A Multi-Temporal Sentinel-2 and Machine Learning Approach for Precision Burned Area Mapping: The Sardinia Case Study

Highlights

- A locally calibrated method for mapping burned areas (BAs) in Mediterranean environments was developed using Sentinel-2 MSI time series, integrating spectral, temporal, and topographic information within Google Earth Engine.

- The model achieved a Dice Coefficient of 91.8%, significantly outperforming existing regional (EFFIS) and global (MODIS, CLMS) burned area products, especially for small and fast-recovering fires.

- The proposed approach enables accurate, high-resolution, and consistent annual burned area mapping, supporting long-term wildfire monitoring and vegetation recovery assessment.

- The workflow is transferable to other Mediterranean or fire-prone regions, offering an operational and scalable tool for environmental monitoring, land management, and climate-related fire impact studies.

Abstract

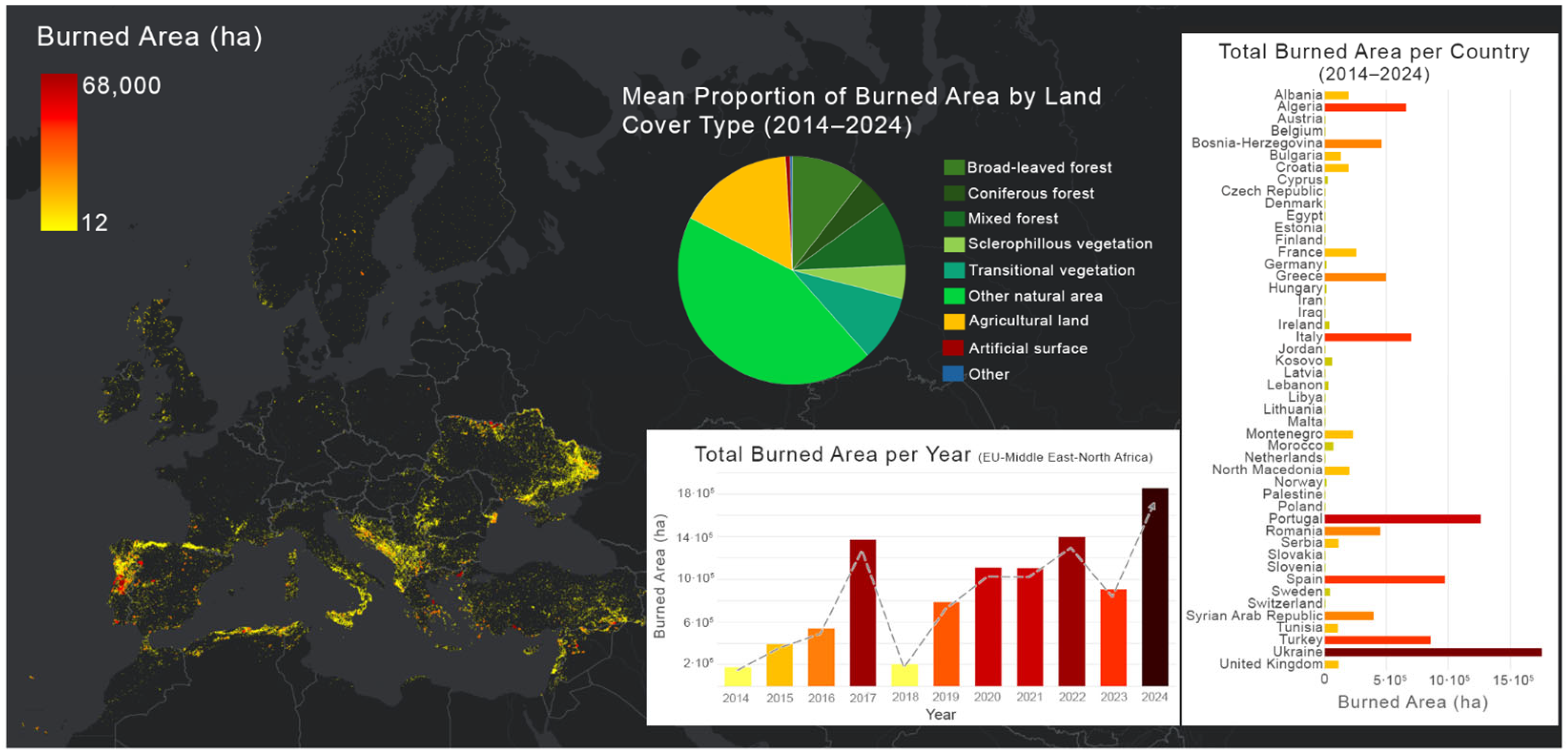

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

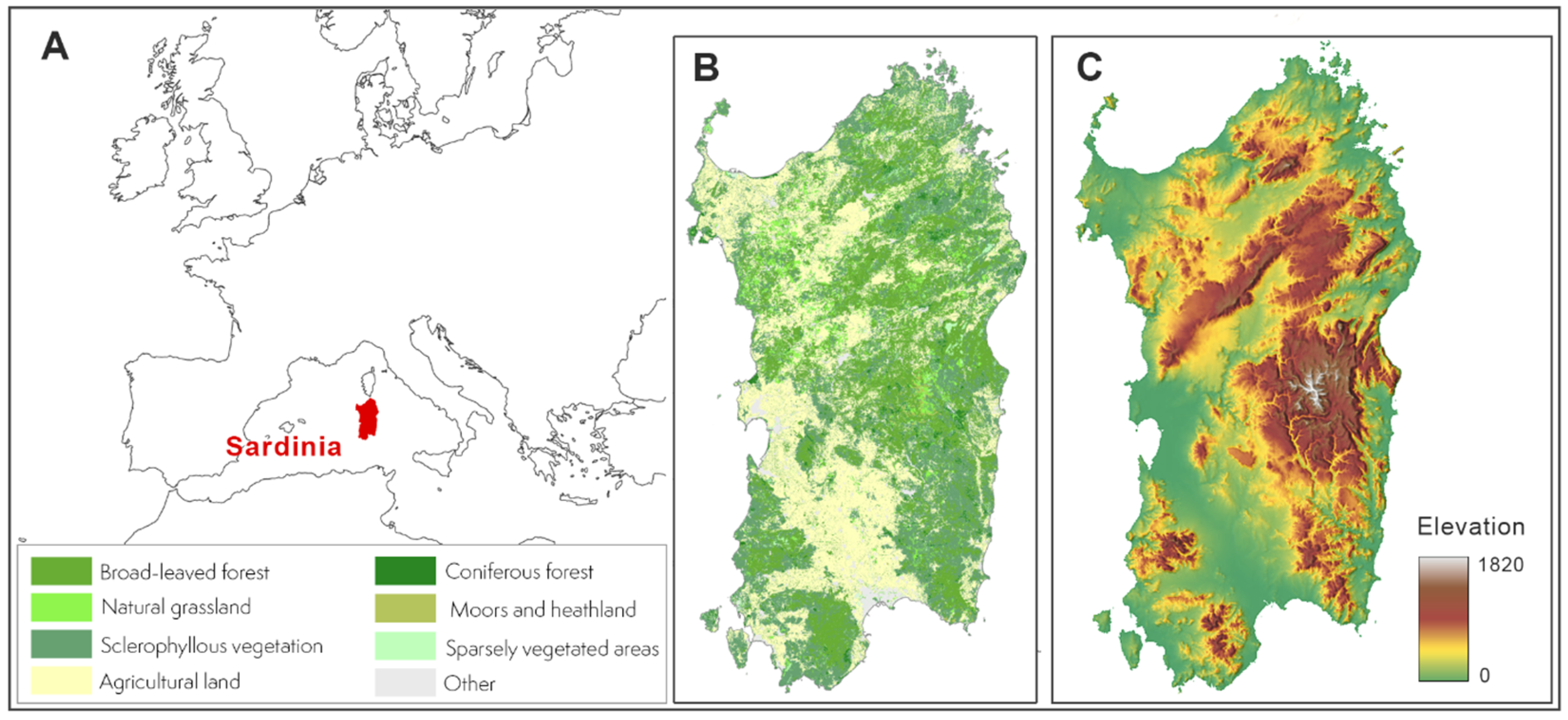

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data

2.2.1. Sentinel-2 MSI Images

2.2.2. GPS Field Measurements of Burned Areas (CFVA 2020 and CFVA 2024)

2.2.3. The Digital Terrain Model (DTM) of Sardinia

2.2.4. Land Cover Data

2.2.5. EFFIS Burnt Area Product

2.2.6. CLMS Global BA v3

2.2.7. MODIS Burned Area Monthly Global 500 m (MCD64A)

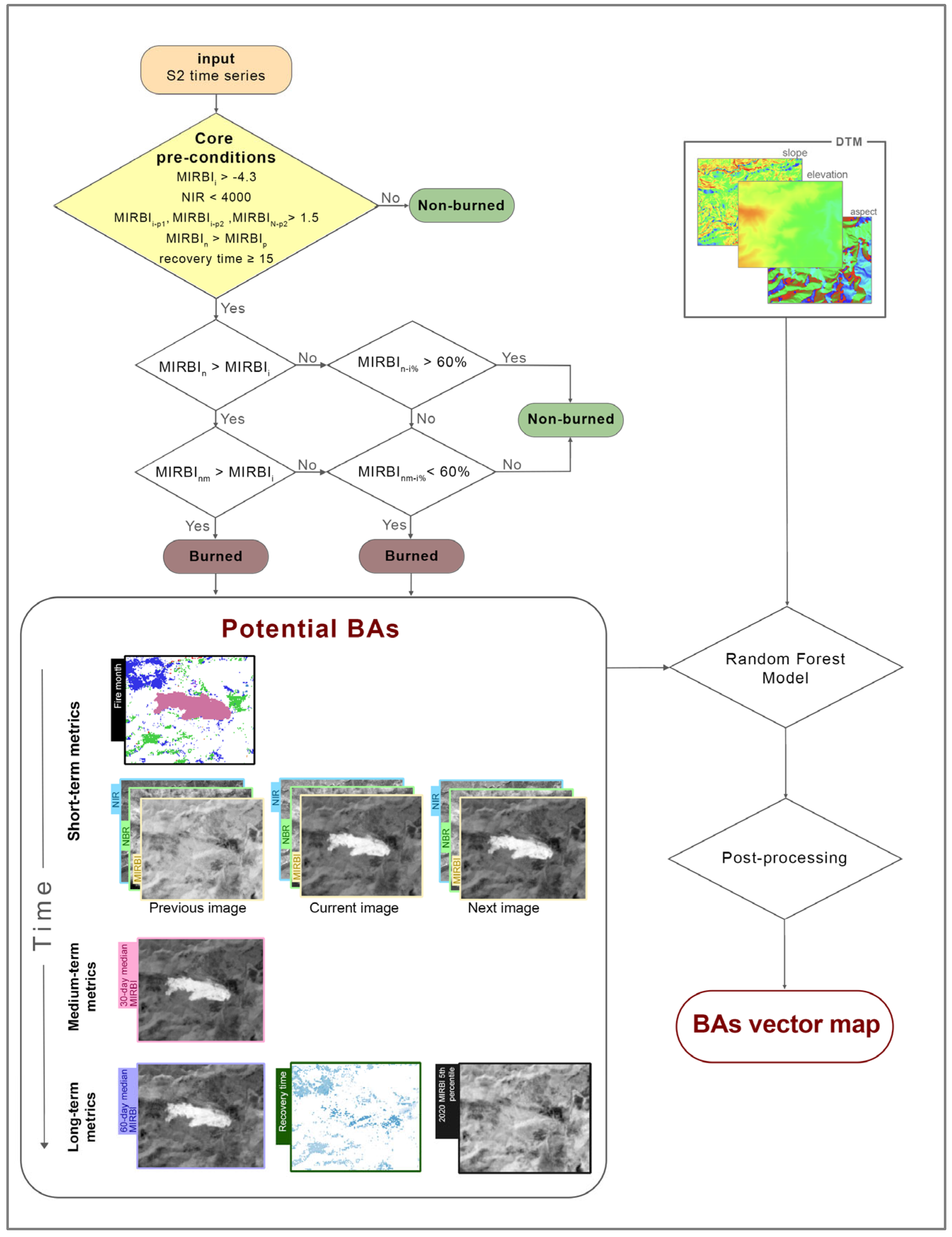

2.3. Methods

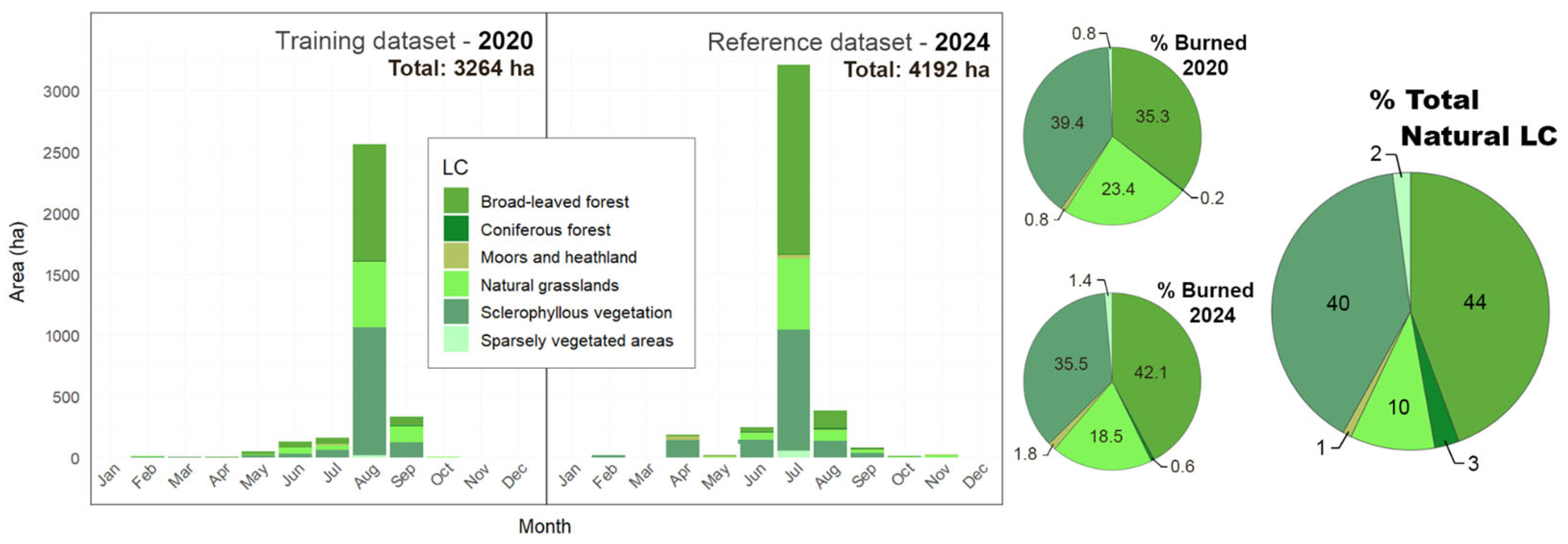

2.3.1. Training and Reference Polygons

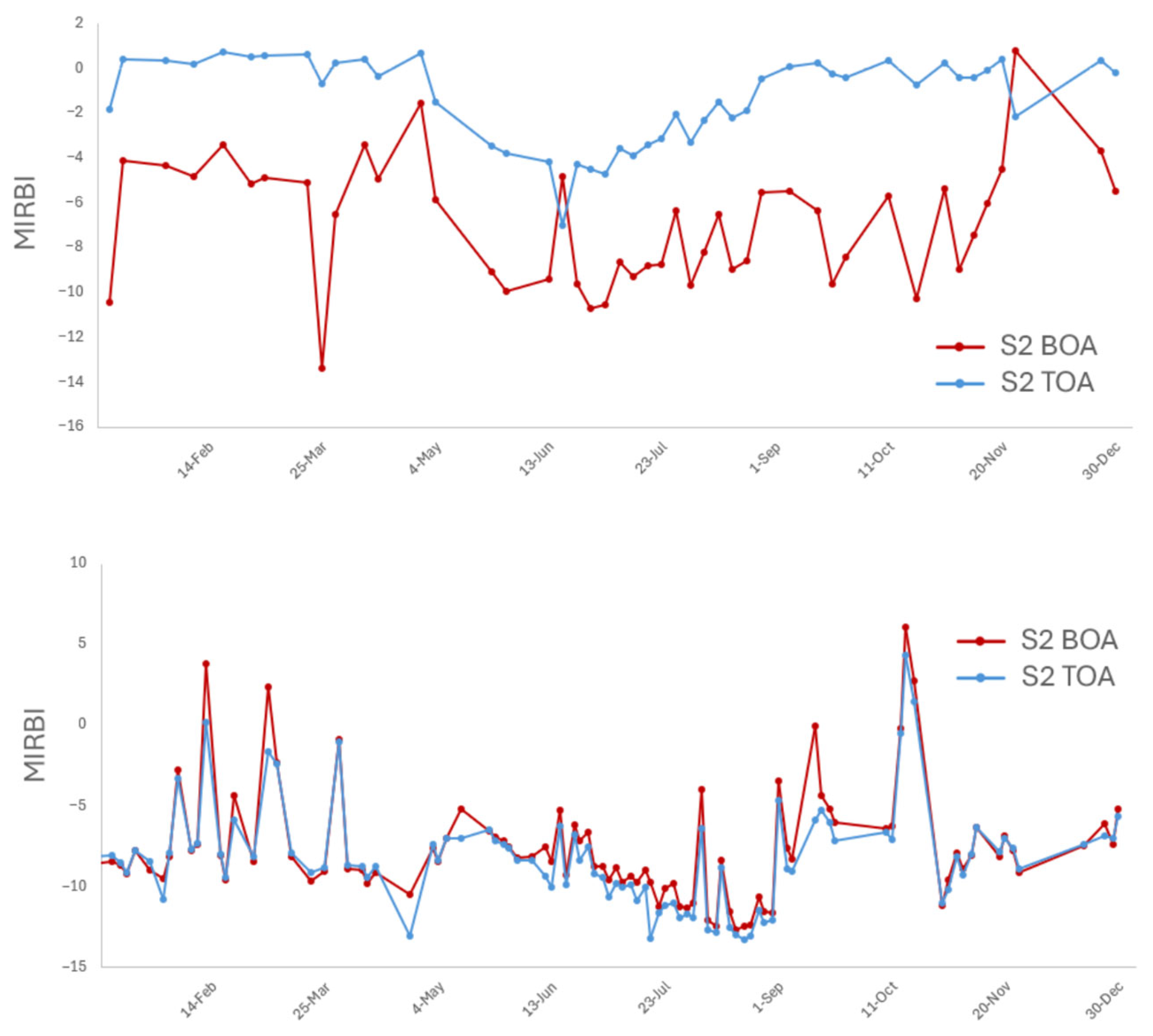

2.3.2. Evaluation of Spectral Indices

2.3.3. Detection and Delineation of BAs

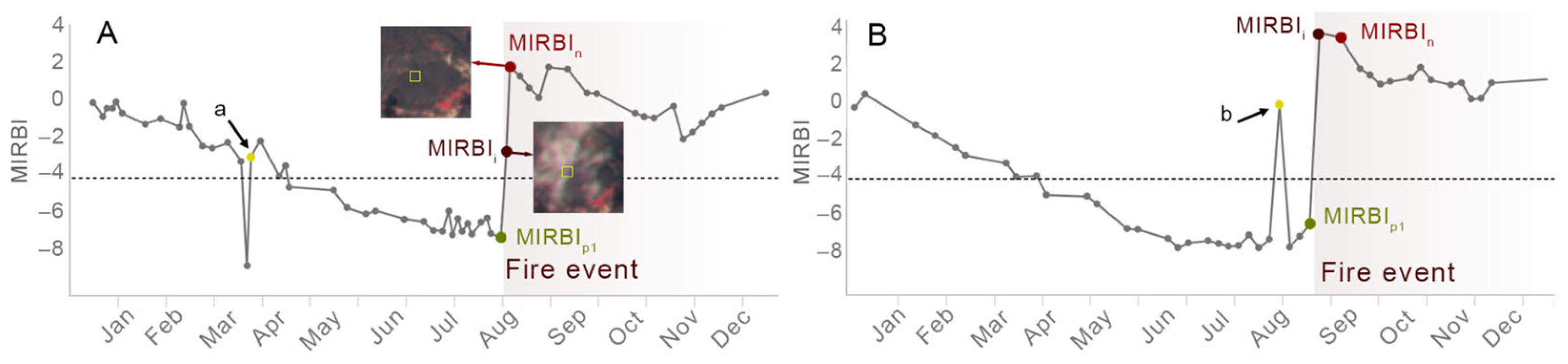

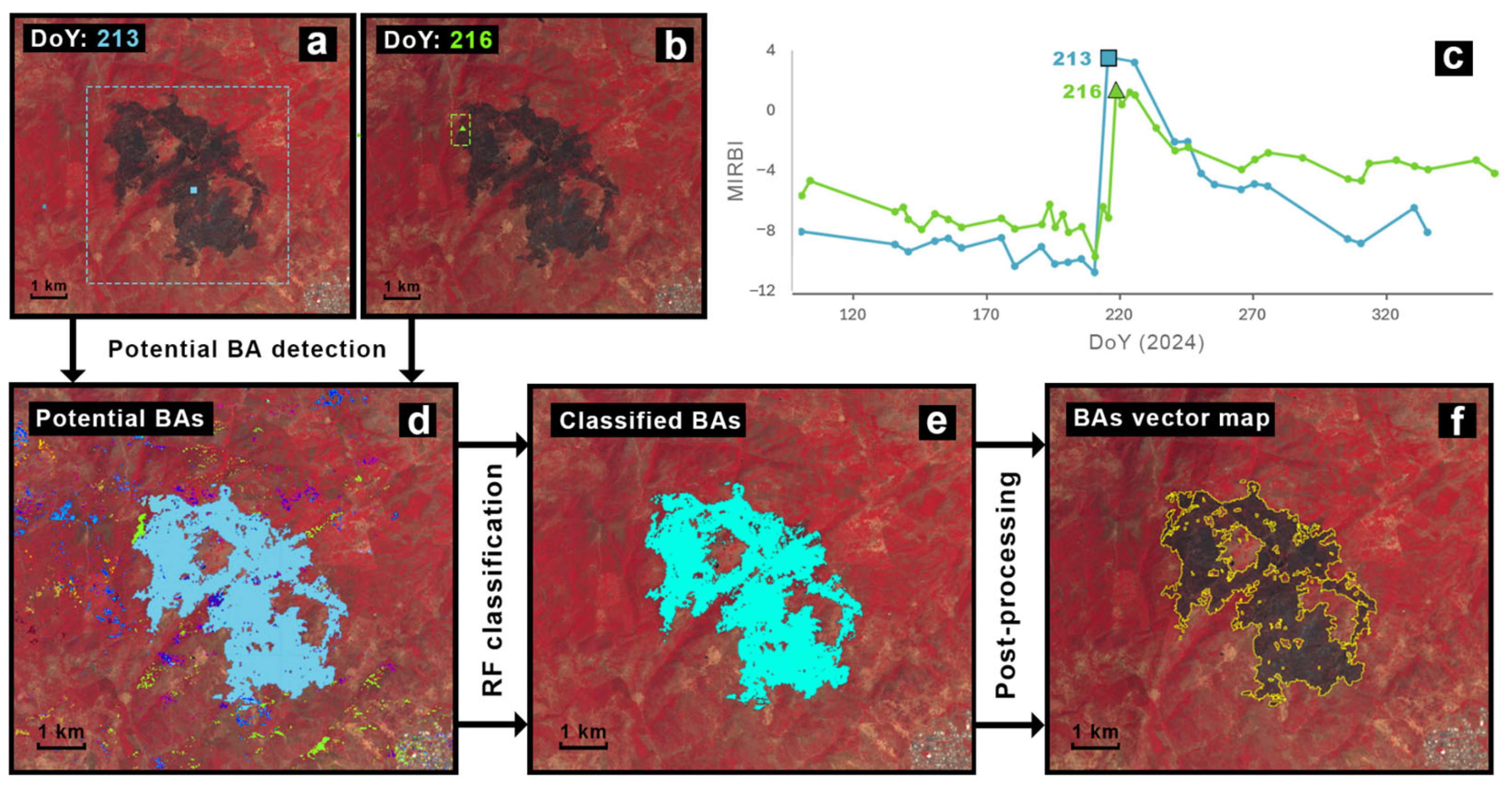

Potential BA Detection

- Condition 1, applied to detect potential burned areas, applies the optimal MIRBI threshold identified through ROC analysis to discriminate burned from unburned surfaces.

- Condition 2, which is introduced to exclude high-reflectance surfaces such as snow, can produce persistently elevated MIRBI values following abrupt spectral changes similar to those caused by fires, but typically exhibit much higher albedo and NIR reflectance ranges than burned surfaces (typically > 6000). This condition constrains NIR reflectance using a deliberately conservative, empirically defined threshold, set well above the optimal NIR threshold for detecting BA (NIR < 1722.2) derived from ROC analysis (see Appendix A, Table A1). The purpose of this higher threshold is not to detect BAs, but solely to reliably filter out high-albedo phenomena such as snow or clouds.

- Condition 3 is designed to detect abrupt increase in MIRBI that is indicative of fire event. The threshold of 1.5 was determined through ROC analysis. However, to reduce false detections caused by transient fluctuations or noise, additional temporal restrictions are imposed. Specifically, an increase of at least 1.5 must not only occur between the current and previous observation (MIRBIi−p1), but it must also be consistent when compared with the observation preceding MIRBIp1 (MIRBIi−p2), ensuring that the MIRBI rise is not related to an isolated negative peak at MIRBIp1. In addition, the increase of 1.5 must persist in the subsequent observation (MIRBIn−p2), confirming that the change is sustained over time.

- Condition 4 is introduced to confirm that the detected increase is sustained over time, by comparing the first most recent valid observation after the current processing date (MIRBIn) with the first most recent valid observation preceding it (MIRBIp). This additional precaution ensures that the spectral change is consistent with a burned surface rather than a transient fluctuation caused by noise or short-term effects.

- Condition 5, designed to avoid classifying as burned areas those surfaces where MIRBI, after an initial increase, returns to a value comparable to the pre-event level in less than 15 days. Such rapid recovery is unlikely to represent a true burned surface and is often caused by persistent cloud cover.

- 1.

- the 30-day median MIRBI (MIRBInm) remains higher than MIRBIi, a behavior which may result from residual atmospheric or surface disturbances affecting the initial detection (e.g., thin clouds, smoke, or shadows) that artificially lower MIRBIi, or from genuine post-fire processes, such as prolonged combustion or soil erosion [1,60], which further intensify the MIRBI response in the following weeks;

- 2.

- the 30-day median MIRBI does not decrease by more than 60% relative to the initial MIRBI increase observed after the fire. In the second scenario, a decrease is observed after the event (MIRBIn < MIRBIi), which represents the most common post-fire behavior; the signal is further assessed to distinguish true fire signals from noise. Specifically, two sub-scenarios are defined based on the percentage drop relative to the initial post-fire increase: if the decrease is too steep (MIRBIn−i% > 60%), the event is discarded, as it is likely associated with persistent cloud or shadow interference; conversely, if the decrease is moderate (MIRBIn−i% < 60%) and the 30-day median also remains consistent (MIRBInm−i% < 60%), the fire signal is retained. The 60% threshold for the 30-day median MIRBI decrease was selected empirically based on a series of tests where different values (from 10% to 90%, with 10% increments) were evaluated. This analysis showed that for values higher than 60%, the omission rate of burned pixels remains stable. This threshold is therefore a conservative choice, set at the point where true fire signals are maximized, and further increases would only risk including persistent cloud or shadow interference. Importantly, the threshold represents a relative measure of post-fire recovery dynamics: it assesses whether the signal decrease after the initial post-fire increase is unusually steep or moderate. Because it is based on relative changes in the time series rather than absolute MIRBI values, this approach can be reasonably applied to other regions, even with different vegetation phenology or soil backgrounds. Importantly, the threshold represents a relative measure of post-fire recovery dynamics: it assesses whether the signal decrease after the initial post-fire increase is unusually steep (likely due to persistent cloud or shadow interference) or moderate (consistent with true fire recovery). Because it is based on relative changes in the time series rather than absolute MIRBI values, this approach can be reasonably applied to other regions, even with different vegetation phenology or soil backgrounds.

BA Delineation

BA Post-Processing

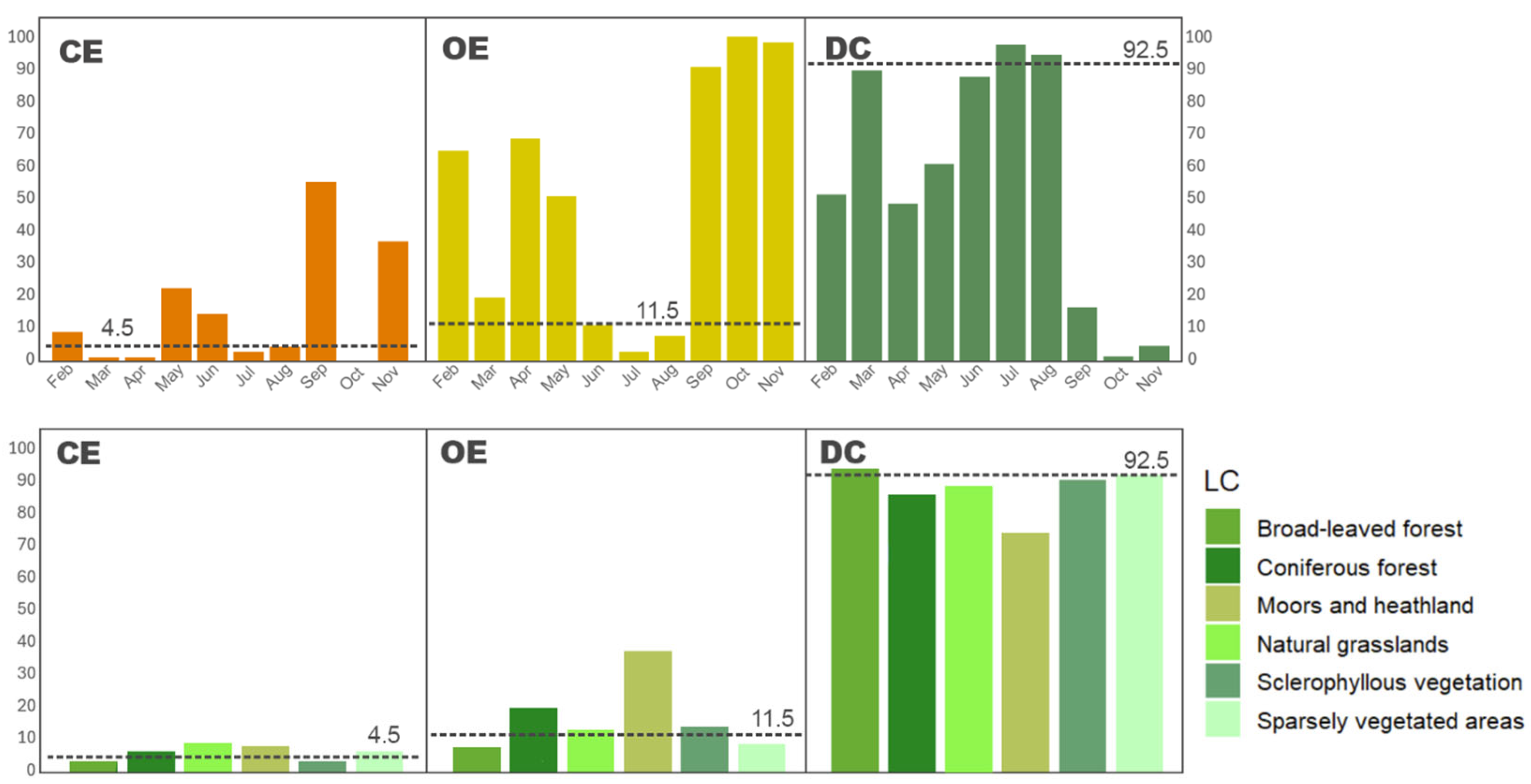

2.3.4. Validation

3. Results

3.1. Training and Reference Dataset

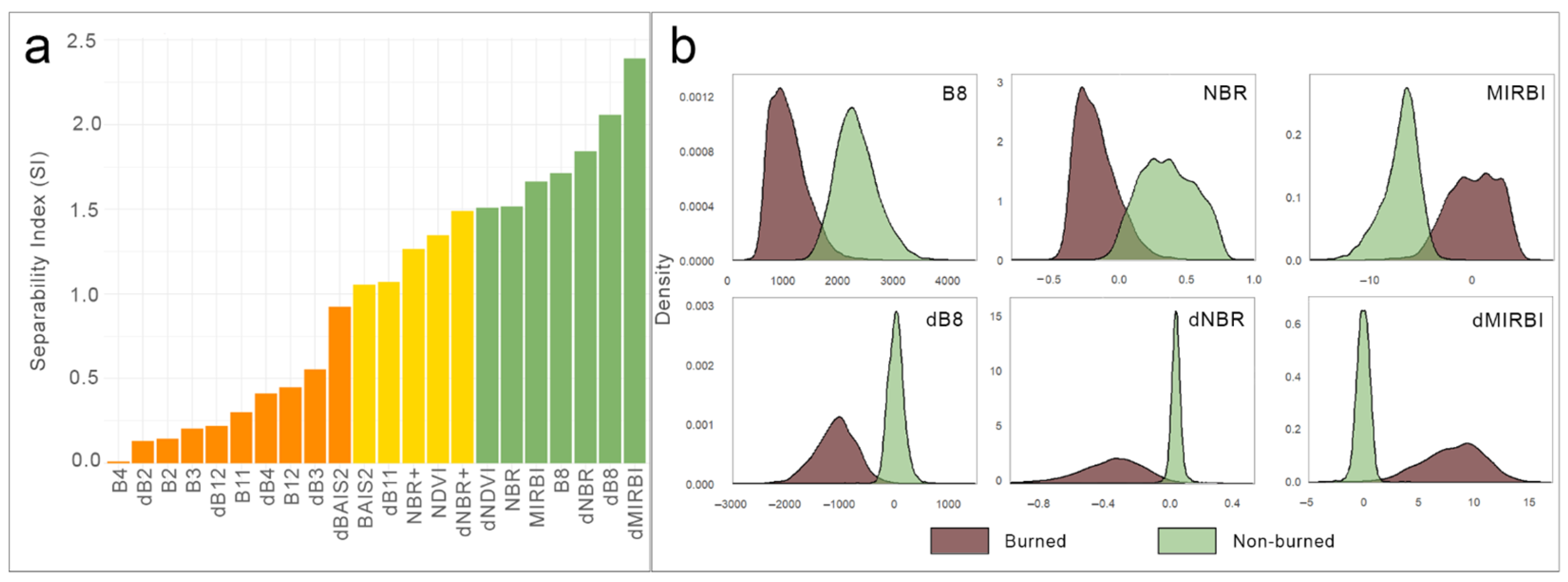

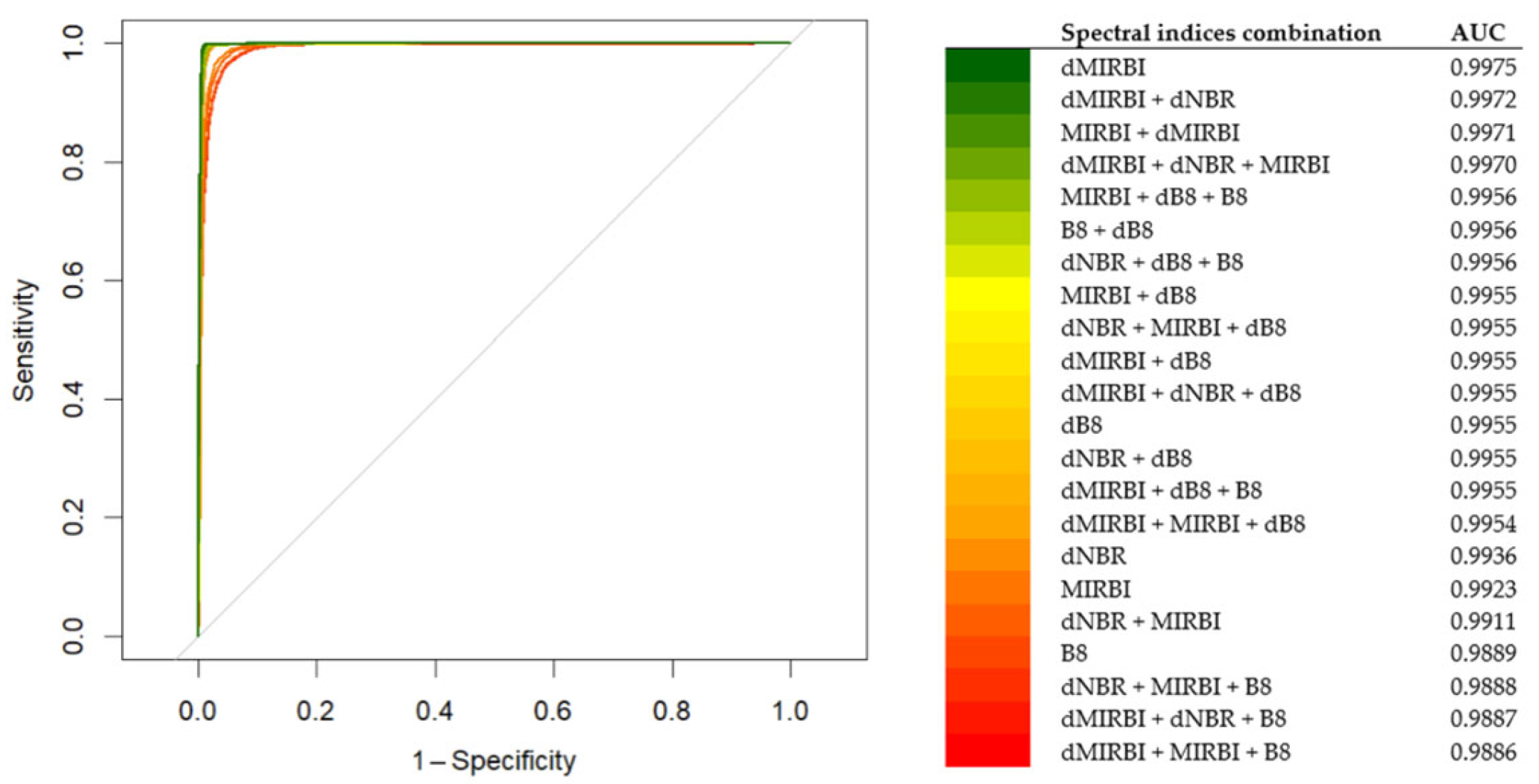

3.2. Evaluation of Spectral Indices

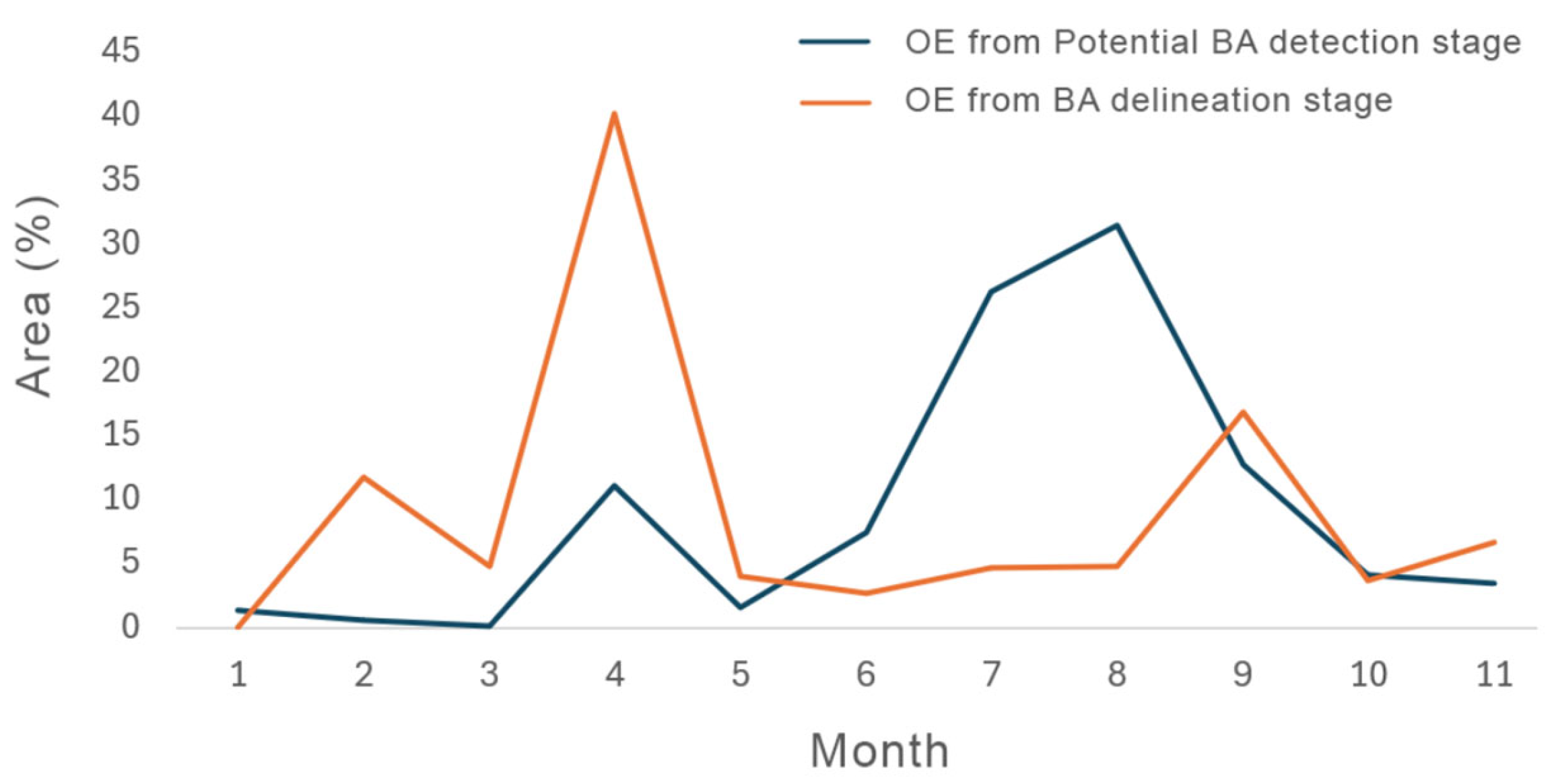

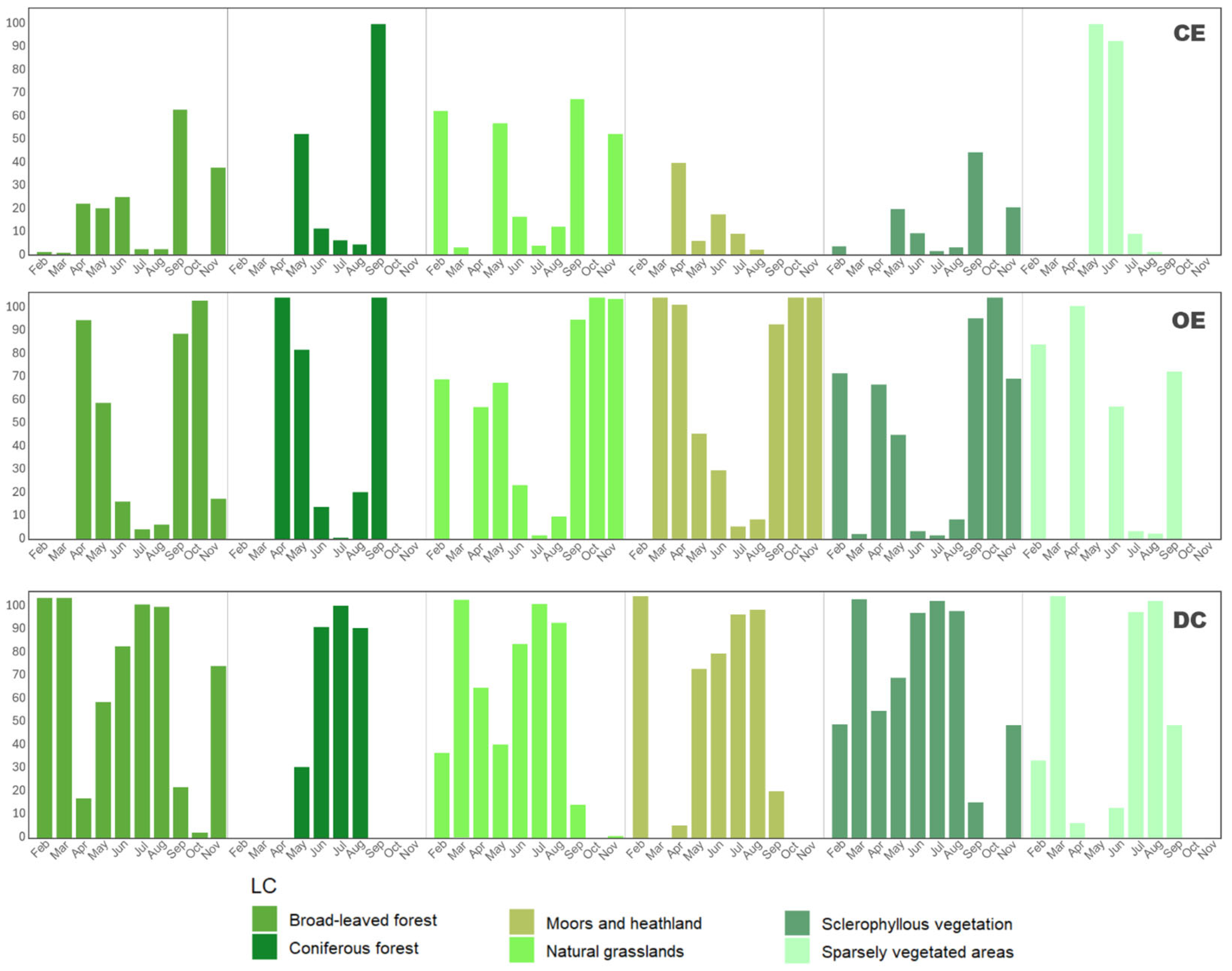

3.3. Detection and Delineation of BAs

3.4. Validation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Threshold | AUC |

|---|---|---|

| B2 | 910.75 | 0.6208963 |

| B3 | 936.25 | 0.6037115 |

| B4 | 636.75 | 0.5531063 |

| B8 | 1722.25 | 0.988931 |

| B11 | 1973.25 | 0.6488905 |

| B12 | 1194.75 | 0.7599629 |

| NBR | 0.0348599 | 0.981869 |

| MIRBI | −4.3373499 | 0.9922898 |

| NDVI | 0.2623452 | 0.9648889 |

| NBR+ | −0.4602851 | 0.9621721 |

| BAIS2 | 0.2101454 | 0.9881262 |

| dB2 | −94.75 | 0.6022082 |

| dB3 | −107.75 | 0.7974249 |

| dB4 | −142.75 | 0.7008126 |

| dB8 | −308.75 | 0.9955223 |

| dB11 | −238.75 | 0.9246589 |

| dB12 | 135.75 | 0.6065659 |

| dNBR | −0.0751243 | 0.9936156 |

| dMIRBI | 1.5934005 | 0.9974516 |

| dNDVI | −0.0340062 | 0.9795337 |

| dNBR+ | 0.0479007 | 0.9784764 |

| dBAIS2 | −0.1729811 | 0.9876758 |

References

- Pala, C.; Melis, M.T.; Pioli, L.; Sarro, R.; Loddo, S.; Cinus, S.; Brunetti, M.T. Sediment generation through thermal spalling during the 2021 montiferru planargia wildfire and its contribution to postfire debris flows. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 30918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Kolden, C.A.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Johnston, F.H.; van der Werf, G.R.; Flannigan, M. Vegetation fires in the Anthropocene. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 500–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.W.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Veraverbeke, S.; Andela, N.; Lasslop, G.; Forkel, M.; Smith, A.J.P.; Burton, C.; Betts, R.A.; van der Werf, G.R.; et al. Global and Regional Trends and Drivers of Fire Under Climate Change. Rev. Geophys. 2022, 60, e2020RG000726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, D.I.; Burton, C.; Di Giuseppe, F.; Jones, M.W.; Barbosa, M.L.F.; Brambleby, E.; McNorton, J.R.; Liu, Z.; Bradley, A.S.I.; Blackford, K.; et al. State of Wildfires 2024–2025. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 5377–5488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, C.X.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Ellis, T.M.; Williamson, G.J.; Bowman, D.M.J.S. Wildfires will intensify in the wildland-urban interface under near-term warming. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salis, M.; Arca, B.; Alcasena, F.; Arianoutsou, M.; Bacciu, V.; Duce, P.; Duguy, B.; Koutsias, N.; Mallinis, G.; Mitsopoulos, I.; et al. Predicting wildfire spread and behaviour in Mediterranean landscapes. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2016, 25, 1015–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viedma, O.; Moity, N.; Moreno, J.M. Changes in landscape fire-hazard during the second half of the 20th century: Agriculture abandonment and the changing role of driving factors. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2015, 207, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, F.; Ascoli, D.; Safford, H.; Adams, M.A.; Moreno, J.M.; Pereira, J.C.; Catry, F.X.; Armesto, J.; Bond, W.J.; González, M.E.; et al. Wildfire management in Mediterranean-type regions: Paradigm change needed. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 011001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Miguel-Ayanz, J.; Durrant, T.; Boca, R.; Maianti, P.; Liberta, G.; Oom, D.; Branco, A.; de Rigo, D.; Suarez Moreno, M.; Ferrari, D.; et al. Advance Report on Forest Fires in Europe, Middle East and North Africa 2024; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock, H.C.; Hoffer, R.M. Mapping a recent forest fire with ERTS-1 MSS data. In Proceedings of the Remote Sensing of Earth Resources, Volume 3—Third Conference on Earth Resources Observation and Information Analysis System, Tullahoma, TN, USA, 25–27 March 1974; pp. 449–461. [Google Scholar]

- French, N.H.F.; Kasischke, E.S.; Hall, R.J.; Murphy, K.A.; Verbyla, D.L.; Hoy, E.E.; Allen, J.L. Using Landsat data to assess fire and burn severity in the North American boreal forest region: An overview and summary of results. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2008, 17, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuvieco, E.; Mouillot, F.; van der Werf, G.R.; San Miguel, J.; Tanase, M.; Koutsias, N.; García, M.; Yebra, M.; Padilla, M.; Gitas, I.; et al. Historical background and current developments for mapping burned area from satellite Earth observation. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 225, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.M.; He, Y.; Moore, G.W.K. Trends and applications in wildfire burned area mapping: Remote sensing data, cloud geoprocessing platforms, and emerging algorithms. Geomatica 2024, 76, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuvieco, E.; Lizundia-Loiola, J.; Pettinari, M.L.; Ramo, R.; Padilla, M.; Tansey, K.; Mouillot, F.; Laurent, P.; Storm, T.; Heil, A.; et al. Generation and analysis of a new global burned area product based on MODIS 250 m reflectance bands and thermal anomalies. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2018, 10, 2015–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avetisyan, D.; Velizarova, E.; Filchev, L. Post-Fire Forest Vegetation State Monitoring through Satellite Remote Sensing and In Situ Data. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaveau, D.L.A.; Descals, A.; Salim, M.A.; Sheil, D.; Sloan, S. Refined burned-area mapping protocol using Sentinel-2 data increases estimate of 2019 Indonesian burning. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 5353–5368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.J.L.; Caselles, V. Mapping burns and natural reforestation using thematic Mapper data. Geocarto Int. 1991, 6, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.M.N.; Cadima, J.F.C.L.; Pereira, J.M.C.; Grégoire, J.-M. Assessing the feasibility of a global model for multi-temporal burned area mapping using SPOT-VEGETATION data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2004, 25, 4889–4913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, C.H.; Benson, N.C. The normalized burn ratio, a Landsat TM radiometric index of burn severity incorporating multi-temporal differencing. In US Geological Survey; Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center: Bozeman, MT, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Trigg, S.; Flasse, S. An evaluation of different bi-spectral spaces for discriminating burned shrub-savannah. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2001, 22, 2641–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, C.C.; Olthoff, A.E.; Hernández-Trejo, H.; Rullán-Silva, C.D. Evaluating the best spectral indices for burned areas in the tropical Pantanos de Centla Biosphere Reserve, Southeastern Mexico. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2022, 25, 100664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipponi, F. BAIS2: Burned Area Index for Sentinel-2. Proceedings 2018, 2, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaras, E.; Costantino, D.; Guastaferro, F.; Parente, C.; Pepe, M. Normalized Burn Ratio Plus (NBR+): A New Index for Sentinel-2 Imagery. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuvieco, E.; Congalton, R.G. Mapping and inventory of forest fires from digital processing of tm data. Geocarto Int. 1988, 3, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschetti, M.; Stroppiana, D.; Brivio, P.A. Mapping Burned Areas in a Mediterranean Environment Using Soft Integration of Spectral Indices from High-Resolution Satellite Images. Earth Interact. 2010, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giglio, L.; Boschetti, L.; Roy, D.P.; Humber, M.L.; Justice, C.O. The Collection 6 MODIS burned area mapping algorithm and product. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 217, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Liu, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhao, W.; Wu, H.; Xu, W. Burned area detection and mapping using time series Sentinel-2 multispectral images. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 296, 113753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veraverbeke, S.; Lhermitte, S.; Verstraeten, W.W.; Goossens, R. Evaluation of pre/post-fire differenced spectral indices for assessing burn severity in a Mediterranean environment with Landsat Thematic Mapper. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2011, 32, 3521–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, M.; Stehman, S.V.; Ramo, R.; Corti, D.; Hantson, S.; Oliva, P.; Alonso-Canas, I.; Bradley, A.V.; Tansey, K.; Mota, B.; et al. Comparing the accuracies of remote sensing global burned area products using stratified random sampling and estimation. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 160, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipponi, F. Exploitation of Sentinel-2 Time Series to Map Burned Areas at the National Level: A Case Study on the 2017 Italy Wildfires. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giglio, L.; Boschetti, L.; Roy, D.; Hoffmann, A.A.; Humber, M.; Hall, J.V. Collection 6.1 MODIS Burned Area Product User’s Guide Version 1.0; NASA EOSDIS Land Processes DAAC: Sioux Falls, SD, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla, M.; Van Der Goten, R.; Jacobs, T. Copernicus Global Land Operations “Vegetation and Energy”, “CGLOPS-1” Product User Manual, Burned Area Version 3.1; Zenodo: Geneve, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Galizia, L.F.; Curt, T.; Barbero, R.; Rodrigues, M. Assessing the accuracy of remotely sensed fire datasets across the southwestern Mediterranean Basin. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 21, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, G.; Silva, J.M.N.; Modica, G. Regional-scale burned area mapping in Mediterranean regions based on the multitemporal composite integration of Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data. Gisci. Remote Sens. 2022, 59, 1678–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salis, M.; Ager, A.A.; Alcasena, F.J.; Arca, B.; Finney, M.A.; Pellizzaro, G.; Spano, D. Analyzing seasonal patterns of wildfire exposure factors in Sardinia, Italy. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015, 187, 4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salis, M.; Arca, B.; Del Giudice, L.; Palaiologou, P.; Alcasena-Urdiroz, F.; Ager, A.; Fiori, M.; Pellizzaro, G.; Scarpa, C.; Schirru, M.; et al. Application of simulation modeling for wildfire exposure and transmission assessment in Sardinia, Italy. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 58, 102189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drusch, M.; Del Bello, U.; Carlier, S.; Colin, O.; Fernandez, V.; Gascon, F.; Hoersch, B.; Isola, C.; Laberinti, P.; Martimort, P.; et al. Sentinel-2: ESA’s Optical High-Resolution Mission for GMES Operational Services. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 120, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main-Knorn, M.; Pflug, B.; Louis, J.; Debaecker, V.; Müller-Wilm, U.; Gascon, F. Sen2Cor for Sentinel-2. In Image and Signal Processing for Remote Sensing XXIII; Bruzzone, L., Bovolo, F., Benediktsson, J.A., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2017; p. 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roteta, E.; Bastarrika, A.; Franquesa, M.; Chuvieco, E. Landsat and Sentinel-2 Based Burned Area Mapping Tools in Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, J.; Devignot, O.; Pessiot, L. S2 MPC—Level-2A Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document; European Space Agency: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zekoll, V.; Main-Knorn, M.; Louis, J.; Frantz, D.; Richter, R.; Pflug, B. Comparison of masking algorithms for sentinel-2 imagery. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CFVA—Perimetri dei Soprassuoli Percorsi dal Fuoco. 2024. Available online: https://webgis2.regione.sardegna.it/geonetwork/srv/ita/catalog.search#/metadata/R_SARDEG:70f50b3a-6dbd-40cf-b1c9-a8c72b764ce6 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Sardegna Geoportale—DTM 10 m. 2025. Available online: https://webgis2.regione.sardegna.it/geonetwork/srv/ita/catalog.search#/metadata/R_SARDEG:JDCBN (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Collu, C.; Dessì, F.; Simonetti, D.; Lasio, P.; Botti, P.; Melis, M.T. On the application of remote sensing time series analysis for land cover mapping: Spectral indices for crops classification. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote. Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022, XLIII-B3-2, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Associazione Italiana di Telerilevamento (AIT) (Ed.) Open Source Technologies for Mapping: Impact Toolbox and the Land Cover Map of Sardinia. In Earth Observation: Current Challenges and Opportunities for Environmental Monitoring; AIT Series “Trends in Earth Observation”; Volume 3, Associazione Italiana di Telerilevamento (AIT): Firenze, Italy, 2024; pp. 70–73. ISBN 978-88-944687-2-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudu, P.L.; Fiori, M.; Peana, I.; Delitala, A. Rapporto Meteo e Clima 2024; Regione Autonoma della Sardegna, Assessorato della Difesa dell’Ambiente: Cagliari, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Del Pilar, M.; Laabal, M.; Sallnaro, E.C. Cartografía de Grandes Incendios Forestales en la Península Ibérica a Partir de Imágenes Noaa-avhrr; Universidad de Alcalá de Henares: Madrid, Spain, 1998; Volume 7, pp. 109–128. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, N.; Key, C.H. Landscape Assessment: Ground Measure of Severity, the Composite Burn Index; and Remote Sensing of Severity, the Normalized Burn Ratio; USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sall, B.; Jenkins, M.W.; Pushnik, J. Retrospective analysis of two northern California wild-land fires via Landsat five satellite imagery and Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI). Open J. Ecol. 2013, 3, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisanty, D.; Ramadhan, M.F.; Angriani, P.; Muhaimin, M.; Saputra, A.N.; Hastuti, K.P.; Rosadi, D. Utilizing Sentinel-2 Data for Mapping Burned Areas in Banjarbaru Wetlands, South Kalimantan Province. Int. J. For. Res. 2022, 2022, 7936392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotakidis, V.; Chrysafis, I.; Mallinis, G.; Koutsias, N. Continuous burned area monitoring using bi-temporal spectral index time series analysis. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 125, 103547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskouni, F.H.; Seydi, S.T. Forest Burned Area Mapping Using Bi-Temporal Sentinel-2 Imagery Based on a Convolutional Neural Network: Case Study in Golestan Forest. Eng. Proc. 2021, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veraverbeke, S.; Harris, S.; Hook, S. Evaluating spectral indices for burned area discrimination using MODIS/ASTER (MASTER) airborne simulator data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, 115, 2702–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, Y.J.; Remer, L.A. Detection of Forests Using Mid-IR Reflectance: An Application for Aerosol Studies. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote. Sens. 1994, 32, 672–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiraglia, D.; Filipponi, F.; Mandrone, S.; Tornato, A.; Taramelli, A. Agreement index for burned area mapping: Integration of multiple spectral indices using Sentinel-2 satellite images. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, T. An introduction to ROC analysis. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2006, 27, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobrino, J.A. Methodology for burned areas delimitation and fire severity assessment using Sentinel-2 data. A case study of forest fires occurred in Spain between 2018 and 2023. Recent Adv. Remote Sens. 2024, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinho Barbosa, P.; Miguel, J.; Pereira, C.; Grégoire, J.-M. Compositing Criteria for Burned Area Assessment Using Multitemporal Low Resolution Satellite Data; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efthimiou, N.; Psomiadis, E.; Panagos, P. Fire severity and soil erosion susceptibility mapping using multi-temporal Earth Observation data: The case of Mati fatal wildfire in Eastern Attica, Greece. Catena 2020, 187, 104320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Me, J.; Segarra, D.; Garcia-Hare, J. Modeling Rates of Ecosystem Recovery after Fires by Using Landsat TM Data; Elsevier Science Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1997; Volume 61. [Google Scholar]

- Morisette, J.T.; Baret, F.; Liang, S. Special Issue on Global Land Product Validation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2006, 44, 1695–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschetti, L.; Roy, D.P.; Justice, C.O. International Global Burned Area Satellite Product Validation Protocol Part I—Production and Standardization of Validation Reference Data (to be Followed by Part II—Accuracy Reporting); Committee on Earth Observation Satellites: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pulvirenti, L.; Squicciarino, G.; Negro, D.; Puca, S. Object-Based Validation of a Sentinel-2 Burned Area Product Using Ground-Based Burn Polygons. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 9154–9163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dice, L.R. Measures of the Amount of Ecologic Association Between Species. Ecology 1945, 26, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschetti, L.; Roy, D.P.; Giglio, L.; Huang, H.; Zubkova, M.; Humber, M.L. Global validation of the collection 6 MODIS burned area product. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 235, 111490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, M.; Stehman, S.; Litago, J.; Chuvieco, E. Assessing the Temporal Stability of the Accuracy of a Time Series of Burned Area Products. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 2050–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarley, T.R.; Smith, A.M.S.; Kolden, C.A.; Kreitler, J. Evaluating the Mid-Infrared Bi-spectral Index for improved assessment of low-severity fire effects in a conifer forest. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2018, 27, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon Kongo, L. Performance of dNDVI, dNBR and dMIRBI spectral indices in burnt areas detection Case study of Moyowosi game reserve, Kigoma, Tanzania. Afr. J. Land. Policy Geospat. Sci. 2025, 8, 2657–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudak, A.T.; Morgan, P.; Bobbitt, M.J.; Smith, A.M.S.; Lewis, S.A.; Lentile, L.B.; Robichaud, P.R.; Clark, J.T.; McKinley, R.A. The Relationship of Multispectral Satellite Imagery to Immediate Fire Effects. Fire Ecol. 2007, 3, 64–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Wu, J. An Assessment of the Suitability of Sentinel-2 Data for Identifying Burn Severity in Areas of Low Vegetation. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2022, 50, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepers, L.; Haest, B.; Veraverbeke, S.; Spanhove, T.; Vanden Borre, J.; Goossens, R. Burned Area Detection and Burn Severity Assessment of a Heathland Fire in Belgium Using Airborne Imaging Spectroscopy (APEX). Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 1803–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawbaker, T.J.; Vanderhoof, M.K.; Beal, Y.-J.; Takacs, J.D.; Schmidt, G.L.; Falgout, J.T.; Williams, B.; Fairaux, N.M.; Caldwell, M.K.; Picotte, J.J.; et al. Mapping burned areas using dense time-series of Landsat data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 198, 504–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, G.; Jin, B.; Leung, H. Multispectral Image Super-Resolution Burned-Area Mapping Based on Space-Temperature Information. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.P.; Boschetti, L.; Justice, C.O.; Ju, J. The collection 5 MODIS burned area product—Global evaluation by comparison with the MODIS active fire product. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 3690–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giglio, L.; Schroeder, W.; Justice, C.O. The collection 6 MODIS active fire detection algorithm and fire products. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 178, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Spectral Index | Formula | Sentinel-2 MSI Bands |

|---|---|---|

| NDVI | NIR (B8) RED (B4) | |

| NBR | NIR (B8) SWIR2 (B12) | |

| MIRBI | SWIR1 (B11) SWIR2 (B12) | |

| NBR+ | Red Edge 4 (RE4) SWIR1 (B11) SWIR2 (B12) | |

| BAIS2 | RED (B4) RE2—Red Edge 2 (B6) RE3—Red Edge 3 (B7) RE4—Red Edge 4 (B8A) SWIR2 (B12) |

| Metric Name | Formula | Description |

|---|---|---|

| MIRBIi | - | MIRBI value at the current processing date. |

| MIRBIp1 | - | MIRBI value corresponding to the first most recent valid (i.e., non-null) observation preceding the current processing date. |

| MIRBIp2 | - | MIRBI value corresponding to the first most recent valid (i.e., non-null) observation preceding MIRBIp1, used as control to verify the robustness of MIRBIp1 and ensure it does not represent an isolated negative peak. |

| MIRBIn | - | MIRBI value corresponding to the first most recent valid (i.e., non-null) observation after the current processing date. |

| MIRBInm | - | Median MIRBI calculated from all images acquired within 30 days after the current processing date, set to null if there are less than two valid observations in the following month, to ensure it remains a representative measure of the medium-term period, especially in cloudy periods. |

| MIRBIi−p1 | MIRBIi − MIRBIp1 | Difference between the current and preceding MIRBI value. |

| MIRBIn−p2 | MIRBIn − MIRBIp2 | Difference between the subsequent MIRBI value after the current processing date and MIRBIp2. |

| MIRBIi−p2 | MIRBIi − MIRBIp2 | Difference between the current and MIRBIp2. |

| MIRBIn−i% | Absolute percentage ratio between the difference observed after the current processing date and the change detected between the current and preceding dates, helps assess the short-term stability of the spectral signal. | |

| MIRBInm−i% | Absolute percentage ratio between the difference in the 30-day median MIRBI after the processing date and the current MIRBI, normalized by the difference between current and preceding MIRBI value; used to assess the persistence of the MIRBI signal in the medium term. | |

| Recovery time | Δdays (MIRBIn < MIRBIp + 0.5) | Number of days elapsed between the current processing date and the first subsequent date when MIRBI drops below a threshold of MIRBIp + 0.5, indicating a return to a spectral magnitude comparable to pre-fire conditions. |

| Condition 1 | |

| Condition 2 | |

| Condition 3 | |

| Condition 4 | |

| Condition 5 |

| Validation Metric | Formula |

|---|---|

| Commission Error (CE) | |

| Omission Error (OE) | |

| Dice Coefficient (DC) |

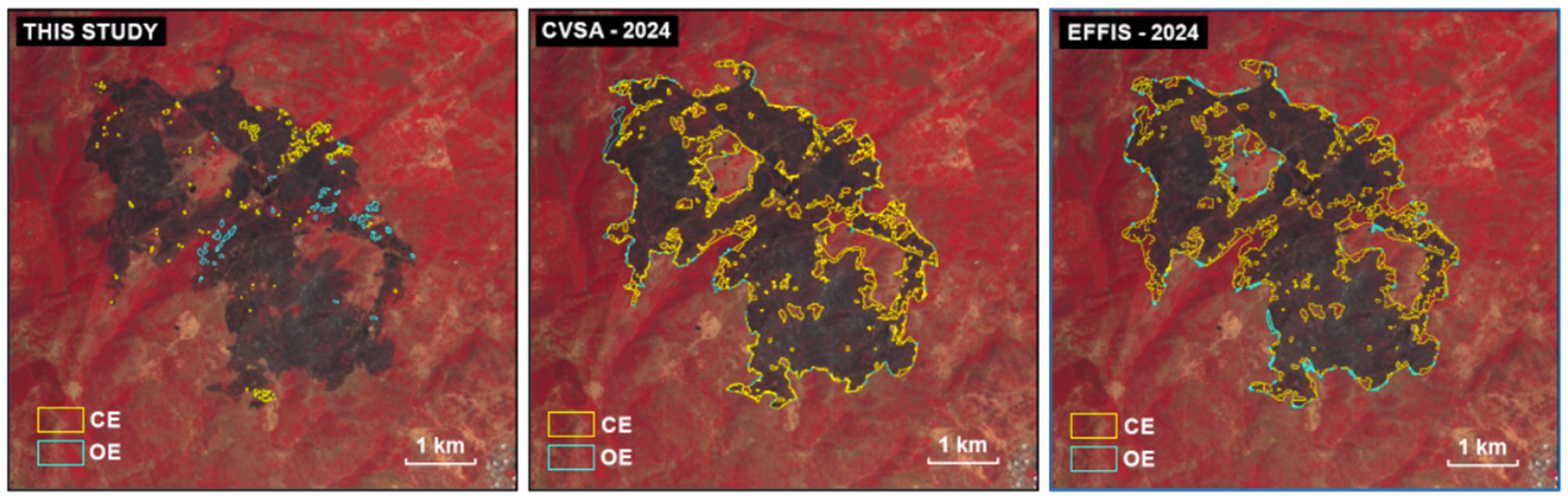

| Product | Spatial Resolution | CE (%) | OE (%) | DC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| This study | high (MMU = 1600 m2) | 4.5 | 11.5 | 91.8 |

| CFVA 2024 | high (GPS measurement) | 16.9 | 4.9 | 88.7 |

| EFFIS 2024 | high (20 m) | 17.3 | 22.8 | 79.9 |

| CLMS global BA v3 | medium-coarse (300 m) | 31.1 | 49.0 | 58.6 |

| MCD64A1 | coarse (500 m) | 52.0 | 78.4 | 29.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Collu, C.; Simonetti, D.; Dessì, F.; Casu, M.; Pala, C.; Melis, M.T. A Multi-Temporal Sentinel-2 and Machine Learning Approach for Precision Burned Area Mapping: The Sardinia Case Study. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020267

Collu C, Simonetti D, Dessì F, Casu M, Pala C, Melis MT. A Multi-Temporal Sentinel-2 and Machine Learning Approach for Precision Burned Area Mapping: The Sardinia Case Study. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(2):267. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020267

Chicago/Turabian StyleCollu, Claudia, Dario Simonetti, Francesco Dessì, Marco Casu, Costantino Pala, and Maria Teresa Melis. 2026. "A Multi-Temporal Sentinel-2 and Machine Learning Approach for Precision Burned Area Mapping: The Sardinia Case Study" Remote Sensing 18, no. 2: 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020267

APA StyleCollu, C., Simonetti, D., Dessì, F., Casu, M., Pala, C., & Melis, M. T. (2026). A Multi-Temporal Sentinel-2 and Machine Learning Approach for Precision Burned Area Mapping: The Sardinia Case Study. Remote Sensing, 18(2), 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020267