Parsing the Relative Contributions of Leaf and Canopy Traits in Airborne Spectrometer Measurements

Highlights

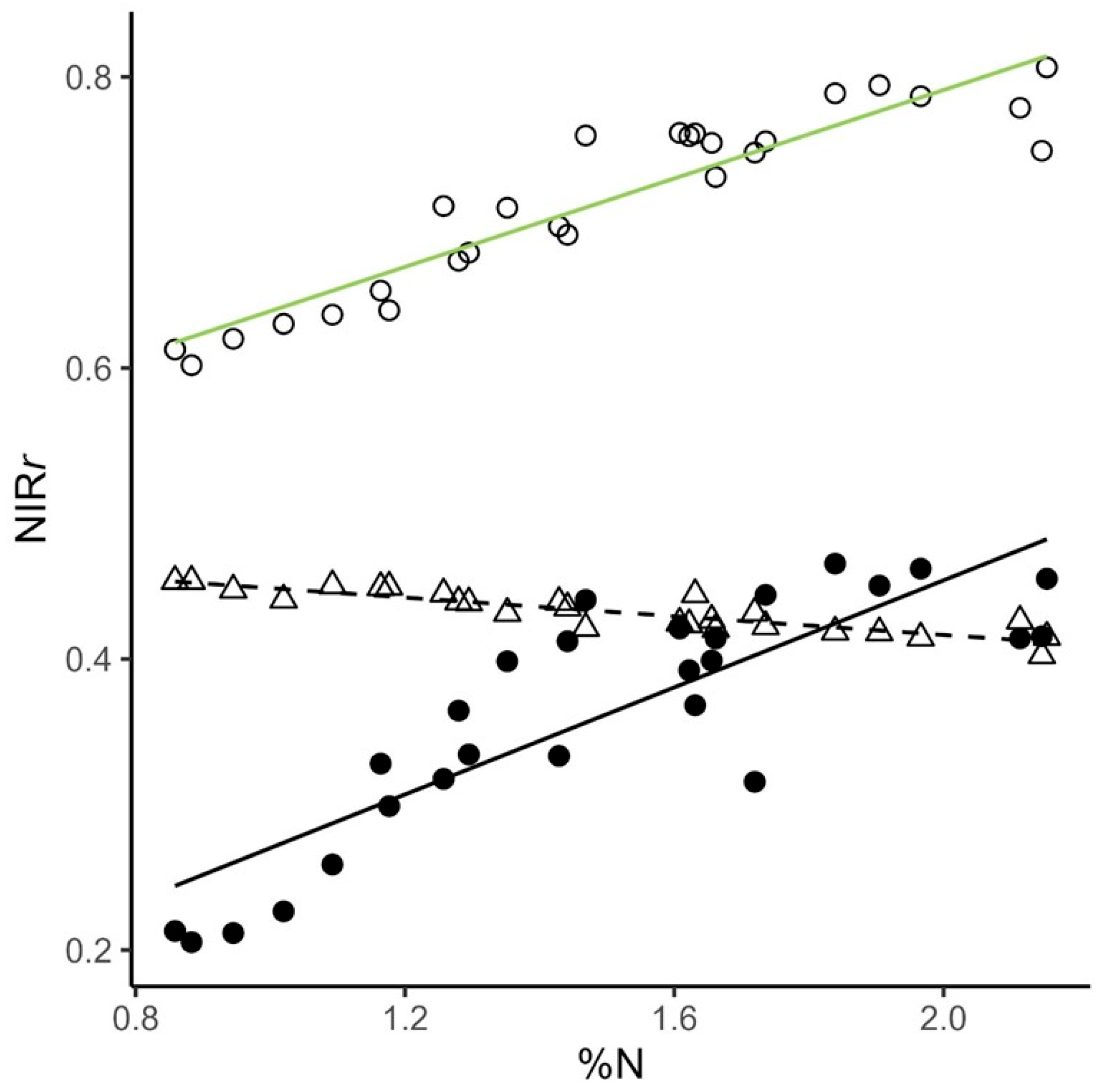

- We validated a model of potential canopy reflectance representing a structural simplified canopy using LAI-weighted optical properties, and showed a strong positive relationship with canopy %N.

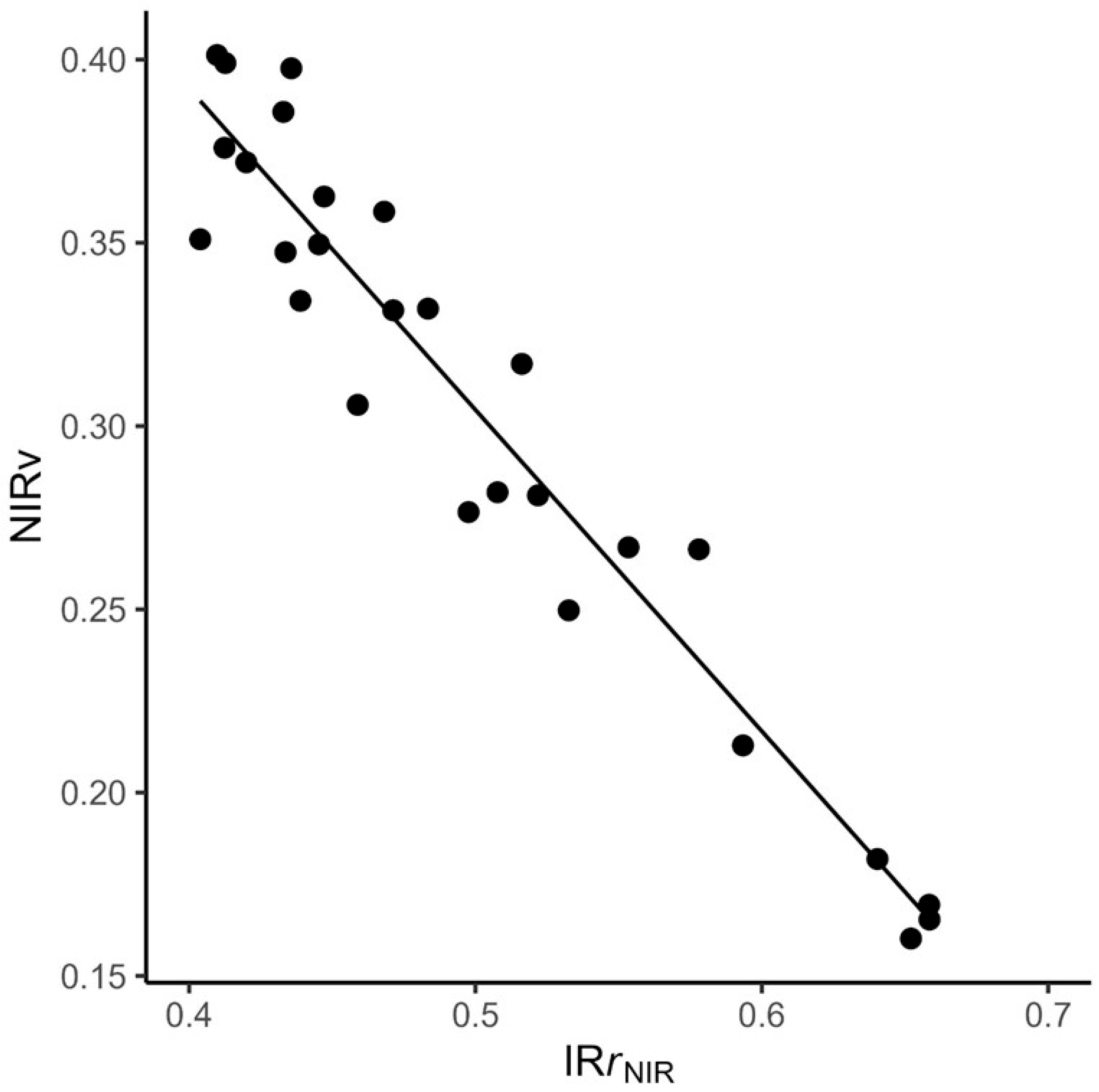

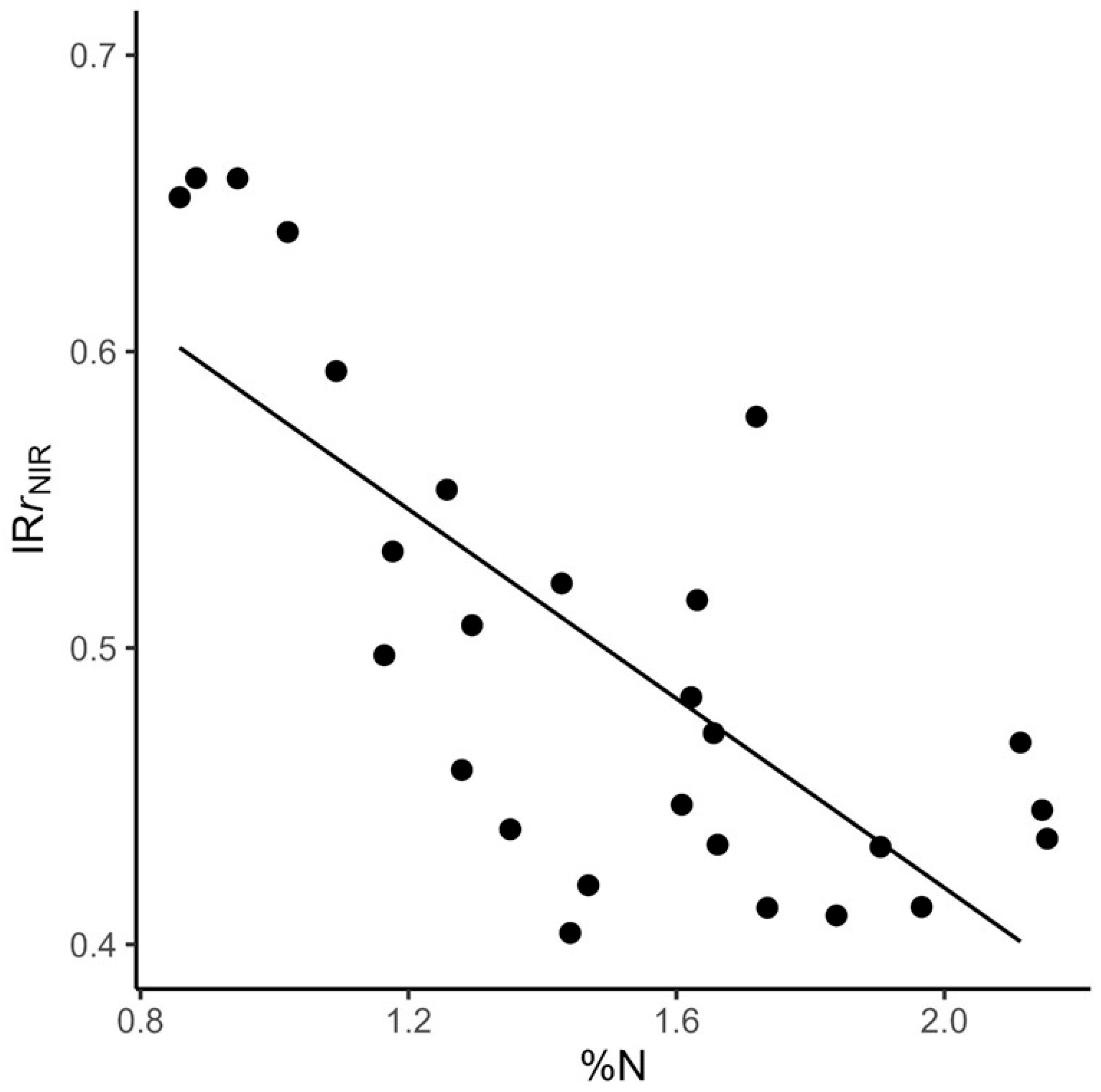

- We derived an index of relative reflectance to quantify the effect of canopy structural complexity on whole-canopy reflectance and found that complexity reduces potential canopy NIR reflectance more in low %N stands high %N stands.

- The positive correlation between canopy %N and LAI-weighted leaf NIR reflectance suggests that the relationship between canopy %N and canopy NIR reflectance arises from the integrated effects of canopy complexity acting on differences in leaf-level optical traits.

- The physical mechanism or mechanisms underlying the relationship between canopy complexity and canopy %N require further study, but implies existing links between ecosystem biochemistry, leaf traits, and canopy growth patterns.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

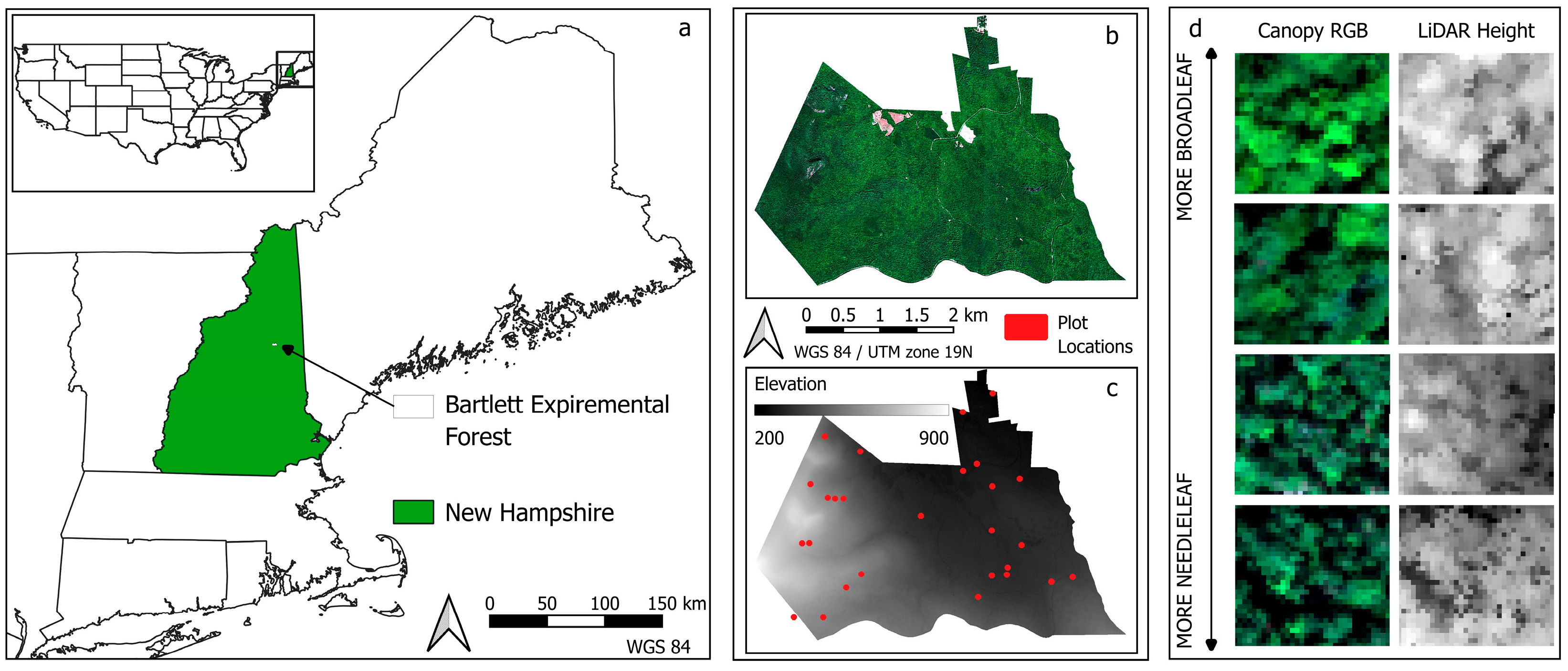

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Field and Lab Measurements

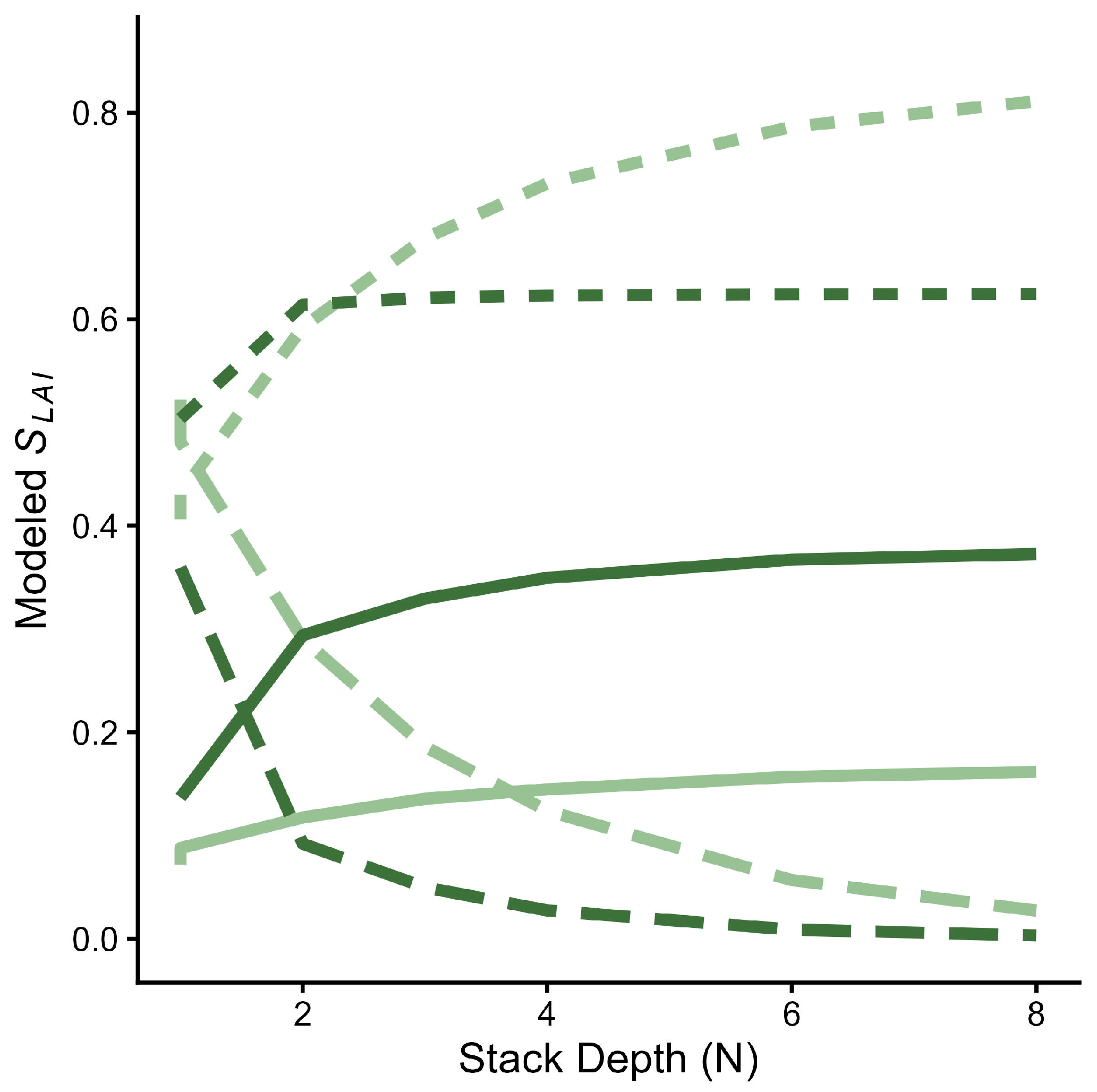

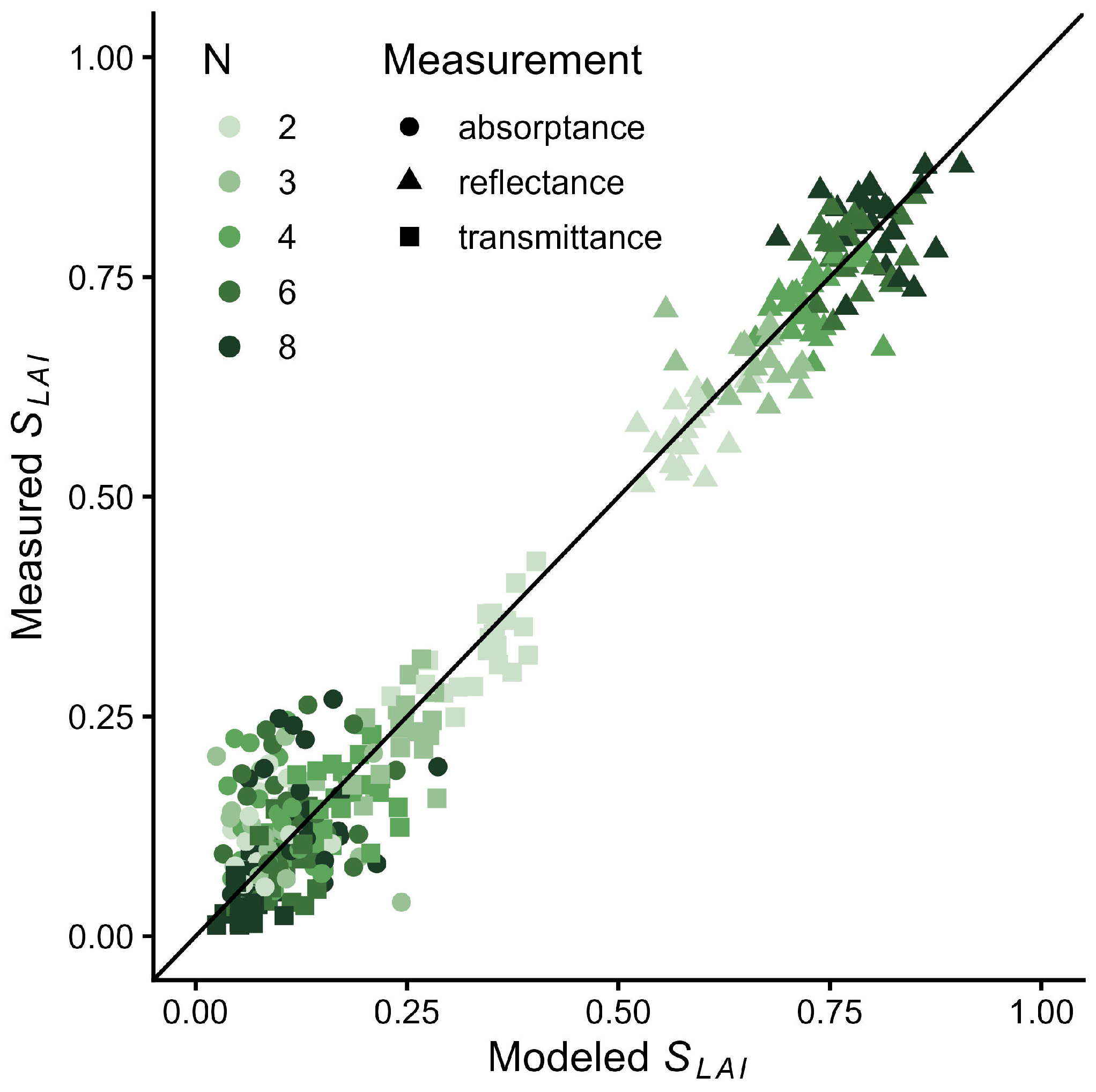

2.3. Leaf Stack Reflectance Model

2.4. Remote Sensing Characterization of Study Plots

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Leaf Traits on Leaf and Leaf Stack Reflectance

4.2. Using IRr to Evaluate Links Between Canopy %N, NIRr, and Canopy Complexity

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kokaly, R.F.; Asner, G.P.; Ollinger, S.V.; Martin, M.E.; Wessman, C.A. Characterizing Canopy Biochemistry from Imaging Spectroscopy and Its Application to Ecosystem Studies. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113, S78–S91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loozen, Y.; Rebel, K.T.; de Jong, S.M.; Lu, M.; Ollinger, S.V.; Wassen, M.J.; Karssenberg, D. Mapping Canopy Nitrogen in European Forests Using Remote Sensing and Environmental Variables with the Random Forests Method. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 247, 111933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollinger, S.V.; Smith, M.-L. Net Primary Production and Canopy Nitrogen in a Temperate Forest Landscape: An Analysis Using Imaging Spectroscopy, Modeling and Field Data. Ecosystems 2005, 8, 760–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepine, L.C.; Ollinger, S.V.; Ouimette, A.P.; Martin, M.E. Examining Spectral Reflectance Features Related to Foliar Nitrogen in Forests: Implications for Broad-Scale Nitrogen Mapping. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 173, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, F.B.; Ollinger, S.V.; Martin, M.E.; Ducey, M.J.; Lepine, L.C.; Wicklein, H.F. Foliar Nitrogen in Relation to Plant Traits and Reflectance Properties of New Hampshire Forests. Can. J. For. Res. 2013, 43, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollinger, D.Y.; Ollinger, S.V.; Richardson, A.D.; Meyers, T.P.; Dail, D.B.; Martin, M.E.; Scott, N.A.; Arkebauer, T.J.; Baldocchi, D.D.; Clark, K.L.; et al. Albedo Estimates for Land Surface Models and Support for a New Paradigm Based on Foliage Nitrogen Concentration. Glob. Change Biol. 2010, 16, 696–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.E.; Plourde, L.C.; Ollinger, S.V.; Smith, M.-L.; McNeil, B.E. A Generalizable Method for Remote Sensing of Canopy Nitrogen across a Wide Range of Forest Ecosystems. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 3511–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollinger, S.V.; Richardson, A.D.; Martin, M.E.; Hollinger, D.Y.; Frolking, S.E.; Reich, P.B.; Plourde, L.C.; Katul, G.G.; Munger, J.W.; Oren, R.; et al. Canopy Nitrogen, Carbon Assimilation, and Albedo in Temperate and Boreal Forests: Functional Relations and Potential Climate Feedbacks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 19336–19341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badgley, G.; Anderegg, L.D.L.; Berry, J.A.; Field, C.B. Terrestrial Gross Primary Production: Using NIRV to Scale from Site to Globe. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 3731–3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badgley, G.; Field, C.B.; Berry, J.A. Canopy Near-Infrared Reflectance and Terrestrial Photosynthesis. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1602244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldocchi, D.D.; Ryu, Y.; Dechant, B.; Eichelmann, E.; Hemes, K.; Ma, S.; Sanchez, C.R.; Shortt, R.; Szutu, D.; Valach, A.; et al. Outgoing Near-Infrared Radiation from Vegetation Scales with Canopy Photosynthesis Across a Spectrum of Function, Structure, Physiological Capacity, and Weather. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2020, 125, e2019JG005534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollinger, S.V. Sources of Variability in Canopy Reflectance and the Convergent Properties of Plants. New Phytol. 2011, 189, 375–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollinger, S.V.; Reich, P.B.; Frolking, S.; Lepine, L.C.; Hollinger, D.Y.; Richardson, A.D. Nitrogen Cycling, Forest Canopy Reflectance, and Emergent Properties of Ecosystems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolster, K.L.; Martin, M.E.; Aber, J.D. Determination of Carbon Fraction and Nitrogen Concentration in Tree Foliage by near Infrared Reflectances: A Comparison of Statistical Methods. Can. J. For. Res. 1996, 26, 590–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, D.M.; Keegan, H.J.; Schleter, J.C.; Weidner, V.R. Spectral Properties of Plants. Appl. Opt. 1965, 4, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquemoud, S.; Baret, F. PROSPECT: A Model of Leaf Optical Properties Spectra. Remote Sens. Environ. 1990, 34, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.K.; Ollinger, S.V.; Hollinger, D.Y.; Wicklein, H.F.; Richardson, A.D. Canopy-Scale Relationships between Foliar Nitrogen and Albedo Are Not Observed in Leaf Reflectance and Transmittance within Temperate Deciduous Tree Species. Botany 2011, 89, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicklein, H.F.; Ollinger, S.V.; Martin, M.E.; Hollinger, D.Y.; Lepine, L.C.; Day, M.C.; Bartlett, M.K.; Richardson, A.D.; Norby, R.J. Variation in Foliar Nitrogen and Albedo in Response to Nitrogen Fertilization and Elevated CO2. Oecologia 2012, 169, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, C.M.; Atkins, J.W.; Fahey, R.T.; Hardiman, B.S. High Rates of Primary Production in Structurally Complex Forests. Ecology 2019, 100, e02864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuermann, C.M.; Nave, L.E.; Fahey, R.T.; Nadelhoffer, K.J.; Gough, C.M. Effects of Canopy Structure and Species Diversity on Primary Production in Upper Great Lakes Forests. Oecologia 2018, 188, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, C.M.; Atkins, J.W.; Fahey, R.T.; Hardiman, B.S.; LaRue, E.A. Community and Structural Constraints on the Complexity of Eastern North American Forests. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2020, 29, 2107–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, J.W.; Fahey, R.T.; Hardiman, B.S.; Gough, C.M. Forest Canopy Structural Complexity and Light Absorption Relationships at the Subcontinental Scale. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2018, 123, 1387–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinemets, Ü. A Review of Light Interception in Plant Stands from Leaf to Canopy in Different Plant Functional Types and in Species with Varying Shade Tolerance. Ecol. Res. 2010, 25, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinemets, Ü.; Cescatti, A.; Lukjanova, A.; Tobias, M.; Truus, L. Modification of Light-Acclimation of Pinus Sylvestris Shoot Architecture by Site Fertility. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2002, 111, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Close, D.C.; Beadle, C.L. Leaf Angle Responds to Nitrogen Supply in Eucalypt Seedlings. Is It a Photoprotective Mechanism? Tree Physiol. 2006, 26, 743–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béland, M.; Baldocchi, D. Is Foliage Clumping an Outcome of Resource Limitations within Forests? Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 295, 108185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béland, M.; Kobayashi, H. Drivers of Deciduous Forest Near-Infrared Reflectance: A 3D Radiative Transfer Modeling Exercise Based on Ground Lidar. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 302, 113951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducey, M.J.; Fraser, O.L.; Yamasaki, M.; Belair, E.P.; Leak, W.B. Eight Decades of Compositional Change in a Managed Northern Hardwood Landscape. For. Ecosyst. 2023, 10, 100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillargeon, K.A.; Ouimette, A.P.; Hastings, J.H.; Sanders-DeMott, R.; Ollinger, S.V. Regional and Local Variation in Chemical, Structural, and Physical Leaf Traits for Tree Species in the Northeastern United States; Environmental Data Initiative: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 Years of Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aber, J.D. Foliage-Height Profiles and Succession in Northern Hardwood Forests. Ecology 1979, 60, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragg, J.G.; Uhler, R.S. The Demand for Automobiles. Can. J. Econ. Rev. Can. d’Econ. 1970, 3, 386–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, F.B.; Ducey, M.J.; Orwig, D.A.; Cook, B.; Palace, M.W. Comparison of Lidar- and Allometry-Derived Canopy Height Models in an Eastern Deciduous Forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 406, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, G.G. On the Intensity of the Light Reflected from or Transmitted through a Pile of Plates. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 1860, 11, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquemoud, S.; Ustin, S. Modeling Leaf Optical Properties: Prospect. In Leaf Optical Properties; Jacquemoud, S., Ustin, S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 265–291. ISBN 978-1-108-48126-7. [Google Scholar]

- Benford, F. Radiation in a Diffusing Medium. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1946, 36, 524–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, T.P.; Curran, P.J.; Plummer, S.E. LIBERTY—Modeling the Effects of Leaf Biochemical Concentration on Reflectance Spectra. Remote Sens. Environ. 1998, 65, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON). Spectrometer Orthorectified Surface Directional Reflectance—Mosaic (DP3.30006.001): RELEASE-2023; National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON): Boulder, CO, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON). Discrete Return LiDAR Point Cloud (DP1.30003.001), RELEASE-2023; National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON): Boulder, CO, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.-L.; Martin, M.E.; Plourde, L.; Ollinger, S.V. Analysis of hyperspectral data for estimation of temperate forest canopy nitrogen concentration: Comparison between an airborn (AVIRIS) and a spaceborne (Hyperion) sensor. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2003, 41, 1332–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardiman, B.S.; Bohrer, G.; Gough, C.M.; Curtis, P.S. Canopy Structural Changes Following Widespread Mortality of Canopy Dominant Trees. Forests 2013, 4, 537–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, V.R.; Bakker, J.D.; McGaughey, R.J.; Lutz, J.A.; Gersonde, R.F.; Franklin, J.F. Examining Conifer Canopy Structural Complexity across Forest Ages and Elevations with LiDAR Data. Can. J. For. Res. 2010, 40, 774–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.G.; Russ, M.E. The Canopy Surface and Stand Development: Assessing Forest Canopy Structure and Complexity with near-Surface Altimetry. For. Ecol. Manag. 2004, 189, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamoske, A.G.; Dahlin, K.M.; Serbin, S.P.; Stark, S.C. Leaf Traits and Canopy Structure Together Explain Canopy Functional Diversity: An Airborne Remote Sensing Approach. Ecol. Appl. 2021, 31, e02230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefsky, M.A.; Cohen, W.B.; Acker, S.A.; Parker, G.G.; Spies, T.A.; Harding, D. Lidar Remote Sensing of the Canopy Structure and Biophysical Properties of Douglas-Fir Western Hemlock Forests. Remote Sens. Environ. 1999, 70, 339–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venables, W.N.; Ripley, B.D. Modern Applied Statistics with S, 4th ed.; Statistics and Computing, Statistics, Computing Venables, W.N.: Statistics w.S-PLUS; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-387-95457-8. [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemoud, S.; Verhoef, W.; Baret, F.; Bacour, C.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Asner, G.P.; François, C.; Ustin, S.L. PROSPECT + SAIL Models: A Review of Use for Vegetation Characterization. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113, S56–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knyazikhin, Y.; Martonchik, J.V.; Myneni, R.B.; Diner, D.J.; Running, S.W. Synergistic Algorithm for Estimating Vegetation Canopy Leaf Area Index and Fraction of Absorbed Photosynthetically Active Radiation from MODIS and MISR Data. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1998, 103, 32257–32275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenberg, P.; Mõttus, M.; Rautiainen, M. Photon Recollision Probability in Modelling the Radiation Regime of Canopies—A Review. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 183, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, B.E.; Fahey, R.T.; King, C.J.; Erazo, D.A.; Heimerl, T.Z.; Elmore, A.J. Tree Crown Economics. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2023, 21, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Badgley, G.; Dechant, B.; Ryu, Y.; Chen, M.; Berry, J.A. A Practical Approach for Estimating the Escape Ratio of Near-Infrared Solar-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 232, 111209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daughtry, C.S.T.; Biehl, L.L.; Ranson, K.J. A New Technique to Measure the Spectral Properties of Conifer Needles. Remote Sens. Environ. 1989, 27, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesarch, M.A.; Walter-Shea, E.A.; Asner, G.P.; Middleton, E.M.; Chan, S.S. A Revised Measurement Methodology for Conifer Needles Spectral Optical Properties: Evaluating the Influence of Gaps between Elements. Remote Sens. Environ. 1999, 68, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, H.M.; Motohka, T.; Murakami, K.; Muraoka, H.; Nasahara, K.N. Accurate Measurement of Optical Properties of Narrow Leaves and Conifer Needles with a Typical Integrating Sphere and Spectroradiometer. Plant Cell Environ. 2013, 36, 1903–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuwirthová, E.; Lhotáková, Z.; Albrechtová, J. The Effect of Leaf Stacking on Leaf Reflectance and Vegetation Indices Measured by Contact Probe during the Season. Sensors 2017, 17, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovi, A.; Schraik, D.; Hanuš, J.; Homolová, L.; Juola, J.; Lang, M.; Lukeš, P.; Pisek, J.; Rautiainen, M. Assessment of a Photon Recollision Probability Based Forest Reflectance Model in European Boreal and Temperate Forests. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 269, 112804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, I.J.; Reich, P.B.; Westoby, M.; Ackerly, D.D.; Baruch, Z.; Bongers, F.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Chapin, T.; Cornelissen, J.H.; Diemer, M.; et al. The Worldwide Leaf Economics Spectrum. Nature 2004, 428, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, C.; Mooney, H.A. Leaf Age and Seasonal Effects on Light, Water, and Nitrogen Use Efficiency in a California Shrub. Oecologia 1983, 56, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikosaka, K.; Hanba, Y.T.; Hirose, T.; Terashima, I. Photosynthetic Nitrogen-Use Efficiency in Leaves of Woody and Herbaceous Species. Funct. Ecol. 1998, 12, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorter, H.; Evans, J.R. Photosynthetic Nitrogen-Use Efficiency of Species That Differ Inherently in Specific Leaf Area. Oecologia 1998, 116, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Yan, Z.; Majcher, B.M.; Lee, C.K.F.; Zhao, Y.; Song, G.; Wang, B.; Wang, X.; Deng, Y.; Michaletz, S.T.; et al. Dynamic Biotic Controls of Leaf Thermoregulation across the Diel Timescale. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 315, 108827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautiainen, M.; Lukeš, P.; Homolová, L.; Hovi, A.; Pisek, J.; Mõttus, M. Spectral Properties of Coniferous Forests: A Review of In Situ and Laboratory Measurements. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, B.N.; Williams, D.L.; Moss, D.M.; Lauten, G.N.; Kim, M. High-Spectral Resolution Field and Laboratory Optical Reflectance Measurements of Red Spruce and Eastern Hemlock Needles and Branches. Remote Sens. Environ. 1994, 47, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, A.; Carter, G. Variability in Leaf Optical Properties among 26 Species from a Broad Range of Habitats. Am. J. Bot. 1998, 85, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinemets, U.; Al Afas, N.; Cescatti, A.; Pellis, A.; Ceulemans, R. Petiole Length and Biomass Investment in Support Modify Light Interception Efficiency in Dense Poplar Plantations. Tree Physiol. 2004, 24, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knyazikhin, Y.; Schull, M.A.; Stenberg, P.; Mõttus, M.; Rautiainen, M.; Yang, Y.; Marshak, A.; Latorre Carmona, P.; Kaufmann, R.K.; Lewis, P.; et al. Hyperspectral Remote Sensing of Foliar Nitrogen Content. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E185–E192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautiainen, M.; Stenberg, P. Application of Photon Recollision Probability in Coniferous Canopy Reflectance Simulations. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 96, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolander, S.; Stenberg, P. A Method to Account for Shoot Scale Clumping in Coniferous Canopy Reflectance Models. Remote Sens. Environ. 2003, 88, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Brewer, C.A. The Adaptive Importance of Shoot and Crown Architecture in Conifer Trees. Am. Nat. 1994, 143, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Carter, G.A. Shoot Structural Effects on Needle Temperatures and Photosynthesis in Conifers. Am. J. Bot. 1988, 75, 496–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinemets, Ü.; Lukjanova, A. Needle Longevity, Shoot Growth and Branching Frequency in Relation to Site Fertility and within-Canopy Light Conditions in Pinus Sylvestris. Ann. For. Sci. 2003, 60, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellsworth, D.S.; Reich, P.B. Canopy Structure and Vertical Patterns of Photosynthesis and Related Leaf Traits in a Deciduous Forest. Oecologia 1993, 96, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valladares, F.; Niinemets, Ü. Shade Tolerance, a Key Plant Feature of Complex Nature and Consequences. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2008, 39, 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litton, C.M.; Raich, J.W.; Ryan, M.G. Carbon Allocation in Forest Ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2007, 13, 2089–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dybzinski, R.; Farrior, C.E.; Pacala, S.W. Increased Forest Carbon Storage with Increased Atmospheric CO2 despite Nitrogen Limitation: A Game-Theoretic Allocation Model for Trees in Competition for Nitrogen and Light. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 1182–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducey, M.J. Evergreenness and Wood Density Predict Height–Diameter Scaling in Trees of the Northeastern United States. For. Ecol. Manag. 2012, 279, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Y.; Pastor, J. Interactions Among Nitrogen, Carbon, Plant Shape, and Photosynthesis. Am. Nat. 1996, 147, 847–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kergoat, L.; Lafont, S.; Arneth, A.; Le Dantec, V.; Saugier, B. Nitrogen Controls Plant Canopy Light-Use Efficiency in Temperate and Boreal Ecosystems. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2008, 113, G04017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chianucci, F.; Pisek, J.; Raabe, K.; Marchino, L.; Ferrara, C.; Corona, P. A Dataset of Leaf Inclination Angles for Temperate and Boreal Broadleaf Woody Species. Ann. For. Sci. 2018, 75, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattenborn, T.; Richter, R.; Guimarães-Steinicke, C.; Feilhauer, H.; Wirth, C. AngleCam: Predicting the Temporal Variation of Leaf Angle Distributions from Image Series with Deep Learning. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2022, 13, 2531–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, B.E.; Pisek, J.; Lepisk, H.; Flamenco, E.A. Measuring Leaf Angle Distribution in Broadleaf Canopies Using UAVs. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2016, 218–219, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.A. The Functional Significance of Leaf Angle in Eucalyptus. Aust. J. Bot. 1997, 45, 619–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reaves, V.C.; Elmore, A.J.; Nelson, D.M.; McNeil, B.E. Drivers of Spatial Variability in Greendown within an Oak-Hickory Forest Landscape. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 210, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.G.; Chen, Y.N.; Li, W.H.; Chen, X.L.; He, G.Z. Heliotropic Leaf Movement of Sophora alopecuroides L.: An Efficient Strategy to Optimise Photochemical Performance. Photosynthetica 2015, 53, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattenborn, T.; Wieneke, S.; Montero, D.; Mahecha, M.D.; Richter, R.; Guimarães-Steinicke, C.; Wirth, C.; Ferlian, O.; Feilhauer, H.; Sachsenmaier, L.; et al. Temporal Dynamics in Vertical Leaf Angles Can Confound Vegetation Indices Widely Used in Earth Observations. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuwirthová, E.; Lhotáková, Z.; Červená, L.; Lukeš, P.; Campbell, P.; Albrechtová, J. Asymmetry of Leaf Internal Structure Affects PLSR Modelling of Anatomical Traits Using VIS-NIR Leaf Level Spectra. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2024, 57, 2292154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, R.; Jablonski, A.; Stovall, A.; Kim, J.; Yi, K.; Ma, Y.; Beverly, D.; Phillips, R.; Novick, K.; et al. Leaf Angle as a Leaf and Canopy Trait: Rejuvenating Its Role in Ecology with New Technology. Ecol. Lett. 2023, 26, 1005–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.; Hunsaker, A.G.; Jacobs, J.M.; Palace, M.; Sullivan, F.B.; Burakowski, E.A. Maximum Entropy Modeling to Identify Physical Drivers of Shallow Snowpack Heterogeneity Using Unpiloted Aerial System (UAS) Lidar. J. Hydrol. 2021, 602, 126722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, J.H.; Ollinger, S.V.; Ouimette, A.P.; Sanders-DeMott, R.; Palace, M.W.; Ducey, M.J.; Sullivan, F.B.; Basler, D.; Orwig, D.A. Tree Species Traits Determine the Success of LiDAR-Based Crown Mapping in a Mixed Temperate Forest. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, F.B.; Hunsaker, A.G.; Palace, M.W.; Jacobs, J.M. Evaluating the Effects of UAS Flight Speed on Lidar Snow Depth Estimation in a Heterogeneous Landscape. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilker, T.; Gitelson, A.; Coops, N.C.; Hall, F.G.; Black, T.A. Tracking Plant Physiological Properties from Multi-Angular Tower-Based Remote Sensing. Oecologia 2011, 165, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Data Type | Abbreviation | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperspectral | NIRrC | NIR reflectance of incident solar radiation of forest canopies |

| NIRrLAI | LAI-weighted NIR reflectance of leaves | |

| NIRrL | NIR reflectance of leaves, weighted by canopy composition | |

| IRr | Index of relative reflectance | |

| Lidar-derived structural metrics | Rumple | Surface roughness; surface area divided by projected area (Kane et al. [42]) |

| Rugosity | Surface roughness; standard deviation of canopy height model (Parker & Russ [43]) | |

| Canopy rugosity | Leaf area density variability of voxels; horizontal standard deviation of vertical standard deviation (Hardiman et al. [41]) | |

| Canopy porosity | Proportion of closed gap (empty) voxels within the canopy (Hardiman et al. [41]) | |

| Euphotic depth | Plot mean height difference between euphotic (high-light) and oligophotic (low-light) voxels within a column (Lefsky et al. [45], Kamoske et al. [44]) |

| Structural Metric | IRrNIR | NIRrC | %N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rumple | 0.38 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Rugosity | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.02 |

| Canopy rugosity | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.1 |

| Canopy porosity | 0.57 | 0.56 | 0.42 |

| Euphotic depth | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.04 |

| LAI 2200C | 0.44 | 0.55 * | 0.49 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sullivan, F.B.; Hastings, J.H.; Ollinger, S.V.; Ouimette, A.; Richardson, A.D.; Palace, M. Parsing the Relative Contributions of Leaf and Canopy Traits in Airborne Spectrometer Measurements. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 355. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020355

Sullivan FB, Hastings JH, Ollinger SV, Ouimette A, Richardson AD, Palace M. Parsing the Relative Contributions of Leaf and Canopy Traits in Airborne Spectrometer Measurements. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(2):355. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020355

Chicago/Turabian StyleSullivan, Franklin B., Jack H. Hastings, Scott V. Ollinger, Andrew Ouimette, Andrew D. Richardson, and Michael Palace. 2026. "Parsing the Relative Contributions of Leaf and Canopy Traits in Airborne Spectrometer Measurements" Remote Sensing 18, no. 2: 355. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020355

APA StyleSullivan, F. B., Hastings, J. H., Ollinger, S. V., Ouimette, A., Richardson, A. D., & Palace, M. (2026). Parsing the Relative Contributions of Leaf and Canopy Traits in Airborne Spectrometer Measurements. Remote Sensing, 18(2), 355. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020355