Using Sensory Cues to Optimise the Satiety Value of a Reduced-Calorie Product Labelled ‘Healthier Choice’

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Test Foods

2.3.1. Standard Breakfast

2.3.2. Test Beverages

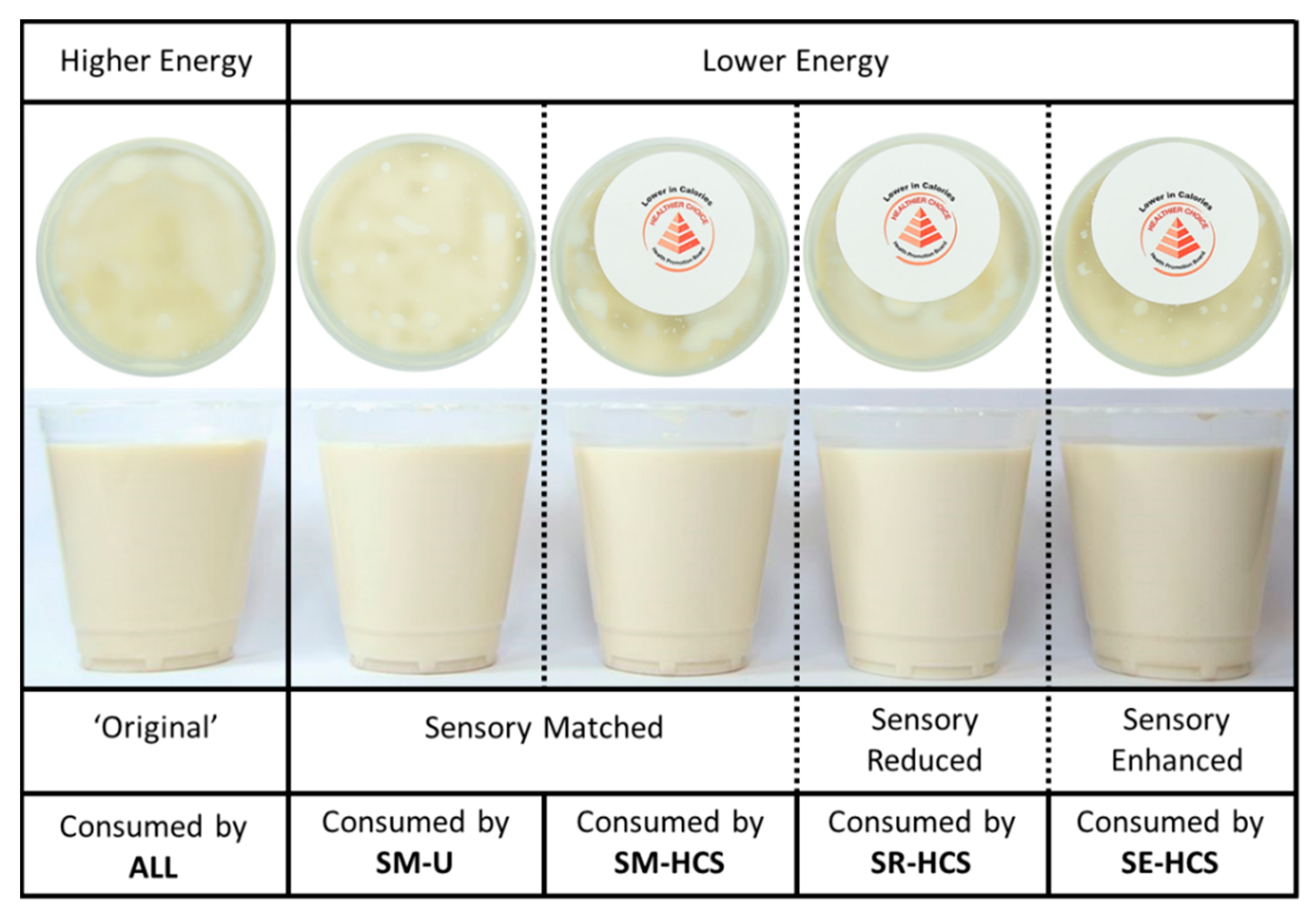

- Sensory-matched unlabelled (SM-U)—Sensory matched to taste like the original (equally sweet, thick and creamy), without a label identifier (covert energy reduction).

- Sensory-matched labelled (SM-HCS)—The same sensory matched beverage as above, but with the HCS attached (explicit energy reduction).

- Sensory-reduced labelled (SR-HCS)—Designed to taste less thick, sweet and creamy than the original, with the HCS attached (explicit energy reduction).

- Sensory-enhanced labelled (SE-HCS)—Designed to taste thicker, creamier and sweeter than the original, with the HCS attached (explicit energy reduction).

2.3.3. Ad Libitum Lunch

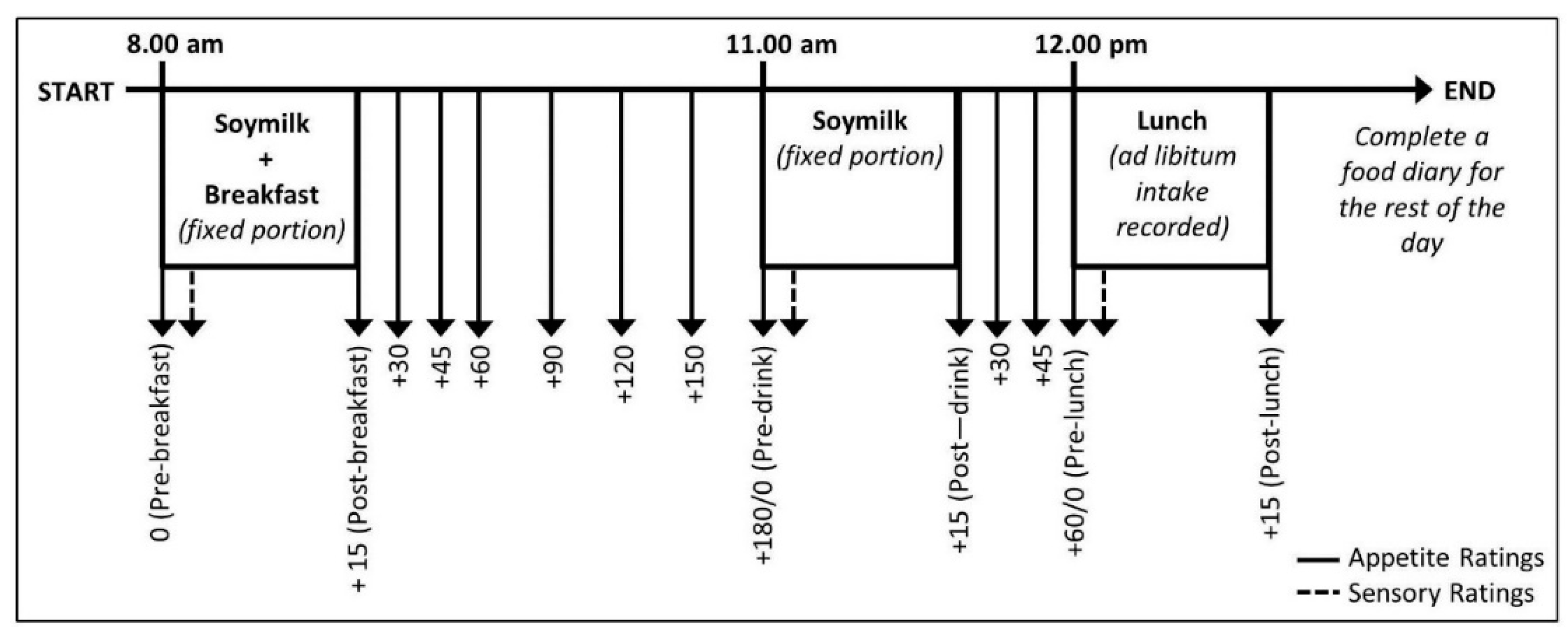

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Sensory and Hedonic Ratings

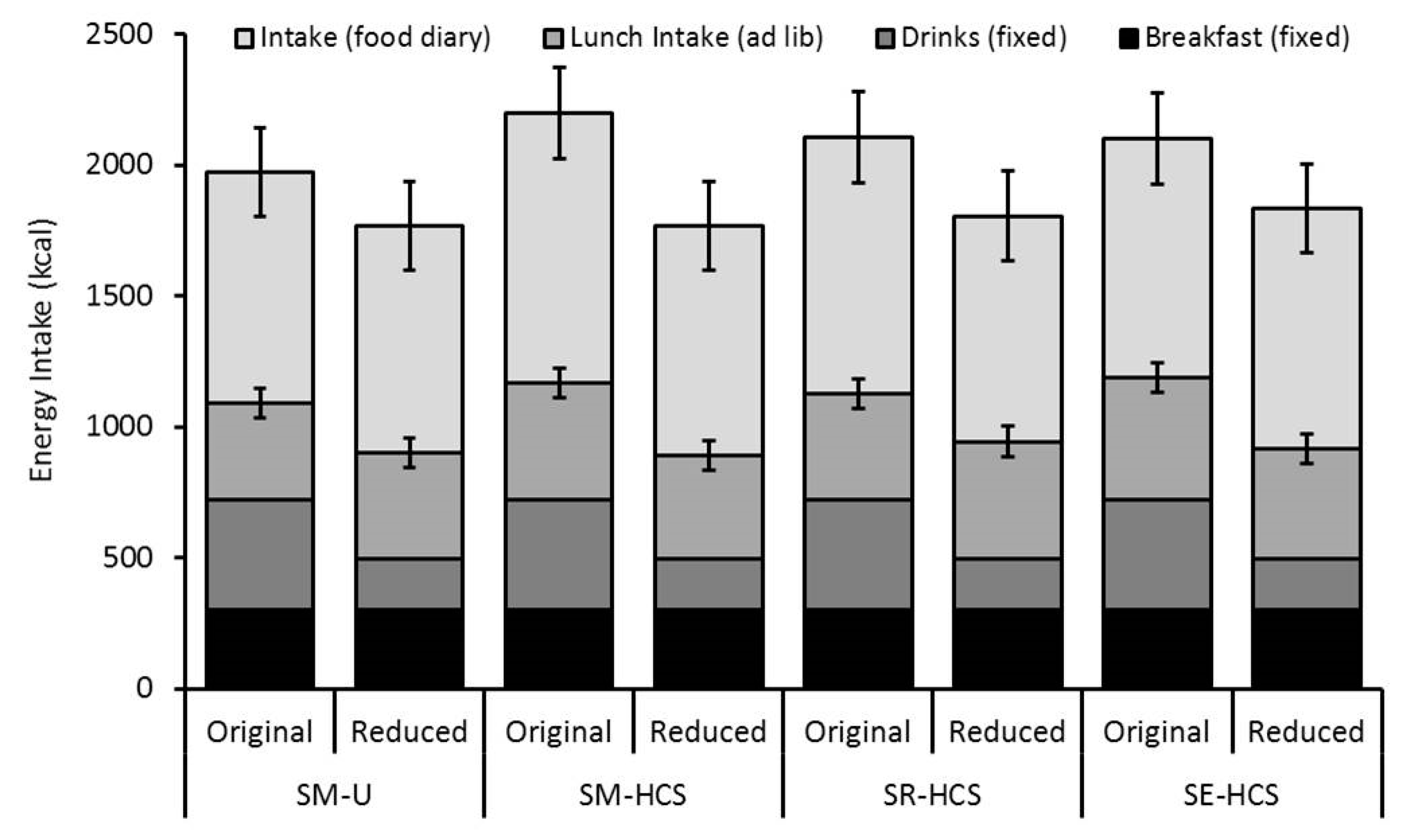

3.3. Energy Intake at Lunch and for the Rest of the Day

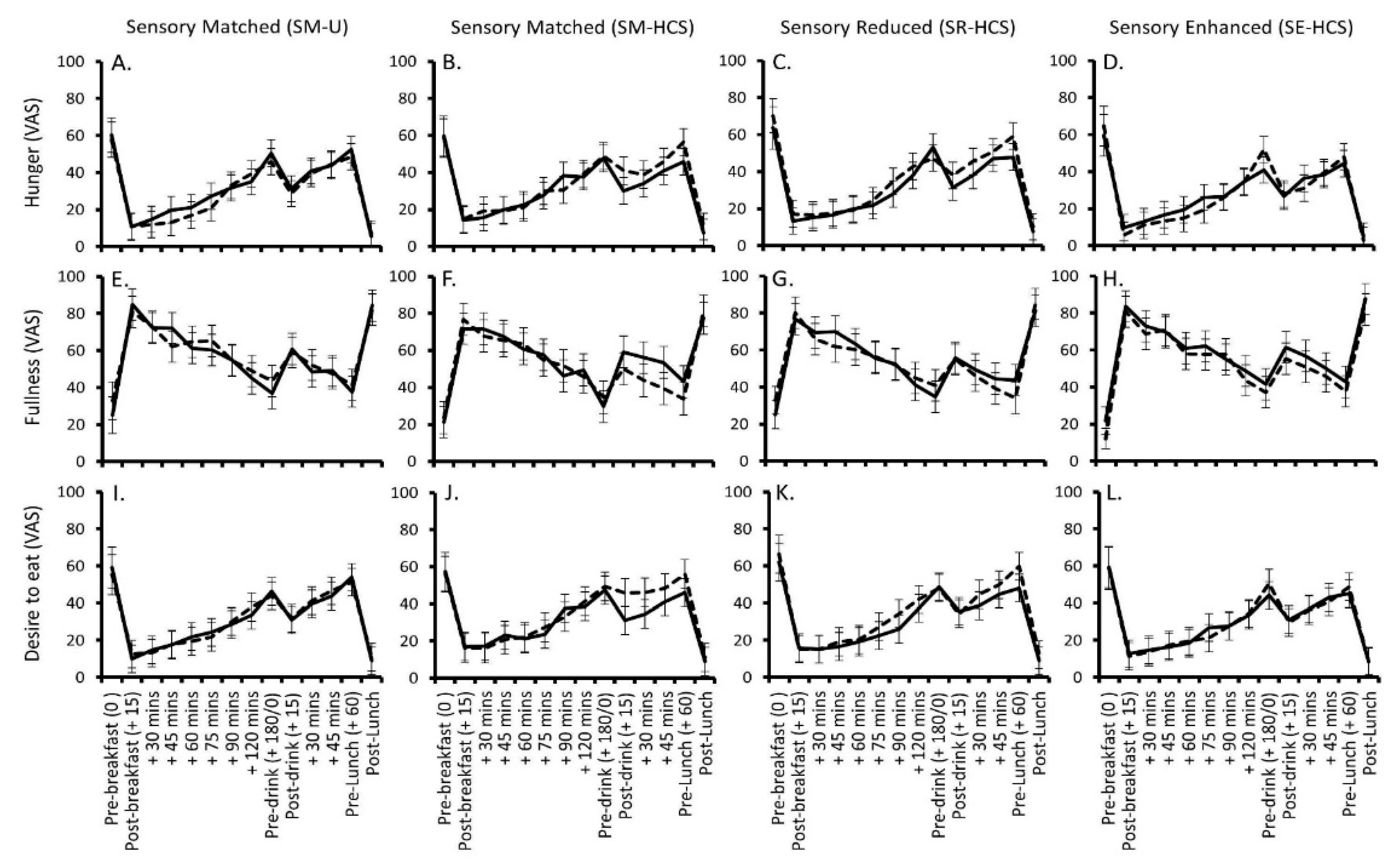

3.4. Changes in Rated Appetite

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Higher Energy a | Lower Energy | Lower Energy | Lower Energy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ingredients | Sensory Matched b | Sensory Reduced c | Sensory Enhanced d | |

| Soymilk (g) 1 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 |

| Maltodextrin (g) 2 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sucralose (g) 3 | 0.0250 | 0.0350 | 0.0100 | 0.0450 |

| Guar gum (g) 4 | 0.20 | 0.45 | 0.20 | 1.00 |

| Vanilla extract (g) 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Cream cheese flavour (g) 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Water (g) | 51 | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| Total energy content (kcal) | 211.1 | 97.5 | 97.1 | 98.4 |

| Total Volume (mL) | 315 | 315 | 315 | 315 |

- There were four different soymilks produced in total (see Appendix A Table A1).

- Participants in the SM-U and SM-HCS groups consumed the same lower energy sensory-matched soymilks, the only difference was whether this was presented with or without the label.

- The final recipes and sensory modifications were derived from two rounds of pilot testing with non-trained panel of participants who did not take part in the main study (n = 17; data not reported).

- The soymilks were refrigerated and served chilled and sealed in plastic cups with the HCS label placed directly on the plastic seal of the relevant beverage.

- The drinks were volume matched to 315 mL portions by the addition of water.

| Breakfast (kcal) | Test Beverages (kcal) | Ad Libitum Lunch Intake (Kcal + 95%CI) | Self-Reported Intake (Kcal + 95%CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SM-U | Original | 299 | 422 | 368 ± 56 | 883 ± 168 |

| Reduced | 299 | 196 | 405 ± 58 | 869 ± 168 | |

| SM-HCS | Original | 299 | 422 | 446 ± 57 | 1031 ± 173 |

| Reduced | 299 | 196 | 395 ± 56 | 876 ± 170 | |

| SR-HCS | Original | 299 | 422 | 407 ± 56 | 978 ± 173 |

| Reduced | 299 | 196 | 445 ± 58 | 862 ± 173 | |

| SE-HCS | Original | 299 | 422 | 467 ± 57 | 915 ± 174 |

| Reduced | 299 | 196 | 423 ± 56 | 917 ± 169 |

References

- Rolls, B.J. The relationship between dietary energy density and energy intake. Physiol. Behav. 2009, 97, 5–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marteau, T.M.; Hollands, G.J.; Shemilt, I.; Jebb, S.A. Downsizing: Policy options to reduce portion sizes to help tackle obesity. BMJ 2015, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Public Health England. Sugar Reduction and Wider Reformulation Collection. 2017. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/sugar-reduction#sugar-reduction (accessed on 31 January 2019).

- Public Health England. Calorie Reduction: The Scope and Ambition for Action. 2018. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/calorie-reduction-the-scope-and-ambition-for-action (accessed on 31 January 2019).

- Hill, J.O.; Wyatt, H.R.; Reed, G.W.; Peters, J.C. Obesity and the Environment: Where Do We Go from Here? Science 2003, 299, 5608–5853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Health and Social Care. Statement of the Calorie Reduction Expert Group; Department of Health and Social Care: London, UK, 2011. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/statement-of-the-calorie-reduction-expert-group (accessed on 31 January 2019).

- Vadiveloo, M.; Parker, H.; Raynor, H. Increasing low-energy-dense foods and decreasing high-energy-dense foods differently influence weight loss trial outcomes. Int. J. Obes. 2018, 42, 3–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetherington, M.M.; Cunningham, K.; Dye, L.; Gibson, E.L.; Gregersen, N.T.; Halford, J.C.G.; Van Trijp, H.C.M. Potential benefits of satiety to the consumer: Scientific considerations. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2013, 26, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, J.D.; Sommer, I. Reducing calorie sales from supermarkets—‘Silent’ reformulation of retailer-brand food products. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, P.J. The role of low-calorie sweeteners in the prevention and management of overweight and obesity: Evidence v. conjecture. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2018, 77, 3–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, P.J.; Hogenkamp, P.S.; De Graaf, C.; Higgs, S.; Lluch, A.; Ness, A.R.; Mela, D.J. Does low-energy sweetener consumption affect energy intake and body weight? A systematic review, including meta-analyses, of the evidence from human and animal studies. Int. J. Obes. 2015, 40, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almiron-Roig, E.; Palla, L.; Guest, K.; Ricchiuti, C.; Vint, N.; Jebb, S.A.; Drewnowski, A. Factors that determine energy compensation: A systematic review of preload studies. Nutr. Rev. 2013, 71, 7–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smethers, A.D.; Roe, L.S.; Sanchez, C.E.; Zuraikat, F.M.; Keller, K.L.; Kling, S.M.; Rolls, B.J. Portion size has sustained effects over 5 days in preschool children: A randomized trial. Physiol. Behav. 2019, 204, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrickerd, K.; Salleh, N.B.; Forde, C.G. Removing energy from a beverage influences later food intake more than the same energy addition. Appetite 2016, 105, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tey, S.L.; Chia, E.M.E.; Forde, C.G. Impact of dose-response calorie reduction or supplementation of a covertly manipulated lunchtime meal on energy compensation. Physiol. Behav. 2016, 165, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gertner, D.; Rifkin, L. Coca-Cola and the Fight against the Global Obesity Epidemic. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 60, 2–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piqueras-Fiszman, B.; Spence, C. Sensory expectations based on product-extrinsic food cues: An interdisciplinary review of the empirical evidence and theoretical accounts. Food Q. Prefer. 2015, 40, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kähkönen, P.; Tuorila, H. Effect of Reduced-fat Information on Expected and Actual Hedonic and Sensory Ratings of Sausage. Appetite 1998, 30, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrickerd, K.; Tang, C.S.; Forde, C.G. The independent and combined impact of front-of-pack labelling and sensory quality on calorie estimations and portion selection of commercial food products. Food Q. Prefer. 2020, 79, 103766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, G.P.; Pourshahidi, L.K.; Wallace, J.M.; Kerr, M.A.; McCaffrey, T.A.; Livingstone, M.B.E. Perceived ‘healthiness’ of foods can influence consumers’ estimations of energy density and appropriate portion size. Int. J. Obes. 2014, 38, 1–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadiveloo, M.; Morwitz, V.; Chandon, P. The interplay of health claims and taste importance on food consumption and self-reported satiety. Appetite 2013, 71, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.M.; Rollo, M.E.; de Vlieger, N.M.; Collins, C.E.; Bucher, T. Influence of the nutrition and health information presented on food labels on portion size consumed: A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2018, 76, 655–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandel, N.; Brannon, D. Sugar, perceived healthfulness, and satiety: When does a sugary preload lead people to eat more? Appetite 2017, 114, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, F.A.; Mattes, R.D. Human dietary responses to perceived manipulation of fat-content in a midday meal. Int. J. Obes. 1993, 17, 4–237. [Google Scholar]

- Appleton, K.M.; Pidgeon, H.J. 5-a-day fruit and vegetable food product labels: Reduced fruit and vegetable consumption following an exaggerated compared to a modest label. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shide, D.J.; Rolls, B.J. Information about the Fat-Content of Preloads Influences Energy-Intake in Healthy Women. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1995, 95, 9–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, L.; Ells, H.; Yeomans, M.R. Can the satiating power of a high energy beverage be improved by manipulating sensory characteristics and label information? Food Q. Prefer. 2013, 28, 1–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, L.; McCrickerd, K.; Yeomans, M.R. Optimising foods for satiety. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 41, 2–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Promotion Board, Singapore. Healthier Choice Symbol Programme. 2018. Available online: https://www.hpb.gov.sg/food-beverage/healthier-choice-symbol (accessed on 1 November 2017).

- McCrickerd, K.; Chambers, L.; Yeomans, M.R. Fluid or Fuel? The Context of Consuming a Beverage Is Important for Satiety. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Promotion Board, Singapore. Food and Nutrient Composition Database. 2011. Available online: https://focos.hpb.gov.sg/eservices/ENCF/ (accessed on 1 November 2017).

- Stunkard, A.J.; Messick, S. The 3-Factor Eating Questionnaire to Measure Dietary Restraint, Disinhibition and Hunger. J. Psychosom. Res. 1985, 29, 1–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, J.P.; Roberts, S.B. Energy Density, Energy Intake, and Body Weight Regulation in Adults. Adv. Nutr. 2014, 5, 6–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandon, P.; Wansink, B. The Biasing Health Halos of Fast-Food Restaurant Health Claims: Lower Calorie Estimates and Higher Side-Dish Consumption Intentions. J. Consum. Res. 2007, 34, 3–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckland, N.J.; Finlayson, G.; Hetherington, M.M. Slimming starters. Intake of a diet-congruent food reduces meal intake in active dieters. Appetite 2013, 71, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lee, H.C.; Chang, C.T.; Cheng, Z.H.; Chen, Y.T. Will an organic label always increase food consumption? It depends on food type and consumer differences in health locus of control. Food Q. Prefer. 2018, 63, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikonen, I.; Sotgiu, F.; Aydinli, A.; Verlegh, P.W. Consumer effects of front-of-package nutrition labeling: An interdisciplinary meta-analysis. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeomans, M.R.; Lartamo, S.; Procter, E.L.; Lee, M.D.; Gray, R.W. The actual, but not labelled, fat content of a soup preload alters short-term appetite in healthy men. Physiol. Behav. 2001, 73, 4–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SM-U (n = 28) | SM-HCS (n = 27) | SR-HCS (n = 28) | SE-HCS (n = 28) | p-Value a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 22.9 ± 1.9 | 23.2 ± 2.4 | 22.8 ± 1.8 | 22.9 ± 1.2 | 0.861 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.7 ± 2.6 | 22.4 ± 2.3 | 22.1 ± 2.4 | 22.3 ± 2.7 | 0.787 |

| Body Fat (%) | 24.2 ± 8.7 | 23.9 ± 5.5 | 23.2 ± 6.1 | 23.5 ± 8.0 | 0.961 |

| Dietary Restraint (0–21) | 8.5 ± 5.3 | 10.7 ± 4.8 | 8.1 ± 5.1 | 8.0 ± 5.1 | 0.178 |

| Consumption Frequency: | |||||

| Soymilk (per week) | 1.0 ± 1.0 | 1.0 ± 1.3 | 1.7 ± 1.9 | 0.9 ± 0.8 | 0.129 |

| Fried rice (per week) | 0.9 ± 0.7 | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 0.8 | 0.7 ± 0.5 | 0.284 |

| Reported using HCS (%) | 64 | 74 | 57 | 57 |

| SM-U (n = 28) | SM-HCS (n = 27) | SR-HCS (n = 28) | SE-HCS (n = 28) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | Reduced | Original | Reduced | Original | Reduced | Original | Reduced | Energy × Context a | |

| Soymilk | |||||||||

| Pleasant | 65.8 ± 6.0 | 68.7 ± 7.1 ns | 76.8 ± 6.2 | 72.2 ± 7.3 ns | 66.4 ± 6.0 | 49.4 ± 7.1 * | 73.1 ± 6.0 | 66.4 ± 7.1 ns | 0.003 |

| Sweet | 56.0 ± 6.6 | 54.4 ± 7.6 ns | 65.8 ± 6.8 | 53.2 ± 7.9 * | 66.6 ± 6.6 | 24.3 ± 7.6 * | 66.6 ± 6.6 | 63.5 ± 7.6 ns | <0.001 |

| Thick | 63.6 ± 7.3 | 57.8 ± 7.6 ns | 67.4 ± 7.5 | 57.2 ± 7.9 * | 57.7 ± 7.3 | 39.6 ± 7.6 * | 63.0 ± 7.3 | 75.0 ± 7.6 ns | <0.001 |

| Creamy | 63.3 ± 7.0 | 61.0 ± 7.6 ns | 65.1 ± 7.3 | 58.2 ± 7.9 ns | 59.0 ± 7.0 | 35.8 ± 7.6 * | 65.9 ± 7.0 | 74.2 ± 7.6 * | <0.001 |

| Familiar | 53.5 ± 8.9 | 61.6 ± 9.5 ns | 65.6 ± 9.2 | 66.3 ± 9.8 ns | 60.6 ± 8.9 | 52.9 ± 9.5 ns | 68.3 ± 8.9 | 41.6 ± 9.5 * | <0.001 |

| Filling | 64.2 ± 8.1 | 64.2 ± 7.6 | 62.9 ± 8.4 | 59.5 ± 7.9 | 53.0 ± 8.1 | 50.4 ± 7.6 | 66.1 ± 8.1 | 71.6 ± 7.6 | 0.335 |

| Lunch | |||||||||

| Pleasant | 56.8 ± 8.0 | 61.0 ± 7.9 | 65.3 ± 8.1 | 70.3 ± 8.0 | 55.9 ± 8.0 | 58.6 ± 7.9 | 61.1 ± 8.0 | 72.5 ± 7.9 | 0.427 |

| Familiar | 50.7 ± 10.3 | 52.1 ± 10.0 | 56.0 ± 10.5 | 61.6 ± 10.2 | 56.9 ± 10.3 | 56.8 ± 10.0 | 60.7 ± 10.3 | 62.8 ± 10.0 | 0.917 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McCrickerd, K.; Tay, P.P.S.; Tang, C.S.; Forde, C.G. Using Sensory Cues to Optimise the Satiety Value of a Reduced-Calorie Product Labelled ‘Healthier Choice’. Nutrients 2020, 12, 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12010107

McCrickerd K, Tay PPS, Tang CS, Forde CG. Using Sensory Cues to Optimise the Satiety Value of a Reduced-Calorie Product Labelled ‘Healthier Choice’. Nutrients. 2020; 12(1):107. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12010107

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcCrickerd, Keri, Priscilla Pei Sian Tay, Claudia Shuning Tang, and Ciarán Gerard Forde. 2020. "Using Sensory Cues to Optimise the Satiety Value of a Reduced-Calorie Product Labelled ‘Healthier Choice’" Nutrients 12, no. 1: 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12010107

APA StyleMcCrickerd, K., Tay, P. P. S., Tang, C. S., & Forde, C. G. (2020). Using Sensory Cues to Optimise the Satiety Value of a Reduced-Calorie Product Labelled ‘Healthier Choice’. Nutrients, 12(1), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12010107