Feature Disentanglement Based on Dual-Mask-Guided Slot Attention for SAR ATR Across Backgrounds

Highlights

- Proposes FDSANet, a feature disentanglement network that employs dual mask-guided slot attention to separate target and background features for classification.

- Experiments on the MSTAR and OpenSARShip datasets demonstrate a 2% accuracy improvement over advanced algorithms.

- Alleviates the overfitting problem caused by limited SAR samples and enhances the cross-background generalization ability of target recognition.

- Provides a generalizable solution for SAR automatic target recognition in complex environments.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Slot attention-enhanced autoencoder framework. This paper extend a conventional autoencoder-based classifier by introducing slot attention and designing a slot feature-selection module. These improvements enhance the interpretability and discriminative power of the latent representations, thereby improving the model’s generalization ability across varying background conditions.

- Dual-mask guided slot attention. To further suppress background clutter, we introduce a dual-mask strategy: (i) a target mask derived from prior knowledge guides slot attention to distinguish between the target features and strong clutter points; and (ii) a feature mask adaptively re-weights slot outputs, enhancing feature disentanglement. In addition, a global histogram–matching pre-processing step normalizes intensity distributions, sharpening target edges in SAR images and stabilizing mask generation.

- CAM-Based Slot Selection module. A slot selection method based on the class activation heat map (CAM) is designed. Slot features are an abstract representation that is difficult for humans to understand. Therefore, CAM is used for feature selection. The slots where the activation area is concentrated in the target part are taken as the selection results. This method demonstrates significant stability.

2. Methods

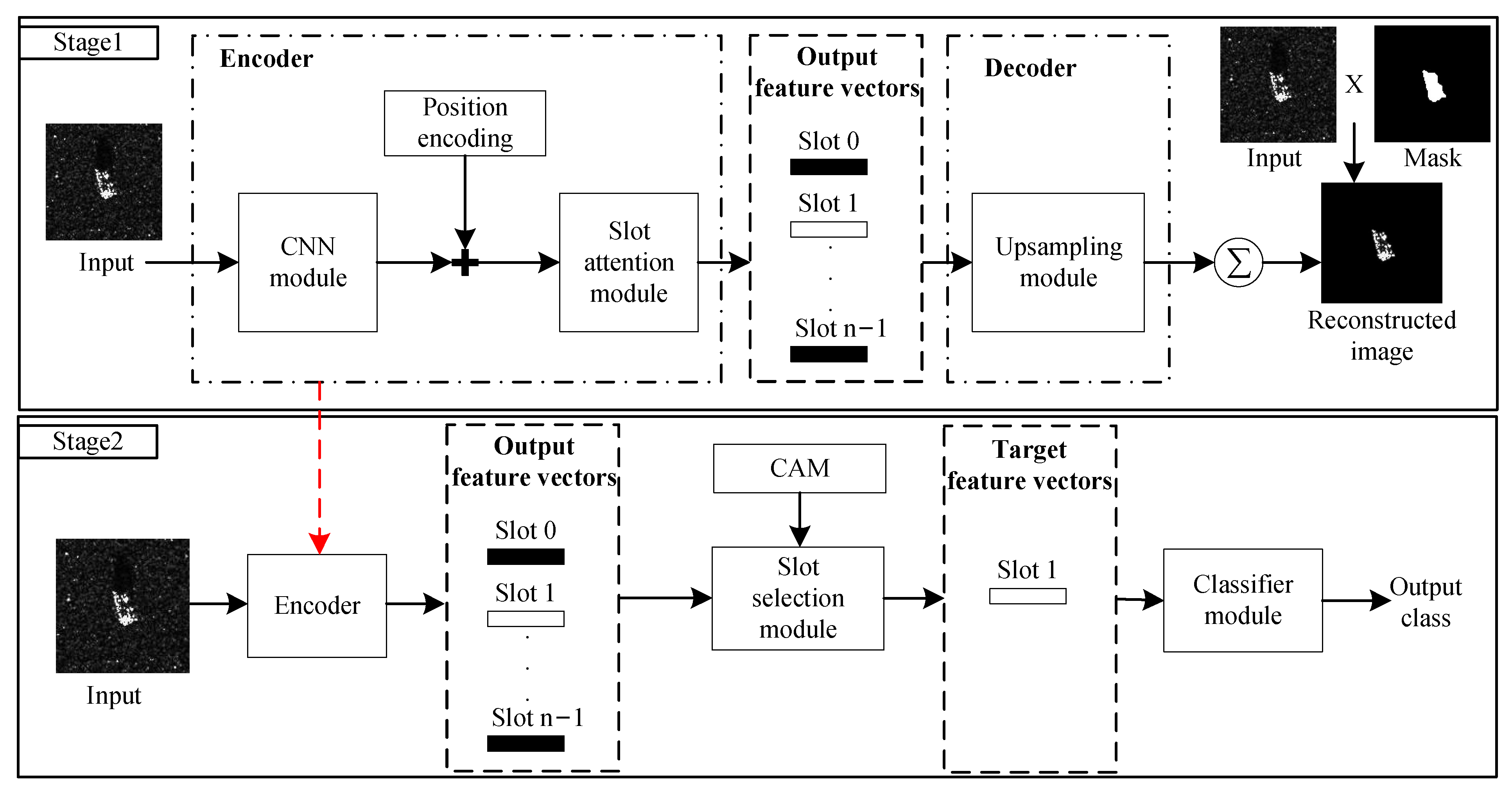

2.1. Overall Framework

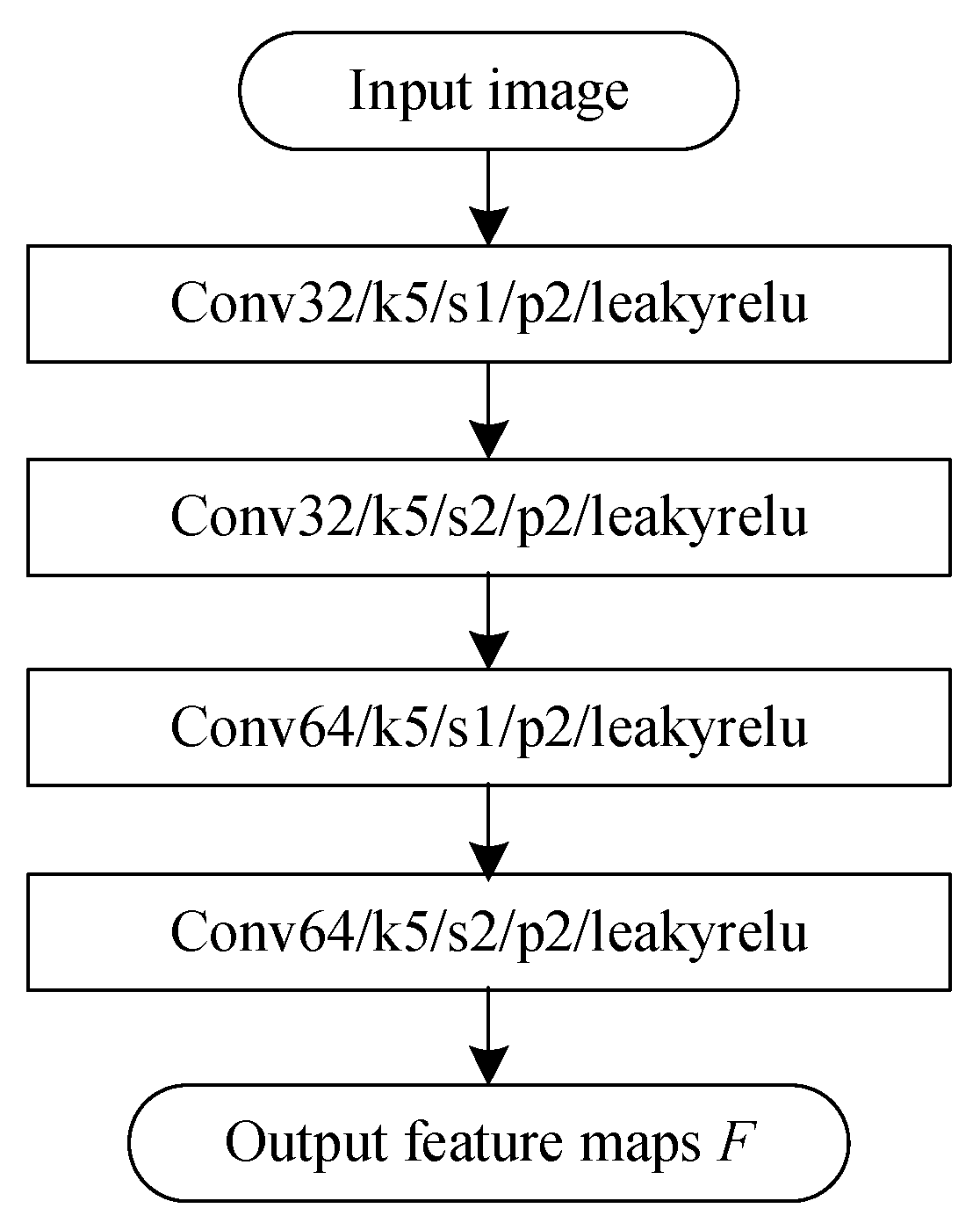

2.2. CNN Module and Position Encoding

2.3. Slot Attention Module

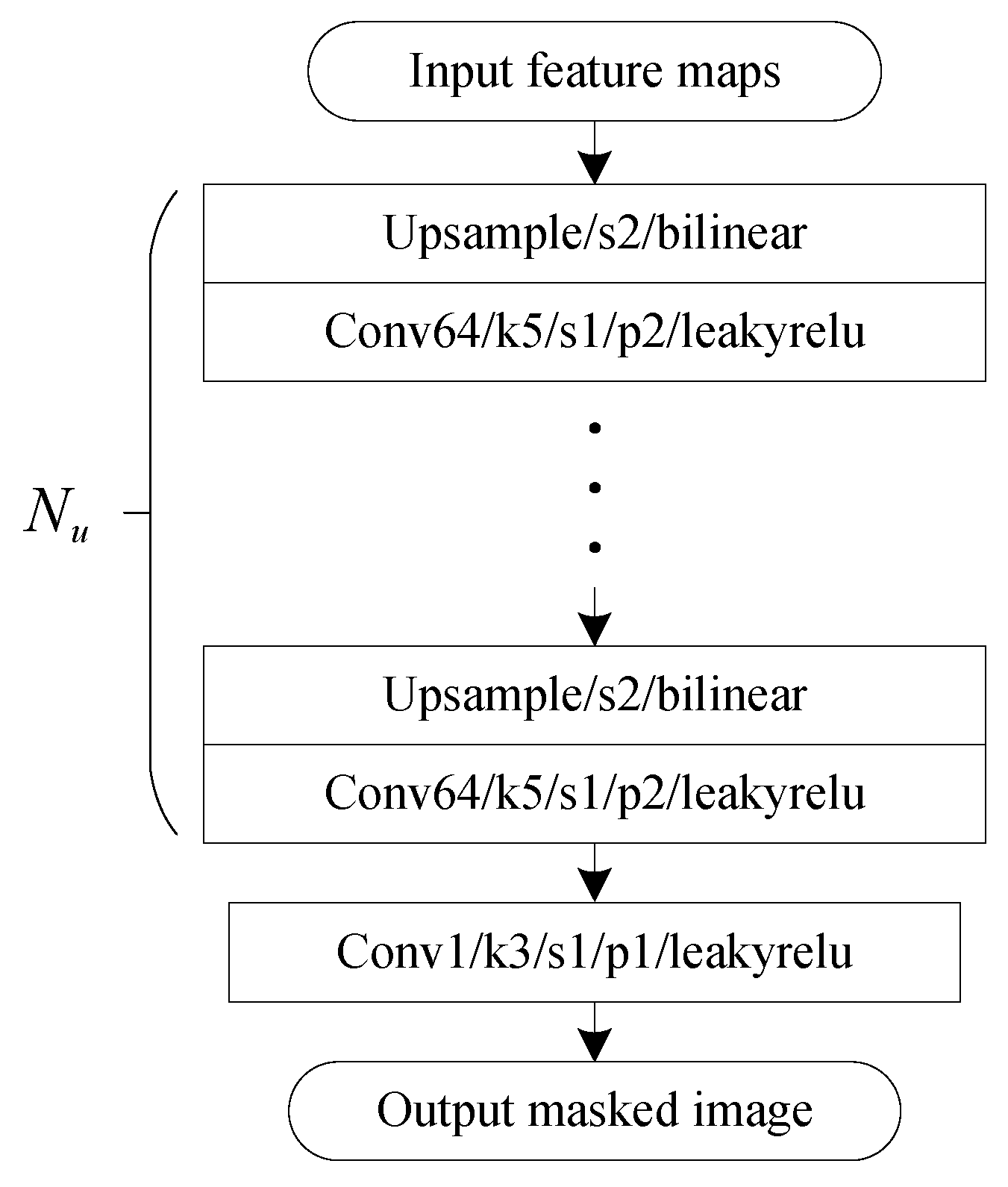

2.4. Upsampling Module

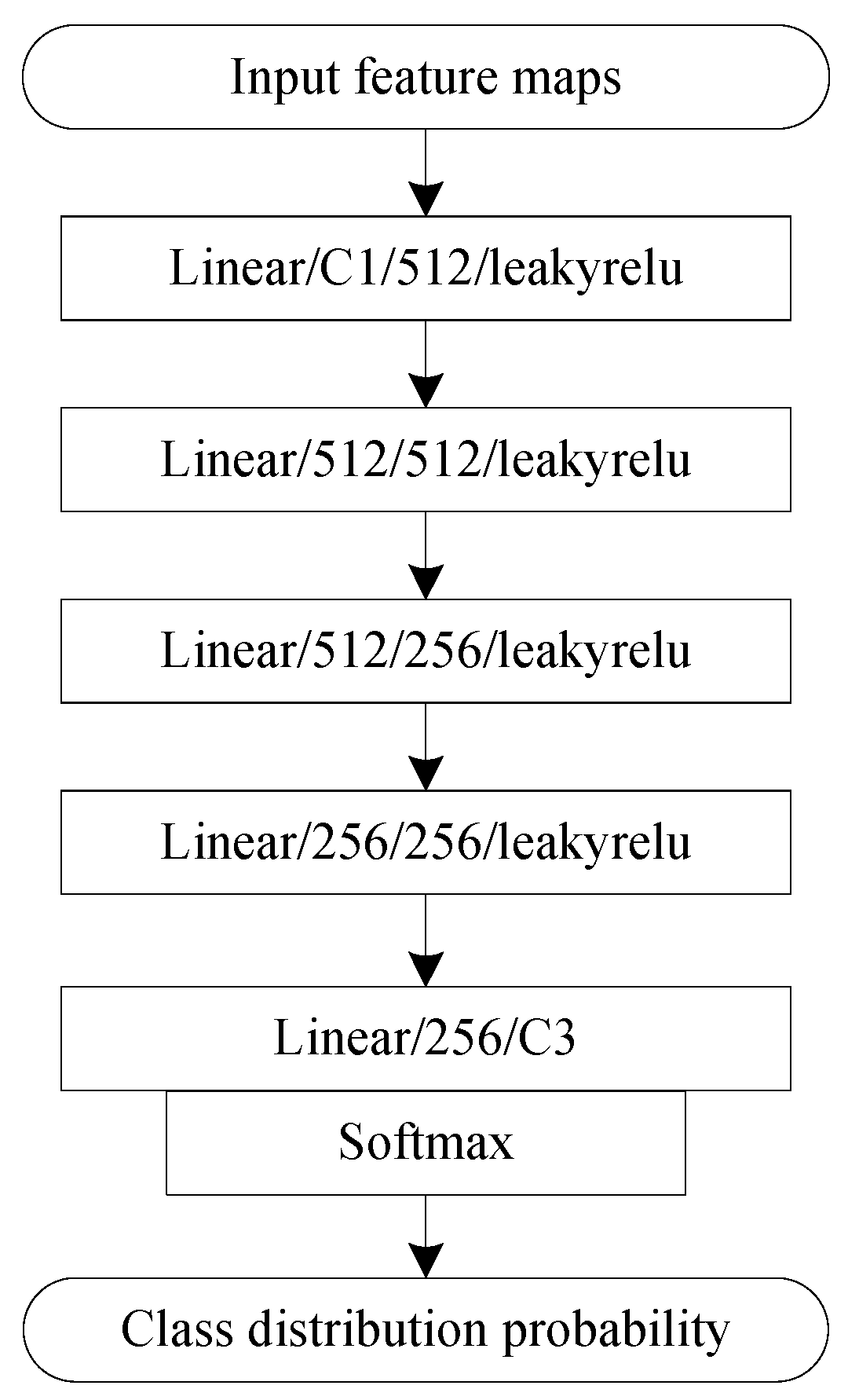

2.5. Slot Selection Module and Classification Module

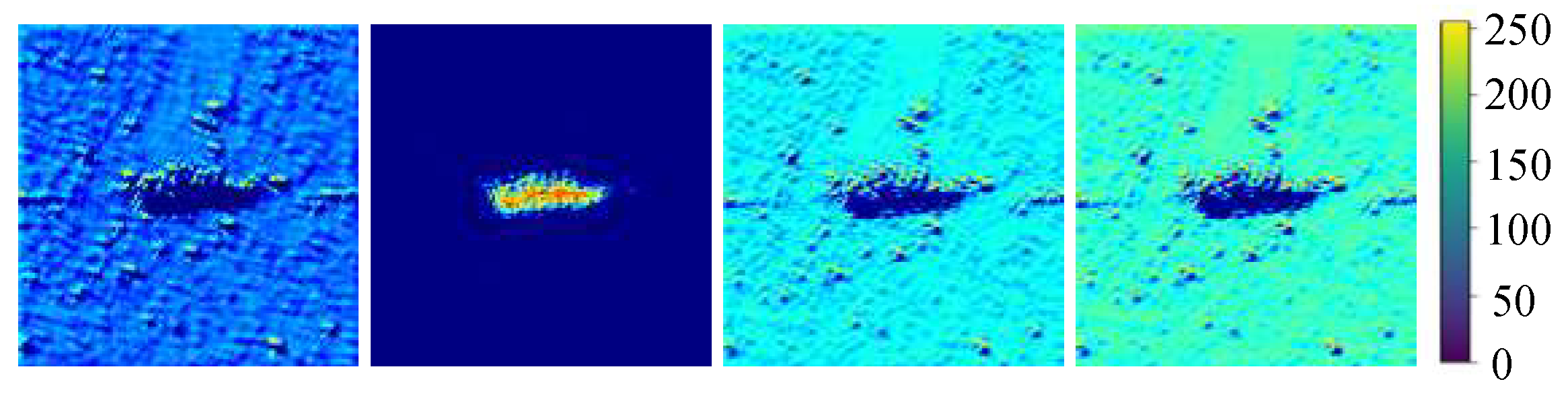

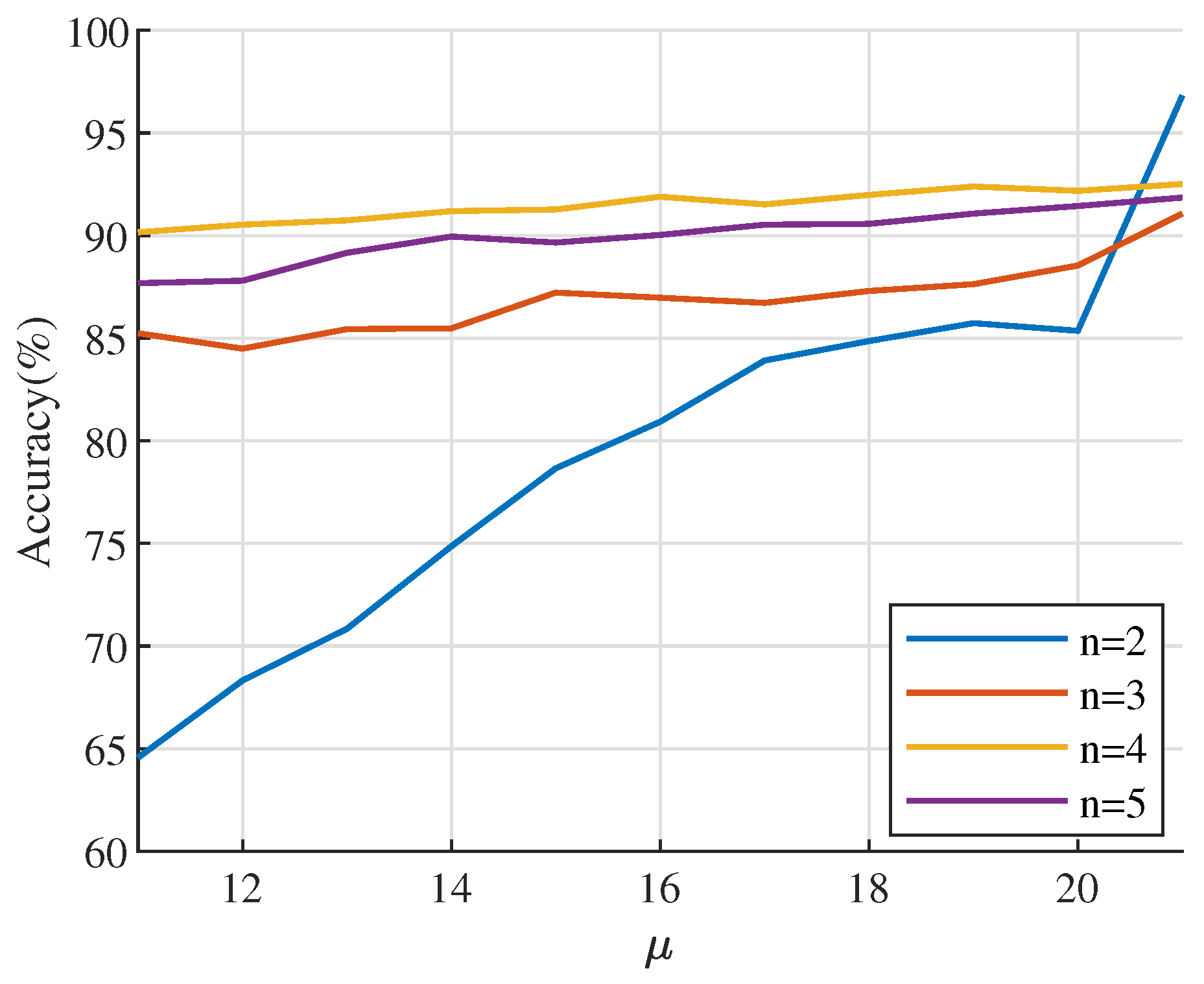

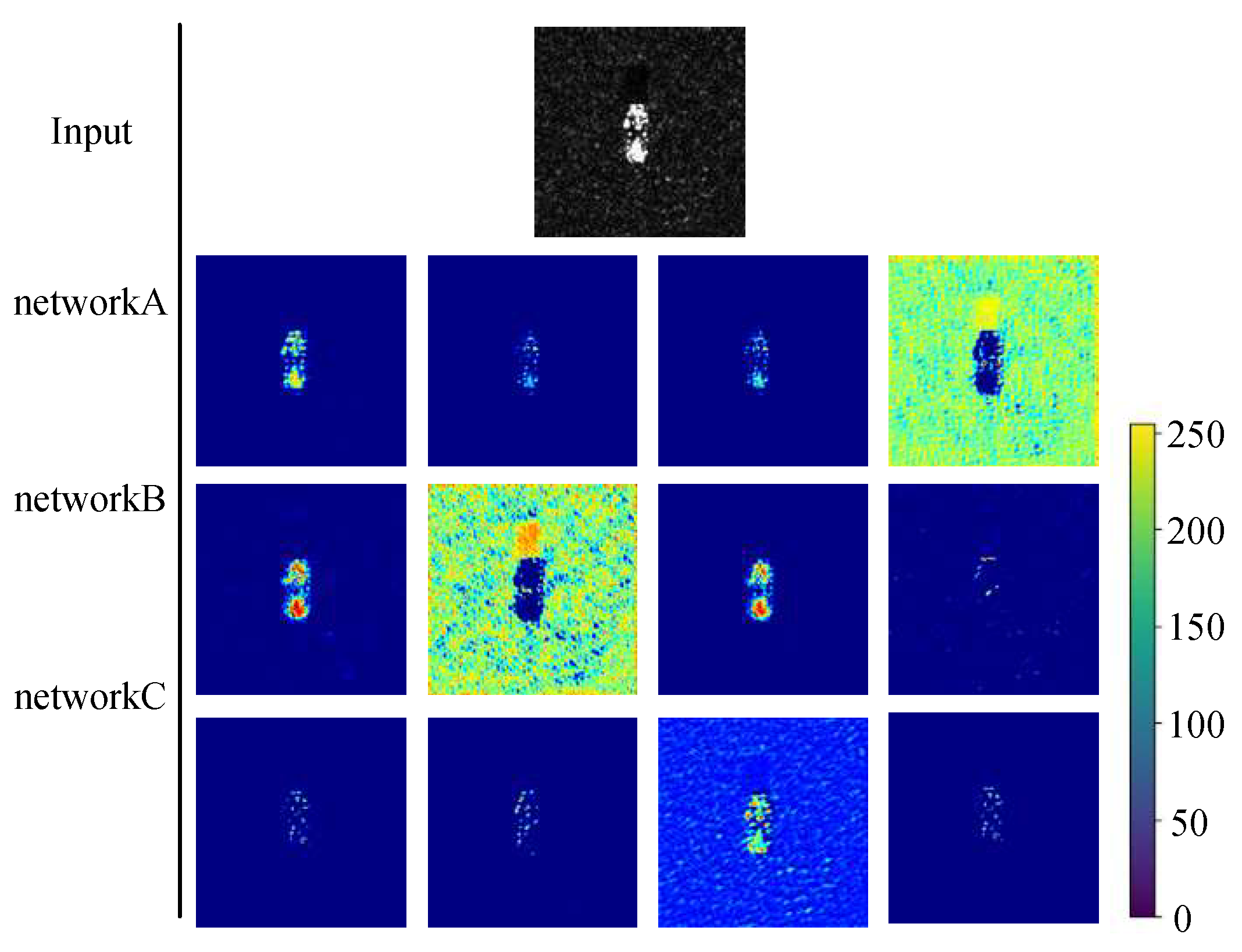

- Compute the mean of each feature in and calculate the CAM of the first convolutional layer for these n means, resulting in n CAMs. Figure 5 illustrates a schematic of CAM. The four subfigures correspond to the four CAMs generated from the four means when n = 4.

- Construct a mask matrix of size . The central region occupying approximately 9% of the total elements (rounded to the nearest integer) is set to 1, while the remaining elements are set to 0. Calculate the total energy and of different regions of the CAM according to the following formula.where , , ⊙ represents the hadamard product, is an all-ones matrix.

- The features corresponding to the CAMs that satisfy the following conditions are selected as the output of this module.where , = 1 in this paper, . The first condition ensures that the central region of the CAM maintains a non-zero energy, thereby filtering out slots unrelated to either the target or the background. The parameter represents the minimum edge energy of the CAM, and the corresponding slot is considered to be focused on the target. The constants 3 and 5 in the second condition serve as empirical offset terms that relax the CAM response boundary, enabling a more robust slot selection. Finally, if multiple slots satisfy these conditions, their features are summed and output together.

2.6. Loss Function

3. Experimental Results and the Discussion

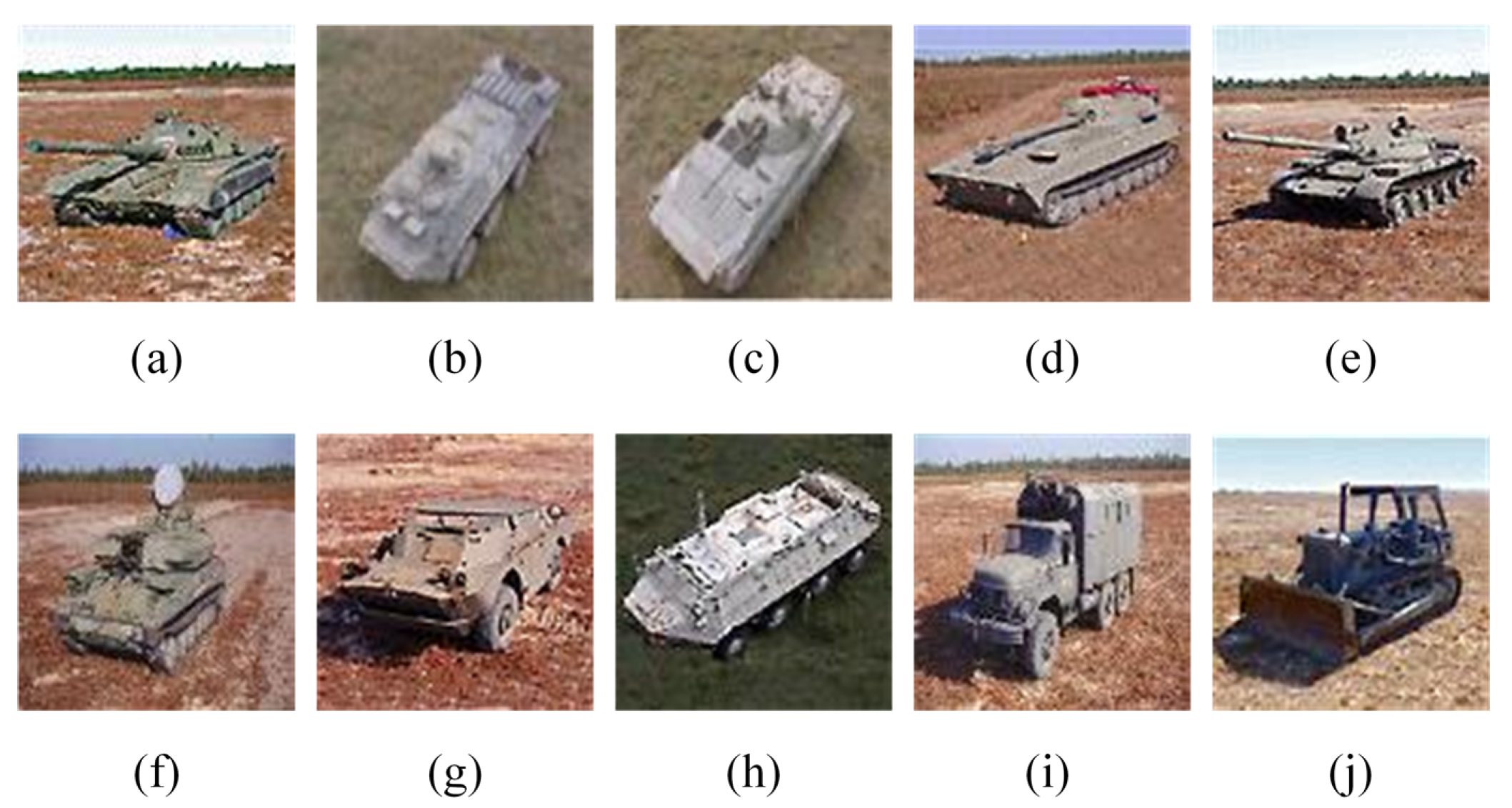

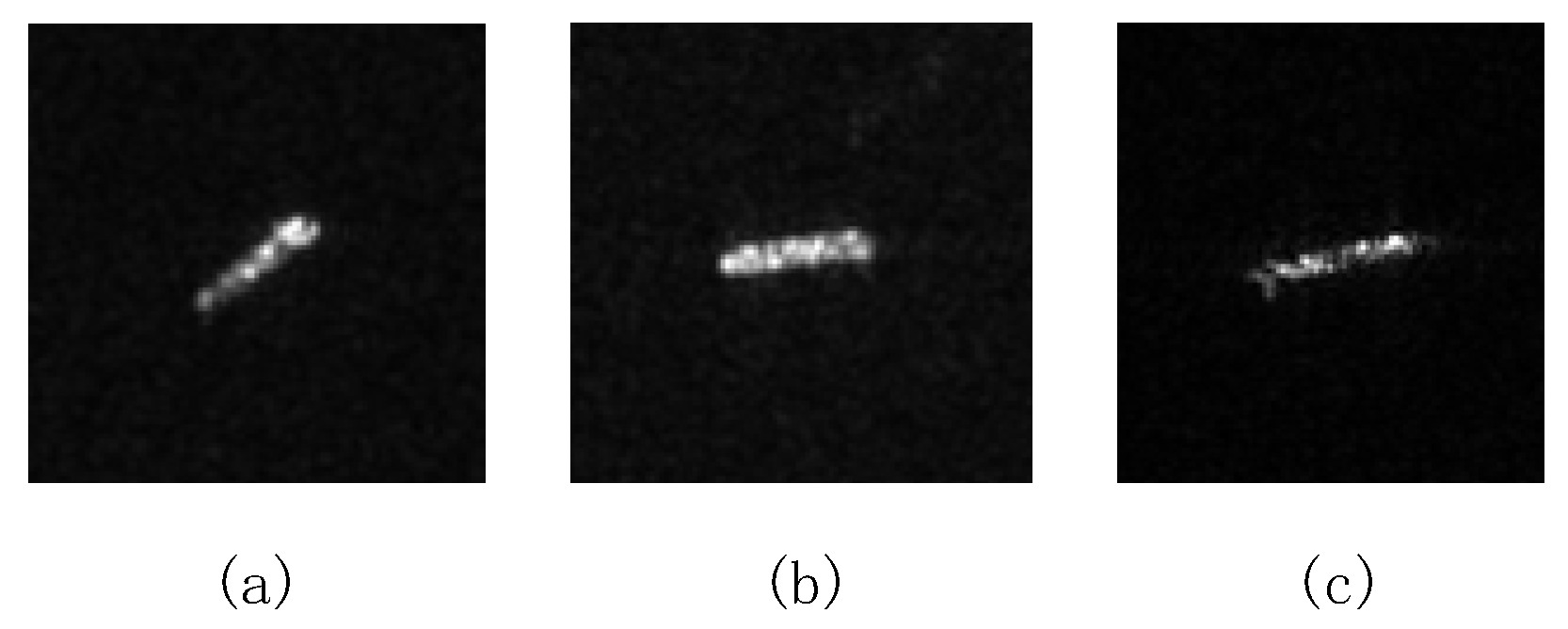

3.1. Datasets and Experimental Parameter Settings

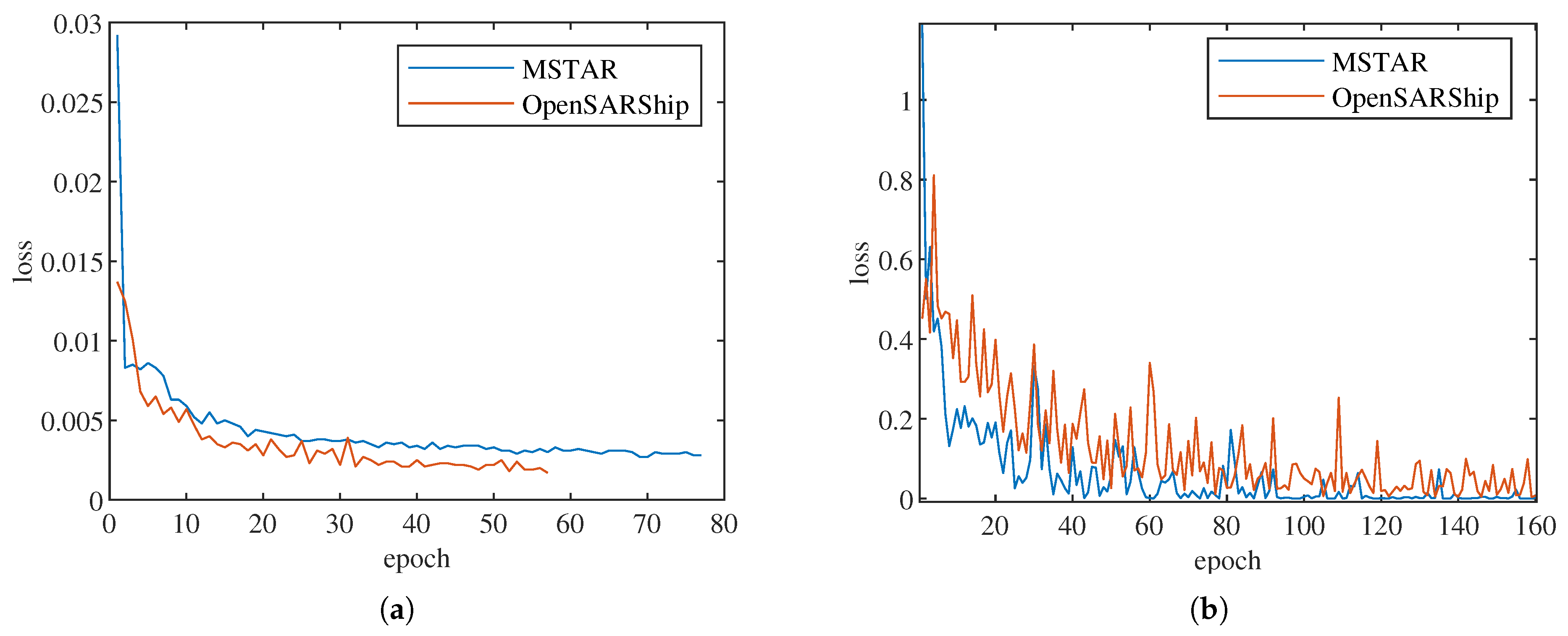

3.2. Experimental Results on Different Datasets

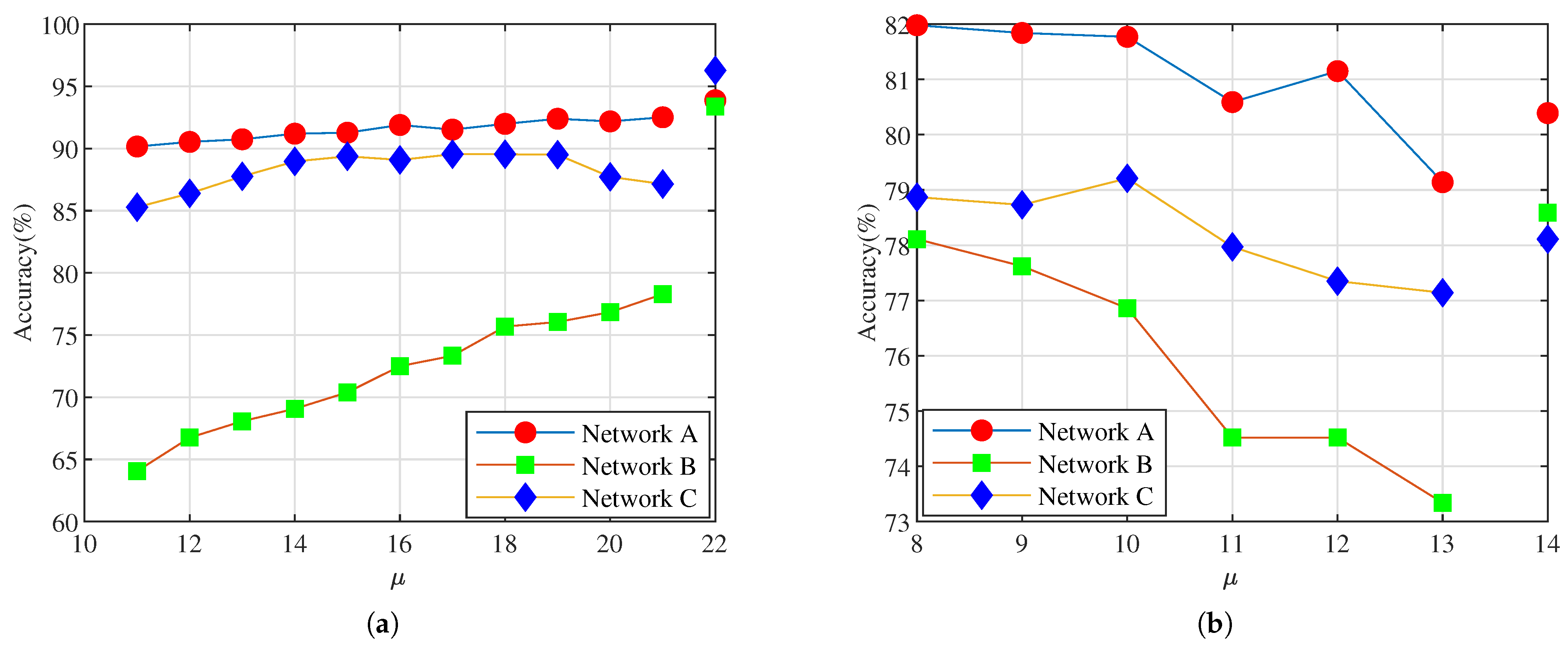

3.3. Ablation Experiments

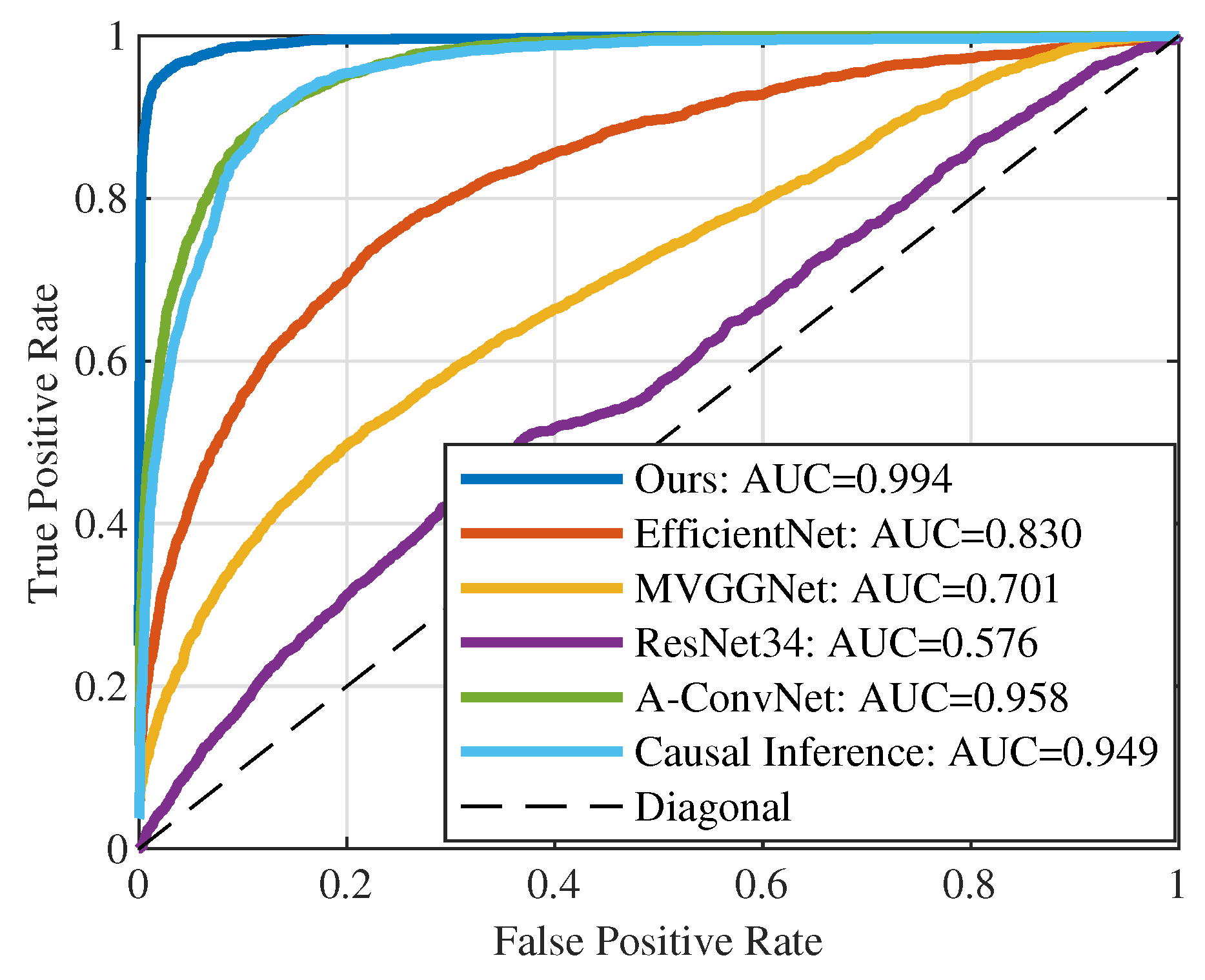

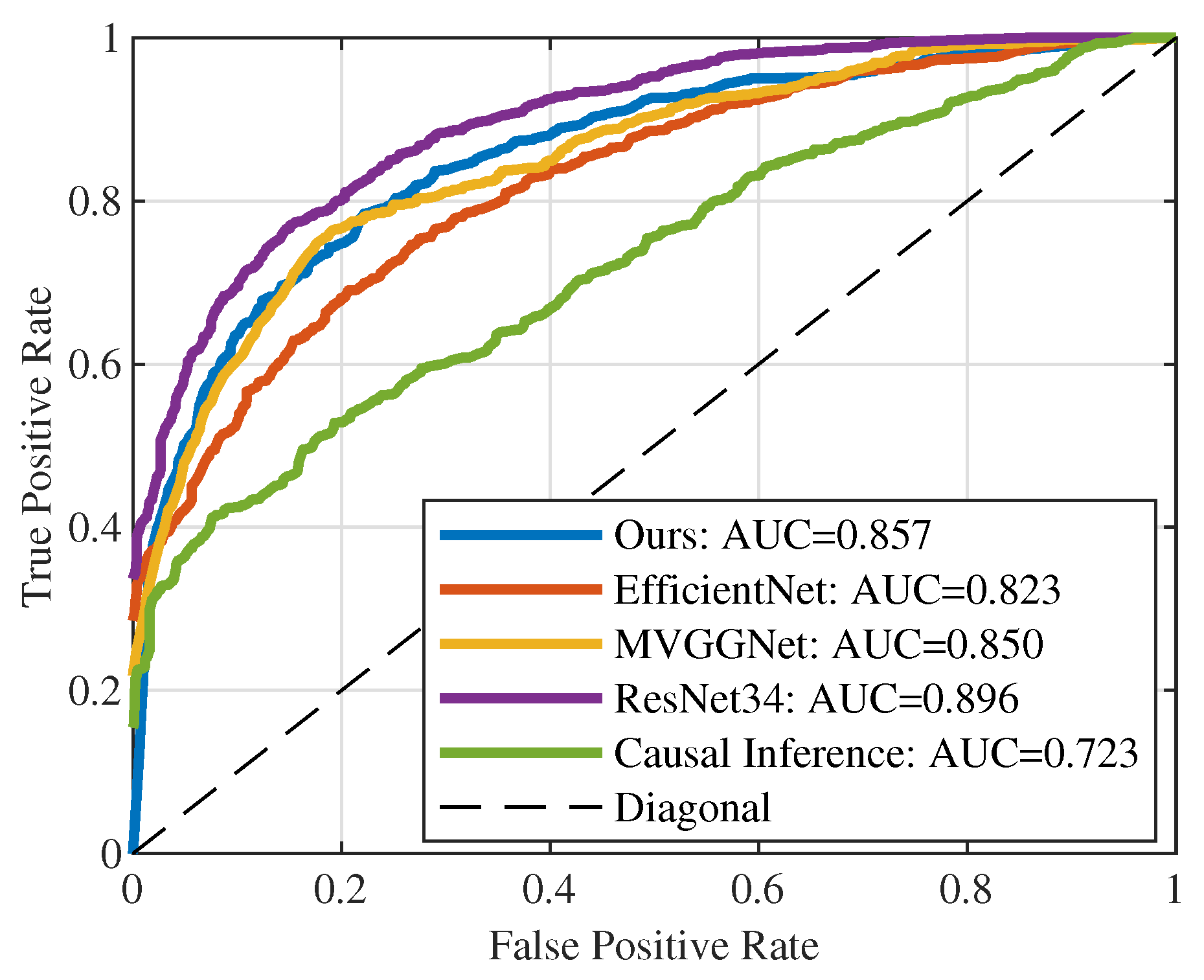

3.4. Comparative Experiments

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moreira, A.; Prats-Iraola, P.; Younis, M.; Krieger, G.; Hajnsek, I.; Papathanassiou, K.P. A tutorial on synthetic aperture radar. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2013, 1, 6–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Yu, H.; Peng, Y.; Miao, L.; Ren, H. Relation-Guided Embedding Transductive Propagation Network with Residual Correction for Few-Shot SAR ATR. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.C.; Liu, Y.; Xiang, J.; Liu, W.; Xing, M.; Chen, J. Spaceborne Synthetic Aperture Radar Imaging Algorithms: An overview. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2022, 10, 161–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Xu, D.; Su, T. A Fast Wavenumber Domain 3-D Near-Field Imaging Algorithm for Cross MIMO Array. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Su, T.; Xu, D.; Pang, G.; Gini, F. A practical approach for calibration of MMW MIMO near-field imaging. Signal Process. 2024, 225, 109634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Du, L.; Wei, D. Multiscale CNN Based on Component Analysis for SAR ATR. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leutenegger, S.; Chli, M.; Siegwart, R.Y. BRISK: Binary robust invariant scalable keypoints. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Computer Vision, Barcelona, Spain, 6–13 November 2011; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 2548–2555. [Google Scholar]

- Dalal, N.; Triggs, B. Histograms of oriented gradients for human detection. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’05), San Diego, CA, USA, 20–25 June 2005; Volume 1, pp. 886–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, C.; Pallotta, L.; Gaglione, D.; De Maio, A.; Soraghan, J.J. Automatic Target Recognition of Military Vehicles With Krawtchouk Moments. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2017, 53, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B.; Wen, G.; Zhong, J.; Ma, C.; Yang, X. A robust similarity measure for attributed scattering center sets with application to SAR ATR. Neurocomputing 2017, 219, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K. Validation of PCA and LDA for SAR ATR. In Proceedings of the TENCON 2008—2008 IEEE Region 10 Conference, Hyderabad, India, 19–21 November 2008; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyvärinen, A.; Karhunen, J.; Oja, E. Independent Component Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.M.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Q. Extraction of Sea Ice Cover by Sentinel-1 SAR Based on Support Vector Machine With Unsupervised Generation of Training Data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 3040–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Song, W.; Fang, L.; Chen, Y.; Ghamisi, P.; Benediktsson, J.A. Deep Learning for Hyperspectral Image Classification: An Overview. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 57, 6690–6709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yu, Z.; Yu, L.; Cheng, P.; Chen, J.; Chi, C. A Comprehensive Survey on SAR ATR in Deep-Learning Era. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kechagias-Stamatis, O.; Aouf, N. Automatic Target Recognition on Synthetic Aperture Radar Imagery: A Survey. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 2021, 36, 56–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Chen, B.; Liu, H.; Huang, M. Convolutional Neural Network With Data Augmentation for SAR Target Recognition. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2016, 13, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Lei, B.; Ding, C.; Zhang, Y. Synthetic Aperture Radar Image Synthesis by Using Generative Adversarial Nets. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2017, 14, 1111–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Kim, M. PeaceGAN: A GAN-Based Multi-Task Learning Method for SAR Target Image Generation with a Pose Estimator and an Auxiliary Classifier. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, H.; Xu, F.; Jin, Y.Q. Target Classification Using the Deep Convolutional Networks for SAR Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2016, 54, 4806–4817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Ji, K.; Kang, M.; Leng, X.; Zou, H. Deep Convolutional Highway Unit Network for SAR Target Classification With Limited Labeled Training Data. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2017, 14, 1091–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Song, Y.; Huang, J.; An, D.; Chen, L. SAR Target Classification Based on Multiscale Attention Super-Class Network. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 9004–9019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Yu, X.; Zou, L.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, X.; Bruzzone, L. Extended convolutional capsule network with application on SAR automatic target recognition. Signal Process. 2021, 183, 108021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, X. Squeeze-and-Excitation Laplacian Pyramid Network With Dual-Polarization Feature Fusion for Ship Classification in SAR Images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, X. A polarization fusion network with geometric feature embedding for SAR ship classification. Pattern Recognit. 2022, 123, 108365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Huang, Y.; Huo, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Yeo, T.S. SAR Automatic Target Recognition Based on Multiview Deep Learning Framework. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2018, 56, 2196–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Xue, R.; Wang, L.; Zhou, F. Sequence SAR Image Classification Based on Bidirectional Convolution-Recurrent Network. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 57, 9223–9235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, R.; Bai, X.; Zhou, F. Spatial–Temporal Ensemble Convolution for Sequence SAR Target Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 1250–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, B.; Ni, J.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, S.Y.; Liang, J.; Yuan, H.; Zhang, Q. A Multiview Interclass Dissimilarity Feature Fusion SAR Images Recognition Network Within Limited Sample Condition. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 17820–17836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Gu, M.; Zhang, S.; Sheng, W. An Adaptive Multiview SAR Automatic Target Recognition Network Based on Image Attention. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 13634–13645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Su, T.; Xu, D.; Chen, J.; Liang, Y. MIGA-Net: Multi-View Image Information Learning Based on Graph Attention Network for SAR Target Recognition. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 10779–10792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Sun, J.; Han, Z.; Hong, W. SAR Automatic Target Recognition Method Based on Multi-Stream Complex-Valued Networks. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Luo, C.; Ren, P.; Zhang, B. Multiscale Complex-Valued Feature Attention Convolutional Neural Network for SAR Automatic Target Recognition. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 2052–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Wen, Z.; Li, K.; Pan, Q. Multilevel Scattering Center and Deep Feature Fusion Learning Framework for SAR Target Recognition. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, W.; Liu, T.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L. Lightweight Dual-Stream SAR–ATR Framework Based on an Attention Mechanism-Guided Heterogeneous Graph Network. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 537–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Yu, Y.; Wu, Q. Multimodal Discriminative Feature Learning for SAR ATR: A Fusion Framework of Phase History, Scattering Topology, and Image. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Pan, Z.; Lei, B. What, Where, and How to Transfer in SAR Target Recognition Based on Deep CNNs. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 58, 2324–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Du, L.; Du, Y. Semi-Supervised SAR ATR Based on Contrastive Learning and Complementary Label Learning. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloni, C.; Balleri, A.; Aouf, N.; Le Caillec, J.M.; Merlet, T. Explainability of Deep SAR ATR Through Feature Analysis. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2021, 57, 659–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yang, W.; Liu, L.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y. Discovering and Explaining the Noncausality of Deep Learning in SAR ATR. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Mou, L.; Tang, K.; Cao, Z.; Yang, J. Deep Neural Network Explainability Enhancement via Causality-Erasing SHAP Method for SAR Target Recognition. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Guo, J.; Song, B.; Cai, B.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Z. Interpretability for reliable, efficient, and self-cognitive DNNs: From theories to applications. Neurocomputing 2023, 545, 126267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Wang, L.; Bai, X.; Hui, Y. SAR ATR of Ground Vehicles Based on LM-BN-CNN. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2018, 56, 7282–7293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Xie, J.; Peng, B.; Liu, L. Learning Invariant Representation Via Contrastive Feature Alignment for Clutter Robust SAR ATR. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, M. A New Causal Inference Framework for SAR Target Recognition. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2024, 5, 4042–4057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatello, F.; Weissenborn, D.; Unterthiner, T.; Mahendran, A.; Heigold, G.; Uszkoreit, J.; Dosovitskiy, A.; Kipf, T. Object-Centric Learning with Slot Attention. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Virtual, 6–12 December 2020; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 33, pp. 11525–11538. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.u.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All you Need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Ba, J.L.; Kiros, J.R.; Hinton, G.E. Layer normalization. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1607.06450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Khosla, A.; Lapedriza, A.; Oliva, A.; Torralba, A. Learning deep features for discriminative localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2921–2929. [Google Scholar]

- The Air Force Moving and Stationary Target Recognition (MSTAR) Database. Available online: https://www.sdms.afrl.af.mil (accessed on 1 January 2014).

- Huang, L.; Liu, B.; Li, B.; Guo, W.; Yu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, W. OpenSARShip: A Dataset Dedicated to Sentinel-1 Ship Interpretation. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2018, 11, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanghai Jiao Tong University. OpenSAR: Data and Codes. 2023. Available online: https://opensar.sjtu.edu.cn/DataAndCodes.html (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Delving deep into rectifiers: Surpassing human-level performance on imagenet classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1026–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Shapley, L.S. A value for n-person games. In Contributions to the Theory of Games, Volume II; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1953; pp. 307–317. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; PMLR: New York, NY, USA, 2019. Proceedings of Machine Learning Research. Volume 97, pp. 6105–6114. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Xing, M.; Xie, Y. FEC: A Feature Fusion Framework for SAR Target Recognition Based on Electromagnetic Scattering Features and Deep CNN Features. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 2174–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Class | Serial No. | Training Set | Testing Set | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Num. | Depression | Num. | ||

| T72 | SNS7 | 17° | 228 | 15° | 191 |

| BTR-70 | SNc71 | 17° | 233 | 15° | 196 |

| BMP2 | 9563 | 17° | 233 | 15° | 195 |

| BTR-60 | K10yt7532 | 17° | 256 | 15° | 195 |

| 2S1 | b01 | 17° | 299 | 15° | 274 |

| BRDM-2 | E-71 | 17° | 298 | 15° | 274 |

| D7 | 92v13105 | 17° | 299 | 15° | 274 |

| T62 | A51 | 17° | 299 | 15° | 273 |

| ZIL131 | E12 | 17° | 299 | 15° | 274 |

| ZSU-234 | d08 | 17° | 299 | 15° | 274 |

| Class | Training Num. | Testing Num. |

|---|---|---|

| Bulk Carrier | 182 | 1182 |

| Container Ship | 182 | 188 |

| Tanker | 182 | 78 |

| Class | T72 | BTR-70 | BMP2 | BTR-60 | 2S1 | BRDM-2 | D7 | T62 | ZIL131 | ZSU-234 | Acc. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T72 | 191 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 98.45 |

| BTR-70 | 1 | 165 | 5 | 9 | 5 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 85.05 |

| BMP2 | 13 | 0 | 172 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 88.66 |

| BTR-60 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 174 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 90.16 |

| 2S1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 266 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 97.08 |

| BRDM-2 | 3 | 11 | 8 | 10 | 2 | 240 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 87.59 |

| D7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 273 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 99.64 |

| T62 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 261 | 8 | 2 | 95.60 |

| ZIL131 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 264 | 2 | 96.35 |

| ZSU-234 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 264 | 96.35 |

| Total | 93.88 | ||||||||||

| Class | Bulk Carrier | Container Ship | Tanker | Acc. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk Carrier | 947 | 228 | 7 | 80.12 |

| Container Ship | 46 | 141 | 1 | 75.00 |

| Tanker | 1 | 1 | 76 | 97.44 |

| Total | 80.39 | |||

| Shapley Value | Network | A | B | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Player | ||||

| MSTAR | Background | 0.0083 | 0.07 | 0.0131 |

| Target | 0.9917 | 0.93 | 0.9869 | |

| OpenSARShip | Background | 0.0709 | 0.1265 | 0.19 |

| Target | 0.9291 | 0.8735 | 0.81 |

| Network | Network Size | MSTAR | OpenSARShip | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SvB | SvT | SvB | SvT | ||

| EfficientNet [56] | 4.02 M | 0.4695 | 0.5305 | 0.4590 | 0.5410 |

| MVGGNet [57] | 16.81 M | 0.4060 | 0.5940 | 0.2798 | 0.7202 |

| ResNet_34 [58] | 21.29 M | 0.2001 | 0.7999 | 0.2547 | 0.7453 |

| A-ConvNet [20] | 0.30 M | 0.1223 | 0.8777 | / | / |

| Causal [45] | 0.32 M | −0.0104 | 0.9896 | −0.0174 | 0.9826 |

| Ours | 1.03 M | 0.0083 | 0.9917 | 0.0709 | 0.9291 |

| Ours (88 × 88) | 0.94 M | 0.0085 | 0.9915 | / | / |

| Ours (60 × 60) | 0.83 M | 0.0055 | 0.9945 | / | / |

| Network | Acc. (%) in MSTAR | Acc. (%) in OpenSARShip | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | New | Original | New | |

| EfficientNet [56] | 97.68% | 42.85% | 83.84% | 79.01% |

| MVGGNet [57] | 99.26% | 8.19% | 85.70% | 63.26% |

| ResNet_34 [58] | 95.45% | 15.22% | 80.66% | 76.73% |

| A-ConvNet [20] | 93.55% | 64.19% | / | / |

| Causal [45] | 68.67% | 65.75% | 81.11% | 79.93% |

| Ours | 93.88% | 91.98% | 80.39% | 81.98% |

| Ours (88 × 88) | 93.87% | 92.27% | / | / |

| Ours (60 × 60) | 94.17% | 92.39% | / | / |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, R.; Su, T.; Liang, Y.; Liu, J. Feature Disentanglement Based on Dual-Mask-Guided Slot Attention for SAR ATR Across Backgrounds. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010003

Wang R, Su T, Liang Y, Liu J. Feature Disentanglement Based on Dual-Mask-Guided Slot Attention for SAR ATR Across Backgrounds. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Ruiqiu, Tao Su, Yuan Liang, and Jiangtao Liu. 2026. "Feature Disentanglement Based on Dual-Mask-Guided Slot Attention for SAR ATR Across Backgrounds" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010003

APA StyleWang, R., Su, T., Liang, Y., & Liu, J. (2026). Feature Disentanglement Based on Dual-Mask-Guided Slot Attention for SAR ATR Across Backgrounds. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010003