A Narrative Review about Nutritional Management and Prevention of Oral Mucositis in Haematology and Oncology Cancer Patients Undergoing Antineoplastic Treatments

Abstract

1. Introduction

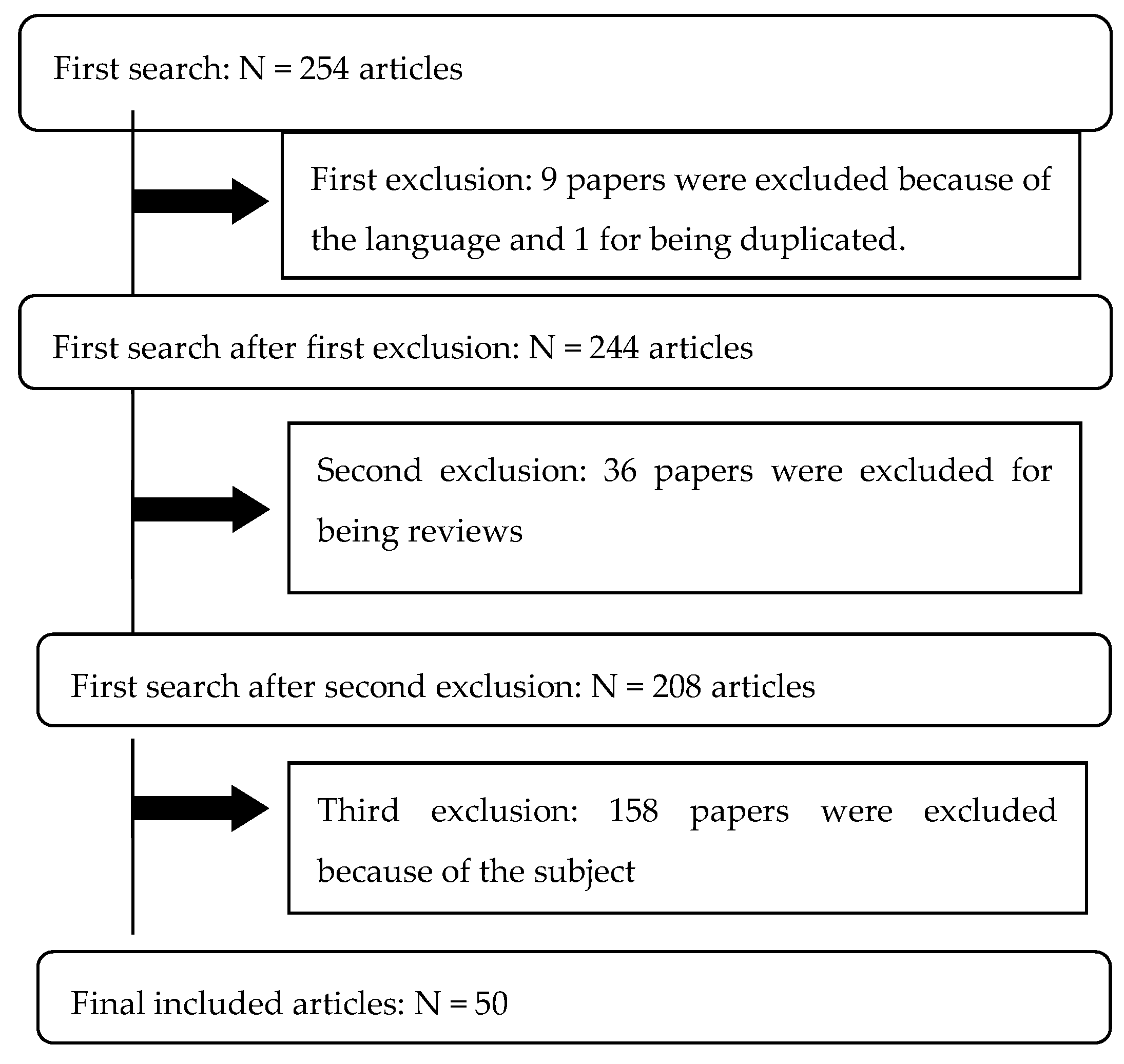

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Research

2.2. Study Eligibility, Selection, and Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Summary of the Studies Included

3.1.1. Paediatric Population

3.1.2. Glutamine

3.1.3. Honey

3.1.4. Other Dietary Components or Prevention Methods

4. Discussion

4.1. Paediatric Evidence

4.2. Glutamine

4.3. Honey

4.4. Vitamins and Amino Acids

4.5. Glycyrrhiza Glabra

4.6. Others

4.7. Strengths

4.8. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latest Global Cancer Data: Cancer Burden Rises to 18.1 Million New Cases and 9.6 Million Cancer Deaths in 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/cancer/prglobocanfinal.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2018).

- Efectos Secundarios de la Quimioterapia. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/CRC/PDF/Public/8459.96.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2019).

- Wardley, A.; Jayson, G.C.; Swindell, R.; Morgenstern, G.R.; Chang, J.; Bloor, R.; Fraser, C.J.; Scarffe, J.H. Prospective evaluation of oral mucositis in patients receiving myeloablative conditioning regimens and haemopoietic progenitor rescue. Br. J. Haematol. 2000, 110, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robien, K.; Schubert, M.M.; Bruemmer, B.; Lloid, M.E.; Potter, J.D.; Ulrich, C.M. Predictors of Oral Mucositis in Patients Receiving Hematopoietic Cell Transplants for Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 1268–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonis, S.; Antin, J.; Tedaldi, M.; Alterovitz, G. SNP-based Bayesian networks can predict oral mucositis risk in autologous stem cell transplant recipients. Oral Dis. 2013, 19, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalla, R.V.; Bowen, J.; Barasch, A.; Elting, L.; Epstein, J.; Keefe, D.M.; McGuire, D.B.; Migliorati, C.; Nicolatou-Galitis, O.; Peterson, D.E.; et al. MASCC/ISOO clinical practice guidelines for the management of mucositis secondary to cancer therapy. Cancer 2014, 120, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ansari, S.; Zecha, J.A.E.M.; Barasch, A.; De Lange, J.; Rozema, F.R.; Raber-Durlacher, J.E. Oral Mucositis Induced By Anticancer Therapies. Curr. Oral Health Rep. 2015, 2, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trancoso-Estrada, J. Capítulo 11: Enfermedades del aparato digestivo. In Manual de Codificación CIE-10-ES Diagnósticos, 2018 ed.; Pastor, M.D., Ed.; Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad: Madrid, España, 2018; p. 161. Available online: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/normalizacion/CIE10/CIE10ES_2018_norm_MANUAL_CODIF_DIAG_.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Sonis, S.T. Oral Mucositis, 1st ed.; Springer Healthcare: Tarporley, UK, 2012; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, F.; Oñate, R.E.; Roldán, R.; Cabrerizo, M.C. Measurement of secondary mucositis to oncohematologic treatment by means of different scale. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2005, 10, 412–421. Available online: http://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/medicor/v10n5/06.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.0. Available online: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_5x7.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2017).

- World Health Organization. WHO Handbook for Reporting Results of Cancer Treatment; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1979; p. 17. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37200 (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Peterson, D.E.; Bensadoun, R.-J.; Roila, F. Management of oral and gastrointestinal mucositis: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann. Oncol. 2011, 22, vi78–vi84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elad, S.; Cheng, K.K.F.; Lalla, R.V.; Yarom, N.; Hong, C.; Logan, R.M.; Bowen, J.; Gibson, R.; Saunders, D.P.; Zadik, Y.; et al. MASCC/ISOO clinical practice guidelines for the management of mucositis secondary to cancer therapy. Cancer 2020, 126, 4423–4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.M.; Schroeder, G.; Skubitz, K.M. Oral glutamine reduces the duration and severity of stomatitis after cytotoxic cancer chemotherapy. Cancer 1998, 83, 1433–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.M.; Ramsay, N.K.C.; Shu, X.; Rydholm, N.; Rogosheske, J.; Nicklow, R.; Weisdorf, D.J.; Skubitz, K.M. Effect of low-dose oral glutamine on painful stomatitis during bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998, 22, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.-J.; Huang, M.-Y.; Fang, P.-T.; Chen, F.; Wang, Y.-T.; Chen, C.-H.; Yuan, S.-S.; Huang, C.-M.; Luo, K.-H.; Wang, Y.-Y.; et al. Randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluating oral glutamine on radiation-induced oral mucositis and dermatitis in head and neck cancer patients. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 606–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsujimoto, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Wasa, M.; Takenaka, Y.; Nakahara, S.; Takagi, T.; Tsugane, M.; Hayashi, N.; Maeda, K.; Inohara, H.; et al. L-glutamine decreases the severity of mucositis induced by chemoradiotherapy in patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Oncol. Rep. 2014, 33, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Yamaguchi, K.; Osada, S.; Shimokawa, T.; Yoshida, K. Elemental diet plus glutamine for the prevention of mucositis in esophageal cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: A feasibility study. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 933–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachón-Ibañez, J.; Pereira-Cunill, J.L.; Osorio-Gómez, G.F.; Irles-Rocamora, J.A.; Serrano-Aguayo, P.; Quintana-Ángel, B.; Fuentes-Pradera, J.; Chaves-Conde, M.; Ortiz-Gordillo, M.J.; García-Luna, P.P. Prevention of oral mucositis secondary to antineoplastic treatments in head and neck cancer by supplementation with oral glutamine. Nutr. Hosp. 2018, 35, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.-C.; Lai, Y.-C.; Hung, J.-C.; Chang, C.-Y. Oral glutamine supplements reduce concurrent chemoradiotherapy-induced esophagitis in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Medicine 2019, 98, e14463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anturlikar, S.D.; Azeemuddin, M.M.; Varma, S.; Mallappa, O.; Niranjan, D.; Krishnaiah, A.B.; Hegde, S.M.; Rafiq, M.; Paramesh, R. Turmeric based oral rinse “HTOR-091516” ameliorates experimental oral mucositis. AYU Int. Q. J. Res. Ayurveda 2019, 40, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.K.; Hong, S.Y.; Jeon, S.J.; Namgung, H.W.; Lee, E.; Lee, E.; Bang, S.-M. Efficacy of parenteral glutamine supplementation in adult hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients. Blood Res. 2019, 54, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumsky, A.; Bilan, E.; Sanz, E.; Petrovskiy, F. Oncoxin nutritional supplement in the management of chemotherapy- and/or radiotherapy-associated oral mucositis. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 10, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widjaja, N.A.; Pratama, A.; Prihaningtyas, R.A.; Irawan, R.; Ugrasena, I. Efficacy Oral Glutamine to Prevent Oral Mucositis and Reduce Hospital Costs During Chemotherapy in Children with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2020, 21, 2117–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, K.; Ferdous, T.; Kobayashi, H.; Ueyama, Y. Elemental Diet Accelerates the Recovery from Oral Mucositis and Dermatitis Induced by 5-Fluorouracil through the Induction of Fibroblast Growth Factor 2. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterom, N.; Dirks, N.F.; Heil, S.G.; de Jonge, R.; Tissing, W.J.E.; Pieters, R.; van den Heuvel-Eibrink, M.M.; Heijboer, A.C.; Pluijm, S.M.F. A decrease in vitamin D levels is associated with methotrexate-induced oral mucositis in 66 children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Zhu, X.; Li, D.; Cheng, T. Effects of a compound vitamin B mixture in combination with GeneTime® on radiation-induced oral mucositis. J. Int. Med. Res. 2019, 47, 2126–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejatinamini, S.; Debenham, B.J.; Clugston, R.D.; Mawani, A.; Parliament, M.; Wismer, W.V.; Mazurak, V.C. Poor Vitamin Status is Associated with Skeletal Muscle Loss and Mucositis in Head and Neck Cancer Patients. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, Y.; Ueno, T.; Yoshida, N.; Akutsu, Y.; Takeuchi, H.; Baba, H.; Matsubara, H.; Kitagawa, Y.; Yoshida, K. The effect of an elemental diet on oral mucositis of esophageal cancer patients treated with DCF chemotherapy: A multi-center prospective feasibility study (EPOC study). Esophagus 2018, 15, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, S.; Soni, T.P.; Sharma, L.M.; Patni, N.; Gupta, A.K. A Randomized Controlled Trial to Evaluate the Role and Efficacy of Oral Glutamine in the Treatment of Chemo-radiotherapy-induced Oral Mucositis and Dysphagia in Patients with Oropharynx and Larynx Carcinoma. Cureus 2019, 11, e4855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamgain, R.K.; Gupta, M.; Mamgain, P.; Verma, S.K.; Pruthi, D.S.; Kandwal, A.; Saini, S. The efficacy of an ayurvedic preparation of yashtimadhu (Glycyrrhiza glabra) on radiation-induced mucositis in head-and-neck cancer patients: A pilot study. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2020, 16, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, K.; Minami, H.; Ferdous, T.; Kato, Y.; Umeda, H.; Horinaga, D.; Uchida, K.; Park, S.C.; Hanazawa, H.; Takahashi, S.; et al. The Elental® elemental diet for chemoradiotherapy-induced oral mucositis: A prospective study in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 10, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Hegde, S.K.; Rao, P.; Dinakar, C.; Thilakchand, K.R.; George, T.; Baliga-Rao, M.P.; Palatty, P.L.; Baliga, M.S. Honey Mitigates Radiation-Induced Oral Mucositis in Head and Neck Cancer Patients without Affecting the Tumor Response. Foods 2017, 6, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branda, R.F.; Naud, S.J.; Brooks, E.M.; Chen, Z.; Muss, H. Effect of vitamin B12, folate, and dietary supplements on breast carcinoma chemotherapy–induced mucositis and neutropenia. Cancer 2004, 101, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, T.; Nakajima, Y.; Nishikage, T.; Ryotokuji, T.; Miyawaki, Y.; Hoshino, A.; Tokairin, Y.; Kawada, K.; Nagai, K.; Kawano, T. A prospective study of nutritional supplementation for preventing oral mucositis in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 26, 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Sá, O.M.d.S.; Lopes, N.N.F.; Alves, M.T.S.; Caran, E.M.M. Effects of Glycine on Collagen, PDGF, and EGF Expression in Model of Oral Mucositis. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nihei, S.; Sato, J.; Komatsu, H.; Ishida, K.; Kimura, T.; Tomita, T.; Kudo, K. The efficacy of sodium azulene sulfonate L-glutamine for managing chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis in cancer patients: A prospective comparative study. J. Pharm. Health Care Sci. 2018, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, S.; Saha, A.; Azam, M.; Mukherjee, A.; Sur, P.K. Role of oral glutamine in alleviation and prevention of radiation-induced oral mucositis: A prospective randomized study. S. Asian J. Cancer 2014, 3, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Üçüncü, H.; Ertekin, M.V.; Yörük, Ö.; Sezen, O.; Özkan, A.; Erdoğan, F.; Kızıltunç, A.; Gündoğdu, C. Vitamin E and L-carnitine, Separately or in Combination, in The Prevention of Radiation-induced Oral Mucositis and Myelosuppression: A Controlled Study in A Rat Model. J. Radiat. Res. 2006, 47, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanat, A.; Ahmed, A.; Kazmi, A.; Aziz, B. The effect of honey on radiation-induced oral mucositis in head and neck cancer patients. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2017, 23, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlesko, A.M.; Ramacciati, N.; Serenella, P.; Simonetta, S.; Fiorucci, S.; Pierini, D.; Mancini, M.; Merolla, M.S.; Lancellotta, V.; Cynthia, A. Effects of topical polydeoxyribonucleotide on radiation-induced oral mucositis. Tech. Innov. Patient Support Radiat. Oncol. 2018, 7, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, A.C.; Barbosa, T.R.; da Silva, F.L.; de Carvalho, A.F.; Stephani, R.; Dos Santos, K.B.; Atalla, A.; Hallack-Neto, A.E. Supplementation with concentrated milk protein in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Nutrients 2017, 37, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, Y.; Ishibashi, N.; Yamaguchi, K.; Uchida, S.; Kamei, H.; Nakayama, G.; Hirakawa, H.; Tanigawa, M.; Akagi, Y. Preventive effects of amino-acid-rich elemental diet Elental® on chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis in patients with colorectal cancer: A prospective pilot study. Support. Care Cancer 2015, 24, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Al Jaouni, S.K.; Al Muhayawi, M.S.; Hussein, A.; Elfiki, I.; Al-Raddadi, R.; Al Muhayawi, S.M.; Almasaudi, S.; Kamal, M.A.; Harakeh, S. Effects of Honey on Oral Mucositis among Pediatric Cancer Patients Undergoing Chemo/Radiotherapy Treatment at King Abdulaziz University Hospital in Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 2017, 5861024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Vaquero, D.; Gutierrez-Bayard, L.; Rodriguez-Ruiz, J.; Saldaña-Valderas, M.; Infante-Cossio, P. Double-blind randomized study of oral glutamine on the management of radio/chemotherapy-induced mucositis and dermatitis in head and neck cancer. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 6, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlader, D.; Singh, V.; Mohammad, S.; Gupta, S.; Pal, U.S.; Pal, M. Effect of Topical Application of Pure Honey in Chemo-radiation-Induced Mucositis and Its Clinical Benefits in Improving Quality of Life in Patients of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2018, 18, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsass, F.T. A Sweet Solution: The Use of Medical-grade Honey on Oral Mucositis in the Pediatric Oncology Patient. Wounds 2017, 29, 115–117. Available online: https://www.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/wounds/rapid-communication/sweet-solution-use-medical-grade-honey-oral-mucositis-pediatric (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Elkerm, Y.; Tawashi, R. Date Palm Pollen as a Preventative Intervention in Radiation- and Chemotherapy-Induced Oral Mucositis: A pilot study. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2014, 13, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raeessi, M.A.; Raeessi, N.; Panahi, Y.; Gharaie, H.; Davoudi, S.M.; Saadat, A.; Zarchi, A.A.K.; Raeessi, F.; Ahmadi, S.M.; Jalalian, H. “Coffee plus Honey” versus “topical steroid” in the treatment of Chemotherapy-induced Oral Mucositis: A randomised controlled trial. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 14, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baydar, M.; Dikilitas, M.; Sevinc, A.; Aydogdu, I. Prevention of Oral Mucositis Due to 5-Fluorouracil Treatment with Oral Cryotherapy. Prevention of oral mucositis due to 5-fluorouracil treatment with oral cryotherapy. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2005, 97, 1161–1164. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16173332/ (accessed on 23 June 2021). [PubMed]

- Peterson, D.E.; Jones, J.B.; Petit, R.G. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of Saforis for prevention and treatment of oral mucositis in breast cancer patients receiving anthracycline-based chemotherapy. Cancer 2007, 109, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogh, S.E.; Deshmukh, S.; Berk, L.B.; Dueck, A.C.; Roof, K.; Yacoub, S.; Gergel, T.; Stephans, K.; Rimner, A.; De Nittis, A.; et al. A Randomized Phase 2 Trial of Prophylactic Manuka Honey for the Reduction of Chemoradiation Therapy–Induced Esophagitis During the Treatment of Lung Cancer: Results of NRG Oncology RTOG 1012. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Psych. 2017, 97, 786–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samdariya, S.; Lewis, S.; Kauser, H.; Ahmed, I.; Kumar, D. A randomized controlled trial evaluating the role of honey in reducing pain due to radiation induced mucositis in head and neck cancer patients. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2015, 21, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, C.; Munemoto, Y.; Mishima, H.; Nagata, N.; Oshiro, M.; Kataoka, M.; Sakamoto, J.; Aoyama, T.; Morita, S.; Kono, T. Double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized phase II study of TJ-14 (Hangeshashinto) for infusional fluorinated-pyrimidine-based colorectal cancer chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2015, 76, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, E.; Bowen, J.; Stringer, A.; Mayo, B.; Plews, E.; Wignall, A.; Greenberg, N.; Schiffrin, E.; Keefe, D. Investigation of Effect of Nutritional Drink on Chemotherapy-Induced Mucosal Injury and Tumor Growth in an Established Animal Model. Nutrients 2013, 5, 3948–3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayachandran, S.; Balaji, N. Evaluating the effectiveness of topical application of natural honey and benzydamine hydrochloride in the management of radiation mucositis. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2012, 18, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugita, J.; Matsushita, T.; Kashiwazaki, H.; Kosugi, M.; Takahashi, S.; Wakasa, K.; Shiratori, S.; Ibata, M.; Shono, Y.; Shigematsu, A.; et al. Efficacy of folinic acid in preventing oral mucositis in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients receiving MTX as prophylaxis for GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012, 47, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, J.B.; Skovsgaard, T.; Bork, E.; Damstrup, L.; Ingeberg, S. Double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study of chlorhexidine prophylaxis for 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis with nonblinded randomized comparison to oral cooling (cryotherapy) in gastrointestinal malignancies. Cancer 2008, 112, 1600–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Chandola, H.M.; Agarwal, S.K. Protective effect of Yashtimadhu (Glycyrrhiza glabra) against side effects of radiation/chemotherapy in head and neck malignancies. AYU Int. Q. J. Res. Ayurveda 2011, 32, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornley, I.; Lehmann, L.; Sung, L.; Holmes, C.; Spear, J.M.; Brennan, L.; Vangel, M.; Bechard, L.J.; Richardson, P.; Duggan, C.; et al. A multiagent strategy to decrease regimen-related toxicity in children undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2004, 10, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyama, S.; Sato, T.; Tatsumi, H.; Hashimoto, A.; Tatekoshi, A.; Kamihara, Y.; Horiguchi, H.; Ibata, S.; Ono, K.; Murase, K.; et al. Efficacy of Enteral Supplementation Enriched with Glutamine, Fiber, and Oligosaccharide on Mucosal Injury following Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Case Rep. Oncol. 2014, 7, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, H.; Momota, Y.; Kani, K.; Aota, K.; Yamamura, Y.; Yamanoi, T.; Azuma, M. γ-tocotrienol prevents 5-FU-induced reactive oxygen species production in human oral keratinocytes through the stabilization of 5-FU-induced activation of Nrf2. Int. J. Oncol. 2015, 46, 1453–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha-Hosseini, F.; Pourpasha, M.; Amanlou, M.; Moosavi, M.-S. Mouthwash Containing Vitamin E, Triamcinolon, and Hyaluronic Acid Compared to Triamcinolone Mouthwash Alone in Patients With Radiotherapy-Induced Oral Mucositis: Randomized Clinical Trial. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 614877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeshurun, M.; Rozovski, U.; Pasvolsky, O.; Wolach, O.; Ram, R.; Amit, O.; Zuckerman, T.; Pek, A.; Rubinstein, M.; Sela-Navon, M.; et al. Efficacy of folinic acid rescue following MTX GVHD prophylaxis: Results of a double-blind, randomized, controlled study. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 3822–3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanakitsakul, P.; Chongviriyaphan, N.; Pakakasama, S.; Apiwattanakul, N. Effect of vitamin A on intestinal mucosal injury in pediatric patients receiving hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and chemotherapy: A quasai-randomized trial. BMC Res. Notes 2020, 13, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, L.; Robinson, P.; Treister, N.; Baggott, T.; Gibson, P.; Tissing, W.; Wiernikowski, J.; Brinklow, J.; Dupuis, L.L. Guideline for the prevention of oral and oropharyngeal mucositis in children receiving treatment for cancer or undergoing haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2017, 7, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friend, A.; Rubagumya, F.; Cartledge, P.T. Global Health Journal Club: Is Honey Effective as a Treatment for Chemotherapy-induced Mucositis in Paediatric Oncology Patients? J. Trop. Pediatr. 2017, 64, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.M.; Lalla, R.V. Glutamine for Amelioration of Radiation and Chemotherapy Associated Mucositis during Cancer Therapy. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, T.; Tian, X.; Xu, L.-L.; Chen, W.-Q.; Pi, Y.-P.; Zhang, L.; Wan, Q.-Q.; Li, X.-E. Oral Glutamine May Have No Clinical Benefits to Prevent Radiation-Induced Oral Mucositis in Adult Patients With Head and Neck Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münstedt, K.; Männle, H. Using Bee Products for the Prevention and Treatment of Oral Mucositis Induced by Cancer Treatment. Molecules 2019, 24, 3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Xu, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, C.C.; Xie, W.; Jiménez-Herrera, M.F.; Chen, W. Impact of honey on radiotherapy-induced oral mucositis in patients with head and neck cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2020, 9, 1431–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarom, N.; Hovan, A.; Bossi, P.; Ariyawardana, A.; Jensen, S.B.; Gobbo, M.; Saca-Hazboun, H.; Kandwal, A.; Majorana, A.; Ottaviani, G.; et al. Systematic review of natural and miscellaneous agents for the management of oral mucositis in cancer patients and clinical practice guidelines—Part 1: Vitamins, minerals, and nutritional supplements. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 3997–4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard, S.A. Exploring the Pivotal Immunomodulatory and Anti-Inflammatory Potentials of Glycyrrhizic and Glycyrrhetinic Acids. Mediat. Inflamm. 2021, 2021, 6699560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-González, A.; García-Quintanilla, M.; Guerrero-Agenjo, C.M.; López, J.; Guisado-Requena, I.M.; Rabanales-Sotos, J. Eficacy of Cryotherapy in the Prevention of Oral Mucosistis in Adult Patients with Chemotherapy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author (Year) | N | Study Design | Objective | Intervention | Time (Months) | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huang et al. (2019) [19] | 59 | RCT Phase III, double-blind | To evaluate whether oral glutamine prevents acute toxicities (OM and dermatitis) secondary to the treatment with RT in patients with head and neck cancers. | Glutamine (TG); Control, maltodextrin (CG); NCI CTCAE 4.03 version. | 19 | CG developed more OM (grades 2–4) than TG; nevertheless, the efficacy of the treatment with oral glutamine was not meaningful after RT in head and neck cancers. |

| Tsujimoto et al. (2015) [20] | 40 | RCT, double-blind | To evaluate whether oral glutamine reduces mucositis severity induced by CRT in patients with head and neck cancer. | Glutamine (TG); Placebo (PG); NCI CTCAE 3.0 version. | 36 | Oral glutamine reduced OM severity produced by CT in head and neck cancer patients with a maximum mean grade of OM lower for TG than for PG, a duration without meaningful difference between both groups, and a shorter duration of artificial nutrition required in TG. |

| Tanaka et al. (2016) [21] | 30 | RCT Phase II | To assess whether glutamine and the combination of glutamine and elemental diet reduce the incidence of CT induced OM in patients with oesophageal cancers. | Placebo (PG); Glutamine (TG); Glutamine + elemental diet (CTG); NCI CTCAE 3.0 version. | 36 | No differences between PG and TG |

| Pachón-Ibañez et al. (2018) [22] | 262 | Prospective cohort study | To evaluate whether oral glutamine prevents mucositis induced by oncological therapies (CRT or RT) in patients with head and neck cancer. | Oral glutamine (TG); Placebo (PG); RTOG/EORTC (MO and oesophagitis). | - | More OM in PG (RR:1.78), without remarkable differences in severity. Higher odynophagia in PG (RR:2.87), with more severity (R = 4.33). In PG, more discontinuity in the treatment. |

| Chang et al. (2019) [23] | 60 | RCT Triple-blind | To measure the impact of oral glutamine as a supplement for the prevention of oesophagitis induced by CRT in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (stages III–IV). | Placebo (PG); Oral glutamine (TG); ARIE, acute radiation induced oesophagitis. | 12 | TG had less severe ARIE than PG, as well as a reduction in the incidence of weight loss in TG. |

| Anturlikar et al. (2019) [24] | 20 | In vitro and in vivo study | To measure the safety and efficacy of “HTOR-091516” (Tumeric, Triphala, and honey) as a treatment for OM induced by 5-FU (CT). | IN VITRO: gingival human fibroblast, mouse connective tissue, and human oral reconstructed epidermis culture. Later treatment with “HTOR-091516” and MTT test (cytotoxicity) + TNF-α inhibition test (inflammation)+ test INVITTOX SKINETHIC ™ (irritation). IN VIVO: two groups of rats (control (PG) and treatment with “HTOR-091516” (TG)). In TG: drops on the induced ulcer in every animal during their treatment with CT. | 0.5 (14 days) | The average weight loss in TG was lower; there also was less mortality and a reduction in OM grade (WHO scale). The product is proposed to prevent OM. |

| Cho et al. (2019) [25] | 91 | CT | To assess the effect of glutamine-enriched parenteral nutrition (PN) on weight, infections, complications (mucositis, neutropenia, and graft-versus-host disease), and mortality in patients who underwent HSCT transplantation. | Control (CG); Glutamine (TG) through Dipeptiven© (bottle). | 48 | No significant association in the case of OM duration. A reduction in 100-days mortality for TG was noted. |

| Shumsky et al. (2019) [26] | 15 | Pilot RCT | To evaluate the efficacy of Oncoxin (ONCX) in oncologic patients with OM who underwent CT, RT or both. | Control group (CG); Group ONCX (OG); WHO Scale. | 0.6 (20 days) | Lower-grade OM was found in OG (after 7 days of treatment and towards the end of their treatment). |

| Widjaja et al. (2020) [27] | 48 | Double-blind RCT | To measure whether oral glutamine prevents OM during CT (methotrexate (MTX) in paediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL). | Placebo group (PG); Oral glutamine group (TG); WHO Scale. | 0.5 (14 days) | There was a reduction in the incidence and severity of OM in TG after CT. |

| Harada et al. (2018) [28] | 50 | In vitro and in vivo study | To appraise the efficacy of Elental© (dietetic liquid formulation enriched with amino acids, which is a source of L-glutamine) in 5-FU (CT)-induced OM and dermatitis treatment. | In vivo: Saline solution (PG); Dextrin group (DG); Elental group (EG). | 0.25 (8 days) | In vivo, OM healed faster than in EG. |

| Oosterom et al. (2019) [29] | 99 (A) and 81 (B) | Cohort study | (1) To study the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in paediatric patients; (2) To establish a link between vitamin D levels and methotrexate (MTX)-induced OM in paediatric acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL). | Vitamin D levels before and after MTX therapy. After MTX, classification in two groups depending on OM grade: ≥3 or ≤3. NCI CTCAE 3.0 version. | 2004–2012 | There was no association between basal vitamin D levels and MTX-induced OM, but low levels of vitamin D during MTX therapy were found to be related to severe OM. |

| Sun et al. (2019) [30] | 100 | Double-blind RCT | To examine the effects of a group B multivitamin complex combined with GeneTime© (human recombinant growth factor) on the treatment of OM in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing RT. | Control group with vitamin B complex.Observational group with (OG) vitamin B complex + GeneTime©. RTOG scale. | 12 | Less severity, affected area, and healing time of the OM ulcers in OG. |

| Nejatinamini et al. (2018) [31] | 28 | Cohort study | To evaluate the changes in vitamin status during the treatment of head and neck cancers related to body composition, inflammation, and mucositis. | Dietetic intake measurement (3 days). Vitamin levels (vitamins D, E, B9, and B12) basal (before treatment) and 6 to 8 weeks after RT treatment (with or without CT); C-reactive protein (CRP) measurement. C-reactive protein (CRP) baseline before and after 6 to 8 weeks of RT treatment, either with or without QT after treatment. | 1–1.5 | Higher rates of OM were observed related to less vitamin D, B12, E, and B9 intake and lower blood levels of vitamin A and D. |

| Tanaka et al. (2018) [32] | 19 | RCT | To measure the intake of Elental© during two cycles of CT and to determine the incidence of OM in patients with oesophageal cancers treated with CT who completed their intake and those who did not completed it. | Elental© group (CG); Elental© group with uncompleted treatment (UG); CTCAE 3.0 version. | 2 (56 days) | Less severity of OM in CG during CT with the use of Elental©. |

| Pathak et al. (2019) [33] | 56 | RCT | To assess the efficacy and role of oral glutamine in the treatment of OM and dysphagia induced by chemoradiotherapy (CRT) in patients with oropharynx and larynx carcinoma. | Control group (CG); Glutamine group (TG); NCI CTCAE 4.03 version. | 1.75 (49 days) | TG had fewer hospitalizations due to OM and dysphagia. More incidence and severity of OM in CG. |

| Mamgain et al. (2020) [34] | 127 | RCT | To evaluate the efficacy of an ayurvedic preparation (based on Glycyrrhiza glabra) in order to decrease the severity of mucositis in patients with head and neck cancers who received chemoradiotherapy (CRT). | Comparison between basal and post-RT characteristics: (1) Conventional OM treatment (antiacids and anaesthetics) (CTG); (2) Conventional treatment and ayurvedic preparation (ATG); (3) Honey and conventional treatment (HTG). | 24 | Less severity, less pain, and shorter onset time of mucositis, both in ATG and HTG, but especially in ATG. |

| Harada et al. (2019) [35] | 50 | Open RCT | To evaluate changes in OM (injuries’ size, pain, and redness + CRP in plasma) in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma undergoing CRT or RT with Elental© administration. | Elental group (EG); Non-Elental group as the control (CG); CTCAE 4.0 version. | 24 | In EG, milder OM development in CRT; no difference in RT. |

| Rao et al. (2017) [36] | 49 | Blinded single-centre RCT | To evaluate whether honey causes interference with RT-induced tumoral response or whether it exhibits a positive effect against OM in patients with head and neck cancer. | Povidone–iodine group (CG); Honey group (HG); RTOG scale. | 6 | Lower incidence of OM and less severity in HG. The implications for treatment interruption were not significant. |

| Branda et al. (2004) [37] | 68 | Pilot cohort study | To study the influence of B12 vitamin, folate, and dietetic supplements on CT-induced toxicity in breast cancer patients. | Blood samples (B12, B9, and neutrophils) before/after the first CT cycle; Questionnaires about supplement usage; OM grading (author-modified CTCAE); 68 subjects + historical controls. | - | No evidence of influence was found. |

| Okada et al. (2017) [38] | 20 | Pilot single-centre RCT | To evaluate the influence of Elental© on CT-induced OM and diarrhoeas in patients with oesophageal cancer. | IG: use of Elental©; CG: no Elental used; Questionnaires and clinical examination; CTCAE 4.0 version. | 0.5 (14 days) | Less severe OM incidence in IG. |

| De Sousa et al. (2018) [39] | 40 | In vivo study | To evaluate the effects of glycine in the expression of collagen and platelet and epidermal growth factors (PDGF, EGF) in an OM murine model. | Control group (CG); Intervention group (IG: glycine supplementation); Measurement of collagen percentage and type and EGF and PDGF percentage. | - | Positive effects in IG, with a better recovering rate (collagen increase and growth factors reduction). |

| Nihei et al. (2018) [40] | 67 | Single-centre RCT | To evaluate the efficacy and safety of L-Glutamine sodium azulene sulphonate in the treatment of CT-induced OM in patients with colorectal and breast cancer. | Intervention group (IG); Control group (CG: standard oral hygiene); CTCAE 4.0 version; NRS pain scale. | 24 | Lesser OM severity in IG. No significant differences were found regarding incidence. |

| Chattopadhyay et al. (2014) [41] | 70 | Single-centre RCT | To evaluate the influence of oral glutamine on RT-induced OM in patients with head and neck cancer. | Intervention group with oral glutamine (IG); No placebo control group (CG); WHO scale. | 8 | Lower incidence, severity, and duration of RT-induced OM in IG. |

| Üçüncü et al. (2006) [42] | 35 | Laboratory CT (rats) | To determine the preventive effect of Vitamin E (VE) and L-Carnitine (LC), alone or in combination, on OM and myelosuppression by RT. | 5 groups: (1) No RT (control: saline + simulated radiation); (2) RT; (3) RT + VE; (4) RT + LC; (5) RT + VE + LC. OM measurement scale: Parkins et al.; Clinical/histopathological OM was evaluated; Levels of SOD and CAT (antioxidants) and MDA (oxidative stress indicator). | Follow-up: 4 days pre-RT—10 days post-RT. | VE and LC proved to be radioprotective agents on their own and not combined together, with lower severity and longer time to histological appearance of OM. Good tolerance and no adverse effects. |

| Amanat et al. (2017) [43] | 82 | Single-centre RCT | To assess the effect of honey on clinical grades of OM. | Honey group (HG); Control saline group (CG); RTOG scale. | 12 | Lower incidence and severity of OM in HG during the RT. |

| Podlesko et al. (2018) [44] | 3 | Case series | To evaluate the effects of topical application of deoxyribonucleic acid on three OM (moderate–severe) cases in patients with head and neck cancer. | Oral spray of polydeoxyribonucleotide (PDRN) as treatment. | 1 | Increased relief and remission of OM over time, without interruption in treatment or opioid intake. |

| Perrone et al. (2017) [45] | 73 | CT | To analyse the influence of dietary supplementation with whey protein concentrate (WPC) on the incidence of OM in patients undergoing HSCT. | WPC group (WG); Historical controls (CG); WG was sub-stratified into: consumed <80% PWC (WG1) or ≥80% (WG2) of the offered dose; WHO and CTCAE 4.0 version. | Not specified | No significant differences between WG and CG in incidence, duration, and severity of OM concerns. However, in WG2, shorter duration and lower incidence of severe OM was found. |

| Ogata et al. (2017) [46] | 22 | Pilot prospective study | To evaluate the preventive effects of Elental ® on CT-induced OM in patients with colorectal cancer (CRC). | 22 patients in Elental (1 group); CTCAE 3.0 version. | 36 | Significantly reduced CT (5-FU)-induced OM grade. |

| Al Jouni et al. (2017) [47] | 40 | Open RCT | To evaluate the effects of honey on grade 3–4 OM, reduction in bacterial/fungal infections, duration of OM episodes, and body weight in paediatric leukaemia patients undergoing CT or RT. | Control group (CG) with Lidocaine, Mycostatin, Daktarin, and oral cleaning; Experimental group (HG) with same routine as CG + honey (4–6 times/day); WHO scale. | 12 | Significant reduction in severity and pain in HG. Significant improvement in weight and time to OM onset in HG. |

| Lopez-Vaquero et al. (2017) [48] | 49 | Phase II double-blind RCT | To evaluate whether glutamine is effective in reducing the incidence and severity of mucositis and dermatitis induced by RT or CRT in patients with head and neck cancer. | L-Glutamine group (TG); Placebo group with malto-dextrine (PG); CTCAE 3.0 version. | 6 | Incidence and severity with no significant differences between groups. |

| Howlader et al. (2019) [49] | 40 | RCT (single-blinded). | To assess whether honey improves mucositis injuries and the quality of life of patients with RT/CT-induced OM (for head and neck cancer). | Treatment group (HG) with honey (both rinsed and ingested honey); Control group (CG) with saline solution; CTCAE. | From CT start—4 weeks after RT. | Less OM and associated symptoms induced by RT in HG. Shorter time towards the recovery of a regular quality of life. |

| Elsass (2017) [50] | 10 (3 analysed) | Case series | The aim was to improve OM (oral comfort and feeding) with standard oral care and the use of Leptospermum honey in paediatric oncology patients after proven CT. | Application of honey on the buccal surface with a cotton swab, 3 times/day, Then spat or suctioned out. | - | Shorter healing time with lower pain rate in all cases. |

| Elkerm and Tawashi (2014) [51] | 20 | Pilot study | To evaluate whether date palm pollen (DPP) can be effective in the prevention and treatment of RT- and CT-induced OM in patients with head and neck cancer. | DPP group (one daily suspension); Control group (CG) (antifungal, rebamipide, and oral analgesia); OMAS score and visual analogue scale for mouth pain and dysphagia. | 1.5 (6 weeks) | Significant reduction in incidence, severity, and pain in OM and dysphagia in DPP. |

| Raeessi et al. (2014) [52] | 61 | Single-centre double-blind RCT | To evaluate the effects of coffee + honey in the treatment of OM by CT and compare them with the effects of steroids. | 3 groups: (1) Betamethasone group (EG); (2) Honey group (HG); (3) Honey + coffee group (HCG); WHO scale. | 36 2011–2013 | Significant reduction in the severity of OM in all three groups. |

| Baydar et al. (2005) [53] | 99 | CT | To research the effects of local cryotherapy on the prevention of CT (5-FU)-induced OM. | Intervention group (IG): CT courses with local cryotherapy (ice in the mouth during the CT course up to 10 min afterwards); Control group (CG): no-cryotherapy courses. | Not specified. | 5-FU-induced OM incidence lower in GI (OR = 11.5). |

| Peterson et al. (2007) [54] | 305 | Phase III, double-blind RCT | To observe the efficacy of Saforis ® in the prevention and treatment of OM caused by CT treatment in breast cancer. | Saforis group (SG); Placebo group (PG) (with subsequent cross-linking); WHO scale (ulcer grading scale); OMAS scale (ulceration measurement). | Not specified. | Lower severity and incidence rate in SG. |

| Fogh et al. (2016) [55] | 119 | Multicentric phase II RCT | To evaluate the effect of Manuka honey (liquid and tablets) in the prevention of RT-induced oesophagitis in lung cancer patients. | G1: Manuka honey (liquid); G2: Manuka honey (tablets); G3: control, standard care. Measurements: odynophagia (NRPS scale), pain, opioid use, dysphagia, weight loss, quality of life, and nutritional status. | 12 | There were no significant differences for groups G1, G2, or G3, so the use of honey did not prove to be superior to standard health care. |

| Samdariya et al. (2015) [56] | 69 | Open RCT | To study the intake of honey in pain relief caused by RT-induced OM in patients with head and neck cancer. | (1) Gargle with soda and benzidamine (PG); (2) Gargle with soda + benzidamine + honey (HG). | November 2011–January 2013. | Slightly greater relief in HG during the entire follow-up (3 months), with a significant reduction in the severity of OM-associated pain and fewer treatment interruptions. |

| Matsuda et al. (2015) [57] | 90 | Double-blind phase III RCT. | To research whether TJ-14 (Hangeshashinto) prevents and/or controls CT-induced OM in patients with colorectal cancer. | TJ-14 treatment group (IG); Placebo group (PG); WHO scale. | 0.5 (14 days). | Significant reduction in the duration of severe OM, with no effect on the severity or incidence of OM itself. |

| Bateman et al. (2013) [58] | Not specified (approximate number = 48). | Laboratory in vivo study | To investigate the protective effects of nutritional drinks on the development of methotrexate (MTX)-induced gastrointestinal mucositis in animals with and without cancer. | G1: ClinutrenProtect ® (whey protein, short-chain fatty acids, TGF-b, L-glutamine); G2: IMPACT AdvancedRecovery ® (whey protein, medium chain fatty acids, arginine, nucleotides, and polyunsaturated fatty acids); G3: placebo (drink); Control: standard rat diet. | Not specified. | Administered diets offered no observed protection against MTX-induced mucositis. |

| Jayachandran and Balaji (2012) [59] | 60 | RCT | To evaluate the effect of natural honey and benzidamine hydrochloride on the development and severity of RT-associated OM in patients with oral cancers. | 3 groups (oral rinses): (1) Honey (HG); (2) Benzidamine hydrochloride (BG); (3) Saline 0.9% (control group, CG). | 6 | Lower severity and earlier healing of OM not significant in HG. |

| Sugita et al. (2012) [60] | 118 | Retrospective CT | To ascertain the effects of folinic acid administration (systemic and rinsed) on the incidence of OM and acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) after GVHD prophylaxis with MTX in patients undergoing HSCT. | Systemic folic acid was administered to patients at increased risk of developing OM (n = 29). | 48 | Folinic acid could be useful in reducing the incidence of severe OM, both in systemic use and rinsed. |

| Sorensen et al. (2008) [61] | 206 | Double-blind RCT | To evaluate prevention of OM using chlorhexidine compared with cryotherapy during 5-FU CT in gastrointestinal cancer. | 3 groups: (1) Chlorhexidine rinse (IG); (2) Placebo rinse (saline) (PG); (3) Cryotherapy (CG). | - | Higher severity rate of OM in PG and lower in CG, with a lower incidence and duration in IG and CG than in PG; therefore, prophylaxis seems effective in both IG and CG. |

| Das et al. (2011) [62] | 52 | RCT | Observe protective/healing effect against RT and CT effects (OM, skin reaction, xerostomia, or voice changes) when using Glycyrrhiza glabra. | 4 groups: (1) Glycyrrhiza + local honey and oral Glycyrrhiza (GLHG); (2) Glycyrrhiza + local honey (LHG); (3) Topical honey (HG); (4) Control (conventional modern medication) (CG). | 1.75 (7 weeks) | Lower incidence and severity in GLHG and LHG compared with CG, but similar to HG. |

| Thornley et al. (2004) [63] | 37 | CT | To determine the feasibility and potential efficacy of a fixed combination of agents in reducing RRT (regimen-related toxicity) in children undergoing HSCT. | Combination group of ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), vitamin E, folinic acid, and titrated parenteral nutrition (IG); Historical control group (1995–2000) (PG). | 36 | Significant decrease in the incidence and severity of OM in IG. |

| Iyama et al. (2014) [64] | 44 | RCT | To research whether supplementation with GFO (glutamine, fibre, oligosaccharides) decreases the severity of mucosal injury post-HSCT. | GFO group (IG); Control (CG); CTCAE 4.0 version. | 36 | Significant decrease in OM and higher survival rate in IG. |

| Takano et al. (2015) [65] | 96-well plates | In vitro study | To investigate whether γ-tocotrienol (vitamin E) can enhance survival of oral human keratinocytes (RT7) against 5-FU-induced cell toxicity. | RT7 cells were treated with 5-FU and γ-tocotrienol. 4 groups: (1) γ-tocotrienol; (2) 5-FU; (3) γ-tocotrienol + 5-FU; (4) Control de 5-FU + N-acetylcysteine. | - | In C there was a significant inhibition of ROS production induced by 5-FU. |

| Agha-Hosseini et al. (2021) [66] | 59 | Triple-blind RCT | To evaluate whether a vitamin E, hyaluronic acid, and triamcinolone mouthwash was effective in the treatment of radiotherapy-induced OM grades 3–4. | Group with vitamin E + hyaluronic acid + triamcinolone rinses (IG); Group with triamcinolone rinses (CG). WHO scale | 4 weeks | Significant reduction in the severity of RT-induced OM in IG over time. |

| Yeshurun et al. (2020) [67] | 52 | Multicentre double blind RCT | To determine whether folinic acid (FA) reduces methotrexate (MTX)-induced toxicity in patients undergoing myeloablative conditioning (CM) for allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation, who have also received MTX prophylaxis for graft-versus-host disease. | TG with FA; PG with placebo; WHO scale. | 17 (4.5–50) | There were no significant TG and PG differences in incidence, duration, or severity of OM. |

| Pattanakitsakul et al. (2020) [68] | 30 | Preliminary and single-centre quasi-randomized trial | To examine the protective effect of vitamin A supplementation against mucosal damage of the gastrointestinal tract after CT in paediatric patients undergoing HSCT. As a secondary objective, to assess the occurrence of OM. | TG with single dose (200000 IU) of vitamin A; PG without vitamin A; WHO scale. | 12 | There were no significant differences in incidence or severity of OM. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Gozalbo, B.; Cabañas-Alite, L. A Narrative Review about Nutritional Management and Prevention of Oral Mucositis in Haematology and Oncology Cancer Patients Undergoing Antineoplastic Treatments. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4075. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13114075

García-Gozalbo B, Cabañas-Alite L. A Narrative Review about Nutritional Management and Prevention of Oral Mucositis in Haematology and Oncology Cancer Patients Undergoing Antineoplastic Treatments. Nutrients. 2021; 13(11):4075. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13114075

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Gozalbo, Balma, and Luis Cabañas-Alite. 2021. "A Narrative Review about Nutritional Management and Prevention of Oral Mucositis in Haematology and Oncology Cancer Patients Undergoing Antineoplastic Treatments" Nutrients 13, no. 11: 4075. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13114075

APA StyleGarcía-Gozalbo, B., & Cabañas-Alite, L. (2021). A Narrative Review about Nutritional Management and Prevention of Oral Mucositis in Haematology and Oncology Cancer Patients Undergoing Antineoplastic Treatments. Nutrients, 13(11), 4075. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13114075