Abstract

Promoting healthy eating habits can prevent adolescent obesity in which family may play a significant role. This review synthesized findings from qualitative studies to identify family barriers and facilitators of adolescent healthy eating in terms of knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP). A literature search of four databases was completed on 31 July 2020; qualitative studies that explored family factors of adolescent (aged 10 to 19 years) eating habits were included. A total of 48 studies were identified, with the majority being from North America and sampled from a single source. Ten themes on how family influences adolescent dietary KAP were found: Knowledge—(1) parental education, (2) parenting style, and (3) family illness experience; Attitudes—(4) family health, (5) cultivation of preference, and (6) family motivation; Practices—(7) home meals and food availability, (8) time and cost, (9) parenting style, and (10) parental practical knowledge and attitudes. This review highlights five parental characteristics underlying food parenting practices which affect adolescents’ KAP on healthy eating. Adolescents with working parents and who are living in low-income families are more vulnerable to unhealthy eating. There is a need to explore cultural-specific family influences on adolescents’ KAP, especially regarding attitudes and food choices in Asian families.

1. Introduction

There is strong evidence that obesity in childhood, particularly during adolescence, increases the risk of cardiovascular diseases [1,2], which are one of the most preventable causes of mortality worldwide [3]. The prevalence of adolescent obesity is rising rapidly across Asia, creating a major public health problem [4,5]. The high proportion of adolescents failing to meet dietary recommendations [6,7,8] calls for an exploration of the factors that influence the development of their eating habits.

The Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices (KAP) model is commonly applied in health education. This model emphasizes that the acquisition of knowledge is the foundation of beliefs and attitudes that reinforce the intention to adopt healthy behaviors [9]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the use of the model to help identify knowledge gaps, cultural beliefs, and behavior patterns [9] in order to inform the design of effective interventions for behavior change [10]. Indeed, two studies using the KAP model found that high school students in Korea had worse dietary habits than Chinese students despite acquiring more nutritional knowledge [11,12], suggesting a translation gap from knowledge to practice. Furthermore, a recent national study of 697 Chinese adolescents (aged 12 to 17 years) showed that nutritional knowledge and social attitudes were among the major predictors for food preferences [13].

To better understand how attitudes influence eating habits, a range of theories have been applied, including the Health Belief Model, Social Cognitive Theory, and Theory of Planned Behavior [14,15,16]. These theories emphasize the role of individual perception and social influence in determining eating behavior. The most relevant concepts include: (A) Outcome Expectation (or perceived benefits) on personal health relevance [17]; (B) Self-efficacy (or perceived power) on preference towards food and preparation time [17,18]; (C) Subjective Norms from family and peers [18,19]; (D) Cues to Action from media, and the home and school environment [19]. These concepts emphasize how a person’s intention to adopt a behavior is based on cognitive and motivational beliefs, i.e., attitudes [10]. Ecological models have also been used to examine how the environment impacts eating behaviors [15], highlighting the importance of socioeconomic status, including education level and household income, community, and household food environment as external correlations of eating practices.

Indeed, the significance of food parenting practices in shaping adolescent eating habits is featured in various behavior change models. The content map by Vaughn et al. categorized food parenting practices under three constructs—coercive control, structure, and autonomy support [20]. Except for those who exert coercive control, parents who respond to adolescents’ views by supporting them structurally and autonomically will influence the social and cognitive determinants of their child’s healthy eating habits. Specifically, adolescents perceive the structure of rules and limits as well as parental modeling of dietary patterns, either healthy or not, as Subjective Norms. Furthermore, the structure of food availability at home, meal preparation, and snack times can promote Cues to Action. Autonomy support can be provided by nutrition education, child involvement, and encouragement, all of which will enhance their Outcome Expectation and Self-efficacy.

Although the influence of parental food practices has been investigated, Vaughn et al. identified a lack of research around the family, parent, and child characteristics underlying the use of these practices as well as the non-linear and indirect impact on child eating practices [20]. Indeed, certain parenting practices may be explained by latent parental characteristics, such as parenting style and knowledge [21,22,23]. Furthermore, it is important to note that parenting practices do not only affect the current eating habits of children but also influence how children choose their own food in the long term [20]. In this regard, studies should examine the impact of parent characteristics and parenting practices, collectively termed as family factors, on the cognition of adolescents (i.e., knowledge and attitudes that influence healthy eating practices).

Several systematic reviews of quantitative studies have explored how family factors influence eating habits among adolescents in terms of food accessibility, parental modeling, and guidance [24,25,26]. Although we know “what” family factors affect adolescent eating habits, it is not entirely clear “how” and “why” they are, or are not, able to support adolescents in adopting healthy eating practices. Qualitative studies can provide more in-depth insights into the perspectives, experiences, and attitudes that explain quantitative research findings [27]. For example, reviews by a research team in Denmark found that quantitative [28] and qualitative [29] studies complemented each other during an investigation of the determinants of fruit and vegetable intake by 6- to 18-year-olds. For example, the review of quantitative data identified socioeconomic position, parental intake, and home availability/accessibility as being positively associated with fruit and vegetable consumption (n = 98 studies) [28]; whereas time, cost, and several knowledge-related factors (i.e., preparation methods and short-term outcome expectations) were revealed only in the review of qualitative studies (n = 31) [29].

To address the research question “How does the family influence adolescent eating habits in terms of knowledge, attitudes, and practices?”, we carried out a systematic review of qualitative studies to summarize existing knowledge on family barriers and facilitators of adolescent healthy eating in terms of knowledge, attitudes, and practices, in order to identify the common family factors and any culture or social specific factors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

An electronic systematic search of the following four databases, from the year of their inception to 31 July 2020, was performed: PubMed, Web of Science, PsycINFO, and Embase. These databases covered the disciplines of life sciences, medicine, and behavioral and social sciences. References of the included papers were examined for inclusion in order to capture additional relevant articles.

The search terms were developed following the PICO framework [30] of population (adolescents and family), intervention (knowledge, attitudes, and practices), comparison (not applicable), and outcome (eating habits), which was supplemented with study design (types of qualitative data collection and analysis) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Literature search terms.

2.2. Study Selection

Articles published in English were included if they: (1) targeted healthy adolescents aged 10 to 19, determined by age range or mean age, and/or their parents/caregivers, (2) identified family factors that influence adolescent’s KAP of eating habits, and (3) applied qualitative data collection and analysis. Studies involving populations of different age groups were included only if findings specific to adolescents were described. Opinions from people other than family members, such as teachers and professionals, were included if they were relevant to family influences.

Studies were excluded if they (1) targeted adolescent groups with specific health problems (e.g., being overweight or having an eating disorder), (2) evaluated the impact of health promotion activities, such as nutrition workshops or mobile application on eating habits, (3) combined results from both quantitative and qualitative research methods, or (4) were reviews or conference abstracts.

Two reviewers independently assessed each identified article for inclusion, first based on the title and abstract, followed by an in-depth review on the full text. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were discussed to reach consensus and the first author (K.S.N.L.) further reviewed the unresolved articles.

2.3. Data Extraction

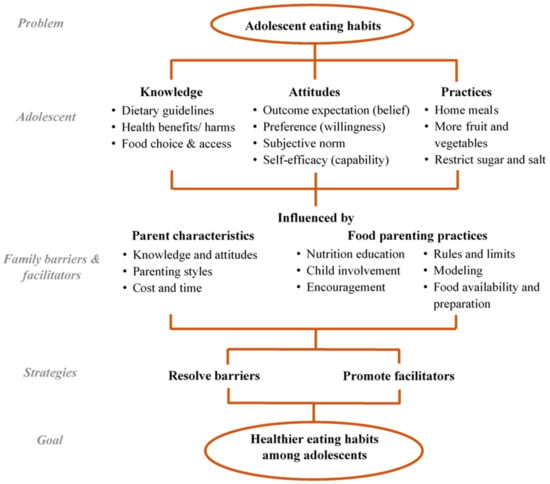

A data extraction excel spreadsheet was developed to systematically record all relevant data, including (1) country of origin, (2) aim(s), (3) research design, (4) sample characteristics, (5) phenomenon of interest, (6) key themes/theoretical framework, (7) major findings in KAP, and (8) conclusions. The KAP framework shown in Figure 1 was used to guide data extraction from the “Results” section of each study. The framework incorporated the key concepts of the social cognitive theories in the Attitudes construct. Parent characteristics and food parenting practices described in the content map by Vaughn et al. are the potential themes of barriers and facilitators [20]. The findings were categorized into family barriers or facilitators according to the perception of the informants. Data extraction was performed by two reviewers independently and any disagreement was resolved by a third party (K.S.N.L.).

Figure 1.

Theoretical Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices framework for data extraction on family factors.

2.4. Quality Assessment

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist for qualitative studies was adopted to systematically evaluate the quality of the selected studies [31]. The checklist covered the assessment in 10 aspects, including: (1) clear statement of research aim, (2) appropriateness of qualitative research, (3) research design, (4) subject recruitment, (5) data collection methods, (6) researcher bias, (7) research ethics, (8) rigor of analysis, (9) discussion of findings, and (10) study implications. Each aspect is scored 0, 1, or 2 to denote “not complied”, “cannot tell”, and “complied”, respectively. The summation of the 10 sub-scores results in a maximum quality score of 20.

2.5. Data Synthesis

The findings of selected studies were first categorized according to the theoretical KAP framework shown in Figure 1. The themes on family barriers and facilitators were either deduced from the KAP framework or induced from the findings (e.g., family illness experience and cultivation of preference) by the research team. The themes were further summarized by constant comparative analysis [32], an iterative procedure to identify common or inconsistent findings across studies. Country of origin, subject characteristics (e.g., age of adolescents, type of informant), and other contextual factors of the studies were examined to identify possible reasons for inconsistent findings.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Study Characteristics

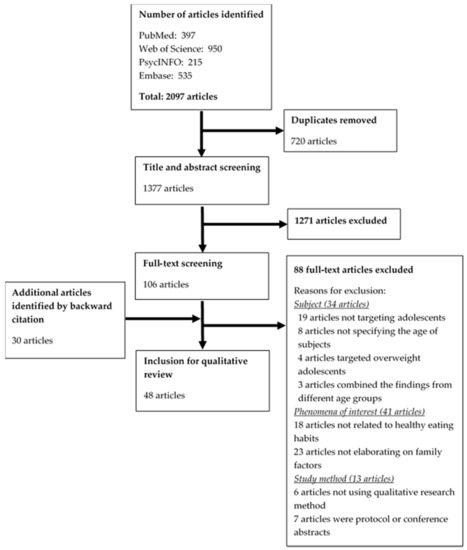

A total of 2097 articles were identified from the four databases. Among the 42 articles remaining after full-text review, 6 additional articles were included following backward citation. This resulted in a final total of 48 articles from unidentical studies being included in this review. Figure 2 shows the PRISMA flow diagram on study selection. The majority of studies (n = 37) were published between 2010 and 2020, with the earliest article published in 2000. The studies were mainly conducted in the Americas (n = 31), with smaller numbers conducted in Asia (n = 7), Europe (n = 6), Africa (n = 2), and Australia (n = 1). One study was multi-national (India and Canada). Two of the Asian studies were local studies on Chinese families in Hong Kong [33,34]. Twenty-one studies interviewed multiple sources including adolescents, parents, and/or family members; fifteen of them interviewed parent-adolescent dyads from the same family; only three studies conducted the dyad interviews in the same setting [35,36,37]. Four studies targeted older adolescents aged 15 to 19 [38,39,40,41]. Study characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram on study selection.

Table 2.

Summary table of reviewed studies.

3.2. Study Quality

The quality scores of the forty-eight reviewed studies ranged from 13 to 20 with an average of 17.8, out of a maximum of 20. Among them, 19 studies had a high quality score of 19 or above, 24 had a moderate quality score of 16 to 18, and the remaining 5 studies had a low quality score of 13 to 15 (Table 3). The studies complied with an average of 8 aspects (out of 10), ranging from 3 in one study to 10 in seven studies. All studies had a clear statement of research aim and appropriateness of qualitative research; most studies satisfied the criteria on study implications, rigor of analysis, and discussion of findings. Conversely, there was insufficient discussion on researcher bias and research design in 33 and 18 studies, respectively. The study by O’Dougherty et al. had the lowest quality score of 13 and the lowest compliance rate of only three aspects [64]; it was included in the review as the findings were consistent with other studies.

Table 3.

Quality assessment of reviewed studies (2 = Complied, 1 = Cannot tell, 0 = Not complied).

3.3. Synthesis of Findings

The family factors can be categorized into 10 themes under the adolescent dietary KAP framework: Knowledge—(1) nutrition education, (2) child involvement, and (3) family illness experience; Attitudes—(4) family health, (5) cultivation of preference, and (6) family motivation; Practices—(7) food preparation and availability, (8) time and cost, (9) parenting style, and (10) parental practical knowledge and attitudes. Table 4 summarizes the findings (refer to Supplementary Materials Table S1 for detailed findings extracted from each article).

Table 4.

Summary of findings by themes.

3.3.1. Adolescent Knowledge

There are, broadly, two types of dietary knowledge: theoretical knowledge and practical knowledge. Theoretical knowledge refers to the understanding of “why” and “what is” healthy eating, which includes health benefits and consequences of different eating habits and the recommended dietary intake. Practical knowledge refers to understanding “how” to eat healthily, from food selection during grocery shopping to cooking skills in meal preparation.

- Nutrition education (theme 1)

- Many studies found nutrition education by parents on both types of knowledge is a facilitator for adolescents to eat healthily, specifically, education on nutrition benefits. For example, disease prevention, weight loss and growth [38,43,51,56,66,67,70,74,77,80], health consequences of unhealthy eating such as heart and kidney problems [33,44,47,55], and healthy food choice and cooking skills [38,39,43,44,48,55,56,57,58,61,66,70,71,77,80]. However, parents with inaccurate knowledge can deliver messages that are inconsistent with what is taught at school, which confuses the adolescents [55].

- Child involvement (theme 2)

- Communication between parents and adolescents is important in education [37,47,54], whereas child involvement in meal planning and discussion facilitates effective communication. Four parenting strategies were identified: (1) mealtime and grocery shopping being used as opportunities to teach adolescents nutritional knowledge, such as reading food labels [38,51,55,65,66,71,80]; (2) open discussion on diet-related health outcomes [39,47]; (3) teaching adolescents about self-regulation [55,66]; (4) providing nutritional information in a casual and fun way [37]. Conversely, excluding adolescents from grocery shopping and meal preparation due to their busy study schedules served as a barrier to adolescents’ acquisition of practical nutritional knowledge [39]. Parents also perceived that the ability of food discussion was limited by their own poor eating habits [51].

- Family illness experience (theme 3)

- Illness experience of family members was perceived to facilitate the education of adolescents on the consequences of unhealthy eating in three US studies [44,47,55]. However, discussion on food and health was perceived as a taboo in some families [39].

3.3.2. Adolescent Attitudes

Attitudes towards healthy eating were categorized into four domains: (i) outcome expectation: the belief in and the perceived importance of health outcomes resulting from eating habits; (ii) preference: the liking of certain food groups or eating habits, which includes preference for taste, fun, and health; (iii) subjective norm: expectation of significant others, such as family, peers, and teachers, by role modeling and encouragement; (iv) self-efficacy: the capability to achieve certain behavior, predominantly influenced by practical knowledge and barriers.

- Family health (theme 4)

- Adolescents have become more aware of the negative impacts of unhealthy eating from the experience of health problems, particularly obesity, diabetes mellitus, and heart diseases, among the family members in the US studies [37,39,47,54]. Belief in healthy eating was, on the other hand, enhanced by observing positive outcomes from family members consuming healthy foods such as fruit and vegetables [35,69].

- Cultivation of preference (theme 5)

- Cultivating preference for healthy food was a commonly found family facilitator, particularly in studies where participants were young adolescents [35,37,43,51,58,59,62,64,65,66,70]. Communication on nutritional information influenced their food interpretation and preference for health [37,51,59]. Parents could broaden adolescents’ taste preferences and acceptance by exposing them to a wide variety of nutritious foods at an early age [43,65,70] and by making healthy eating fun, for example, choosing vegetables in certain colors during shopping [35] as well as providing fewer food choices at home [64]. To tackle the taste preference for junk food, parents tried to reduce these temptations by limiting sedentary time and engaging their adolescents in activities such as sports and hobbies [43]. Hygienic concerns could encourage adolescents, particularly in rural areas, to eat at home instead of food stalls on the streets [60]. One barrier hindering adolescents’ preference for healthy food was family’s prioritizing either low cost or unhealthy food [40,51].

- Family motivation (theme 6)

- Family norm and role modeling can be both facilitators of and barriers to healthy eating in adolescents. Aside from listening to their parents’ advice, adolescents also choose their food by observing their parents’ and siblings’ eating habits of both healthy [35,37,43,44,47,55,56,57,59,66,68,70,77,80] and unhealthy foods [39,40,46,47,48,49,50,54,59,68,69,72,73,74,79]. Parents who followed the same rules as they told their children enhanced the formation of the family norm [56,80]. Parents’ verbal encouragement and compliments served as positive reinforcement for healthy eating habits [35,38,44,49,51,68,69,71,75,77]. Examples include setting expectations on diet [51,80], family support on trying healthy foods for the first time [35], making healthy eating their family lifestyle [35], describing the taste of healthy foods [66], and communication between parents regarding adolescent eating habits [80]. Parental encouragement could be initiated by their concerns around adolescents’ health, in particular weight gain and illnesses from eating unhealthy foods [57,66], which formed the subjective norm in their children [38,56,78].

In addition to family members’ preference for unhealthy foods [40,46,72], another important family barrier that impedes healthy eating was not prioritizing health in the family [42,50,51]. Some parents had cultural beliefs suggesting that thinness is a sign of sickness and convinced adolescents that body weight is not an important indicator of health [42,78], while some considered food choice was adolescents’ own responsibility, hence not providing sufficient guidance on healthy eating [42,79]. The busy schedule of working parents limited their chances to talk to their children and therefore made it difficult to encourage healthy eating among adolescents [75]. Nevertheless, two studies on low-income families found that the unhealthy eating habits in parents motivated some adolescents to eat healthily in order to be the role models for the family [77,78].

3.3.3. Adolescent Practices

Practices of healthy eating refer to the consumption of fresher products such as fruit and vegetables, and less junk food with high sugar or salt content, such as sugary drinks, confectionaries, and chips. Mealtime is the major food occasion, and any food consumption between meals or after dinner is defined as snacking.

- Food preparation and availability (theme 7)

- Many studies identified home meals as an important facilitator of healthy eating [33,34,35,36,38,42,43,44,48,50,61,62,63,66,70,71,75,77,78,80]. Subjects regarded food prepared at home as healthy due to better variety, freshness, and reduced uses of sugar, oil, and salt [33,71,78]. Apart from home meals, food availability also influenced adolescent food choice at home. Parents could manage the food supply to provide more healthy foods and to restrict food with insufficient nutrients [36,37,39,40,42,43,44,45,47,48,49,50,52,55,56,57,59,60,61,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,73,74,77,79,80]. Failure of some families to provide healthy meals [39,54,63,76,78] or stock healthy foods at home [40,41,46,48,49,53,59,67,68,69,74,78] is explained in more depth in the following themes.

- Time and cost (theme 8)

- Time and cost for healthy food were important barriers to healthy food provision at home. A tight schedule and long working hours of parents prevented them from preparing family meals, encouraging adolescents to consume takeaway, fast, and prepackaged food instead of fresh foods [35,36,37,41,43,45,48,50,52,53,54,59,61,63,64,65,68,69,70,71,76,78,79,80]. Some adolescents explained that more preparation work such as washing, cutting, and cooking is required for fresh production, as compared to ready-to-eat junk food and sugary drinks [40,67,69]. Easy accessibility of restaurants and food shops further attracted families to eat unhealthy food through takeaway or when they were eating out [36,72]. Peeling fruit and vegetables as well as cutting them into ready-to-eat pieces can overcome the ‘inconvenience’ barrier, especially among young adolescents [49,56,67,69,80]. Preparing portable water in the refrigerator provided a healthier alternative to sugary drinks on hand [57,66,73], while keeping snacks in a locked cabinet restricted the accessibility to young adolescents [64].

- Although low food budget might limit the purchase of junk snacks in some Western studies [36,59,66,79], it was also an important barrier to the purchase of more costly healthy food such as fruit, vegetables, and organic products, especially among low-income families who might choose unhealthy high-energy food because of its lower cost [34,35,36,37,38,41,45,46,48,49,51,54,60,61,66,67,69,72,75,77,78,79,80].

- Parenting style (theme 9)

- Several key parenting practices were highlighted in various studies, which could be facilitating or inhibiting adolescents’ eating habits, depending on the parenting styles. Setting family rules facilitated healthy eating in adolescents during home meals and snacking. Some examples of rules include: having vegetables with every dinner, finishing everything on the plate, and serving the same meal to all family members [37,44,49,52,53,61,63,77], as well as restricting the consumption of unhealthy snacks in terms of quantity and frequency, and drinking water between glasses of juice [33,37,42,43,47,50,52,56,59,64,67,68,77,80]. Some parents further monitored their adolescents’ eating practices by verbally checking on food purchases or consumption [49,56,80], tracking food stock at home [56], and requesting adolescents to seek permission before eating unhealthy food [67]. Several authoritative parenting strategies were proposed: (i) controlling or providing supervision on food choices such as asking adolescents to at least try a few bites of healthy food [44,48,49,69,74,75]; (ii) encouraging or prompting adolescents to try healthier alternatives with reasoning [37,57,60,66,70]; (iii) having regular meal schedules and eating with family [35,52,55,71]; (iv) setting a snacking allowance [43,64]; (v) being responsive to adolescents’ preference, especially on nutritious foods [64,80]. Except for one Canadian study that found parents preferred grocery shopping alone to prevent requests for junk foods by adolescents [44], involving them in meal planning, shopping and preparation with limited/ guided choices, such as selecting from a list of food choices, and washing and cutting fresh produce [37,44,59,64,80], was perceived as a facilitator to their eating habits.

- Unstructured practices are a major barrier to healthy eating practices in adolescents. Accommodating taste preference of family members, usually towards fast food [37,42,64,68,78], a lack of monitoring when not eating together at a table [66], and failing to negotiate for healthy eating [79] could counteract the benefits of home meals. The lack of parental supervision also encouraged adolescents’ unhealthy snacking habits as their food choice tended to be based on taste preferences and minimal preparation effort [39,40,50,51,53,59,66,67,69,72,76,79,80]. Family members, especially grandparents, might provide adolescents with unhealthy foods as treats and bribes [36,50], and these items such as chocolates, candies, and pizza were often used as rewards for good academic performance, helping out with chores, or even eating healthy foods [53,59,66,67,72,80]. On the other hand, over-restriction could have an opposite effect on adolescents as they might want the restricted food items more and consume them on other occasions when they are not monitored [70,80]. Some adolescents with poor family relationships mentioned that the unpleasant atmosphere of eating with their family sometimes prevented them from eating at home [63].

- Parental practical knowledge and attitudes (theme 10)

- The perception of home meals as inferior in taste with little variation [60,62,63] could be the result of insufficient knowledge on the range of healthy food choices and inadequate skills to prepare tasty, healthy meals. To facilitate healthy eating at home, some parents highlighted the importance of cooking skills to better the presentation of healthy food, for example, hiding fruit and vegetables in soup, stew, or smoothies [43,59,66,67,80], while others would modify recipes, attempting to use healthier cooking methods, optimizing food choices, and preparing meals at lower costs [36,72]. A number of US studies reported that a high level of health awareness in parents was essential to maintaining a healthy food environment at home [40,51,58,59,63].

Parents lack of nutritional knowledge, or concern, were barriers to providing healthy meals for adolescents [34,40,50,54,71,72,77]. Disagreement on the interpretation of nutrition guidelines, such as the perceived definition of a serving among different family members [37], was an additional barrier to a healthy home food environment.

4. Discussion

4.1. Major Findings

This review of 48 qualitative studies confirmed the findings of earlier reviews on the importance of parental education, role modeling, and home food environment on adolescent eating habits [24,25,26,29], and explained how these factors influence the KAP of adolescents. In recent years (2016–2020), an increasing number of studies have explored how family facilitates healthy eating through education on health benefits, fostering cooking skills, and food discussion during mealtimes. This may be the result of more awareness of healthy eating worldwide following the launch of the 2013 Global Action Plan against non-communicable diseases by the WHO [81].

Furthermore, we found that food parenting practices described in Vaughn et al.’s content map are multifactorial and co-constructed in the family through the KAP of different members and family relationships. In particular, this review identified five parental characteristics—parental knowledge, attitudes, parenting style, time, and cost concern—as the underlying facilitators of or barriers to food parenting practices that influence adolescents’ KAP on healthy eating.

4.1.1. Parental Knowledge

Parents use their knowledge to provide their children with guidance on healthy eating. Indeed, such knowledge enables parents to prepare tasty and healthy meals of varied presentation, cooking methods, and with a wide range of ingredients. These may confer further benefits by cultivating a wider taste preference and better diet quality in children, as shown in previous interventions on empowering cooking skills in parents [82,83,84].

4.1.2. Parental Attitudes

Parental concern in family health facilitates motivation and provision of quality meals to adolescents. While its facilitating role is presented in this review [38,56,57,66,78], the low priority of adolescent health among parents is also revealed [42,50,78]. As proposed in a previous narrative review [85], fathers are less conscious of encouraging adolescents to eat healthily, and tend to abdicate the responsibility to their spouses, who are the primary caregivers in the family. An additional explanation is that parents are afraid of raising issues around body weight as they believe it could cause their children undue psychological stress [86]. Alternatively, some parents might perceive the increased obligations their adolescents take up from schoolwork, extracurricular activities, and social relationships with peers as more important than adolescent health. These attitudes reduce the tendency of parents to enhance dietary KAP in adolescents. Changing parents’ misconception of ‘health is less important than schoolwork’ and educating parents that a healthy diet is beneficial to school performance [87,88,89,90] can be a solution.

4.1.3. Parenting Style

There is a spectrum of parenting styles, ranging from authoritarian, to authoritative, to permissive. It is a consistent finding that an authoritative parenting style (i.e., being involved with reasonable expectations) facilitates adolescents’ KAP of healthy eating—providing nutrition information in a friendly and open manner, cultivating adolescent preference for healthy eating, and controlling their food consumption by rules and monitoring—whereas the two extremes do not. Parents may encounter challenges in parenting as their children grow, especially when social impacts from peers, teachers, and media become increasingly influential, and parents are being viewed as less powerful and ideal [91]. Therefore, involving adolescents in food preparation can be a strategy to facilitate communication and exchange of knowledge and attitudes, in addition to its positive association with diet quality [92,93,94].

4.1.4. Lack of Time

The competing demands from work and studies may limit the time available for families to practice healthy eating. Working mothers in Germany and the US were found to spend less time in meal preparation, eating with adolescents, and encouraging healthy eating than their non-employed or part-time counterparts [95,96]. Furthermore, the longer the length of parents’ working hours, the higher the tendency for young adolescents to have unhealthy family meals [97,98], which was reflected in this review, emphasizing that working parents preferred fast and prepackaged food instead of preparing a home meal after work.

4.1.5. Cost Concern

The cost of food is another important family barrier that can impact healthy food choices. This review consistently found that many parents choose unhealthy high-energy foods for their low cost, particularly parents from low-income families. The positive relationship of socioeconomic status and diet quality is well known in the literature [99,100], where the trade-off between food cost, food waste, and health is a common dilemma [101]. One study in our review found that discussion on food choices in low SES families was understandably focused on the price of food as opposed to healthy eating and food quality [51], which may encourage adolescents to choose unhealthy food due to its lower cost. This could potentially impede their ability for behavioral change in the future.

4.1.6. Effect of Study Population and Design on Results

The inclusion of studies from different cultures and informant perspectives enriched our understanding of the complex family influence on adolescent eating habits. We have identified family factors that were common to a wide spectrum of studies as well as family factors that were specific to certain cultural and demographic backgrounds.

The studies in this review had similar findings on parental roles in adolescents’ eating habits, although the discussion on family influences on adolescents’ attitudes was less comprehensive in the studies conducted in Asia. For example, whether Asian parents perceive adolescent health as important is yet to be explored. The facilitating role of family illness experiences on the knowledge and outcome expectation in adolescents was only discussed in some US studies. This may be due to the higher prevalence of obesity and non-communicable disease in the US [102,103].

Studies involving both parents and adolescents had more discussion on family facilitators, especially on adolescents’ dietary attitudes. For example, parent–adolescent dyads in two studies suggested family facilitators not seen in research involving only the parents or the adolescents, such as parents demonstrating the benefits of healthy eating [35], making healthy eating fun and a family lifestyle [35], and acquiring the habits through ongoing family discussion on healthy eating [37]. These illustrate that interviewing parent–adolescent dyads may enable a more in-depth exploration on the dyadic mutual influences in constructing eating habits.

The studies on young adolescents and their parents identified facilitators related to parenting such as family rules, parental monitoring, and parental effort in ensuring food accessibility. Conversely, studies on older adolescents mainly discussed family barriers in terms of home availability of unhealthy food and parents’ lack of time and monitoring. This may be due to the increased autonomy in adolescents and the change in the amount of parenting time. For example, a US population-based study found a decrease in parenting time from 1999 to 2004 and a transitional decrease from early to late adolescence [104]. This reflects that the time barrier becoming more common as more mothers work full-time, especially when their children grow older. Parents should be aware of how parenting time in monitoring, guiding, and providing healthy food and meals remains important in shaping adolescents’ eating habits.

4.2. Implications of Findings

This review demonstrates the applicability of the KAP framework in exploring familial influences on adolescents’ eating habits. It identifies the interactive effect of parental knowledge, attitudes, parenting style, and time on dietary KAP in adolescents. Some less well-recognized family factors, such as unbalanced diet due to wrong interpretation of guidelines and cultivation of food preference for health, were also explored.

Our review supports the importance of authoritative parenting and parental health concern in facilitating the development of healthy eating habits in adolescents. This counteracts the trend of adopting a permissive parenting style and a pre-mature independence of adolescents in their food choices.

Adolescents with working parents and who are living in low-income families are more vulnerable to unhealthy eating habits due to insufficient knowledge, health awareness, parenting time, and cost concern. There is a need to enhance dietary knowledge and attitudes among parents and to explore time- and cost-saving strategies of healthy eating for these vulnerable families.

4.3. Gaps in the Existing Knowledge

We found a disproportionately small number of studies from Asia, despite the fact that 60% of the world’s population lives in this region. Among these studies, only two targeted Chinese adolescents, both of which were from Hong Kong and interviewed only adolescents with no data from their parents. This may lead to an insufficient discussion on parental perspectives, for example, the relative importance of adolescent health among other competing concerns. This may be most relevant in Hong Kong and other Asian populations where academic achievement is greatly emphasized in the parenting culture [105] and school children are heavily burdened by academic work [106]. The relationship between how Chinese families trade off academic demands and healthy eating in their adolescents is yet to be explored.

Moreover, studies collecting perspectives from parent–adolescent dyads in the same interview are also limited to only three and none of them were on Asian populations. Dyadic interviewing enables the observation of family dynamics and how the dyads co-construct dietary KAP [107], especially parental effort in cultivating positive attitudes towards healthy eating in adolescents.

Finally, the KAP model has rarely been adopted to study family influences. Although a few studies explored adolescents’ KAP of healthy eating [37,38,61,69], none of them identified specific family influences on each of the KAP constructs. Future qualitative studies implementing the KAP model may provide additional insights on how family impacts adolescents’ knowledge of and attitudes towards healthy eating.

4.4. Study Limitations

The results of this review were limited by three methodological issues. First, the studies were contextually diverse in country of origin, source of data, and SES of subjects, which could lead to bias from cultural differences despite cross-validation of findings. In order to overcome this limitation, we compared study characteristics within each theme to identify potential discrepancies between studies conducted in different contexts and minimize the synthesis bias. Second, the majority of studies did not use the KAP framework and, therefore, the results were embedded among other themes without a clear categorization using the KAP constructs. The extraction and categorization of the study findings under the KAP constructs relied on subjective interpretation by the researchers; however, we believe the use of a pre-study thematic framework and two independent reviewers can assure the validity of the results. Last, since the search was limited to studies published in English, so as to enable accessibility and peer review, some relevant studies performed on Chinese families that are published in Chinese might have been excluded.

5. Conclusions

Using the KAP framework, this review found that authoritative parenting styles as well as parental dietary knowledge and attitudes are facilitators of food parenting practices that promote adolescents’ KAP of healthy eating, while time and cost concerns are major barriers. Studies that conducted interviews with parent–adolescent dyads provided richer data on the dyadic mutual influence, which should be encouraged in future studies. Adolescents with working parents and low SES may be more vulnerable to unhealthy eating habits as their parents may not have sufficient knowledge and time to educate them or to serve as role models, in addition to having a limited food budget. Time- and cost-saving strategies that promote healthy eating in adolescents deserve more investigation. There could be cultural differences in family influences on adolescents’ KAP, especially in the aspects of attitudes and food choices, which call for more studies among Asian families.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu13113717/s1, Table S1: Data extraction of reviewed studies.

Author Contributions

K.S.N.L., L.E.B. and C.L.K.L. formulated the research question and search strategies. K.S.N.L., M.Y.C.N. and M.H.Y.Y. performed screening, data extraction and quality assessment. K.S.N.L. and M.Y.C.N. drafted the manuscript. K.S.N.L., J.Y.C. and C.L.K.L. synthesized the findings. K.S.N.L., J.Y.C., M.Y.C.N., L.E.B. and C.L.K.L. finalized the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a research donation to the University of Hong Kong from the Kerry Group Kuok Foundation (Hong Kong) Limited (KGKF).

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Materials files.

Acknowledgments

It is acknowledged of the contribution of the research team including Sharon Fung on study screening, data extraction and quality assessment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Llewellyn, A.; Simmonds, M.C.; Owen, C.; Woolacott, N. Childhood obesity as a predictor of morbidity in adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2016, 17, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, A.; Twig, G. The Impact of Childhood and Adolescent Obesity on Cardiovascular Risk in Adulthood: A Systematic Review. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2018, 18, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Sun, H.; Ma, Y.; Han, D.; Pan, C.W.; Xu, Y. Prevalence and trends in obesity among China’s children and adolescents, 1985–2010. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105469. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Du, W.; Su, C.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, H.; Jia, X.; Huang, F.; Ouyang, Y.; et al. Prevalence and stabilizing trends in overweight and obesity among children and adolescents in China, 2011–2015. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, C.; Steer, T.; Maplethorpe, N.; Cox, L.; Meadows, S.; Nicholson, S.; Page, P.; Swan, G. National Diet and Nutrition Survey: Results from Years 7 and 8 (Combined); Department of Health and Social Care: London, UK, 2018.

- Batis, C.; Aburto, T.C.; Sánchez-Pimienta, T.G.; Pedraza, L.S.; Rivera, J.A. Adherence to Dietary Recommendations for Food Group Intakes Is Low in the Mexican Population. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 1897S–1906S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Health Protection. Report of Population Health Survey 2014/15; Department of Health, HKSAR: Hong Kong, China, 2017.

- World Health Organization. Advocacy, Communication and Social Mobilization for TB Control: A Guide to Developing Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Surveys; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Marías, Y.; Glasauer, P. Guidelines for Assessing Nutrition-Related Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hyun, H.; Lee, H.; Ro, Y.; Gray, H.L.; Song, K. Body image, weight management behavior, nutritional knowledge and dietary habits in high school boys in Korea and China. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 26, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Son, S.; Ro, Y.; Hyun, H.; Lee, H.; Song, K. A comparative study on dietary behavior, nutritional knowledge and life stress between Korean and Chinese female high school students. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2014, 8, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; He, J.; Fan, X. Mapping and Predicting Patterns of Chinese Adolescents’ Food Preferences. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshpande, S.; Basil, M.D.; Basil, D.Z. Factors Influencing Healthy Eating Habits among College Students: An Application of the Health Belief Model. Heal. Mark. Q. 2009, 26, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleddens, E.F.C.; Kroeze, W.; Kohl, L.F.M.; Bolten, L.M.; Velema, E.; Kaspers, P.J.; Brug, J.; Kremers, S.P.J. Determinants of dietary behavior among youth: An umbrella review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riebl, S.K.; Estabrooks, P.A.; Dunsmore, J.C.; Salva, J.; Frisard, M.I.; Dietrich, A.M.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Davy, B.M. A systematic literature review and meta-analysis: The Theory of Planned Behavior’s application to understand and predict nutrition-related behaviors in youth. Eat. Behav. 2015, 18, 160–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, L.; Hutchesson, M.J.; Rollo, M.E.; Morgan, P.J.; Collins, C.E. Motivators and Barriers to Engaging in Healthy Eating and Physical Activity. Am. J. Men Health 2017, 11, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dea, J.A. Why do kids eat healthful food? Perceived benefits of and barriers to healthful eating and physical activity among children and adolescents. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2003, 103, 497–501. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.L.; Iturralde, E.; Haya-Fisher, J.; Kim, S.; Keeton, V.; Fernandez, A. Barriers and facilitators to healthy eating among low-income Latino adolescents. Appetite 2019, 138, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughn, A.E.; Ward, D.S.; Fisher, J.O.; Faith, M.S.; Hughes, S.O.; Kremers, S.P.; Musher-Eizenman, D.R.; O’Connor, T.M.; Patrick, H.; Power, T.G. Fundamental constructs in food parenting practices: A content map to guide future research. Nutr. Rev. 2016, 74, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodenburg, G.; Kremers, S.P.; Oenema, A.; van de Mheen, D. Associations of parental feeding styles with child snacking behaviour and weight in the context of general parenting. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 960–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleddens, E.F.; Kremers, S.P.; Stafleu, A.; Dagnelie, P.C.; De Vries, N.K.; Thijs, C. Food parenting practices and child dietary behavior. Prospective relations and the moderating role of general parenting. Appetite 2014, 79, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J.; Dollman, J.; Petkov, J.; Parletta, N. Associations between parenting styles and nutrition knowledge and 2–5-year-old children’s fruit, vegetable and non-core food consumption. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 1979–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, J.; Harden, A.; Rees, R.; Brunton, G.; Garcia, J.; Oliver, S.; Oakley, A. Young people and healthy eating: A systematic review of research on barriers and facilitators. Health Educ. Res. 2006, 21, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, N.; Biddle, S.; Gorely, T. Family correlates of fruit and vegetable consumption in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yee, A.Z.H.; Lwin, M.O.; Ho, S.S. The influence of parental practices on child promotive and preventive food consumption behaviors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon-Woods, M.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Roberts, K. Including qualitative research in systematic reviews: Opportunities and problems. J. Evaluation Clin. Pract. 2001, 7, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, M.; Krølner, R.; Klepp, K.-I.; Lytle, L.; Brug, J.; Bere, E.; Due, P. Determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among children and adolescents: A review of the literature. Part I: Quantitative studies. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2006, 3, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krølner, R.; Rasmussen, M.; Brug, J.; Klepp, K.-I.; Wind, M.; Due, P. Determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among children and adolescents: A review of the literature. Part II: Qualitative studies. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methley, A.M.; Campbell, S.; Chew-Graham, C.; McNally, R.; Cheraghi-Sohi, S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist 2018. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Harden, A.; Garcia, J.; Oliver, S.; Rees, R.; Shepherd, J.; Brunton, G.; Oakley, A. Applying systematic review methods to studies of people’s views: An example from public health research. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2004, 58, 794–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.; Prendergast, G.; Grønhøj, A.; Bech-Larsen, T. Adolescents’ perceptions of healthy eating and communication about healthy eating. Health Educ. 2009, 109, 474–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, J.Y.-M.; Chan, K.; Lee, A. Adolescents from low-income families in Hong Kong and unhealthy eating behaviours: Implications for health and social care practitioners. Health Soc. Care Community 2019, 27, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berge, J.M.; Arikian, A.; Doherty, W.J.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Healthful Eating and Physical Activity in the Home Environment: Results from Multifamily Focus Groups. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2012, 44, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuster, M.; Weindorf, S.; Mateo, K.F.; Barata-Cavalcanti, O.; Leung, M.M. “It’s Sort Of, Like, in My Family’s Blood”: Exploring Latino Pre-adolescent Children and Their Parents’ Perceived Cultural Influences on Food Practices. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2019, 58, 620–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, M.; Kiernan, N.E.; James, L. Intergenerational Family Conversations and Decision Making about Eating Healthfully. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2006, 38, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banna, J.C.; Buchthal, O.V.; Delormier, T.; Creed-Kanashiro, H.M.; Penny, M.E. Influences on eating: A qualitative study of adolescents in a periurban area in Lima, Peru. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, C.A.; Rehm, M.; Coccia, C.; Cui, M. Adolescent Eating Behavior: The Role of Indulgent Parenting. Fam. Soc. J. Contemp. Soc. Serv. 2015, 96, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Avila, A.G.; Papadaki, A.; Jago, R. The role of the home environment in sugar-sweetened beverage intake among northern Mexican adolescents: A qualitative study. J. Public Health 2019, 27, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedibe, M.; Feeley, A.; Voorend, C.; Griffiths, P.; Doak, C.; Norris, S. Narratives of urban female adolescents in South Africa: Dietary and physical activity practices in an obesogenic environment. S. Afr. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 27, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backett-Milburn, K.C.; Wills, W.J.; Gregory, S.; Lawton, J. Making sense of eating, weight and risk in the early teenage years: Views and concerns of parents in poorer socio-economic circumstances. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 624–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backett-Milburn, K.C.; Wills, W.J.; Roberts, M.-L.; Lawton, J. Food, eating and taste: Parents’ perspectives on the making of the middle class teenager. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 1316–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, R.; Chapman, G.E.; Beagan, B. Autonomy and control: The co-construction of adolescent food choice. Appetite 2008, 50, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Shaibu, S.; Maruapula, S.; Malete, L.; Compher, C. Perceptions and attitudes towards food choice in adolescents in Gaborone, Botswana. Appetite 2015, 95, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvert, S.; Dempsey, R.C.; Povey, R. A qualitative study investigating food choices and perceived psychosocial influences on eating behaviours in secondary school students. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 1027–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, K.M.; Qureshi, F.; Schaible, A.; Park, S.; Gittelsohn, J. Environmental Factors That Impact the Eating Behaviors of Low-income African American Adolescents in Baltimore City. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2013, 45, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, N.; Rajaraman, D.; Swaminathan, S.; Vaz, M.; Jayachitra, K.; Lear, S.A.; Punthakee, Z. Perceptions of healthy eating amongst Indian adolescents in India and Canada. Appetite 2017, 116, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, K.W.; Baranowski, T.; Rittenberry, L.; Olvera, N. Social-environmental influences on children’s diets: Results from focus groups with African-, Euro- and Mexican-American children and their parents. Health Educ. Res. 2000, 15, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding-Singh, P. Dining with dad: Fathers’ influences on family food practices. Appetite 2017, 117, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding-Singh, P.; Wang, J. Table talk: How mothers and adolescents across socioeconomic status discuss food. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 187, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgerald, A.; Heary, C.; Nixon, E.; Kelly, C. Factors influencing the food choices of Irish children and adolescents: A qualitative investigation. Health Promot. Int. 2010, 25, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.L.; Gatdula, N.; Bonilla, E.; Frank, G.C.; Bird, M.; Rascón, M.S.; Rios-Ellis, B. Engaging Intergenerational Hispanics/Latinos to Examine Factors Influencing Childhood Obesity Using the PRECEDE–PROCEED Model. Matern. Child Health J. 2019, 23, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, Y.-Y.; Bogart, L.M.; Sipple-Asher, B.K.; Uyeda, K.; Hawes-Dawson, J.; Olarita-Dhungana, J.; Ryan, G.W.; Schuster, M.A. Using community-based participatory research to identify potential interventions to overcome barriers to adolescents’ healthy eating and physical activity. J. Behav. Med. 2009, 32, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, S. Bringing Policy and Practice to the Table: Young Women’s Nutritional Experiences in an Ontario Secondary School. Brock Educ. J. 2015, 24, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunther, C.; Reicks, M.; Banna, J.; Suzuki, A.; Topham, G.; Richards, R.; Jones, B.; Lora, K.; Anderson, A.K.; Da Silva, V.; et al. Food Parenting Practices That Influence Early Adolescents’ Food Choices During Independent Eating Occasions. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2019, 51, 993–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattersley, L.A.; Shrewsbury, V.A.; King, L.A.; Howlett, S.A.; Hardy, L.L.; Baur, L.A. Adolescent-parent interactions and attitudes around screen time and sugary drink consumption: A qualitative study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2009, 6, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidelberger, L.; Smith, C. The Food Environment Through the Camera Lenses of 9-to 13-Year-Olds Living in Urban, Low-Income, Midwestern Households: A Photovoice Project. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2015, 47, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holsten, J.E.; Deatrick, J.A.; Kumanyika, S.; Pinto-Martin, J.; Compher, C.W. Children’s food choice process in the home environment. A qualitative descriptive study. Appetite 2012, 58, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.R.; Trenholm, J.; Rahman, A.; Pervin, J.; Ekström, E.-C.; Rahman, S.M. Sociocultural Influences on Dietary Practices and Physical Activity Behaviors of Rural Adolescents—A Qualitative Exploration. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, J.; Adhikari, K.; Li, Y.; Lindshield, E.; Muturi, N.; Kidd, T. Identifying barriers, perceptions and motivations related to healthy eating and physical activity among 6th to 8th grade, rural, limited-resource adolescents. Health Educ. 2016, 116, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monge-Rojas, R.; Garita, C.; Sánchez, M.; Muñoz, L. Barriers to and Motivators for Healthful Eating as Perceived by Rural and Urban Costa Rican Adolescents. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2005, 37, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Story, M.; Ackard, D.; Moe, J.; Perry, C. The “Family Meal”: Views of adolescents. J. Nutr. Educ. 2000, 32, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dougherty, M.; Story, M.; Lytle, L. Food choices of young African-American and Latino adolescents: Where do parents fit in? J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 1846–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Kang, J.-H.; Lawrence, R.; Gittelsohn, J. Environmental Influences on Youth Eating Habits: Insights from Parents and Teachers in South Korea. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2014, 53, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinard, C.A.; Byker, C.; Harden, S.M.; Carpenter, L.R.; Serrano, E.L.; Schober, D.J.; Yaroch, A.L. Influences on Food Away from Home Feeding Practices Among English and Spanish Speaking Parent–Child Dyads. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2014, 24, 2099–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povey, R.; Cowap, L.; Gratton, L. “They said I’m a square for eating them” Children’s beliefs about fruit and vegetables in England. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 2949–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, T.G.; Bindler, R.C.; Goetz, S.; Daratha, K.B. Obesity Prevention in Early Adolescence: Student, Parent, and Teacher Views. J. Sch. Health 2009, 80, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakhshanderou, S.; Ramezankhani, A.; Mehrabi, Y.; Ghaffari, M. Determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among Tehranian adolescents: A qualitative research. J. Res. Med Sci. 2014, 19, 482–489. [Google Scholar]

- Rathi, N.; Riddell, L.; Worsley, A. What influences urban Indian secondary school students’ food consumption?—A qualitative study. Appetite 2016, 105, 790–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlins, E.; Baker, G.; Maynard, M.; Harding, S. Perceptions of healthy eating and physical activity in an ethnically diverse sample of young children and their parents: The DEAL prevention of obesity study. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 26, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pérez, R.; Correa-Matos, N.; Valdés-Valderrama, A.; Rodríguez-Cruz, L.A.; Rodriguez, R. A Qualitative Study of Puerto Rican Parent and ChildPerceptions Regarding Eating Patterns. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2019, 51, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth-Yousey, L.; Chu, Y.L.; Reicks, M. A Qualitative Study to Explore How Parental Expectations and Rules Influence Beverage Choices in Early Adolescence. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2012, 44, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishak, S.I.Z.S.; Chin, Y.S.; Taib, M.N.M.; Shariff, Z.M. Malaysian adolescents’ perceptions of healthy eating: A qualitative study. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 1440–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, D.C.D.; Frazao, I.D.; Osorio, M.M.; de Vasconcelos, M.G.L. Perception of adolescents on healthy eating. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2015, 20, 3299–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snethen, J.A.; Hewitt, J.B.; Petering, D.H. Addressing Childhood Overweight: Strategies Learned from One Latino Community. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2007, 18, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steeves, E.T.A.; Johnson, K.A.; Pollard, S.L.; Jones-Smith, J.; Pollack, K.; Johnson, S.L.; Hopkins, L.; Gittelsohn, J. Social influences on eating and physical activity behaviours of urban, minority youths. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 3406–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiedje, K.; Wieland, M.L.; Meiers, S.J.; Mohamed, A.A.; Formea, C.M.; Ridgeway, J.L.; Asiedu, G.B.; Boyum, G.; Weis, J.A.; Nigon, J.A.; et al. A focus group study of healthy eating knowledge, practices, and barriers among adult and adolescent immigrants and refugees in the United States. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstraeten, R.; Van Royen, K.; Ochoa-Avilés, A.; Penafiel, D.; Holdsworth, M.; Donoso, S.; Maes, L.; Kolsteren, P. A Conceptual Framework for Healthy Eating Behavior in Ecuadorian Adolescents: A Qualitative Study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Hurtado, G.A.; Flores, R.; Alba-Meraz, A.; Reicks, M. Latino Fathers’ Perspectives and Parenting Practices Regarding Eating, Physical Activity, and Screen Time Behaviors of Early Adolescent Children: Focus Group Findings. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 2070–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs 2013–2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Muzaffar, H.; Metcalfe, J.J.; Fiese, B. Narrative Review of Culinary Interventions with Children in Schools to Promote Healthy Eating: Directions for Future Research and Practice. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2018, 2, nzy016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchinson, J.; Watt, J.F.; Strachan, E.K.; Cade, J.E. Evaluation of the effectiveness of the Ministry of Food cooking programme on self-reported food consumption and confidence with cooking. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 3417–3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overcash, F.; Ritter, A.; Mann, T.; Mykerezi, E.; Redden, J.; Rendahl, A.; Vickers, Z.; Reicks, M. Impacts of a Vegetable Cooking Skills Program Among Low-Income Parents and Children. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevers, D.W.; van Assema, P.; Sleddens, E.F.; de Vries, N.K.; Kremers, S.P. Associations between general parenting, restrictive snacking rules, and adolescent’s snack intake. The roles of fathers and mothers and interparental congruence. Appetite 2015, 87, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahill, S.; Kennedy, A.; Kearney, J. A review of the influence of fathers on children’s eating behaviours and dietary intake. Appetite 2020, 147, 104540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampersaud, G.C.; Pereira, M.A.; Girard, B.L.; Adams, J.; Metzl, J.D. Breakfast Habits, Nutritional Status, Body Weight, and Academic Performance in Children and Adolescents. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2005, 105, 743–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florence, M.D.; Asbridge, M.; Veugelers, P.J. Diet Quality and Academic Performance. J. Sch. Health 2008, 78, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, V.; Loyen, A.; Lodder, M.; Schrijvers, A.J.; van Yperen, T.A.; de Leeuw, J.R. The effects of adolescent health-related behavior on academic performance: A systematic review of the longitudinal evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 2014, 84, 245–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, E.S.; Park, B.M. Health Behaviors and Academic Performance Among Korean Adolescents. Asian Nurs. Res. 2016, 10, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levpušček, M.P. Adolescent individuation in relation to parents and friends: Age and gender differences. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2006, 3, 238–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, N.I.; Story, M.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Food Preparation and Purchasing Roles among Adolescents: Associations with Sociodemographic Characteristics and Diet Quality. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berge, J.M.; MacLehose, R.F.; Larson, N.; Laska, M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Family Food Preparation and Its Effects on Adolescent Dietary Quality and Eating Patterns. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 59, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quelly, S.B. Helping with Meal Preparation and Children’s Dietary Intake: A Literature Review. J. Sch. Nurs. 2019, 35, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Möser, A.; Chen, S.E.; Jilcott, S.B.; Nayga, R.M. Associations between maternal employment and time spent in nutrition-related behaviours among German children and mothers. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 1256–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, K.W.; Hearst, M.O.; Escoto, K.; Berge, J.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Parental employment and work-family stress: Associations with family food environments. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devine, C.M.; Farrell, T.J.; Blake, C.E.; Jastran, M.; Wethington, E.; Bisogni, C.A. Work Conditions and the Food Choice Coping Strategies of Employed Parents. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2009, 41, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datar, A.; Nicosia, N.; Shier, V. Maternal work and children’s diet, activity, and obesity. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 107, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darmon, N.; Drewnowski, A. Does social class predict diet quality? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 1107–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murayama, N.; Ishida, H.; Yamamoto, T.; Hazano, S.; Nakanishi, A.; Arai, Y.; Nozue, M.; Yoshioka, Y.; Saito, S.; Abe, A. Household income is associated with food and nutrient intake in Japanese schoolchildren, especially on days without school lunch. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 2946–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, C. Economic constraints on taste formation and the true cost of healthy eating. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 148, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Kuhn, M.; Prettner, K.; Bloom, D.E. The macroeconomic burden of noncommunicable diseases in the United States: Estimates and projections. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaux, M.; Graf, S.; Goryakin, Y.; Cecchini, M.; Huber, H.; Colombo, F. Obesity Update 2017; Organization for Economic Co-operation Development: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, K.W.; Laska, M.N.; Fulkerson, J.A.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Longitudinal and Secular Trends in Parental Encouragement for Healthy Eating, Physical Activity, and Dieting Throughout the Adolescent Years. J. Adolesc. Health 2011, 49, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Research Office. Information Note: Overall Study Hours and Student Well-Being in Hong Kong; Legislative Council Secretariat: Hong Kong, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shek, D.T.L.; Siu, A.M.H. “UNHAPPY” Environment for Adolescent Development in Hong Kong. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 64, S1–S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, D.L.; Ataie, J.; Carder, P.; Hoffman, K. Introducing Dyadic Interviews as a Method for Collecting Qualitative Data. Qual. Health Res. 2013, 23, 1276–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).