Assessment of Packaged Foods and Beverages Carrying Nutrition Marketing against Canada’s Food Guide Recommendations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Classification of Label Components

2.1.1. Nutrition Information

- List of ingredients: presence/absence of a list of ingredients and other aspects of the list of ingredients (e.g., whether a quantitative ingredient declaration [QUID] was made). The % symbol was searched for in the list of ingredients to verify products with QUID. Products were not considered as displaying QUID if the quantification referred to: % additives (e.g., “contains 2% or less of each of the following: sodium aluminum phosphate, baking soda, artificial flavors, salt), % origin (e.g., “100% Canadian milk”), % organic (e.g., “100% organic ingredients”).

- Nutrient declarations: presence/absence of the Nutrition Facts table.

- Supplementary nutrition information: presence/absence of interpretive nutrition information, such as traffic light labeling (TLL), health star ratings (HSR), or guideline daily amounts (GDA).

2.1.2. Nutrition and Health Claims (i.e., Nutrition Marketing)

- Nutrition claims: including nutrient content claims, nutrient comparative claims and health-related ingredient claims).

- Health claims: including general health claims, nutrient and other function claims, and reduction of disease risk claims). Logos or heart-shaped symbols (such as the ones used by national heart foundations like the British Heart Foundation or the Australia/New Zealand Heart Foundation Tick) were considered as reduction of disease risk claims because they seem to imply a relationship between the consumption or a product and cardiovascular disease risk [44]. In Canada, a similar symbol was used at the time of data collection (the Heart and Stroke Foundation [HSF] logo) and therefore was classified as such for the propose of this study; however, it is important to note that the logo did not comply with the Canadian regulations for disease risk reduction claims and therefore it could instead be considered as an unregulated general health claim. The HSF logo was discontinued in 2014 (a year after data was collected).

- Other claims: included other health-related claims (e.g., “gluten-free” claims) and environment-related claims (e.g., “organic”), but they were not analyzed in the present study as they are not considered “nutrients”.

2.2. Food Category Classification

2.3. Classification of Products According to Health Canada Surveillance Tool Nutrient Profiling System

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Label Components

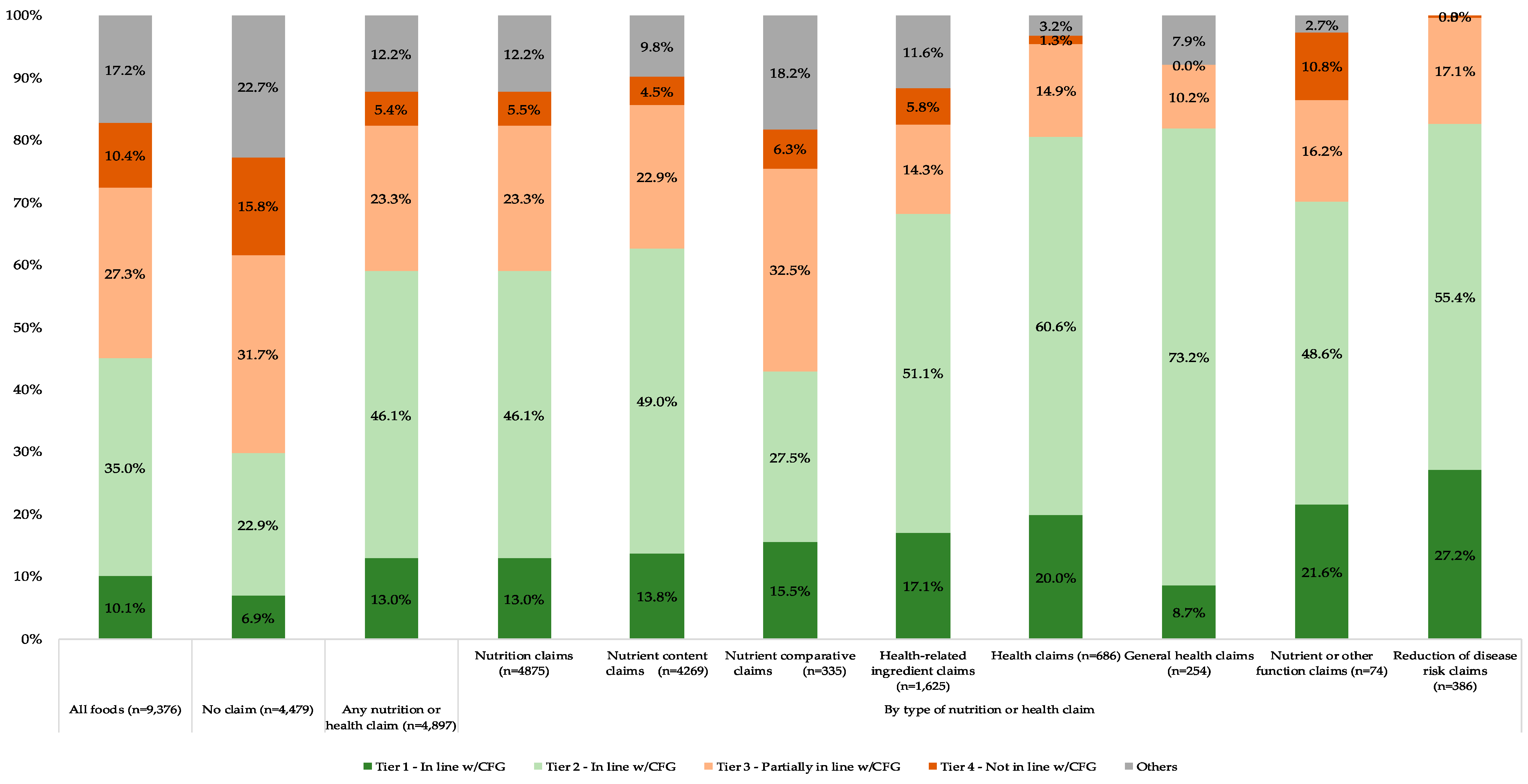

3.2. Proportion of Foods and Beverages in Each Tier

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/94384/1/9789241506236_eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Nikolic, I.A.; Stanciole, A.E.; Zaydman, M. Chronic Emergency: Why NCDS Matter; The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, S.S.; Hawkes, C.; de Souza, R.J.; Mente, A.; Dehghan, M.; Nugent, R.; Zulyniak, M.A.; Weis, T.; Bernstein, A.M.; Krauss, R.M.; et al. Food consumption and its impact on cardiovascular disease: Importance of solutions focused on the globalized food system: A report from the workshop convened by the world heart federation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 66, 1590–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Fact Sheet: Healthy Diet. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines. Available online: http://www.fao.org/nutrition/nutrition-education/food-dietary-guidelines (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Bechthold, A.; Boeing, H.; Tetens, I.; Schwingshackl, L.; Nöthlings, U. Perspective: Food-based dietary guidelines in Europe-scientific concepts, current status, and perspectives. Adv. Nutr. 2018, 9, 544–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montagnese, C.; Santarpia, L.; Iavarone, F.; Strangio, F.; Caldara, A.R.; Silvestri, E.; Contaldo, F.; Pasanisi, F. North and south American countries food-based dietary guidelines: A comparison. Nutrition 2017, 42, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jessri, M.; Lou, W.Y.; L’Abbé, M.R. The 2015 dietary guidelines for americans is associated with a more nutrient-dense diet and a lower risk of obesity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 1378–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jessri, M.; Ng, A.P.; L’Abbé, M.R. Adapting the healthy eating index 2010 for the canadian population: Evidence from the Canadian national nutrition survey. Nutrients 2017, 9, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assmann, K.E.; Andreeva, V.A.; Camilleri, G.M.; Verger, E.O.; Jeandel, C.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Dietary scores at midlife and healthy ageing in a French prospective cohort. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 116, 666–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, B.; Russell, J.; Kifley, A.; Flood, V.M.; Mitchell, P. Adherence to dietary guidelines and successful aging over 10 years. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2016, 71, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voortman, T.; Kiefte-de Jong, J.C.; Ikram, M.A.; Stricker, B.H.; van Rooij, F.J.A.; Lahousse, L.; Tiemeier, H.; Brusselle, G.G.; Franco, O.H.; Schoufour, J.D. Adherence to the 2015 Dutch dietary guidelines and risk of non-communicable diseases and mortality in the Rotterdam study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 32, 993–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrie, G.A.; Golley, R.K.; Noakes, M. Compliance with dietary guidelines varies by weight status: A cross-sectional study of Australian adults. Nutrients 2018, 10, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessri, M.; L’Abbe, M.R. The time for an updated Canadian food guide has arrived. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 40, 854–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessri, M.; Nishi, S.K.; L’Abbé, M.R. Assessing the nutritional quality of diets of canadian adults using the 2014 health Canada surveillance tool tier system. Nutrients 2015, 7, 10447–10468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Canada. Canada’s Food Guide Consultation—Phase 1 What We Heard Report. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/food-nutrition/canada-food-guide-phase1-what-we-heard.html (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Health Canada. Canada’s Food Guide Consultation—Phase 2 What We Heard Report. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/health/publications/food-nutrition/canada-food-guide-phase2-what-we-heard.html (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Health Canada. 2019 Canada’s Food Guide. Available online: https://food-guide.canada.ca/en/ (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- Swinburn, B.; Vandevijvere, S.; Kraak, V.; Sacks, G.; Snowdon, W.; Hawkes, C.; Barquera, S.; Friel, S.; Kelly, B.; Kumanyika, S.; et al. Monitoring and benchmarking government policies and actions to improve the healthiness of food environments: A proposed government healthy food environment policy index. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14 (Suppl. 1), 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swinburn, B.; Sacks, G.; Vandevijvere, S.; Kumanyika, S.; Lobstein, T.; Neal, B.; Barquera, S.; Friel, S.; Hawkes, C.; Kelly, B.; et al. Informas (international network for food and obesity/non-communicable diseases research, monitoring and action support): Overview and key principles. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14 (Suppl. 1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swinburn, B.; Sacks, G.; Ravussin, E. Increased food energy supply is more than sufficient to explain the US epidemic of obesity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 1453–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Moubarac, J.C.; Cannon, G.; Ng, S.W.; Popkin, B. Ultra-processed products are becoming dominant in the global food system. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14 (Suppl. 2), 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moubarac, J.C.; Martins, A.P.; Claro, R.M.; Levy, R.B.; Cannon, G.; Monteiro, C.A. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and likely impact on human health. Evidence from Canada. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 2240–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, J.J.; Mudryj, A.N. Are we really “eating well with Canada’s food guide”? BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Arellano, B.; Bernstein, J.T.; Norsen, S.; Schermel, A.; L’Abbé, M.R. Assessing nutrition and other claims on food labels: A repeated cross-sectional analysis of the Canadian food supply. BMC Nutr. 2017, 3, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoforou, A.; Dachner, N.; Mendelson, R.; Tarasuk, V. Front-of-package nutrition references are positively associated with food processing. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulker, C.E.; Scott, J.A.; Pollard, C.M. Ultra-processed family foods in australia: Nutrition claims, health claims and marketing techniques. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hieke, S.; Kuljanic, N.; Pravst, I.; Miklavec, K.; Kaur, A.; Brown, K.A.; Egan, B.M.; Pfeifer, K.; Gracia, A.; Rayner, M. Prevalence of nutrition and health-related claims on pre-packaged foods: A five-country study in Europe. Nutrients 2016, 8, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pravst, I.; Kušar, A. Consumers’ exposure to nutrition and health claims on pre-packed foods: Use of sales weighting for assessing the food supply in Slovenia. Nutrients 2015, 7, 9353–9368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, A.; Scarborough, P.; Rayner, M. A systematic review, and meta-analyses, of the impact of health-related claims on dietary choices. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talati, Z.; Norman, R.; Kelly, B.; Dixon, H.; Neal, B.; Miller, C.; Pettigrew, S. A randomized trial assessing the effects of health claims on choice of foods in the presence of front-of-pack labels. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 108, 1275–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, S.K.; Jessri, M.; L’Abbé, M. Assessing the dietary habits of Canadians by eating location and occasion: Findings from the Canadian community health survey, cycle 2.2. Nutrients 2018, 10, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eidner, M.B.; Lund, A.S.; Harboe, B.S.; Clemmensen, I.H. Calories and portion sizes in recipes throughout 100 years: An overlooked factor in the development of overweight and obesity? Scand J. Public Health 2013, 41, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poti, J.M.; Braga, B.; Qin, B. Ultra-processed food intake and obesity: What really matters for health-processing or nutrient content? Curr. Obes. Rep. 2017, 6, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kleef, E.; Dagevos, H. The growing role of front-of-pack nutrition profile labeling: A consumer perspective on key issues and controversies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 55, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Flaherty, M.; Bandosz, P.; Critchley, J.; Capewell, S.; Guzman-Castillo, M.; Aspelund, T.; Bennett, K.; Kabir, K.; Björck, L.; Bruthans, J.; et al. Exploring potential mortality reductions in 9 European countries by improving diet and lifestyle: A modelling approach. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 207, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarborough, P.; Matthews, A.; Eyles, H.; Kaur, A.; Hodgkins, C.; Raats, M.M.; Rayner, M. Reds are more important than greens: How UK supermarket shoppers use the different information on a traffic light nutrition label in a choice experiment. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson-Stuttard, J.; Kypridemos, C.; Collins, B.; Mozaffarian, D.; Huang, Y.; Bandosz, P.; Capewell, S.; Whitsel, L.; Wilde, P.; O’Flaherty, M.; et al. Estimating the health and economic effects of the proposed us food and drug administration voluntary sodium reformulation: Microsimulation cost-effectiveness analysis. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emrich, T.E.; Qi, Y.; Lou, W.Y.; L’Abbe, M.R. Traffic-light labels could reduce population intakes of calories, total fat, saturated fat, and sodium. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peñalvo, J.L.; Cudhea, F.; Micha, R.; Rehm, C.D.; Afshin, A.; Whitsel, L.; Wilde, P.; Gaziano, T.; Pearson-Stuttard, J.; O’Flaherty, M.; et al. The potential impact of food taxes and subsidies on cardiovascular disease and diabetes burden and disparities in the United States. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobiac, L.J.; Scarborough, P. Translating the who 25×25 goals into a UK context: The promise modelling study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e012805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosettie, K.L.; Micha, R.; Cudhea, F.; Peñalvo, J.L.; O’Flaherty, M.; Pearson-Stuttard, J.; Economos, C.D.; Whitsel, L.P.; Mozaffarian, D. Comparative risk assessment of school food environment policies and childhood diets, childhood obesity, and future cardiometabolic mortality in the United States. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CODEX Alimentarius. Guidelines on Nutrition Labelling (cac/gl 2-1985); Joint FAO/WHO Codex Alimentarius Commission: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rayner, M.; Wood, A.; Lawrence, M.; Mhurchu, C.N.; Albert, J.; Barquera, S.; Friel, S.; Hawkes, C.; Kelly, B.; Kumanyika, S.; et al. Monitoring the health-related labelling of foods and non-alcoholic beverages in retail settings. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14 (Suppl. 1), 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Te Morenga, L.A.; Howatson, A.J.; Jones, R.M.; Mann, J. Dietary sugars and cardiometabolic risk: Systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of the effects on blood pressure and lipids. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Katan, M.B.; Ascherio, A.; Stampfer, M.J.; Willett, W.C. Trans fatty acids and cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 1601–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessri, M.; Wolfinger, R.D.; Lou, W.Y.; L’Abbé, M.R. Identification of dietary patterns associated with obesity in a nationally representative survey of canadian adults: Application of a priori, hybrid, and simplified dietary pattern techniques. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 105, 669–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, M.; Vandevijvere, S. Informas Protocol: Food Labelling Module. Available online: https://figshare.com/articles/INFORMAS_Protocol_Food_Labelling_Module/5673643 (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Bernstein, J.T.; Schermel, A.; Mills, C.M.; L’Abbe, M.R. Total and free sugar content of canadian prepackaged foods and beverages. Nutrients 2016, 8, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Scarborough, P.; Hieke, S.; Kusar, A.; Pravst, I.; Raats, M.; Rayner, M. The nutritional quality of foods carrying health-related claims in Germany, The Netherlands, Spain, Slovenia and the United Kingdom. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 1388–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ani, H.H.; Devi, A.; Eyles, H.; Swinburn, B.; Vandevijvere, S. Nutrition and health claims on healthy and less-healthy packaged food products in New Zealand. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 116, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, A.; Scarborough, P.; Matthews, A.; Payne, S.; Mizdrak, A.; Rayner, M. How many foods in the UK carry health and nutrition claims, and are they healthier than those that do not? Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 988–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pongutta, S.; Chongwatpol, P.; Tantayapirak, P.; Vandevijvere, S. Declaration of nutrition information on and nutritional quality of Thai ready-to-eat packaged food products. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 1409–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunford, E.; Webster, J.; Metzler, A.B.; Czernichow, S.; Ni Mhurchu, C.; Wolmarans, P.; Snowdon, W.; L’Abbe, M.; Li, N.; Maulik, P.K.; et al. International collaborative project to compare and monitor the nutritional composition of processed foods. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2012, 19, 1326–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Canada. The Development and Use of a Surveillance Tool: The Classification of Foods in the Canadian Nutrient File According to Eating Well with Canada’s Food Guide. Available online: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2014/sc-hc/H164-158-2-2014-eng.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2018).

- Poon, T.; Labonté, M.; Mulligan, C.; Ahmed, M.; Dickinson, K.M.; L’Abbé, M.R. Comparison of nutrient profiling models for assessing the nutritional quality of foods: A validation study. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 120, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackay, S.; Vandevijvere, S.; Xie, P.; Lee, A.; Swinburn, B. Paying for convenience: Comparing the cost of takeaway meals with their healthier home-cooked counterparts in New Zealand. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 2269–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, S.; Hammond, D.; Pillo-Blocka, F.; Glanville, T.; Jenkins, R. Use of nutritional information in canada: National trends between 2004 and 2008. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2011, 43, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderlee, L.; Goodman, S.; Sae Yang, W.; Hammond, D. Consumer understanding of calorie amounts and serving size: Implications for nutritional labelling. Can. J. Public Health 2012, 103, e327–e331. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, C.L.; Mendoza, J.; Henson, S.J.; Qi, Y.; Lou, W.; L’Abbé, M.R. Consumer attitudes and understanding of cholesterol-lowering claims on food: Randomize mock-package experiments with plant sterol and oat fibre claims. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 68, 946–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corby, L. Eating well. CMAJ 2007, 177, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondro, W. Proposed canada food guide called “obesogenic”. CMAJ 2006, 174, 605–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco-Arellano, B.; Labonté, M.; Bernstein, J.T.; L’Abbé, M.R. Examining the nutritional quality of canadian packaged foods and beverages with and without nutrition claims. Nutrients 2018, 10, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, J.T.; Franco-Arellano, B.; Schermel, A.; Labonté, M.; L’Abbé, M.R. Healthfulness and nutritional composition of canadian prepackaged foods with and without sugar claims. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 42, 1217–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada. Regulations Amending Certain Regulations Made under the Food and Drugs Act (Nutrition Symbols, Other Labelling Provisions, Partially Hydrogenated Oils and Vitamin D). Available online: http://www.gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p1/2018/2018-02-10/pdf/g1-15206.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2018).

- Machín, L.; Cabrera, M.; Curutchet, M.R.; Martínez, J.; Giménez, A.; Ares, G. Consumer perception of the healthfulness of ultra-processed products featuring different front-of-pack nutrition labeling schemes. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49, 330.e1–338.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talati, Z.; Pettigrew, S.; Neal, B.; Dixon, H.; Hughes, C.; Kelly, B.; Miller, C. Consumers’ responses to health claims in the context of other on-pack nutrition information: A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberto, C.A.; Khandpur, N. Improving the design of nutrition labels to promote healthier food choices and reasonable portion sizes. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 2014, 38 (Suppl. 1), S25–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrúa, A.; Machín, L.; Curutchet, M.R.; Martínez, J.; Antúnez, L.; Alcaire, F.; Giménez, A.; Ares, G. Warnings as a directive front-of-pack nutrition labelling scheme: Comparison with the guideline daily amount and traffic-light systems. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 2308–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, G.; Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Curutchet, M.R.; Antúnez, L.; Machín, L.; Vidal, L.; Giménez, A. Product reformulation in the context of nutritional warning labels: Exploration of consumer preferences towards food concepts in three food categories. Food Res. Int. 2018, 107, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Regulation (ec) No 1924/2006 on Nutrition and Health Claims Made on Foods. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A02006R1924-20121129 (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code. Standard 1.2.7—Nutrition, Health and Related Claims. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2017C01048 (accessed on 11 May 2018).

- Nieto, C.; Rincon-Gallardo Patiño, S.; Tolentino-Mayo, L.; Carriedo, A.; Barquera, S. Characterization of breakfast cereals available in the mexican market: Sodium and sugar content. Nutrients 2017, 9, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Kingdom—Food Standards Agency and Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs. Food Labelling: Giving Food Information to Consumers. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/food-labelling-giving-food-information-to-consumers-give-a-quantitative-ingredients-declaration-quid (accessed on 19 December 2018).

- European Commision. Commission Notice on the Application of the Principle of Quantitative Ingredients Declaration (Quid). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52017XC1121(01) (accessed on 19 December 2018).

- Food Standards Australia New Zealand. Ingredient Lists and Percentage Labelling. Available online: http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/consumer/labelling/ingredients/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 19 December 2018).

- Emrich, T.E.; Qi, Y.; Cohen, J.E.; Lou, W.Y.; L’Abbe, M.L. Front-of-pack symbols are not a reliable indicator of products with healthier nutrient profiles. Appetite 2015, 84, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emrich, T.E.; Cohen, J.E.; Lou, W.Y.; L’Abbé, M.R. Food products qualifying for and carrying front-of-pack symbols: A cross-sectional study examining a manufacturer led and a non-profit organization led program. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Tier | Alignment to CFG | Conditions: Fats, Sugars and Sodium Content of Foods | Thresholds | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Foods in line with CFG | Foods that do not exceed any of the three lower thresholds for total fat, sugars and sodium 2 | Lower thresholds: Total Fat: ≤3 g/RA | |

| 2 | Foods in line with CFG | Foods that exceed one or two lower thresholds for total fat, sugars or sodium, without exceeding any upper thresholds | Sugars: ≤6 g/RA Sodium: ≤140 mg/RA | |

| 3 | Foods partially in line with CFG | Vegetables and Fruit and Grain Products | Milk and Alternatives and Meat and Alternatives | |

| Foods that exceed all three lower thresholds without exceeding any upper thresholds for total fat, saturated fat, sugars or sodium, or | Foods that exceed all three lower thresholds without exceeding any upper thresholds for total fat, sugars or sodium 3, or | |||

| Foods that exceed only one upper threshold for total fat, saturated fat, sugars or sodium | Foods that exceed only one upper threshold for total fat, sugars or sodium 3, or | |||

| Foods that only exceed the upper saturated fat threshold | ||||

| 4 | Foods not in line with CFG | Vegetables and Fruit and Grain Products | Milk and Alternatives and Meat and Alternatives | Upper thresholds: Total Fat: >10 g/RA, Sugars: >19 g/RA, Sodium: >360 mg/RA, |

| Foods that exceed at least two upper thresholds for total fat, saturated fat, sugars or sodium | Foods that exceed at least two upper thresholds for total fat, sugars or sodium 3 | Saturated fat: >2 g/RA | ||

| “Others” | Foods in line with CFG | Water, unsaturated fats and oils 4 | ||

| Foods not in line with CFG | High calorie beverages (≥40 kcal/100g), low calorie beverages (<40 kcal/100 g), high fat and/or sugar foods, meal replacements, saturated and/or trans fats and oils, supplements, ingredients/seasonings | |||

| Bakery (n = 2083) | Beverages (n = 1124) | Cereals (n = 1218) | Ice Creams & Desserts (n = 820) | Confectionary (n = 437) | Sugar & Honey (n = 193) | Snacks (n = 558) | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Label Components | ||||||||||||||

| List of ingredients | 2083 | 100% | 1124 | 100% | 1218 | 100% | 820 | 100% | 437 | 100% | 193 | 100% | 558 | 100% |

| Foods with QUID | 27 | 1.3% | 54 | 4.8% | 71 | 5.8% | 12 | 1.5% | 33 | 8% | 10 | 5.2% | 18 | 3.2% |

| Nutrient declarations (NFt) | 2083 | 100% | 1124 | 100% | 1218 | 100% | 820 | 100% | 437 | 100% | 193 | 100% | 558 | 100% |

| Supplementary Nutrition Information | 50 | 2.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 41 | 3.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 15 | 3% | 0 | 0.0% | 6 | 1.1% |

| Any nutrition or health claim 3 | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 1153 | 55.4% | 790 | 70.3% | 675 | 55.4% | 426 | 52.0% | 150 | 34% | 43 | 22.3% | 405 | 72.6% |

| Nutrition claims | 1146 | 55.0% | 790 | 70.3% | 672 | 55.2% | 426 | 52.0% | 146 | 33% | 43 | 22.3% | 405 | 72.6% |

| Nutrient content claims | 970 | 46.6% | 736 | 65.5% | 614 | 50.4% | 351 | 42.8% | 79 | 18% | 28 | 14.5% | 378 | 67.7% |

| Nutrient comparative claims | 41 | 2.0% | 37 | 3.3% | 11 | 0.9% | 58 | 7.1% | 3 | 1% | 15 | 7.8% | 51 | 9.1% |

| Health-related ingredient claims | 518 | 24.9% | 329 | 29.3% | 347 | 28.5% | 105 | 12.8% | 75 | 17% | 4 | 2.1% | 112 | 20.1% |

| Health claims | 215 | 10.3% | 112 | 10.0% | 155 | 12.7% | 28 | 3.4% | 5 | 1% | 1 | 0.5% | 21 | 3.8% |

| General health claims | 149 | 7.2% | 53 | 4.7% | 23 | 1.9% | 11 | 1.3% | 5 | 1% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 0.4% |

| Nutrient or other function claims | 17 | 0.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 10 | 0.8% | 15 | 1.8% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 0.5% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Reduction of disease risk claims 4 | 57 | 2.7% | 72 | 6.4% | 127 | 10.4% | 2 | 0.2% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0.0% | 19 | 3.4% |

| No | 930 | 44.6% | 334 | 29.7% | 543 | 44.6% | 394 | 48.0% | 287 | 66% | 150 | 77.7% | 153 | 27.4% |

| HCST Tier Classification 5 | ||||||||||||||

| Tier 1 - In line w/CFG | 216 | 10.4% | 40 | 3.6% | 454 | 37.3% | 33 | 4.0% | 7 | 1.3% | ||||

| Tier 2 - In line w/CFG | 1103 | 53.0% | 548 | 48.8% | 583 | 47.9% | 213 | 26.0% | 113 | 20.3% | ||||

| Tier 3 - Partially in line w/CFG | 520 | 25.0% | 54 | 4.8% | 73 | 6.0% | 445 | 54.3% | 308 | 55.2% | ||||

| Tier 4 - Not in line w/CFG | 244 | 11.7% | 18 | 1.5% | 129 | 15.7% | 130 | 23.3% | ||||||

| Others | 482 | 42.9% | 90 | 7.4% | 437 | 100% | 193 | 100% | - | - | ||||

| Processed fish (n = 440) | Meat and Meat Alt. (n = 908) | Sauces & spreads (n = 50) | FVNL (n = 1489) | Eggs (n = 56) | Total Products (n = 9376) | |||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Label Components | ||||||||||||||

| List of ingredients | 440 | 100% | 908 | 100% | 50 | 100% | 1489 | 100% | 56 | 100% | 9376 | 100% | ||

| Foods with QUID | 4 | 0.9% | 1 | 0.1% | 2 | 4.0% | 9 | 0.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 241 | 2.6% | ||

| Nutrient declarations (NFt) | 440 | 100% | 908 | 100% | 50 | 100% | 1489 | 100% | 56 | 100% | 9376 | 100% | ||

| Supplementary Nutrition Information | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 114 | 1.2% | ||

| Any nutrition or health claim 3 | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 217 | 49.3% | 339 | 37.3% | 12 | 24.0% | 657 | 44.1% | 30 | 53.6% | 4897 | 52.2% | ||

| Nutrition claims | 217 | 49.3% | 339 | 37.3% | 12 | 24.0% | 654 | 43.9% | 27 | 48.2% | 4875 | 52.0% | ||

| Nutrient content claims | 208 | 47.3% | 291 | 32.0% | 5 | 10.0% | 582 | 39.1% | 27 | 48.2% | 4269 | 45.5% | ||

| Nutrient comparative claims | 1 | 0.2% | 66 | 7.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 52 | 3.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 335 | 3.6% | ||

| Health-related ingredient claims | 8 | 1.8% | 7 | 0.8% | 7 | 14.0% | 113 | 7.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 1625 | 17.3% | ||

| Health claims | 21 | 4.8% | 12 | 1.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 93 | 6.2% | 23 | 41.1% | 686 | 7.3% | ||

| General health claims | 1 | 0.2% | 2 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 8 | 0.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 254 | 2.7% | ||

| Nutrient or other function claims | 16 | 3.6% | 5 | 0.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 8 | 0.5% | 2 | 3.6% | 74 | 0.8% | ||

| Reduction of disease risk claims 4 | 5 | 1.1% | 5 | 0.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 77 | 5.2% | 22 | 39.3% | 386 | 4.1% | ||

| No | 223 | 50.7% | 569 | 62.7% | 38 | 76.0% | 832 | 55.9% | 26 | 46.4% | 4479 | 47.8% | ||

| HCST Tier Classification 5 | ||||||||||||||

| Tier 1 - In line w/CFG | 50 | 11.4% | 2 | 0.2% | 143 | 9.6% | 945 | 10.1% | ||||||

| Tier 2 - In line w/CFG | 174 | 39.5% | 133 | 14.6% | 405 | 27.2% | 11 | 19.6% | 3283 | 35.0% | ||||

| Tier 3 - Partially in line w/CFG | 141 | 32.0% | 453 | 49.9% | 524 | 35.2% | 45 | 80.4% | 2563 | 27.3% | ||||

| Tier 4 - Not in line w/CFG | 75 | 17.0% | 320 | 35.2% | 56 | 3.8% | 972 | 10.4% | ||||||

| Others | 50 | 100% | 361 | 24.2% | 1613 | 17.2% | ||||||||

| Total | In Line with CFG | Unadjusted Model | Adjusted Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | % | β-Coefficients | SE | β-Coefficients | SE | |||

| Any nutrition or health claim | |||||||||

| Absent+ | 4479 | 1338 | 29.9% | ||||||

| Present | 4897 | 2893 | 59.1% | 1.22 | 0.044 | *** | 1.36 | 0.052 | *** |

| Nutrition claims | |||||||||

| Absent+ | 4501 | 1351 | 30.0% | ||||||

| Present | 4875 | 2880 | 59.1% | 1.21 | 0.044 | *** | 1.35 | 0.052 | *** |

| Nutrient content claims | |||||||||

| Absent+ | 5107 | 1551 | 30.4% | ||||||

| Present | 4269 | 2680 | 62.8% | 1.35 | 0.044 | *** | 1.50 | 0.053 | *** |

| Nutrient comparative claims | |||||||||

| Absent+ | 9041 | 4087 | 45.2% | ||||||

| Present | 335 | 144 | 43.0% | −0.09 | 0.112 | ns | 0.52 | 0.127 | *** |

| Health-related ingredient claims | |||||||||

| Absent+ | 7751 | 3122 | 40.3% | ||||||

| Present | 1625 | 1109 | 68.2% | 1.16 | 0.058 | *** | 0.91 | 0.068 | *** |

| Health claims | |||||||||

| Absent+ | 8690 | 3678 | 42.3% | ||||||

| Present | 686 | 553 | 80.6% | 1.73 | 0.099 | *** | 1.51 | 0.111 | *** |

| General health claims | |||||||||

| Absent+ | 9122 | 4023 | 44.1% | ||||||

| Present | 254 | 208 | 81.9% | 1.75 | 0.164 | *** | 1.36 | 0.178 | *** |

| Nutrient or other function claims | |||||||||

| Absent+ | 9302 | 4179 | 44.9% | ||||||

| Present | 74 | 52 | 70.3% | 1.06 | 0.255 | *** | 1.13 | 0.281 | *** |

| Reduction of disease risk claims | |||||||||

| Absent+ | 8990 | 3912 | 43.5% | ||||||

| Present | 386 | 319 | 82.6% | 1.82 | 0.136 | *** | 1.69 | 0.157 | *** |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Franco-Arellano, B.; Kim, M.A.; Vandevijvere, S.; Bernstein, J.T.; Labonté, M.-È.; Mulligan, C.; L’Abbé, M.R. Assessment of Packaged Foods and Beverages Carrying Nutrition Marketing against Canada’s Food Guide Recommendations. Nutrients 2019, 11, 411. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11020411

Franco-Arellano B, Kim MA, Vandevijvere S, Bernstein JT, Labonté M-È, Mulligan C, L’Abbé MR. Assessment of Packaged Foods and Beverages Carrying Nutrition Marketing against Canada’s Food Guide Recommendations. Nutrients. 2019; 11(2):411. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11020411

Chicago/Turabian StyleFranco-Arellano, Beatriz, Min Ah Kim, Stefanie Vandevijvere, Jodi T. Bernstein, Marie-Ève Labonté, Christine Mulligan, and Mary R. L’Abbé. 2019. "Assessment of Packaged Foods and Beverages Carrying Nutrition Marketing against Canada’s Food Guide Recommendations" Nutrients 11, no. 2: 411. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11020411

APA StyleFranco-Arellano, B., Kim, M. A., Vandevijvere, S., Bernstein, J. T., Labonté, M.-È., Mulligan, C., & L’Abbé, M. R. (2019). Assessment of Packaged Foods and Beverages Carrying Nutrition Marketing against Canada’s Food Guide Recommendations. Nutrients, 11(2), 411. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11020411