A Global, Multidecadal Carbon Monoxide (CO) Record from the Sounder AIRS/CrIS System

Highlights

Abstract

1. Introduction

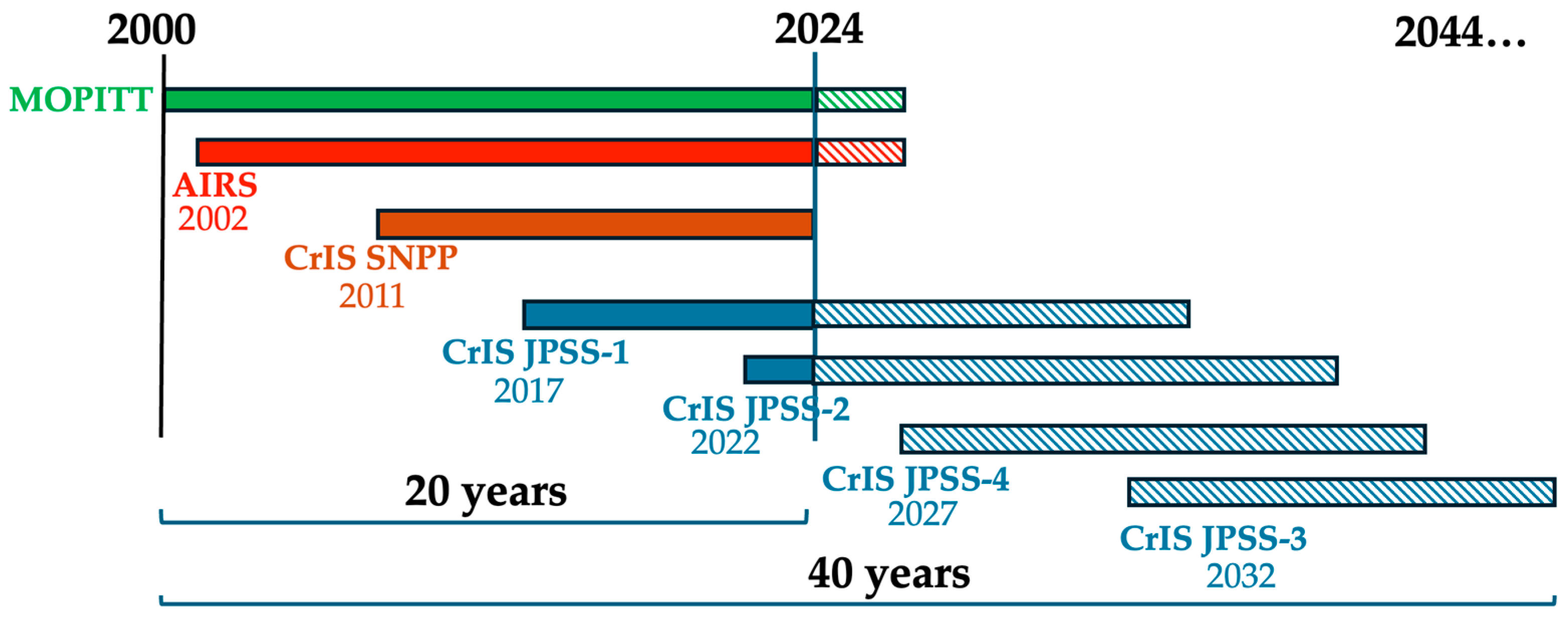

2. The AIRS/CrIS Instrument and Data

3. Annual Cycle and Interannual Variabilities of CO from Sounder Systems

4. More Frequent Wildfires

5. Conclusions & Further Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crutzen, P.J.; Heidt, L.E.; Krasnec, J.P.; Pollock, W.H.; Seiler, W. Biomass burning as a source of atmospheric gases CO, H2, N2O, NO, CH3Cl and COS. Nature 1979, 282, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, D.J. Introduction to Atmospheric Chemistry; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Conte, L.; Szopa, S.; Séférian, R.; Bopp, L. The oceanic cycle of carbon monoxide and its emissions to the atmosphere. Biogeosciences 2019, 16, 881–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, O.; Probert, S.D. Sources of atmospheric carbon monoxide. Appl. Energy 1994, 49, 145–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, K.P. Transport of carbon monoxide from the tropics to the extratropics. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2006, 111, D02107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.P.; Emmons, L.K.; Gille, J.C.; Chu, A.; Attié, J.; Giglio, L.; Wood, S.W.; Haywood, J.; Deeter, M.N.; Massie, S.T.; et al. Satellite-observed pollution from Southern Hemisphere biomass burning. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2006, 111, D14312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Randel, W.J.; Emmons, L.K.; Livesey, N.J. Transport pathways of carbon monoxide in the Asian summer monsoon diagnosed from Model of Ozone and Related Tracers (MOZART). J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2009, 114, D08303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Randel, W.J.; Dessler, A.E.; Schoeberl, M.R.; Kinnison, D.E. Trajectory model simulations of ozone (O3) and carbon monoxide (CO) in the lower stratosphere. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2014, 14, 7135–7147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.W.; Veraverbeke, S.; Andela, N.; Doerr, S.H.; Kolden, C.; Mataveli, G.; Pettinari, M.L.; Le Quéré, C.; Rosan, T.M.; van der Werf, G.R.; et al. Global rise in forest fire emissions linked to climate change in the extratropics. Science 2024, 386, eadl5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchwitz, M.; de Beek, R.; Noël, S.; Burrows, J.P.; Bovensmann, H.; Schneising, O.; Khlystova, I.; Bruns, M.; Bremer, H.; Bergamaschi, P.; et al. Atmospheric carbon gases retrieved from SCIAMACHY by WFM-DOAS: Version 0.5 CO and CH4 and impact of calibration improvements on CO2 retrieval. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2006, 6, 2727–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsdorff, T.; Aan de Brugh, J.; Hu, H.; Aben, I.; Hasekamp, O.; Landgraf, J. Measuring carbon monoxide with TROPOMI: First results and a comparison with ECMWF-IFS analysis data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45, 2826–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seinfeld, J.H.; Pandis, S.N. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, J.S.; Eck, T.F.; Christopher, S.A.; Koppmann, R.; Dubovik, O.; Eleuterio, D.P.; Holben, B.N.; Reid, E.A.; Zhang, J. A review of biomass burning emissions part III: Intensive optical properties of biomass burning particles. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2005, 5, 827–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clerbaux, C.; Hadji-Lazaro, J.; Payan, S.; Camy-Peyret, C.; Mégie, G. Retrieval of CO columns from IMG/ADEOS spectra. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1999, 37, 1657–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, R. TES on the Aura Mission: Scientific objectives, measurements, and analysis overview. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2006, 44, 1102–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, W.W.; Evans, K.D.; Barnet, C.D.; Maddy, E.S.; Sachse, G.W.; Diskin, G.S. Validating the AIRS Version 5 CO retrieval with DACOM in situ measurements during INTEX-A and -B. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2011, 49, 2802–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.; Barnet, C.D. CLIMCAPS observing capability for temperature, moisture, and trace gases from AIRS/AMSU and CrIS/ATMS. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2020, 13, 4437–4459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.; Esmaili, R.; Barnet, C. Community Long-Term Infrared Microwave Combined Atmospheric Product System (CLIMCAPS) Science Application Guides. 2021. Available online: https://docserver.gesdisc.eosdis.nasa.gov/public/project/Sounder/CLIMCAPS_V2_L2_science_guides.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Worden, H.M.; Francis, G.L.; Kulawik, S.S.; Bowman, K.W.; Cady-Pereira, K.; Fu, D.; Hegarty, J.D.; Kantchev, V.; Luo, M.; Payne, V.H.; et al. TROPESS/CrIS carbon monoxide profile validation with NOAA GML and ATom in situ aircraft observations. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2022, 15, 5383–5398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, M.; Clerbaux, C.; Bouarar, I.; Coheur, P.-F.; Deeter, M.N.; Edwards, D.P.; Francis, G.; Gille, J.C.; Hadji-Lazaro, J.; Hurtmans, D.; et al. An examination of the long-term CO records from MOPITT and IASI: Comparison of retrieval methodology. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2015, 8, 4313–4328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barret, B.; Loicq, P.; Le Flochmoën, E.; Bennouna, Y.; Hadji-Lazaro, J.; Hurtmans, D.; Sauvage, B. Validation of 12 years (2008–2019) of IASI-A CO with IAGOS aircraft observations. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2025, 18, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.C. Global carbon monoxide retrieval from the hyperspectral infrared atmospheric sounder-II onboard FengYun-3E in a dawn-dusk sun-synchronous orbit. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2025, 333, 109336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.-C.; Lee, L.; Qi, C. Diurnal carbon monoxide observed from a geostationary infrared hyperspectral sounder: First result from GIIRS on board FengYun-4B. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2023, 16, 3059–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandell, J.; Stuhlmann, R. Limitations to a Geostationary Infrared Sounder due to Diffraction: The Meteosat Third Generation Infrared Sounder (MTG IRS). J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2007, 24, 1740–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naus, S.; Domingues, L.G.; Krol, M.; Luijkx, I.T.; Gatti, L.V.; Miller, J.B.; Gloor, E.; Basu, S.; Correia, C.; Koren, G.; et al. Sixteen years of MOPITT satellite data strongly constrain Amazon CO fire emissions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2022, 22, 14735–14750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, D.; Chen, J.; Anderson, K.; Makar, P.; McLinden, C.A.; Dammers, E.; Fogal, A. Biomass burning CO emissions: Exploring insights through TROPOMI-derived emissions and emission coefficients. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2024, 24, 10159–10186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.; Liu, J.; Bowman, K.W.; Pascolini-Campbell, M.; Chatterjee, A.; Pandey, S.; Miyazaki, K.; van der Werf, G.R.; Wunch, D.; Wennberg, P.O.; et al. Carbon emissions from the 2023 Canadian wildfires. Nature 2024, 633, 835–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marey, H.S.; Drummond, J.R.; Jones, D.B.A.; Worden, H.; Clerbaux, C.; Borsdorff, T.; Gille, J. A comparative analysis of satellite-derived CO retrievals during the 2020 wildfires in North America. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2024, 129, e2023JD039876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, R.R.; Park, M.; Worden, H.M.; Tang, W.; Edwards, D.P.; Gaubert, B.; Deeter, M.N.; Sullivan, T.; Ru, M.; Chin, M.; et al. New seasonal pattern of pollution emerges from changing North American wildfires. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurganov, L.; Rakitin, V. Two Decades of Satellite Observations of Carbon Monoxide Confirm the Increase in Northern Hemispheric Wildfires. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedelius, J.K.; Toon, G.C.; Buchholz, R.R.; Iraci, L.T.; Podolske, J.R.; Roehl, C.M.; Wennberg, P.O.; Worden, H.M.; Wunch, D. Regional and urban column CO trends and anomalies as observed by MOPITT over 16 years. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2021, 126, e2020JD033967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, K.; Sekiya, T.; Fu, D.; Bowman, K.W.; Kulawik, S.S.; Sudo, K.; Walker, T.; Kanaya, Y.; Takigawa, M.; Ogochi, K.; et al. Balance of emission and dynamical controls on ozone during the Korea-United States Air Quality campaign from multiconstituent satellite data assimilation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2019, 124, 387–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaubert, B.; Edwards, D.P.; Anderson, J.L.; Arellano, A.F.; Barré, J.; Buchholz, R.R.; Darras, S.; Emmons, L.K.; Fillmore, D.; Granier, C.; et al. Global Scale Inversions from MOPITT CO and MODIS AOD. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, R.R.; Worden, H.M.; Park, M.; Francis, G.; Deeter, M.N.; Edwards, D.P.; Emmons, L.K.; Gaubert, B.; Gille, J.; Martínez-Alonso, S.; et al. Air pollution trends measured from Terra: CO and AOD over industrial, fire-prone, and background regions. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 256, 112275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahine, M.T.; Pagano, T.S.; Aumann, H.H.; Atlas, R.; Barnet, C.; Blaisdell, J.; Chen, L.; Divakarla, M.; Fetzer, E.J.; Goldberg, M.; et al. Improving Weather Forecasting and Providing New Data on Greenhouse Gases. AIRS. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 2006, 87, 911–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, W.W.; Barnet, C.; Strow, L.; Chahine, M.T.; McCourt, M.L.; Warner, J.X.; Novelli, P.C.; Korontzi, S.; Maddy, E.S.; Datta, S. Daily global maps of carbon monoxide from NASA’s Atmospheric Infrared Sounder. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, L11801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Payne, V.; Manning, E.; Yue, Q.; Wong, S.; Lambrigtsen, B.H.; Fetzer, E.; Monarrez, R.; Pagano, T.; Fishbein, E.; et al. Testing Report for the AIRS v7 and CLIMCAPS-Aqua v2 Level-3 Monthly Gridded Composition Products; Jet Propulsion Laboratory/California Institute of Technology: La Cañada Flintridge, CA, USA, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Payne, V.; Manning, E.; Wong, S.; Yue, Q.; Lambrigtsen, B.H.; Fetzer, E.; Monarrez, R. Test Report of AIRS v7 and CLIMCAPS-Aqua v02.39 Level-2 Carbon Monoxide (CO) Profiles; Jet Propulsion Laboratory/California Institute of Technology: La Cañada Flintridge, CA, USA, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Warner, J.; Comer, M.M.; Barnet, C.D.; McMillan, W.W.; Wolf, W.; Maddy, E.; Sachse, G. A comparison of satellite tropospheric carbon monoxide measurements from AIRS and MOPITT during INTEX-A. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2007, 112, D12S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worden, H.M.; Deeter, M.N.; Frankenberg, C.; George, M.; Nichitiu, F.; Worden, J.; Aben, I.; Bowman, K.W.; Clerbaux, C.; Coheur, P.F.; et al. Decadal record of satellite carbon monoxide observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 13, 837–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Han, H.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, H.; Meng, L.; Li, Y.C.; Liu, Y. Satellite-Observed Variations and Trends in Carbon Monoxide over Asia and Their Sensitivities to Biomass Burning. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Der Werf, G.R.; Randerson, J.T.; Giglio, L.; Van Leeuwen, T.T.; Chen, Y.; Rogers, B.M.; Mu, M.; Van Marle, M.J.; Morton, D.C.; Collatz, G.J.; et al. Global fire emissions estimates during 1997–2016. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2017, 9, 697–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susskind, J.; Barnet, C.D.; Blaisdell, J.M. Retrieval of atmospheric and surface parameters from AIRS/AMSU/HSB data in the presence of clouds. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2003, 41, 390–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, J.X.; Wei, Z.; Strow, L.L.; Barnet, C.D.; Sparling, L.C.; Diskin, G.; Sachse, G. Improved agreement of AIRS tropospheric carbon monoxide products with other EOS sensors using optimal estimation retrievals. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010, 10, 9521–9533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.; Barnet, C.D. CLIMCAPS—A NASA long-term product for infrared + microwave atmospheric soundings. Earth Space Sci. 2023, 10, e2022EA002701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irion, F.W.; Kahn, B.H.; Schreier, M.M.; Fetzer, E.J.; Fishbein, E.; Fu, D.; Kalmus, P.; Wilson, R.C.; Wong, S.; Yue, Q. Single-footprint retrievals of temperature, water vapor and cloud properties from AIRS. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2018, 11, 971–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulawik, S.S.; Worden, J.R.; Payne, V.H.; Fu, D.; Wofsy, S.C.; McKain, K.; Sweeney, C.; Daube, B.C., Jr.; Lipton, A.; Polonsky, I.; et al. Evaluation of single-footprint AIRS CH4 profile retrieval uncertainties using aircraft profile measurements. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2021, 14, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegarty, J.D.; Cady-Pereira, K.E.; Payne, V.H.; Kulawik, S.S.; Worden, J.R.; Kantchev, V.; Worden, H.M.; McKain, K.; Pittman, J.V.; Commane, R.; et al. Validation and error estimation of AIRS MUSES CO profiles with HIPPO, ATom, and NOAA GML aircraft observations. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2022, 15, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G.P.; Clough, S.A.; Kneizys, F.X.; Chetwynd, J.H.; Shettle, E.P. AFGL Atmospheric Constituent Profiles (0.120 km); Technical Report AFGL–TR–86–0110; Air Force Geophysics Lab Hanscom AFB: Bedford, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Gambacorta, A.; Barnet, C.; Wolf, W.; King, T.; Maddy, E.; Strow, L.; Xiong, X.; Nalli, N.; Goldberg, M. An Experiment Using High Spectral Resolution CrIS Measurements for Atmospheric Trace Gases: Carbon Monoxide Retrieval Impact Study. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2014, 11, 1639–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeter, M.N.; Martínez-Alonso, S.; Edwards, D.P.; Emmons, L.K.; Gille, J.C.; Worden, H.M.; Pittman, J.V.; Daube, B.C.; Wofsy, S.C. Validation of MOPITT Version 5 thermal-infrared, near-infrared, and multispectral carbon monoxide profile retrievals for 2000–2011. J. Geophys. Res. 2013, 118, 6710–6725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeter, M.; Francis, G.; Gille, J.; Mao, D.; Martínez-Alonso, S.; Worden, H.; Ziskin, D.; Drummond, J.; Commane, R.; Diskin, G.; et al. The MOPITT Version 9 CO product: Sampling enhancements and validation. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2022, 15, 2325–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoesly, R.; Smith, S.J.; Prime, N.; Ahsan, H.; Suchyta, H.; O’Rourke, P.; Crippa, M.; Klimont, Z.; Guizzardi, D.; Behrendt, J.; et al. CEDS v_2024_07_08 Release Emission Data (v_2024_07_08) [Data Set]; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, R.D.; van der Werf, G.R.; Fanin, T.; Fetzer, E.J.; Fuller, R.; Jethva, H.; Levy, R.; Livesey, N.J.; Luo, M.; Torres, O.; et al. Indonesian fire activity and smoke pollution in 2015 show persistent nonlinear sensitivity to El Niño-induced drought. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 9204–9209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobreira, E.; Lázaro, W.L.; Vitorino, B.D.; da Frota, A.V.B.; Young, C.E.F.; de Souza Campos, D.V.; Viana, C.R.S.; de Oliveira, E.; López-Ramirez, L.; de Souza, A.R.; et al. Wildfires and their toll on Brazil: Who’s counting the cost? Perspect. Ecol. Conserv. 2025, 23, 214–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Ciais, P.; Chevallier, F.; Yang, H.; Canadell, J.G.; Chen, Y.; van der Velde, I.R.; Aben, I.; Chuvieco, E.; Davis, S.J.; et al. Record-High CO2 Emissions from Boreal Fires in 2021. Science 2023, 379, 912–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petetin, H.; Sauvage, B.; Parrington, M.; Clark, H.; Fontaine, A.; Athier, G.; Blot, R.; Boulanger, D.; Cousin, J.-M.; Nédélec, P.; et al. The role of biomass burning as derived from the tropospheric CO vertical profiles measured by IAGOS aircraft in 2002–2017. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 17277–17306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, W.M.; Cochrane, M.A.; Freeborn, P.H.; Holden, Z.A.; Brown, T.J.; Williamson, G.J.; Bowman, D.M.J.S. Climate-induced variations in global wildfire danger from 1979 to 2013. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilmot, T.Y.; Mallia, D.V.; Hallar, A.G.; Lin, J.C. Wildfire plumes in the Western US are reaching greater heights and injecting more aerosols aloft as wildfire activity intensifies. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, C.X.; Williamson, G.J.; Bowman, D.M.J.S. Increasing frequency and intensity of the most extreme wildfires on Earth. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 8, 1420–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, G.; Zhang, Y. Increased atmospheric aridity and reduced precipitation drive the 2023 extreme wildfire season in Canada. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2025, 52, e2024GL114492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrangi, A.; Fetzer, E.J.; Granger, S.L. Early detection of drought onset using near surface temperature and humidity observed from space. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2016, 37, 3911–3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giglio, L.; Schroeder, W.; Justice, C.O. The collection 6 MODIS active fire detection algorithm and fire products. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 178, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostoja, S.M.; Crimmins, A.R.; Byron, R.G.; East, A.E.; Méndez, M.; O’Neill, S.M.; Peterson, D.L.; Pierce, J.R.; Raymond, C.; Tripati, A.; et al. Focus on western wildfires. In Fifth National Climate Assessment; USGCRP (U.S. Global Change Research Program): Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Algorithm | Input Radiance | A Priori | A Priori Details | Time Period | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L2 CO Product | ||||||

| AIRS v7 | AIRS Science Team v7 | AIRS | COfgtype = 3 | MOPITT v4 clim. NH/SH | 2003–2025 | |

| CLIMCAPS-Aqua | CLIMCAPS | AIRS | COfgtype = 2 | AFGL_MOPP, static profile | 2003–2025 | |

| CLIMCAPS-SNPP | CLIMCAPS | CrIS | COfgtype = 4 | AFGL_MOPP + MOPITT v4 clim. NH/SH | 2015–2021 | |

| CLIMCAPS-JPSS1 | CLIMCAPS | CrIS | COfgtype = 4 | AFGL_MOPP + MOPITT v4 clim. NH/SH | 2018–2025 | |

| Datasets | AIRS v7 500 hPa CO | CC-Aqua 500 hPa CO | MOPITT TIR Column CO | MOPITT TIR + NIR Column CO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latitude Bands | |||||

| 60–90°N | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.95 | |

| 30–60°N | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.97 | |

| 30°N-S | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.98 | |

| 30–60°S | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.98 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, T.; Payne, V.H.; Manning, E.; Pagano, T.S.; Lambrigtsen, B.; Monarrez, R. A Global, Multidecadal Carbon Monoxide (CO) Record from the Sounder AIRS/CrIS System. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010005

Wang T, Payne VH, Manning E, Pagano TS, Lambrigtsen B, Monarrez R. A Global, Multidecadal Carbon Monoxide (CO) Record from the Sounder AIRS/CrIS System. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Tao, Vivienne H. Payne, Evan Manning, Thomas S. Pagano, Bjorn Lambrigtsen, and Ruth Monarrez. 2026. "A Global, Multidecadal Carbon Monoxide (CO) Record from the Sounder AIRS/CrIS System" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010005

APA StyleWang, T., Payne, V. H., Manning, E., Pagano, T. S., Lambrigtsen, B., & Monarrez, R. (2026). A Global, Multidecadal Carbon Monoxide (CO) Record from the Sounder AIRS/CrIS System. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010005