Abstract

This study aims to explore associations between emotional eating, depression and laryngopharyngeal reflux among college students in Hunan Province. Methods: This cross-sectional study was conducted among 1301 students at two universities in Hunan. Electronic questionnaires were used to collect information about the students’ emotional eating, depressive symptoms, laryngopharyngeal reflux and sociodemographic characteristics. Anthropometric measurements were collected to obtain body mass index (BMI). Results: High emotional eating was reported by 52.7% of students. The prevalence of depressive symptoms was 18.6% and that of laryngopharyngeal reflux symptoms 8.1%. Both emotional eating and depressive symptoms were associated with laryngopharyngeal reflux symptoms (AOR = 3.822, 95% CI 2.126–6.871 vs. AOR = 4.093, 95% CI 2.516–6.661). Conclusion: The prevalence of emotional eating and depressive symptoms among Chinese college students should be pay more attention in the future. Emotional eating and depressive symptoms were positively associated with laryngopharyngeal symptoms. The characteristics of emotional eating require further study so that effective interventions to promote laryngopharyngeal health among college students may be formulated.

1. Introduction

Emotional eating (EE) has been defined as “the tendency to eat in response to a range of negative emotions such as anxiety, depression, anger and loneliness, to cope with negative affect” [1]. In a survey conducted in Finland, 25%–30% of people reported choosing to eat in response to stress [2]. Over the past few decades, the number of individuals with EE has increased significantly [3] and EE is associated with an increase of negative emotions such as depression, stress and anxiety in the population. In China, approximately 23.8% of first-year college students have depressive symptoms [4], The prevalence of depressive symptoms is increasing [5]. With increasing levels of various negative emotions, the number of individuals with EE will gradually increase. Dietary changes caused by negative emotions and emotional eating are often increased intake of high energy density foods, such as sugary foods, sweets or fried foods, etc. [6], which may lead to obesity and increase the risk of chronic diseases [7]. Emotional eating has been linked to overeating and/or fast-eating [8]. These eating habits bring extra burdens on the digestive system. However, few studies have clarified the effects of depression or EE on digestive tract function.

Digestive function is closely related to a daily diet. Studies have shown that continuous eating and anorexia nervosa, binge-eating–purging type can increase the risk of acid reflux [9,10]. Negative emotions and EE may increase the risk of eating disorders such as overeating and binge-eating [11]. Laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR), a type of gastric acid reflux, is described as retrograde reflux of gastro-duodenal contents into the larynx and pharynx, leading to severe damage of the upper aerodigestive tract [12]. About 5% of people in the Chinese population have LPR [13]. LPR can cause severe head and neck diseases such as hoarseness, taste damage, tooth erosion and cancer [14,15,16,17,18]. To date, the pathogenesis of LPR has not been wholly elucidated [19]. Depression, alcoholism, fermented food, and overeating may increase the risk of LPR [20,21,22]. It is well known that EE behavior can lead to overeating or eating disorders [8]. Studies have also shown that EE was associated with high intakes of high-density snack foods [6]. High fat consumption was associated with an increased risk of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms [23]. Hence, we are wondering: Is LPR, which similar to GERD, also related to dietary intake? Is emotional eating a risk factor for LPR?

Although studies have explored the relationship between dietary intake and GERD [23,24,25], few have investigated the association between diet and LPR symptoms. The damage of negative emotions and EE on the upper aerodigestive tract function is unknown. LPR and gastroesophageal reflux are both acid refluxes. The response of the larynx differs from that of the esophagus in acid reflux. Because the larynx lacks defense mechanisms to protect against damage by refluxate present in the throat, chronic laryngeal inflammation caused by LPR may trigger neoplastic lesion [26]. To date, the risk factors of LPR symptoms have not been completely elucidated. If diet or psychological factors related to LPR can be identified, and appropriate interventions made, LPR disease may be prevented. Therefore, this study aims to investigate both the prevalence of LPR and the relationship between depressive symptoms, EE and LPR symptoms among first-year college students. It will provide a reference for interventions of EE and depression and contribute to the understanding of LPR.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

In this cross-sectional study, participants were recruited from two universities in Changsha, Hunan Province, China between May and September 2019. Recruitment was targeted at first-year students and second-year students. The inclusion criteria for participants are summarized as follows: (1) undergraduate students enrolled in 2017 or 2018; (2) capable of providing informed consent and willingness to participate in the study; (3) able to read and fully comprehend the questionnaires items well. Exclusion criteria: current active infection or acute illness of any kind.

No study has investigated the prevalence of EE in Chinese college students. According to the results of similar surveys in other countries, approximately 39% of adults are high emotional eaters (prevalence among man is lower than among woman) [6]. The required sample size was 1047, as calculated using PASS software (version 11.0 for Windows; NCSS LLC, Kaysville, UT, USA), with an expected prevalence of high emotional eaters of 31.6% and an allowable error of 3%. A total of 1307 students were recruited; students who did not complete the questionnaires or unreliable questionnaires (for example, frequencies of all the food categories were reported as “never”), resulting in a sample of 1301 participants. The study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the Xiangya School of Public Health, Central South University (No. XYGW-2019-026). Electronic informed consent was obtained from each participant.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Questionnaire Survey

We used cluster sampling to collect samples from Central South University and Hunan Normal University. Data were collected through Questionnaire Star in a class room situation after informed consent was obtained. The Questionnaire Star is a tool used to develop electronic questionnaires. Each questionnaire had a unique QR code, that could be scanned by the WeChat or QQ app on a smartphone [27]. Two methods were employed to collect samples: (1) asking lecturers to inform students about the survey; and (2) posting posters on campus and sharing copies with WeChat and QQ groups to students to participate at the designated time and place. In addition to demographics information, EE, depressive symptoms, physical activity, LPR symptoms, and food consumption were assessed by the way.

Demographic characteristics: Each student’s sex, age, ethnicity, sibling status (only child, (yes vs. no), place of residence, academic major and monthly living expenses.

Emotional eating: Emotional eating refers to the tendency to eat in a negative emotional state [28]. Emotional eating was assessed using the Chinese version of three-factor eating questionnaire (TFEQ-R18V3) [28], which revised by TFEQ-R21 among Chinese college students [29].The revised Chinese version has good reliability and validity among college students [28]. The TFEQ-R18 uses a 4-point response scale for 18 items, 6 of measure EE, with a score ranging from 6 to 24. Cronbach’s alpha for the EE construct was 0.919. The raw scale scores are transformed to a 0–100 scale ((raw score−lowest possible raw score)/possible raw score range) × 100. Higher scores in the respective scales are indicative of more intense EE. This study referred to the classification method of Camilleri et al., and EE scores were categorized based on the sex-specific median cut-points (excluding those with no EE): (1) no EE (score = 0); (2) low EE (0 < score < median); and (3) high EE (score ≥ median) [6].

Depressive symptoms: Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) was used to assess depressive symptoms [30]. The PHQ-9 consists of 9 items on a 4-point response scale (from 0, never, to 3, almost every day). PHQ-9 score ranges from 0 to 27, with a lower score corresponding to fewer depressive symptoms. Scoring is classified as <10 as having no depressive symptoms, ≥10 representing depressive symptoms [30]. The Cronbach α reliability coefficient of the items was 0.887 in this study.

Physical activity: The short form self-administered instruments of the international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ) were used to assess physical activity [31]. We used the instructions provided in the IPAQ manual for reliability and validity, which are detailed elsewhere [32]. We used an overall index of metabolic equivalent (MET, min/week) to present the intensity of physical activity. We used the recommended categorical scoring, three levels of PA (low, moderate and high) as proposed in the IPAQ Scoring Protocol (short form) [32]. Physical activity levels were divided into three grades: low activity or inactivity, moderate physical activity and high physical activity.

Laryngopharyngeal reflux symptoms: Symptoms were assessed using the reflux symptom index (RSI) [33,34], which is getting increasingly recognized by otolaryngologists [35]. The RSI consists of 9 items on a 6-point response scale (from 0, No problem, to 5, severe problem). RSI scores range from 0 to 45; the higher the RSI score, the more severe the LPR symptoms. Scoring is classified as 0–13 as having no LPR symptoms or >13 representing LPR symptoms [33]. Cronbach’s alpha of this test was 0.910.

Food consumption: We used the food frequency questionnaires (FFQ) with 32 food items to measure food consumption during the previous 12 months. According to the dietary characteristics of college students, the FFQ was modified on the basis of Weng et al. [36]. The consumption frequency of sweet and/or fatty foods and salty fatty foods were calculated. Sweet and/or fatty foods include cake, cookies and chocolate, while salty fatty foods include fried chicken, hamburgers and processed meat. Consumption frequencies were categorized by ≥3 times/week or <3 times/week.

2.2.2. Anthropometric Measurements

The height and weight of each participant were measured by TANITA human body composition analyzer BC-W02C (Guangdong Food and Drug Administration (prospective), no. 2210704, 2014), to calculate body mass index (BMI kg/m2). According to the BMI standard for Chinese adults, the healthy BMI range is 18.5–23.9 kg/m2. Those lower than the healthy range are underweight, those 24.0–27.9 kg/m2 are overweight and those higher than 28.0 kg/m2 are obese.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

SPSS 18.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical descriptions, chi-squared tests and logistic regression analyses. The chi-squared test was used to assess differences in the EE and depressive symptoms (with demographic data) and to assess the relationship between EE and, depressive symptoms and LPR symptoms. The participants were classified into LPR symptoms (RSI score > 13) and no LPR symptom (RSI score 0–13). Multiple logistic regression was performed for two models, to examine the variables associated with LPR symptoms, and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed from these models. Odds ratios (OR) were estimated, adjusting for sex, age, body mass index, physical activity, major, depressive symptoms and emotional eating (Model 1); adjusting for Model 1 + sweet and/or fatty foods + salty fatty foods (Model 2). The prevalence of EE, depressive symptoms, and LPR symptoms are expressed as a percentage of N (%). The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Participants

A total of 1301 undergraduate students participated in this survey. Of these, 61.0% were female. Ages ranged from 17 to 25 years (mean = 19.8; SD = 0.9) and a plurality (46.6%) were 19 years old. Mean BMI was 21.4 kg/m2 (SD = 3.9), which was higher among men (22.5 ± 4.0 kg/m2) than females 20.8 ± 3.6 (20.8 ± 3.6 kg/m2, p < 0.001). In all, 45.7% of the students were an only child and 53.3% were registered rural residents. Overall, 3.5% were obese, 11.6% were overweight and 16.1% were underweight. The median score of overall MET score was 1386.0 min/week. Less than a fifth of the participants (17.1%) were physically active and 25.0% were physically inactive. Fewer males than females were emotional eaters (high EE: 48.4% vs. 55.4%; p < 0.001). The mean RSI score was 3.69 (SD = 6.1). The prevalence of depressive and LPR symptoms among the students was 18.6% and 8.1%, respectively (Table 1 and Table 2). Regarding the intake of sweet and/or fatty foods and salty fatty foods, 10.1% consumed sweet and/or fatty foods more than three times per week and 6.6% ate more than salty fatty foods per week (Table 3).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants and prevalence of high emotional eating (TFEQ-R18V3 ≥ median) and depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 ≥ 10).

Table 2.

Associations between LPR symptoms and food intake, emotional eating and depressive symptoms (reflux symptom index (RSI) > 13).

Table 3.

Dietary intake and emotional eating in college students.

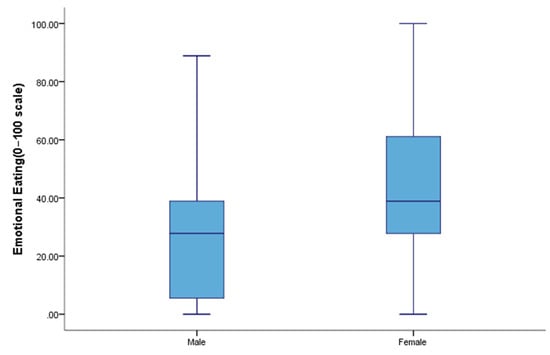

Emotional eating scores varied significantly by major, physical activity levels, BMI, depressive symptoms and LPR symptoms. Females (median = 38.89, 27.78–61.11) had higher EE scores than males (median = 27.78, 5.56–38.89) (p < 0.001) (Figure 1). College students whose major was a liberal art (p < 0.05), with higher BMI (p < 0.01) and with low physical activity levels (p < 0.01) had higher EE scores. Of the those with depressive symptoms, 67.8% had higher EE scores, which was significantly higher than for those who did not have report depressive symptoms (49.2%) (p < 0.001) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Emotional eating scores by sex.

3.2. Association between LPR Symptoms, Food Intake, Emotional Eating and Depressive Symptoms

In this study, the prevalence of LPR symptoms was 8.1% in college students. Individuals reporting high EE had higher scores for LPR symptoms than those with no EE or low EE (12.4% vs. 3.2%, p < 0.001). Students with depressive symptoms showed more LPR symptoms, compared those without depressive symptoms (21.5% vs. 5.0%, p < 0.001). Compared to low consumption, both high consumption of sweet and/or fatty foods (24.2% vs. 6.2%, p < 0.001) and high consumption of salty fatty foods (24.4% vs. 6.9%, p < 0.001) were associated with higher LPR symptoms (Table 2).

We also observed the association between dietary intake and emotional eating among college students. Among both boys and girls, high EE was associated with the consumption of sweet and/or fatty foods (males: 17.1% vs. 6.5%, p < 0.001; females: 11.8% vs. 5.9%, p = 0.004). Only for females, high EE was associated with the intake of salty fatty foods (5.9% vs. 2.8% vs. 11.5%, p = 0.005). For both sexes, depressive symptoms were associated with higher consumption of both sweet and/or fatty foods (17.4% vs. 8.5%, p < 0.001) and salty fatty foods (12.8% vs. 5.2%, p < 0.001) (Table 3).

Multivariate logistic regression models were used to analyze the relationships between LPR symptoms as the dependent variable, EE and depressive symptoms. In model 1, compared with college students with no EE, those with high EE were more likely to have higher LPR symptoms scores (AOR = 4.219, 95% CI 1.273–13.977). Students with depressive symptoms were more likely to have higher LPR symptoms scores than those without depressive symptoms (AOR = 3.600, 95% CI 2.159–6.002). Compared with students with low physical activity, those with moderate physical activity were less likely to report LPR symptoms (AOR = 0.302, 95% CI 0.173–0.528). These associations remained after adjustment for sweet and/or fatty foods. Higher intake of sweet and/or fatty foods was related to higher LPR symptom score (AOR = 3.910, 95% CI 2.168–7.051). There are no significant association between the intake of salty fatty foods and LPR symptom score (Table 4).

Table 4.

Logistic regression analysis of the related factors of LPR symptoms (OR (95% CI)).

4. Discussion

The purpose of our study was to investigate the prevalence of depressive symptoms, emotional eating and LPR symptoms among first-year college students and to explore the relationship between depressive symptoms, EE and LPR symptoms. Our results indicate that the prevalence of LPR symptoms was 8.1% (RSI > 13), which is higher than the investigation in other regions of China (3.1%–5.0%) [13]. Compared with other countries, the prevalence of LPR was higher than in Japan (7.1%) [37] and it was lower than in Greece (18.8%) [38,39]. We used the RSI scale to investigate LPR symptoms. Individuals may experience LPR symptoms, but not yet have reached the diagnostic criteria for LPR disease. A survey found that in the United States, LPR has become a common adult chronic disease [14]. We should pay closer attention to early symptoms associated with LPR, so that we can adopt appropriate interventions and reduce the risk of chronic disease. Compared with patients with GERD patients, those with LPR have different symptoms and pathophysiological mechanisms. Most patients with LPR do not have esophagitis or heartburn, but feel discomfort in larynx area [26], so it is not always easy to associate LPR symptoms with dietary habits. In addition, because the larynx lacks the epithelial defense mechanism available to esophagus, protecting itself from acid attacks is difficult [26], which may result in severe head and neck diseases [14,15,16,17,18]. Therefore, greater attention should be paid to LPR. Many studies have uncovered that certain dietary habits are related to LPR, such as fermented foods [20] and excessive drinking [22]. In addition, some studies have suggested that certain diets, such as low-acid, and plant protein diets have positive effects in the treatments of LPR [15,40]. Studies have also found that low-fat diets are helpful in the treatment of esophageal reflux disease [41]. In this study, we determined that the frequency of high-sweet/high-fat intake was positively associated with LPR. Therefore, we suspect that reducing the intake of high-energy foods can prevent LPR disease. What is more, moderate physical activity was benefit for reducing of LPR symptoms.

Laryngopharyngeal reflux was a controversial topic due to inconsistencies in epidemiological and etiological data [42]. Previous studies have shown that certain eating behaviors, such as the intake of carbonated beverages, meals and chocolate may damage esophageal function or trigger gastric acid secretion [43,44] However, few studies have explored the association between negative emotions and EE and LPR symptoms. In the present study, we found that depressive symptoms and EE was positively associated with LPR symptoms. Emotional eating refers to a tendency to eat when negative emotions are present. High-level EE (i.e., the group with a high EE score) was likely to reflect two performances when individual eats. First is, the propensity to overeat or binge-eating when experiencing negative emotions [8]. Studies have demonstrated that overeating behavior, such as eat-all-the-time or eat-too-full was a risk factor for LPR and acid reflux [10,45]. Acid secretion increases with increased gastric content. Serious eating disorders, such as binge-eating with self-induced vomiting, may risk incidence of acid reflux [18,46]. Eventually, gastric acid attacks the larynx and triggers various LPR symptoms. Second, the food consumption of emotional eaters differs from others. In our study, individuals with high EE scores consumed high-energy foods more frequently, and high-energy foods were positively associated with LPR symptoms. Few studies have reported the relationship between food consumption and LPR disease, but one study suggested that high dietary fat intake is associated with an increased risk of GERD symptoms and erosive esophagitis [23].

Negative emotions and depressions are related to various digestive diseases [47]. Similar to the findings of other studies, our findings signified an association between depressive symptoms and LPR symptoms [48]. However, many studies have found that individuals with gastrointestinal disorders were more likely to be depressed [49]. Longitudinal studies would be valuable in clarifying the causal relationship between depression and LPR. According to our results, depression and EE are related to LPR symptoms. LPR can increase depressive symptoms and then negative emotions aggravate LPR symptoms by changing dietary behaviors. As a result, a vicious circle may form. Further research is needed to confirm these results. In summary, the association between LPR and dietary behaviors cannot be ignored. Whether with patients with LPR individuals with LPR symptoms, detection as early as possible is crucial, EE may be effectively limited by appropriate interventions, such as the mindfulness [50], physical activity [51] or other intervention methods [52].

The prevalence of depressive symptoms in our study was 18.6%, slightly higher than was reported by Feng et al. [53]—and similar to the results of a systematic review in China [54]—but it was lower than in other countries (30.6%) [55]. Although college students are able to acquire a better education, they have a higher risk of depression than other groups around the world [55,56,57,58]. With increasing depression, EE is increasing [58]. Emotional eating has increased significantly in the past 20 years [3]. In our study, numerous students had high EE scores. In our study, we used the median (0–100) to represent emotional eating score, and the results were similar to the adults in other countries [59,60], indicating that EE was high among these students. However, some studies use mean values to represent EE scores [61,62,63]. It is necessary to inform the EE level of a unified evaluation standard for comparison. Psychological factors affect eating behaviors, and both are determinants of physical health. In China, people are beginning more attention to eating behaviors and psychological problems. We require additional evidence to clarify the associations between negative emotions, unhealthy eating behaviors and LPR symptoms.

No differences in depressive symptoms for sex or academic major were identified. However, lower monthly living expenses, low physical activity and high physical activity were positively associated with depressive symptoms, which is similar to other studies [64]. Socioeconomic conditions are a common influencing factor for depression. Reasonable exercise frequency is beneficial for the reduction of negative emotions in college students. Heavier people had higher EE scores, as in other studies [65]. However, the causal relationship between EE and overweight and obesity is unclear. Longitudinal studies have suggested that EE may increase weight [57,58]. Weight gain can also cause depression [65], which may lead to higher levels of EE [66]. Therefore, high emotional eaters should be identified as early as possible so that they can be guided to form a healthy diet, which can effectively control obesity and reduce the incidence of chronic diseases. In this study, medical students and students with higher physical activity reported lower EE scores, perhaps because they were more health-conscious than others [67,68]. Improved health education in early life may prevent college students from developing EE when they are older.

We recruited a sufficient sample. Moreover, the tool of this investigation was electronic questionnaire, and participants had to complete it before submitting it, which ensured the integrity of the questionnaire data. For the first time, we identified an association between depressive symptoms and EE with LPR symptoms. However, the study had limitations. First, the population in our study cannot reflect the prevalence of EE, depressive and LPR symptoms among all Chinese college students. Second, the cross-sectional design of the study does not allow to infer any direction of causality among the studied variables. Third, although we used the TFEQ-R18 V3 scale to quantify EE, we did not know the specific number of occurrences of EE in the prior period. In other words, even if a participant had a high EE score, it is uneasy to determine whether their food consumption changed if they had not experienced negative emotions. Fourth, this study does not include quantitative data of dietary intake (e.g., calories, sugar and fat). Future study should include the information of period of emotional eating and dietary survey, for a better understanding of dietary intake of people with emotional eating. At the same time, a prospective study of a large population should be conducted to clarify the association between EE and LPR or other diseases. The results of this study can provide a rough picture of the prevalence of EE, depressive symptoms and LPR symptoms among college students in China and can help improve student’s health perceptions and dietary behaviors. More important, it may provide a reference for the guidance of LPR interventions.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we found emotional eating and depressive symptoms were associated with LPR symptoms. The prevalence of high EE, depressive symptoms, and LPR symptoms were 52.6%, 18.6% and 8.1% among college students; We should adopt reasonable measures to reduce emotional eating, unhealthy eating habits and depression to prevent LPR disease.

Author Contributions

Q.L. contributed to the conception and design of the study; Q.L. and H.L. drafted the protocol, applied for grant funding for the study and revised the protocol and helped contact school administrators; H.L., Q.Y., J.L., Y.O., C.X., M.S., Y.X. and C.Y. participated in investigations and data collection; H.L. was responsible for data cleaning and analysis; H.L. wrote the first draft and final article versions of this study. All authors interpreted the results and made a substantial contribution to the manuscript’s improvement. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China 81903404.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the teachers and participants in these two university. We also thank the teachers and students from the Xiangya School of Public Health, Central South University, in Changsha, China, for their assistance in executing this investigation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Arnow, B.; Kenardy, J.; Agras, W. The emotional eating scale: The development of a measure to assess coping with negative affect by eating. Int. J. Eat. Disorder. 1995, 18, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitinen, J.; Ek, E.; Sovio, U. Stress-Related Eating and Drinking Behavior and Body Mass Index and Predictors of This Behavior. Prev. Med. 2002, 34, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Strien, T.; Herman, C.P.; Verheijden, M.W. Eating style, overeating, and overweight in a representative Dutch sample. Does external eating play a role? Appetite 2009, 52, 380–387. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, T.; Wu, D.; Zhang, W.; Cottrell, R.R.; Rockett, I.R. Comparative stress levels among residents in three Chinese provincial capitals, 2001 and 2008. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48971. [Google Scholar]

- Acharya, L.; Jin, L.; Collins, W. College life is stressful today—Emerging stressors and depressive symptoms in college students. J. Am. Coll. Health. 2018, 66, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, G.M.; Méjean, C.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Andreeva, V.A.; Bellisle, F.; Hercberg, S.; Péneau, S. The associations between emotional eating and consumption of energy-dense snack foods are modified by sex and depressive symptomatology. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 1264–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geliebter, A.; Aversa, A. Emotional eating in overweight, normal weight, and underweight individuals. Eat. Behav. 2003, 3, 341–347. [Google Scholar]

- Lindeman, M.; Stark, K. Emotional Eating and Eating Disorder Psychopathology. Eat. disord. 2001, 9, 251–259. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, K.; Mehler, P.S. Medical complications of bulimia nervosa and their treatments. Eat. Weight Disord. Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2016, 21, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, N. Don’t change. Women’s Health 2007, 4, 100. [Google Scholar]

- Ricca, V.; Castellini, G.; Lo Sauro, C.; Ravaldi, C.; Lapi, F.; Mannucci, E.; Rotella, C.M.; Faravelli, C. Correlations between binge eating and emotional eating in a sample of overweight subjects. Appetite 2009, 53, 418–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koufman, J.A. The Otolaryngologic Manifestations of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD): A Clinical Investigation of 225 Patients Using Ambulatory 24-Hour pH Monitoring and an Experimental Investigation of the Role of Acid and Pepsin in the Development of Laryngeal Injury. Laryngoscope 1991, 101, 1–78. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.M.; Li, Y.; Guo, W.L.; Wang, W.T.; Lu, M. Prevalence of laryngopharyngeal reflux disease in Fuzhou region of China. Zhonghua er bi yan hou tou jing wai ke za zhi = Chin. J. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016, 51, 909–913. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, N.; Dettmar, P.; Strugala, V.; Allen, J.; Chan, W. Laryngopharyngeal reflux and GERD. Ann. Ny. Acad. Sci. 2013, 1300, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zalvan, C.H.; Hu, S.; Greenberg, B.; Geliebter, J. A Comparison of Alkaline Water and Mediterranean Diet vs. Proton Pump Inhibition for Treatment of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2017, 143, 1023–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altundag, A.; Cayonu, M.; Salihoglu, M.; Yazıcı, H.; Kurt, O.; Yalcınkaya, E.; Saglam, O. Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Has Negative Effects on Taste and Smell Functions. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. Off. J. Am. Acad. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016, 155, 117–121. [Google Scholar]

- Imfeld, C.; Imfeld, T. Reflux disease and eating disorders—A case for teamwork. Therapeutische Umschau. Revue Therapeutique. 2008, 65, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, R.; Sansone, L. Hoarseness: A Sign of Self-induced Vomiting? Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 9, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q. Progress in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Disease. Ph.D. Thesis, Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kesari, S.P.; Chakraborty, S.; Sharma, B. Evaluation of Risk Factors for Laryngopharyngeal Reflux among Sikkimese Population. Kathmandu Univ. Med. J. (KUMJ) 2017, 15, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Wang, G.; Wu, W.; Liu, H.; Xu, B.; Han, H.; Li, B.; Sun, Z.; Ding, R. Influence of psychological factors on laryngopharyngeal reflux disease. J. Pract. Med. 2019, 35, 3199–3203. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Xu, L.; Lin, Z. Analysis of influencing factors and observation of therapeutic effects in patients with laryngopharyngeal reflux disease. J. Otolaryngol. Ophthalmol. Shandong Univ. 2019, 33, 119–123. [Google Scholar]

- El-Serag, H.B.; Satia, J.A.; Rabeneck, L. Dietary intake and the risk of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: A cross sectional study in volunteers. Gut 2005, 54, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, K.L.; Davies, G.J.; Dettmar, P.W. Diet and lifestyle triggers for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: Symptom identification. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2010, 69, E108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuta, A.; Adachi, K.; Furuta, K.; Ohara, S.; Morita, T.; Koshino, K.; Tanaka, S.; Moriyama, M.; Sumikawa, M.; Sanpei, M.; et al. Different sex-related influences of eating habits on the prevalence of reflux esophagitis in Japanese. J. Gastroen. Hepatol. 2011, 26, 1060–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, L. Laryngopharyngeal reflux—It’s not GERD. JAAPA Off. J. Am. Acad. Phys. Assist. 2005, 18, 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J. Using “Sojump.com”-based Online Testing in Higher Vocational Teaching and Learning. J. Hubei Radio Telev. Univ. 2017, 37, 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Zang, T.; Hao, Y.; Yuan, H.; Bu, P. Validity and reliability of Chinese version of Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire R21 for assessment of sample of college students. Chin. Nurs. Res. 2016, 30, 4137–4141. [Google Scholar]

- Rosnah, I.; Noor Hassim, I.; Shafizah, A.S. A Systematic Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process for Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ-R21). Med. J. Malays. 2013, 68, 424–434. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjöström, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.; et al. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire-: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sport. Exer. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Lyu, J.; He, P. Chinese guidelines for data processing and analysis concerning the International Physical Activity Questionnaire. Chin. Med. J. 2014, 35, 961–964. [Google Scholar]

- Belafsky, P.C.; Postma, G.N.; Koufman, J.A. Validity and reliability of the reflux symptom index (RSI). J. Voice Off. J. Voice Found. 2002, 16, 274–277. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Wu, W.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.; Xu, X.; Xu, B.; Ding, R.; Zhou, Y.; Han, H.; Gong, J.; et al. Correlation analysis between Ryan index and reflux symptom index and reflux finding score, in the diagnosis of laryngopharyngeal reflux diseases. J. Otolaryngol. Ophthalmol. Shandong Univ. 2018, 32, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mallikarjunappa, A.; Deshpande, G. Comparison of Reflux Symptom Index (RSI) with Reflux Finding Score (RFS) and Its Effectiveness in Diagnosis of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Disease (LPRD). Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg 2020, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, T.; Hao, J.; Qian, Q.; Cao, H.; Fu, J.; Sun, Y.; Huang, L.; Tao, F. Is there any relationship between dietary patterns and depression and anxiety in Chinese adolescents? Public Health Nutr. 2011, 15, 673–682. [Google Scholar]

- Sone, M.; Katayama, N.; Kato, T.; Izawa, K.; Wada, M.; Hamajima, N.; Nakashima, T. Prevalence of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Symptoms: Comparison between Health Checkup Examinees and Patients with Otitis Media. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. Off. J. Am. Acad. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2012, 146, 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Xu, M.; Luo, W.; Tang, H.; He, F.; Wu, L.; Zhang, J. Nanjing City. Chin. J. Otorhinolaryngol. Skull Base Surg. 2013, 19, 416–419. [Google Scholar]

- Spantideas, N.; Drosou, E.; Bougea, A.; Assimakopoulos, D. Laryngopharyngeal reflux disease in the Greek general population, prevalence and risk factors. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 2015, 15, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Koufman, J. Low-Acid Diet for Recalcitrant Laryngopharyngeal Reflux: Therapeutic Benefits and Their Implications. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. laryngol. 2011, 120, 281–287. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, M.; Büttner, P.; Harrison, S.; Mccutchan, C. How do dietitians treat symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in adults? Nutr. Diet. 2010, 67, 224–230. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, R.; Sataloff, R.T. Laryngopharyngeal reflux: Current concepts and questions. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngo. 2009, 17, 143–148. [Google Scholar]

- Meining, A.; Classen, M. The role of diet and lifestyle measures in the pathogenesis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2000, 95, 2692–2697. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach, T.; Crockett, S.; Gerson, L.B. Are lifestyle measures effective in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease? An evidence-based approach. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Guo, W.; Wang, W.; Lu, M. Analysis the risk factors and the prevalence of Laryngopharyngeal reflux disease in Fuzhou area. Chin. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2017, 24, 202–206. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, Y.; Fukudo, S. Gastrointestinal symptoms and disorders in patients with eating disorders. Clin. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 8, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.P.; Sung, I.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.; Park, H.S.; Shim, C.S. The effect of emotional stress and depression on the prevalence of digestive diseases. J. Neurogastroenterol. 2015, 21, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamani, T.; Penney, S.; Mitra, I.; Pothula, V. The prevalence of laryngopharyngeal reflux in the English population. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. Off. J. Eur. Fed. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. Soc. (EUFOS): Affil. Ger. Soc. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2012, 269, 2219–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Wang, Q.; Huang, K.; Huang, J.; Zhou, C.; Sun, F.; Wang, S.; Wu, F. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with chronic digestive system diseases: A multicenter epidemiological study. World J. Gastroentero. 2016, 22, 9437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hondorp, S.; Kleinman, B.; Hood, M.; Nackers, L.; Corsica, J. Mindfulness meditation as an intervention for binge eating, emotional eating, and weight loss: A systematic review. Eat. Behav. 2014, 15, 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, A.; Rydell, S.; Eisenberg, M.; Laska, M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Yoga’s potential for promoting healthy eating and physical activity behaviors among young adults: A mixed-methods study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phy. 2018, 15, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, C. Randomized Test of a Brief Psychological Intervention to Reduce and Prevent Emotional Eating in a community sample. J. Public Health (Oxf. Engl.) 2015, 37, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Du, Y.; Ye, Y.; He, Q. Associations of Physical Activity, Screen Time with Depression, Anxiety and Sleep Quality among Chinese College Freshmen. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Xiao, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y. Prevalence of Depression among Chinese University Students: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e153454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.K.; Ibrahim, A.K.; Kelly, S.J.; Adams, C.E.; Glazebrook, C. A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 47, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarasuriya, S.D.; Jorm, A.F.; Reavley, N.J. Prevalence of depression and its correlates among undergraduates in Sri Lanka. Asian J. Psychiatry 2015, 15, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivin, K.; Eisenberg, D.; Gollust, S.E.; Golberstein, E. Persistence of mental health problems and needs in a college student population. J. Affect. Disord. 2009, 117, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, N.; Bilgel, N. The prevalence and socio-demographic correlations of depression, anxiety and stress among a group of university students. Soc. Psych. Psych. Epid. 2008, 43, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péneau, S.; Ménard, E.; Méjean, C.; Bellisle, F.; Hercberg, S. Sex and dieting modify the association between emotional eating and weight status. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 1307–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anglé, S.; Engblom, J.; Eriksson, T.; Kautiainen, S.; Saha, M.; Lindfors, P.; Lehtinen, M.; Rimpelä, A. Three factor eating questionnaire-R18 as a measure of cognitive restraint, uncontrolled eating and emotional eating in a sample of young Finnish females. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phy. 2009, 6, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Konttinen, H.; Haukkala, A.; Sarlio-Lähteenkorva, S.; Silventoinen, K.; Jousilahti, P. Eating styles, self-control and obesity indicators. The moderating role of obesity status and dieting history on restrained eating. Appetite 2009, 53, 131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Blandine de Lauzon-Guillain, B.; Romon, M.; Musher-Eizenman, D.; Heude, B.; Basdevant, A.; Charles, M.A.; Fleurbaix-Laventie, V.S.S.G. Cognitive restraint, uncontrolled eating and emotional eating: Correlations between parent and adolescent. Matern. Child Nutr. 2009, 5, 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Keskitalo, K.; Tuorila, H.; Spector, T.D.; Cherkas, L.F.; Knaapila, A.; Kaprio, J.; Silventoinen, K.; Perola, M. The Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire, body mass index, and responses to sweet and salty fatty foods: A twin study of genetic and environmental associations. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanzadeh Taheri, M.M.; Mogharab, M.; Akhbari, S.H.; Raeisoon, M.R.; Hasanzadeh Taheri, E. Prevalence of depression among new registered students in Birjand University of Medical Sciences in the academic year 2009–2010. Yektaweb 2011, 18, 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, D.; Jaffe, K. The Psychological Consequences of Weight Change Trajectories: Evidence from Quantitative and Qualitative Data. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2012, 10, 419–430. [Google Scholar]

- Van Strien, T.; Engels, R.; Leeuwe, J.; Snoek, H. The Stice model of overeating: Tests in clinical and non-clinical samples. Appetite 2006, 45, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Fu, L.; Niu, B.; Ma, D.; Niu, Q.; Li, G.; Mu, L.; Ding, Y.; Zheng, R.; Feng, G. Nutritional knowledge, attitudes and dietary behavior of college students in Shihezi University. Chin. J. Sch. Health. 2013, 34, 1306–1308. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Yao, Y. Investigation on health literacy and life style of college students in Wuhan. J. Pub. Health Prev. Med. 2011, 22, 31–32. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).