Estimating Soil Moisture Using Multimodal Remote Sensing and Transfer Optimization Techniques

Highlights

- A multimodal fusion framework integrating SAR, optical, topographic, and meteorological data achieved high-precision soil moisture estimation ( = 0.8956), significantly outperforming single-modality methods.

- An intermediate fine-tuning strategy applied to a large dataset (10,571 images and 3772 samples) substantially enhanced the model’s generalization and transferability across diverse agro-ecological zones.

- The framework enables the generation of reliable, field-scale soil moisture maps, providing a practical tool for precision irrigation and site-specific water management to enhance drought resilience.

- This approach offers a scalable and robust solution for operational soil moisture monitoring in heterogeneous landscapes, supporting sustainable water resource management from farm to regional scales.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Datasets

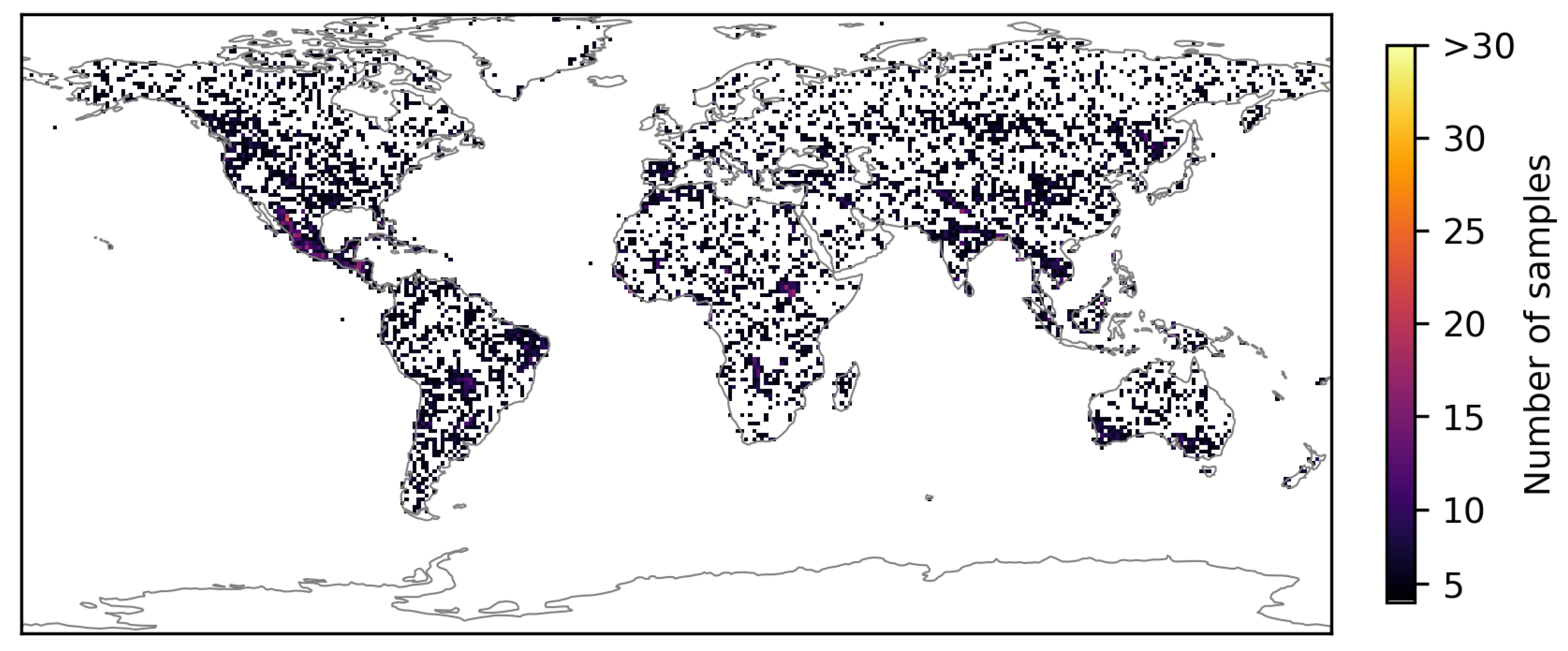

2.1.1. SSM from a Large-Scale Dataset

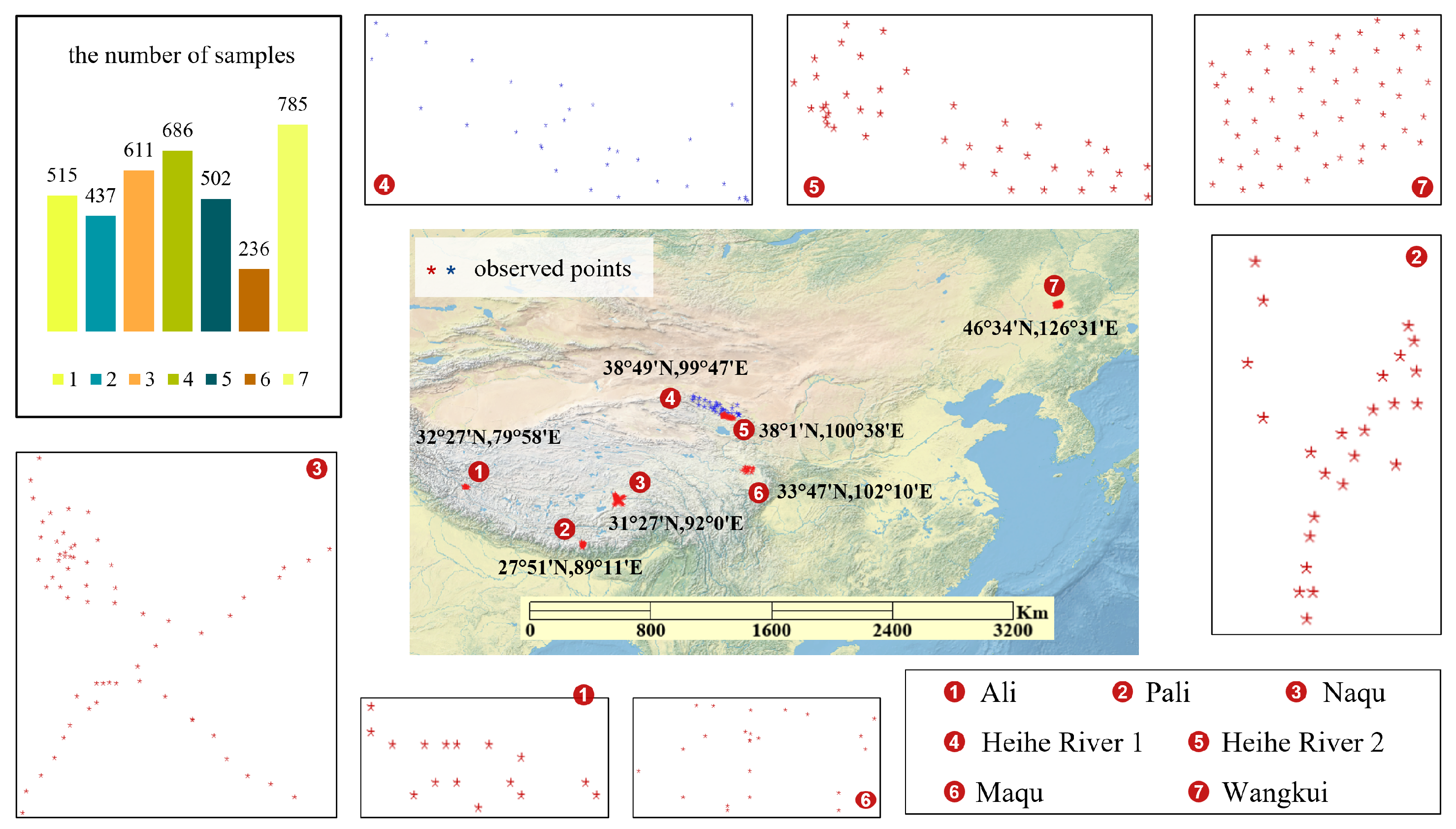

2.1.2. SSM from a Small-Scale Dataset

2.2. Data Processing

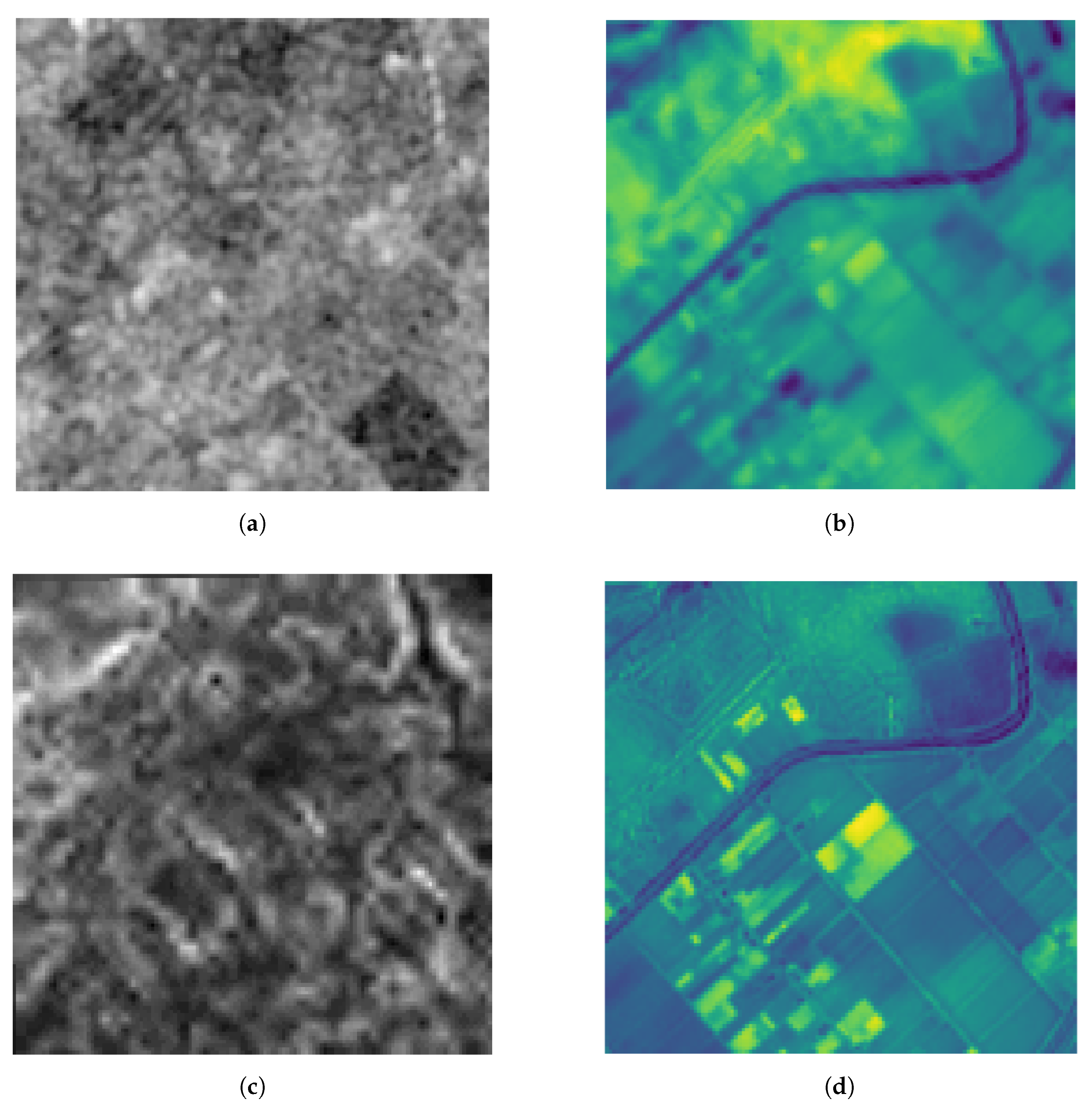

- Sentinel-1 served as the reference dataset, setting the standard for observation dates, spatial resolution and coordinate reference system. All other data sources were aligned to match this baseline. Sentinel-1 imagery is acquired in ascending and descending orbits, with each viewing direction capturing two polarization channels, resulting in four bands per observation.

- Gaofen imagery, which lacks built-in preprocessing, was radiometrically calibrated using the method proposed by [50]. This step was essential for extracting reliable radar backscatter intensities.

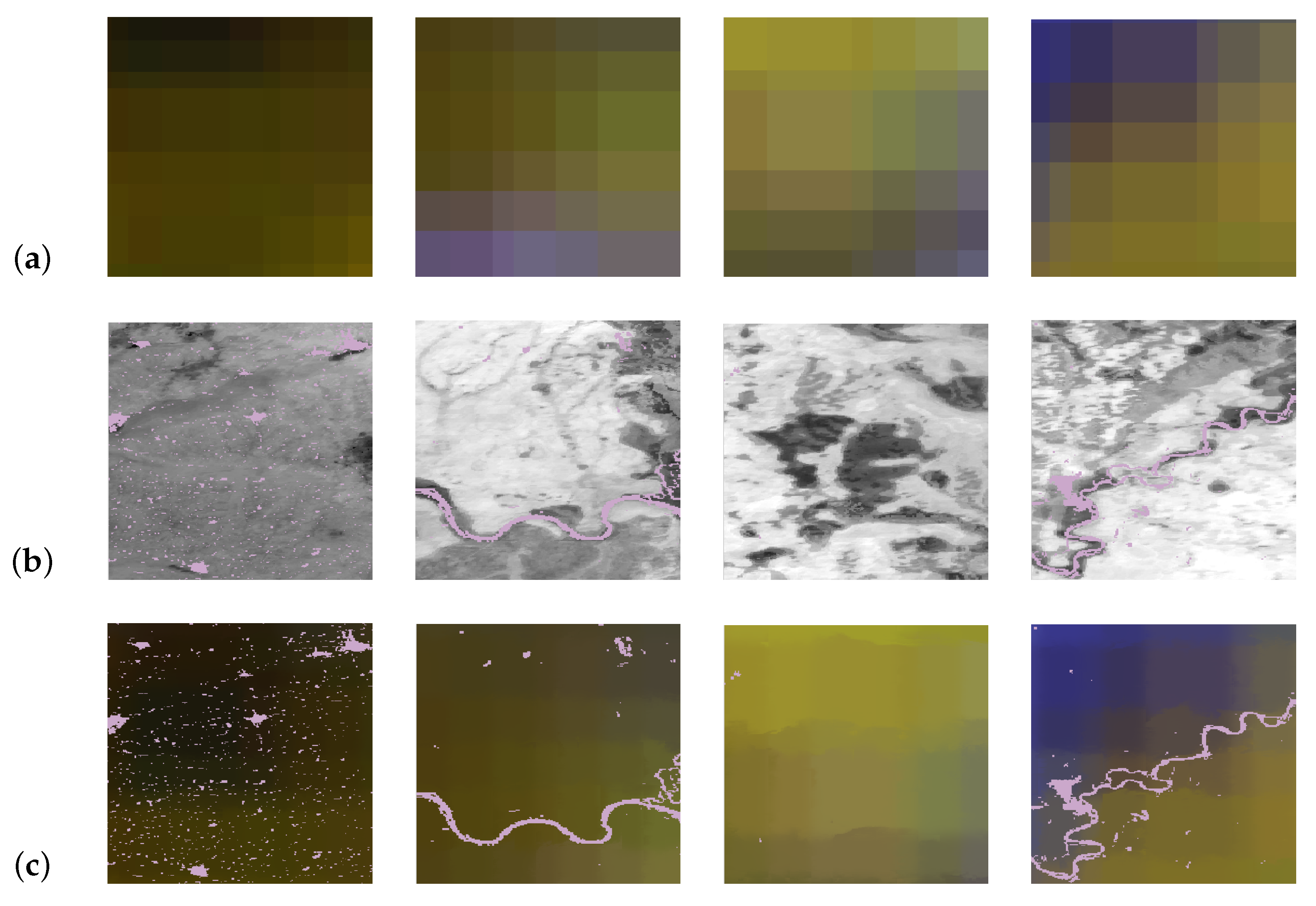

- Sentinel-2 offers two product levels: Level-1C and Level-2A. Although Level-2A data provide improved atmospheric correction, they were not always available for the entire study period. Consequently, these two sources are used in a complementary fashion to enhance spectral and spatial representation in remote sensing analyses.

- Landsat-8 provides both Level-1 and Level-2 data, too. To ensure adequate coverage while maintaining data quality, we also prioritized Level-2 data and used Level-1 data where necessary.

- DEM data were obtained from the ASTER GDEM dataset. In addition to elevation, terrain slope was derived to incorporate topographic features relevant to soil moisture distribution.

- ERA5 climate reanalysis data were aligned with Sentinel-1 acquisition dates. Daily and monthly averages of temperature and precipitation were extracted to capture short- and mid-term atmospheric influences on soil moisture.

- Time: seasonality was represented by encoding the acquisition month of each Sentinel-1 image using a cyclic transformation. This allowed the model to account for seasonal patterns affecting SSM.

- Geolocation information, specifically the latitude and longitude of the image center, was also encoded cyclically. This enabled the model to learn spatial patterns and regional dependencies.

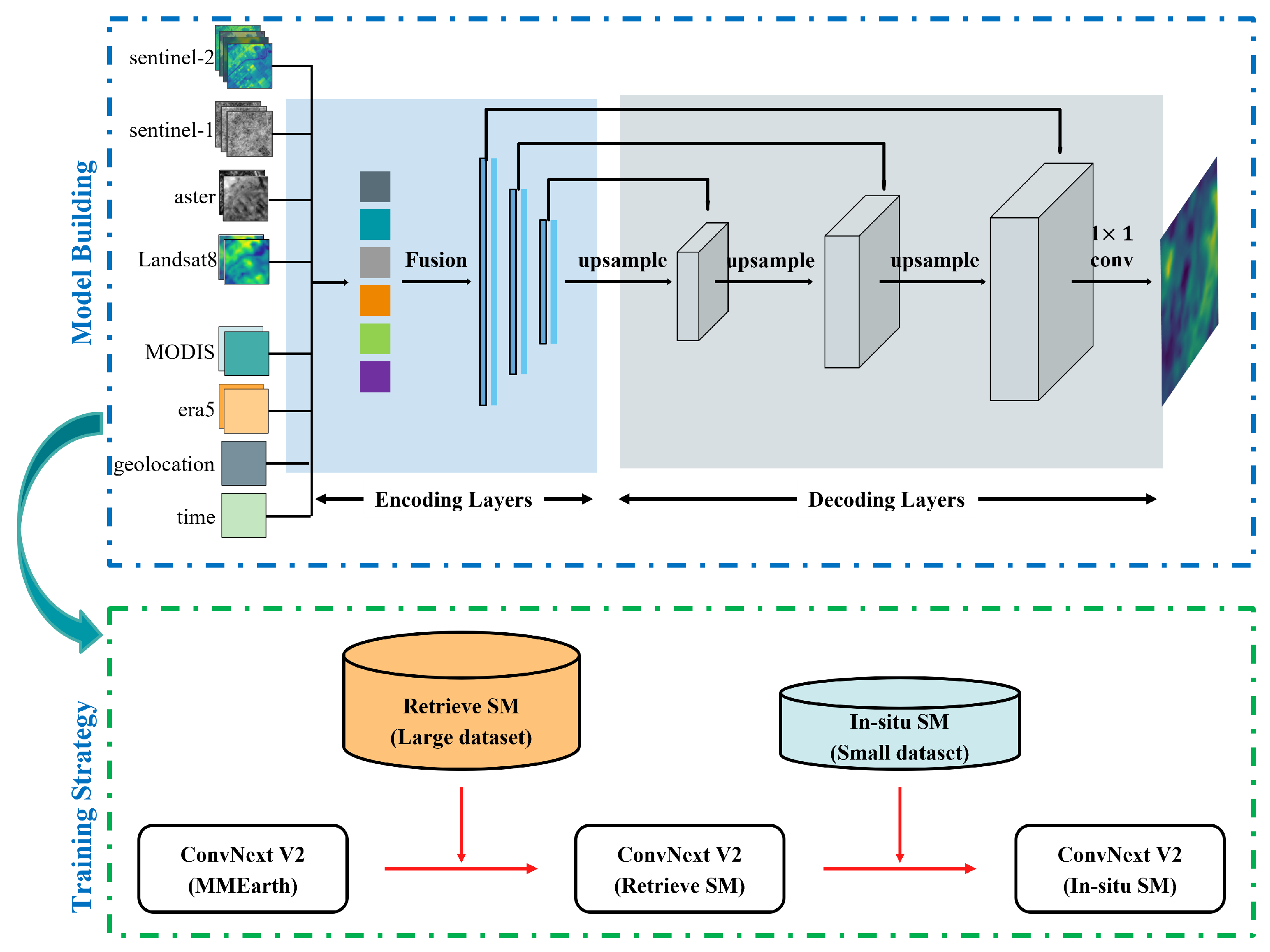

2.3. Methods

- The original classification head is replaced with a single-channel linear output layer to predict soil moisture for each pixel.

- The loss function is changed from cross-entropy to Mean Absolute Error, which better suits the continuous nature of soil moisture values.

- U-Net-style skip connections [53] are added between encoder and decoder stages to preserve spatial details. Feature maps are concatenated channel-wise to retain fine-grained information during upsampling.

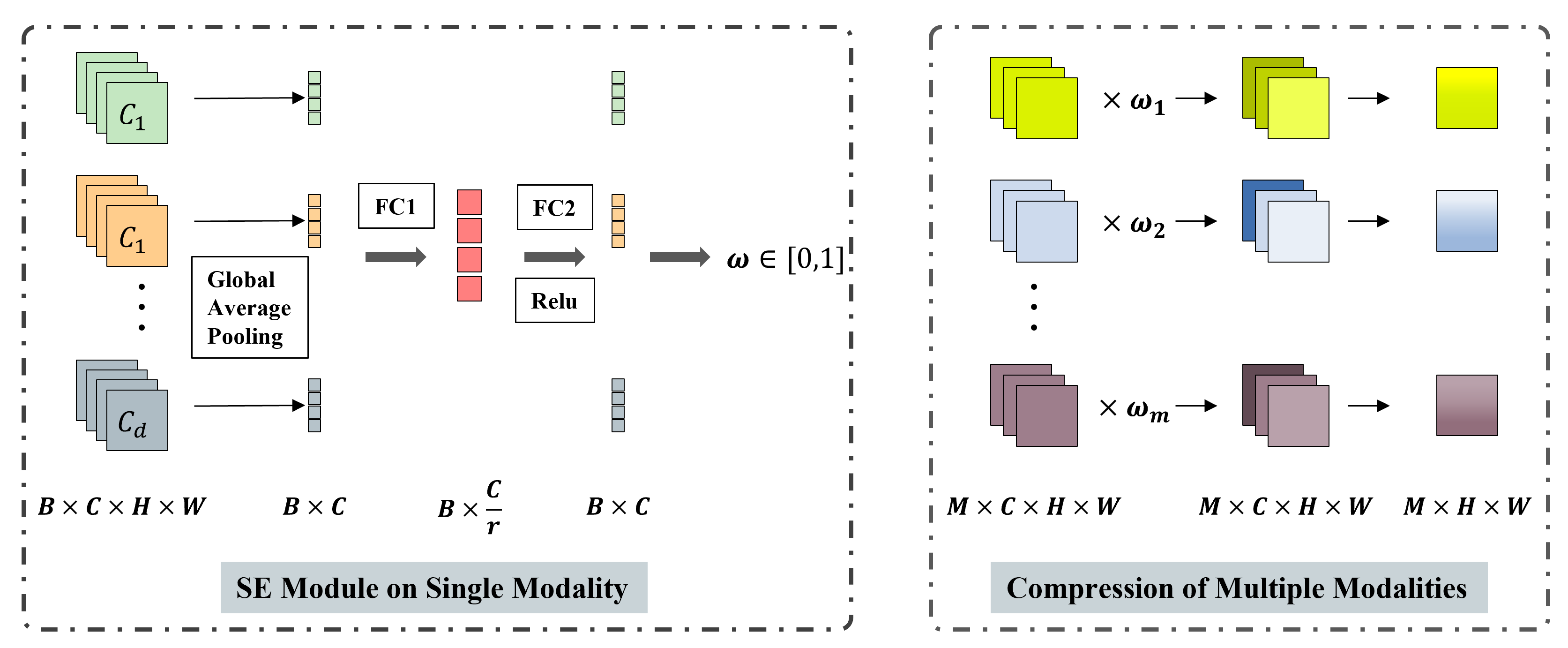

- Global average pooling is applied to each feature map to obtain a channel-wise descriptor:

- The descriptor z is passed through a two-layer MLP ( and ) with ReLU and sigmoid activations to produce the attention weights :

- Each channel is reweighted by its corresponding attention score:

- A convolution is applied to reduce the reweighted feature map to a single-channel representation per modality, allowing unified downstream processing. The complete multimodal fusion workflow is illustrated in Figure 4.

- Pretraining stage: The model is initialized with ConvNeXt V2 weights pretrained on the MMEarth dataset [55], which is specifically designed for multimodal Earth observation tasks and has demonstrated strong performance in various settings.

- Intermediate training stage: The model is further trained on a large-scale and automatically curated soil moisture dataset using SWF labels. This global dataset enables the model to learn generalizable relationships between multimodal remote sensing inputs and soil moisture dynamics.

- Fine-tuning stage: Finally, the model is fine-tuned on a high-quality, small-sample in-situ dataset based on field measurements. The higher label fidelity in this stage enhances the model’s accuracy in specific geographic regions and supports better adaptation to real-world conditions.

3. Results

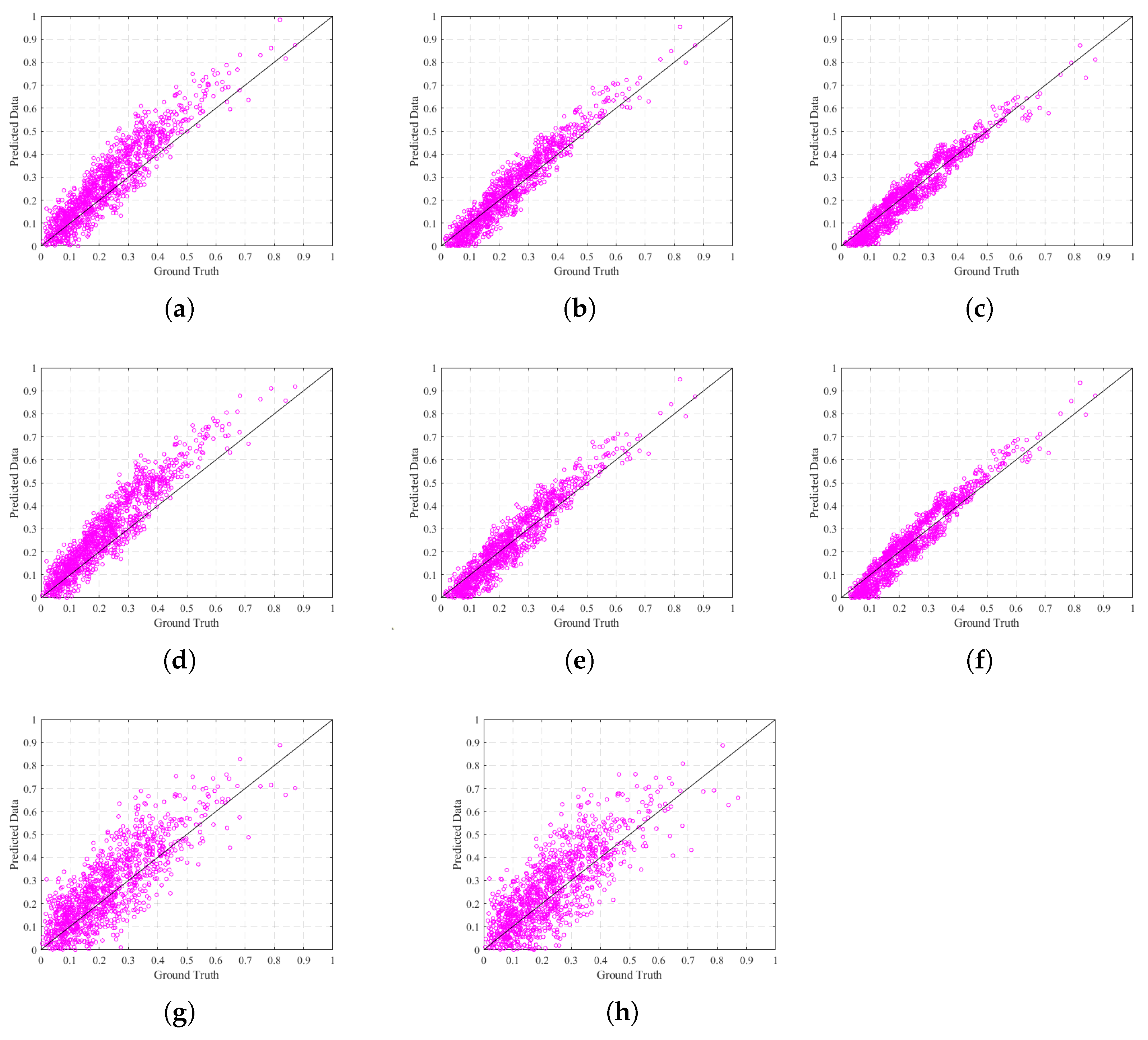

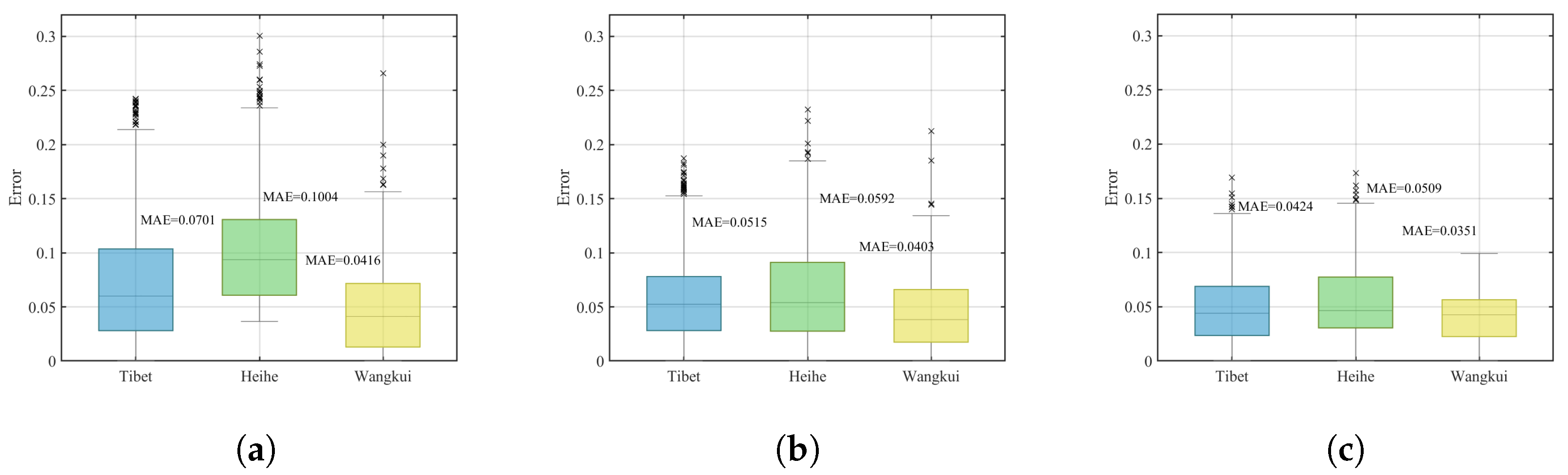

3.1. Intermediate Task Fine-Tuning

3.2. Soil Moisture Estimation Results

3.3. Accuracy of Soil Moisture Estimates over Different Soil Types

4. Discussion

4.1. Contribution of Intermediate Task Fine-Tuning Strategy

4.2. Role of Multimodal Approach

4.3. Underlying Causes of Soil Type Differences

4.4. Main Perspectives of the Multimodal Approach

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Landsat 8: https://www.usgs.gov/landsat-missions (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Sentinel-2: https://www.esa.int/Applications/Observing_the_Earth/Copernicus/Sentinel-2 (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Sentinel-1: https://sentinels.copernicus.eu/copernicus/sentinel-1 (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- ASTER: https://gee-community-catalog.org/projects/aster/ (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- MODIS: https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MCD15A3H.061 (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- ERA5: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/ (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Tibetan Plateau soil temperature and humidity: https://doi.org/10.11888/Soil.tpdc.270110 (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Heihe River Basin soil moisture: https://doi.org/10.11888/Soil.tpdc.270571 and https://doi.org/10.11888/Hydro.tpdc.271137 (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Tibet: https://doi.org/10.11888/Soil.tpdc.270110 (accessed on 12 March 2024).

References

- Shiklomanov, I.A. World Water Resources: A New Appraisal and Assessment for the 21st Century; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO): Paris, France, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Z.; Ciais, P.; Feldman, A.F.; Gentine, P.; Makowski, D.; Prentice, I.C.; Stoy, P.C.; Bastos, A.; Wigneron, J.P. Critical soil moisture thresholds of plant water stress in terrestrial ecosystems. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabq7827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Fernández, J.; González-Zamora, A.; Sánchez, N.; Gumuzzio, A.; Herrero-Jiménez, C. Satellite soil moisture for agricultural drought monitoring: Assessment of the SMOS derived Soil Water Deficit Index. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 177, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Song, J.; Fu, B. Soil moisture determines the recovery time of ecosystems from drought. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 3562–3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandhol, N.; Pandey, S.; Singh, V.P.; Herrera-Estrella, L.; Tran, L.S.P.; Tripathi, D.K. Link between plant phosphate and drought stress responses. Research 2024, 7, 0405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, D.A.; Campbell, C.S.; Hopmans, J.W.; Hornbuckle, B.K.; Jones, S.B.; Knight, R.; Ogden, F.; Selker, J.; Wendroth, O. Soil moisture measurement for ecological and hydrological watershed-scale observatories: A review. Vadose Zone J. 2008, 7, 358–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.A.; Jones, S.B.; Wraith, J.M.; Or, D.; Friedman, S.P. A review of advances in dielectric and electrical conductivity measurement in soils using time domain reflectometry. Vadose Zone J. 2003, 2, 444–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorigo, W.; Himmelbauer, I.; Aberer, D.; Schremmer, L.; Petrakovic, I.; Zappa, L.; Preimesberger, W.; Xaver, A.; Annor, F.; Ardö, J.; et al. The International Soil Moisture Network: Serving Earth system science for over a decade. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. 2021, 2021, 1–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatchford, M.L.; Mannaerts, C.M.; Zeng, Y.; Nouri, H.; Karimi, P. Status of accuracy in remotely sensed and in-situ agricultural water productivity estimates: A review. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 234, 111413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.L.; Leng, P.; Zhou, C.; Chen, K.S.; Zhou, F.C.; Shang, G.F. Soil moisture retrieval from remote sensing measurements: Current knowledge and directions for the future. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2021, 218, 103673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, M.; Parsian, S.; MirMazloumi, S.M.; Aieneh, O. Two new soil moisture indices based on the NIR-red triangle space of Landsat-8 data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2016, 50, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaeian, E.; Sadeghi, M.; Franz, T.E.; Jones, S.; Tuller, M. Mapping soil moisture with the OPtical TRApezoid Model (OPTRAM) based on long-term MODIS observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 211, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Jin, R.; Li, X.; Ma, C.; Qin, J.; Zhang, Y. High spatio-temporal resolution mapping of soil moisture by integrating wireless sensor network observations and MODIS apparent thermal inertia in the Babao River Basin, China. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 191, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, L.; Pan, M.; Wanders, N.; Kumar, D.N.; Wood, E.F. Four decades of microwave satellite soil moisture observations: Part 1. A review of retrieval algorithms. Adv. Water Resour. 2017, 109, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yaari, A.; Wigneron, J.P.; Kerr, Y.; Rodriguez-Fernandez, N.; O’Neill, P.; Jackson, T.; De Lannoy, G.J.M.; Al Bitar, A.; Mialon, A.; Richaume, P.; et al. Evaluating soil moisture retrievals from ESA’s SMOS and NASA’s SMAP brightness temperature datasets. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 193, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, P.; Singh, G.; Das, N.N.; Lohman, R.B. Validation of the NISAR Multi-Scale Soil Moisture Retrieval Algorithm across Various Spatial Resolutions and Landcovers Using the ALOS-2 SAR Data. J. Remote Sens. 2025, 5, 0729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Gaurav, K.; Sonkar, G.K.; Lee, C.C. Strategies to measure soil moisture using traditional methods, automated sensors, remote sensing, and machine learning techniques: Review, bibliometric analysis, applications, research findings, and future directions. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 13605–13635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Jiao, X.; Liu, Y.; Shao, M.; Yu, X.; Bai, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Tuohuti, N.; Liu, S.; et al. Estimation of soil moisture content under high maize canopy coverage from UAV multimodal data and machine learning. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 264, 107530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Song, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, M.; Yang, W. Development of an online prediction system for soil organic matter and soil moisture content based on multi-modal fusion. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 227, 109514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Zhao, W.; Ding, T.; Yin, G. Generation of High-Resolution Surface Soil Moisture over Mountain Areas by Spatially Downscaling Remote Sensing Products Based on Land Surface Temperature–Vegetation Index Feature Space. J. Remote Sens. 2025, 5, 0437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Tian, F. Study on Soil Moisture Status of Soybean and Corn across the Whole Growth Period Based on UAV Multimodal Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, P.; Teng, S.W.; Murshed, M.; Pang, S.; Li, Y.; Lin, H. Crop monitoring by multimodal remote sensing: A review. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2024, 33, 101093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, G.; Zhao, Y.; Fu, L.; Ye, Q. Object detection by channel and spatial exchange for multimodal remote sensing imagery. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 8581–8593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhou, W.; Qian, X.; Yan, W. Progressive adjacent-layer coordination symmetric cascade network for semantic segmentation of multimodal remote sensing images. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 121999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sa, V.R.; Ballard, D.H. Category learning through multimodality sensing. Neural Comput. 1998, 10, 1097–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.P.; Zadeh, A.; Morency, L.P. Foundations & trends in multimodal machine learning: Principles, challenges, and open questions. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Zhu, D.; Li, K.; Gou, C.; Li, F.; Wang, Z.; Zhong, S.; Yu, W.; Nie, X.; Song, Z.; et al. Emerging properties in unified multimodal pretraining. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.14683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Shi, J.; Entekhabi, D.; Jackson, T.J.; Hu, L.; Peng, Z.; Yao, P.; Li, S.; Kang, C.S. Retrievals of soil moisture and vegetation optical depth using a multi-channel collaborative algorithm. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 257, 112321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, R. Global soil moisture data derived through machine learning trained with in-situ measurements. Sci. Data 2021, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, M.; Li, B.; Jiao, X.; Huang, X.; Fan, H.; Lin, R.; Liu, K. Using multimodal remote sensing data to estimate regional-scale soil moisture content: A case study of Beijing, China. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 260, 107298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshome, F.T.; Bayabil, H.K.; Schaffer, B.; Ampatzidis, Y.; Hoogenboom, G. Improving soil moisture prediction with deep learning and machine learning models. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 226, 109414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Gaurav, K. Deep learning and data fusion to estimate surface soil moisture from multi-sensor satellite images. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijaguna, G.; Manjunath, D.; Abouhawwash, M.; Askar, S.S.; Basha, D.K.; Sengupta, J. Deep learning-based improved WCM technique for soil moisture retrieval with satellite images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.; Wang, T.; Munkhdalai, T.; Sordoni, A.; Trischler, A.; Mattarella-Micke, A.; Maji, S.; Iyyer, M. Exploring and predicting transferability across NLP tasks. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.00770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szép, M.; Rueckert, D.; von Eisenhart-Rothe, R.; Hinterwimmer, F. A Practical Guide to Fine-tuning Language Models with Limited Data. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.09539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, O.; Seppi, K.; Gardner, M. When to use multi-task learning vs intermediate fine-tuning for pre-trained encoder transfer learning. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.08124. [Google Scholar]

- Nayak, S.; Ranathunga, S.; Thillainathan, S.; Hung, R.; Rinaldi, A.; Wang, Y.; Mackey, J.; Ho, A.; Lee, E.S.A. Leveraging auxiliary domain parallel data in intermediate task fine-tuning for low-resource translation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.01382. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, L.; Li, S.; Ma, W.; Kang, J.; Xie, B.; Sun, Z.; Zhu, C. Enhancing cross-modal fine-tuning with gradually intermediate modality generation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.09003. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, S.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Effects of straw returning methods on seasonal variation in soil moisture and water storage in Mollisols with different degradation degrees. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 319, 109796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EROS. USGS EROS Archive-Landsat Archives-Landsat 8-9 OLI/TIRS Collection 2 Level-2 Science Products; US Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2020.

- Pahlevan, N.; Chittimalli, S.K.; Balasubramanian, S.V.; Vellucci, V. Sentinel-2/Landsat-8 product consistency and implications for monitoring aquatic systems. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 220, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myneni, R.; Knyazikhin, Y.; Park, T. MODIS/Terra+Aqua Leaf Area Index/FPAR 4-Day L4 Global 500 m SIN Grid V061; NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center: Sioux Falls, SD, USA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Furtak, K.; Wolińska, A. The impact of extreme weather events as a consequence of climate change on the soil moisture and on the quality of the soil environment and agriculture—A review. Catena 2023, 231, 107378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Sabater, J. ERA5-Land monthly averaged data from 1981 to present. Copernic. Clim. Chang. Serv. (C3S) Clim. Data Store (CDS) 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turek, M.E.; Poggio, L.; Batjes, N.H.; Armindo, R.A.; van Lier, Q.d.J.; de Sousa, L.; Heuvelink, G.B. Global mapping of volumetric water retention at 100, 330 and 15,000 cm suction using the WoSIS database. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2023, 11, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.K.; Bindlish, R.; O’Neill, P.; Jackson, T.; Njoku, E.; Dunbar, S.; Chaubell, J.; Piepmeier, J.; Yueh, S.; Entekhabi, D.; et al. Development and assessment of the SMAP enhanced passive soil moisture product. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 204, 931–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Huang, L.; Yang, H.; Zhang, D.; Wu, Z.; Guo, J. Fusion and assessment of high-resolution WorldView-3 satellite imagery using NNDiffuse and Brovey algotirhms. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Beijing, China, 10–15 July 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 2606–2609. [Google Scholar]

- Bob, S.; Yang, K. Time-Lapse Observation Dataset of Soil Temperature and Humidity on the Tibetan Plateau (2008–2016); National Tibetan Plateau Data Center: Lanzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rui, J.; Jian, K. Hourly Soil Moisture Dataset Observed by Eco-Hydrological Sensor Network in the Upper Reaches of Heihe River (2013–2017); National Tibetan Plateau Data Center: Lanzhou, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Liu, L.; Zhou, X. Calibration of SAR Polarimetric Images by Covariance Matching Estimation Technique with Initial Search. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkland, E.J.; Kirkland, E.J. Bilinear interpolation. In Advanced Computing in Electron Microscopy; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 261–263. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Debnath, S.; Hu, R.; Chen, X.; Liu, Z.; Kweon, I.S.; Xie, S. Convnext v2: Co-designing and scaling convnets with masked autoencoders. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 16133–16142. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; Proceedings, Part III 18. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Nedungadi, V.; Kariryaa, A.; Oehmcke, S.; Belongie, S.; Igel, C.; Lang, N. MMEarth: Exploring multi-modal pretext tasks for geospatial representation learning. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 164–182. [Google Scholar]

- Abowarda, A.S.; Bai, L.; Zhang, C.; Long, D.; Li, X.; Huang, Q.; Sun, Z. Generating surface soil moisture at 30 m spatial resolution using both data fusion and machine learning toward better water resources management at the field scale. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 255, 112301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parada, L.M.; Liang, X. Impacts of spatial resolutions and data quality on soil moisture data assimilation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2008, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Dai, J.; Jin, J.; Yuan, S.; Xiong, Z.; Walker, J.P. Are the current expectations for SAR remote sensing of soil moisture using machine learning over-optimistic? IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 4501815. [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi, M.G.; Alemohammad, H.; Jalilvand, E.; Tan, P.N.; Judge, J.; Cosh, M.; Das, N.N. Estimating crop biophysical parameters from satellite-based SAR and optical observations using self-supervised learning with geospatial foundation models. Remote Sens. Environ. 2025, 327, 114825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Lu, J.; Chen, X. An innovative method for measuring the hysteresis effects of soil moisture on meteorological variables at various time scales and climate conditions. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2025, 28, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Miao, L.; Peng, J.; Zhao, T.; Meng, L.; Lu, H.; Peng, Z.; Cosh, M.H.; Fang, B.; Lakshmi, V.; et al. Bridging spatio-temporal discontinuities in global soil moisture mapping by coupling physics in deep learning. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 313, 114371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; Li, T.; Liu, Y.; Tian, J.; Tian, Q.; Li, S.; Feng, H.; Guo, W.; Yang, H.; Yang, G.; et al. A novel vegetation-water resistant soil moisture index for remotely assessing soil surface moisture content under the low-moderate wheat cover. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 224, 109223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragkos, A.; Loukatos, D.; Kargas, G.; Arvanitis, K.G. Response of the TEROS 12 soil moisture sensor under different soils and variable electrical conductivity. Sensors 2024, 24, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Zhang, B.; He, C.; Han, Z.; Bogena, H.R.; Huisman, J.A. Dynamic response patterns of profile soil moisture wetting events under different land covers in the Mountainous area of the Heihe River Watershed, Northwest China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 271, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Fan, L.; Zhao, L.; De Lannoy, G.; Frappart, F.; Peng, J.; Li, X.; Zeng, J.; Al-Yaari, A.; Yang, K.; et al. A first assessment of satellite and reanalysis estimates of surface and root-zone soil moisture over the permafrost region of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 265, 112666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Fang, W.; Fu, H.; Gan, L.; Wang, J.; Gong, P. High-resolution land cover mapping through learning with noise correction. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.J. A review of uncertainty in in situ measurements and data sets of sea surface temperature. Rev. Geophys. 2014, 52, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, R.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, S. Effects of multi-temporal scale drought on vegetation dynamics in Inner Mongolia from 1982 to 2015, China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 136, 108666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhasme, P.; Vagadiya, J.; Bhatia, U. Enhancing predictive skills in physically-consistent way: Physics informed machine learning for hydrological processes. J. Hydrol. 2022, 615, 128618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Level | Type | Product | Resolution | Frequency | Band Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIXEL | Multispectral | Landsat-8 | 30 m | 16 Days | B1-B11 |

| Multispectral | Sentinel-2 | 10–60 m | 5 Days | B1-B12 | |

| SAR | Sentinel-1 | 10 m | 6 Days | VV, VH for ascending/descending orbit (C-band) | |

| SAR | Gaofen | 1 m | N/A | VV, VH, HV, HH (L-band) | |

| DEM | Aster | 30 m | N/A | elevation, slope | |

| IMAGE | Vegetation | MODIS | 500 m | 4 Days | FPAR, LAI |

| Meteorological Reanalysis | era5 | 11,132 m | 1 Month/Day | temperature, precipitation | |

| Geoposition | N/A | N/A | N/A | cyclic encoding of latitude and longitude | |

| Time | N/A | N/A | N/A | cyclic encoding of month |

| Group | RMSE (%) | MAE (%) | ubRMSE (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a1 | 0.1206 | 13.333 | 10.975 | 11.153 |

| a2 | 0.1082 | 13.427 | 10.862 | 12.328 |

| b1 | 0.2462 | 12.344 | 10.078 | 11.145 |

| b2 | 0.2106 | 12.633 | 10.285 | 11.462 |

| c1 | 0.3072 | 11.749 | 9.442 | 11.295 |

| c2 | 0.2941 | 11.946 | 9.6159 | 11.327 |

| Group | RMSE (%) | MAE (%) | ubRMSE (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a1 | 0.6556 | 8.3248 | 6.6762 | 7.0931 |

| a2 | 0.6024 | 8.9441 | 7.1550 | 6.8219 |

| b1 | 0.8454 | 5.5781 | 4.5622 | 5.5780 |

| b2 | 0.8329 | 5.7994 | 4.7828 | 5.7616 |

| c1 | 0.8956 | 4.5834 | 3.8412 | 4.4282 |

| c2 | 0.8701 | 5.1133 | 4.3475 | 5.0135 |

| d1 | 0.4529 | 10.4920 | 8.4348 | 9.9923 |

| d2 | 0.3989 | 10.9971 | 8.8655 | 10.7433 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Liu, L.; Yu, W.; Wang, X. Estimating Soil Moisture Using Multimodal Remote Sensing and Transfer Optimization Techniques. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010084

Liu J, Liu L, Yu W, Wang X. Estimating Soil Moisture Using Multimodal Remote Sensing and Transfer Optimization Techniques. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010084

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jingke, Lin Liu, Weidong Yu, and Xingbin Wang. 2026. "Estimating Soil Moisture Using Multimodal Remote Sensing and Transfer Optimization Techniques" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010084

APA StyleLiu, J., Liu, L., Yu, W., & Wang, X. (2026). Estimating Soil Moisture Using Multimodal Remote Sensing and Transfer Optimization Techniques. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010084