Infant Feeding Attitudes and Practices of Spanish Low-Risk Expectant Women Using the IIFAS (Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale)

Abstract

1. Introduction

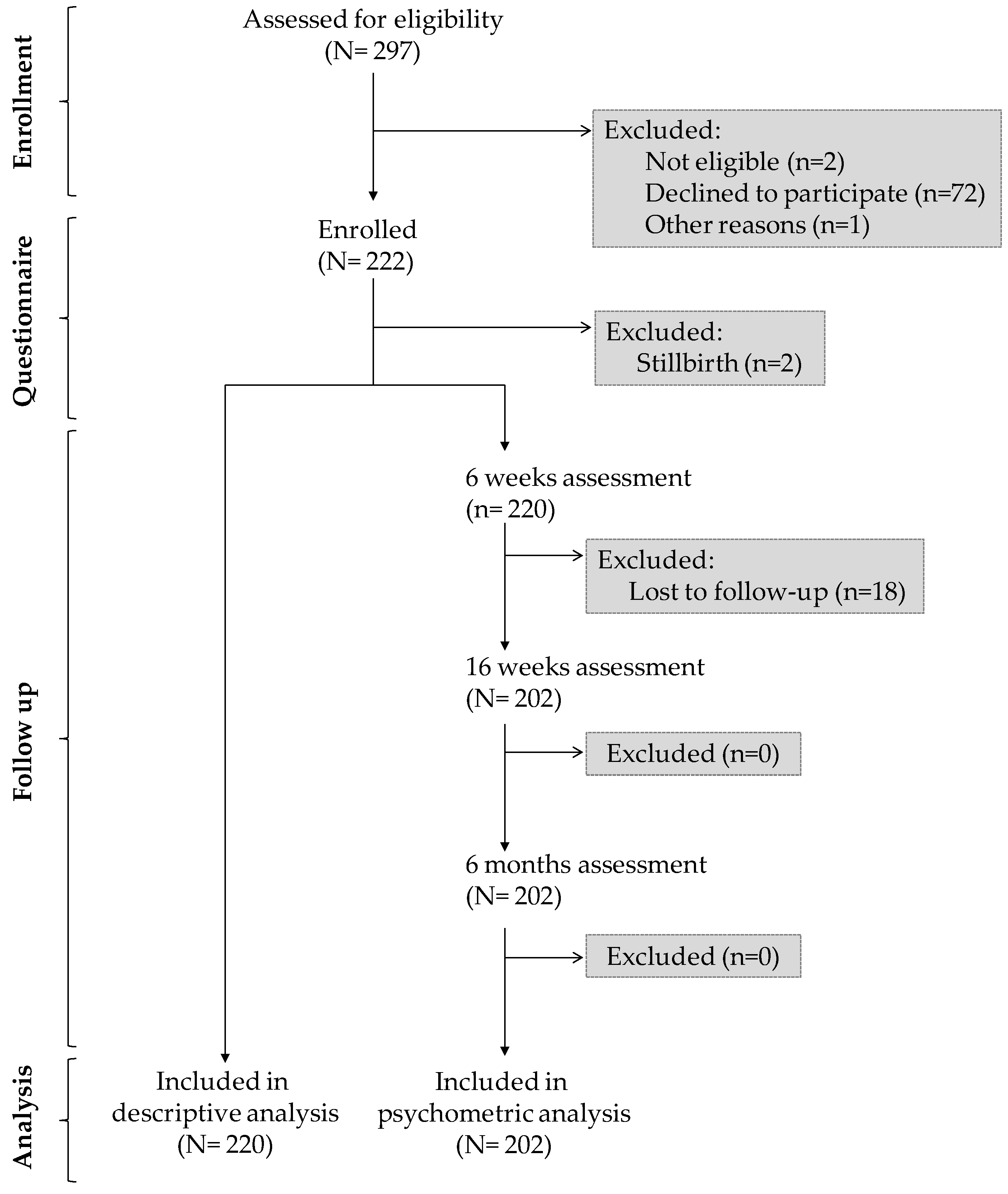

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects and Setting

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Development and Clinical Validation of the Spanish Version of the IIFAS (IIFAS-S)

2.3.1. Development of the Spanish Version of the IIFAS (IIFAS-S)

2.3.2. Clinical Validation of the Spanish Version of the IIFAS (IIFAS-S)

2.4. Statistical Methods

2.4.1. Descriptive Analysis

2.4.2. Attitudes towards Breastfeeding

2.4.3. Psychometric Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

3.2. Attitudes towards Breastfeeding

3.3. Infant-Feeding Attitudes and Demographic Factors

3.4. Validity

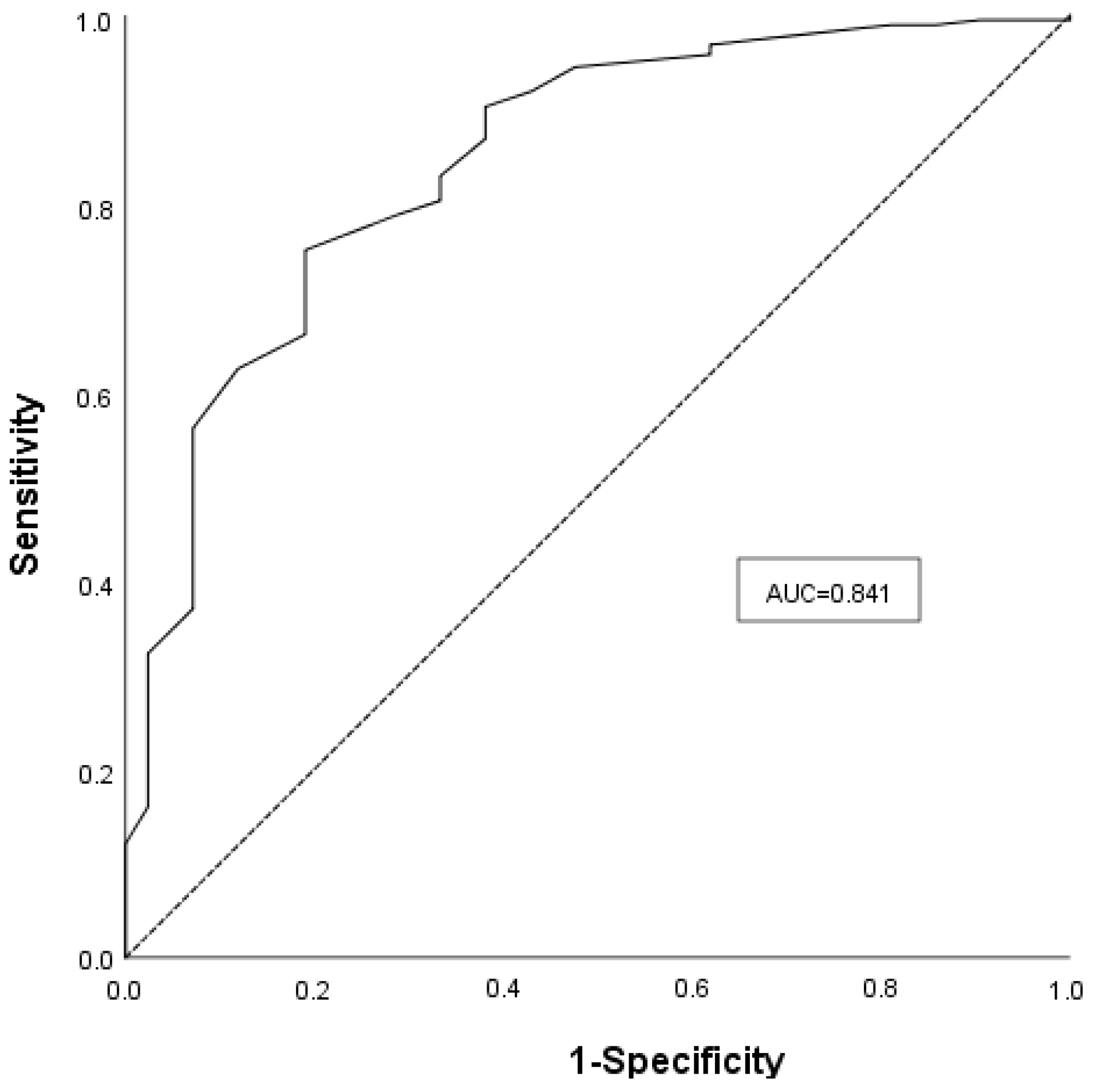

3.4.1. Predictive Validity

Prediction of breastfeeding intention

Prediction of breastfeeding duration

3.4.2. Internal Consistency Reliability

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Spanish Version | English Version |

|---|---|

| 1. Los beneficios nutricionales de la leche materna únicamente se mantienen hasta que el bebé es destetado. | 1. The nutritional benefits of breast milk last only until the baby is weaned from breast milk. |

| 2. La lactancia artificial es más conveniente que la lactancia materna. | 2. Formula feeding is more convenient than breast-feeding. |

| 3. El amamantamiento aumenta el vínculo afectivo entre madre e hijo. | 3. Breast-feeding increases mother–infant bonding. |

| 4. La leche materna carece de hierro. | 4. Breast milk is lacking in iron. |

| 5. Los bebés que se alimentan con leche artificial son más propensos a estar sobrealimentados que los alimentados con leche materna. | 5. Formula fed babies are more likely to be overfed than breast-fed babies. |

| 6. La lactancia artificial es la mejor elección si la madre planea trabajar fuera de casa. | 6. Formula feeding is the better choice if a mother plans to work outside the home. |

| 7. Las madres que alimentan a sus bebés con leche artificial se pierden uno de los grandes placeres de la maternidad. | 7. Mothers who formula feed miss one of the great joys of motherhood. |

| 8. Las madres no deberían amamantar en sitios públicos, como restaurantes. | 8. Women should not breast-feed in public places such as restaurants. |

| 9. Los bebés que se alimentan con leche materna son más sanos que los bebés que se alimentan con leche artificial. | 9. Babies fed breast milk are healthier than babies who are fed formula. |

| 10. Los bebés alimentados con leche materna son más propensos a estar sobrealimentados que los alimentados con leche artificial. | 10. Breast-fed babies are more likely to be overfed than formula fed babies. |

| 11. Los padres se sienten excluidos si la madre amamanta. | 11. Fathers feel left out if a mother breast-feeds. |

| 12. La leche materna es la alimentación ideal para los bebés. | 12. Breast milk is the ideal food for babies. |

| 13. La leche materna se digiere más fácilmente que la leche artificial. | 13. Breast milk is more easily digested than formula. |

| 14. La leche artificial es tan saludable para el niño como la leche materna. | 14. Formula is as healthy for an infant as breast milk. |

| 15. La lactancia materna es más conveniente que la lactancia artificial. | 15. Breast-feeding is more convenient than formula feeding. |

| 16. La leche materna es más barata que la leche artificial. | 16. Breast milk is less expensive than formula. |

| 17. Una madre que bebe alcohol ocasionalmente no debería amamantar a su bebé. | 17. A mother who occasionally drinks alcohol should not breast-feed her baby. |

Appendix B

| IIFAS-S | |

|---|---|

| Mean | 69.34 |

| Median | 70.00 |

| SE | 7.82 |

| Skewness | -0.62 |

| Kurtosis | 0.33 |

| Range | 39 |

Appendix C

Appendix D

| Item Variable a | Cronbach’s Alpha If Item Is Deleted | Item-Total Correlations |

|---|---|---|

| 1 b | 0.774 | 0.403 |

| 2 b | 0.765 | 0.597 |

| 3 | 0.772 | 0.422 |

| 4 b | 0.787 | 0.428 |

| 5 | 0.761 | 0.517 |

| 6 b | 0.776 | 0.505 |

| 7 | 0.773 | 0.540 |

| 8 b | 0.789 | 0.477 |

| 9 | 0.756 | 0.511 |

| 10 b | 0.784 | 0.528 |

| 11 b | 0.787 | 0.527 |

| 12 | 0.770 | 0.452 |

| 13 | 0.764 | 0.507 |

| 14 b | 0.761 | 0.543 |

| 15 | 0.762 | 0.538 |

| 16 | 0.788 | 0.432 |

| 17 b | 0.796 | 0.533 |

References

- National Institute for Public Health and the Environment. Health effects of Breastfeeding: An Update. RIVM Report 2015-0043. Available online: http://www.rivm.nl/dsresource?objectid=rivmp:276940&type=org&disposition=inline&ns_nc=1 (accessed on 13 December 2017).

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. Available online: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2003/9241562218.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 5 December 2017).

- Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Informe anual del Sistema Nacional de Salud 2012. Available online: http://www.msssi.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/sisInfSanSNS/tablasEstadisticas/InfSNS2012.htm (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- Dungy, C.I.; Losch, M.; Russell, D. Maternal attitudes as predictors of infant feeding decisions. J. Assoc. Acad. Minor. Phys. 1994, 5, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.H.; Chi, C.S. Maternal intention and actual behavior in infant feeding at one month postpartum. Acta Paediatr. Taiwan 2003, 44, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la Mora, A.; Russell, D.W. The Iowa infant feeding attitude scale: Analysis of reliability and validity. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 29, 2362–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Akour, N.A.; Khassawneh, M.Y.; Khader, Y.S.; Ababneh, A.A.; Haddad, A.M. Factors affecting intention to breastfeed among Syrian and Jordanian mothers: A comparative cross-sectional study. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2010, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charafeddine, L.; Tamim, H.; Soubra, M.; De la Mora, A.; Nabulsi, M.; Research and Advocacy Breastfeeding Team. Validation of the Arabic version of the Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale among Lebanese women. J. Hum. Lact. 2016, 32, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dungy, C.I.; Losch, M.E.; Russell, D.; Romitti, P.; Dusdieker, L.B. Hospital infant formula discharge packages. Do they affect the duration of breast-feeding? Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 1997, 151, 724–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dungy, C.I.; McInnes, R.J.; Tappin, D.M.; Wallis, A.B.; Oprescu, F. Infant feeding attitudes and knowledge among socioeconomically disadvantaged women in Glasgow. Matern. Child Health J. 2008, 12, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giglia, R.C.; Binns, C.W.; Alfonso, H.S.; Zhao, Y. Which mothers smoke before, during and after pregnancy? Public Health 2007, 121, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, Y.J.; McGrath, J.M. A Chinese version of Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale: Reliability and validity assessment. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011, 48, 475–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavanagh, K.F.; Lou, Z.; Nicklas, J.C.; Habibi, M.F.; Murphy, L.T. Breastfeeding knowledge, attitudes, prior exposure, and intent among undergraduate students. J. Hum. Lact. 2012, 28, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, Y.; Htun, T.P.; Lim, P.I.; Ho-Lim, S.S.; Klainin-Yobas, P. Psychometric properties of the Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale among a multiethnic population during pregnancy. J. Hum. Lact. 2016, 32, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahoney, M.C.; James, D.M. Predictors of anticipated breastfeeding in an urban, low-income setting. J. Fam. Pract. 2000, 49, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marrone, S.; Vogeltanz-Holm, N.; Holm, J. Attitudes, knowledge, and intentions related to breastfeeding among university undergraduate women and men. J. Hum. Lact. 2008, 24, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulcahy, H.; Phelan, A.; Corcoran, P.; Leahy-Warren, P. Examining the breastfeeding support resources of the public health nursing services in Ireland. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012, 21, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanishi, K.; Jimba, M. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale: A longitudinal study. J. Hum. Lact. 2014, 30, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, J.A.; Binns, C.W.; Oddy, W.H.; Graham, K.I. Predictors of breastfeeding duration: Evidence from a cohort study. Pediatrics 2006, 117, e646–e655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, J.A.; Shaker, I.; Reid, M. Parental attitudes toward breastfeeding: Their association with feeding outcome at hospital discharge. Birth 2004, 31, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaker, I.; Scott, J.A.; Reid, M. Infant feeding attitudes of expectant parents: Breastfeeding and formula feeding. J. Adv. Nurs. 2004, 45, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sittlington, J.; Stewart-Knox, B.; Wright, M.; Bradbury, I.; Scott, J.A. Infant-feeding attitudes of expectant mothers in Northern Ireland. Health Educ. Res. 2007, 22, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tappin, D.; Britten, J.; Broadfoot, M.; McInnes, R. The effect of health visitors on breastfeeding in Glasgow. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2006, 1, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomas-Almarcha, R.; Oliver-Roig, A.; Richart-Martinez, M. Reliability and validity of the reduced Spanish version of the Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2016, 45, e26–e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuthill, E.L.; Butler, L.M.; McGrath, J.M.; Cusson, R.M.; Makiwane, G.N.; Gable, R.K.; Fisher, J.D. Cross-cultural adaptation of instruments assessing breastfeeding determinants: A multi-step approach. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2014, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twells, L.K.; Midodzi, W.K.; Ludlow, V.; Murphy-Goodridge, J.; Burrage, L.; Gill, N.; Halfyard, B.; Schiff, R.; Newhook, L.A. Assessing infant feeding attitudes of expectant women in a provincial population in Canada: Validation of the Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale. J. Hum. Lact. 2016, 32, NP9–NP18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallis, A.B.; Brînzaniuc, A.; Cherecheş, R.; Oprescu, F.; Sirlincan, E.; David, I.; Dîrle, I.A.; Dungy, C.I. Reliability and validity of the Romanian version of a scale to measure infant feeding attitudes and knowledge. Acta Paediatr. 2008, 97, 1194–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkins, C.; Ryan, K.; Green, J.; Thomas, P. Infant feeding attitudes of women in the United Kingdom during pregnancy and after birth. J. Hum. Lact. 2012, 28, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, J.A.; McInnes, R.J.; Hoddinott, P.; Alder, E.M. A systematic review of measures assessing mothers’ knowledge, attitudes, confidence and satisfaction towards breastfeeding. Breastfeed. Rev. 2007, 15, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality. Clinical Practice Guideline for Care in Pregnancy and Puerperium. Available online: http://www.guiasalud.es/GPC/GPC_533_Embarazo_AETSA_compl_en.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2018).

- Kozhimannil, K.B.; Jou, J.; Attanasio, L.B.; Joarnt, L.K.; McGovern, P. Medically complex pregnancies and early breastfeeding behaviors: A retrospective analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Recommendations for the Cross-Cultural Adaptation of the DASH & QuickDASH Outcome Measures; American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and Institute for Work & Health: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2007; Volume 1, pp. 1–45. Available online: http://www.dash.iwh.on.ca/sites/dash/files/downloads/cross_cultural_adaptation_2007.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2018).

- Sperber, A.D.; Devellis, R.F.; Boehlecke, B. Cross-cultural translation: Methodology and validation. J. Cross. Cult. Psychol. 1994, 25, 501–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1412980449. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J. My current thoughts on coefficient alpha and successor procedures. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2004, 64, 391–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, J.P.; Brunner, M.; Loarer, E.; Houssemand, C. Incomplete psychometric equivalence of scores obtained on the manual and the computer version of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test? Psychol. Assess. 2010, 22, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaju, A.; Crask, M.R. The perfect design: Optimization between reliability, validity, redundancy in scale items and response rates. Am. Market. Assoc. 1999, 10, 127–131. [Google Scholar]

- Streiner, D.L. Figuring out factors: The use and misuse of factor analysis. Can. J. Psychiatry 1994, 39, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, J.A.; Kwok, Y.Y.; Synnott, K.; Bogue, J.; Amarri, S.; Norin, E.; Gil, A.; Edwards, C.A.; Other Members of the INFABIO Project Team. A comparison of maternal attitudes to breastfeeding in public and the association with breastfeeding duration in four European countries: Results of a cohort study. Birth 2015, 42, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Hsia, J.; Fridinger, F.; Hussain, A.; Benton-Davis, S.; Grummer-Strawn, L. Public beliefs about breastfeeding policies in various settings. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2004, 104, 1162–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs. Transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human milk. Pediatrics 2001, 108, 776–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boletín Oficial del Estado. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2015-11430 (accessed on 12 February 2018).

- Barona-Vilar, C.; Escribá-Agüir, V.; Ferrero-Gandía, R. A qualitative approach to social support and breast-feeding decisions. Midwifery 2009, 25, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Spanish (n = 122) | Galician (n = 98) | Total (n = 220) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Mother’s age | 18–34 | 73 | 59.8 | 63 | 64.3 | 136 | 61.8 |

| ≥35 | 48 | 39.3 | 35 | 35.7 | 83 | 37.7 | |

| No response | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | |

| Marital status | Married | 69 | 56.6 | 56 | 57.1 | 125 | 56.8 |

| Cohabiting | 45 | 36.9 | 39 | 39.8 | 84 | 38.2 | |

| Single | 7 | 5.7 | 2 | 2.0 | 9 | 4.1 | |

| No response | 1 | 0.8 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.9 | |

| Nationality | Spanish | 116 | 95.1 | 97 | 99 | 213 | 96.8 |

| Others | 6 a | 4.9 | 1 b | 1 | 7 | 3.2 | |

| No response | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Level of education | Secondary education or lower | 45 | 36.9 | 29 | 29.6 | 74 | 33.6 |

| Apprentice | 22 | 18 | 26 | 26.5 | 48 | 21.8 | |

| Graduate or above | 54 | 44.3 | 42 | 42.9 | 96 | 43.6 | |

| No response | 1 | 0.8 | 1 | 1.0 | 2 | 0.9 | |

| Parity | Primiparous | 100 | 82.0 | 71 | 72.4 | 171 | 77.7 |

| Multiparous | 22 | 18.0 | 27 | 27.6 | 49 | 22.3 | |

| No response | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Primary public health care centre | Ferrol | 49 | 40.2 | 32 | 32.7 | 81 | 36.8 |

| Narón | 48 | 39.3 | 38 | 38.8 | 86 | 39.1 | |

| Fene | 11 | 9.0 | 14 | 14.3 | 25 | 11.4 | |

| Ortigueira | 2 | 1.6 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1.4 | |

| As Pontes de García Rodríguez | 8 | 6.6 | 10 | 10.2 | 18 | 8.2 | |

| Valdoviño | 3 | 2.5 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2.3 | |

| San Sadurniño | 1 | 0.8 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.9 | |

| No response | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Occupation | Employee | 80 | 65.6 | 60 | 61.2 | 140 | 63.6 |

| Self-employed | 10 | 8.2 | 8 | 8.2 | 18 | 8.2 | |

| Student | 4 | 3.3 | 3 | 3.1 | 7 | 3.2 | |

| Housewife | 27 | 22.1 | 27 | 27.6 | 54 | 24.5 | |

| No response | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | |

| Previous breastfeeding experience c | Exclusive breastfeeding | 14 | 63.6 | 16 | 59.3 | 30 | 61.2 |

| Fully or partially formula feed | 8 | 36.4 | 9 | 33.3 | 17 | 34.7 | |

| No response | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7.4 | 2 | 4.1 | |

| Infant feeding intention | Exclusive breastfeeding | 106 | 86.9 | 92 | 93.9 | 198 | 90 |

| Fully or partially formula feed | 15 | 12.3 | 6 | 6.1 | 21 | 9.6 | |

| It had not been decided | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | |

| Item Variable a | M | SD | Agree (%) | Neutral (%) | Disagree (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The nutritional benefits of breast milk last only until the baby is weaned from breast milk b | 3.95 | 1.27 | 73.6 | 8.6 | 17.7 |

| 2. Formula feeding is more convenient than breast-feeding b | 4.64 | 0.75 | 93.2 | 4.1 | 2.7 |

| 3. Breast-feeding increases mother–infant bonding | 4.64 | 0.83 | 93.6 | 2.3 | 4.1 |

| 4. Breast milk is lacking in iron b | 4.26 | 0.98 | 82.7 | 10.9 | 6.4 |

| 5. Formula fed babies are more likely to be overfed than breast-fed babies | 3.32 | 1.16 | 46.8 | 28.2 | 25 |

| 6. Formula feeding is the better choice if a mother plans to work outside the home b | 3.81 | 0.96 | 65.5 | 25.9 | 8.6 |

| 7. Mothers who formula feed miss one of the great joys of motherhood | 3.80 | 1.11 | 61.4 | 28.2 | 10.5 |

| 8. Women should not breast-feed in public places such as restaurants b | 4.40 | 0.98 | 84.1 | 10.9 | 5.0 |

| 9. Babies fed breast milk are healthier than babies who are fed formula | 3.95 | 1.08 | 70.0 | 18.2 | 11.8 |

| 10. Breast-fed babies are more likely to be overfed than formula fed babies b | 3.98 | 1.05 | 72.7 | 19.1 | 8.2 |

| 11. Fathers feel left out if a mother breast-feeds b | 4.18 | 0.88 | 82.7 | 12.3 | 5 |

| 12. Breast milk is the ideal food for babies | 4.63 | 0.78 | 93.6 | 3.6 | 2.7 |

| 13. Breast milk is more easily digested than formula | 4.24 | 0.91 | 77.3 | 19.5 | 3.2 |

| 14. Formula is as healthy for an infant as breast milk b | 4.00 | 0.91 | 77.7 | 15.0 | 7.3 |

| 15. Breast-feeding is more convenient than formula feeding | 4.47 | 0.78 | 89.1 | 8.6 | 2.3 |

| 16. Breast milk is less expensive than formula | 4.75 | 0.63 | 95.9 | 2.3 | 1.8 |

| 17. A mother who occasionally drinks alcohol should not breast-feed her baby b | 2.74 | 1.26 | 33.2 | 19.1 | 47.7 |

| Total | 69.76 | 7.75 | 57.7 | 40.9 | 1.4 |

| Demographic Factor a | Mean Score (SD) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother’s age | 18–34 | 68.77 (7.93) | 0.112 |

| ≥35 | 71.35 (7.25) | ||

| Marital status | Married | 70.06 (8.11) | 0.101 |

| Cohabiting | 69.89 (6.35) | ||

| Single | 65.67 (12.55) | ||

| Level of education | Secondary education or lower | 69.46 (7.82) | 0.699 |

| Apprentice | 68.79 (8.32) | ||

| Graduate or above | 70.60 (7.32) | ||

| Parity | Primiparous | 68.80 (7.70) | 0.034 * |

| Multiparous | 73.10 (7.05) | ||

| Occupation | Employee | 69.76 (8.17) | 0.798 |

| Self-employed | 69.67 (7.73) | ||

| Student | 68.43 (4.35) | ||

| Housewife | 69.91 (7.15) | ||

| Exclusively Breastfeed | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||||

| Item Variable a,b | Agree (%) | Neutral (%) | Disagree (%) | Agree (%) | Neutral (%) | Disagree (%) | p Value |

| 1 c | 74.5 | 8.5 | 17 | 66.7 | 6.7 | 26.7 | 0.657 |

| 2 c | 95.3 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 73.3 | 26.7 | 0 | 0.000 |

| 3 | 95.3 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 73.3 | 13.3 | 13.3 | 0.009 |

| 4 c | 85.8 | 9.4 | 4.7 | 80.0 | 20.0 | 0.0 | 0.345 |

| 5 | 49.1 | 29.2 | 21.7 | 26.7 | 20.0 | 53.3 | 0.031 |

| 6 c | 65.1 | 27.4 | 7.5 | 33.3 | 46.7 | 20 | 0.048 |

| 7 | 69.8 | 25.5 | 4.7 | 33.3 | 20.0 | 46.7 | 0.000 |

| 8 c | 85.8 | 11.3 | 2.8 | 46.7 | 33.3 | 20.0 | 0.001 |

| 9 | 75.5 | 17 | 7.5 | 13.3 | 33.3 | 53.3 | 0.000 |

| 10 c | 68.9 | 20.8 | 10.4 | 86.7 | 13.3 | 0.0 | 0.285 |

| 11 c | 87.7 | 9.4 | 2.8 | 73.3 | 13.3 | 13.3 | 0.134 |

| 12 | 95.3 | 2.8 | 1.9 | 66.7 | 33.3 | 0.0 | 0.000 |

| 13 | 83.0 | 16.0 | 0.9 | 53.3 | 40.0 | 6.7 | 0.018 |

| 14 c | 82.1 | 14.2 | 3.8 | 46.7 | 20.0 | 33.3 | 0.000 |

| 15 | 89.6 | 8.5 | 1.9 | 66.7 | 20.0 | 13.3 | 0.021 |

| 16 | 93.4 | 4.7 | 1.9 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0.591 |

| 17 c | 27.4 | 21.7 | 50.9 | 20.0 | 6.7 | 73.3 | 0.224 |

| Total score | 59.4 | 40.6 | 0.0 | 13.3 | 73.3 | 13.3 | 0.000 |

| Exclusively Breastfeed a | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||||

| Duration | Agree (%) | Neutral (%) | Disagree (%) | Agree (%) | Neutral (%) | Disagree (%) | p Value | |

| IIFAS | 6 weeks | 38 (60.3) | 25 (39.7) | 0 (0.0) | 23 (46.0) | 25 (50.0) | 2 (4.0) | 0.019 |

| 16 weeks | 32 (64.0) | 18 (36.0) | 0 (0.0) | 29 (46.0) | 32 (50.8) | 2 (3.2) | 0.049 | |

| 6 months | 17 (68.0) | 8 (32.0) | 0 (0.0) | 44 (50.0) | 42 (47.7) | 2 (2.3) | 0.024 | |

| Exclusively Breastfeeding n (%) | Non-Exclusively Breastfeeding n (%) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 WEEKS | ||||

| Intention | Exclusively breastfeeding | 60 (60.6) | 39 (39.4) | 0.006 |

| Nonexclusively breastfeeding | 3 (21.4) | 11 (78.6) | ||

| 16 WEEKS | ||||

| Intention | Exclusively breastfeeding | 48 (48.5) | 51 (51.5) | 0.016 |

| Nonexclusively breastfeeding | 2 (14.3) | 12 (85.7) | ||

| 6 MONTHS | ||||

| Intention | Exclusively breastfeeding | 24 (24.2) | 75 (75.8) | 0.049 |

| Nonexclusively breastfeeding | 1 (7.1) | 13 (92.9) | ||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cotelo, M.D.C.S.; Movilla-Fernández, M.J.; Pita-García, P.; Novío, S. Infant Feeding Attitudes and Practices of Spanish Low-Risk Expectant Women Using the IIFAS (Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale). Nutrients 2018, 10, 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10040520

Cotelo MDCS, Movilla-Fernández MJ, Pita-García P, Novío S. Infant Feeding Attitudes and Practices of Spanish Low-Risk Expectant Women Using the IIFAS (Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale). Nutrients. 2018; 10(4):520. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10040520

Chicago/Turabian StyleCotelo, María Del Carmen Suárez, María Jesús Movilla-Fernández, Paula Pita-García, and Silvia Novío. 2018. "Infant Feeding Attitudes and Practices of Spanish Low-Risk Expectant Women Using the IIFAS (Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale)" Nutrients 10, no. 4: 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10040520

APA StyleCotelo, M. D. C. S., Movilla-Fernández, M. J., Pita-García, P., & Novío, S. (2018). Infant Feeding Attitudes and Practices of Spanish Low-Risk Expectant Women Using the IIFAS (Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale). Nutrients, 10(4), 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10040520