MAF-RecNet: A Lightweight Wheat and Corn Recognition Model Integrating Multiple Attention Mechanisms

Highlights

- MAF-RecNet achieves an excellent balance between accuracy and efficiency. For southern Hebei farmland recognition, it attains 87.57% mIoU and 95.42% mAP, outperforming models like SegNeXt and FastSAM, while remaining lightweight (15.25 M parameters, 21.81 GFLOPs).

- The model also shows strong generalization, reaching 90.20% mIoU on a global wheat disease dataset, and maintains robust performance under noise and degradation tests, confirming its reliability in diverse real-world scenarios.

- This study provides a practical solution for intelligent agricultural identification. By tackling key challenges like high model complexity, small-sample overfitting, and limited cross-domain generalization, MAF-RecNet achieves high accuracy with a lightweight design, offering a deployable tool for tasks such as crop census and disease monitoring.

- Furthermore, it offers methodological insights for designing lightweight models. Its validated modular components—including a hybrid attention mechanism, a pre-trained backbone, and dual-attention skip connections—not only boost performance but also provide a transferable framework for addressing similar lightweight, small-sample recognition problems in other fields.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Construct a lightweight network architecture that integrates multi-attention mechanisms to reduce model complexity while enhancing the ability to discern multi-scale features and small targets in wheat and maize images.

- (2)

- Develop model optimization methods tailored for small-sample conditions, by incorporating pre-trained knowledge, designing efficient feature fusion modules, and employing hybrid loss functions, to mitigate overfitting with limited data and balance recognition accuracy with computational efficiency.

- (3)

- Establish a hierarchical, multi-task performance evaluation framework to systematically validate the model’s performance across crop recognition tasks of varying regions and scales, and to test its cross-domain generalization capability and robustness under noisy conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Acquisition and Preprocessing of Remote Sensing Images

2.2. Dataset Construction

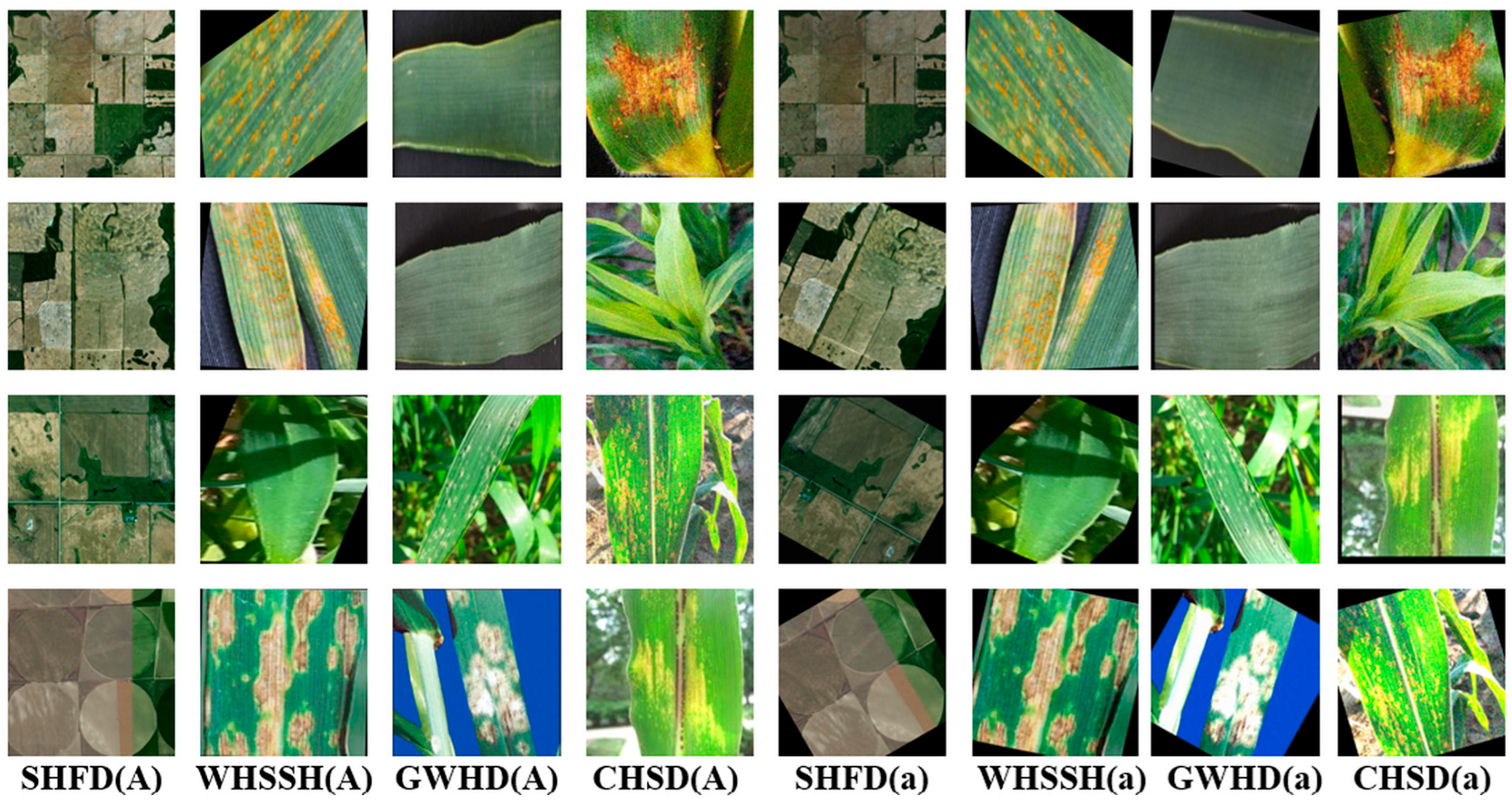

2.2.1. Pre-Enhanced Image Dataset

- (1)

- Complementarity in Modality and Scale: SHFD (macro-scale satellite imagery) and the other three datasets (micro-scale close-range imagery) together form a complete span of “spatial scales,” covering core agricultural vision tasks ranging from field-level distribution identification to organ-level pathological diagnosis.

- (2)

- Representativeness of Data Sources: The combination includes both internationally recognized public benchmark datasets (GWHD, CHSD), ensuring comparability with existing research, and non-public datasets (SHFD, WHSSH) specifically constructed to reflect the practical demands and challenges in regional monitoring scenarios.

- (3)

- Diversity in Crops and Tasks: The datasets cover two major crops (wheat and maize) and encompass multiple tasks such as health status recognition, disease classification, and farmland segmentation, allowing for an initial assessment of the model’s adaptability across crops and tasks.

- (4)

- Controllability at the Current Research Stage: By limiting the number of datasets to four while ensuring comprehensive validation dimensions, this approach facilitates focused analysis of the model’s behavior under key variations (e.g., scale, data characteristics), preventing the dilution of analytical depth due to an excessive number of test sets.

2.2.2. Post-Enhanced Image Dataset

- (1)

- Random horizontal or vertical flipping, enriching the spatial distribution characteristics of farmland [18];

- (2)

- Random rotation between −30° and 30°, enhancing orientation diversity [19];

- (3)

- Random scaling from 0.8 to 1.2, simulating scale variation at different capture distances [19];

- (4)

- Color enhancement through combined adjustments in brightness (0.7–1.3×), contrast (0.7–1.3×), saturation (0.8–1.2×), and sharpness (0.5–1.5×), improving robustness under varying illumination [20];

- (5)

2.2.3. Robustness Testing Dataset

- (1)

- Simulating sensor acquisition noise using uniform noise of varying intensities [19];

- (2)

- Employing spatial filtering techniques such as box blurring and threshold filtering to reproduce image degradation scenarios [21];

- (3)

- Simulating real-world image processing workflows through post-processing methods like de-sharpening masks and detail enhancement [18];

- (4)

- Combining color balance and color temperature adjustment techniques to restore complex lighting conditions [19];

- (5)

- Introducing geometric distortion and other transformations to simulate imaging anomalies [20].

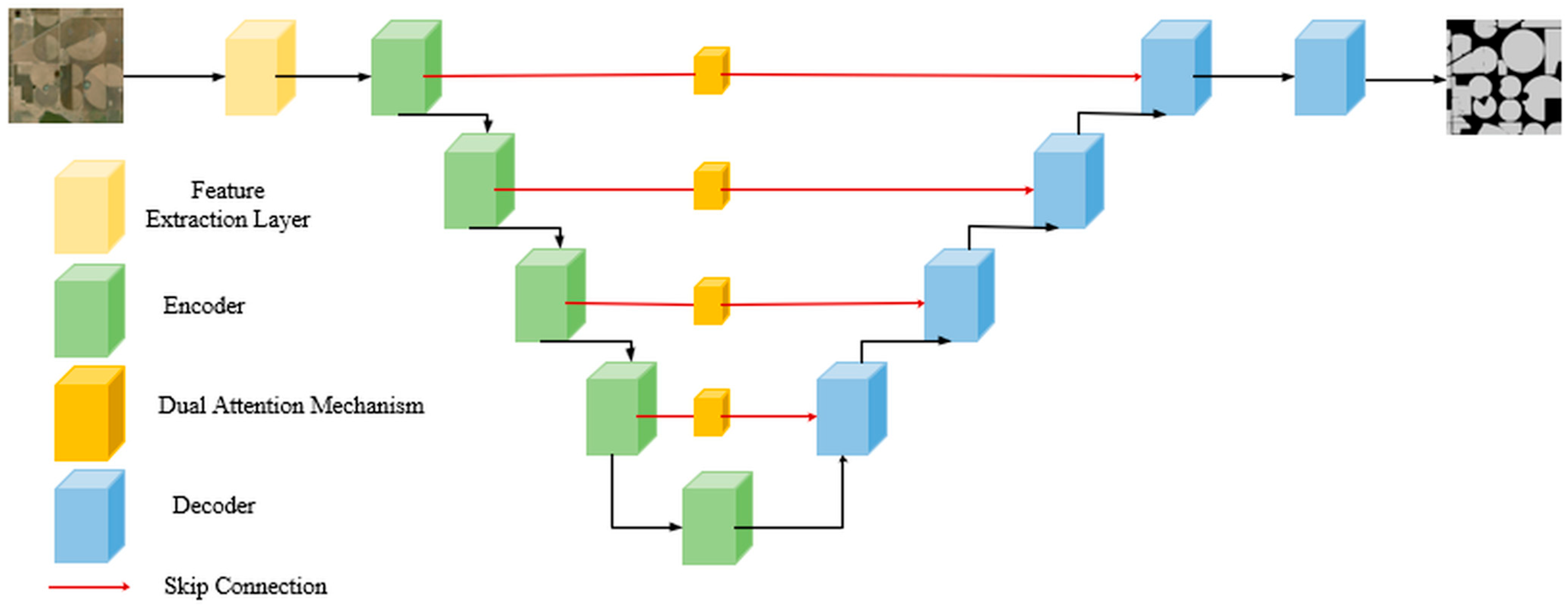

2.3. MAF-RecNet

2.3.1. Overall Architecture

2.3.2. Preprocessing Module

2.3.3. Skeleton Model

2.3.4. Hybrid Attention

2.3.5. Decoder

2.3.6. Skip Connections

2.3.7. Loss Function and Optimizer

2.4. Model Performance and Reliability Evaluation

2.4.1. Hardware Configuration and Evaluation Metrics

2.4.2. Comparative Experiment

2.4.3. Ablation Studies

2.4.4. Generalization Capability Testing

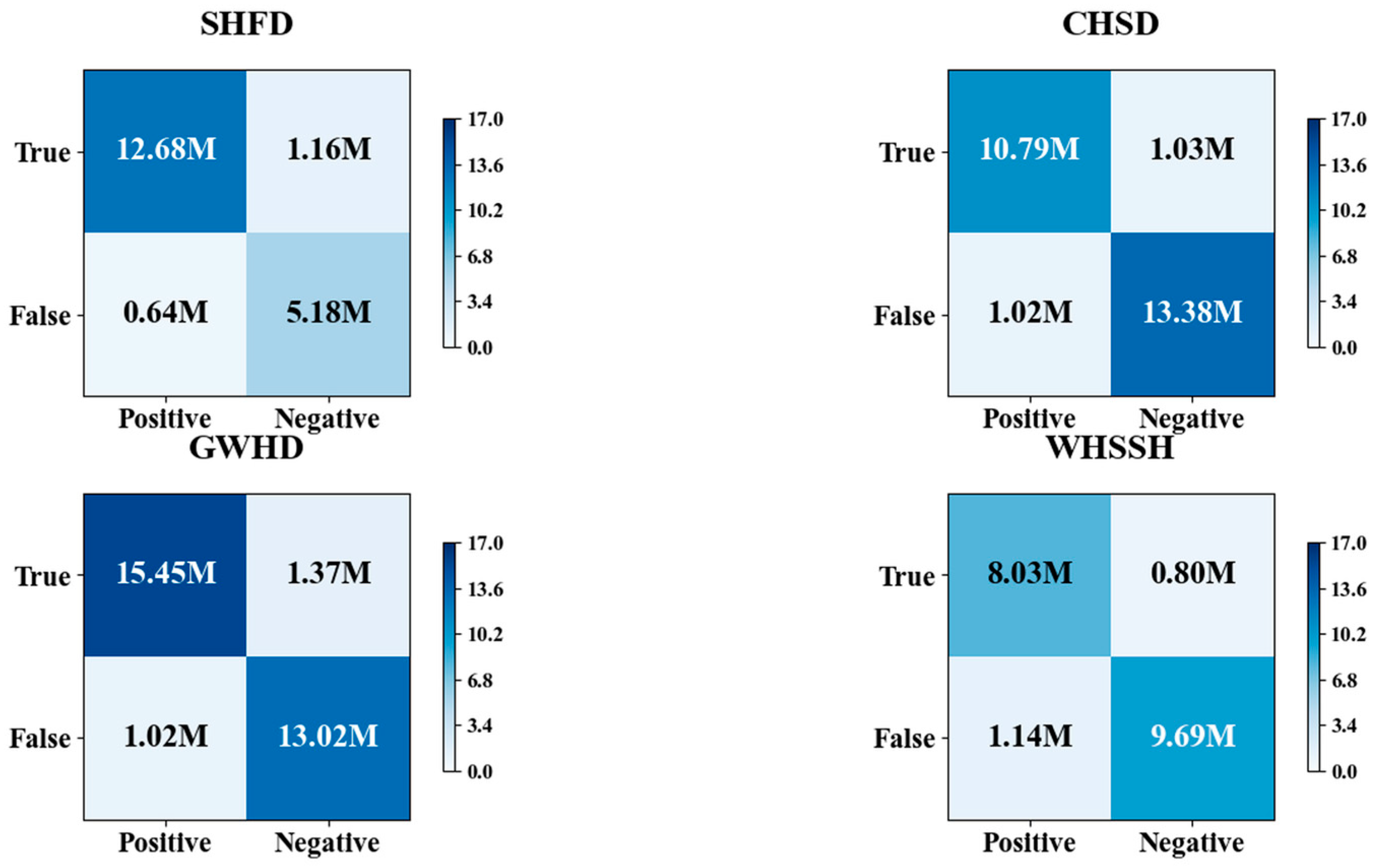

2.4.5. Confusion Matrix Analysis

2.4.6. Robustness Testing

3. Results

3.1. Comparative Experimental Results

3.2. Ablation Study Results

3.3. Generalization Capability Test Results

3.4. Confusion Matrix Analysis Results

3.5. Robustness Test Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of Sample Quality on Recognition Accuracy and Generalization

4.2. Deciphering the Contribution Mechanisms of Attention Modules via Ablation Studies

4.3. Model Limitations and Future Directions

- (1)

- Model Lightweighting and Efficiency Optimization: Explore efficient attention module designs combined with neural architecture search (NAS) techniques to reduce model size and computational overhead while maintaining accuracy, thereby meeting stricter requirements for embedded deployment.

- (2)

- Few-shot and Weakly Supervised Learning Frameworks: Develop more effective image augmentation and synthetic data methods to reduce reliance on large-scale, high-quality annotations, thereby enhancing learning efficiency and model robustness in data-scarce scenarios.

- (3)

- Integrating hyperspectral and LiDAR technologies—particularly emerging hyperspectral LiDAR systems—enables simultaneous 3D hyperspectral data collection, allowing detailed characterization of crop biochemical and structural traits. This helps minimize spatial aggregation errors and enhances monitoring accuracy and adaptability in complex field environments.

- (4)

- Cross-domain Adaptation and Generalization Enhancement: Develop lightweight domain adaptation algorithms to improve model transferability across geographic regions, imaging conditions, and climatic backgrounds, thereby strengthening real-world generalization and robustness.

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- MAF-RecNet achieves an effective balance between recognition accuracy and model efficiency. For farmland identification in southern Hebei, it attains an mIoU of 87.57% and a mAP of 95.42%, outperforming mainstream models such as SegNeXt. Through the synergistic design of multi-level attention mechanisms and lightweight components, the model achieves high-precision recognition with only 15.25 million parameters.

- (2)

- Ablation experiments validate the effectiveness of each module: coordinate attention enhances spatial perception of small-target boundaries, integrated attention improves discriminative representation of multi-scale features, and dual-attention skip connections optimize feature fusion. The collaborative operation of these modules provides essential support for model performance.

- (3)

- The model demonstrates strong cross-task generalization and robustness. In the global wheat-health identification task, it achieves an mIoU of 90.20% and an mAP of 98.28%, reflecting effective knowledge transfer. Moreover, it maintains stable performance under noise-interference robustness testing, verifying its practicality in complex agricultural environments.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karthikeyan, L.; Chawla, I.; Mishra, A.K. A review of remote sensing applications in agriculture for food security: Crop growth and yield, irrigation, and crop losses. J. Hydrol. 2020, 586, 124905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Li, X.; Xiong, Y.; He, M.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, C.; Yao, X.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, W.; Cheng, T. Annual winter wheat mapping for unveiling spatiotemporal patterns in China with a knowledge-guided approach and multi-source datasets. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 225, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Fu, Y.; Wang, J.; Tian, H.; Fu, S.; Niu, Z.; Han, W.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, J.; Yuan, W. Early-season mapping of winter wheat in China based on Landsat and Sentinel images. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 3081–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, M.; Qin, W.; Bilal, M. A High-Precision Aerosol Retrieval Algorithm (HiPARA) for Advanced Himawari Imager (AHI) data: Development and verification. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 253, 112221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Cheng, Q.; Chen, L.; Zhang, B.; Guo, S.; Zhou, X.; Chen, Z. Predicting Winter Wheat Yield with Dual-Year Spectral Fusion, Bayesian Wisdom, and Cross-Environmental Validation. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; McCarthy, C.; Humpal, J.; Percy, C. Near-infrared spectroscopy and deep neural networks for early common root rot detection in wheat from multi-season trials. Agron. J. 2024, 116, 2370–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Qian, X.; Shang, S.; Wan, H. Multi-year mapping of cropping systems in regions with smallholder farms from Sentinel-2 images in Google Earth engine. GISci. Remote Sens. 2024, 61, 2309843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldvai, L.; Mesterházi, P.Á.; Teschner, G.; Nyéki, A. Weed Detection and Classification with Computer Vision Using a Limited Image Dataset. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niloofar, P.; Francis, D.P.; Lazarova-Molnar, S.; Vulpe, A.; Vochin, M.-C.; Suciu, G.; Balanescu, M.; Anestis, V.; Bartzanas, T. Data-driven decision support in livestock farming for improved animal health, welfare and greenhouse gas emissions: Overview and challenges. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 190, 106406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, N.; Sun, X. WeedVision: A single-stage deep learning architecture to perform weed detection and segmentation using drone-acquired images. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 219, 108792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsini, L.; Muñoz López, C.A.; Bhonsale, S.; Roufou, S.; Griffin, S.; Valdramidis, V.; Akkermans, S.; Polanska, M.; Van Impe, J. Modeling climatic effects on milk production. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 225, 109218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, M.; Sun, J.; Guoyang, H.; Niu, A.; Hu, Y.; Yan, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y. FSCFNet: Lightweight neural networks via multi-dimensional importance-aware optimization. Neurocomputing 2026, 660, 131823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Pan, Y.; Hu, T.; Zhang, D.; Dai, J. An Integrated Sample-Free Method for Agricultural Field Delineation From High-Resolution Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 13112–13134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, L.; Yang, C.; Yao, X.; Fu, B. Soybean cultivation and crop rotation monitoring based on multi-source remote sensing data and Bi-LSTM enhanced model. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 239, 110959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Qian, L.; Gamba, P. Advances on Multimodal Remote Sensing Foundation Models for Earth Observation Downstream Tasks: A Survey. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Guo, P.; Sun, Y.; Liang, H.; Zhang, X.; Bai, W. Recent Progress on Vegetation Remote Sensing Using Spaceborne GNSS-Reflectometry. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhao, L.; Sun, R.; Yu, T.; Cheng, S.; Wang, M.; Zhu, A.; Li, Q. Estimation and Spatiotemporal Variation Analysis of Net Primary Productivity in the Upper Luanhe River Basin in China From 2001 to 2017 Combining With a Downscaling Method. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Fan, G.; Maimutimin, B. Efficient Image Segmentation of Coal Blocks Using an Improved DIRU-Net Model. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Park, J.; Hong, J.; Sung, H. Runtime Support for Accelerating CNN Models on Digital DRAM Processing-in-Memory Hardware. IEEE Comput. Archit. Lett. 2022, 21, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Bao, W.; Wang, J.; Ma, Y.; Gao, X.; Xiao, G.; Liu, A.; Dong, J.; Liu, X.; Wu, W. A comprehensive evaluation framework for deep model robustness. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 137, 109308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Wang, J.; Zeng, D.; Huang, Y.; Ding, X. Remote Sensing Image Enhancement Using Regularized-Histogram Equalization and DCT. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2015, 12, 2301–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskota, A.; Ghimire, S.; Ghimire, A.; Baskaran, P. Herbguard: An Ensemble Deep Learning Framework With Efficientnet and Vision Transformers for Fine-Grained Classification of Medicinal and Poisonous Plants. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 179333–179350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Liu, H.; Liang, Z.; Chen, P.; Wang, R.; Liu, K. An Anchor-Free Refining Feature Pyramid Network for Dense and Multioriented Wheat Spikes Detection Under UAV. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 5003314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prommakhot, A.; Onshaunjit, J.; Ooppakaew, W.; Samseemoung, G.; Srinonchat, J. Hybrid CNN and Transformer-Based Sequential Learning Techniques for Plant Disease Classification. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 122876–122887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Huang, H.; Qian, H.; Su, S.; Sun, B.; Zuo, Z. SRCANet: Stacked Residual Coordinate Attention Network for Infrared Ship Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5003614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, S.; Xie, Y.; Xie, S.Q.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Robotic Grasp Detection via Residual Efficient Channel Attention and Multiscale Feature Learning. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 7513311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chai, S.; Tian, Y. Detection and Maturity Classification of Dense Small Lychees Using an Improved Kolmogorov–Arnold Network–Transformer. Plants 2025, 14, 3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, S.; Meng, T.; Zheng, X.; Shao, Y.; Hu, G.; Yin, W.; Shen, J.; He, Y. Evaluation of Defects Depth for Metal Sheets Using Four-Coil Excitation Array Eddy Current Sensor and Improved ResNet18 Network. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 18955–18967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Feng, Y.; Sun, X.; Cheng, X. Swin Transformer Based Recognition for Hydraulic Fracturing Microseismic Signals from Coal Seam Roof with Ultra Large Mining Height. Sensors 2025, 25, 6750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahareek, E.A.; Cifci, M.A.; Desuky, A.S. Integrating Convolutional, Transformer, and Graph Neural Networks for Precision Agriculture and Food Security. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Li, Y.; Feng, W.; Zhu, J.; Yan, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, H. CAGM-Seg: A Symmetry-Driven Lightweight Model for Small Object Detection in Multi-Scenario Remote Sensing. Symmetry 2025, 17, 2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Lv, H.; Wang, A.; Yan, S.; Molnar, G.; Yu, L.; Wang, M. CNN-GCN Coordinated Multimodal Frequency Network for Hyperspectral Image and LiDAR Classification. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, D.; Yan, R.; Ni, H. A Multichannel Long-Term External Attention Network for Aeroengine Remaining Useful Life Prediction. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2024, 5, 5130–5140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Weng, T.-H.; Li, L.-H.; Li, K.-C.; Poniszewska-Maranda, A. An Improved Dilated-Transposed Convolution Detector of Weld Proximity Defects. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 157127–157139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Huang, B.; Yang, J.; Radenkovic, M.; Chen, G. Oceanic Eddy Identification Using Pyramid Split Attention U-Net With Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 1500605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Li, B.; Zou, K.; Zhang, B.; Dai, G.; Tsoi, A.C. Dual-Branch Multi-Dimensional Attention Mechanism for Joint Facial Expression Detection and Classification. Sensors 2025, 25, 3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Zhu, D.; Huang, M.; Lin, Q.; Møller-Jensen, L.; Silva, E.A. MSCANet: Multi-Scale Spatial-Channel Attention Network for Urbanization Intelligent Monitoring. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhen, Z.; Chen, S.; Zhang, L.; Cao, L. Dual-Level Attention Relearning for Cross-Modality Rotated Object Detection in UAV RGB–Thermal Imagery. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Ding, X.; Xia, X.; He, Y.; Fang, H.; Yang, B.; Fu, W. Structure-Aware Progressive Multi-Modal Fusion Network for RGB-T Crack Segmentation. J. Imaging 2025, 11, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Yuan, D.; Xu, S.; Zhou, F.; Zhou, Z. MMA-Net: A Semantic Segmentation Network for High-Resolution Remote Sensing Images Based on Multimodal Fusion and Multi-Scale Multi-Attention Mechanisms. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Guo, X.; Lu, Y.; Hu, H.; Wang, F.; Li, R.; Li, X. Phenology-Guided Wheat and Corn Identification in Xinjiang: An Improved U-Net Semantic Segmentation Model Using PCA and CBAM-ASPP. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Mei, S.; Hu, J.; Ma, L.; Hao, S.; Lv, Z. Filter-Wise Mask Pruning and FPGA Acceleration for Object Classification and Detection. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Wu, C. LGCANet: Local–Global and Change-Aware Network via Segment Anything Model for Remote Sensing Images Change Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5629213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarov, I.; Koshevaya, E.; Pechenina, A.; Boyko, G.; Starshinova, A.; Kudlay, D.; Makarova, T.; Mitrofanova, L. A Comparative Analysis of SegFormer, FabE-Net and VGG-UNet Models for the Segmentation of Neural Structures on Histological Sections. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, G.; Wang, Z.; Weng, L.; Lin, H.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, L. Attention Guide Axial Sharing Mixed Attention (AGASMA) Network for Cloud Segmentation and Cloud Shadow Segmentation. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizzi, F.; Saponaro, S.; Giuliano, A.; Talamonti, C.; Ubaldi, L.; Retico, A. Radiomics and Deep Learning Interplay for Predicting MGMT Methylation in Glioblastoma: The Crucial Role of Segmentation Quality. Cancers 2025, 17, 3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Xie, X.; Lin, Z.; Yan, S. Towards Understanding Convergence and Generalization of AdamW. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 6486–6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Xu, J.; Sun, Q.; Lou, Q. An Efficient Vision Mamba–Transformer Hybrid Architecture for Abdominal Multi-Organ Image Segmentation. Sensors 2025, 25, 6785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Ren, X.; Zhai, D.; Wang, X.; Tarif, M. Lights-Transformer: An Efficient Transformer-Based Landslide Detection Model for High-Resolution Remote Sensing Images. Sensors 2025, 25, 3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, B.; Fan, S.; He, X.; Xu, T.; Chang, Y. Small Logarithmic Floating-Point Multiplier Based on FPGA and Its Application on MobileNet. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2022, 69, 5119–5123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Z.; Chao, L.; Chen, Y.; Li, Q. Multi-Feature Decision Fusion Network for Heart Sound Abnormality Detection and Classification. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2024, 28, 1386–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Hao, Z.-W.; Wang, X.-M.; Wang, H.-L.; Yang, J.-M.; Zhou, H.; Wang, X.-D.; Zhang, J.-Y.; Yang, H.-W.; Liu, P.-R.; et al. Dual-Stream Attention-Based Classification Network for Tibial Plateau Fractures via Diffusion Model Augmentation and Segmentation Map Integration. Curr. Med. Sci. 2025, 45, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korfhage, N.; Mühling, M.; Freisleben, B. Search anything: Segmentation-based similarity search via region prompts. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 84, 32593–32618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Ruíz, M.A.; Karabağ, C.; Roman-Rangel, E.; Reyes-Aldasoro, C.C. DRD-UNet, a UNet-Like Architecture for Multi-Class Breast Cancer Semantic Segmentation. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 40412–40424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, C.E.G.; Vieira, S.L.; Paranaiba, C.F.B.; Itikawa, E.N. Breast tumor segmentation in ultrasound images: Comparing U-net and U-net + +. Res. Biomed. Eng. 2025, 41, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jin, Z.; Wu, T. A Spatiotemporal Forecasting Method for Cooling Load of Chillers Based on Patch-Specific Dynamic Filtering. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Wu, J.; Zhao, X.; Luo, Y.; Xu, G. SC-CNN: LiDAR point cloud filtering CNN under slope and copula correlation constraint. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 212, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Shi, S.; Gong, W.; Yang, J.; Du, L.; Song, S.; Chen, B.; Zhang, Z. Evaluation of hyperspectral LiDAR for monitoring rice leaf nitrogen by comparison with multispectral LiDAR and passive spectrometer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Niu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Bi, K.; Fu, Y.; Gao, S.; Wu, M.; Wang, L. Full-waveform hyperspectral LiDAR data decomposition via ranking central locations of natural target echoes (Rclonte) at different wavelengths. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 310, 114227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time | Number of Scenes |

|---|---|

| February | 14 |

| March | 82 |

| April | 7 |

| Total | 103 |

| Dataset Name | Number of Samples | Total Pixels (M) | Target Pixels (M) | Average Target Pixel Ratio per Sample (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHFD | 1500 | 98.3 | 66.63 | 67.78 |

| WHSSH | 1500 | 98.3 | 45.86 | 46.65 |

| GWHD | 2300 | 150.73 | 78.79 | 52.27 |

| CHSD | 2000 | 131.07 | 59.03 | 45.04 |

| Dataset Name | Number of Samples | Total Pixels (M) | Target Pixels (M) | Average Target Pixel Ratio Per Sample (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHFD-RTD | 1800 | 117.96 | 79.77 | 67.62 |

| WHSSH-RTD | 1797 | 117.77 | 54.78 | 46.52 |

| GWHD-RTD | 2758 | 180.75 | 93.8 | 51.89 |

| CHSD-RTD | 2397 | 157.01 | 70.82 | 45.09 |

| Model Name | mPrecsion (%) | mRcall (%) | mF1-Score (%) | mIoU (%) | mAP (%) | Parameters (M) | FLOPs (G) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAF-RecNet | 90.56 | 95.18 | 92.83 | 87.57 | 95.42 | 15.25 | 21.81 |

| MDFNet | 85.13 | 89.47 | 87.26 | 82.32 | 89.69 | 36.18 | 106.16 |

| SegFormer | 76.98 | 80.90 | 78.91 | 74.43 | 81.10 | 3.72 | 31.93 |

| FastSAM | 81.50 | 85.66 | 83.55 | 78.81 | 85.88 | 17.43 | 27.63 |

| SegNeXt | 83.32 | 87.57 | 85.40 | 80.56 | 87.79 | 24.9 | 16.8 |

| Model Name | mPrecision (%) | mRecall (%) | mF1-Score (%) | mIoU (%) | mAP (%) | Parameters (M) | FLOPs (G) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAF-RecNet | 90.56 | 95.18 | 92.83 | 87.57 | 95.42 | 15.25 | 21.81 |

| MA-RecNet | 86.03 | 90.42 | 88.19 | 83.19 | 90.65 | 15.8 | 21.32 |

| M-RecNet | 80.60 | 84.71 | 82.62 | 77.94 | 84.92 | 15.01 | 19.64 |

| U-Net | 72.45 | 76.14 | 74.26 | 70.06 | 76.34 | 13.39 | 14.77 |

| Dataset Name | mPrecision (%) | mRecall (%) | mF1-Score (%) | mIoU (%) | mAP (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHFD | 90.56 | 95.18 | 92.83 | 87.57 | 95.42 |

| WHSSH | 83.32 | 87.57 | 85.40 | 80.56 | 87.79 |

| GWHD | 93.28 | 98.04 | 95.61 | 90.20 | 98.28 |

| CHSD | 86.94 | 91.37 | 89.12 | 84.07 | 91.60 |

| Dataset Name | mPrecision (%) | mRecall (%) | mF1-Score (%) | mIoU (%) | mAP (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHFD-RTD | 80.60 | 84.71 | 82.62 | 77.94 | 84.92 |

| WHSSH-RTD | 75.82 | 79.69 | 77.71 | 73.31 | 79.89 |

| GWHD-RTD | 85.82 | 90.20 | 87.96 | 82.98 | 90.42 |

| CHSD-RTD | 80.85 | 84.97 | 82.88 | 78.19 | 85.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yao, H.; Zhu, J.; Li, Y.; Yan, H.; Feng, W.; Niu, L.; Wu, Z. MAF-RecNet: A Lightweight Wheat and Corn Recognition Model Integrating Multiple Attention Mechanisms. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 497. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030497

Yao H, Zhu J, Li Y, Yan H, Feng W, Niu L, Wu Z. MAF-RecNet: A Lightweight Wheat and Corn Recognition Model Integrating Multiple Attention Mechanisms. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(3):497. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030497

Chicago/Turabian StyleYao, Hao, Ji Zhu, Yancang Li, Haiming Yan, Wenzhao Feng, Luwang Niu, and Ziqi Wu. 2026. "MAF-RecNet: A Lightweight Wheat and Corn Recognition Model Integrating Multiple Attention Mechanisms" Remote Sensing 18, no. 3: 497. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030497

APA StyleYao, H., Zhu, J., Li, Y., Yan, H., Feng, W., Niu, L., & Wu, Z. (2026). MAF-RecNet: A Lightweight Wheat and Corn Recognition Model Integrating Multiple Attention Mechanisms. Remote Sensing, 18(3), 497. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030497