Calcium Supplements and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Search

2.2. Study Selection and Eligibility

2.3. Assessment of the Risk of Bias

2.4. Main and Subgroup Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

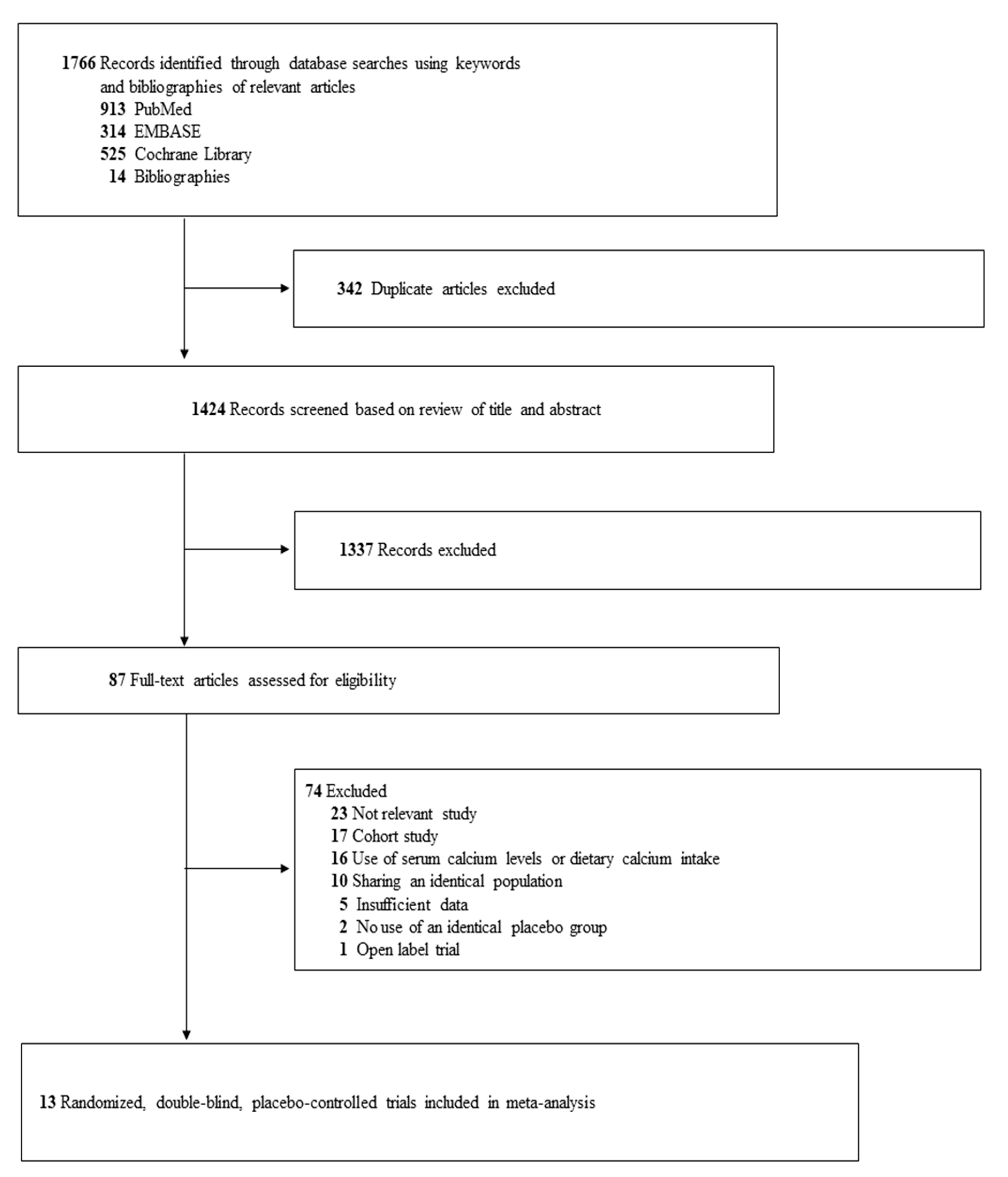

3.1. Identification of Relevant Studies

3.2. General Characteristics of Trials

3.3. Association between the Use of Calcium Supplements and Risk of CVD, CHD, and Cerebrovascular Disease

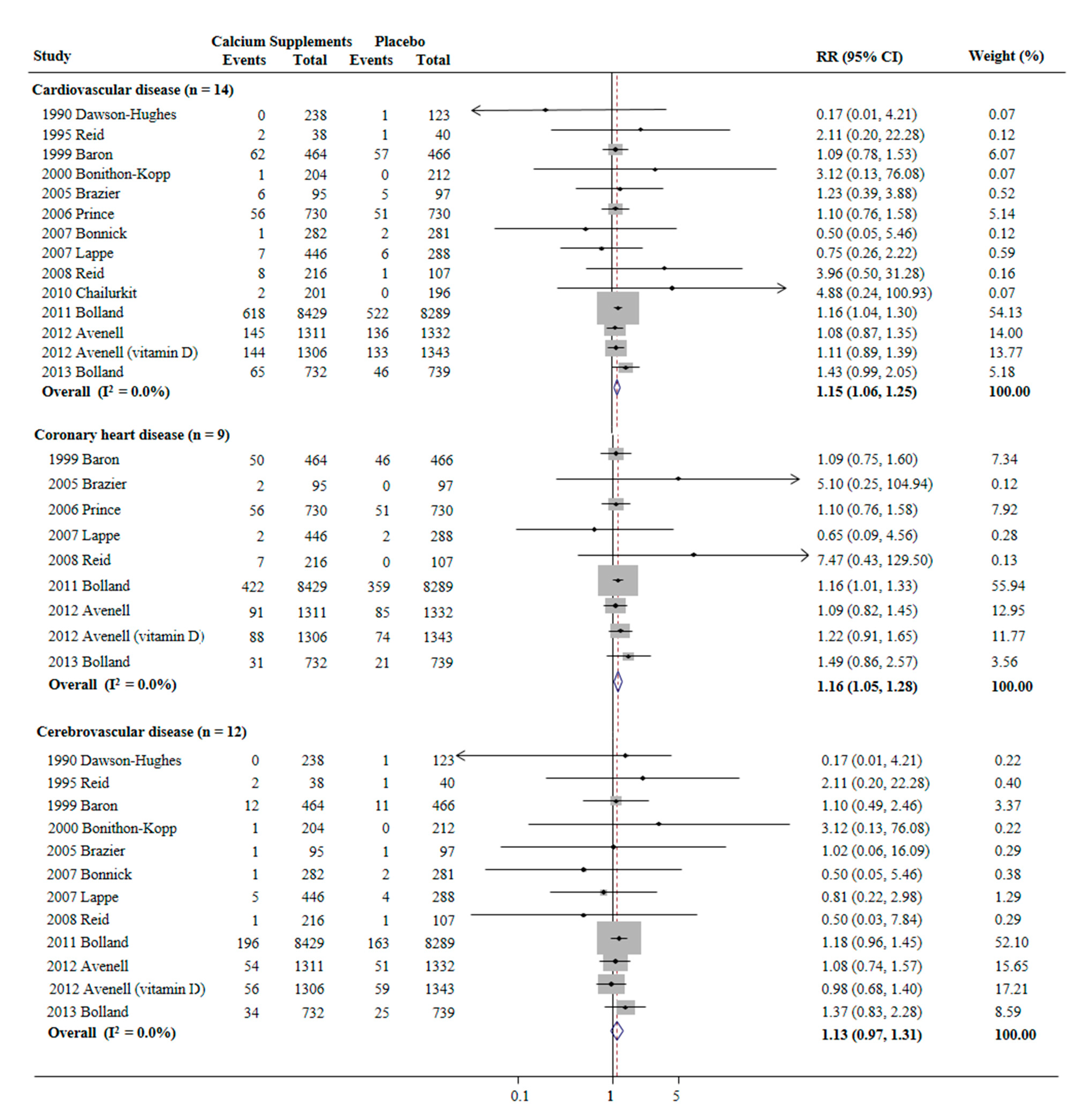

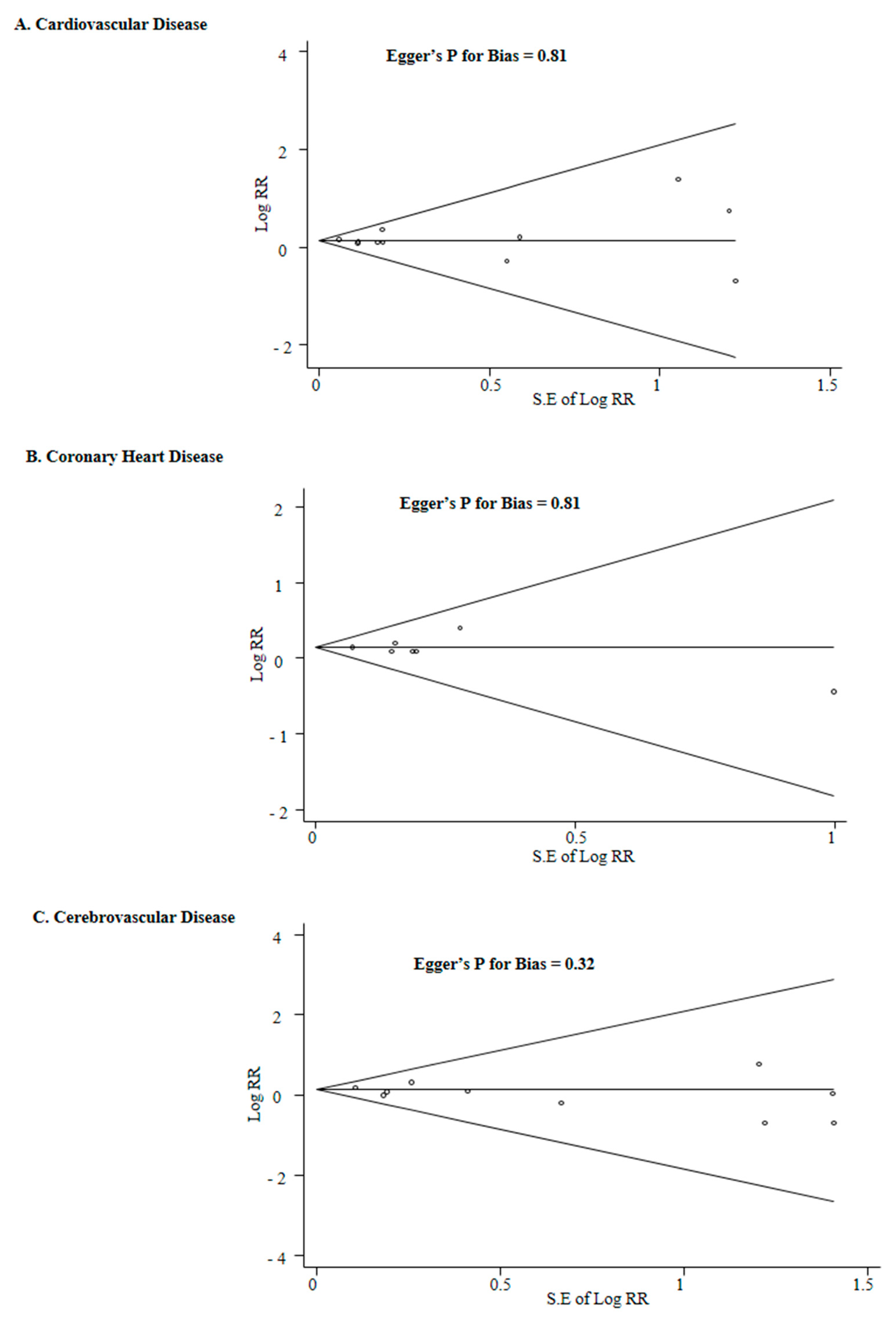

3.4. Subgroup Meta-Analysis

3.5. Differences among the Previous Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses and the Current Study

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cosman, F.; de Beur, S.J.; LeBoff, M.S. Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treat-ment of Osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int. 2014, 25, 2359–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho, P.M.; Petak, S.M.; Binkley, N. American association of clinical endocrinologists and american college of endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of post-menopausal osteoporosis. Endocr. Pract. 2016, 22 (Suppl. 4), 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compston, J.E.; The National Osteoporosis Guideline Group (NOGG); Cooper, A.; Cooper, C.; Gittoes, N.; Gregson, C.L.; Harvey, N.C.; Hope, S.; Kanis, J.A.; McCloskey, E. UK clinical guideline for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Arch. Osteoporos. 2017, 12, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolland, M.J.; Avenell, A.; Baron, J.A. Effect of calcium supplements on risk of myo-cardial infarction and cardiovascular events: Meta-analysis. BMJ 2010, 341, c3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolland, M.J.; Grey, A.; Avenell, A. Calcium supplements with or without vitamin D and risk of cardiovascular events: Reanalysis of the Women’s Health Initiative lim-ited access dataset and meta-analysis. BMJ 2011, 342, d2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.R.; Radavelli-Bagatini, S.; Rejnmark, L. The effects of calcium supplemen-tation on verified coronary heart disease hospitalization and death in postmenopausal women: A collaborative meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2015, 30, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, B.E.; Lewis, J.R.; Daly, R.M. The calcium scare—What would Austin Brad-ford Hill have thought? Osteoporos. Int. 2011, 22, 3073–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolland, M.J.; Grey, A.; Reid, I.R. Re: The calcium scare: What would Austin Bradford Hill have thought? Osteoporos. Int. 2011, 22, 3079–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolland, M.J.; Grey, A.; Avenell, A.; Reid, I.R. Calcium supplements increase risk of myo-cardial infarction. J. Bone. Miner. Res. 2015, 30, 389–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.; Tang, A.M.; Fu, Z. Calcium Intake and cardiovascular Disease Risk: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2016, 165, 856–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopecky, S.; Bauer, D.C.; Gulati, M.; Nieves, J.W.; Singer, A.J.; Toth, P.P.; Underberg, J.; Wallace, T.; Weaver, C.M. Lack of Evidence Linking Calcium With or Without Vitamin D Supplementation to Cardiovascular Disease in Generally Healthy Adults: A Clinical Guideline from the National Osteoporosis Foundation and the American Society for Preventive Cardiology. Ann. Intern. Med. 2016, 165, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Sterne, J.A.C. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Cochrane, 2020. Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson-Hughes, B.; Dallal, G.E.; Krall, E.A. A controlled trial of the effect of cal-cium supplementation on bone density in postmenopausal women. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990, 323, 878–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, I.R.; Ames, R.W.; Evans, M.C.; Gamble, G.D.; Sharpe, S.J. Long-term effects of calcium supplementation on bone loss and fractures in postmenopausal women: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Med. 1995, 98, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, J.; Beach, M.; Mandel, J.; Van Stolk, R.; Haile, R.; Sandler, R.; Rothstein, R.; Summers, R.; Snover, D.; Beck, G.; et al. Calcium Supplements for the Prevention of Colorectal Adenomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonithon-Kopp, C.; Kronborg, O.; Giacosa, A.; Räth, U.; Faivre, J. Calcium and fibre supplementation in prevention of colorectal adenoma recurrence: A randomised intervention trial. Lancet 2000, 356, 1300–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazier, M.; Grados, F.; Kamel, S. Clinical and laboratory safety of one year’s use of a combination calcium + vitamin D tablet in ambulatory elderly women with vita-min D insufficiency: Results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, place-bo-controlled study. Clin. Ther. 2005, 27, 1885–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, R.L.; Devine, A.; Dhaliwal, S.S. Effects of calcium supplementation on clin-ical fracture and bone structure: Results of a 5-year, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in elderly women. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnick, S.L.; Broy, S.; Kaiser, F.; Teutsch, C.; Rosenberg, E.; Delucca, P.; Melton, M. Treatment with alendronate plus calcium, alendronate alone, or calcium alone for postmenopausal low bone mineral density. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2007, 23, 1341–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lappe, J.M.; Travers-Gustafson, D.; Davies, K.M. Vitamin D and calcium supple-mentation reduces cancer risk: Results of a randomized trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 1586–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, I.R.; Ames, R.; Mason, B. Randomized controlled trial of calcium supple-mentation in healthy, non-osteoporotic, older men. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008, 168, 2276–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chailurkit, L.O.; Saetung, S.; Thakkinstian, A. Discrepant influence of vitamin D status on parathyroid hormone and bone mass after two years of calcium supplemen-tation. Clin. Endocrinol. 2010, 73, 167–172. [Google Scholar]

- Bolland, M.J.; Grey, A.; Gamble, G.D.; Reid, I.R. Calcium and vitamin D supplements and health outcomes: A reanalysis of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) limited-access data set. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 1144–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avenell, A.; MacLennan, G.; Jenkinson, D.J.; McPherson, G.; McDonald, A.; Pant, P.R.; Grant, A.M.; Campbell, M.K.; Anderson, F.H.; Cooper, C.; et al. Long-Term Follow-Up for Mortality and Cancer in a Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial of Vitamin D3and/or Calcium (RECORD Trial). J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolland, M.J.; Barber, A.; Doughty, R.N.; Grey, A.; Gamble, G.; Reid, I.R. Differences between self-reported and verified adverse cardiovascular events in a randomised clinical trial. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e002334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolland, M.J.; Leung, W.; Tai, V.; Bastin, S.; Gamble, G.D.; Grey, A.; Reid, I.R. Calcium intake and risk of fracture: Systematic review. BMJ 2015, 351, h4580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, P.-J.; Zhang, C.; Tang, L.; Xian, Y.-Q.; Li, Y.-S.; Wang, W.-D.; Zhu, X.-H.; Qiu, H.-L.; He, J.; Zhou, Y.-H. Effect of calcium or vitamin D supplementation on vascular outcomes: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 169, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillemant, J.; Guillemant, S. Comparison of the suppressive effect of two doses (500 mg vs. 1500 mg) of oral calcium on parathyroid hormone secretion and on urinary cyclic AMP. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1993, 53, 304–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, S.M.; Gamble, G.D.; Stewart, A.; Horne, L.; House, M.E.; Aati, O.; Mihov, B.; Horne, A.M.; Reid, I.R. Acute and 3-month effects of microcrystalline hydroxyapatite, calcium citrate and calcium carbonate on serum calcium and markers of bone turnover: A randomised controlled trial in postmenopausal women. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112, 1611–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.H.; Booth, C.; Bunning, R. Postprandial metabolic responses to milk enriched with milk calcium are different from responses to milk enriched with calcium car-bonate. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 12, 109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Manson, J.E.; Sesso, H.D. Calcium Intake and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 2012, 12, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Ouyang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhao, G.; Bao, W.; Yan, M. Dietary calcium intake and mortality risk from cardiovascular disease and all causes: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, J.L.; Joannides, A.J.; Skepper, J.N. Human vascular smooth muscle cells undergo vesicle-mediated calcification in response to changes in extracellular calcium and phosphate concentrations: A potential mechanism for accelerated vascular calci-fication in ESRD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2004, 15, 2857–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, I.R.; Bolland, M.J.; Grey, A. Does calcium supplementation increase cardiovascular risk? Clin. Endocrinol. 2010, 73, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.-U.; Kirton, J.P.; Wilkinson, F.L.; Towers, E.; Sinha, S.; Rouhi, M.; Vizard, T.N.; Sage, A.P.; Martin, D.; Ward, D.T.; et al. Calcification is associated with loss of functional calcium-sensing receptor in vascular smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc. Res. 2008, 81, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, S.; Kim, K.J.; Chang, H.J. Impact of serum calcium and phosphate on coro-nary atherosclerosis detected by cardiac computed tomography. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 2873–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, T.; Nakashima, Y.; Harada, M.; Toyoshima, S.; Koshitani, O.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Nakayama, M. Effect of whole blood clotting time in rats with ionized hypocalcemia induced by rapid intravenous citrate infusion. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2006, 31, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, S.M.; Gamble, G.; Stewart, A.; Horne, A.; Reid, I.R. Acute effects of calcium supplements on blood pressure and blood coagulation: Secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial in post-menopausal women. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 114, 1868–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, I.R.; Gamble, G.D.; Bolland, M.J. Circulating calcium concentrations, vascular dis-ease and mortality: A systematic review. J. Intern. Med. 2016, 279, 524–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, S.C.; Burgess, S.; Michaëlsson, K. Association of Genetic Variants Related to Serum Calcium Levels With Coronary Artery Disease and Myocardial Infarction. JAMA 2017, 318, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.G.; Zeng, X.T.; Wang, J.; Liu, L. Association Between Calcium or Vitamin D Supplementation and Fracture Incidence in Community-Dwelling Older Adults A Sys-tematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 2017, 318, 2466–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Source (Study Name) | Country | Study Participants (Mean Age, y; Women, %) | Mean Dietary Calcium Intake | Duration of Supplementation, Y (Follow-Up Period, Y) | Intervention (vs. Placebo) | Outcomes Used | No. of Major Cardiovascular Events/No. of Participants | Data Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Mg/D) | Supplement Group | Placebo Group | |||||||

| Dawson-Hughes et al., 1990 [14] | United States | 361 healthy postmenopausal women (58.4; 100) | 406 | 2 (2) | Elemental calcium 500 mg/d (as citrate or citrate malate) | Stroke incidence: secondary endpoint | 0/238 | 1/123 | Unpublished data * |

| Reid et al., 1995 * [15] | New Zealand | 78 healthy postmenopausal women (58.5; 100) | 750 | 2 (4) | Elemental calcium 1000 mg/d (as lactate-gluconate carbonate) | Stroke incidence: secondary endpoint | 2/38 | 1/40 | Unpublished data * |

| Baron et al., 1999 [16] (CPPS) | United States | 930 patients with colorectal adenoma (61; 27.7) | 880 | 4 (4) | Elemental calcium 1200 mg/d (as carbonate) | Hospitalization due to cardiac disease or stroke incidence: secondary endpoint | 62/464 | 57/466 | Published data |

| Bonithon-Kopp et al., 2000 [17] (ECPIS) | 10 countries ** | 640 patients with a history of colorectal adenoma (59.1; 36.4) | 980 | 3 (3) | Elemental calcium 2000 mg/d (as carbonate or gluconate) | Stroke incidence: secondary endpoint | 1/204 | 0/212 | Unpublished data * |

| Brazier et al., 2005 [18] | France | 192 women with vitamin D deficiency (74.6; 100) | 736 | 1 (1) | Elemental calcium 1000 mg/d (as carbonate) + vitamin D3 800 IU/d | Cardiovascular events incidence: secondary endpoint | 6/95 | 5/97 | Published data |

| Prince et al., 2006 [19] (CAIFOS) | Australia | 1460 elderly women (70; 100) | 915 | 5 (5) | Elemental calcium (as carbonate) 1200 mg/d | IHD incidence: secondary endpoint | 56/730 | 51/730 | Published data |

| Bonnick et al., 2007 [20] | United States | 710 postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density (66.2; 100) | 1240 | 2 (2) | Elemental calcium 1000 mg/d (as carbonate) plus alendronate 10 mg/d vs. alendronate 10 mg/d | Stroke incidence: secondary endpoint | 1/282 | 2/281 | Unpublished data * |

| Lappe et al., 2007 * [21] | United States | 734 healthy postmenopausal women (66.7; 100) | 1070 | 4 (4) | Elemental calcium 1500 mg/d (as carbonate) or 1400 mg/d (as citrate) | MI and stroke: secondary endpoint | 7/446 | 6/288 | Unpublished data * |

| Reid et al., 2008 [22] | New Zealand | 323 healthy men (57; 0) | 870 | 2 (2) | Elemental calcium 600 mg/d or 1200 mg/d | CVD events or TIA: secondary endpoint | 8/216 | 1/107 | Published data |

| Chailurkit et al., 2010 [23] | Thailand | 336 physically active healthy postmenopausal women (65.8; 100) | 375 | 2 (2) | Elemental calcium 500 mg/d (as carbonate) | CVD incidence: secondary endpoint | 2/201 | 0/196 | Published data |

| Bolland et al., 2011 [24] (WHI) | United States | 16,718 postmenopausal women (62.9; 100) with no personal use of calcium: Reanalysis of the WHI | 801 | 7 (7) | Calcium 1000 mg/d + vitamin D3 400 IU/d | Clinical MI or revascularization + stroke: secondary endpoint | 618/8429 | 522/8289 | Published data |

| Avenell et al., 2012 [25] (RECORD) | United Kingdom | 5292 subjects with previous low-trauma fracture (77.2; 85) | 820 | 2–5 (5–8) | Elemental calcium 1000 mg/d (as carbonate) with or without vitamin D3 800 IU/d | CVD or Cerebrovascular disease: primary endpoint | 145/1311 | 136/1332 | Published data |

| Bolland et al., 2013 [26] (ACS) | New Zealand | 1471 healthy postmenopausal women (74; 100) | 857 | 5 (5) | Elemental calcium 1000 mg/d (as citrate) | MI or stroke: secondary endpoint | 65/732 | 46/739 | Published data |

| 2010, Bolland et al. [4] | 2011, Bolland et al. [5] | 2013, Mao et al. [28] | 2015, Lewis et al. [6] | 2016, Chung et al. [10] | Current Meta-Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conclusion on Calcium Supplementation and Risk of CVD | Increase | Increase | Might Increase | Not Increase | Not Associated, Small Risk and Not Clinically Important, if Any | Increase | |

| Main Findings: RR (95% CI), Number of Included Trials (Reference No.) *, Interpretation in Each Article | |||||||

| Myocardial Infarction (MI) |

|

|

|

| n.a. |

| |

| Stroke |

|

|

| n.a. | n.a. |

| |

| Cardiovascular disease (CVD): coronary heart disease (CHD) plus stroke |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Selection Criteria | Type of Trials | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials with >1 year of trial duration | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials | Randomized, placebo-controlled trials with at least one year of follow-up | Randomized placebo-controlled trials and open-label trials | Randomized controlled trials | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials |

| Inclusion of Trials with No Use of Placebos | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | |

| Study Participants | Participants aged >40 years | Participants aged >40 years | Not described | A mean cohort age >50 years | Generally healthy adults | Adults | |

| Inclusion of Unpublished Data | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Subgroup meta-analysis | Type of endpoints (MI, stroke, and death) | Type of endpoints (MI, stroke, and MI + stroke) | Type of endpoints (major cardiovascular events, MI, stroke) and sex | Type of endpoints (MI, angina pectoris and acute coronary syndrome, chronic coronary heart disease, and all-cause mortality) | n.a. | Type of endpoints (MI, angina pectoris, coronary revascularization, stroke, coronary heart disease, CVD), low risk of bias, population, age, gender, region, dosage, duration of supplementation, and data source (published or unpublished) | |

| Funding Source | The Health Research Council of New Zealand and the University of Auckland School of Medicine Foundation | The Health Research Council of New Zealand and the University of Auckland School of Medicine Foundation | National “Eleven Five” “Significant new drugs creation” special science and technology major, a major national science and technology projects, etc. | Not described | National Osteoporosis Foundation through Pfizer Consumer Healthcare in U.S. | None | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Myung, S.-K.; Kim, H.-B.; Lee, Y.-J.; Choi, Y.-J.; Oh, S.-W. Calcium Supplements and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials. Nutrients 2021, 13, 368. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020368

Myung S-K, Kim H-B, Lee Y-J, Choi Y-J, Oh S-W. Calcium Supplements and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials. Nutrients. 2021; 13(2):368. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020368

Chicago/Turabian StyleMyung, Seung-Kwon, Hong-Bae Kim, Yong-Jae Lee, Yoon-Jung Choi, and Seung-Won Oh. 2021. "Calcium Supplements and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials" Nutrients 13, no. 2: 368. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020368

APA StyleMyung, S.-K., Kim, H.-B., Lee, Y.-J., Choi, Y.-J., & Oh, S.-W. (2021). Calcium Supplements and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials. Nutrients, 13(2), 368. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020368