and risk of coronary heart disease in women: 20 years of follow-up of the nurses’ health study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2005, 161, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Horn, L.; Aragaki, A.K.; Howard, B.V.; Allison, M.A.; Isasi, C.R.; Manson, J.E.; Neuhouser, M.L.; Mossavar-Rahmani, Y.; Thomson, C.A.; Vitolin, M.Z.; et al. Eating Pattern Response to a Low-Fat Diet Intervention and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Normotensive Women: The Women’s Health Initiative. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, nzaa021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Z.; Rehm, C.D.; Rogers, G.; Ruan, M.; Wang, D.D.; Hu, F.B.; Mozaffarian, D.; Zhang, F.F.; Bhupathiraju, S.N. Trends in Dietary Carbohydrate, Protein, and Fat Intake and Diet Quality Among US Adults, 1999–2016. JAMA 2019, 322, 1178–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Eilat-Adar, S.; Loria, C.; Goldbourt, U.; Howard, B.V.; Fabsitz, R.R.; Zephier, E.M.; Mattil, C.; Lee, E.T. Dietary fat intake and risk of coronary heart disease: The Strong Heart Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 84, 894–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leren, P. The Oslo diet-heart study. Eleven-year report. Circulation 1970, 42, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siri-Tarino, P.W.; Sun, Q.; Hu, F.B.; Krauss, R.M. Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating the association of saturated fat with cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamley, S. The effect of replacing saturated fat with mostly n-6 polyunsaturated fat on coronary heart disease: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Nutr. J. 2017, 16, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kromhout, D.; Bosschieter, E.B.; de Lezenne Coulander, C. The inverse relation between fish consumption and 20-year mortality from coronary heart disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1985, 312, 1205–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, R.; Castro-Barquero, S.; Estruch, R.; Sacanella, E. Nutrition and Cardiovascular Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascherio, A.; Rimm, E.B.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Spiegelman, D.; Stampfer, M.; Willett, W.C. Dietary fat and risk of coronary heart disease in men: Cohort follow up study in the United States. BMJ 1996, 313, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, M.F.; Burke, F.M.; Soffer, D.E. Review of Cardiometabolic Effects of Prescription Omega-3 Fatty Acids. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2017, 19, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spigoni, V.; Lombardi, C.; Cito, M.; Picconi, A. N-3 PUFA increase bioavailability and function of endothelial progenitor cells. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 1881–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Micha, R.; Wallace, S. Effects on coronary heart disease of increasing polyunsaturated fat in place of saturated fat: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, L.; Martin, N.; Abdelhamid, A.; Davey Smith, G. Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, CD011737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietinen, P.; Ascherio, A.; Korhonen, P.; Hartman, A.M.; Willett, W.C.; Albanes, D.; Virtamo, J. Intake of fatty acids and risk of coronary heart disease in a cohort of Finnish men. The Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1997, 145, 876–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leosdottir, M.; Nilsson, P.M.; Nilsson, J.A.; Berglund, G. Cardiovascular event risk in relation to dietary fat intake in middle-aged individuals: Data from The Malmö Diet and Cancer Study. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Prev. Rehabil. 2007, 14, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Covas, M.I.; Corella, D.; Arós, F.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Ruiz-Gutiérrez, V.; Fiol, M.; Lapetra, J. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet. N. Engl. Med. 2013, 368, 1279–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Covas, M.I.; Corella, D.; Arós, F.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Ruiz-Gutiérrez, V.; Fiol, M.; Lapetra, J. Retraction and Republication: Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2441–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam-Perrot, A.; Clifton, P.; Brouns, F. Low-carbohydrate diets: Nutritional and physiological aspects. Obes. Rev. 2006, 7, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westman, E.C.; Feinman, R.D.; Mavropoulos, J.C.; Vernon, M.C.; Volek, J.S.; Wortman, J.A.; Yancy, W.S.; Phinney, S.D. Low-carbohydrate nutrition and metabolism. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 86, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paoli, A.; Rubini, A.; Volek, J.S.; Grimaldi, K.A. Beyond weight loss: A review of the therapeutic uses of very-low-carbohydrate (ketogenic) diets. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 67, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebbeling, C.B.; Feldman, H.A.; Klein, G.L.; Wong, J.; Bielak, L.; Steltz, S.K.; Luoto, P.K.; Wolfe, R.R.; Wong, W.W.; Ludwig, D.S. Effects of a low carbohydrate diet on energy expenditure during weight loss maintenance: Randomized trial. BMJ 2018, 363, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, R.; Gilani, B.; Uppaluri, K.R. Low Carbohydrate Diet. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537084/ (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Gibson, A.A.; Seimon, R.V.; Lee, C.M.Y.; Ayre, J.; Franklin, J.; Markovic, T.P.; Caterson, I.D.; Sainsbury, A. Do ketogenic diets really suppress appetite? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leidy, H.J.; Clifton, P.M.; Astrup, A.; Wycherley, T.P.; Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S.; Luscombe-Marsh, N.D.; Woods, S.C.; Mattes, R.D. The role of protein in weight loss and maintenance. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 1320S–1329S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig, D.S. The glycemic index: Physiological mechanisms relating to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. JAMA 2002, 287, 2414–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seid, H.; Rosenbaum, M. Low carbohydrate and low-fat diets: What we don’t know and why we should know it. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehm, B.J.; Seeley, R.J.; Daniels, S.R.; D’Alessio, D.A. A randomized trial comparing a very low carbohydrate diet and a calorie-restricted low fat diet on body weight and cardiovascular risk factors in healthy women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 88, 1617–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samaha, F.F.; Iqbal, N.; Seshadri, P.; Chicano, K.L.; Daily, D.A.; McGrory, J.; Williams, T.; Williams, M.; Gracely, E.J.; Stern, L. A low-carbohydrate as compared with a low-fat diet in severe obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 2074–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yancy, W.S., Jr.; Olsen, M.K.; Guyton, J.R.; Bakst, R.P.; Westman, E.C. A low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet versus a low-fat diet to treat obesity and hyperlipidemia: A randomized, controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2004, 140, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brehm, B.J.; Spang, S.E.; Lattin, B.L.; Seeley, R.J.; Daniels, S.R.; D’Alessio, D.A. The role of energy expenditure in the differential weight loss in obese women on low-fat and low-carbohydrate diets. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 1475–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sackner-Bernstein, J.; Kanter, D.; Kaul, S. Dietary intervention for overweight and obese adults: Comparison of low- carbohydrate and low-fat diets. a meta- analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, Y.; Fukuda, T.; Oyabu, C.; Tanaka, M.; Asano, M.; Yamazaki, M.; Fukui, M. Impact of low-carbohydrate diet on body composition: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Obes. Rev. 2016, 17, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, N.B.; De Melo, I.S.V.; De Oliveira, S.L.; Da Rocha Ataide, T. Very-low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet v. low-fat diet for long-term weight loss: A meta-analysis of Randomised controlled trials. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 110, 1178–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hession, M.; Rolland, C.; Kulkarni, U.; Wise, A.; Broom, J. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of low-carbohydrate vs. low-fat/low-calorie diets in the management of obesity and its comorbidities. Obes. Rev. 2009, 10, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobias, D.K.; Chen, M.; Manson, J.A.E.; Ludwig, D.S.; Willett, W.; Hu, F.B. Effect of low-fat diet interventions versus other diet interventions on long-term weight change in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015, 3, 968–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, B.; Raynor, H.A.; Tepper, B.J. PROP Nontaster Women Lose More Weight Following a Low-Carbohydrate Versus a Low-Fat Diet in a Randomized Controlled Trial. Obesity 2017, 25, 1682–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, G.D.; Wyatt, H.R.; Hill, J.O.; Makris, A.P.; Rosenbaum, D.L.; Brill, C.; Stein, R.I.; Mohammed, B.S.; Miller, B.; Rader, D.J.; et al. Weight and metabolic outcomes after 2 years on a low-carbohydrate versus low-fat diet: A randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010, 153, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkpatrick, C.F.; Bolick, J.P.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Sikand, G.; Aspry, K.E.; Soffer, D.E.; Willard, K.E.; Maki, K.C. Review of current evidence and clinical recommendations on the effects of low-carbohydrate and very-low-carbohydrate (including ketogenic) diets for the management of body weight and other cardiometabolic risk factors: A scientific statement from the Nat. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2019, 13, 689–711.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosentino, F.; Grant, P.J.; Aboyans, V.; Bailey, C.J.; Ceriello, A.; Delgado, V.; Federici, M.; Filippatos, G.; Grobbee, D.E.; Hansen, T.B.; et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 255–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, J.R., Jr. A brief history of the development of diabetes medications. Diabetes Spectr. 2014, 27, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westman, E.C.; Yancy, W.S.; Humphreys, M. Dietary treatment of diabetes mellitus in the pre-insulin era (1914–1922). Perspect. Biol. Med. 2006, 49, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, F.M. Studies concerning diabetes. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1914, 63, 939–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joslin, E.P. The Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1916, 6, 673–684. [Google Scholar]

- Turton, J.; Brinkworth, G.D.; Field, R.; Parker, H.; Rooney, K. An evidence-based approach to developing low-carbohydrate diets for type 2 diabetes management: A systematic review of interventions and methods. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2019, 21, 2513–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanri, A.; Mizoue, T.; Kurotani, K.; Goto, A.; Oba, S.; Noda, M.; Sawada, N.; Tsugane, S.; Song, Y. Low-carbohydrate diet and type 2 diabetes risk in Japanese men and women: The Japan Public Health Center-Based Prospective Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArdle, P.D.; Greenfield, S.M.; Rilstone, S.K.; Narendran, P.; Haque, M.S.; Gill, P.S. Carbohydrate restriction for glycaemic control in Type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet. Med. 2019, 36, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huntriss, R.; Campbell, M.; Bedwell, C. The interpretation and effect of a low-carbohydrate diet in the management of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, S.; Kabeya, Y.; Noto, H. Dietary approaches for Japanese patients with diabetes: A systematic review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westman, E.C.; Tondt, J.; Maguire, E.; Yancy, W.S. Implementing a low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet to manage type 2 diabetes mellitus. Expert Rev. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 13, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snorgaard, O.; Poulsen, G.M.; Andersen, H.K.; Astrup, A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary carbohydrate restriction in patients with type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2017, 5, e000354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halton, T.L.; Willett, W.C.; Liu, S.; Manson, J.E.; Albert, C.M.; Rexrode, K.; Hu, F.B. Low-Carbohydrate-Diet Score and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in Women. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 1991–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhuang, X.; Lin, X.; Zhong, X.; Zhou, H.; Sun, X.; Xiong, Z.; Huang, Y.; Fan, Y.; Guo, Y.; et al. Low-Carbohydrate Diets and Risk of Incident Atrial Fibrillation: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidelmann, S.B.; Claggett, B.; Cheng, S.; Henglin, M.; Shah, A.; Steffen, M.L.; Folsom, A.R.; Rimm, E.B.; Willett, W.C.; Solomon, S.D. Dietary carbohydrate intake and mortality: A prospective cohort study and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Heal. 2018, 3, e419–e428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noto, H.; Goto, A.; Tsujimoto, T.; Noda, M. Low-Carbohydrate Diets and All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. PLoS ONE 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.; Bazzano, L.A. The low-carbohydrate diet and cardiovascular risk factors: Evidence from epidemiologic studies. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2014, 24, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagiou, P.; Sandin, S.; Lof, M.; Trichopoulos, D.; Adami, H.O.; Weiderpass, E. Low carbohydrate-high protein diet and incidence of cardiovascular diseases in Swedish women: Prospective cohort study. BMJ 2012, 345, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retterstøl, K.; Svendsen, M.; Narverud, I.; Holven, K.B. Effect of low carbohydrate high fat diet on LDL cholesterol and gene expression in normal-weight, young adults: A randomized controlled study. Atherosclerosis 2018, 279, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durrer, C.; Lewis, N.; Wan, Z.; Ainslie, P.N.; Jenkins, N.T.; Little, J.P. Short-term low-carbohydrate high-fat diet in healthy young males renders the endothelium susceptible to hyperglycemia-induced damage, an exploratory analysis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, T.; Guo, M.; Zhang, P.; Sun, G.; Chen, B. The effects of low-carbohydrate diets on cardiovascular risk factors: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0225348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Y.; Bai, H.; Wang, S.; Li, Z.; Wang, Q.; Chen, L. Efficacy of low carbohydrate diet for type 2 diabetes mellitus management: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2017, 131, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorber, D. Importance of cardiovascular disease risk management in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2014, 7, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unwin, D.J.; Tobin, S.D.; Murray, S.W.; Delon, C.; Brady, A.J. Substantial and sustained improvements in blood pressure, weight and lipid profiles from a carbohydrate restricted diet: An observational study of insulin resistant patients in primary care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdy, O.; Tasabehji, M.W.; Elseaidy, T.; Tomah, S.; Ashrafzadeh, S.; Mottalib, A. Fat Versus Carbohydrate-Based Energy-Restricted Diets for Weight Loss in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan, M.; Mente, A.; Zhang, X.; Swaminathan, S.; Li, W.; Mohan, V.; Iqbal, R.; Kumar, R.; Wentzel- Viljoen, E.; Rosengren, A.; et al. Associations of fats and carbohydrate intake with cardiovascular disease and mortality in 18 countries from five continents (PURE): A prospective cohort study. Lancet 2017, 390, 2050–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, F.K.; Gray, S.R.; Welsh, P.; Petermann- Rocha, F.; Foster, H.; Waddell, H.; Anderson, J.; Lyall, D.; Sattar, N.; Gill, J.M.R.; et al. Associations of fat and carbohydrate intake with cardiovascular disease and mortality: Prospective cohort study of UK Biobank participants. BMJ 2020, 368, m688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieri, S.; Agnoli, C.; Grioni, S.; Weiderpass, E.; Mattiello, A.; Sluijs, I.; Sanchez, M.J.; Jakobsen, M.U.; Sweeting, M.; van der Schouw, Y.T.; et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and risk of coronary heart disease: A pan-European cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srour, B.; Fezeu, L.K.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Allès, B.; Méjean, C.; Andrianasolo, M.R.; Chazelas, E.; Deschasaux, M.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; et al. Ultra-processed food intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: Prospective cohort study (NutriNet-Santé). BMJ 2019, 365, l1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, A.; Borgo, F.; Lassandro, C.; Verduci, E.; Morace, G.; Borghi, E.; Berry, D. Pediatric obesity is associated with an altered gut microbiota and discordant shifts in Firmicutes populations. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 19, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsson, F.H.; Tremaroli, V.; Nookaew, I.; Bergström, G.; Behre, C.J.; Fagerberg, B.; Nielsen, J.; Bäckhed, F. Gut metagenome in European women with normal, impaired and diabetic glucose control. Nature 2013, 498, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, N.; Vogensen, F.K.; van den Berg, F.W.; Nielsen, D.S.; Andreasen, A.S.; Pedersen, B.K.; Al- Soud, W.A.; Sørensen, S.J.; Hansen, L.H.; Jakobsen, M. Gut microbiota in human adults with type 2 diabetes differs from non-diabetic adults. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.V.; Frassetto, A.; Kowalik, E.J.J.; Nawrocki, A.R.; Lu, M.M.; Kosinski, J.R.; Hubert, J.A.; Szeto, D.; Yao, X.; Forrest, G.; et al. Butyrate and propionate protect against diet-induced obesity and regulate gut hormones via free fatty acid receptor 3-independent mechanisms. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhassan, S.; Kim, S.; Bersamin, A.; King, A.C.; Gardner, C.D. Dietary adherence and weight loss success among overweight women: Results from the A to Z weight loss study. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 985–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grembi, J.A.; Nguyen, L.H.; Haggerty, T.D.; Gardner, C.D.; Holmes, S.P.; Parsonnet, J. Gut microbiota plasticity is correlated with sustained weight loss on a low-carb or low-fat dietary intervention. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, Y.; Wang, F.; Yuan, J.; Lie, J.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Wang, R.; Tang, J.; Huang, T.; et al. Effects of dietary fat on gut microbiota and faecal metabolites, and their relationship with cardiometabolic risk factors: A 6-month randomised controlled-feeding trial. Gut 2019, 68, 1417–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnenburg, E.D.; Smits, S.A.; Tikhonov, M.; Higginbottom, S.K.; Wingreen, N.S.; Sonnenburg, J.L. Diet-induced extinctions in the gut microbiota compound over generations. Nature 2016, 529, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazemian, N.; Mahmoudi, M.; Halperin, F.; Wu, J.C.; Pakpour, S. Gut microbiota and cardiovascular disease: Opportunities and challenges. Microbiome 2020, 8, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeth, R.A.; Wang, Z.; Levison, B.S.; Buffa, J.A.; Org, E.; Sheehy, B.T.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, L.; et al. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of L-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiattarella, G.G.; Sannino, A.; Toscano, E.; Giugliano, G.; Gargiulo, G.; Franzone, A.; Trimarco, B.; Esposito, G.; Perrino, C. Gut microbe-generated metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide as cardiovascular risk biomarker: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 2948–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laudisi, F.; Stolfi, C.; Monteleone, G. Impact of Food Additives on Gut Homeostasis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinöcker, M.K.; Lindseth, I.A. The western diet–microbiome-host interaction and its role in metabolic disease. Nutrients 2018, 10, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors (Year) Study Type | Studies/Participants (N) Average Duration of Follow-Up | Population | Diet Type Compared | Findings (Weight Loss/Hunger) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meckling et al. (2004) RCT [63] | 1/31 10 weeks | Overweight and obese adult men and women | LFD vs. LCD | No significant differences in body weight between the studied groups of patients |

| Johnston et al. (2014) [61] Meta-analysis, RCT | 48/7286 6 and 12 months | Overweight and obese (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) adults without co-morbidities. | LCD vs. LFD vs. no special diet | Weight loss observed on LCD was: 8.73 kg (95% CI: 7.27 to 10.20 kg) after 6 months of follow-up and 7.25 kg (95% CI: 5.33 to 9.25 kg) after 12 months. Weight loss on LFD was 7.99 kg (95% CI, 6.01 to 9.92 kg) after 6 months of follow-up and 7.27 kg (95% CI, 5.26 to 9.34 kg) after 12 months. There were no significant differences between diets. |

| Gardner CD et al. (2018) [62] RCT, DIETFITS | 1/609 1 year | Adults without diabetes with a BMI 28–40 | LFD vs. LCD | There was no significant difference in weight loss. |

| Chawla et al. (2020) [65] Systematic review and meta-analysis of RCT | 38/6499 6 and 12 months | Healthy adult, BMI 22 and 43.6 kg/m2 | LCD vs. LFD | LCD at 6–12 months was favored for average weight change—polled analyses—mean difference −1.30 kg; 95% CI −2.02 to −0.57 |

| Authors (Year) Study Type | Studies/Participants (N) Average Duration of Follow-Up (Years) | Population | Diet Type Compared | Findings: T2DM Control (HbA1c/HOMA-IR/FPG/Need for Antidiabetic Drugs/Glycemic Variability) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brunerova et al. (2007) [70] RCT | 1/58 3 months | T2DM and obese non-T2DM adults | High-fat diet enriched with MUFA vs. conventional diet | Decrease in HbA1c from 7.3 ± 0.4% to 6.6 ± 0.3% (p < 0.01) on high-fat diet enriched with MUFA vs. from 6.9 ± 0.6% to 6.5 ± 0.5% (p > 0.01) on conventional diet |

| Davis et al. (2009) [79] RTC | 1/105 1 year | Overweight adults with T2DM | LCD vs. LFD | There was no significant change in HbA1C in either group. |

| Brehm et al. (2009) [74] Cohort study | 1/1124 1 year | Overweight and obese T2DM adults | High-quality high-MUFA diet vs. HCD | Both diets were equally effective; no significant differences were shown |

| Iqbal et al. (2010) [80] RTC | 1/144 2 years | Obese adults with T2DM | LCD vs. LFD | At month 6, LCD was associated with a clinically significant reduction in HbA1c of −0.5% (compared to −0.1% on LFD), but this was not sustained over time |

| Itsiopoulos et al. (2011) [68] RCT | 1/27 24 weeks | Adults with TDM2. | MED vs. no diet | HbA1c decreased from 7.1% (95% CI: 6.5–7.7) to 6.8% (95% CI: 6.3–7.3) (p = 0.012) on MED diet |

| Guldbrand et al. (2012) [81] Prospective randomized parallel trial | 1/61 2 years | Adults with TDM2 | LFD vs. LCD | HbA1c LCD at 6 months −4.8 ± 8.3 mmol/mol, p = 0.004, at 12 months −2.2 ± 7.7 mmol/mol, p = 0.12; LFD at 6 months −0.9 ± 8.8 mmol/mol, p = 0.56) Insulin doses were reduced in the LCD group (0 months, LCD 42 ± 65 E, LFD 39 ± 51 E; 6 months, LCD 30 ± 47 E, LFD 38 ± 48 E; p = 0.046 for between-group change) |

| Lasa et al. (2014) [67] Parallel trial | 1/177 1 year | Adults free of cardiovascular disease but with T2DM; the participants followed oral anti-diabetic treatments. Participants of the PREDIMED | MED with olive oil vs. MED with nuts vs. LFD | The adiponectin/HOMA-IR (A/HOMA-IR) ratio was significantly increased in the MED with olive oil eatery group and the trend was observed in the MED with nut eatery group (p = 0.069) and the LFD group (p = 0.061). |

| Qian et al. (2016) [66] Systematic review and meta-analysis of RCT | 24/1460 Up to 3 years | Adults with T2DM | High-MUFA diet vs. HCD | Reductions in fasting plasma glucose: WMD−0,57 mmol/l [95%CI−0.76,−0.39] on High-MUFA diet compared to HCD |

| Schwingshackl et al. (2017) [77] Network Meta-analysis, Randomized trials | 56/4937 3–48 months | Adults with T2DM | LCD vs. LFD | LCD caused significantly greater reduction in HbA1c than LFD: (95% CI) −0.35 (−0.56/−0.14)% |

| Wang et al. (2018) [78] Prospective, Single-blind randomized controlled trial | 1/56 3 months | Chinese T2DM adults | LCD vs. LFD | LCD caused significantly greater reduction in HbA1c than LFD: (95% CI) −0.63% vs. −0.31%, p < 0.05. |

| Authors (Year) Study Type | Studies/Participants (N) Average Duration of Follow-Up (Years) | Population | Diet Type Compared | Findings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVD Mortality | CHD Risk | Lipids/Blood Pressure | AF | ||||

| Ascherio et al. (1996) [93] Prospective | 1/43757 6 years | Health professional, adults free of diagnosed CVD or T2DM | Diet with high saturated fat vs. diet with low saturated fat intake | - | There was no direct association between reduced saturated fat intake and reduction in CHD risk. | - | - |

| Pietinen et al. (1997) [98] Prospective | 1/21930 6 years | Adult male smokers who were initially free of diagnosed CVD | Low trans fatty acid vs. high trans fatty acid intake | - | RR of coronary death = 1.39 (95% Cl 1.09–1.78) (p = 0.004) for the highest vs. lowest quintile of trans fatty acid intake. | - | - |

| Oh et al. (2005) [84] Observations, prospective epidemiologic studies | 1/78778 20 years | US adult women initially free of CVD and T2DM | PUFA vs. trans fat intake | - | PUFA intake was inversely associated with CHD risk (multivariate relative risk (RR) for the highest vs. the lowest quintile = 0.75, 95% CI: 0.60–0.92; p trend = 0.004), whereas trans fat intake was associated with an elevated risk of CHD (RR = 1.33, 95% CI: 1.07, −1.66; p trend = 0.01). | - | - |

| Xu et al. (2006) [87] Prospective | 1/2938 7 years | Native American adults free of CHD | High saturated fatty acids and MUFA vs. low saturated fatty acids and MUFA intake | Participants aged 47–59 years in the highest quartile of intake of total fat, saturated fatty acids, or MUFA had higher CHD mortality than did those in the lowest quartile (hazard ratio (95% CI): 3.57 (1.21, −10.49), 5.17 (1.64–16.36), and 3.43 (1.17–10.04)). | - | - | - |

| Leosdottir et al. (2007) [99] Prospective | 1/28098 8 years | Middle-aged individuals with no history of CVD | LFD vs. diet with high intake of unsaturated fats | - | There was no association between the risk of CHD and any of the diets. | - | - |

| Mozaffarian et al., (2010) [96] Meta-analysis, RCT | 8/13614 - | Adults who increased PUFA for at least 1 year without major concomitant interventions | PUFA vs. saturated fat intake | - | The overall pooled risk reduction was 19% (RR = 0.81, 95% CI 0.70–0.95, p = 0.008), corresponding to 10% reduced CHD risk (RR = 0.90, 95% CI = 0.83–0.97) for each 5% energy of increased PUFA. | - | - |

| Hooper et al. (2015) [97] Meta-analysis, RCT | 15/58509 - | Adults with or without CVD | Saturated fats vs. PUFA intake | Lowering dietary saturated fat reduced the CVD mortality (RR 0.95; 95% CI 0.80 to 1.12). | Lowering dietary saturated fat reduced the CHD risk by 17% (risk ratio (RR) 0.83; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.72 to 0.96). | - | - |

| Van Horn et al. (2020) [85] Intervention study “Women’s Health Initiative Dietary Modification” | 1/10371 1 year | Adult women without CVD or hypertension | LFD vs. HFD | - | Total fat reduction replaced with increased carbohydrate and some protein, especially plant-based protein, was related to lower CHD risk (in the upper quartile of plant protein intake having a CHD HR of 0.39 (95% CI: 0.22, 0.71), compared with 0.92 (95% CI: 0.57, 1.48) for those in the lower quartile). | - | - |

| Authors (Year) Study Type | Studies/Participants (N) Average Duration of Follow-Up | Population | Diet Type Compared | Findings (Weight Loss/Hunger) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samaha et al. (2003) [112] RCT | 1/132 6 months | Obese adults with T2DM or metabolic syndrome | LCD vs. LFD | LCD caused significantly greater weight loss than LFD: −5.8 ± 8.6 kg vs. −1.9 ± 4.2 kg; p = 0.002. |

| Yancy et al. (2004) [113] RCT | 1/120 24 weeks | Obese adults with lipid disorders and no serious medical condition | LCD vs. LFD | LCD caused significantly greater weight loss than LFD: −12.9% vs. −6.7%; p < 0.001. |

| Brehm et al. (2005) [114] RCT | 1/50 4 months | Obese adult women | LCD vs. LFD | LCD caused significantly greater weight loss than LFD: 9.79 ± 0.71 kg vs. 6.14 ± 0.91 kg; p < 0.05; and body fat loss: 6.20 ± 0.67 kg vs. 3.23 ± 0.67 kg; p < 0.05. |

| Foster et al. (2010) [121] Randomized parallel-group trial. | 1/307 2 years | Obese adults | LCD vs. LFD | There was no statistically significant difference in weight loss. |

| Bueno et al. (2013) [117] Meta-analysis, RCT | 13/1415 At least 12 months | Overweight and obese adults with no restrictions based on sex, race or co-morbidities. | VLCKD vs. LFD | VLCKD caused significantly greater weight loss than LFD: −0.91 (95% CI: −1.65, −0.17) kg. |

| Gibson et al. (2015) [107] Systematic review, Meta-analysis, Randomized and non-randomized trials | 12/967 4–12 weeks | Overweight and obese adults without co-morbidities | VLCKD measured in visual analogue scales. No comparison to other diets | VLCKD caused significant decrease in hunger by 5.5 mm (95% CI: −8.5, −2.5) and desire to eat decreased significantly by 8.9 mm (95% CI: −16.0, −1.8). |

| Sackner-Bernstein (2015) et al. [115] Meta-analysis, RCT | 17/1797 8 weeks to 24 months | Overweight and obese adults with and without co-morbidities. | LCD vs. LFD | LCD caused significantly greater weight loss than LFD: (95% CI) −2.0 (−3.1, −0.9) kg. |

| Hashimoto et al. (2016) [116] Meta-analysis, RCT | 14/1416 2–24 months | Obese adults with or without co-morbidities | LCD vs. control diet | LCD was associated with significantly greater weight loss: (95% CI) −0.7 (−1.07, −0.33) kg; and significantly greater decrease in fat mass: −0.77 (−1.55, −0.32) kg. |

| Authors (Year) Study Type | Studies/Participants (N) Average Duration of Follow-Up | Population | Diet Type Compared | Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2DM Risk Incidence | T2DM Control | ||||

| Tay et al. (2014) [73] RCT | 1/115 2 years | Overweight and obese adults with T2DM | LCD vs. HCD | - | Reduction in the need for antidiabetic drugs: −0.5 ± 0.5 on LCD vs. −0.2 ± 0.5 on HCD; p ≤ 0.03; reduction in HbA1c: −2.6 ± 1.0% (−28.4 ± 10.9 mmol/mol) on LCD vs. −1.9 ± 1.2% (−20.8 ± 13.1 mmol/mol) on HCD; p = 0.002. |

| Nanri (2015) [129] Prospective study | 1/64 674 5 years | Japanese adults without previous history of T2DM | LCD vs. other diets | LCD caused decreased risk of T2DM incidence in women (p < 0.001). | - |

| Huntriss et al. (2016) [131] Systematic review, Meta-analysis, RCTs | 18/2204 12 weeks to 4 years | Adults with T2DM | LCD vs. other diets | - | LCD caused significantly greater reduction in HbA1c than other diets: (95% CI) −0.28 (−0.53, −0.02)% (p = 0.03). |

| Snorgaard et al. (2017) [134] Systemic review and meta-analysis | 10/1376 1 year | Adults with T2DM | LCD vs. HCD | - | LCD caused significantly greater reduction in HbA1c than HCD: 0.34% (3.7 mmol/mol) compared to HCD: (95% CI) 0.06% (0.7 mmol/mol), 0.63% (6.9 mmol/mol). |

| McArdle et al. (2018) [130] Systematic review, Meta-analysis, RCTs | 25/2132 3 months to 4 years | Adults with T2DM | LCD vs VLCD | - | LCD had no effect on HbA1c: (95% CI) −0.09 (−0.27, 0.08)% (p = 0.30). VLCD lead to significant HbA1c reduction: (95% CI) −0.49 (−0.75, −0.23)% (p < 0.001). |

| Yamada et al. (2018) [132] Systematic review | 3/105 6 months | Japanese T2DM adults | LCD vs. calorie-restricted diet | - | LCD caused significantly greater reduction in HbA1c than calorie-restricted diet: 7.0 ± 0.7% vs. 7.5 ± 1.0%; p = 0.03. |

| Turton et al. (2019) [128] Meta-analysis, randomized and non-randomized controlled trials, single-arm intervention studies, retrospective case series analyses, case reports | 41/2135 14 days to 24 months | Adults with T2DM | LCD and VLCD, No comparison to other diets | - | All but one of the 41 included LCD interventions were classified as effective in T2DM and none was found to be unsafe. |

| Authors (Year) Study Type | Studies/Participants (N) Average Duration of Follow-Up | Population | Diet Type Compared | Findings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVD Mortality | CHD Risk | Lipids/Blood Pressure | AF | ||||

| Halton et al. (2006) [135] Prospective, Cohort | 1/82 802 20 years | Adult female registered nurses from United States | LCD vs. HCD | - | LCD relative risk (95% CI) for CHD: 0.94 (0.76–1.18, p = 0.19). | - | - |

| Lagiou et al. (2012) [140] Prospective, Cohort | 1/43 396 15.7 years | Random population sample of Swedish adult women | LCD vs. HCD | - | LCD rate ratio (95% CI) for increased CVD incidence: 1.04 (1–1.08). | - | - |

| Noto et al. (2013) [138] Systematic review, Meta-analysis, Cohort | 4/272 216 At least 1 year | Adults with or without comorbidities | LCD vs. HCD | LCD risk ratio (95% CI) for all-cause mortality: 1.31 (1.07–1.59) LCD risk ratio for CVD mortality and incidence was not statistically significant. | - | - | - |

| Seidelmann et al. (2018) [137] Prospective, cohort | 1/15 428 25 years | Adults from United States who did not report extreme caloric intake | LCD vs. HCD | Mortality risk (95% CI) for LCD: 1.2 (1.09–1.32). Mortality risk (95% CI) for HCD: 1.23 (1.11–1.36). | - | - | - |

| Zhang et al. (2019) [136] Prospective, cohort | 1/13 385 22.4 years | Adults from United States | LCD vs. HCD | - | - | - | Increased risk of AF incident (95% CI) for LCD: HR = 0.82 (0.72-0.94) for AF occurrence related to a 9.4% increase in carbohydrate intake. |

| Dong et al. (2020) [143] Systematic review, meta-analysis, RCT | 12/1 640 at least 3 months | Healthy adults from the USA, Australia, UK, Israel and China. | LCD vs. HCD | - | LCD caused significant changes in: Decrease in triglyceride levels: −0.15 mmol/L (95% CI: −0.23, −0.07); Decrease in systolic blood pressure: −1.41 mmHg (95% CI: —2.26, −0.56); Decrease in diastolic blood pressure: −1.71 mmHg (95% CI: —2.36, −1.06); Increase in plasma HDL-C: 0.1 mmol/L (95% CI: 0.08, 0.12); Decrease in serum total cholesterol: 0.13 mmol/L (95% CI: 0.08, 0.19). | - | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nabrdalik, K.; Krzyżak, K.; Hajzler, W.; Drożdż, K.; Kwiendacz, H.; Gumprecht, J.; Lip, G.Y.H. Fat, Sugar or Gut Microbiota in Reducing Cardiometabolic Risk: Does Diet Type Really Matter? Nutrients 2021, 13, 639. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020639

Nabrdalik K, Krzyżak K, Hajzler W, Drożdż K, Kwiendacz H, Gumprecht J, Lip GYH. Fat, Sugar or Gut Microbiota in Reducing Cardiometabolic Risk: Does Diet Type Really Matter? Nutrients. 2021; 13(2):639. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020639

Chicago/Turabian StyleNabrdalik, Katarzyna, Katarzyna Krzyżak, Weronika Hajzler, Karolina Drożdż, Hanna Kwiendacz, Janusz Gumprecht, and Gregory Y. H. Lip. 2021. "Fat, Sugar or Gut Microbiota in Reducing Cardiometabolic Risk: Does Diet Type Really Matter?" Nutrients 13, no. 2: 639. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020639

APA StyleNabrdalik, K., Krzyżak, K., Hajzler, W., Drożdż, K., Kwiendacz, H., Gumprecht, J., & Lip, G. Y. H. (2021). Fat, Sugar or Gut Microbiota in Reducing Cardiometabolic Risk: Does Diet Type Really Matter? Nutrients, 13(2), 639. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020639