Improving the Reporting of Young Children’s Food Intake: Insights from a Cognitive Interviewing Study with Mothers of 3–7-Year Old Children

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Recruitment

2.2. Short Food Questions (SFQ)

2.3. Study Protocol

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

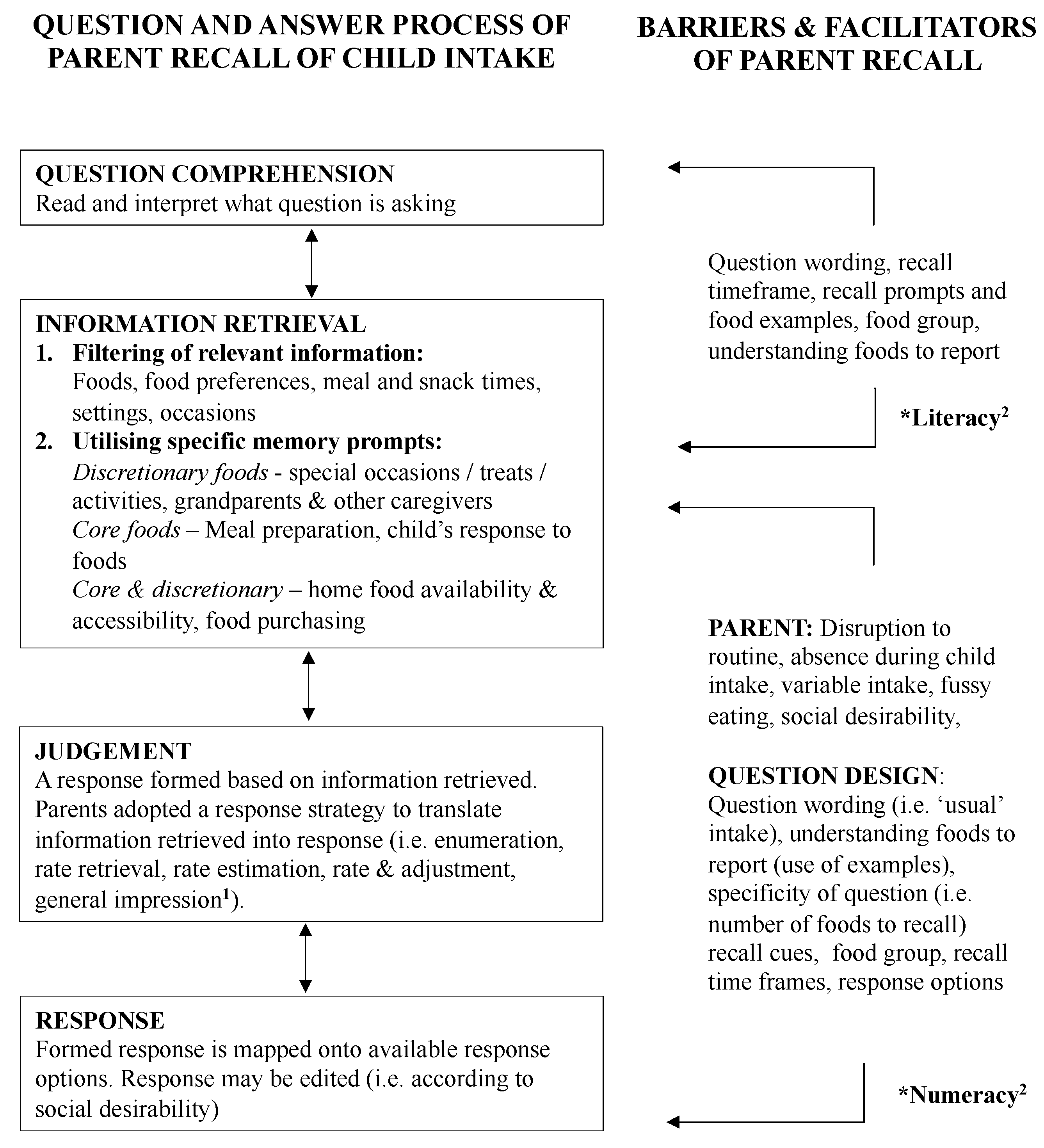

3.2. Recall Process Used to Report Children’s Intake

3.3. Information Retrieval

3.3.1. Step One—Filtering Relevant Information

3.3.2. Step Two—Use of Specific Memory Prompts

3.4. Response Strategies Used to Estimate Food Intake

3.5. Barriers to and Facilitators of Reporting Children’s Dietary Intake

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| THINK-ALOUD PRACTICE EXAMPLE |

| “Try to visualize the place where you live and think about how many windows there are in that place. As you count the windows, tell me what you are seeing and thinking about to work out the number of windows.” |

| THINK-ALOUD |

| “Now I would like you to read each question out loud, and as you are deciding on your answer say everything that you are thinking.” Prompts if needed: What are you thinking? What are you thinking about right now? Tell me what you’re thinking. Read the question out loud. |

| SEMI-STRUCTURED INTERVIEW GUIDE |

| GENERAL: How did the participant arrive at the answer? What did you think about to work out your answer? I noticed that you hesitated…What were you thinking about? Can you tell me in your own words what you think this question means? |

| COMPREHENSION: How was the question/food group interpreted? What foods did you include/consider when you were thinking about [X food group]? What do you understand by [X food group]? Was there anything that you didn’t understand? Were there any foods that you weren’t sure about whether to include or exclude from your answer? |

| RECALL: Recall processes used to arrive at the answer What did you think about when trying to recall that [your child] had [x foods]? What foods/meal occasions did you think about to determine/calculate your answer? Was there anything else you thought about when trying to work out how much/how often [child] eats [X]? |

| CONFIDENCE: How sure are you of your answer? |

| DIFFICULTY OF QUESTION: How easy or difficult did you find this question to answer? |

| RESPONSE OPTIONS: Were you able to find the right answer from the response options given? |

| QUESTIONNAIRE SPECIFIC FOLLOW-UP QUESTIONS FOR PDQ—PORTION SIZE |

| How did you think about/work out portion size? Were the portion size responses appropriate for your child? How easy or difficult did you find it to consider the serving sizes specified for [X food group]? How does the portion (amount) that your child usually eats compare to the serving sizes that are specified in the question? |

References

- Abarca-Gómez, L.; Abdeen, Z.A.; Hamid, Z.A.; Abu-Rmeileh, N.M.; Acosta-Cazares, B.; Acuin, C.; Adams, R.J.; Aekplakorn, W.; Afsana, K.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.A.; et al. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2017, 390, 2627–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, E.; de Silva-Sanigorski, A.; Burford, B.J.; Brown, T.; Campbell, K.J.; Gao, Y.; Armstrong, R.; Prosser, L.; Summerbell, C.D. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, R.; Bell, L.; Taylor, R.W.; Mauch, C.; Mihrshahi, S.; Zarnowiecki, D.; Hesketh, K.D.; Wen, L.M.; Trost, S.G.; Golley, R. Brief tools to measure obesity-related behaviours in children under 5 years of age: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 432–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magarey, A.; Watson, J.; Golley, R.K.; Burrows, T.; Sutherland, R.; McNaughton, S.A.; Denney-Wilson, E.; Campbell, K.; Collins, C. Assessing dietary intake in children and adolescents: Considerations and recommendations for obesity research. Int. J. Pediatric Obes. 2011, 6, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPherson, R.S.; Hoelscher, D.M.; Alexander, M.; Scanlon, K.S.; Serdula, M.K. Dietary Assessment Methods among School-Aged Children: Validity and Reliability. Prev. Med. 2000, 31, S11–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golley, R.K.; Bell, L.K.; Hendrie, G.A.; Rangan, A.M.; Spence, A.; McNaughton, S.A.; Carpenter, L.; Allman-Farinelli, M.; Silva, A.; Gill, T. Validity of short food questionnaire items to measure intake in children and adolescents: A systematic review. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 30, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrie, G.A.; Viner Smith, E.; Golley, R.K. The reliability and relative validity of a diet index score for 4–11-year-old children derived from a parent-reported short food survey. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 1486–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, F.G.; Brown, N.R.; Cashman, E.R. Strategies for Estimating Behavioural Frequency in Survey Interviews. Memory 1998, 6, 339–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subar, A.F.; Freedman, L.S.; Tooze, J.A.; Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Boushey, C.; Neuhouser, M.L.; Thompson, F.E.; Potischman, N.; Guenther, P.M.; Tarasuk, V. Addressing current criticism regarding the value of self-report dietary data. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 2639–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N. Cognitive aspects of survey methodology. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2007, 21, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourangeau, R.; Rips, L.J.; Rasinski, K. The Psychology of Survey Response; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, D. Pretesting survey instruments: An overview of cognitive methods. Qual. Life Res. 2003, 12, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, E.; Burton, S. Cognitive processes used by survey respondents to answer behavioral frequency questions. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 14, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, S.; Blair, E. Task conditions, response formulation processes, and response accuracy for behavioral frequency questions in surveys. Public Opin. Q. 1991, 55, 50–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drennan, J. Cognitive interviewing: Verbal data in the design and pretesting of questionnaires. J. Adv. Nurs. 2003, 42, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, E.T.; Campbell, M.K.; Honess-Morreale, L. Use of cognitive interview techniques in the development of nutrition surveys and interactive nutrition messages for low-income populations. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2002, 102, 690–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Kozlow, M.; Matt, G.E.; Rock, C.L. Recall strategies used by respondents to complete a food frequency questionnaire: An exploratory study. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 430–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, W.S.; Frongillo, E.A.; Cassano, P.A. Evaluating brief measures of fruit and vegetable consumption frequency and variety: Cognition, interpretation, and other measurement issues. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2001, 101, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banna, J.C.; Becerra, L.E.V.; Kaiser, L.L.; Townsend, M.S. Using qualitative methods to improve questionnaires for Spanish speakers: Assessing face validity of a food behavior checklist. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, G.B.; Royston, P.; Bercini, D. The use of verbal report methods in the development and testing of survey questionnaires. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 1991, 5, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, G.B. Cognitive Interviewing. A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design; Sage Publications: California, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4364.0.55.007—Australian Health Survery: Nutrition First Results—Food and Nutrients, 2011–2012; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2014.

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Dietary Guidelines; National Health and Medical Research Council: Canberra, Australia, 2013.

- Department of Health. Discretionary Food and Drink Choices. Available online: https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/food-essentials/discretionary-food-and-drink-choices (accessed on 31 May 2020).

- Magarey, A.; Golley, R.; Spurrier, N.; Goodwin, E.; Ong, F. Reliability and validity of the Children’s Dietary Questionnaire; a new tool to measure children’s dietary patterns. Int. J. Pediatric Obes. 2009, 4, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, L.K.; Golley, R.K.; Mauch, C.E.; Mathew, S.M.; Magarey, A.M. Validation testing of a short food-group-based questionnaire to assess dietary risk in preschoolers aged 3–5 years. Nutr. Diet. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janghorban, R.; Roudsari, R.L.; Taghipour, A. Skype interviewing: The new generation of online synchronous interview in qualitative research. Int. J. Qual Stud. Health Well-Being 2014, 9, 24152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVIVO, 11; QSR International Pty Ltd.: Doncaster, Australia, 2015.

- Liamputtong, P. Qualitative data analysis: Conceptual and practical considerations. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2009, 20, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.E.; Gleason, P.M.; Sheean, P.M.; Boushey, C.; Beto, J.A.; Bruemmer, B. An introduction to qualitative research for food and nutrition professionals. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subar, A.F.; Thompson, F.E.; Smith, A.F.; Jobe, J.B.; Ziegler, R.G.; Potischman, N.; Schatzkin, A.; Hartman, A.; Swanson, C.; Kruse, L. Improving food frequency questionnaires: A qualitative approach using cognitive interviewing. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1995, 95, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matt, G.E.; Rock, C.L.; Johnson-Kozlow, M. Using recall cues to improve measurement of dietary intakes with a food frequency questionnaire in an ethnically diverse population: An exploratory study. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 1209–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickin, K.L.; Lent, M.; Lu, A.H.; Sequeira, J.; Dollahite, J.S. Developing a Measure of Behavior Change in a Program to Help Low-Income Parents Prevent Unhealthful Weight Gain in Children. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2012, 44, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, M.S.; Shilts, M.; Ontai, L.; Leavens, L.; Davidson, C.; Sitnick, S. Obesity risk for young children: Development and initial validation of an assessment tool for participants of federal nutrition programs. Forum Fam. Consum. Issues (FFCI) 2014. Available online: https://www.theforumjournal.org/about-the-forum/ (accessed on 31 May 2020).

- Lindsay, A.C.; Sussner, K.M.; Greaney, M.; Wang, M.L.; Davis, R.; Peterson, K.E. Using Qualitative Methods to Design a Culturally Appropriate Child Feeding Questionnaire for Low-Income, Latina Mothers. Matern. Child. Health J. 2012, 16, 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Thoyre, S.M.; Pados, B.F.; Park, J.; Estrem, H.; Hodges, E.A.; McComish, C.; Van Riper, M.; Murdoch, K. Development and content validation of the pediatric eating assessment tool (Pedi-EAT). Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 2014, 23, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, G.; Yorkston, E.A. The use of memory and contextual cues in the formation of behavioral frequency judgements. In The Science of Self-Report: Implications for Research and Practice; Stone, A.A., Bachrach, C.A., Jobe, J.B., Kurtzman, H.S., Cain, V.S., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cogn. Psychol. 1973, 5, 207–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domel, S.B.; Thompson, W.O.; Baranowski, T.; Smith, A.F. How children remember what they have eaten. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1994, 94, 1267–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, K.; Chan, F.; Prichard, I.; Coveney, J.; Ward, P.; Wilson, C. Intergenerational transmission of dietary behaviours: A qualitative study of Anglo-Australian, Chinese-Australian and Italian-Australian three-generation families. Appetite 2016, 103, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, G. Are the parts better than the whole? The effects of decompositional questions on judgments of frequent behaviors. J. Mark. Res. 1997, 34, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Child Diet Questionnaire (CDQ) [26] | Pre-Schooler Dietary Questionnaire (PDQ) [27] | Short Food Survey (SFS) [7] | TOTAL (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meat and alternatives | N/A | 2-items: How many times in past 7 days and how much (per time) did your child consume: Red meat; Fresh fish. n = 7 | 4-items: How often does your child usually have: Red meats; White meats; legumes or meat alternatives; Eggs. n = 6 | 13 |

| Grains | N/A | 1-item: How many times in past 7 days and how much (per time) did your child consume: Grains (not including bread, noodles or pasta) n = 8 | 3-items: How often does your child usually have: Bread; Pasta, rice, noodles or other cooked cereals; Breakfast cereals n = 7 | 15 |

| Vegetables | 3-items: Vegetables (cooked or raw) your child has eaten over past 7 days; How often has your child had vegetables past 24 h; How many different vegetables past 24 h n = 5 | 3-items: How many times in past 7 days and how much (per time) did your child consume: Green and brassica vegetables; Orange vegetables; Other vegetables n = 5 | 3-items: How often does your child usually have: Starchy vegetables; Salad vegetables; Cooked vegetables n = 4 | 14 |

| Discretionary foods | 13-items: How many times has your child eaten these foods/drinks over past 7 days: Peanut butter/Nutella; Pre-sugared cereal; Sweet biscuits, cakes, etc; potato crisps, savory biscuits; lollies, muesli bars; Chocolate; Soft drink/cordial; Ice-cream; Pie, pasty, sausage roll; Pizza; Hot chips; Processed meats; Takeaway n = 7 | 6-items: How many times in past 7 days and how much (per time) did your child consume: Chips, pop-corn; hot potato products; meat products; sweet biscuits, cakes etc; chocolate; ice-cream n = 7 | 10-items: How often does your child usually have: Soft-drink, cordial, sports drinks; Fruit drinks; Takeaway; Hot potato products; savoury snacks; Sweet biscuits, cakes. etc; savoury pastries; Chocolate/lollies; Ice-cream; Meat products. n = 7 | 21 |

| Response options: | Tick Yes/no; OR Number of times Nil-5+ | Nil, 1, 2–4, ≥5 times AND Nil—specified portion size consumed per time (cooking measurements e.g., cup, tablespoon, number of slices/pieces) | How often: doesn’t eat, each day, each, week, each month, AND how many times per frequency | |

| TOTAL (n) | 12 | 27 | 24 |

| Parent | Child | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) * | 36.2 ± 3.7 | 4.3 ± 1.2 |

| Gender—Female (%) | 100.0 (21) | 57.1 (12) |

| Number of children in family (%) * | ||

| One child | 35.0 (7) | |

| More than one child | 65.0 (13) | |

| Marital status—married/living with partner (%) * | 90.5 (19) | |

| Ethnicity—Caucasian (%) * | 100.0 (20) | |

| Australian State of residence (%) | ||

| South Australia—Adelaide | 71.4 (15) | |

| South Australia—Rural | 9.5 (2) | |

| Australian Capital Territory | 9.5 (2) | |

| Queensland | 4.8 (1) | |

| Tasmania | 4.8 (1) | |

| Socioeconomic status (SEIFA decile) | ||

| Low (decile 1–3) | 28.6 (6) | |

| Middle (decile 4–7) | 23.4 (5) | |

| High (decile 8–10) | 47.6 (10) | |

| Education level (%) * | ||

| Completed high school | 4.8 (1) | |

| Trade certificate or diploma | 9.5 (2) | |

| University or tertiary qualification | 33.3 (7) | |

| Postgraduate university degree | 47.6 (10) | |

| Employment status (%) * | ||

| Full-time employment | 19.0 (4) | |

| Part-time employment | 47.6 (10) | |

| Self-employed | 14.3 (3) | |

| Home duties | 9.5 (2) | |

| Student | 4.8 (1) | |

| Child dietary restrictions (%) | ||

| None | 81.0 (17) | |

| Vegetarian child | 4.8 (1) | |

| Vegetarian mother (no meat at home) | 4.8 (1) | |

| Peanut allergy | 4.8 (1) | |

| Avoid dairy | 4.8 (1) |

| Theme | Example Quote |

|---|---|

| RECALL PROCESS USED BY PARENTS | |

| Information retrieval step one—filtering relevant information | Food preferences: “He doesn’t eat a lot of meat. He doesn’t like it so looking at that list and the only thing is ham and fritz that he eats and I’ll offer ham probably a couple of times a week…”—Mother 2 (SFS Discretionary) Usual routine (recall of core foods a): “I think just generally thinking about the schedule of the week, so what day we had people over, what we do every night of the week. My husband has basketball on Tuesday night, so that’s what triggered for me the memory of what we had for dinner that night. ”—Mother 9 (PDQ Grains) Disrupted routine (recall of discretionary foods b): “…I was thinking what are the unusual circumstances that would have led to her eating those kind of things”—Mother 13 (PDQ discretionary) Meal and snack times: “…I’m thinking of dinners. That’s when we normally eat all of our vegies. And I’m also thinking of lunches. Main meals is our vegie intake.”—Mother 2 (CDQ vegetables) |

| Information retrieval step two—use of specific memory prompts | Occasions, events, treats and activities: “We wouldn’t just have them at home… So I’m trying to think how often we have an occasion that is linked to that type of treat.”—Mother 4 (SFS discretionary) Grandparents and other care givers: “I have a feeling that my husband took him out Saturday and gave him one [pie, pasty or sausage roll].”—Mother 11 (CDQ discretionary) “See this [cakes, biscuits, buns, muffins] is a grandparent’s specialty. So I suspect that he would probably have had them three times in the past week.” – Mother 3 (PDQ discretionary) Meal preparation: “We would probably have spaghetti bolognaise once a week, but he doesn’t eat the meat. We would have a roast probably once a week where he does eat the meat. And we would have chops or stir fry and he would eat the chops but not the stir fries.”—Mother 17 (SFS meat) Children’s response to food: “I’m thinking about how often I serve them against how much she actually consumes of them. I’d be wanting to say each day; she doesn’t eat them every day. But I give them to her every day.”—Mother 5 (SFS vegetables) “I was also thinking about what he actually ate. Because with the lettuce I know that he pulled some of the lettuce out and put it on my plate.”—Mother 16 (CDQ vegetables) Home food availability (core foods): “Knowing what sort of foods we have in the, in the fridge, in the pantry, again I’m very consistent with that.”—Mother 13 (PDQ vegetables) Home food availability and accessibility (discretionary foods): “Sweet biscuit dishes are high and still pre stocked so they haven’t snuck into there. Although she did take some biscuits, sweet biscuits today.”—Mother 15 (PDQ discretionary) Food purchasing: “I’m trying to remember what was in the shopping trolley because that’s probably what we actually ended up eating and what’s in the fridge.”—Mother 18 (CDQ vegetables) |

| BARRIERS AND FACILITATORS OF REPORTING CHILDREN’S DIETARY INTAKE | |

| Understanding of foods to report | “We do our own chips. So we get a potato, cut it and cook it on the barbie and we call them chips…Is that included as a homemade chip, it’s similar to a roast? It’s not deep fried, its maybe got a little bit of olive oil on it.”—Mother 3 (PDQ discretionary) |

| Specificity of questions | “It’s good having the little prompts saying including this, because that makes me think about what he would eat, and what he wouldn’t eat.”—Mother 14 (PDQ discretionary) |

| Reporting portion size | Estimating in units: “Like the chocolate, two pieces, two to three pieces, seven to fourteen pieces, that’s really clear, it’s easy to work out. But if it said a hundred grams of chocolate I’d be like, well I don’t know how much a hundred grams is.”—Mother 13 (PDQ discretionary) Cognitive load of converting intake to response option: “We took a whole packet in the boat but there was seven of us that shared it so I’m trying to think of how that would have divvied out. [Pause] It’s probably, I don’t know, a hundred- and eighty-gram bag, those big ones I think…so divide that by seven. It’s more than twenty grams each”—Mother 15 (PDQ discretionary) Guesstimating portion size: “So, again, I’d be guessing. I have no idea about how many grams of chips [laughs] she consumes… I’d be guessing but I think I’d go for the middle one, half to one, small packet. I’m guessing on that one because it’s in the middle so it’s the average.”—Mother 5 (PDQ discretionary) |

| Recall time frame | “I can actually think of the last seven days and answer it with some confidence.”—Mother 19 (CDQ discretionary) |

| Recall difficulties | “I can remember one specific time of cooking read meat, and I just don’t know whether I cooked it again. So, I couldn’t really tell you between once or two to four times at this point in time. I would err on the side of safety and say it’s two to four times.”—Mother 1 (PDQ meat) |

| Unsure of foods child consumes when away from parents | “The complication around this is that I’m looking at dinner meals but I know that my son is at an early learning centre and they also have cooked meals, not just sandwiches but I have no idea what regularly they have… So that’s the thing I’m just completely disregarding…”—Mother 3 (SFS meat) |

| Frequency versus portion size | “We’ve had quite a lot of salad this week, but he’s not too keen on lettuce…I’d probably tick yes, he’s had it, but it would be a miniscule amount.”—Mother 16 (CDQ vegetables) |

| Child fussy eating | “So that’s difficult because I can easily remember when I offer. It’s harder to remember what they actually eat because I don’t write it down or catalogue it.”—Mother 18 (CDQ vegetables) |

| Reporting ‘usual’ intake | “We’ve had [takeaway] a lot more in the last week than we usually would. So I’m wondering should I do what would be an average week or what has been the last week?”—Mother 6 (SFS discretionary) |

| Social desirability | “…we have Coco Pops in the school holidays, so if we’re talking the past seven days, that doesn’t look so good, does it?”—Mother 9 (CDQ discretionary) “It was confronting (laughs) because I had to admit to myself how many times I feed kids the foods I tell myself I’m not going to feed the kids.”—Mother 4 (SFS discretionary) “The only thing is my own value set, it’s getting a bit high, I don’t really like that idea. I’ll have to circle it anyway. That’s where I found the difficulty. Down here was easy because it’s nice, I’m feeling okay about that.”—Mother 11 (CDQ discretionary) |

| Response Strategy | Definition | Example Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Enumeration | Parent explicitly counted the number of times the child ate a particular food. | “She had them the day before, so that’s 1, and then Friday she didn’t have them. Thursday I think she had them before school, so that’s 2, and I bought them on Tuesday night and she probably had them Wednesday morning, so that’s 3.”—Mother 9 (CDQ discretionary) |

| Rate retrieval | Parent directly recalled the rate from memory, as opposed to estimating it. | “I’d go 7 to cover breakfast for sure. We always have cereal.”—Mother 2 (PDQ grain) |

| Rate estimation | Parent actively generated the rate, as opposed to directly retrieving it from memory. | “So, I’d say probably on average, maybe two times a week.”—Mother 9 (SFS meat) |

| Rate and adjustment | Parent indicated use of rate information (either though rate retrieval or rate estimation) but then adjusted the rate up or down to account for exceptions. | “Well, if I think about the day she’s at home with me on a Friday then it kinda probably goes up a little bit to maybe to 16 rather than 14”—Mother 1 (SFS grain) |

| General impressions | Parent first used language related to the magnitude of their child’s liking of a food, then converted that subjective impression to a specific rate. | “He loves cucumber…he would have that more than five times”—Mother 11 (PDQ vegetables) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zarnowiecki, D.; Byrne, R.A.; Bodner, G.E.; Bell, L.K.; Golley, R.K. Improving the Reporting of Young Children’s Food Intake: Insights from a Cognitive Interviewing Study with Mothers of 3–7-Year Old Children. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1645. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12061645

Zarnowiecki D, Byrne RA, Bodner GE, Bell LK, Golley RK. Improving the Reporting of Young Children’s Food Intake: Insights from a Cognitive Interviewing Study with Mothers of 3–7-Year Old Children. Nutrients. 2020; 12(6):1645. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12061645

Chicago/Turabian StyleZarnowiecki, Dorota, Rebecca A. Byrne, Glen E. Bodner, Lucinda K. Bell, and Rebecca K. Golley. 2020. "Improving the Reporting of Young Children’s Food Intake: Insights from a Cognitive Interviewing Study with Mothers of 3–7-Year Old Children" Nutrients 12, no. 6: 1645. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12061645

APA StyleZarnowiecki, D., Byrne, R. A., Bodner, G. E., Bell, L. K., & Golley, R. K. (2020). Improving the Reporting of Young Children’s Food Intake: Insights from a Cognitive Interviewing Study with Mothers of 3–7-Year Old Children. Nutrients, 12(6), 1645. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12061645