Robust ISAR Autofocus for Maneuvering Ships Using Centerline-Driven Adaptive Partitioning and Resampling

Highlights

- Centerline-driven adaptive partitioning maximizes rotational center separation for accurate phase error estimation under complex 3D ship attitudes.

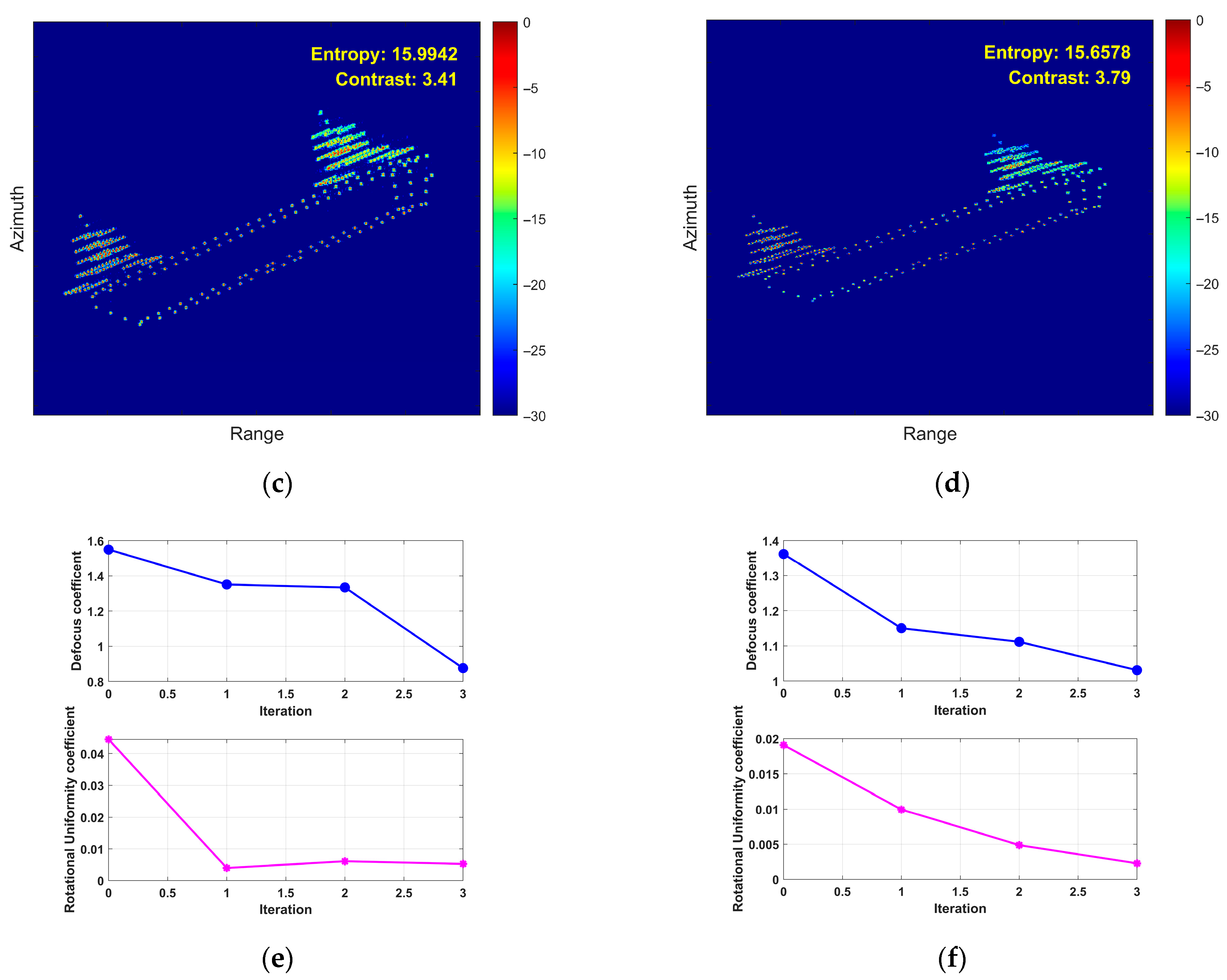

- Novel Rotational Uniformity Coefficient β provides a physically meaningful convergence criterion directly aligned with actual image focus quality.

- Effectively addresses defocusing caused by non-uniform ship rotation, significantly enhancing ship recognition performance in maritime surveillance.

- Maintains identical computational complexity to conventional IPGRA while ensuring robust convergence across various motion scenarios for real-time operational capability.

Abstract

1. Introduction

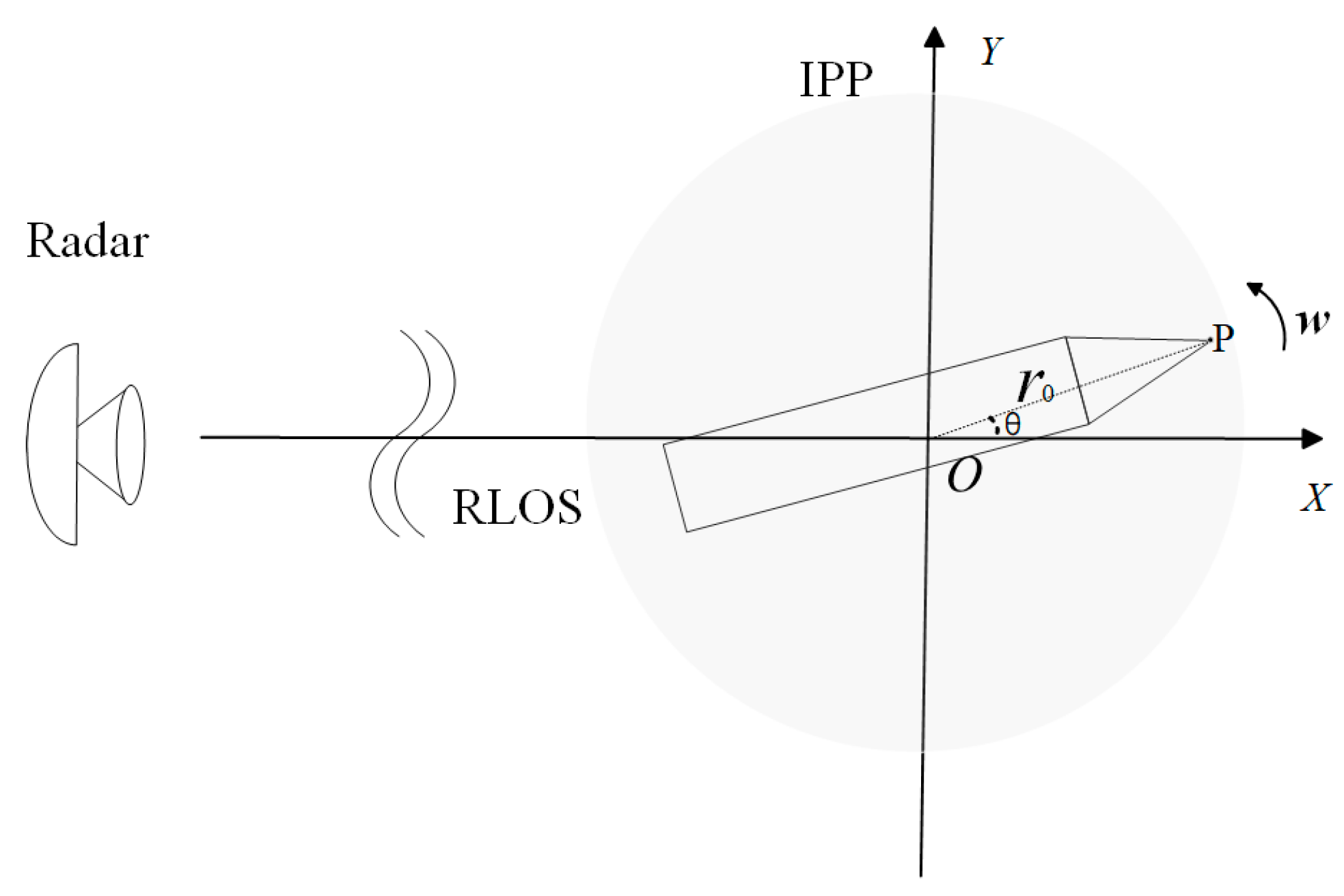

2. ISAR Imaging Mode and Signal Models

3. The IPGRA Algorithm and Its Limitation

3.1. Principle and Implementation of IPGRA

- 1.

- Phase Characteristics of Rotational Motion

- 2.

- Block-wise Estimation and Global Compensation

- 3.

- Resample for Phase Correction

- 4.

- Convergence Quantification

- 1.

- Preprocessing

- 2.

- Block-wise Phase Error Extraction

- 3.

- Resample

- 4.

- Iteration

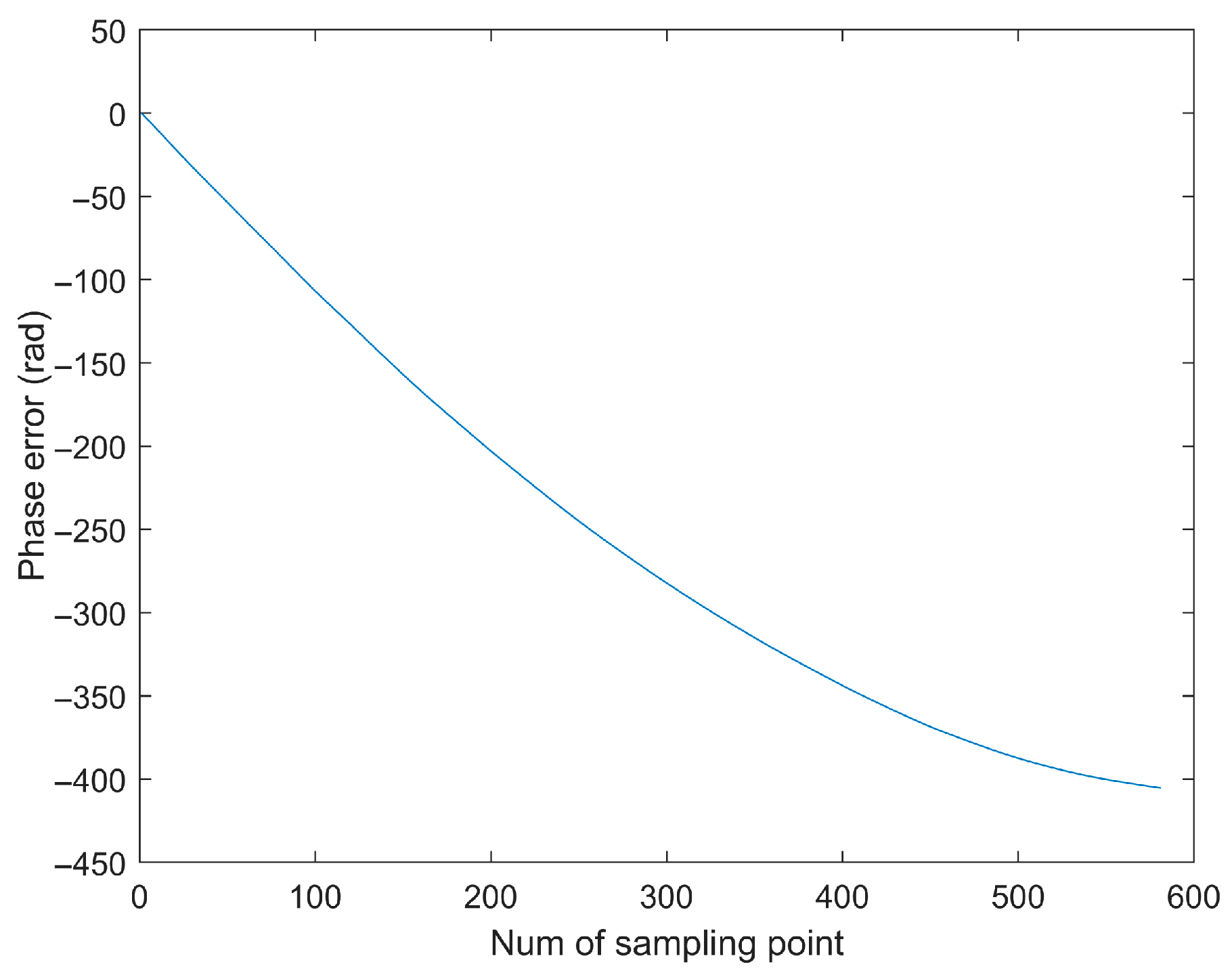

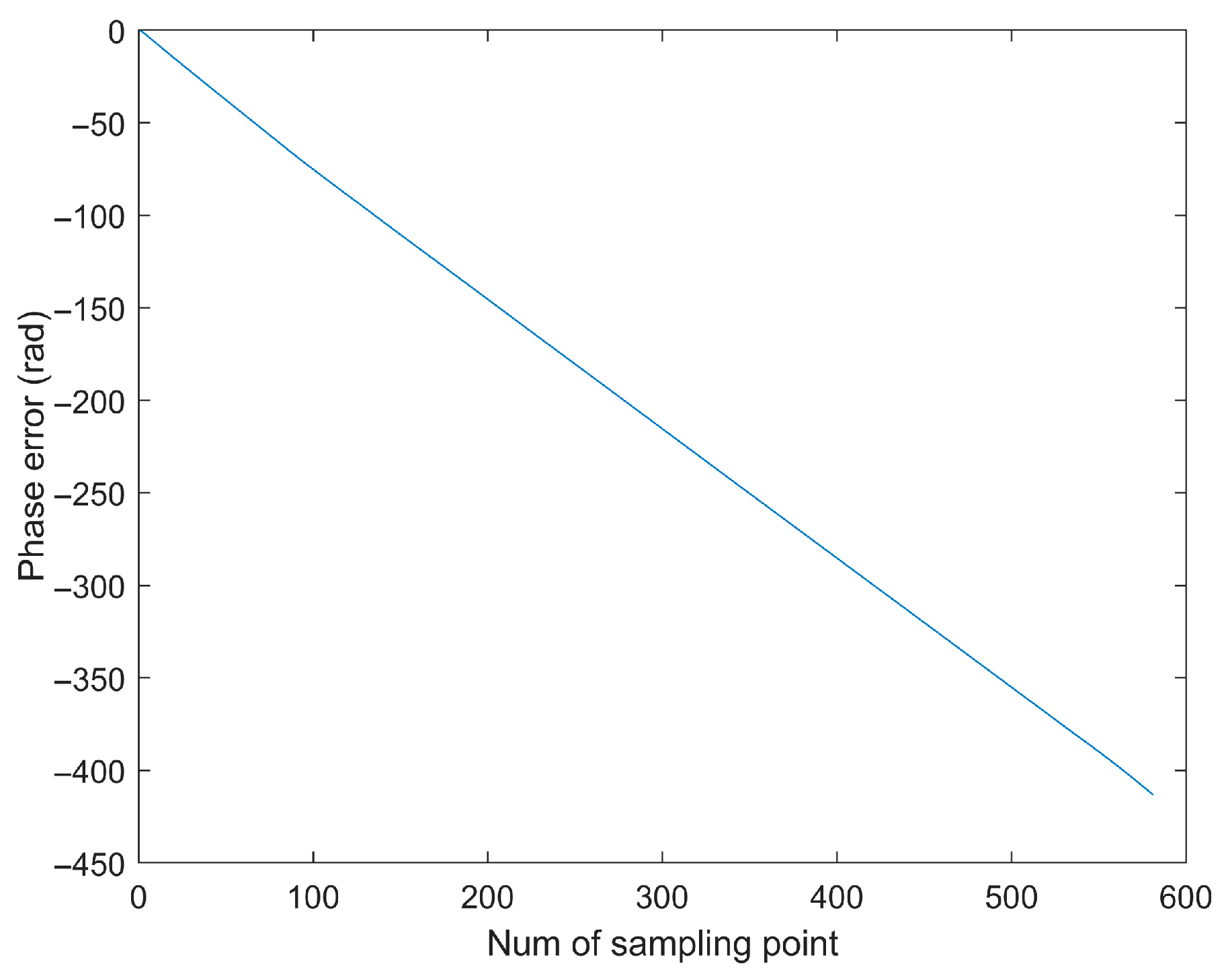

3.2. Limitations of IPGRA

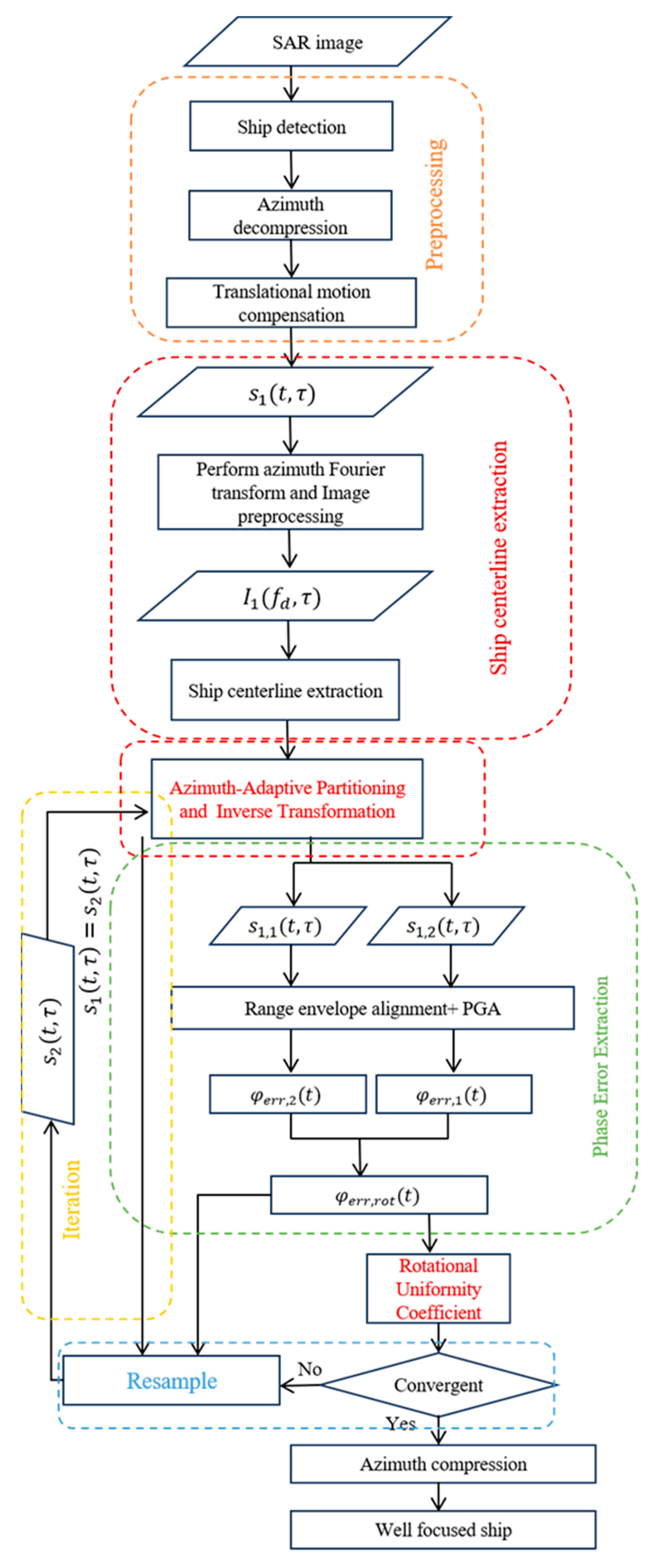

4. Proposed Improved IPGRA

4.1. Centerline-Driven Azimuth Adaptive Partitioning

- 1.

- Coarse Image Formation

- 2.

- Centerline Extraction

- 3.

- Adaptive Partitioning

- 4.

- Signal Reconstruction

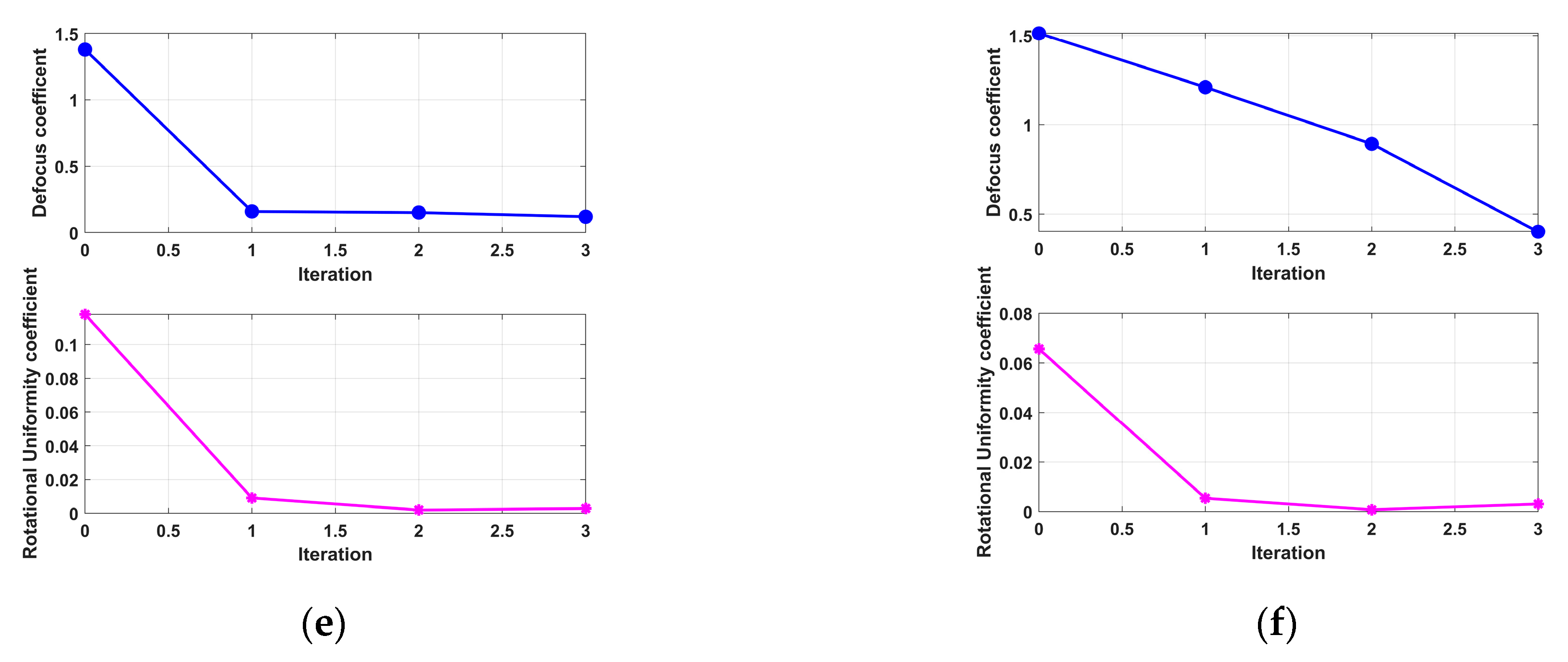

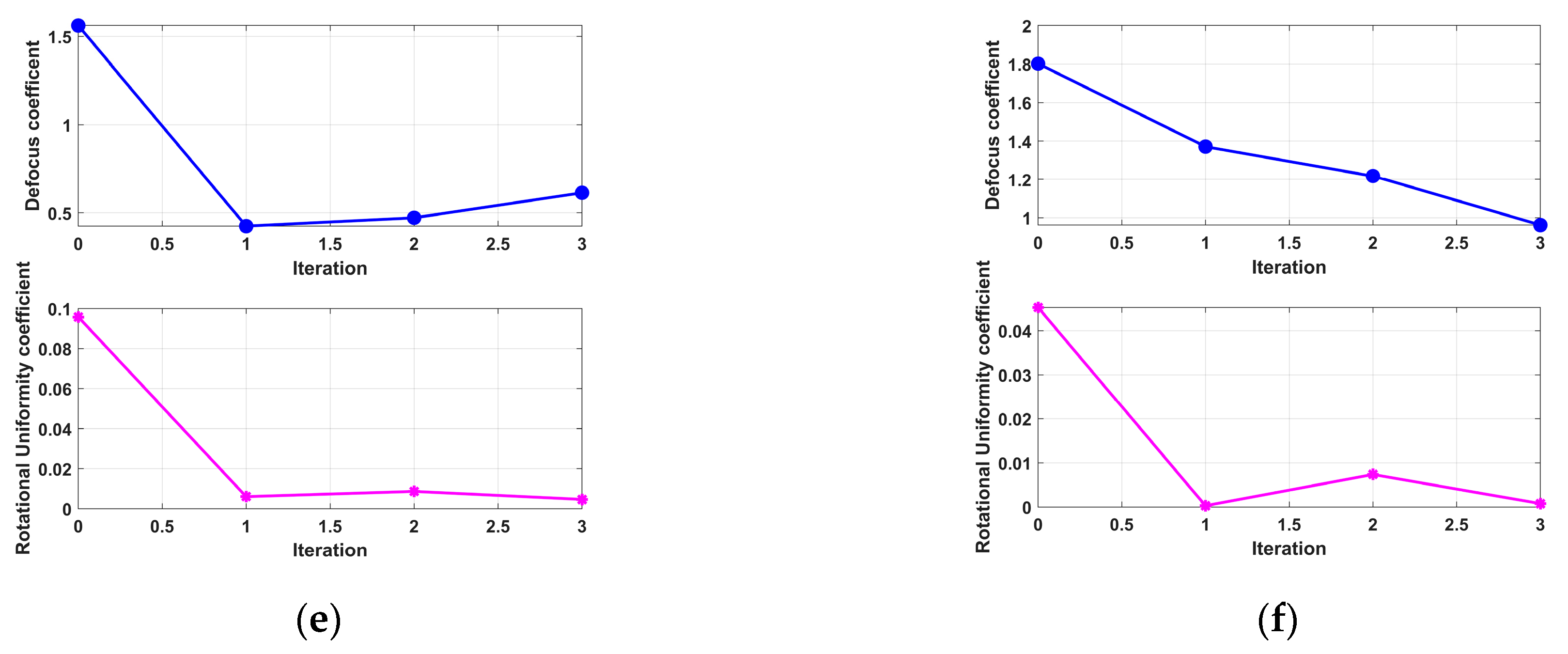

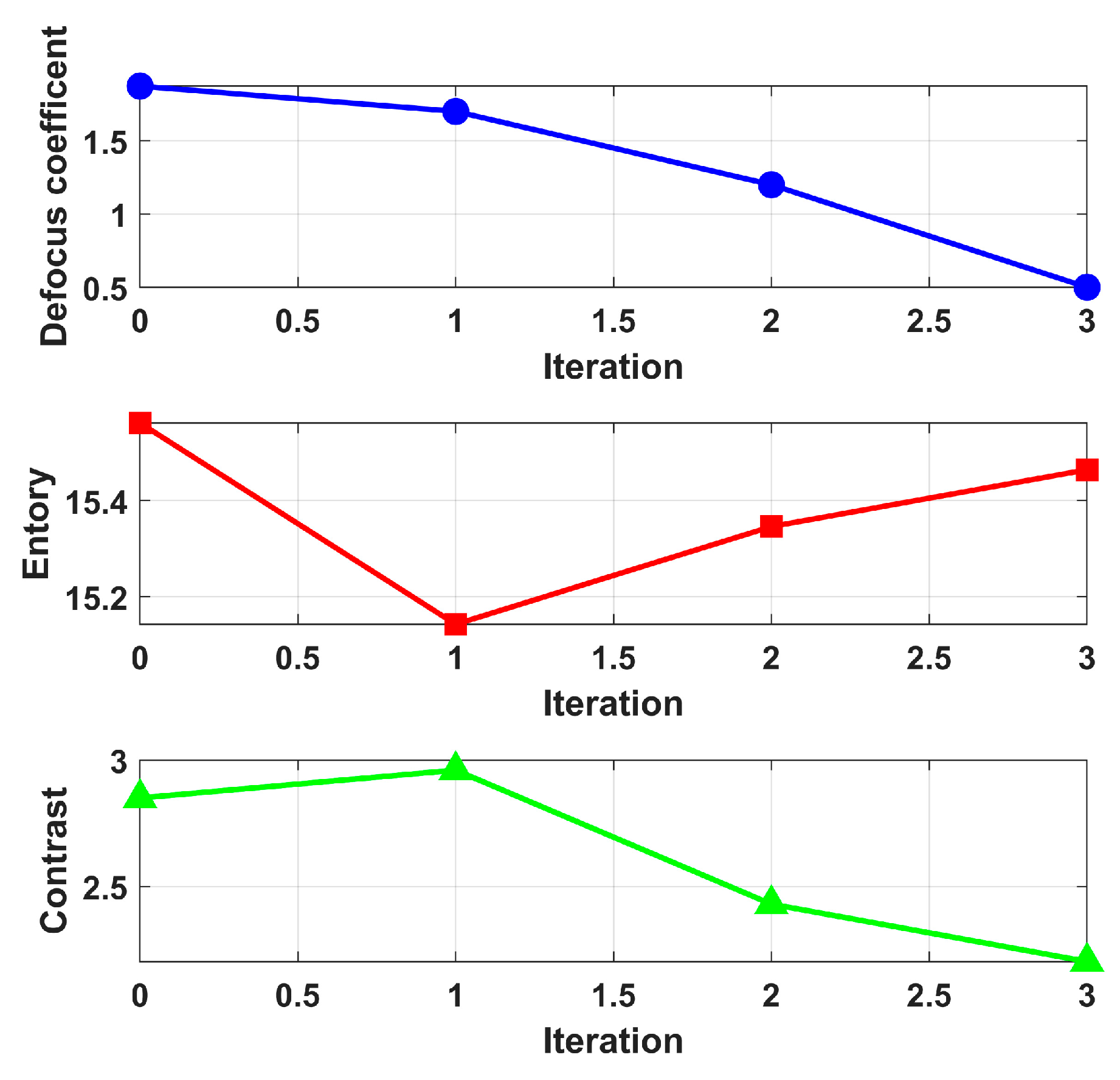

4.2. Rotational Uniformity Coefficient β for Stable Convergence

4.3. IIPGRA Processing Flow

- 1.

- Translational Motion Compensation

- 2.

- Ship Centerline Extraction via enhanced RANSAC

- 3.

- Azimuth-Adaptive Partitioning

- 4.

- Phase Error Extraction

- 5.

- Resample

- 6.

- Iteration

4.4. Sensitivity and Robustness Analysis of Centerline Deviation

4.5. Computational Complexity Analysis

- Coarse image formation:

- Centerline extraction:

- Adaptive partitioning and signal reconstruction:

- PGA-based phase error estimation:

- Resampling:

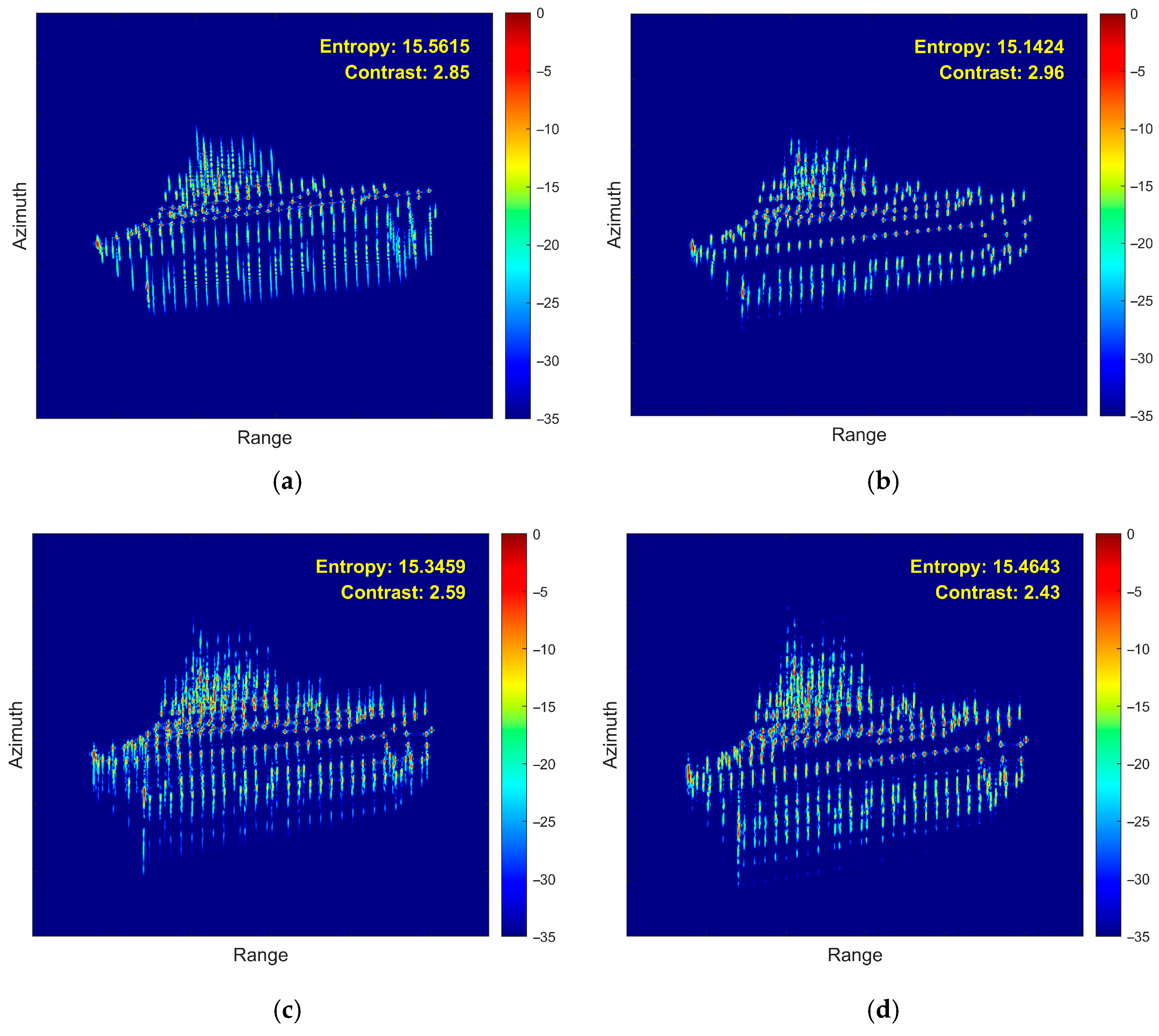

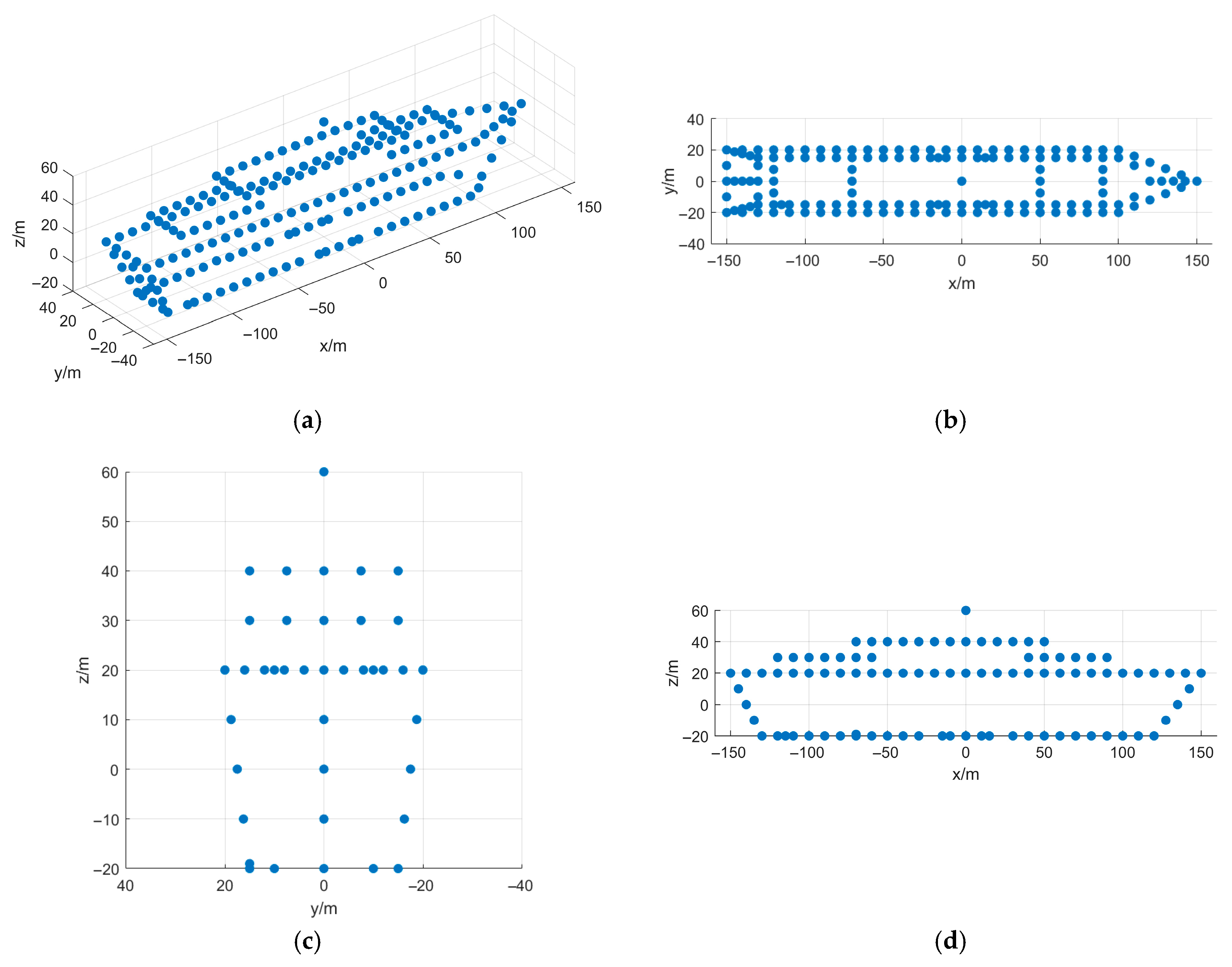

5. Simulation and Real-Measured ISAR Data Processing Results

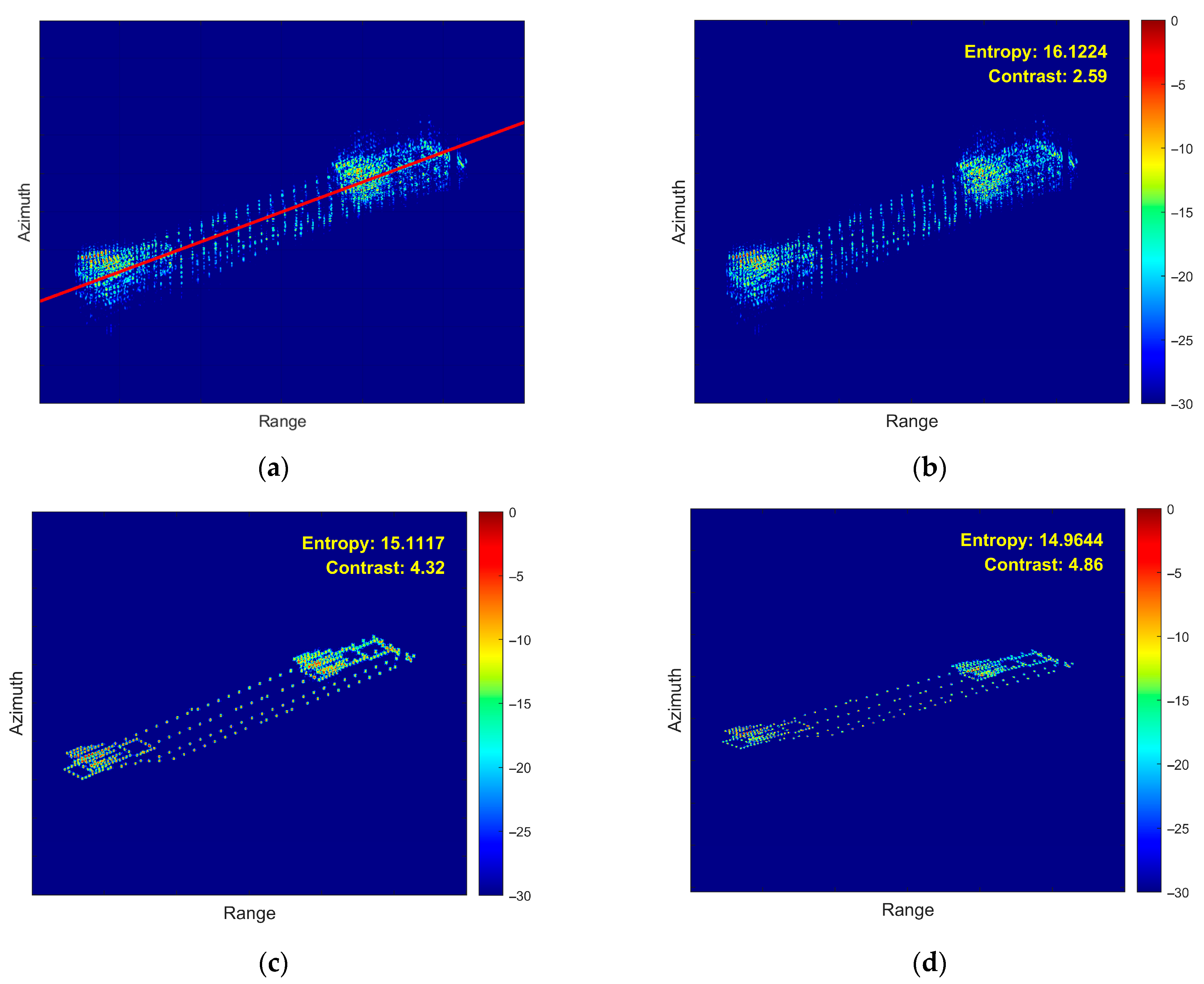

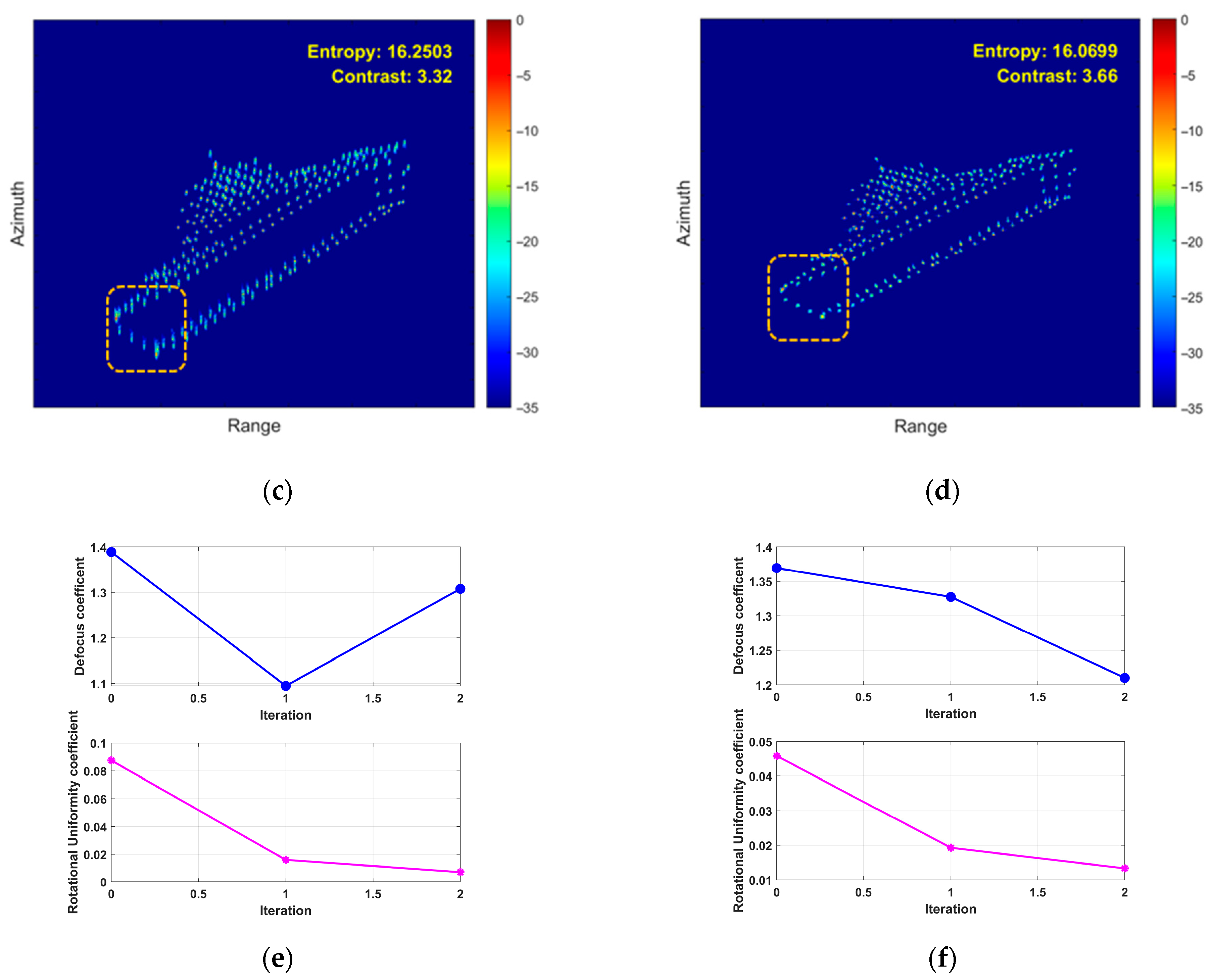

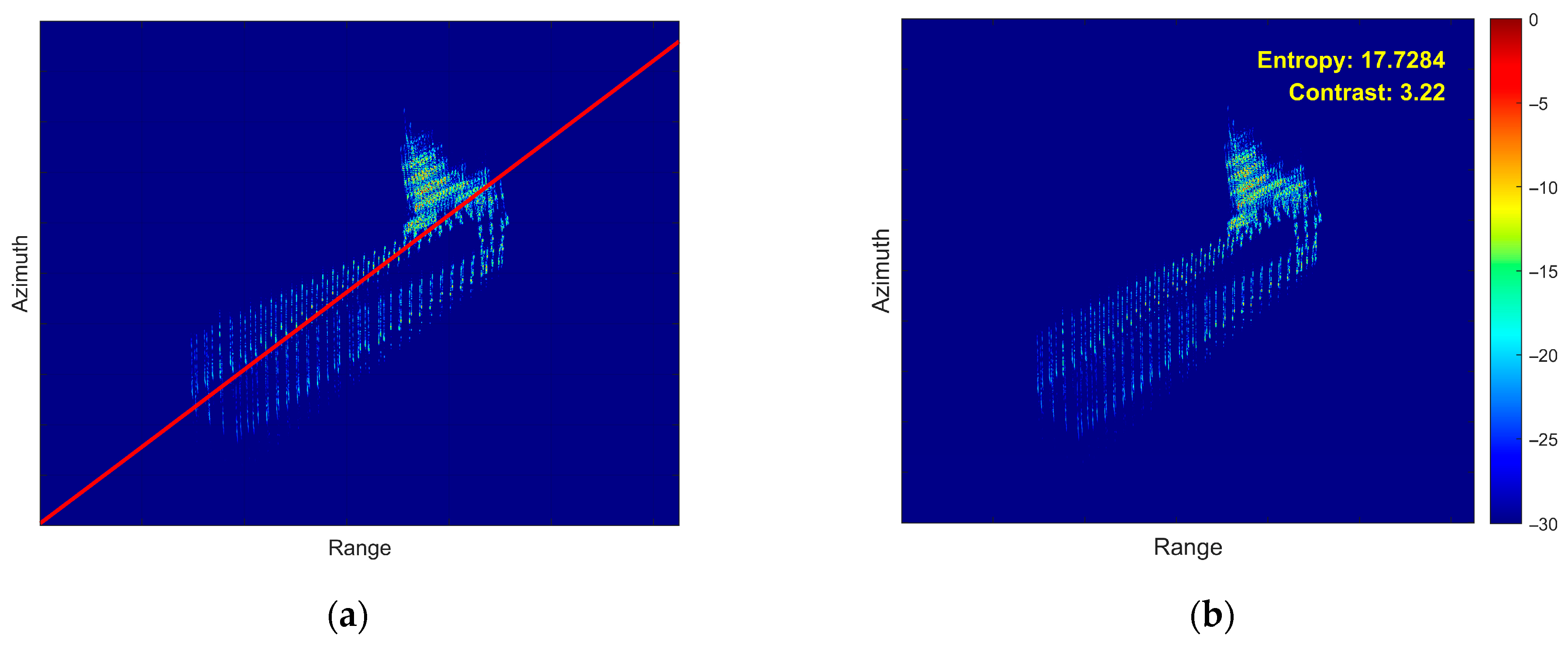

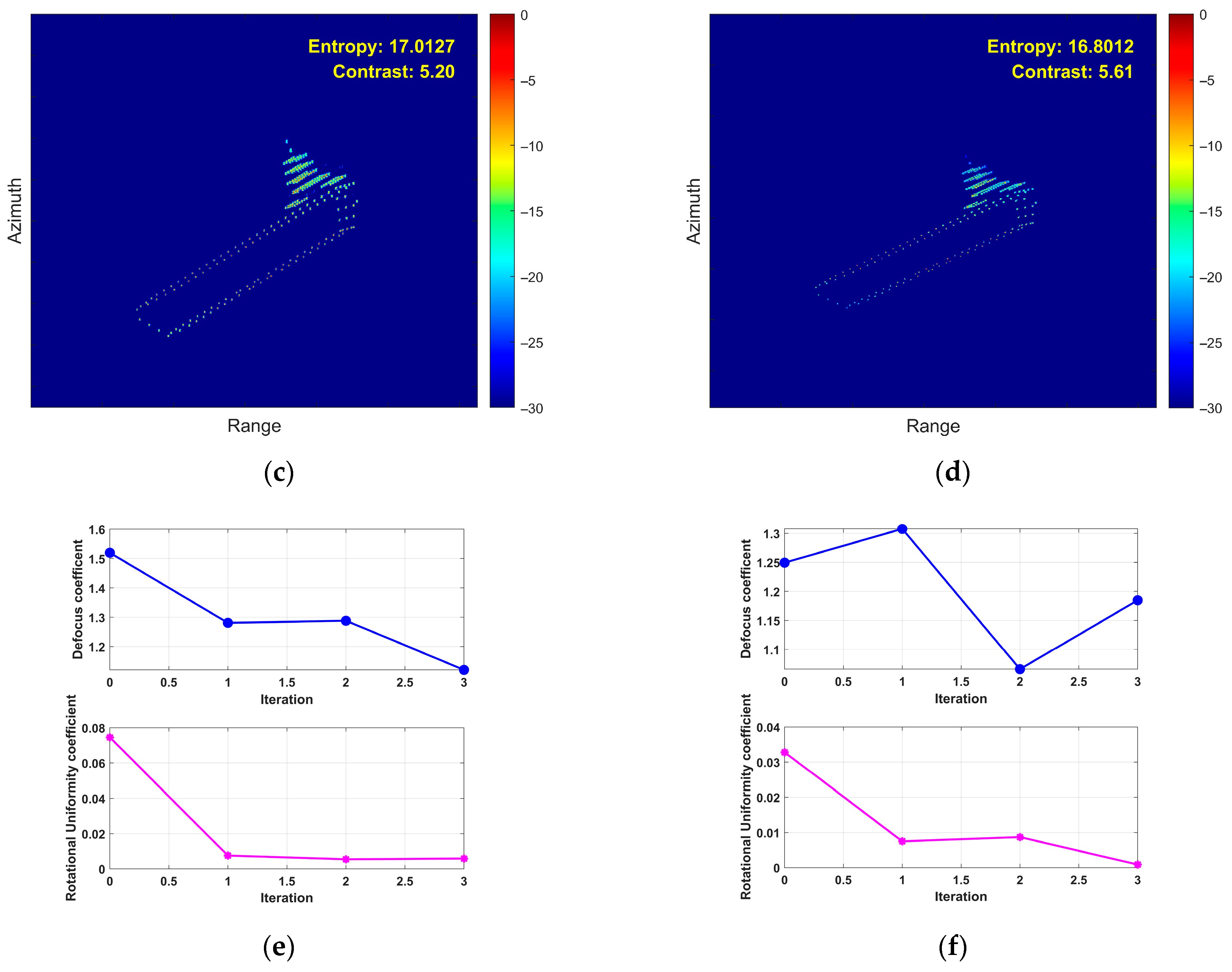

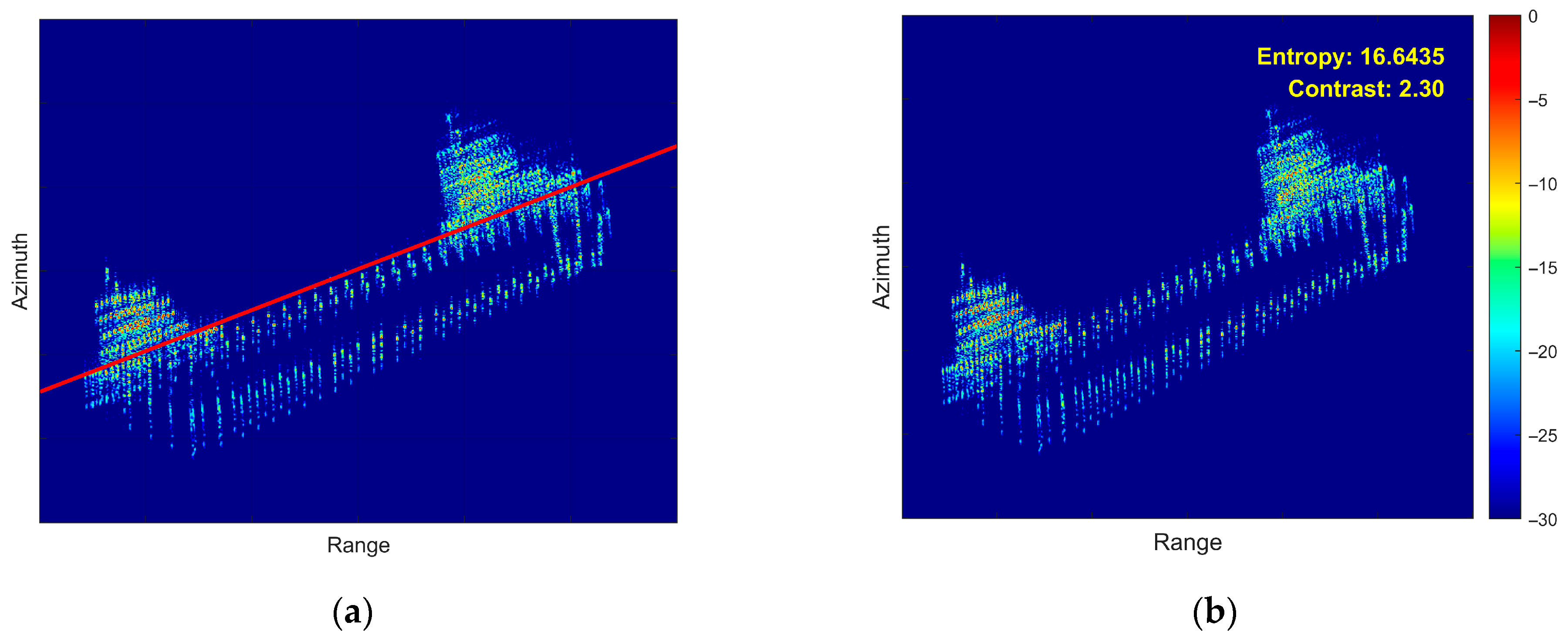

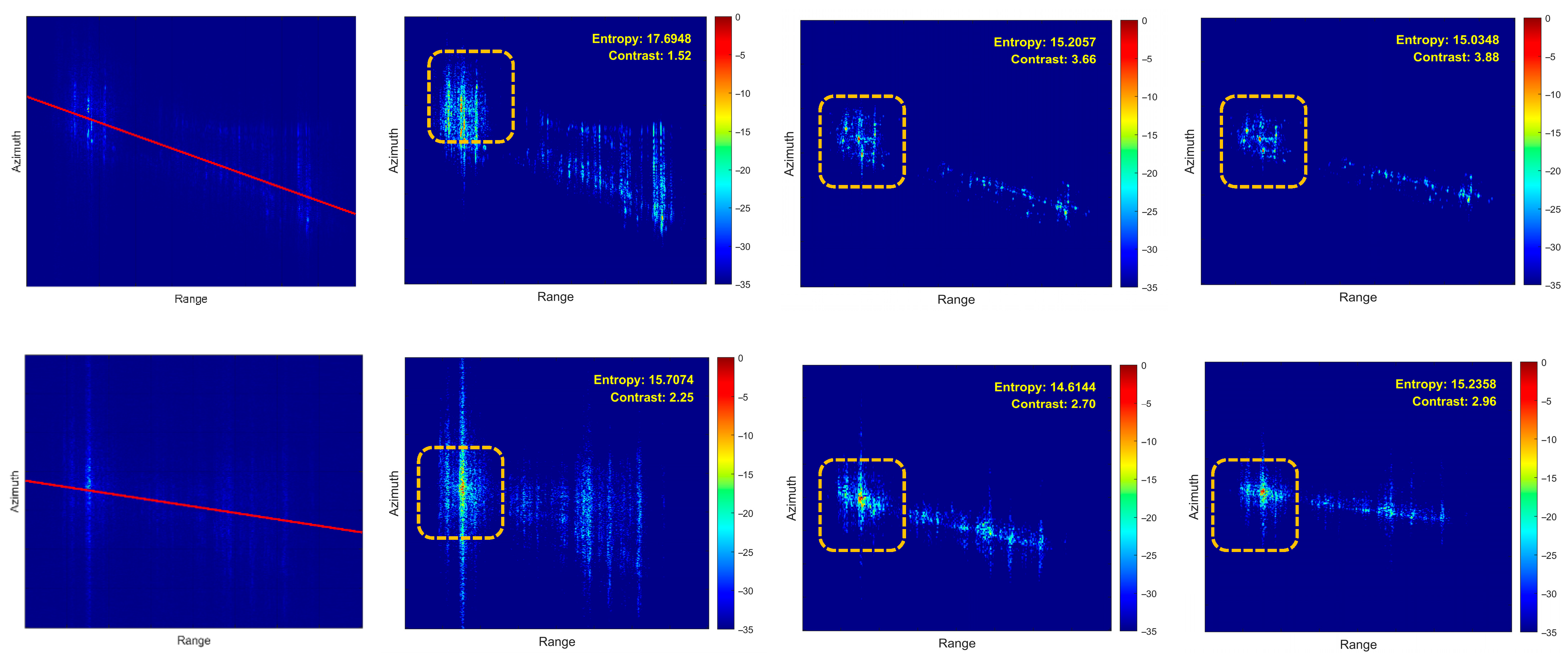

5.1. Simulated Data Verification

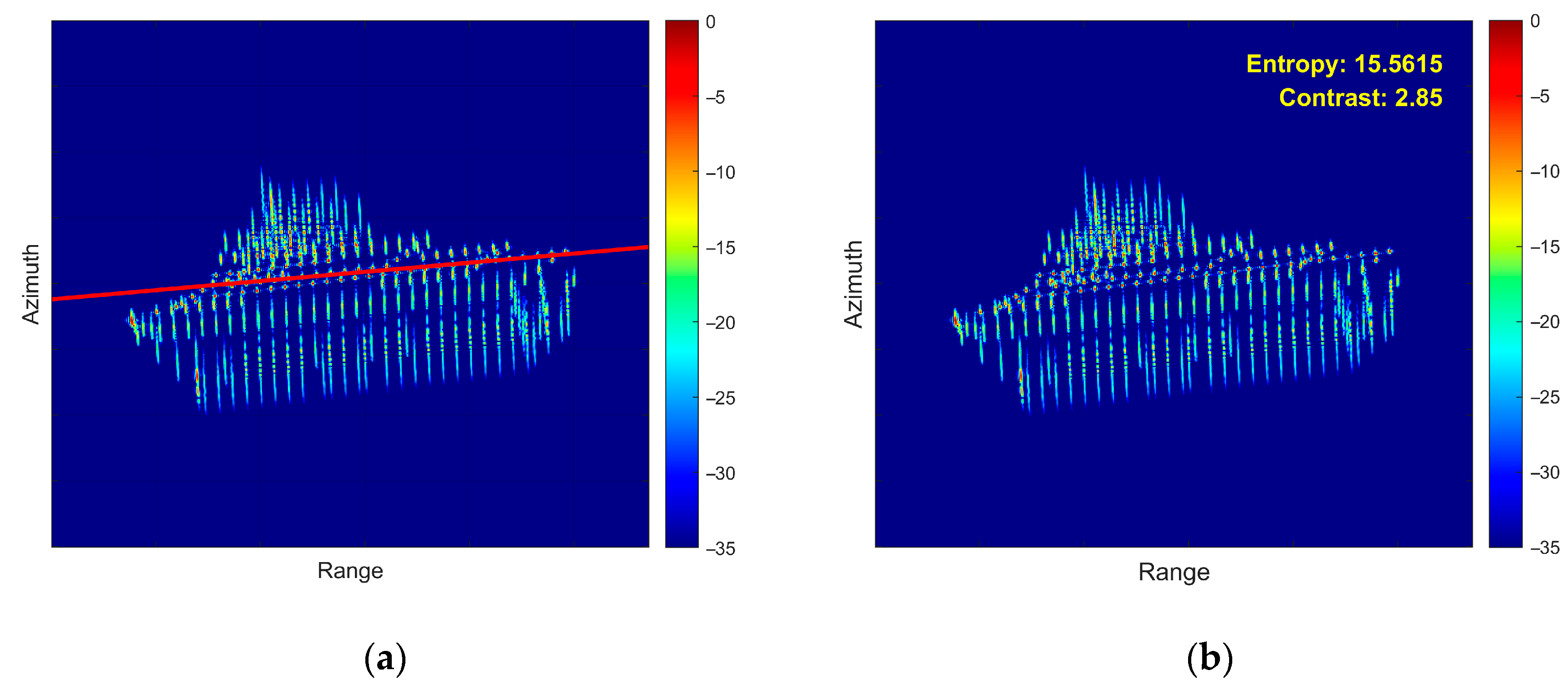

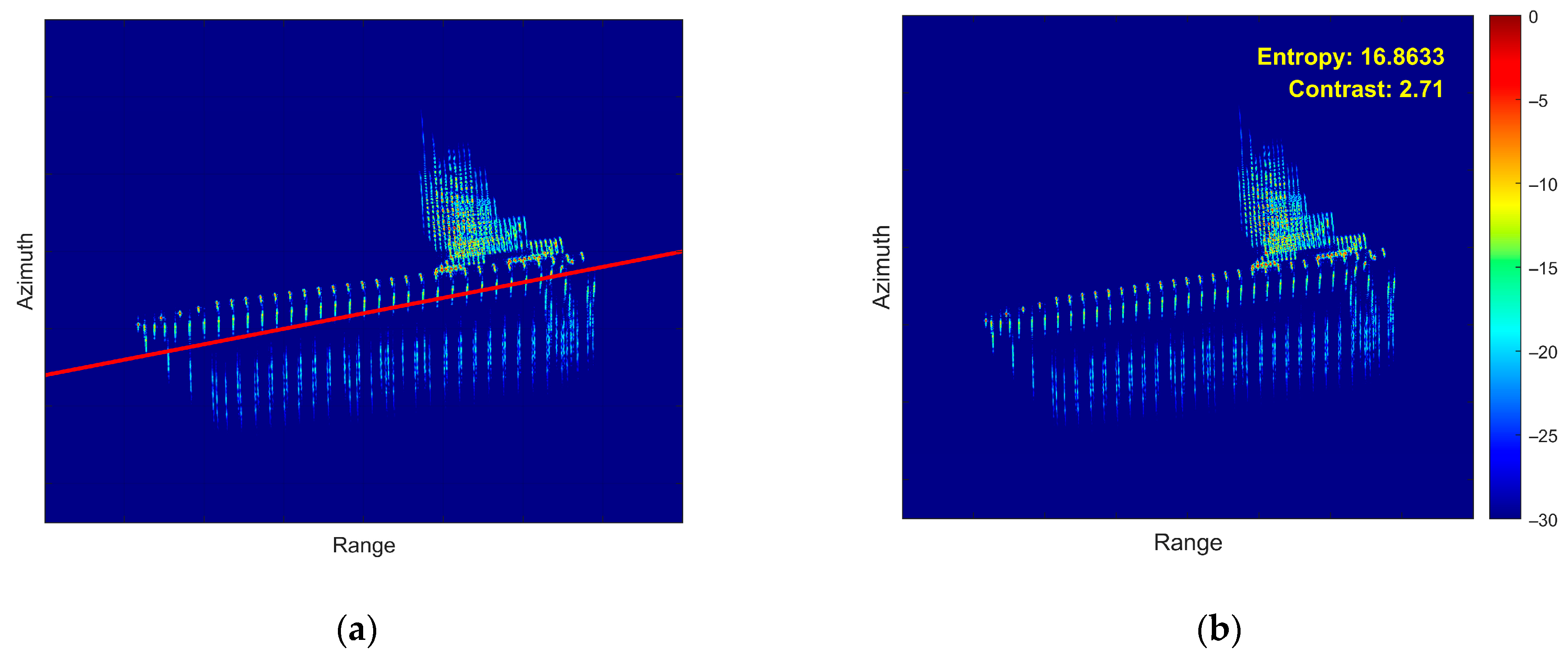

- (1)

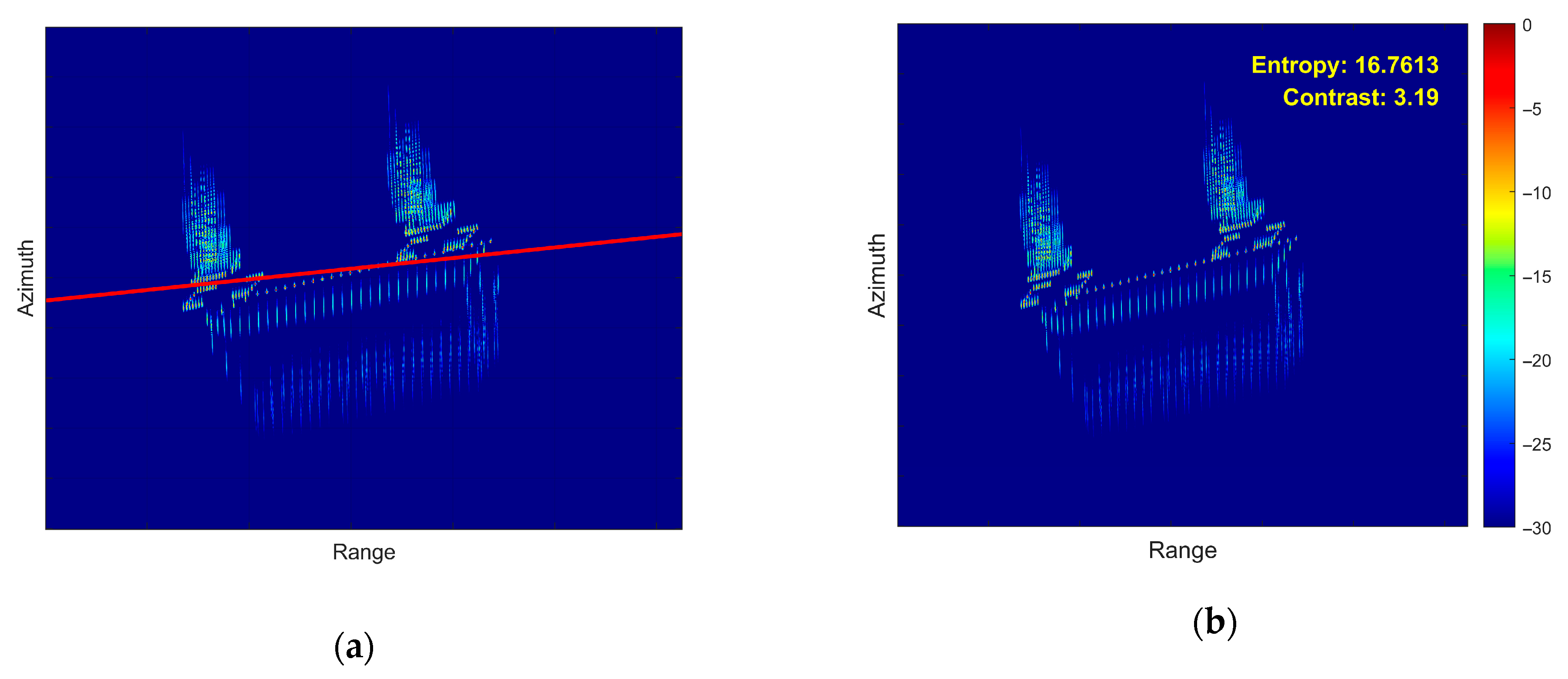

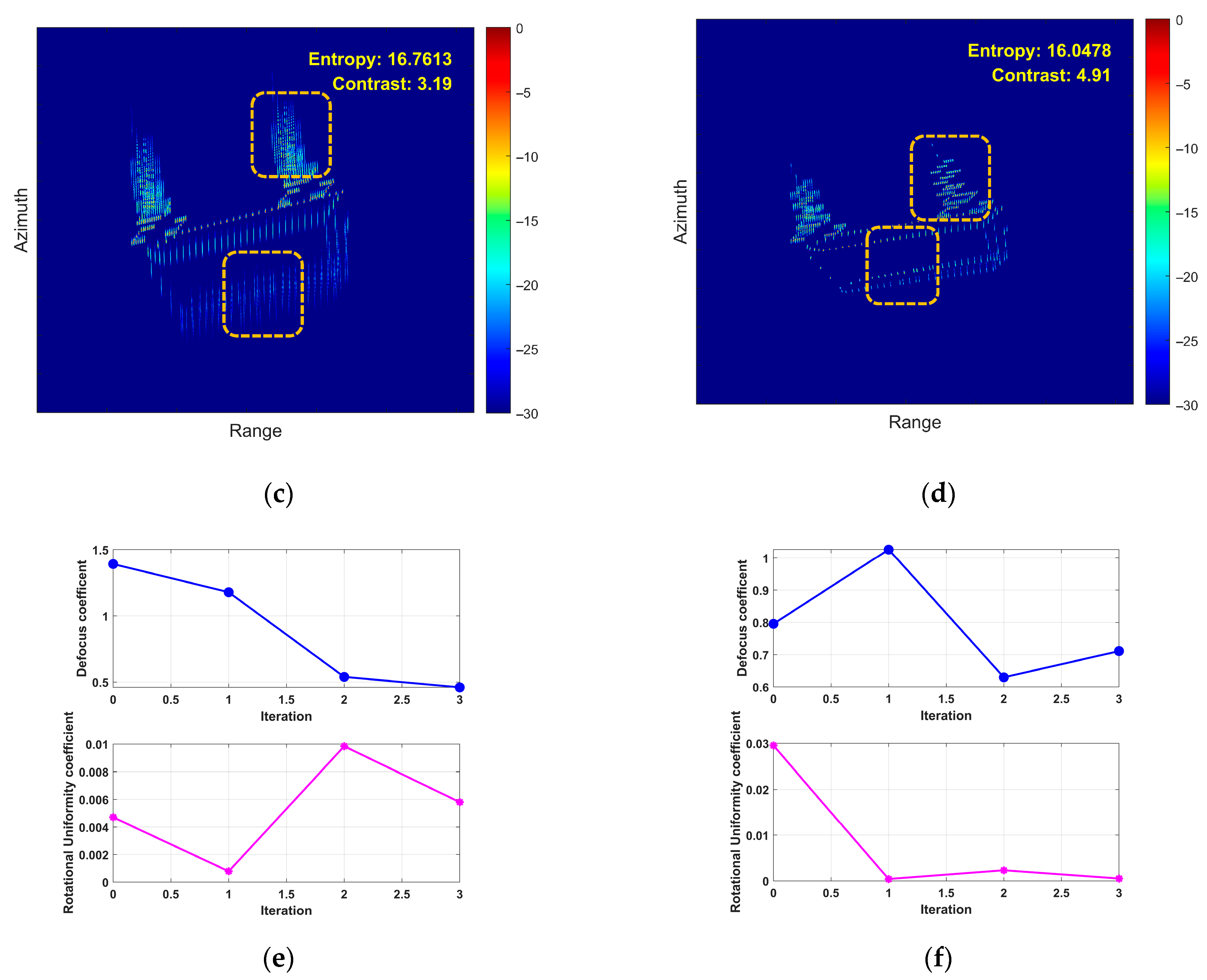

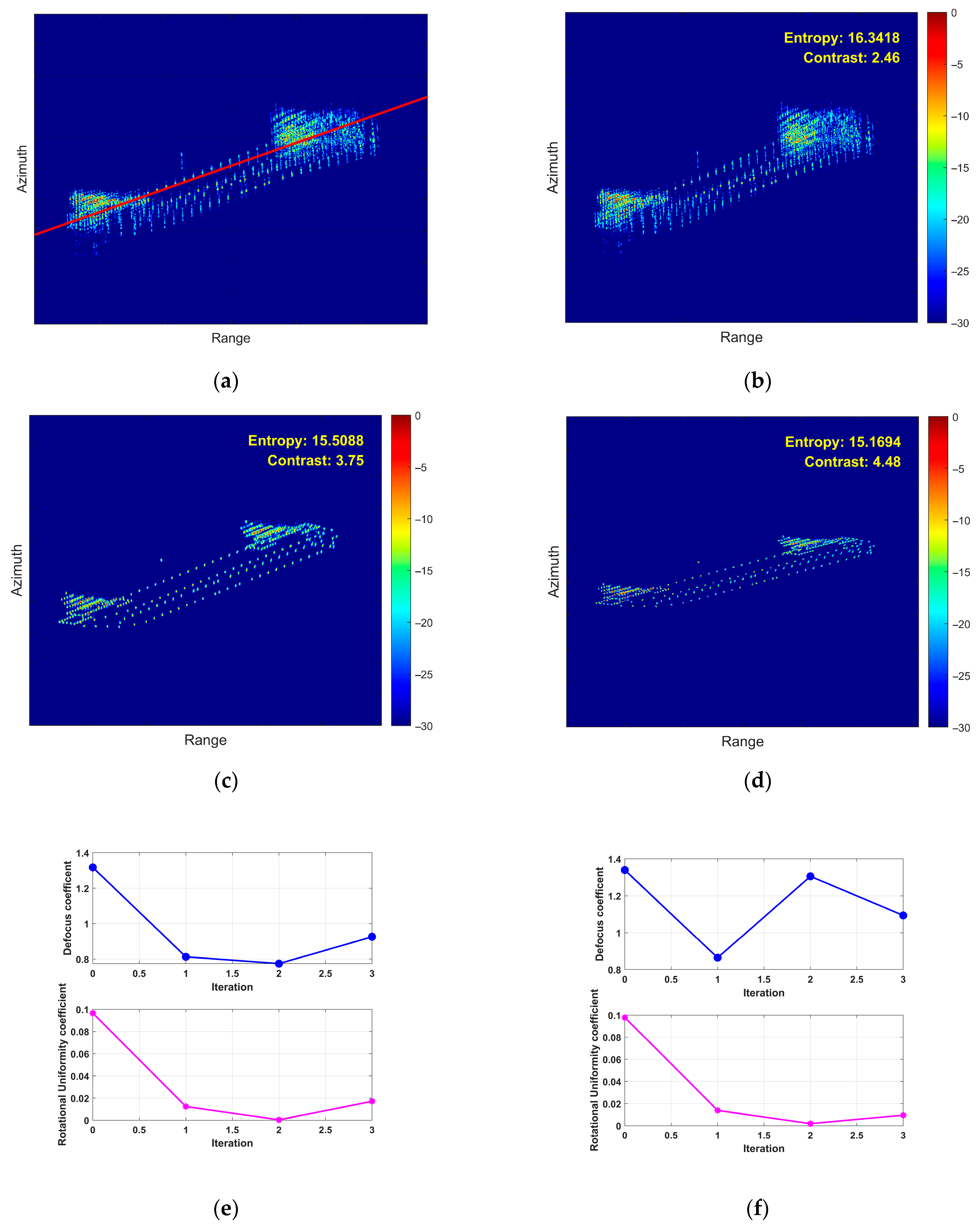

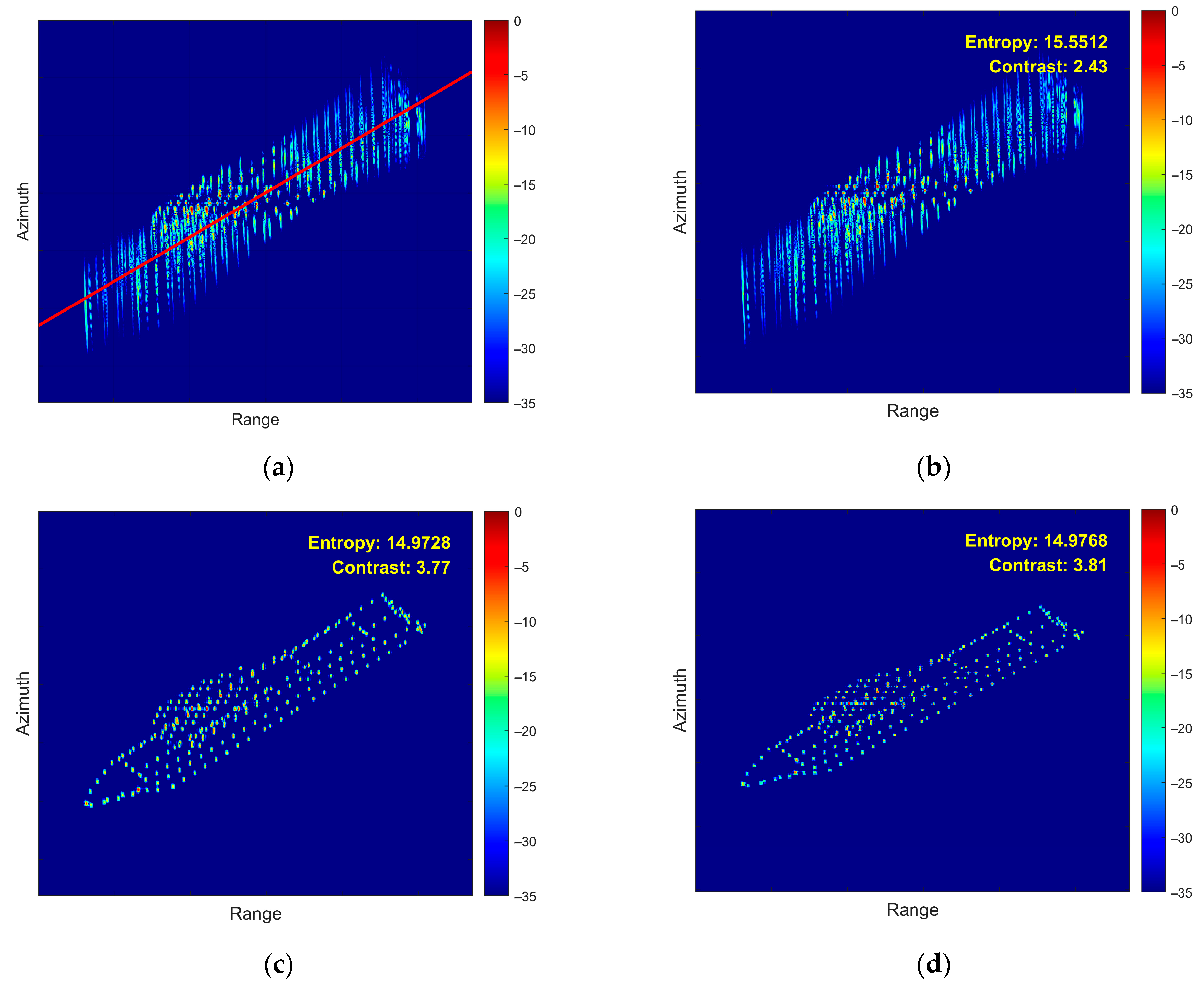

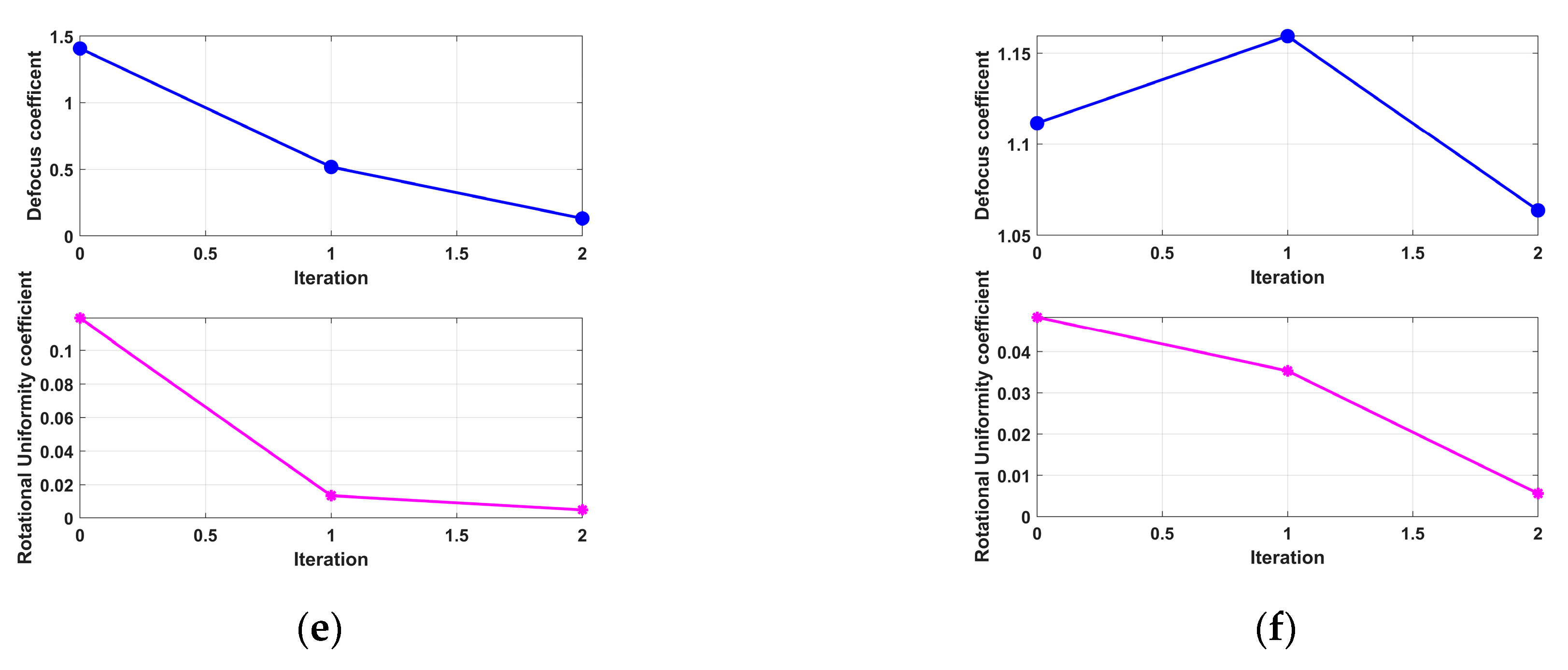

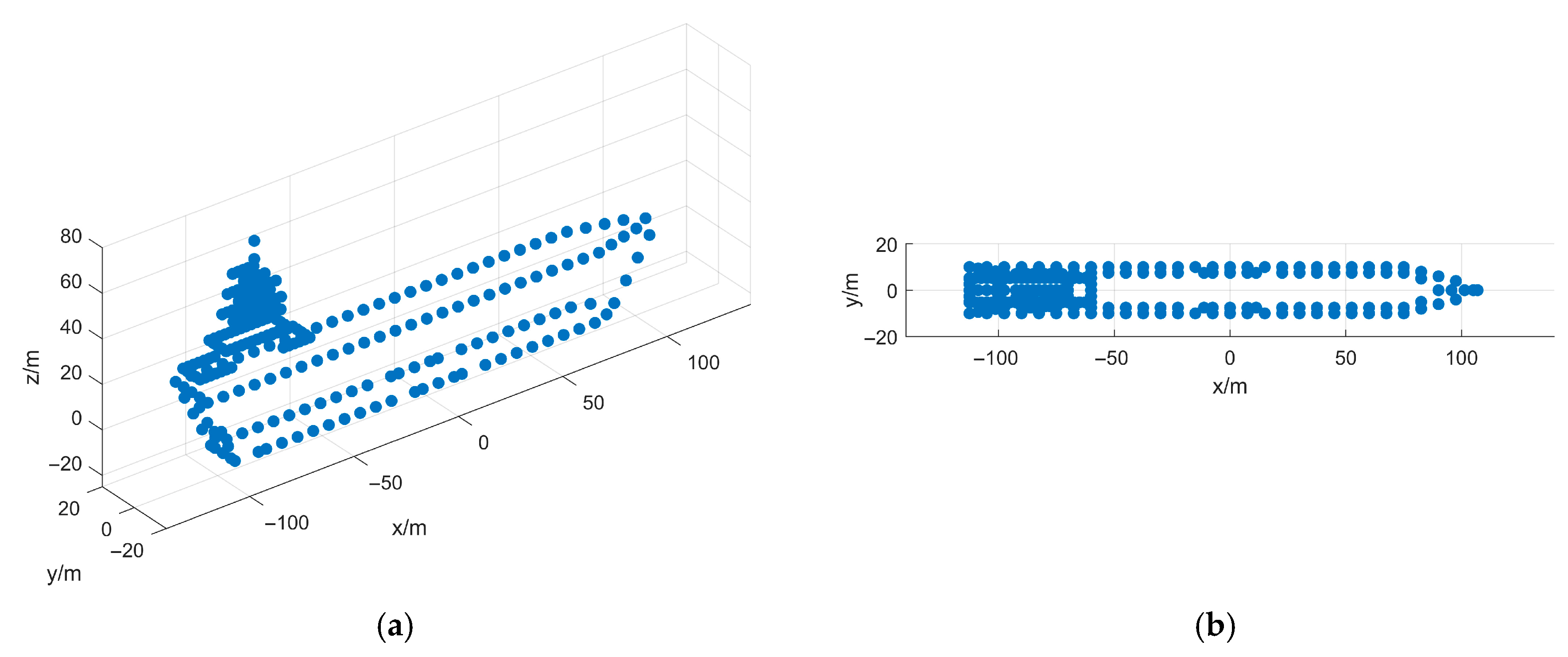

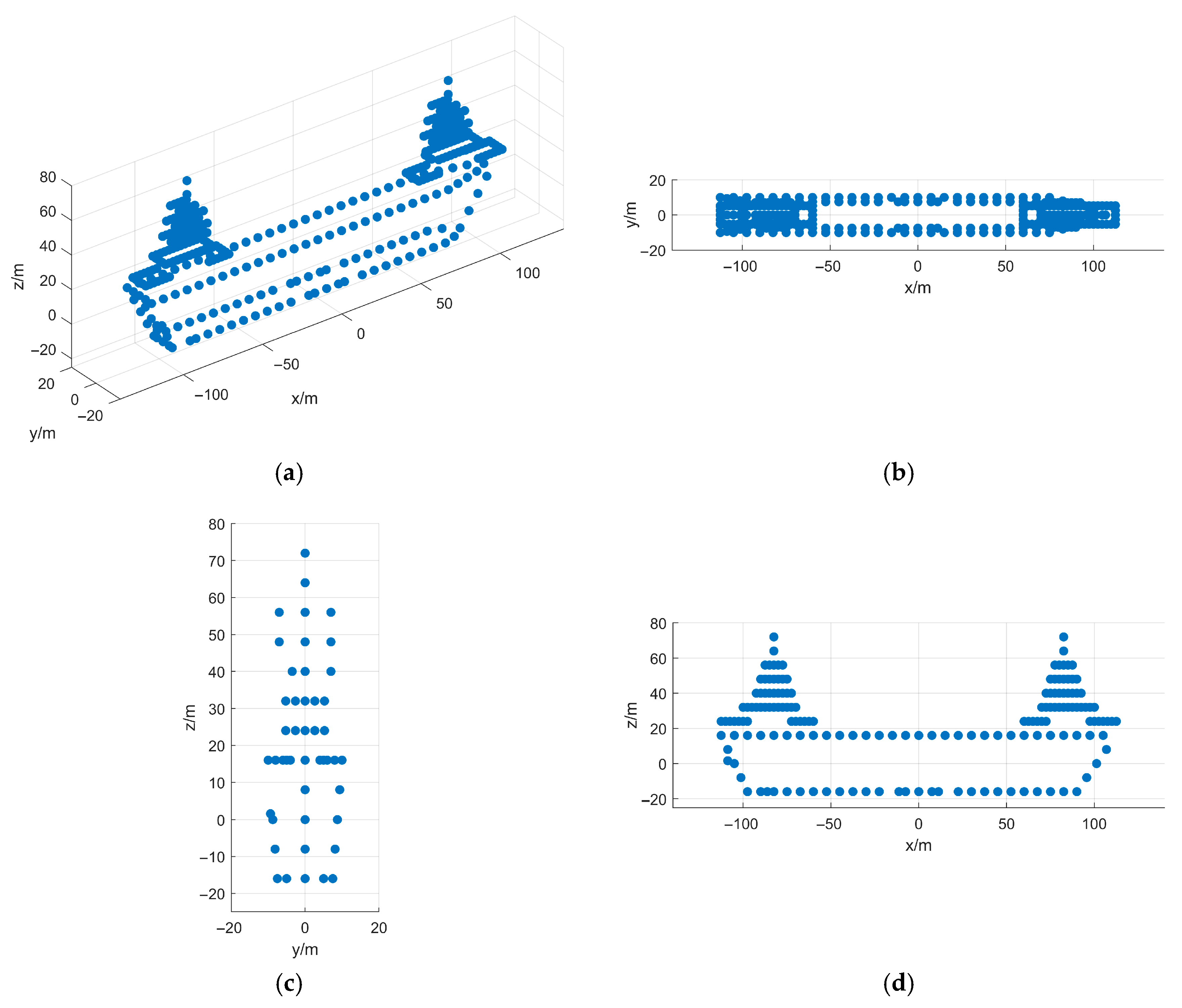

- First Experiment: Roll Motion Scenario

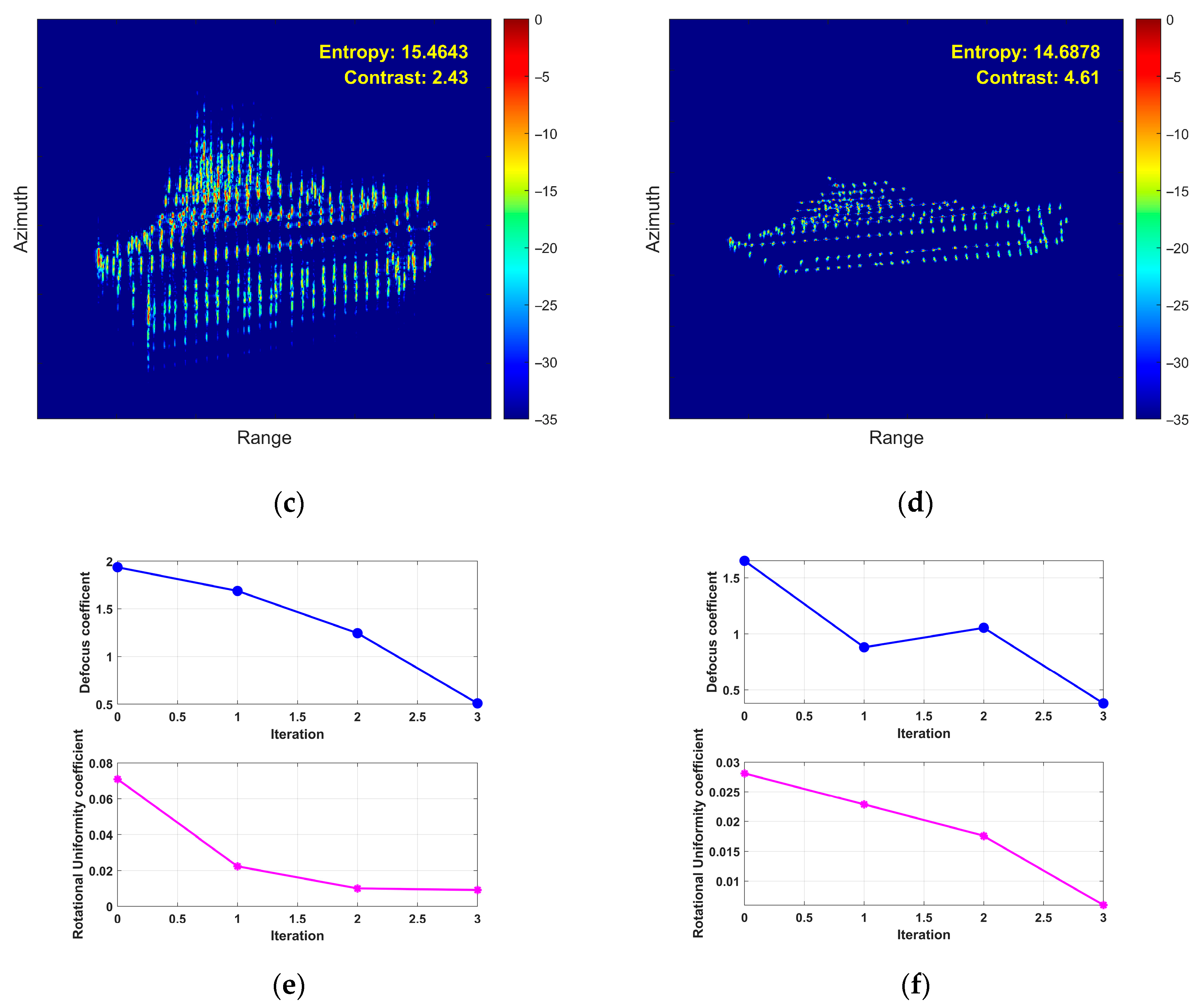

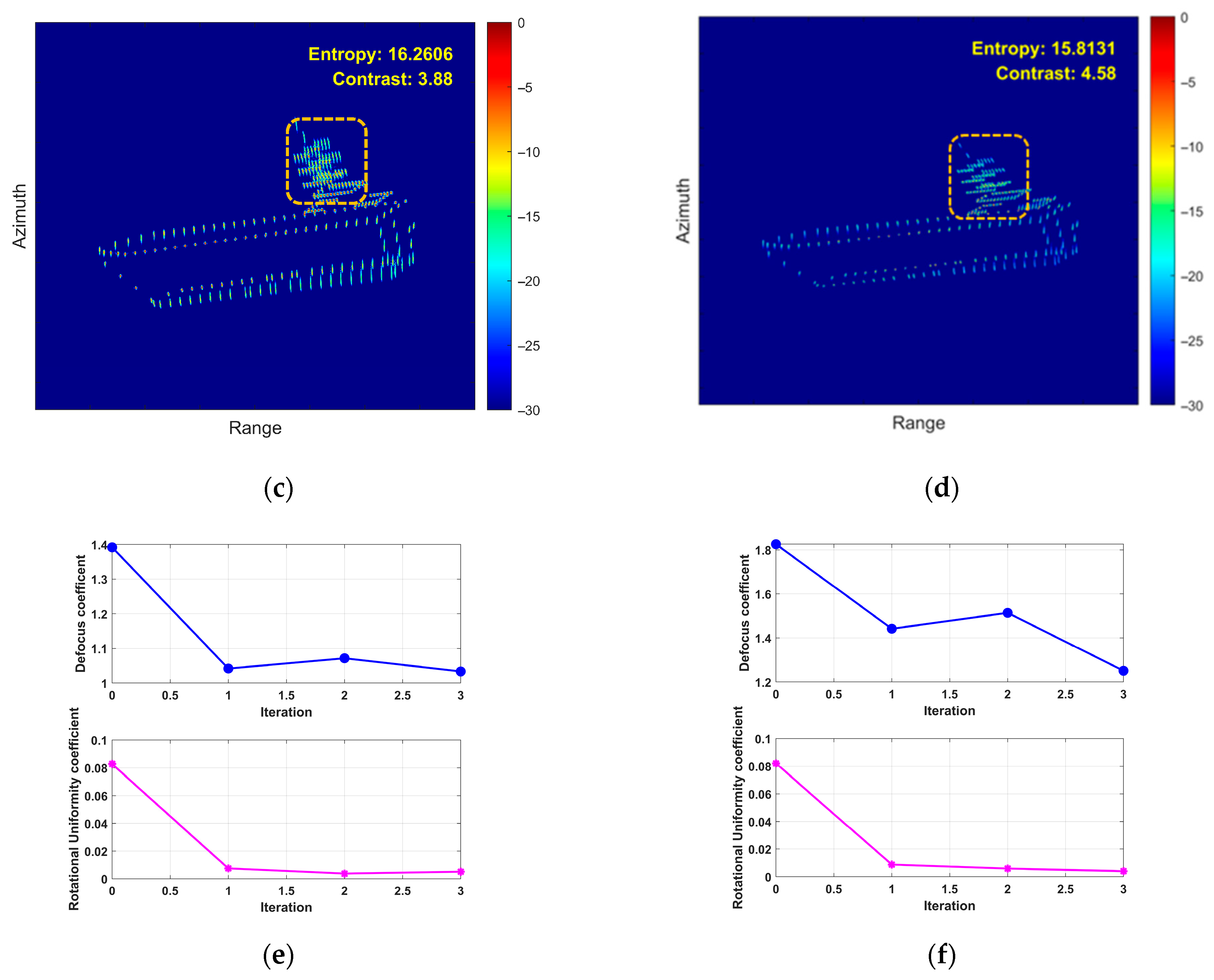

- (2)

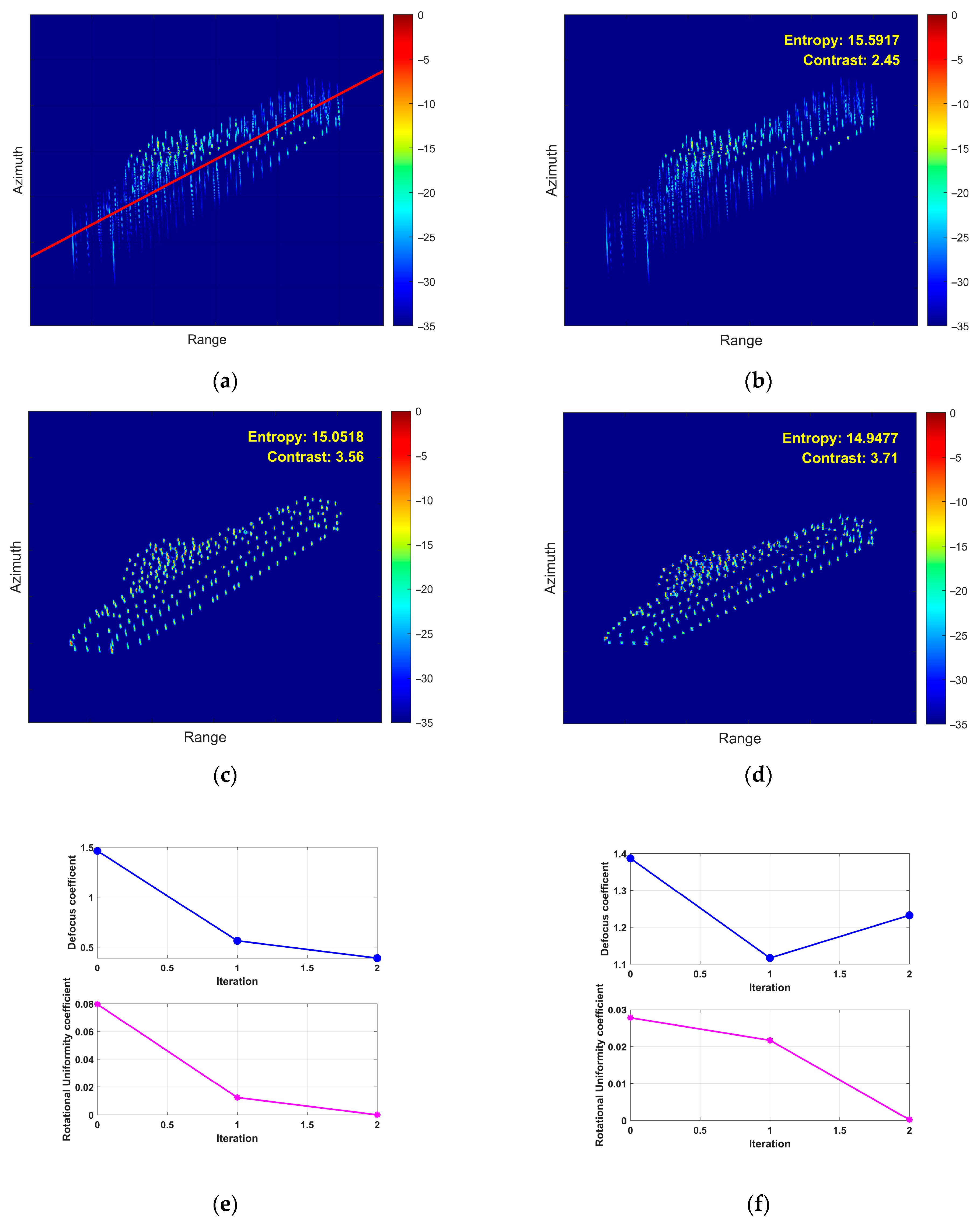

- Second Experiment: Pitch Motion Scenario

- (3)

- Third Experiment: Yaw Motion Scenario

- (4)

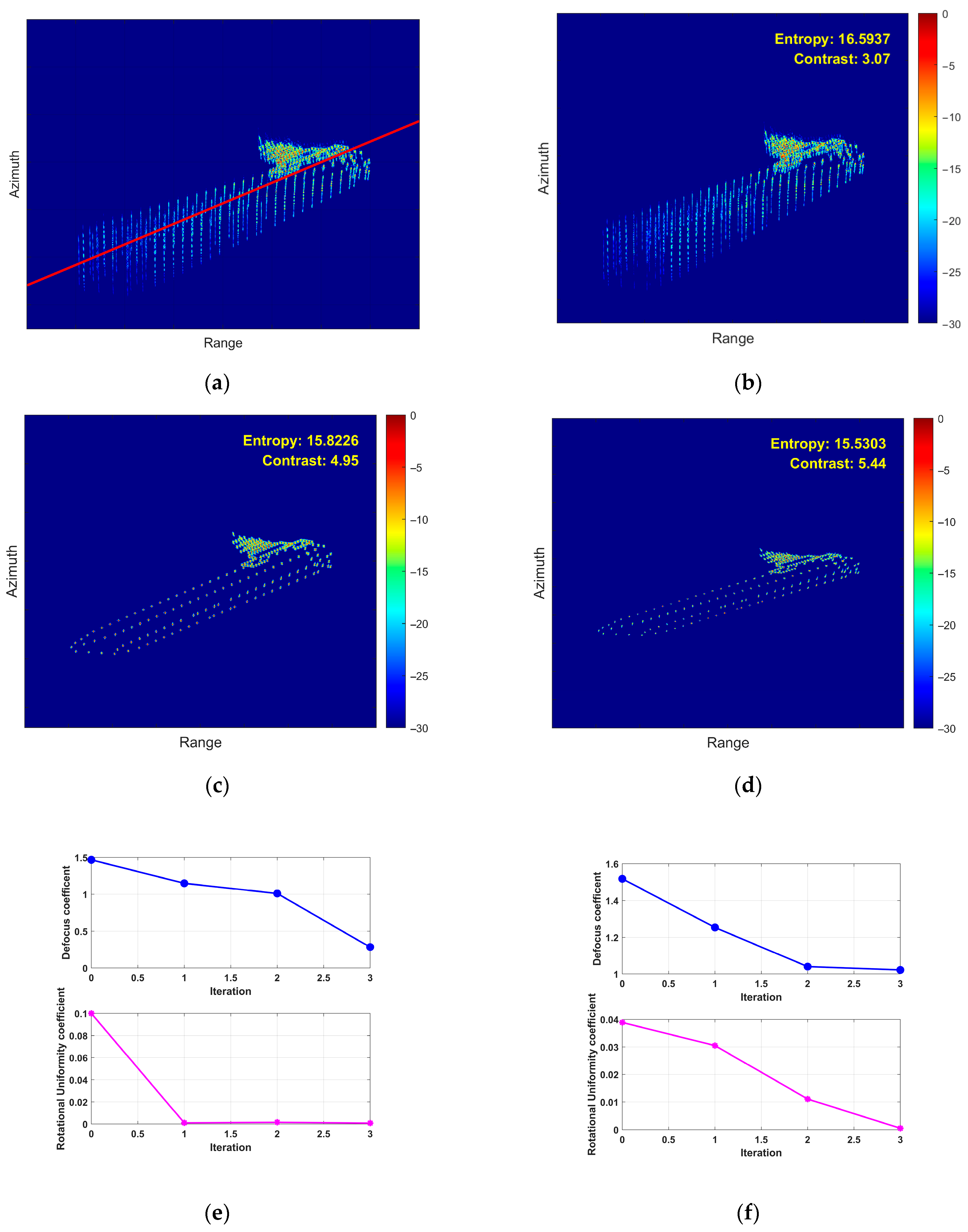

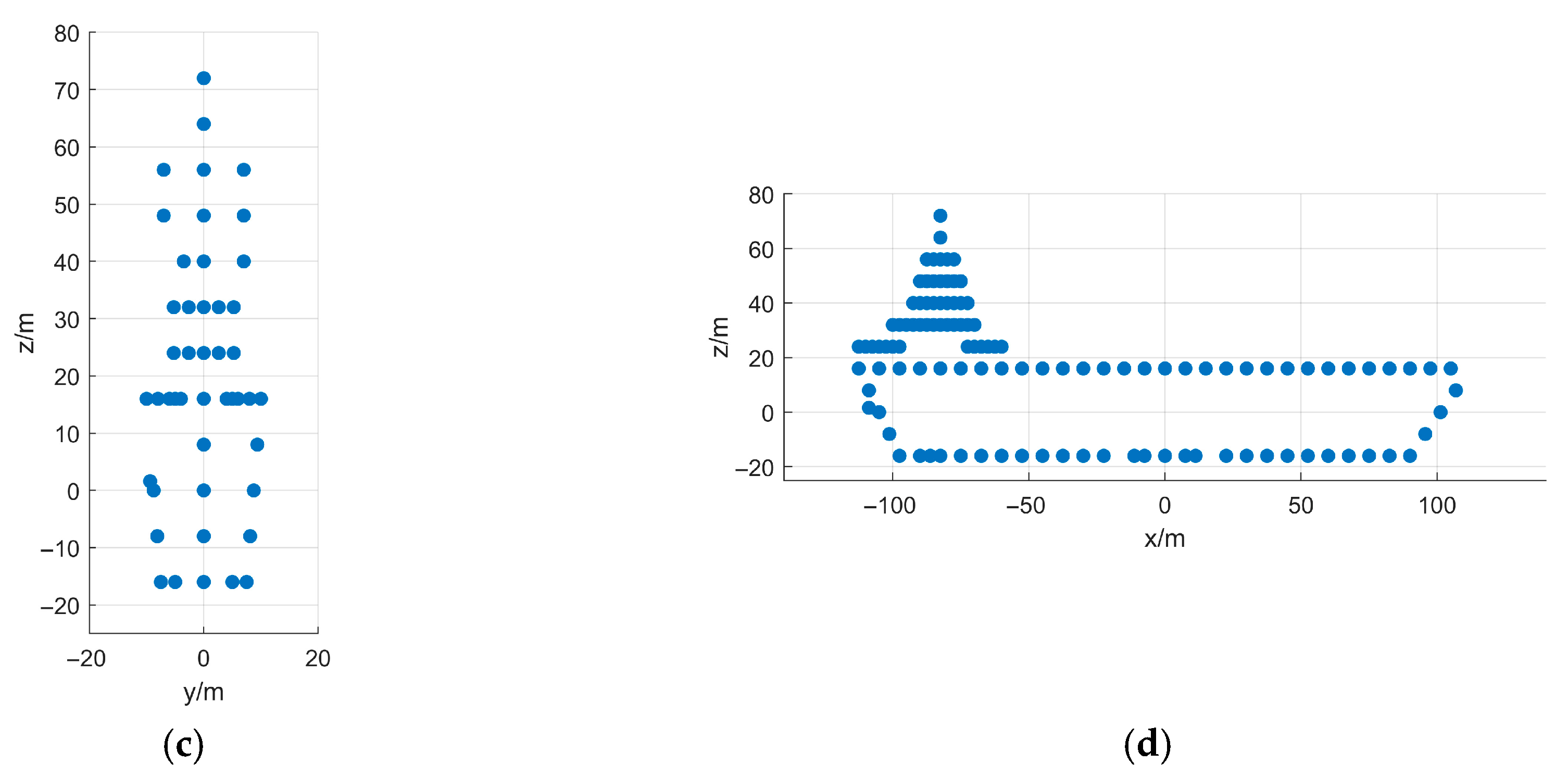

- Fourth Experiment: Coupled 3D Rotation

- (5)

- Fifth Experiment: Roll Motion Scenario in 0 dB SCR Environment

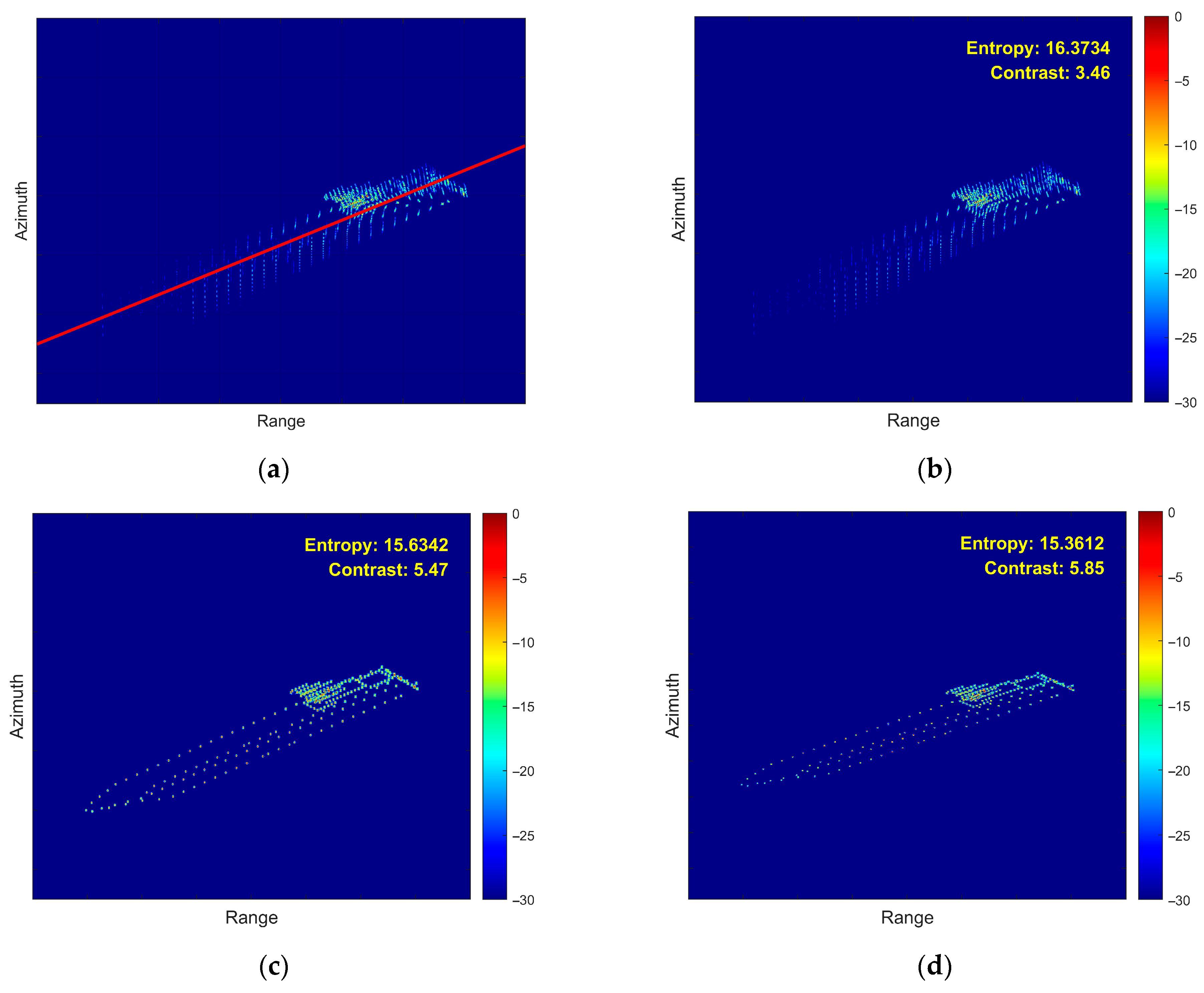

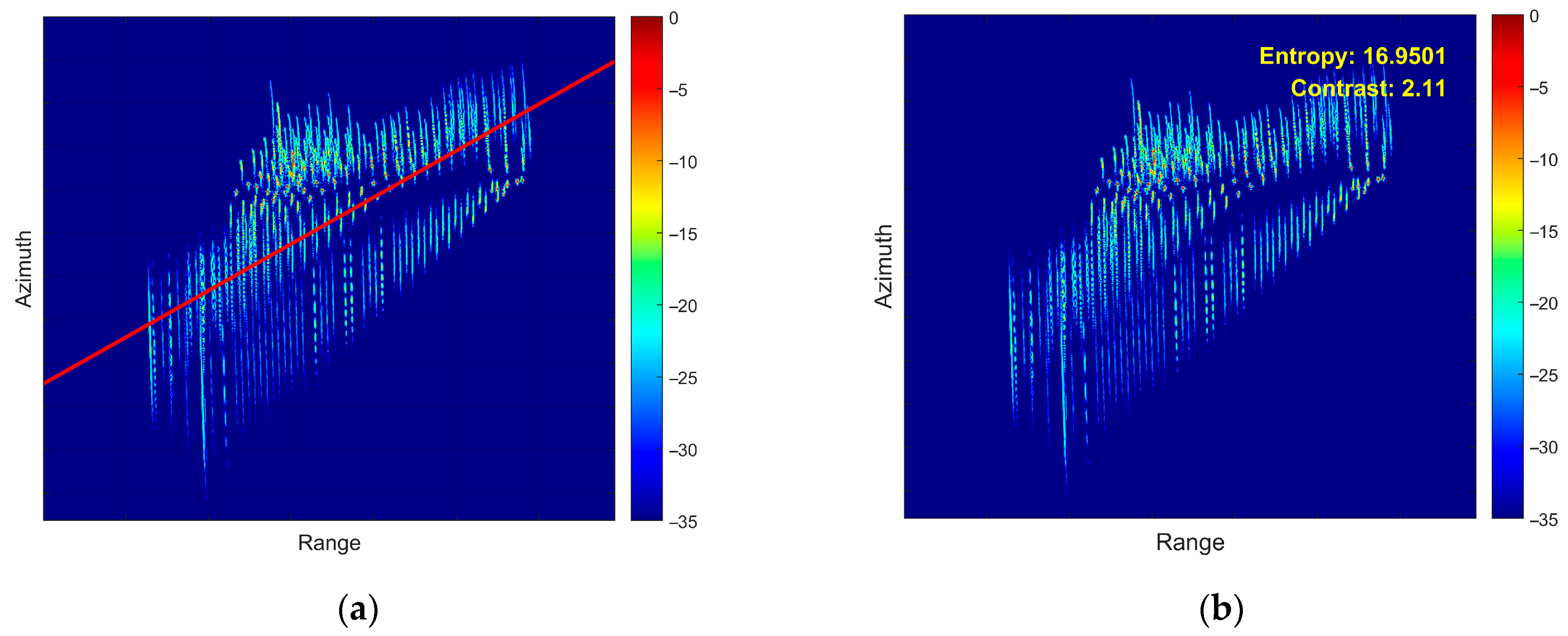

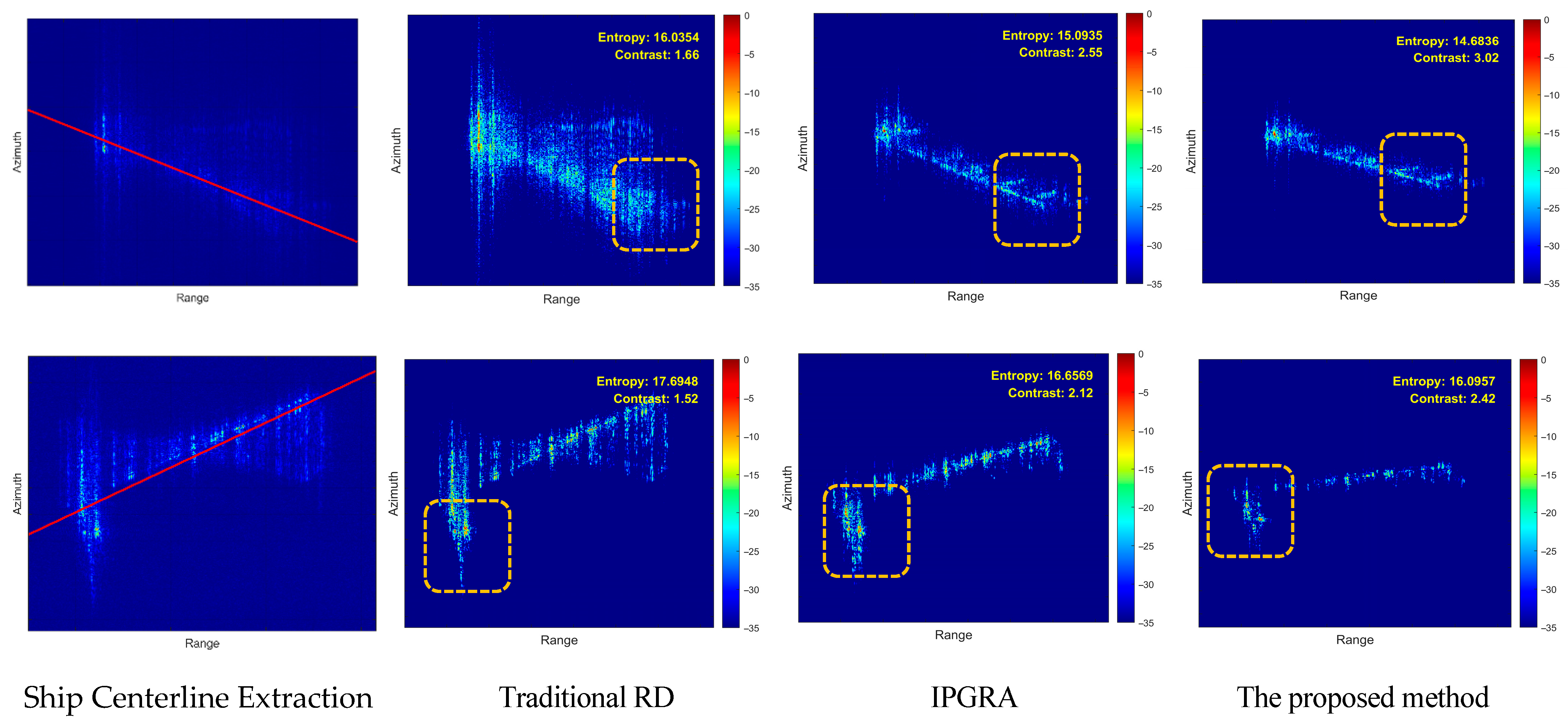

5.2. Airborne SAR Measured Data Verification

5.3. Processing Time Comparison

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, W.; Guo, Z.; Huang, P.; Tan, W.; Gao, Z. Towards efficient SAR ship detection: Multi-level feature fusion and lightweight network design. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y. An efficient range-Doppler domain ISAR imaging approach for rapidly spinning targets. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 58, 2670–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tello, M.; Lopez-Martinez, C.; Mallorqui, J.J. Automatic Vessel Monitoring with Single and Multidimensional SAR Images in the Wavelet Domain. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2006, 61, 260–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Qi, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H. Effect of 6-DOF oscillation of ship target on SAR imaging. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Sun, G.-C.; Xia, X.-G.; Fu, J.; Xing, M.; Bao, Z. Focusing challenges of ships with oscillatory motions and long coherent processing interval. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 6562–6572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Jin, Y.-Q. A study of ship rotation effects on SAR image. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 3132–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasih, A.R.; Rigling, B.D.; Moses, R.L. Analysis of target rotation and translation in SAR imagery. In Proceedings of the SPIE Defense, Security, and Sensing, Orlando, FL, USA, 11–15 May 2009; Zelnio, E.G., Garber, F.D., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2009; p. 73370F. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Song, H.; He, W. A novel method for refocusing moving ships in SAR images via ISAR technique. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Zhang, H.; Deng, Y.; Ai, Z.; Du, J. Increase the coherent processing interval for SAR focusing of maneuvering ships by data resampling. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5210322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Gu, Z.; Xu, Z.; Xiao, S. ISAR Image Transform via Joint Intrapulse and Interpulse Periodic-Coded Phase Modulation. Remote Sens. 2025, 25, 28788–28799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.Y.; Wang, L.; Yu, Y.S.; Wu, R. Robust ISAR range alignment via minimizing the entropy of the average range profile. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2009, 6, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, D.G.; Eichel, P.H.; Ghiglia, D.C.; Jakowatz, C.V., Jr. Phase gradient autofocus—A robust tool for high-resolution SAR phase correction. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 1994, 30, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samec, P.; Kulpa, Z.S. Coherent MapDrift technique. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2010, 48, 1505–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.C.; Yang, W.; Wang, P.B.; Li, Z.F.; Li, Y. A modified PGA for spaceborne SAR scintillation compensation based on the weighted maximum likelihood estimator and data division. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 3938–3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H. A Hybrid SAR/ISAR Approach for Refocusing Maritime Moving Targets with the GF-3 SAR Satellite. Sensors 2020, 20, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, J.L. Range-Doppler imaging of rotating objects. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 1980, 16, 23–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, Y. ISAR imaging of non-uniformly rotating target via range-instantaneous-Doppler-derivatives algorithm. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2014, 7, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.C.; Williams, W.J. Kernel design for reduced interference distributions. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 1992, 40, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.I.; Williams, W.J. Improved time-frequency representation of multicomponent signals using exponential kernels. IEEE Trans. Acoust. Speech Signal Process. 1989, 37, 862–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zibulski, M.; Zeevi, Y.Y. Oversampling in the Gabor scheme. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 1993, 41, 2679–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, M.; Wu, R.; Li, Y.; Bao, Z. New ISAR imaging algorithm based on modified Wigner-Ville distribution. IET Radar Sonar Navig. 2009, 3, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Q. Rotation parameters estimation and cross-range scaling research for range instantaneous Doppler ISAR images. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 7010–7020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddar, A.; Ogawa, Y.; Walton, E.K. Estimating the time delay and frequency decay parameter of scattering components using a modified MUSIC algorithm. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 1994, 42, 1412–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-S.; Wu, R.; Li, J. Complex ISAR imaging of maneuvering targets via the Capon estimator. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 1999, 47, 1262–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yardibi, T.; Li, J.; Stoica, P.; Xue, M.; Baggeroer, A.B. Source localization and sensing: A nonparametric iterative adaptive approach based on weighted least squares. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2010, 46, 425–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.C. ISAR imaging for three-dimensional rotation targets based on adaptive Chirplet decomposition. Multidimens. Syst. Signal Process. 2010, 21, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhan, M.; Su, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Liao, G. Performances analysis of coherently integrated CPF for LFM signal under low SNR and its application to ground moving target imaging. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 6402–6419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Liu, Z. ISAR imaging for low-Earth-orbit target based on coherent integrated smoothed generalized cubic phase function. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 58, 1205–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yan, L.; Li, D.; Liu, H.; Zhang, C. A novel ISAR imaging method for maneuvering target based on AM-QFM model under low SNR environment. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 140499–140512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cao, R.; Huang, X. ISAR imaging of maneuvering target based on the estimation of time varying amplitude with Gaussian window. IEEE Sens. J. 2019, 19, 11180–11191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, H.; Djurovic, I.; Himed, B. Integrated cubic phase function for linear FM signal analysis. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2010, 46, 963–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, J. A novel ISAR imaging algorithm for nonuniformly rotating target. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 26 September–2 October 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 4562–4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Q. Deep learning-based enhanced ISAR-RID imaging method. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Li, J. High-resolution ISAR imaging method for maneuvering targets based on hybrid transformer network. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2023, 59, 5123–5137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Zhang, H.; Deng, Y.; Dong, S. Iteration phase gradient resample autofocus: A real-time and robust algorithm for focusing maneuvering ships in SAR images. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2025, 61, 14082–14099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, W.; Liu, C. Long coherent processing intervals for ISAR imaging: Combined complex signal kurtosis and data resampling. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Zhang, H.; Deng, Y.; Dong, S. Azimuth envelope alignment for focusing maneuvering ships in SAR images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5207815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jian, M. Optimal time selection for ISAR imaging of ship target via novel approach of centerline extraction with RANSAC algorithm. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 9987–10005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehmas, R.; Jylhä, J.; Välilä, M.; Vihonen, J.; Visa, A. Data-driven motion compensation techniques for noncooperative ISAR imaging. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2018, 54, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, R.P.; DiPietro, R.C.; Fante, R.L. SAR imaging of moving targets. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 1999, 35, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Carrier frequency | 9.6 GHz |

| Signal bandwidth | 300 MHz |

| Range sampling frequency | 600 MHz |

| Pulse repetition frequency | 600 Hz |

| CPI | About 1.5 s |

| Platform Altitude | 6000 m |

| Platform Speed | 60 m/s |

| Ship Motion Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Orientation | 45° |

| Roll period | 8 s |

| Pitch period | - |

| Yaw period | - |

| Roll amplitude | 6° |

| Pitch amplitude | - |

| Yaw amplitude | - |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Orientation | |

| Roll period | 8 s |

| Pitch period | 10 s |

| Yaw period | 12 s |

| Roll amplitude | |

| Pitch amplitude | |

| Yaw amplitude |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Carrier frequency | X |

| Range sampling frequency | 500 MHz |

| Range resolution | 0.5 m |

| Pulse repetition frequency | 1200 Hz |

| Platform speed | 50 m/s |

| CPI | About 2.5 s |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Carrier frequency | Ku |

| Range sampling frequency | 500 MHz |

| Range resolution | 0.5 m |

| Pulse repetition frequency | 1500 Hz |

| Platform Speed | 65 m/s |

| CPI | About 2 s |

| Method Name | Processing Time (ms) |

|---|---|

| IPGRA | 1009 |

| IIPGRA | 1900 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ruan, W.; Liu, C.; Wang, D. Robust ISAR Autofocus for Maneuvering Ships Using Centerline-Driven Adaptive Partitioning and Resampling. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010105

Ruan W, Liu C, Wang D. Robust ISAR Autofocus for Maneuvering Ships Using Centerline-Driven Adaptive Partitioning and Resampling. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):105. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010105

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuan, Wenao, Chang Liu, and Dahu Wang. 2026. "Robust ISAR Autofocus for Maneuvering Ships Using Centerline-Driven Adaptive Partitioning and Resampling" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010105

APA StyleRuan, W., Liu, C., & Wang, D. (2026). Robust ISAR Autofocus for Maneuvering Ships Using Centerline-Driven Adaptive Partitioning and Resampling. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010105