Performance Assessment of Satellite-Based Rainfall Products in the Abbay Basin, Ethiopia

Highlights

- In the Gojjam sub-basins, satellite rainfall products capture broad rainfall patterns but exhibit distinct strengths and limitations.

- These products consistently overestimate light rainfall and underestimate heavy rainfall, with systematic errors becoming more dominant as intensity increases.

- Product-specific calibration is required to correct characteristic biases, particularly reducing missed light rainfall in CHIRPS and false alarms in MSWEP/TAMSAT.

- Sub-basin scale evaluation underscores the importance of localized calibration for reliable hydrological modeling and climate assessments in Ethiopia’s complex highland terrain.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.1.1. Location and Elevation

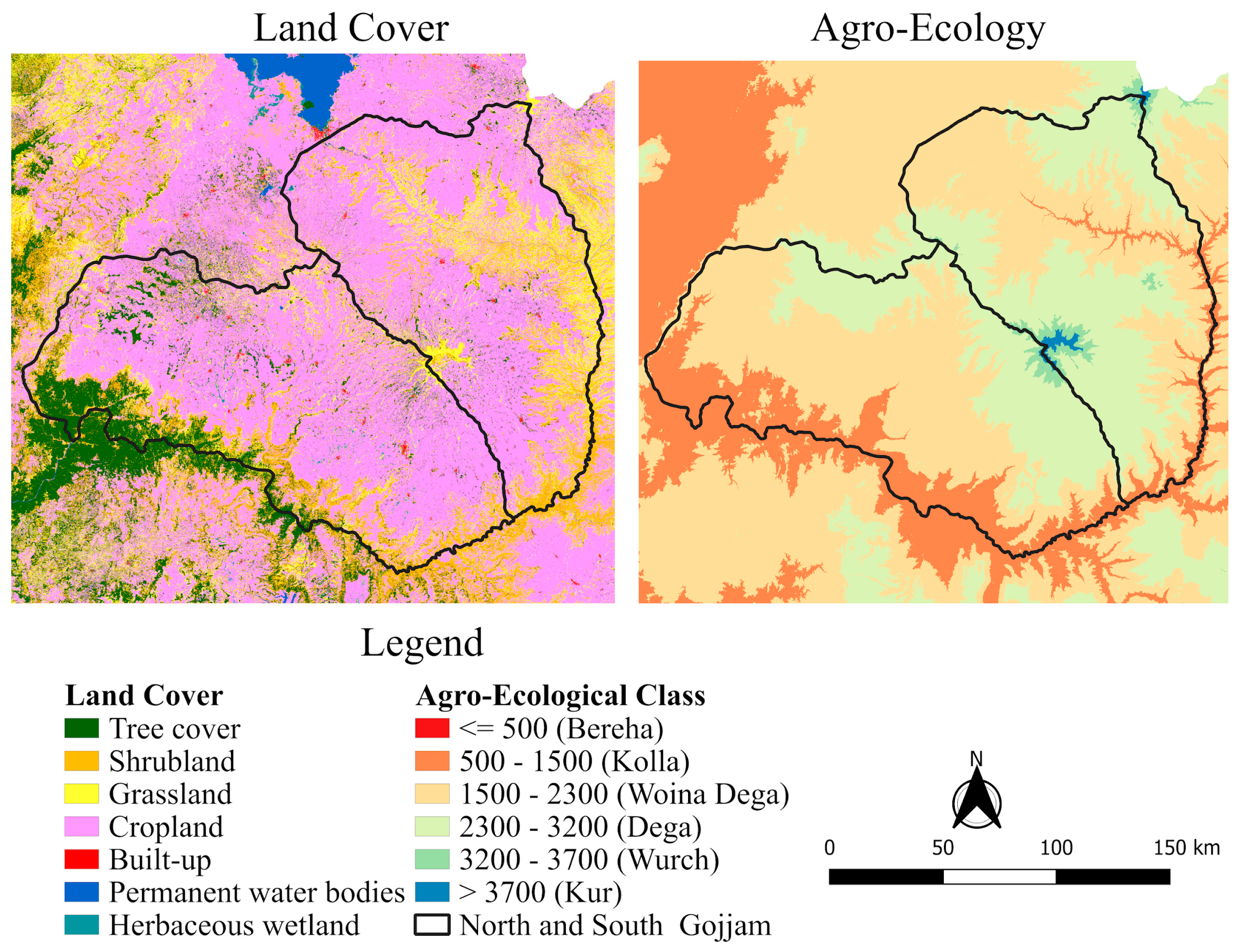

2.1.2. Rainfall, Land Use and Agro-Ecology

2.2. Data Sources

2.2.1. Ground Station Data

Data Quality Control and Processing

2.2.2. Satellite Rainfall Products (SRPs)

TAMSAT v3.1

CHIRPS v2.0

MSWEP v2.8

2.3. SRPs Performance Validation and Metrics

2.4. Distribution of Rainfall Frequency and Intensity Categories

2.5. Application of Bias Decomposition in Satellite Rainfall Estimates

- Error component decomposition

- 2.

- Mean square error decomposition

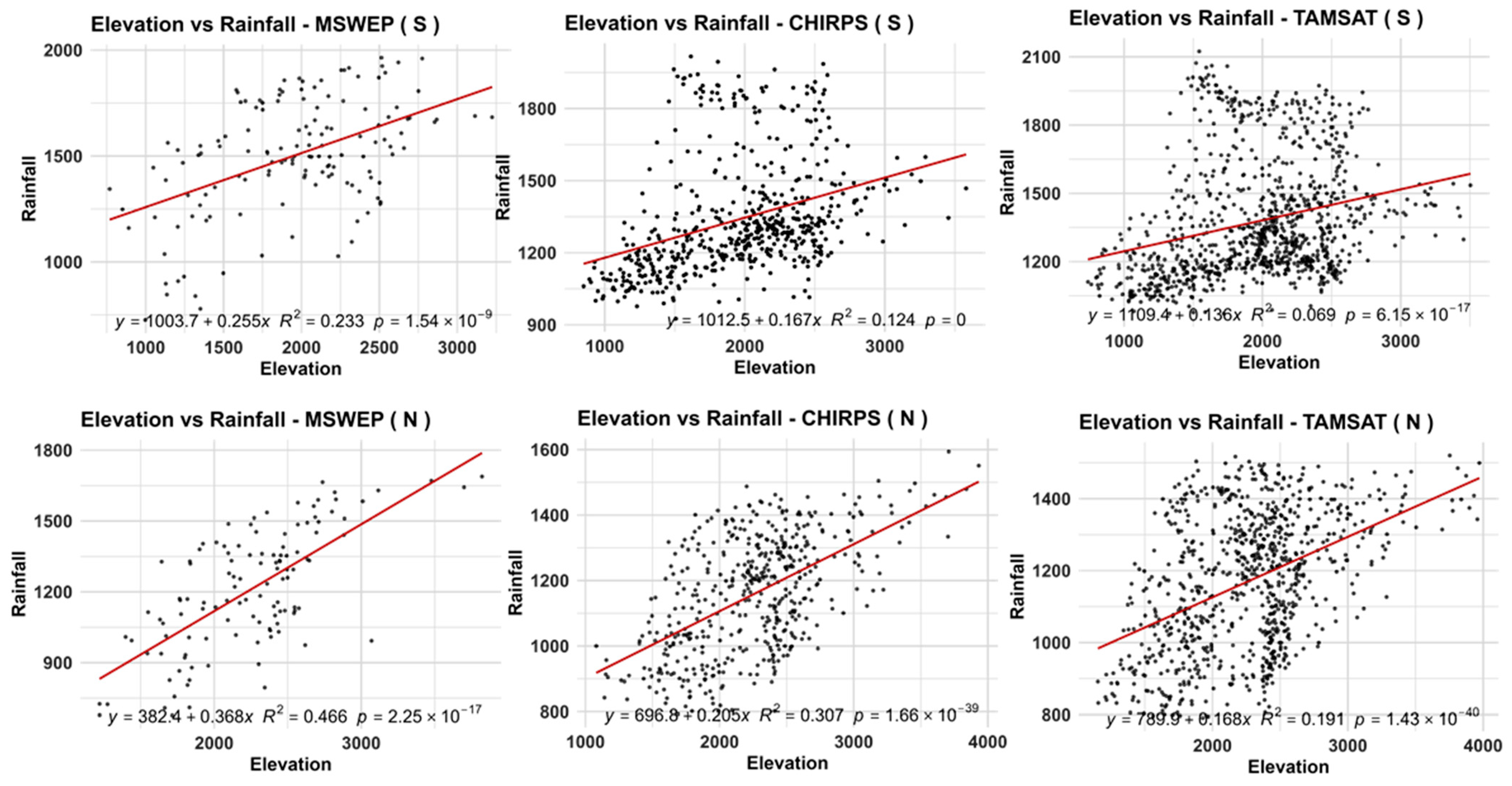

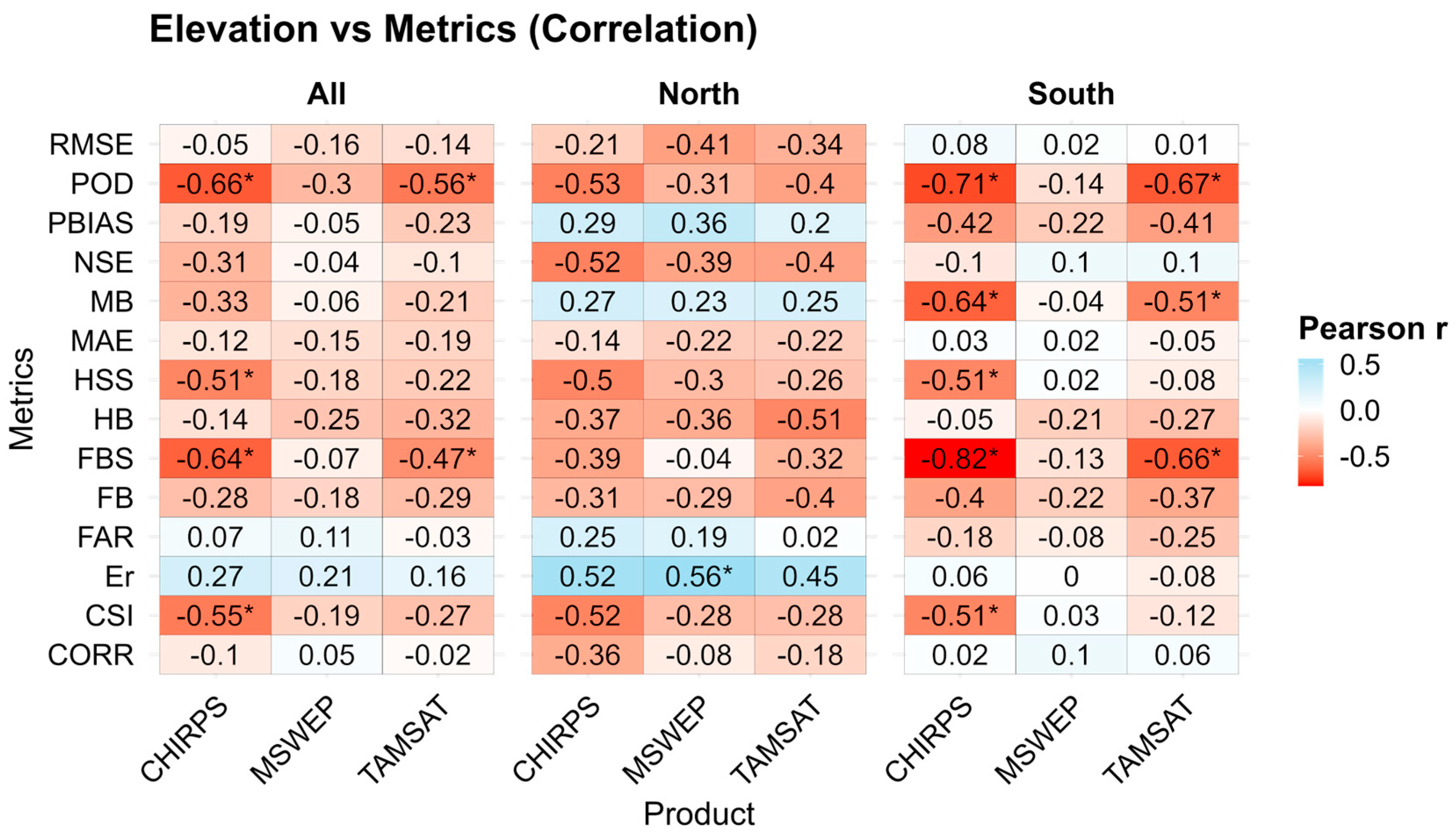

2.6. Elevation-Dependent Variations

2.7. Comparative Statistical Testing of Satellite Rainfall Products

- Bootstrap CIs: For product pair differences, using percentile bounds (2.5th–97.5th) from resampling.

- T-based CIs: For individual metrics (e.g., RMSE, R2, and POD) based on Student’s t-distribution.

- (H_0): Mean difference = 0 (no difference)

- (H_1): Mean difference ≠ 0 (products differ)

- (H_0): Metrics equal/same distribution across regions

- (H_1): Metrics differ across regions

3. Results and Discussion

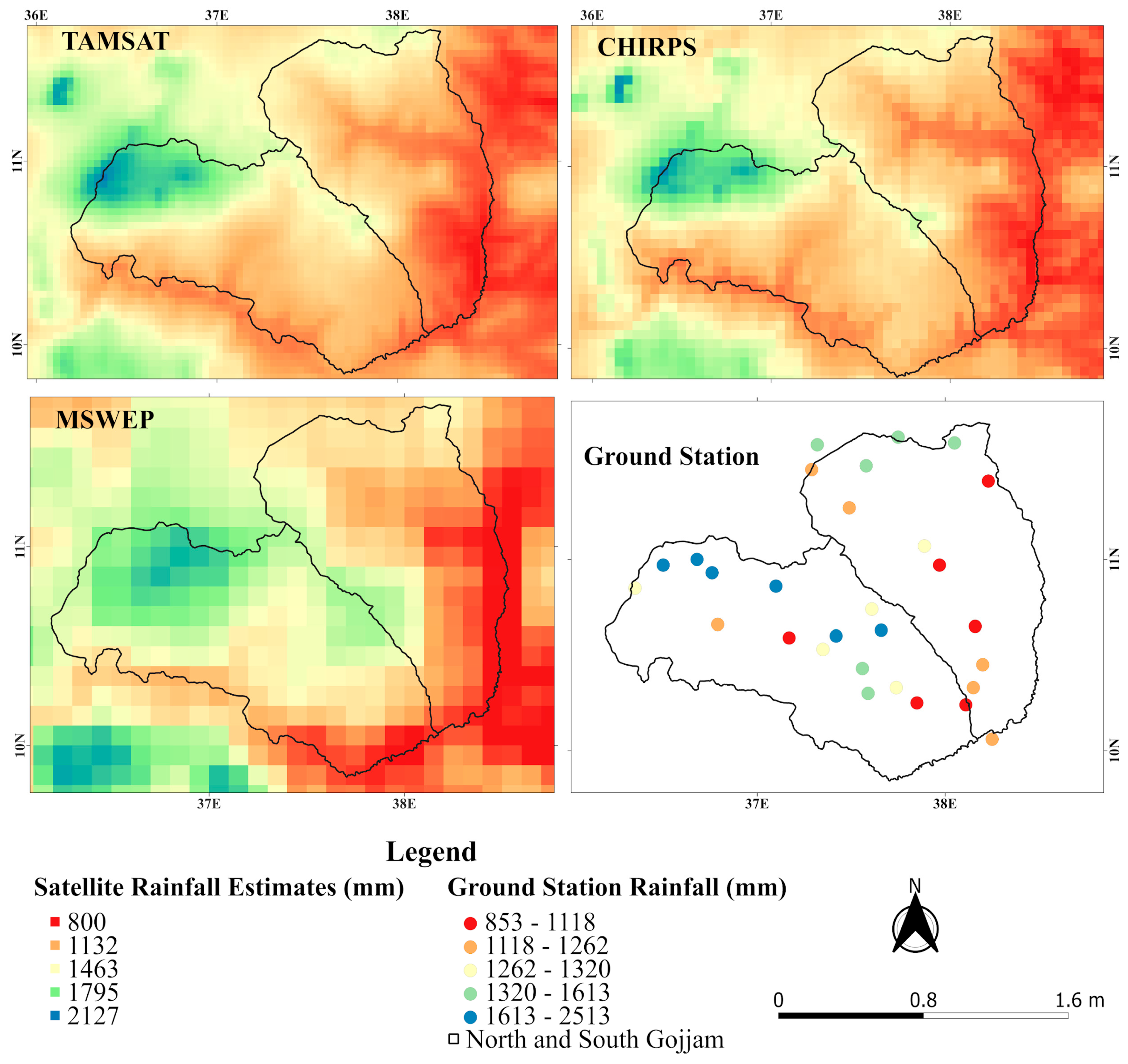

3.1. Spatial Comparison and Annual Bias of SRPs

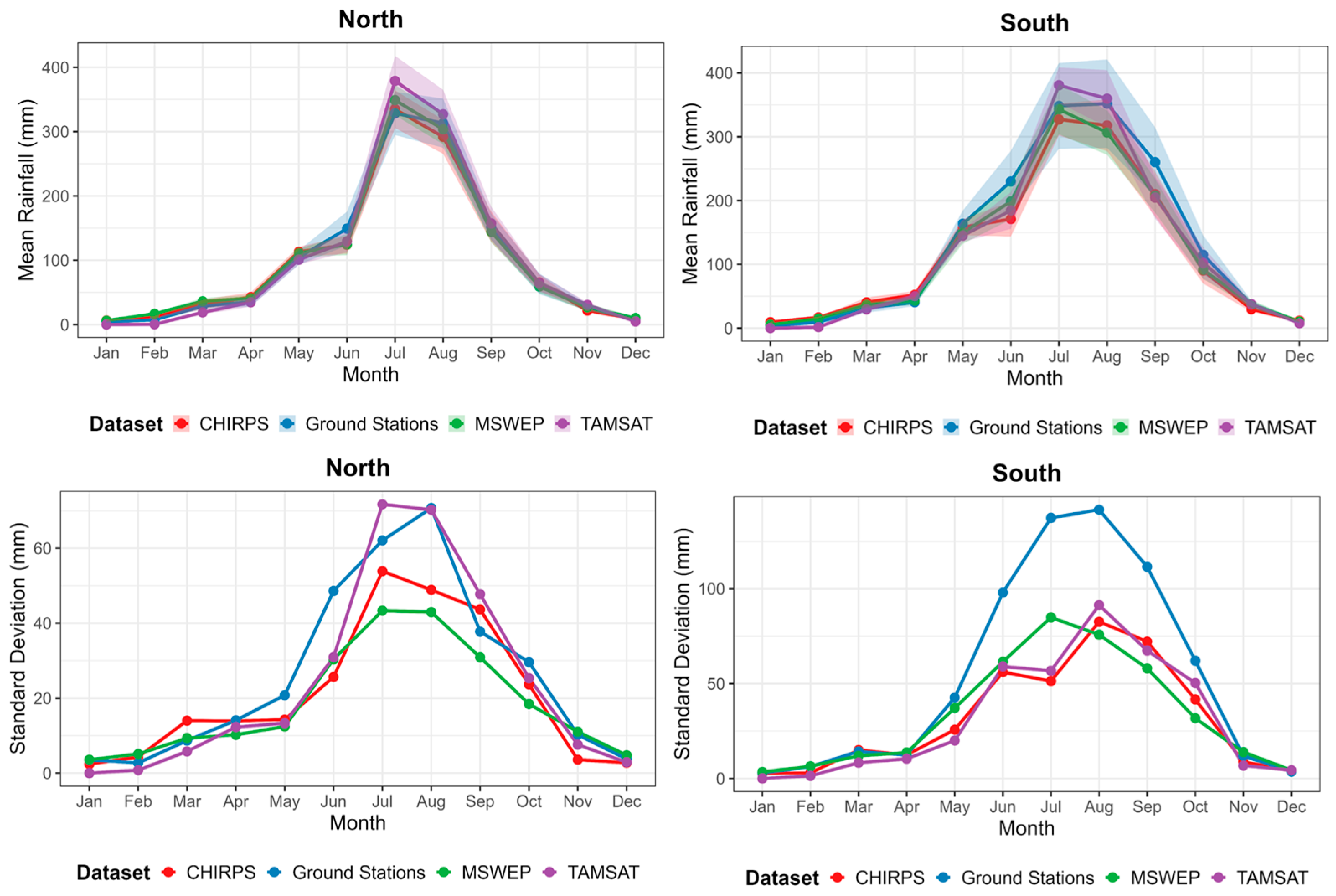

3.2. Performance of SRPs in Capturing and Representing Rainfall Variability

3.3. Rainfall Total Detection Capability

3.4. Rainfall Occurrence Detection Capability

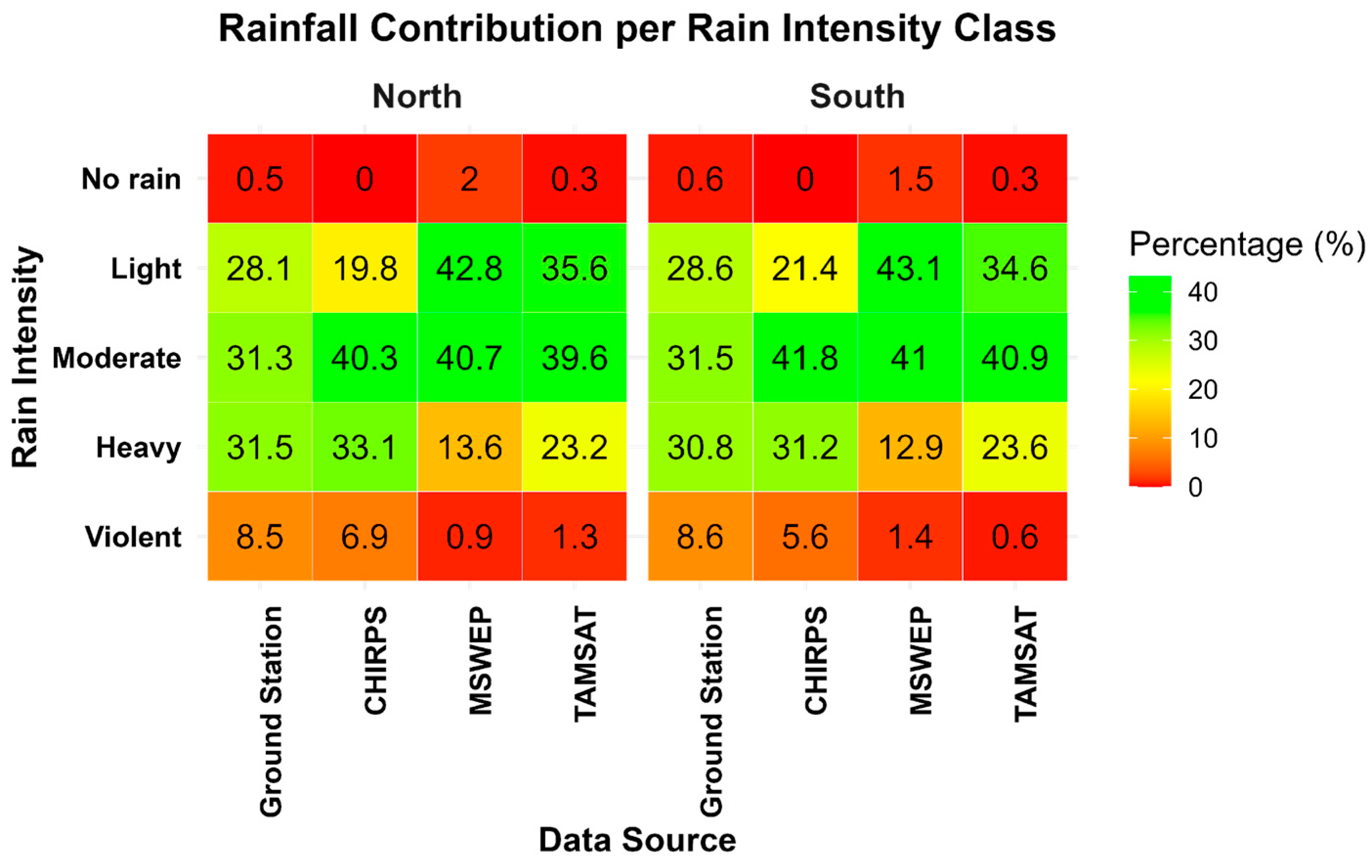

3.5. Rainfall Intensity and Frequency Representation for SRPs

3.6. Observed Bias Components and Error Patterns in Satellite Rainfall Estimates

3.7. Bias (Error) Decomposition Across Rainfall Intensity Categories

3.8. Elevation Dependent Variations in the Detection and Accuracy of SRPs

3.9. Monthly and Seasonal Total Rainfall Performance

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gebremicael, T.G.; Mohamed, Y.A.; Zaag, P.V.; Hagos, E.Y. Temporal and spatial changes of rainfall and streamflow in the Upper Tekezē–Atbara river basin, Ethiopia. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 21, 2127–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, V.; Oliveira, R.J.; Datok, P.; Sauvage, S.; Paris, A.; Gosset, M.; Sánchez-Pérez, J. Evaluating the performance of multiple satellite-based precipitation products in the Congo River Basin using the SWAT model. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2022, 42, 101168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tola, F.T.; Dadi, D.K.; Kenea, T.T.; Dinku, T. Weather and climate services in Ethiopia: Progress, challenges, and opportunities. Front. Clim. 2025, 7, 1551188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Tang, G.; Ma, Y.; Huang, Q.; Han, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, C.; Guo, X. Remote Sensing Precipitation: Sensors, Retrievals, Validations, and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abera, W.; Brocca, L.; Rigon, R. Comparative evaluation of different satellite rainfall estimation products and bias correction in the Upper Blue Nile (UBN) basin. Atmos. Res. 2016, 178–179, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremichael, M.; Anagnostou, E.N.; Bitew, M.M. Critical Steps for Continuing Advancement of Satellite Rainfall Applications for Surface Hydrology in the Nile River Basin. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2010, 46, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinku, T.; Ceccato, P.; Grover-Kopec, E.; Lemma, M.; Connor, S.J.; Ropelewski, C.F. Validation of satellite rainfall products over East Africa’s complex topography. Int. J. Remote. Sens. 2007, 28, 1503–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.S.; Indu, J. Performance Assessment of Multi-Source Weighted-Ensemble Precipitation (MSWEP) Product over India. Climate 2017, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alijanian, M.; Rakhshandehroo, G.R.; Mishra, A.K.; Dehghani, M. Evaluation of satellite rainfall climatology using CMORPH, PERSIANN-CDR, PERSIANN, TRMM, MSWEP over Iran. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 4896–4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Chen, Y.; Azmat, M.; Kayumba, P.M.; Ahmed, Z.; Mind’je, R.; Ghaffar, A.; Qin, J.; Tariq, A. Long-Term Performance Evaluation of the Latest Multi-Source Weighted-Ensemble Precipitation (MSWEP) over the Highlands of Indo-Pak (1981–2009). Remote. Sens. 2022, 14, 4773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Sharma, P.J.; Teegavarapu, R.S. Rain event detection and magnitude estimation during Indian summer monsoon: Comprehensive assessment of gridded precipitation datasets across hydroclimatically diverse regions. Atmos. Res. 2025, 313, 107761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Falahi, A.H.; Saddique, N.; Spank, U.; Gebrechorkos, S.H.; Bernhofer, C. Evaluation the Performance of Several Gridded Precipitation Products over the Highland Region of Yemen for Water Resources Management. Remote. Sens. 2020, 12, 2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.Y.; Aryastana, P.; Liu, G.R.; Huang, W.R. Assessment of satellite precipitation product estimates over Bali Island. Atmos. Res. 2020, 244, 105032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Bigiarini, M.; Nauditt, A.; Birkel, C.; Verbist, K.; Ribbe, L. Temporal and spatial evaluation of satellite-based rainfall estimates across the complex topographical and climatic gradients of Chile. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 21, 1295–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Zhao, W.; Li, C.; Liu, Y. Evaluation of Six Satellite and Reanalysis Precipitation Products Using Gauge Observations over the Yellow River Basin, China. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, R.; Silwal, P.; Duwal, S.; Shrestha, S.; Kafle, A.S.; Talchabhadel, R.; Kumar, S. Detectability of rainfall characteristics over a mountain river basin in the Himalayan region from 2000 to 2015 using ground- and satellite-based products. Theor. Appl. Clim. 2021, 147, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembélé, M.; Zwart, S.J. Evaluation and comparison of satellite-based rainfall products in Burkina Faso, West Africa. Int. J. Remote. Sens. 2016, 37, 3995–4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garba, J.N.; Diasso, U.J.; Waongo, M.; Sawadogo, W.; Daho, T. Performance evaluation of satellite-based rainfall estimation across climatic zones in Burkina Faso. Theor. Appl. Clim. 2023, 154, 1051–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattani, E.; Ferguglia, O.; Merino, A.; Levizzani, V. Precipitation Products’ Inter–Comparison over East and Southern Africa 1983–2017. Remote. Sens. 2021, 13, 4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, K.; Velpuri, N.M.; Leh, M.; Akpoti, K.; Owusu, A.; Tinonetsana, P.; Hamouda, T.; Ghansah, B.; Paranamana, T.P.; Munzimi, Y. Accuracy of satellite and reanalysis rainfall estimates over Africa: A multi-scale assessment of eight products for continental applications. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2023, 49, 101514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ageet, S.; Fink, A.H.; Maranan, M.; Diem, J.E.; Hartter, J.; Ssali, A.L.; Ayabagabo, P. Validation of Satellite Rainfall Estimates over Equatorial East Africa. J. Hydrometeorol. 2022, 23, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salami, A.A.; Olanrewaju, R.M.; Olorunfemi, J.F. Performance assessment of satellite rainfall estimates in rain detection capabilities at different thresholds over Nigeria. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2024, 69, 1997–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khettouch, A.; Hssaisoune, M.; Hermans, T.; Aouijil, A.; Bouchaou, L. Ground validation of satellite-based precipitation estimates over poorly gauged catchment: The case of the Drâa basin in Central-East Morocco. Mediterr. Geosci. Rev. 2023, 5, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taye, M.; Mengistu, D.; Sahlu, D. Performance evaluation of multiple satellite rainfall data sets in central highlands of Abbay Basin, Ethiopia. Eur. J. Remote. Sens. 2023, 56, 2233686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addisu, S.; Aniley, E.; Gashaw, T.; Kelemu, S.; Demessie, S.F. Evaluating the performances of gridded satellite products in simulating the rainfall characteristics of Abay Basin, Ethiopia. Sustain. Environ. 2024, 10, 2381349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayehu, G.T.; Tadesse, T.; Gessesse, B.; Dinku, T. Validation of new satellite rainfall products over the Upper Blue Nile Basin, Ethiopia. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2018, 11, 1921–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, S.A.; Qin, T.; Yan, D.; Gelaw, E.B.; Workneh, H.T.; Kun, W.; Liu, S.; Dong, B. Spatial and Temporal Evaluation of the Latest High-Resolution Precipitation Products over the Upper Blue Nile River Basin, Ethiopia. Water 2020, 12, 3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenta, A.A.; Yasuda, H.; Shimizu, K.; Ibaraki, Y.; Haregeweyn, N.; Kawai, T.; Belay, A.S.; Sultan, D.; Ebabu, K. Evaluation of satellite rainfall estimates over the Lake Tana basin at the source region of the Blue Nile River. Atmos. Res. 2018, 212, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, M.M.; Bawoke, G.T. Analysis of spatial variability and temporal trends of rainfall in Amhara region, Ethiopia. J. Water Clim. Chang. 2019, 11, 1505–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayehu, G.T.; Tadesse, T.; Gessesse, B. Spatial and temporal trends and variability of rainfall using long-term satellite product over the Upper Blue Nile Basin in Ethiopia. Remote Sens. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 4, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayable, G.; Amare, G.; Alemu, G.; Gashaw, T. Spatiotemporal variability and trends of rainfall and its association with Pacific Ocean Sea surface temperature in West Harerge Zone, Eastern Ethiopia. Environ. Syst. Res. 2021, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, J.A.; Yimam, Z.A. Spatiotemporal variability and trend analysis of rainfall in Beshilo sub-basin, Upper Blue Nile (Abbay) Basin of Ethiopia. Arab. J. Geosci. 2022, 15, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewket, W.; Tibebe, D.; Teferi, E.; Degefu, M.A. Changes in mean and extreme rainfall indices over a problemscape in central Ethiopia. Environ. Chall. 2024, 15, 100883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiemig, V.; Rojas, R.; Zambrano-Bigiarini, M.; De Roo, A. Hydrological evaluation of satellite-based rainfall estimates over the Volta and Baro-Akobo Basin. J. Hydrol. 2013, 499, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoche, M.; Fischer, C.; Pohl, E.; Krause, P.; Merz, R. Combined uncertainty of hydrological model complexity and satellite-based forcing data evaluated in two data-scarce semi-arid catchments in Ethiopia. J. Hydrol. 2014, 519, 2049–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.C.; Getirana, A.; Policelli, F.; McNally, A.; Arsenault, K.R.; Kumar, S.; Tadesse, T.; Peters-Lidard, C.D. Upper Blue Nile basin water budget from a multi-model perspective. J. Hydrol. 2017, 555, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alato, A.A. Satellite Based Rainfall and Potential Evaporation for Streamflow Simulation and Water Balance Assessment: A case Study in Wabi Watershed, Ethiopia. Master’s Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Z.; Tuo, Y.; Liu, J.; Gao, H.; Song, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, L.; Mekonnen, D.F. Hydrological evaluation of open-access precipitation and air temperature datasets using SWAT in a poorly gauged basin in Ethiopia. J. Hydrol. 2019, 569, 612–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goshime, D.W.; Absi, R.; Haile, A.T.; Ledésert, B.; Rientjes, T. Bias-Corrected CHIRP Satellite Rainfall for Water Level Simulation, Lake Ziway, Ethiopia. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2020, 25, 05020024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.H.; Molla, D.D.; Lohani, T.K. Performance evaluation of satellite-based rainfall estimates for hydrological modeling over Bilate river basin, Ethiopia. World J. Eng. 2022, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayissa, Y.; Tadesse, T.; Demisse, G.; Shiferaw, A. Evaluation of Satellite-Based Rainfall Estimates and Application to Monitor Meteorological Drought for the Upper Blue Nile Basin, Ethiopia. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayissa, Y.A.; Tadesse, T.; Svoboda, M.; Wardlow, B.; Poulsen, C.; Swigart, J.; Van Andel, S.J. Developing a satellite-based combined drought indicator to monitor agricultural drought: A case study for Ethiopia. GIScience Remote Sens. 2019, 56, 718–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfamariam, B.G.; Melgani, F.; Gessesse, B. Rainfall retrieval and drought monitoring skill of satellite rainfall estimates in the Ethiopian Rift Valley Lakes Basin. J. Appl. Remote. Sens. 2019, 13, 014522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taye, M.; Sahlu, D.; Zaitchik, B.F.; Neka, M. Evaluation of Satellite Rainfall Estimates for Meteorological Drought Analysis over the Upper Blue Nile Basin, Ethiopia. Geosciences 2020, 10, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejene, T.; Dalle, G.; Woldeamanuel, T.; Mekuyie, M. Temporal climate conditions and spatial drought patterns across rangelands in pastoral areas of West Guji and Borana zones, Southern Ethiopia. Pastoralism 2023, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalishe, A.; Berihu, T.; Arba, Y. Performance evaluation of multi-satellite rainfall products for analyzing rainfall variability in Abaya–Chamo basin: Southern Ethiopia. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 133, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinku, T.; Funk, C.; Peterson, P.; Maidment, R.; Tadesse, T.; Gadain, H.; Ceccato, P. Validation of the CHIRPS satellite rainfall estimates over eastern Africa. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2018, 144, 292–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malede, D.A.; Agumassie, T.A.; Kosgei, J.R.; Pham, Q.B.; Andualem, T.G. Evaluation of Satellite Rainfall Estimates in a Rugged Topographical Basin Over South Gojjam Basin, Ethiopia. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2022, 50, 1333–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asefw, E.T.; Ayehu, G.T. Validating the Skills of Satellite Rainfall Products and Spatiotemporal Rainfall Variability Analysis over Omo River Basin in Ethiopia. Hydrology 2024, 12, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodebo, D.Y.; Melesse, A.M.; Woldesenbet, T.A.; Mekonnen, K.; Amdihun, A.; Korecha, D.; Tedla, H.Z.; Corzo, G.; Teshome, A. Comprehensive performance evaluation of satellite-based and reanalysis rainfall estimate products in Ethiopia: For drought, flood, and water resources applications. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 57, 102150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romilly, T.G.; Gebremichael, M. Evaluation of satellite rainfall estimates over Ethiopian river basins. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2011, 15, 1505–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilma, A.D.; Awulachew, S.B. Characterization and Atlas of the Blue Nile Basin and Its Sub Basins; International Water Management Institute (IWMI): Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tadesse, M.; Alemu, B.; Bekele, G.; Tebikew, T.; Chamberlin, J.; Benson, T. Atlas of the Ethiopian Rural Economy; International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA; Central Statistical Agency, Ethiopian Development Research Institute: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Maidment, R.I.; Grimes, D.; Black, E.; Tarnavsky, E.; Young, M.; Greatrex, H.; Allan, R.P.; Stein, T.; Nkonde, E.; Senkunda, S.; et al. A new, long-term daily satellite-based rainfall dataset for operational monitoring in Africa. Sci. Data 2017, 4, 170063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, C.; Peterson, P.; Landsfeld, M.; Pedreros, D.; Verdin, J.; Shukla, S.; Husak, G.; Rowland, J.; Harrison, L.; Hoell, A.; et al. The climate hazards infrared precipitation with stations—A new environmental record for monitoring extremes. Sci. Data 2015, 2, 150066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.E.; Wood, E.F.; Pan, M.; Fisher, C.K.; Miralles, D.G.; van Dijk, A.I.J.M.; McVicar, T.R.; Adler, R.F. MSWEP V2 Global 3-Hourly 0.1° Precipitation: Methodology and Quantitative Assessment. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2019, 100, 473–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinku, T.; Alessandrini, S.; Evangelisti, M.; Rojas, O. A description and evaluation of FAO satellite rainfall estimation algorithm. Atmos. Res. 2015, 163, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremicael, T.G.; Mohamed, Y.A.; van der Zaag, P.; Gebremedhin, A.; Gebremeskel, G.; Yazew, E.; Kifle, M. Evaluation of multiple satellite rainfall products over the rugged topography of the Tekeze-Atbara basin in Ethiopia. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2019, 40, 4326–4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniley, E.; Gashaw, T.; Abraham, T.; Demessie, S.F.; Bayabil, H.K.; Worqlul, A.W.; van Oel, P.R.; Dile, Y.T.; Chukalla, A.D.; Haileslassie, A.; et al. Evaluating the performances of gridded satellite/reanalysis products in representing the rainfall climatology of Ethiopia. Geocarto Int. 2023, 38, 2278329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinku, T.; Chidzambwa, S.; Ceccato, P.; Connor, S.J.; Ropelewski, C.F. Validation of high-resolution satellite rainfall products over complex terrain. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2008, 29, 4097–4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belay, A.S.; Fenta, A.A.; Yenehun, A.; Nigate, F.; Tilahun, S.A.; Moges, M.M.; Dessie, M.; Adgo, E.; Nyssen, J.; Chen, M.; et al. Evaluation and Application of Multi-Source Satellite Rainfall Product CHIRPS to Assess Spatio-Temporal Rainfall Variability on Data-Sparse Western Margins of Ethiopian Highlands. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, K.E.; Melesse, A.M.; Abebe, A.; Lakew, H.B.; Paron, P. Evaluation of Global Precipitation Products over Wabi Shebelle River Basin, Ethiopia. Hydrology 2022, 9, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriasi, D.N.; Arnold, J.G.; Van Liew, M.W.; Bingner, R.L.; Harmel, R.D.; Veith, T.L. Model Evaluation Guidelines for Systematic Quantification of Accuracy in Watershed Simulations. Trans. ASABE 2007, 50, 885–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, J.E.; Sutcliffe, J.V. River Flow Forecasting through Conceptual Model. Part 1—A Discussion of Principles. J. Hydrol. 1970, 10, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, K.; Melesse, A.M.; Woldesenbet, T.A. Spatial evaluation of satellite-retrieved extreme rainfall rates in the Upper Awash River Basin, Ethiopia. Atmos. Res. 2021, 249, 105192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremichael, M.; Bitew, M.M.; Hirpa, F.A.; Tesfay, G.N. Accuracy of satellite rainfall estimates in the Blue Nile Basin: Lowland plain versus highland mountain. Water Resour. Res. 2014, 50, 8775–8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemseged, T.H.; Tom, R. Evaluation of regional climate model simulations of rainfall over the Upper Blue Nile basin. Atmos. Res. 2015, 161–162, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Peters-Lidard, C.D.; Eylander, J.B.; Joyce, R.J.; Huffman, G.J.; Adler, R.F.; Hsu, K.; Turk, F.J.; Garcia, M.; Zeng, J. Component analysis of errors in satellite-based precipitation estimates. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2009, 114, D24101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Dhanya, C. An improved error decomposition scheme for satellite-based precipitation products. J. Hydrol. 2021, 598, 126434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Guilloteau, C.; Kirstetter, P.; Foufoula-Georgiou, E. A New Event-Based Error Decomposition Scheme for Satellite Precipitation Products. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, e2023GL105343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yong, B.; Kirstetter, P.E.; Wang, L.; Hong, Y. Global component analysis of errors in three satellite-only global precipitation estimates. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 3087–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, C.J. On the Validation of Models. Phys. Geogr. 1981, 2, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AghaKouchak, A.; Mehran, A.; Norouzi, H.; Behrangi, A. Systematic and random error components in satellite precipitation data sets. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39, L09406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirpa, F.A.; Gebremichael, M.; Hopson, T. Evaluation of High-Resolution Satellite Precipitation Products over Very Complex Terrain in Ethiopia. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2010, 49, 1044–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, B.L. The generalization of ‘student’s’ Problem when several different population varlances are involved. Biometrika 1947, 34, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcoxon, F. Individual Comparisons by Ranking Methods. Biom. Bull. 1945, 1, 80–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B.; Whitney, D.R. On a Test of Whether one of Two Random Variables is Stochastically Larger than the Other. Ann. Math. Stat. 1947, 18, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersha, G.T.; Mekuriaw, A. Evaluation of daily based satellite rainfall estimates for flood monitoring in Gumera Watershed, Amhara region, Ethiopia. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2025, 11, 2433690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremedhin, M.A.; Lubczynski, M.W.; Maathuis, B.H.; Teka, D. Novel approach to integrate daily satellite rainfall with in-situ rainfall, Upper Tekeze Basin, Ethiopia. Atmos. Res. 2021, 248, 105192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haile, A.T.; Yan, F.; Habib, E. Accuracy of the CMORPH satellite-rainfall product over Lake Tana Basin in Eastern Africa. Atmos. Res. 2015, 163, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, H.; Xu, C.Y.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, Q.; Kim, J.S.; Chen, J.; Guo, S. Tracking the error sources of spatiotemporal differences in TRMM accuracy using error decomposition method. Hydrol. Res. 2018, 49, 1960–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adane, G.B.; Hirpa, B.A.; Lim, C.H.; Lee, W.K. Evaluation and Comparison of Satellite-Derived Estimates of Rainfall in the Diverse Climate and Terrain of Central and Northeastern Ethiopia. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.P.; Williams, C.J.R.; Chiu, J.C.; Maidment, R.I.; Chen, S.H. Investigation of Discrepancies in Satellite Rainfall Estimates over Ethiopia. J. Hydrometeorol. 2014, 15, 2347–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Land Use | Tree Cover | Scrubland | Grassland | Cropland | Built-up | Bare/Sparse Vegetation | Permanent Water Bodies | Herbaceous Wetland |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | 5.8% | 15.5% | 16% | 61.5% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.2% | 0% |

| South | 17.7% | 13.1% | 9.1% | 58.8% | 0.5% | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.5% |

| Ground Station (Gs) ≥ 1 mm/Day | Ground Station (Gs) < 1 mm/Day | |

|---|---|---|

| Satellite rainfall (S) ≥ 1 mm/day | Hits (H) | False alarms (FA) |

| Satellite rainfall (S) < 1 mm/day | Misses (M) | Correct negatives (N) |

| Metrics | Formula | Value Range | Interpretation | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rainfall Occurrence | Probability of Detection (POD) | 0 to 1 | 1 (perfect detection) | [28,57] | |

| False Alarm Ratio (FAR) | 0 to 1 | 0 (no false alarms) | [57,58] | ||

| Frequency Bias Score (FBS) | 0 to ∞ | 1 (no bias; forecast frequency equals observed frequency) | [57] | ||

| Critical Success Index (CSI) | 0 to 1 | 1 (perfect forecast) | [59,60] | ||

| Heidke Skill Index (HSI) | −∞ to 1 | 1 (perfect skill), 0 is no skill, negative is worse than random | [57,61] | ||

| Rainfall Totals | Coefficient of Determination (R2) | 0 to 1 | 1 (perfect fit) | [62] | |

| Correlation Coefficient (CORR) | −1 to 1 | 1 (perfect positive correlation) | [26,58] | ||

| Percent Bias (PBIAS) | *100 | −∞ to ∞ | 0 (no bias) | [63] | |

| Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | 0 to ∞ | 0 (perfect accuracy) | [24,58] | ||

| Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | 0 to ∞ | 0 (perfect accuracy) | [24,26] | ||

| Nash–Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) | −∞ to 1 | 1 (perfect prediction), 0 is good as the mean of observations, negative is worse than mean | [64] |

| Statistics | Ground Station | CHIRPS | MSWEP | TAMSAT | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual | Monthly | Daily | Annual | Monthly | Daily | Annual | Monthly | Daily | Annual | Monthly | Daily | |

| MEAN | 1429.4 | 119.1 | 3.9 | 1330.9 | 110.9 | 3.7 | 1386 | 115.5 | 3.8 | 1388.5 | 115.7 | 3.8 |

| STDVE | 454.7 | 37.9 | 1.2 | 274.6 | 22.9 | 0.8 | 236.3 | 19.7 | 0.6 | 300.2 | 25 | 0.8 |

| CV | 32% | 21% | 17% | 22% | ||||||||

| MEAN_N | 1219.9 | 101.7 | 3.3 | 1203 | 100.3 | 3.4 | 1227.8 | 102.3 | 3.4 | 1247 | 103.9 | 3.4 |

| STDVE_N | 183.2 | 15.3 | 0.5 | 159.8 | 13.3 | 0.4 | 168.3 | 14 | 0.5 | 209.8 | 17.5 | 0.6 |

| CV_N | 15% | 13% | 14% | 17% | ||||||||

| MEAN_S | 1599.7 | 133.3 | 4.4 | 1434.7 | 119.6 | 4 | 1514.5 | 126.2 | 4.1 | 1503.4 | 125.3 | 4.1 |

| STDVE_S | 538.7 | 44.9 | 1.5 | 307.7 | 25.6 | 0.9 | 205.6 | 17.1 | 0.6 | 318.7 | 26.6 | 0.9 |

| CV_S | 34% | 21% | 14% | 21% | ||||||||

| Rain Event | (%) | North | South | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRPs | POD | FB | HB | MB | Er | POD | FB | HB | MB | Er | |

| No-Rain | CHIRPS | 89 | 26 | 87 | 22 | ||||||

| MSWEP | 78 | 25 | 76 | 22 | |||||||

| TAMSAT | 83 | 26 | 82 | 21 | |||||||

| Light | CHIRPS | 51 | 28 | 38 | −51 | 94 | 56 | 27 | 42 | −46 | 91 |

| MSWEP | 84 | 57 | 38 | −17 | 84 | 90 | 47 | 48 | −12 | 82 | |

| TAMSAT | 75 | 47 | 39 | −27 | 89 | 81 | 37 | 48 | −21 | 85 | |

| Moderate | CHIRPS | 63 | 34 | −32 | −39 | 80 | 65 | 28 | −35 | −37 | 74 |

| MSWEP | 92 | 24 | −31 | −8 | 64 | 95 | 20 | −31 | −5 | 61 | |

| TAMSAT | 86 | 30 | −28 | −14 | 75 | 89 | 24 | −30 | −13 | 69 | |

| Heavy | CHIRPS | 67 | 24 | −59 | −33 | 31 | 68 | 16 | −61 | −32 | 26 |

| MSWEP | 93 | 6 | −59 | −7 | 18 | 96 | 6 | −58 | −4 | 19 | |

| TAMSAT | 88 | 11 | −57 | −11 | 24 | 91 | 10 | −58 | −9 | 20 | |

| Violent | CHIRPS | 72 | 35 | −77 | 0 | 7 | 73 | 15 | −76 | 0 | 6 |

| MSWEP | 95 | 3 | −75 | 0 | 4 | 94 | 2 | −75 | 0 | 4 | |

| TAMSAT | 88 | 2 | −76 | 0 | 7 | 91 | 1 | −75 | 0 | 4 | |

| Time Scale | Metric | North | South | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHIRPS | MSWEP | TAMSAT | CHIRPS | MSWEP | TAMSAT | ||

| Monthly | R2 | 0.7 (±0.1) | 0.6 (±0.1) | 0.6 (±0.1) | 0.6 (±0.1) | 0.6 (±0.1) | 0.6 (±0.1) |

| MAE | 37.4 (±7) | 39.1 (±5.8) | 42.3 (±6.3) | 51.9 (±15.3) | 50.8 (±12.2) | 56.1 (±12) | |

| NSE | 0.8 (±0.1) | 0.7 (±0.1) | 0.7 (±0.1) | 0.7 (±0.1) | 0.7 (±0.1) | 0.6 (±0.1) | |

| PBIAS | −0.1 (±8.9) | 2.4 (±11.3) | 3 (±9.1) | −4.4 (±13.3) | 2 (±14.2) | 0.1 (±14) | |

| RMSE | 62.4 (±14.2) | 65 (±11.5) | 72.1 (±12.2) | 84.8 (±26.9) | 83.8 (±22.4) | 92.9 (±21.5) | |

| JJAS | R2 | 0.5 (±0.1) | 0.5 (±0.1) | 0.4 (±0.1) | 0.3 (±0.1) | 0.3 (±0.1) | 0.2 (±0.1) |

| MAE | 73.2 (±16.2) | 76.2 (±13) | 86.2 (±15.2) | 108.3 (±40) | 105.4 (±31.9) | 119.2 (±31.6) | |

| NSE | 0.4 (±0.2) | 0.4 (±0.2) | 0.2 (±0.2) | −0.8 (±0.7) | −0.9 (±0.8) | −1.4 (±0.9) | |

| PBIAS | −2.4 (±10.6) | 0.5 (±12.5) | 6.8 (±12) | −5.8 (±15.7) | 2.8 (±16.3) | 3.4 (±16.6) | |

| RMSE | 97.9 (±23.5) | 101.9 (±19) | 114.7 (±20.2) | 136.1 (±46.5) | 133.1 (±39.1) | 149.4 (±37.3) | |

| MAM | R2 | 0.5 (±0.1) | 0.5 (±0.1) | 0.5 (±0.1) | 0.7 (±0.1) | 0.6 (±0.1) | 0.5 (±0.1) |

| MAE | 28.1 (±6.6) | 29.4 (±6.1) | 29.9 (±6.6) | 31.8 (±5.5) | 31.7 (±4.9) | 36.3 (±6.1) | |

| NSE | 0.5 (±0.1) | 0.5 (±0.2) | 0.5 (±0.1) | 0.7 (±0.1) | 0.6 (±0.2) | 0.6 (±0.2) | |

| PBIAS | 14.9 (±13.3) | 17.1 (±18.2) | −4.5 (±13.8) | 8.9 (±8) | 4.8 (±9.9) | −1.9 (±8.4) | |

| RMSE | 41.1 (±12.7) | 42.3 (±11.2) | 42.8 (±12.5) | 44.1 (±9.6) | 45.7 (±8.5) | 51.4 (±9.5) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gashaw, T.T.; Melesse, A.M.; Abate, B. Performance Assessment of Satellite-Based Rainfall Products in the Abbay Basin, Ethiopia. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010002

Gashaw TT, Melesse AM, Abate B. Performance Assessment of Satellite-Based Rainfall Products in the Abbay Basin, Ethiopia. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleGashaw, Tadela Terefe, Assefa M. Melesse, and Brook Abate. 2026. "Performance Assessment of Satellite-Based Rainfall Products in the Abbay Basin, Ethiopia" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010002

APA StyleGashaw, T. T., Melesse, A. M., & Abate, B. (2026). Performance Assessment of Satellite-Based Rainfall Products in the Abbay Basin, Ethiopia. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010002