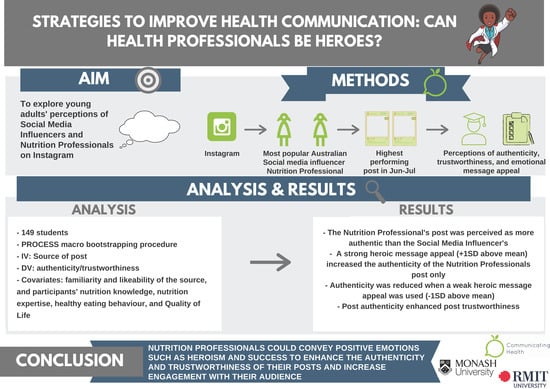

1. Introduction

Communicating health messages clearly and openly to the public is challenging, as much of the evidence focuses on longevity and disease prevention, rather than behaviours that generate instant results and gratification [

1]. Previous research has indicated that young adults and university students are often uninterested in the long-term benefits or consequences of their current eating behaviours [

2,

3]. Whilst nutrition science has enabled countless discoveries and progressions in science [

4], nutrition science is more complicated than other disciplines of science in multiple ways. Firstly, food is an essential part of every human’s life, thus many people have a vested interest in nutrition and care about their health [

5]. Diet quality is typically poor, particularly amongst young adults and university students, and the current obesogenic climate makes healthy choices more challenging than ever before [

6,

7].

Secondly, with the widespread use of social media (SM; see

Appendix A for a glossary of terms), many people without formal qualifications, such as celebrities and social media influencers (herein referred to collectively as SMIs;

Appendix A) are sharing science-related information that is influential and highly accessible to a wide audience. The discipline of nutrition science is riddled with questions surrounding authenticity, trustworthiness, and credibility [

1,

8]. The oversimplification of translating study findings by some media outlets causes confusion among the public. These translation activities often ignore key differences in study design—i.e., methods and the population of interest (human vs. animal studies)—thus causing confusion and lack of trust when results are conflicting. Our work has shown that government translation of nutrition research (i.e., the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating) fails to capture the attention of young adults as it is not relevant and applicable to their lives, unlike content from SMIs [

2].

SM has enhanced the proliferation of ‘fad diets’, particularly those which restrict whole food groups (e.g., the paleo diet; grains and dairy), thus limiting the variety in our diets. Young adults are the biggest consumers of SM content, with approximately 70% of 18–24-year-olds using Instagram (

Appendix A) [

9], and University students feeling permanently connected to SM [

10]. However, our systematic review identified that the use of SM for health interventions in young adults had limited success with highly variable engagement rates (

Appendix A) ranging from 3–69% [

11]. Health professionals often have jobs outside of SM, and are bound by professionalism principles, [

12] and thus may not be as candid or have as much time as SMIs to grow their audience and spread evidence-based information, potentially limiting their ability to engage young people.

In the existing post-truth era (

Appendix A), experts are often less highly regarded by young adults and emotional message appeals (

Appendix A) are typically the most effective methods of communication [

13,

14,

15]. Previous research has detailed the effectiveness of positive emotional message appeals, such as humour (

Appendix A), as a way to increase engagement on SM [

16,

17,

18]. On Instagram, young adults are surrounded by the pressure of idyllic lifestyles, frequently being exposed to accounts promoting ‘#fitspiration’ and ‘#cleaneating’ encouraging self-comparison and negative self-image [

19,

20]. Many of the photos on Instagram are heavily edited, creating unrealistic expectations and impacting vulnerable people; particularly women, who are trying to fit-in with others online [

20,

21]. Exposure to image-related content is associated with higher body dissatisfaction, dieting or restricting food, overeating, and choosing healthy foods in young adults; hence, the mental and emotional impact of SMa differs between individuals [

20]. Young adults often feel pressure to be healthy due to the tendency to compare themselves to others, however, they frequently lack the motivation or ability to successfully make healthy behaviour changes due to many environmental and social barriers [

2]. This sub-population is an important target for health interventions to increase the capacity to adopt healthy eating behaviours, which aid in reducing the risk of chronic disease later in life [

2,

22,

23]. Therefore, exploring the perceived trustworthiness, authenticity, and message appeals of nutrition professionals (NPs;

Appendix A) and SMIs on Instagram could be useful to inform health communication techniques targeted at young adults in the future. Some NPs could be considered SMIs, but the distinguishing factor in our study is the presence or absence of a tertiary qualification in nutrition (

Appendix A).

This paper is informed by the self-determination theory (

Appendix A) and the source credibility model (

Appendix A). The self-determination theory encompasses the concept of authenticity, defined as “being true to the self in terms of an individual’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviours reflecting their true identity” (

Appendix A) [

24]. In the marketing literature, individuals tend to perceive another person (e.g., a celebrity) as authentic when the other person’s actions reflect their autonomous, self-determining, true self [

25]. Those who are perceived as authentic have a higher level of influence over others, both online and offline [

26]. Source credibility is a communicator’s positive characteristics that affect the receiver’s acceptance of a message, encompassing attractiveness, trustworthiness, and expertise [

27]. In these analyses, we focus primarily on trustworthiness.

Our scoping review has highlighted the paucity of research from health and nutrition science that considers the trustworthiness or authenticity of a spokesperson’s communications [

28]. The aim of this paper was to understand the differences in consumer’s perceptions of NPs and SMIs on Instagram through exploring authenticity and trustworthiness. In marketing, authenticity and trustworthiness are distinct constructs; however, research has found that the perceived authenticity of celebrities and brands increases their trustworthiness (e.g., authentic brands are more likely to be trusted by consumers compared to inauthentic brands) [

29,

30]. Based on the health and marketing literature, it is hypothesised that SMIs are similar to celebrity endorsers (who are perceived as authentic [

31];

Appendix A) as they are both recognised as authorities in their specific fields [

29], and, therefore, consumers will perceive the Instagram post of the SMI (versus NP) as more: (1) authentic; and (2) trustworthy. Given that positive or gain-framed messages have been found to more effectively promote the adoption of healthy eating behaviours [

2,

32,

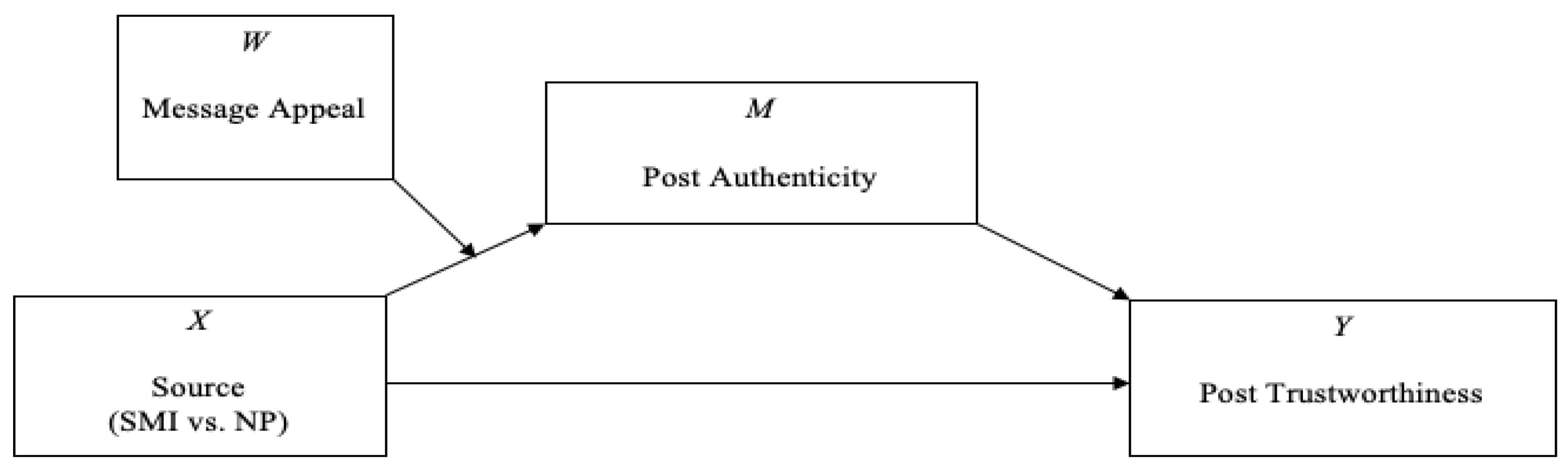

33], we hypothesise that a positive message appeal will influence the authenticity of SMIs’ (versus NPs) Instagram posts.

4. Discussion

It was hypothesised that the SMI would be more trustworthy and authentic than the NP based on the extensive celebrity endorsement literature, whereby an Instagram influencer is akin to a true celebrity [

29,

46]. However, the results of this study provide initial evidence that the NPs post was perceived by young adults to be more authentic, and subsequently, more trustworthy, than a SMIs post. We provide evidence of this relationship irrespective of the young adults’ gender, BMI, familiarity with the source, likability of the source, self-reported quality of life, healthy eating behaviour, subjective nutrition knowledge, or subjective nutrition expertise. Therefore, hypothesis 1 and hypothesis 2 were not supported.

Communicating health through SM is challenging, and research focused on the methodology for improving SM engagement for NPs is currently lacking. In this study, a novel concept in this field of research was examined: the perceived authenticity and trustworthiness of NPs posts compared to SMIs. SMIs often promote damaging fad-diets and share misinformation without consequence; whilst NPs promote evidence-based sustainable diet changes for disease prevention. Currently, Instagram and Facebook are unregulated in regard to health misinformation, with the exception of COVID-19 related information. In 2019, a policy was introduced that prevented diet supplements being advertised to under 18 year olds [

47] which is a step in the right direction. We await the application of these techniques to other areas in regard to stemming the proliferation of misinformation. Our previous research has identified many factors that may impact the trustworthiness and authenticity of such posts such as number of followers, message appeal, and authority cues [

28]. However, there is a paucity of research on the influence of either NPs or SMIs on perceived trustworthiness and authenticity of SM posts [

28].

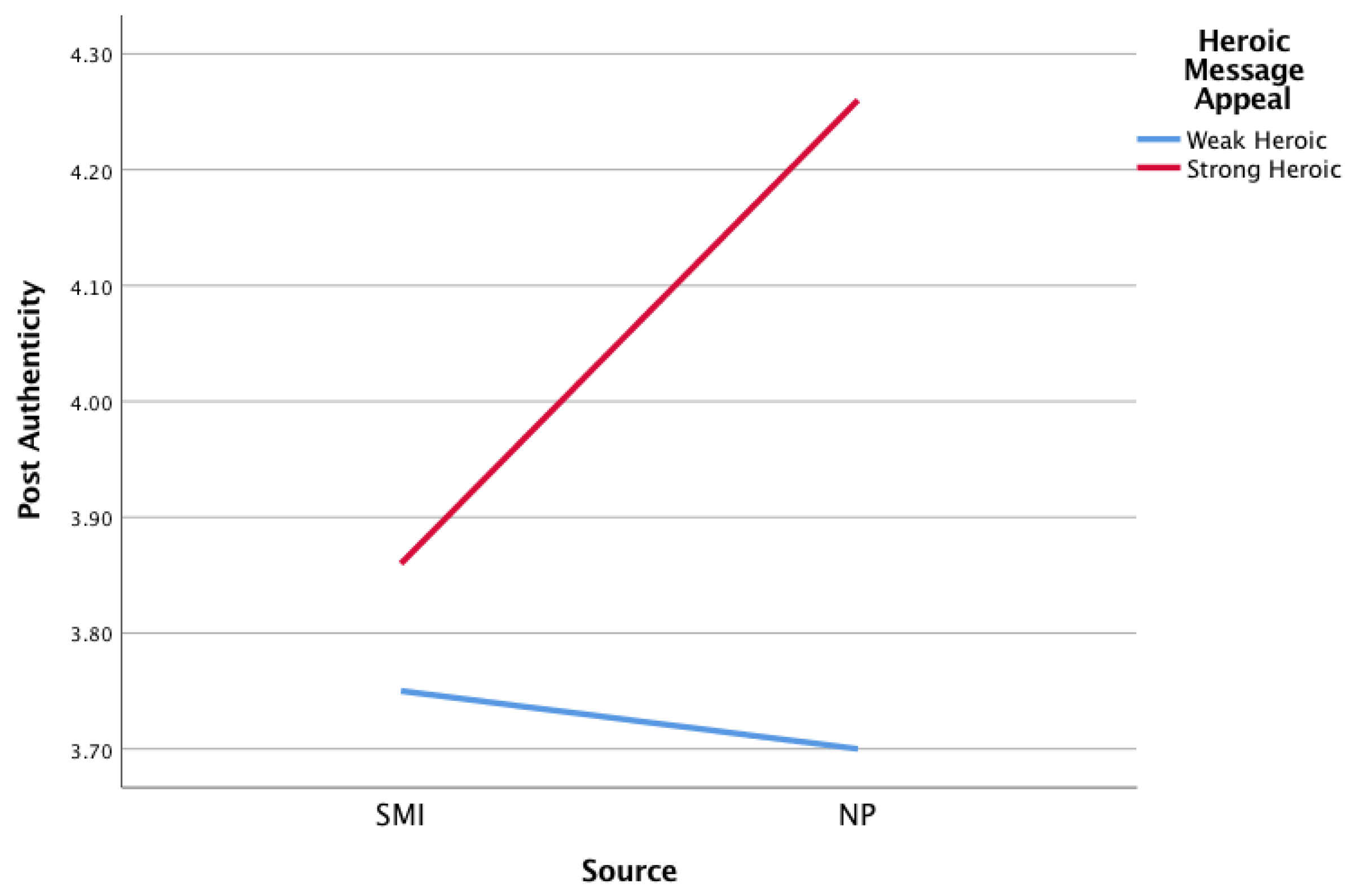

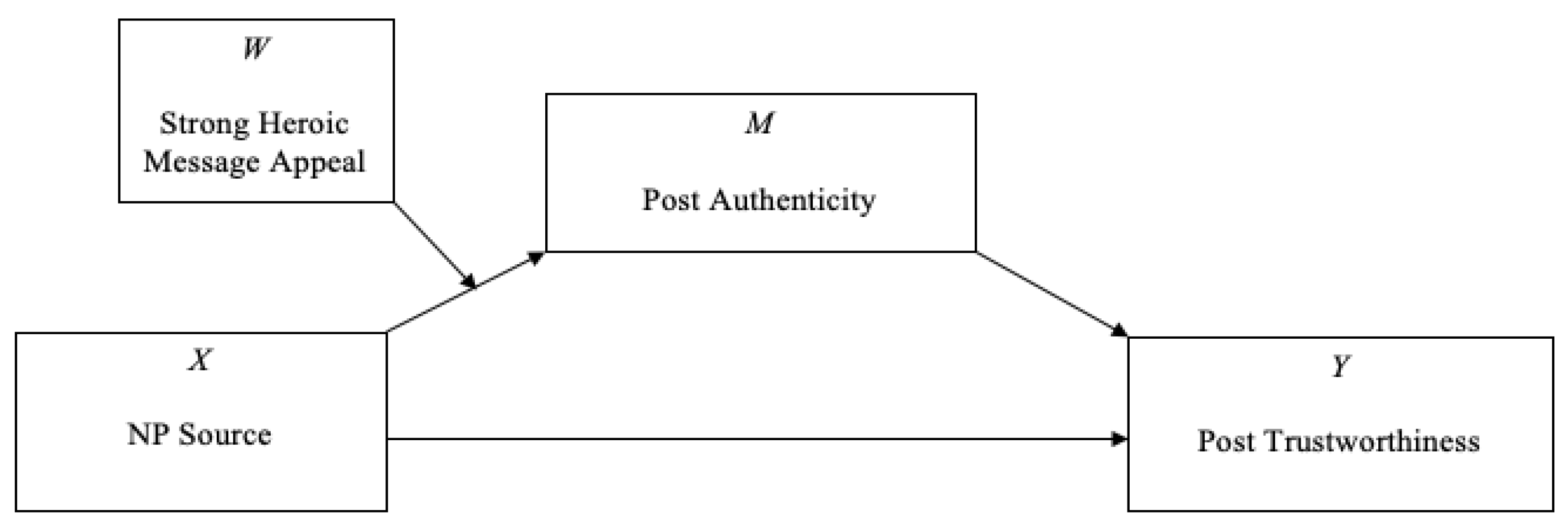

Based on our exploratory results, we further showed that the authenticity of the NP’s posts was dependent on the perceived strength of the heroic message appeal communicated. A NP’s post was perceived as more authentic, and subsequently more trustworthy, when the message appeal used in the post was perceived to be strongly heroic. On the other hand, the authenticity of the NP’s post was perceived as significantly less authentic, and subsequently less trustworthy, when their message appeal was perceived to be weak in heroism. In other words, it is suggested that, when appropriate, NPs attempt to convey positive emotions relating to heroism such as bravery, nobility, and success, in their messages in order to enhance the genuineness and realness of their posts.

Whilst the authenticity of NPs’ messages, or content, has not been directly measured to date (to the authors’ knowledge), the medical literature highlights the importance of authenticity driving the motives of health professionals, such as doctors and nurses [

48]. Conceptualisations of authenticity in health surround the themes of genuineness, consistency, and caring [

48,

49]. Trust is also an important consideration in healthcare settings, with trusted professionals being more likely to lead their patients to better health outcomes and consequently, quality of life [

50]. The current literature (from clinical settings) suggests that health professionals can develop trusting relationships through being non-judgemental and encouraging two-way interaction between themselves and patients [

51]. However, young adults have previously identified lack of trust and communication difficulties as important factors contributing to negative healthcare experiences [

52]. Trusting relationships are essential in achieving behavioural change over SM; as those on SM platforms who have higher trust from their audience have a higher level of influence over others’ behaviours [

53]. In a review looking at the efficacy of using SM for achieving nutrition outcomes in young adults, it was found that while young adults considered SM an acceptable source for health information, they preferred a one-way conversation, regarding health with professionals through SM and did not wish to discuss their weight [

11]. In addition, health and fitness information shared through University affiliated SM pages has been found to be acceptable by University students [

54].

Young adults constitute the audience of many SMIs, who share their personal life online and attract a loyal following, wanting to form a personal connection. This is known as a ‘parasocial relationship’ (

Appendix A), thus creating an illusion of intimacy and friendship, despite the majority of followers remaining unknown by the SMI [

55]. In contrast, NPs must maintain a sense of professionalism online and, therefore, typically cannot create the same type of content without risking the loss of their professional image [

56]. However, in this study, the caption in the NP’s post is a vulnerable description of when she was struggling with weight-loss. This use of vulnerability may perhaps not be the ‘norm’ for NPs on SM, but it does provide strategies for how professionalism and vulnerability may be combined, as suggested by the celebrity literature from marketing and psychology [

25,

57,

58]. One study looking at the authenticity of bloggers found that bloggers who shared their innermost thoughts and many facets of their personal life on their blog were seen as more relatable and authentic than those who were less open about their personal life [

49].

In both commercial and social marketing, message appeal is often manipulated to influence consumer’s emotions and generate a greater persuasive capacity [

16]. There is limited research published in health and medicine that considers the effectiveness of varying message appeals over SM [

16]. However, those published emphasise the effectiveness of positive emotional appeals to increase engagement with public health messages [

59,

60]. Specifically, a ‘heroic’ message appeal, associated with bravery and nobility, is not commonly researched in the literature, with many studies focusing on negative emotional appeals such as ‘guilt’, ‘fear’, and ‘shame’, or single positive appeals such as ‘humour’ [

16,

59]. Negative emotional appeals can often result in feelings detrimental to an individual’s wellbeing [

61], and have been found to lead to the ‘flight, fight, or freeze’ response, eliciting a longer-lasting impact on the nervous system when compared to positive appeals [

62]. As detailed in Self-Determination Theory, an individual should be autonomous in their decision making to attain long-lasting behaviour change [

62]. Individuals exposed to negative appeals without control over their exposure (i.e., seeing an advertisement on TV), can result in an ‘avoidance motivation’, whereby an individual makes effort to avoid anything they anticipate will cause sadness and anxiety [

63], hence scare tactics are not always effective in influencing behaviours. Our online conversations provide further evidence of needing to move away from negative rhetoric, as guilt appeals around healthy eating did not work on young adults who did not hold the same beliefs about health (e.g., ‘sinners’) [

35]. Traditionally, health promotion organisations have maintained a serious message and utilised rational message appeals (e.g., facts, statistics) over emotional appeals, generating lower engagement rates from their audience [

11,

17,

18,

64]. Young adults have indicated that healthy eating messages would be more persuasive if they incorporated empathy, while an authoritative message was rated poorly for perceived ability to encourage healthy eating [

65]. The findings from our study suggest that by focusing on positive emotional appeals such as heroism, the audience can empathetically connect with NPs, which could lead to greater engagement rates. Specifically, results from the regression analysis indicated that a perceived ‘strong’ heroic message appeal resulted in a more authentic perception of the NP’s post, and when using a ‘weak’ perceived heroic message appeal, the authenticity of both the SMI’s and NP’s post was reduced.

This research has highlighted the importance placed on message appeal in assessing the authenticity of SM posts, especially those of NPs. NPs could benefit from communicating their success and bravery to increase the authenticity of their posts. Although this study found that young adults were less likely to perceive the posts of SMIs as authentic and trustworthy, consumers are often inspired by celebrities and influencers, and follow them to learn from their experiences with different diets and exercise regimes. Many SMIs advertise one-on-one consultation sessions, and sell personalised meal plans, exercise eBooks, and nutritional supplements based on anecdotal evidence and pseudoscience [

66,

67,

68]. As the number of followers increases for SMIs, there are more consumers trying the behaviours promoted, reflecting ‘herd behaviour’ (

Appendix A), the phenomenon of individuals deciding to follow others and imitating group behaviours rather than deciding independently on the basis of their own, private information [

15,

69]. Herd behaviour can trigger a larger trend, which could be harmful to many people, particularly if it is based on unqualified advice. To our knowledge, there are no consistent ways for the public to identify credentialed health professionals and scientists, particularly on SM. NPs need to be cognisant of the different communication strategies used in the online environment and focus on educating the public through sharing relatable evidence-based health advice.

The profiles and posts included in the survey were sourced based on objective engagement metrics rather than being subjectively chosen by the researchers. Real-life profiles and posts were used rather than fictional characters, making the study more realistic and providing a true sense of consumers’ perceptions of the SMI and NP. Furthermore, the use of validated scales to assess consumer perceptions produced excellent Cronbach’s α scores for all measures (

Table 2) and ensured the survey measured what it was intended to.

The experimental nature of this study—rather than a real-life setting, as well as the convenience sample of University students participating as part of their coursework requirements—limits the generalisability of these results to the wider population of young adults. Furthermore, the use of student participants limits the variability of results as students samples (referred to as western, educated, industrialised, rich, and democratic (WEIRD)) [

70] are seen as more homogenous in terms of education level and socioeconomic status than the general public. Additionally, the two Instagram profiles sourced by Socialbakers

© were both young and conventionally attractive females, which could have affected the variability of results. In an effort to keep the posts as similar to real as possible, the number of likes was visible, however there was a large difference between sources (SMI 282,711, NP 2686) which could have impacted participants’ perceptions. The messages in the SMI and NP posts were also discussing different topics (NP: body image, SMI: relationships) which could have unknowingly affected results. In this pilot study, we focussed on measuring the trustworthiness of the Instagram posts. Future iterations should consider adapting the questions to measure perceived expertise and attractiveness (if the person is shown in the photo) of the SMI and NP based on the Instagram posts. Future research could use an experimental design to manipulate the message in the caption and/or number of likes on the Instagram posts to examine the effect of message topic and bandwagon cues on trustworthiness and authenticity. Further research is required to enhance the understanding of trustworthiness and authenticity on SM, as well as to validate these findings using male SMIs and NPs, and non-student young adult populations.