1. Introduction

Water vapor is one of the most dynamic constituents of the atmosphere, with approximately 99% concentrated in the troposphere. Variations in tropospheric water vapor are closely linked to cloud formation and dissipation, as well as precipitation processes such as rainfall and snowfall, playing a crucial role in their occurrence and evolution [

1,

2,

3]. Monitoring the spatiotemporal variations in water vapor is essential for accurately predicting precipitation timing, location, and intensity [

4,

5,

6]. Moreover, it contributes to improving numerical weather forecasting, enhancing our understanding of the Earth’s climate system, assessing the impacts of climate change [

7], and supporting applications in hydrological disaster prevention, mitigation, and water resource management.

The spatiotemporal variations in water vapor are highly complex, making accurate monitoring and forecasting challenging. Precipitable water vapor (PWV) is commonly used to quantify atmospheric water vapor content, representing the total amount of precipitation that would result if all the water vapor in a vertical air column were condensed [

8,

9]. Traditional PWV detection methods include radiosondes (RSs) [

10,

11], microwave radiometers [

12], remote sensing [

13,

14,

15], and reanalysis datasets [

16,

17]. RSs carried by weather balloons provide direct vertical atmospheric profiling, offering high-accuracy PWV measurements that serve as reference data for validating other retrieval methods. However, radiosondes are single-use consumables with high operational costs, limited station distribution, and relatively low spatiotemporal resolution, restricting their applicability in large-scale water vapor monitoring. With advancements in remote sensing technology, the satellite-based retrieval of PWV has become widely utilized [

18]. Remote sensing imagery, which is easily accessible, leverages spectral absorption differences across various sensor channels to derive continuous, large-scale distributions of PWV with high spatial resolution. More recently, the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) has emerged as a promising data source for PWV retrieval, offering point-based observations with high temporal resolution and minimal susceptibility to weather conditions [

19,

20]. The BeiDou Navigation Satellite System (BDS), developed and independently operated by China, has gained significant attention for its reliability and performance in PWV retrieval. Ground-based BDS-PWV estimation using the Precise Point Positioning (PPP) method achieves retrieval accuracy comparable to that of the Global Positioning System (GPS), with the mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean square error (RMSE) remaining at the millimeter level, typically within the range of 1–3 mm [

21,

22], thereby meeting the accuracy requirements for PWV monitoring. In particularly, BDS demonstrates high correlation, low bias, and superior performance in real-time processing and B2b signal applications [

23,

24].

The Moderate-resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), mounted on the Terra and Aqua satellites, provides stable data acquisition with a long-term observational record spanning from 2000 to the present. As one of the most widely used data sources in current research, MODIS is capable of retrieving column-integrated precipitable water vapor content from the near-surface to the upper troposphere. However, the reliability of MODIS water vapor products remains moderate, with significant retrieval biases, particularly under cloudy and rainy conditions, where underestimation is commonly observed [

25]. The accuracy of MOD05 water vapor products exhibits notable regional variations, with significant deviations observed in certain areas. In China, northern regions demonstrate relatively better accuracy, whereas southern regions, especially the southeastern areas, suffer from larger biases and lower accuracy, with RMSE exceeding 10 mm [

26]. This systematic underestimation is primarily attributed to cloud interference and limitations of the near-infrared retrieval algorithm, which only yields valid retrievals over near-infrared reflective surfaces [

27]. Despite the advantages of MODIS data in terms of long-term observation and spatial continuity, its accuracy varies significantly, particularly in southern China [

28]. Therefore, integrating or correcting MODIS data with higher-accuracy water vapor datasets is necessary to obtain high-accuracy, spatially continuous water vapor information. This has become a key research focus in the field of multi-source data fusion for PWV retrieval.

To obtain high-accuracy and spatially continuous PWV data, it is essential to systematically analyze the error characteristics of MODIS-PWV data and to develop robust fusion frameworks that integrate them with high-accuracy PWV observations. At the data processing level, various spatial interpolation methods such as Kriging interpolation and inverse distance weighting (IDW) have been widely used to reconcile the scale mismatch between discrete GNSS station observations and gridded MODIS pixels, thereby enabling unified correction modeling [

29,

30,

31,

32]. In terms of modeling strategies, both linear and nonlinear approaches have been proposed to account for the spatiotemporal heterogeneity between GNSS-PWV and MODIS-PWV, often considering seasonal [

33] and regional differences [

34,

35]. This combined strategy of spatial registration and dynamic modeling has demonstrated robustness across various regions, including China and Australia [

36]. In recent years, machine learning algorithms, with their strong nonlinear modeling and feature-learning capabilities, have provided a powerful paradigm for multi-source water vapor data fusion. Algorithms such as multiple regression [

37,

38], random forests [

39], neural networks [

40,

41,

42], and XGBoost [

43] have been successfully applied to extract complex relationships among multi-source datasets, substantially improving retrieval accuracy. Xiong et al. [

44] compared the performance of random forests, generalized neural networks, and BP neural networks in water vapor data fusion at monthly and annual scales, with results indicating that random forests achieved the highest accuracy. Wang et al. [

33] integrated BP neural networks, random forests, and multiple linear regression models using MODIS NIR and TIR band information, referencing high-accuracy GNSS-PWV, to enhance water vapor retrieval accuracy under various weather conditions. Xu et al. [

45] fused MODIS NIR band data, ERA5-PWV, and GNSS-PWV using BP neural networks, significantly improving PWV retrieval accuracy in high-latitude regions, with RMSE reductions of 81.38% compared to radiosonde data. Numerous studies have demonstrated that constructing intelligent fusion models using GNSS-PWV as a reference, combined with machine learning algorithms, not only effectively mitigates the spatial and temporal resolution limitations of MODIS-PWV but also provides a more comprehensive reference for water vapor monitoring during extreme weather events. In addition, most existing studies focus on monthly or annual scale of PWV fusion, with insufficient attention given to higher temporal resolutions, such as at the daily scale, which is critical for meteorological monitoring and hydrological applications.

Moreover, many previous studies often construct unified fusion models over the entire period, which improves accuracy to some extent but fails to capture the seasonal non-stationarity and residual variability of water vapor. This limitation reduces adaptability to complex wet season when water vapor variability is high and extreme errors are more likely. Motivated by these limitations, this study aims to develop a daily scale, season-aware PWV fusion framework that explicitly accounts for dry-wet seasonal non-stationarity. By integrating high-accuracy PWV derived from the BeiDou satellite system with MODIS-PWV using a seasonal random forest strategy, the proposed approach dynamically adjusts model parameters through seasonal partitioning. This design preserves the spatial continuity of MODIS-PWV while leveraging the accuracy and temporal stability of BDS-PWV, ultimately improving fusion accuracy, robustness and spatial generalization ability across contrasting climatic conditions.

3. Results

3.1. Performance Evaluation of Multi-Source PWV Products

3.1.1. Evaluation of MODIS-PWV

Based on RS-PWV data, our study quantitatively evaluates the accuracy characteristics of MODIS-PWV over Hunan Province. A spatiotemporal matching strategy was employed for data alignment. In the spatial dimension, a 3 × 3 pixels window centered on the MODIS pixel corresponding to the radiosonde station was extracted, and the average value was matched with RS-PWV. In terms of temporal matching, the satellite overpass time does not coincide with the radiosonde observation time. In this study, the instantaneous MODIS-PWV values at the satellite overpass were associated with the RS-PWV observations at UTC 00:00. Although this introduces a potential temporal offset of several hours, its impact is considered limited, as PWV generally varies smoothly over short time intervals outside rapidly evolving convective conditions, making this matching strategy reasonable and widely adopted in satellite PWV validation studies.

Figure 3 illustrates the correlation and residual distribution between the two datasets at the RSCS, RSHH, and RSCZ. Correlation analysis reveals weak relationships between MODIS-PWV and RS-PWV at the three radiosonde stations, with correlation coefficients of 0.4012, 0.3839, and 0.4223, respectively, indicating consistently low levels of consistency. This indicates substantial discrepancies between MODIS-PWV and RS-PWV, with MODIS-PWV generally showing a systematic underestimation. Further analysis of the residual time series distribution reveals pronounced seasonal variation in the differences between MODIS-PWV and RS-PWV, with large fluctuations in residual throughout the year. Notably, significant residuals are observed during wet season, with residuals even exceeding 60 mm, indicating that the retrieval accuracy of MODIS-PWV declines markedly under high-humidity conditions, with underestimation becoming more severe as water vapor increases.

The seasonal difference in residuals is primarily attributed to the contrasting atmospheric conditions between dry and wet seasons. During the dry season, water vapor content is relatively low and cloud interference is minimal, leading to smaller retrieval errors. In contrast, the wet season is characterized by high humidity, extensive cloud cover, and varying surface reflectance, which can interfere with remote sensing signals through cloud masking and atmospheric scattering. As a result, the stability and accuracy of MODIS-PWV decrease significantly, reflecting its high sensitivity and instability during the wet season. Further accuracy assessment results summarized in

Table 1 show that the RMSE ranges from 21.00 mm to 26.20 mm, and MAE ranges from 15.85 mm to 19.59 mm, with average RMSE and MAE values of 23.80 mm and 18.04 mm, respectively—all exceeding 15 mm, which further confirms the limited accuracy of MODIS-PWV data over Hunan Province.

Overall, these findings indicate that the applicability of MODIS-PWV in this region is subject to notable limitations, particularly during the wet season. In practical applications, it is essential to account for such seasonal biases and consider the integration of high-accuracy datasets for correction and fusion to improve the overall accuracy of water vapor retrievals.

3.1.2. Evaluation of BDS-PWV

BDS-PWV and RS-PWV are both point-based datasets; however, they differ in temporal resolution and spatial alignment. Therefore, a comparative analysis must be conducted under a unified spatiotemporal framework. To address temporal discrepancies, a time-matching strategy is implemented. Specifically, for each CORS station, the average BDS-PWV values within one hour following the radiosonde launch times are computed and compared with the corresponding RS-PWV values. This approach ensures a reasonable and consistent data alignment for validation. For spatial proximity principle, we select CORS stations located within a 40 km radius of each radiosonde site for BDS-PWV accuracy validation. The corresponding station information is provided in

Table 2.

Figure 4 presents the PWV time series for the RSCS-CSKC, RSHH-HHZF, and RSCZ-CZYX station pairs. The results indicate that the BDS-PWV retrievals exhibit a high degree of consistency with the corresponding RS-PWV, demonstrating similar temporal variation trends. This strong correlation suggests that BDS-PWV effectively captures actual PWV variations, confirming the reliability of BDS-PWV retrievals. Based on the characteristics of the PWV time series, it is observed that during the wet season, the atmospheric water vapor content is relatively high, exhibiting more intense fluctuations and strong temporal variability. In contrast, during the dry season, the water vapor content is comparatively low, with smaller fluctuations.

To quantitatively evaluate the accuracy of BDS-PWV,

Table 2 provides the RMSE, MAE, and R for each validation station. The results show that the correlation coefficient (R) between BDS-PWV and RS-PWV ranges from 0.9754 to 0.9854, indicating a strong temporal consistency. The RMSE values for all stations range from 2.95 mm to 3.81 mm, while MAE values fall within 2.32 mm to 3.03 mm. The average RMSE and MAE are 3.47 mm and 2.71 mm, respectively. These results suggest that the deviation between BDS-PWV and RS-PWV is minimal, confirming the reliability of BDS-PWV for high-accuracy atmospheric water vapor retrieval. Analysis of the time series indicates that water vapor content is higher during the wet season, exhibiting larger fluctuations and strong temporal variability, whereas it is lower and more stable in the dry season.

3.2. Seasonal Dependence of MODIS-BDS PWV Relationship and Residual Characteristics

Due to significant differences in water vapor variation across months and seasons, constructing a full-season fusion model yields limited improvement for certain periods. Therefore, the daily mean BDS-PWV data are used as the target output to assess the correlation and residual characteristics of MODIS-PWV data. The results indicate that the correlation between BDS-PWV and MODIS-PWV, as well as the residual characteristics, are similar across stations, with R generally ranging from 0.40 to 0.60. This suggests a moderate positive correlation between the two datasets, although the relationship is relatively weak.

For clarity and conciseness, three stations (CDAX, YYSQ, and WCLZ) were randomly selected to demonstrate the correlation and residual distribution, as shown in

Figure 5. The results reveal substantial discrepancies between MODIS-PWV and BDS-PWV. During the dry season, the residuals generally range within ±20 mm, indicating relatively stable retrievals and smaller errors. However, in the wet season, MODIS-PWV exhibits significant underestimation, with a wider residual distribution between −60 mm and 20 mm. The results reveal clear systematic differences in water vapor retrieval accuracy between the dry and wet seasons, indicating that a unified full-period model cannot effectively capture their distinct characteristics, particularly limiting performance in the wet season. To address this, a fusion strategy based on the division of dry and wet seasons is proposed. This approach aligns with the physical mechanisms of water vapor transport and mitigates wet season underestimation bias, enabling adaptive optimization of the nonstationary features across seasons.

3.3. Fusion Model Construction

The above analysis indicates that BDS and MODIS PWV data exhibit strong nonstationary and nonlinear characteristics between dry and wet seasons. Accordingly, a random forest-based fusion strategy incorporating seasonal division is proposed. Compared with traditional linear models, the random forest algorithm can flexibly capture complex nonlinear relationships through the integration of multiple decision trees and adaptively learn seasonal variations via its splitting mechanism. Unlike neural networks, RF requires less data and simpler parameter tuning, while its feature importance analysis reveals the differential contributions of influencing factors to PWV fusion, enhancing model interpretability.

Considering the influence of season, elevation, and geographic location on the spatiotemporal distribution of PWV, we leveraged the random forest algorithm’s capability to handle diverse input features. Five parameters are selected as input features: MODIS-PWV, DOY, longitude, latitude, and elevation, while BDS-PWV serves as the reference target used to train the model. The inclusion of DOY allows capturing systematic temporal variation in PWV; longitude and latitude reflect regional water vapor gradients; elevation accounts for topographic effects on atmospheric water vapor distribution. Together, these variables enable the model to learn robust spatiotemporal variations in PWV beyond what MODIS alone can provide.

A station-based cross-validation strategy was adopted in this study. By setting a fixed random seed, the 109 HNCORS stations were randomly divided into training and independent test subsets at a ratio of 8:2, ensuring the reproducibility of the experiments. The fusion model was constructed using all samples from 87 training stations and subsequently evaluated at 22 validation stations that were completely excluded from the training process. This strategy effectively avoids spatial information leakage among stations and provides a more realistic assessment of the model’s spatial generalization ability and robustness, thereby demonstrating the reliability and regional transferability of the fusion in regions not covered by the training data. In addition, a random search strategy was employed for hyperparameter optimization of the random forest model, in which key parameters including the number of trees, maximum tree depth, minimum samples per leaf, and maximum features were systematically explored and the optimal combination was selected based on cross-validation performance. The results indicate that the maximum features and minimum samples per leaf remained at their default values, while the number of trees and maximum tree depth were the primary tuned parameters, with optimal settings of (300, 25) for the dry season and (200, 25) for the wet season, respectively.

The model was trained separately for dry and wet seasons, allowing dynamic adaptation to seasonal residual differences and achieving adaptive weight distribution across seasons. Compared with the traditional full-period static fusion model, this strategy effectively reduces the impact of extreme residuals while maintaining high correlation, enhances seasonal adaptability, improves the accuracy and stability of PWV fusion, and further strengthens the model’s spatial generalization capability in regions. The model construction framework is illustrated in

Figure 6.

3.4. Performance Evaluation of the Fusion Model

3.4.1. Validation of Fusion Model Performance Based on Independent Stations

Following the proposed fusion model construction process and data preparation principles, a random forest model was trained. The dataset was randomly divided into training and testing subsets based on the number of stations, with a total of 2975 test samples for the dry season and 3439 samples for the wet season.

To further quantitatively assess the performance of the fusion model under different seasonal conditions and to examine its capability to accommodate seasonal non-stationarity,

Figure 7 presents the prediction results of the fusion model for both the dry and wet seasons. The scatter distributions (

Figure 7a,c) indicate that, in both seasons, the fusion PWV exhibits a markedly stronger linear consistency with BDS-PWV than the original MODIS-PWV, characterized by substantially reduced dispersion and significantly enhanced correlation. During the dry season, the fusion model achieves an R

2 of 0.9617, with RMSE and MAE values of 1.67 mm and 1.21 mm, respectively, corresponding to improvements of 90.48%, 87.73%, and 88.68% relative to MODIS-PWV. In the wet season, similarly high performance is maintained, with an R

2 of 0.9587, RMSE of 2.36 mm, and MAE of 1.74 mm, representing improvements of 99.29%, 91.76%, and 92.30%, respectively. The consistently high R

2 values indicate stable predictive performance in both seasons, with slightly better accuracy during the dry season.

As shown in

Figure 7b,d, residual analysis further demonstrates the stability of the fusion results, as residuals in both seasons are concentrated near zero with relatively narrow distributions. In the dry season, 96.91% of residuals fall within ±4 mm, with only a small number exceeding ±8 mm, indicating strong reliability under relatively stable water vapor conditions, although larger fluctuations occur when PWV ranges from 10 to 30 mm. In contrast, during the wet season, 91.36% of the residuals remain within ±4 mm, while the number of extreme residuals exceeding ±8 mm increases noticeably and the distribution becomes more dispersed, particularly for PWV values between 35 and 65 mm.

3.4.2. Regional PWV Estimation and Accuracy Assessment in Hunan Province

The primary objective of constructing the daily-scale water vapor data fusion model is to generate a dataset that balances high accuracy and spatial continuity.

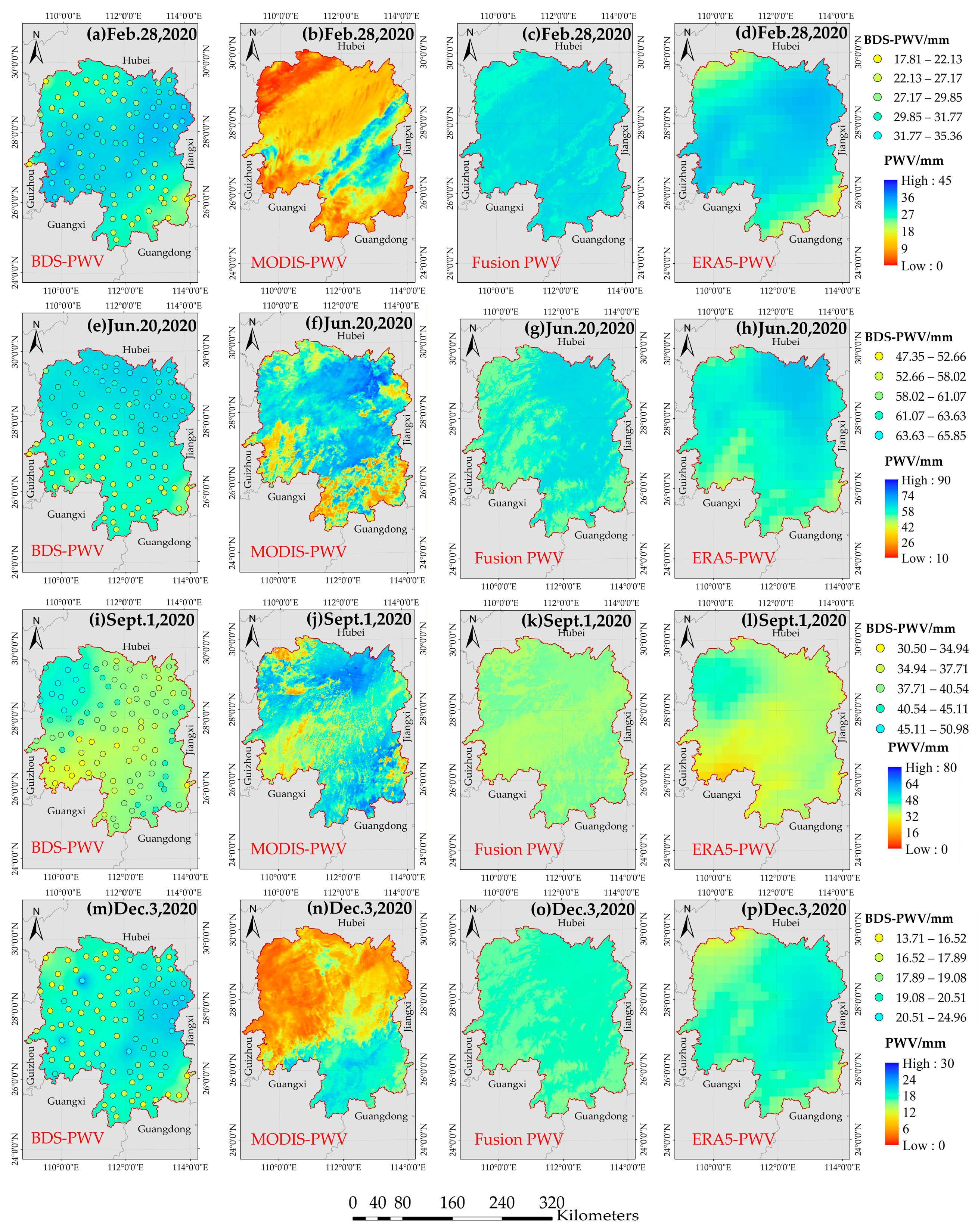

Figure 8 illustrates the spatial distribution of water vapor before and after fusion.

Figure 8a,e,i,m depict the discrete BDS-PWV observations together with the spatially continuous PWV fields derived from the inverse distance weighting (IDW) interpolation method. MODIS-PWV (

Figure 8b,f,j,n) significantly underestimates PWV, along with noisy pixel interference and spatial inconsistencies. Due to its relatively coarse spatial resolution, ERA5-PWV (

Figure 8d,h,l,p) is unable to resolve fine-scale spatial variability of PWV and is therefore used only as a reference for the overall regional distribution pattern.

In contrast, the fusion PWV (

Figure 8c,g,k,o) shows significant improvements in both numerical accuracy and spatial distribution, effectively capturing the primary spatial gradients of atmospheric water vapor over Hunan Province, particularly those associated with topographic variability. The fusion PWV demonstrates stronger large-scale spatial consistency with ERA5-PWV while revealing substantially richer spatial details. At the same time, the fusion effectively mitigates the systematic underestimation inherent in MODIS-PWV, enabling the fusion product to retain the spatial continuity of MODIS while achieving numerical consistency closer to that of BDS-PWV.

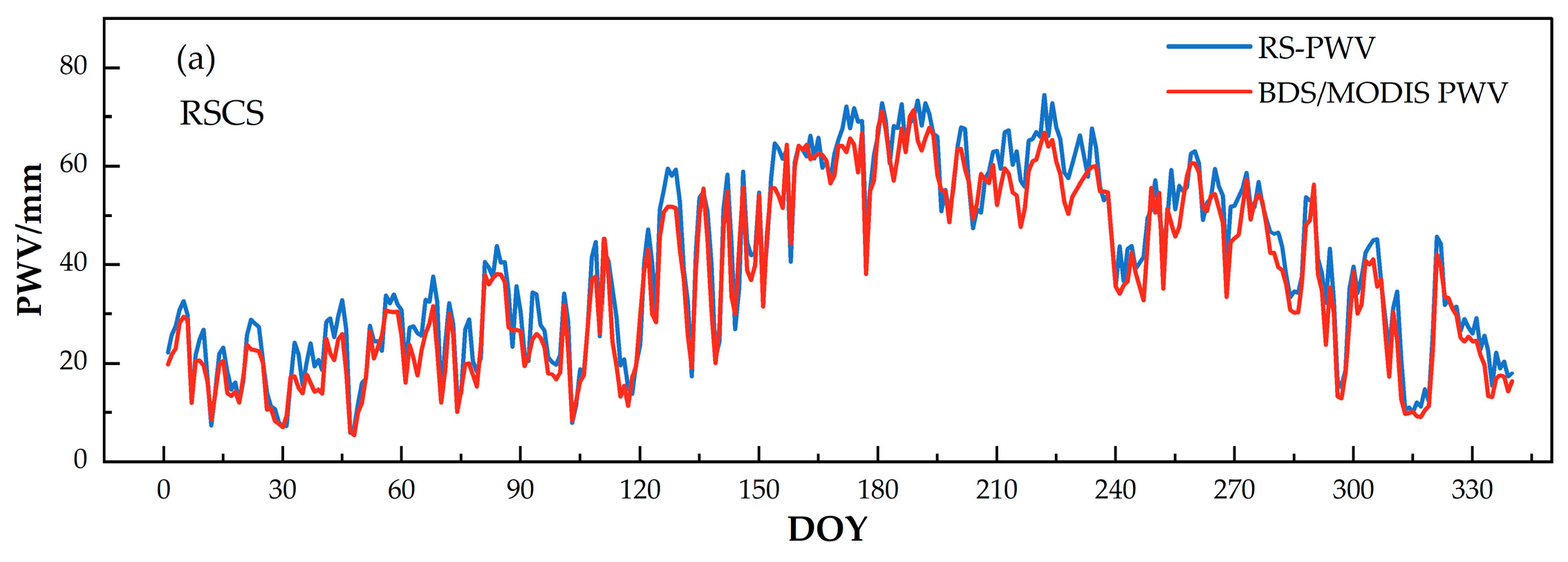

To further evaluate the accuracy of the BDS/MODIS PWV data, RS-PWV was used for validation at three radiosonde stations in Hunan Province: RSCS, RSHH, and RSCZ, as shown in

Figure 9. RS-PWV values were derived from the average of two soundings at each station. The fusion PWV closely matches RS-PWV in both temporal trends and magnitude. As summarized in

Table 3, the correlation coefficient between the BDS/MODIS PWV and RS-PWV exceeds 0.95 at all stations. The RMSE ranges from 4.63 to 4.82 mm, and the MAE ranges from 3.74 to 3.89 mm, with mean values of 4.71 mm and 3.81 mm, respectively. Compared to the original MODIS-PWV data, which had an average RMSE of 23.80 mm and MAE of 18.04 mm, the BDS/MODIS PWV data show a significant reduction in errors by 80.21% and 78.88%, respectively, demonstrating strong performance for error mitigation. Despite environmental differences among stations, the variations in RMSE and MAE remain below 0.20 mm and 0.15 mm, respectively, confirming the model’s strong generalization and spatial robustness. Furthermore, the residual reduction rate exceeding 75% across all stations further validates the feasibility and effectiveness of the random forest-based daily-scale fusion model.

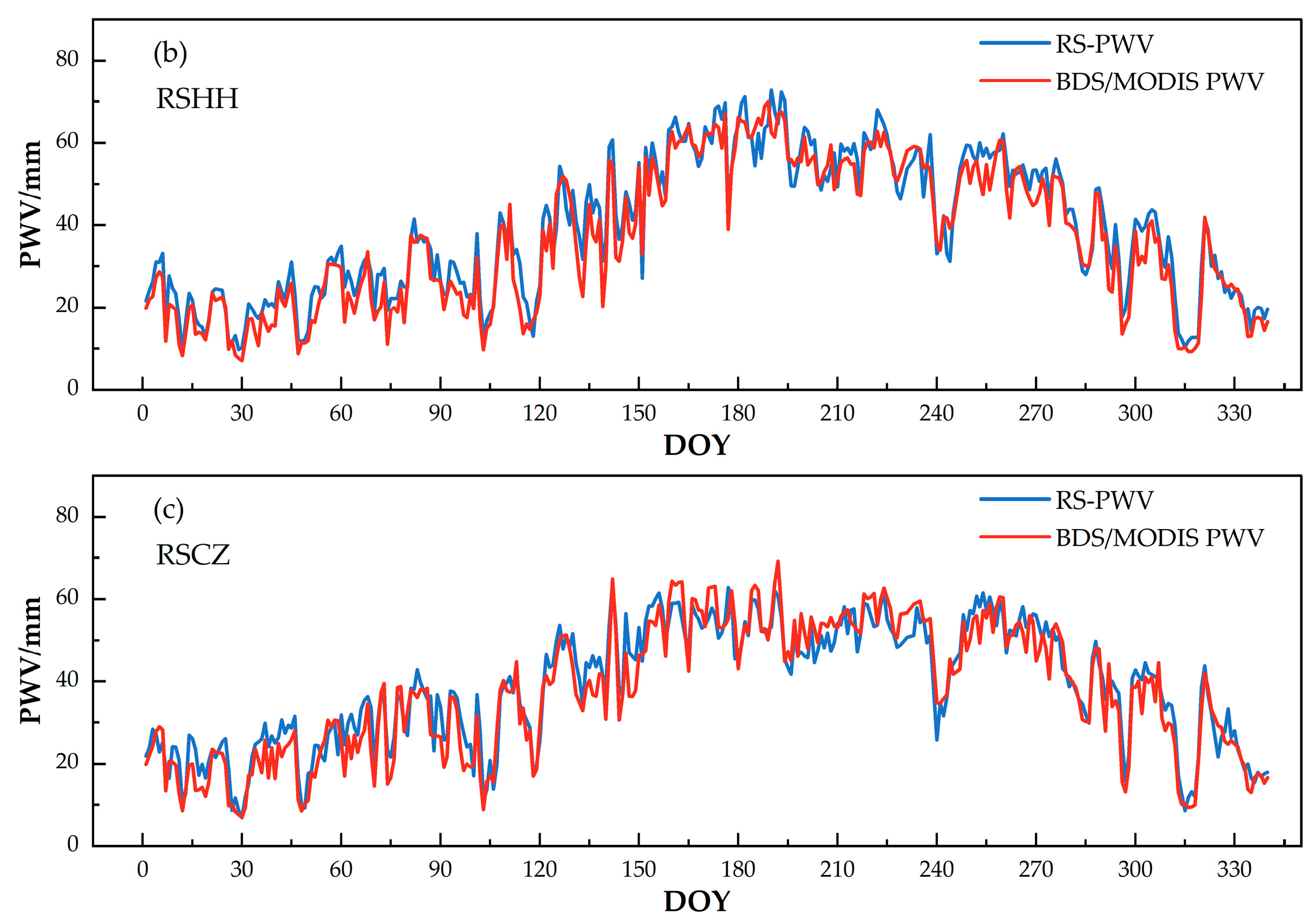

3.5. Spatiotemporal Distribution Characteristics of the Fusion PWV

The spatial distribution of PWV in Hunan Province exhibits a pattern of increasing from west to east and from north to south, as shown in

Figure 10, which aligns with the region’s climatic characteristics. A long-term analysis of the relationship between topography and PWV revealed a strong negative correlation, with a correlation coefficient of −0.8498. In mountainous and high-altitude areas, such as western Hunan, southern Hunan, and southeastern Hunan, PWV values remain relatively low due to the obstruction of moisture transport by mountain ranges. In contrast, northeastern Hunan, central Hunan, and south-central Hunan, which are characterized by lower elevation and gentler slopes, exhibit a more uniform distribution of water vapor, with relatively higher PWV values. Apart from topographic influences, water systems also significantly affect the spatial distribution of atmospheric water vapor, and serve as critical moisture sources. In Hunan Province, the water systems are primarily concentrated in the northeast, with the Xiang, Zi, Yuan, and Li Rivers traversing the entire province. Elevated water vapor levels are commonly observed in areas adjacent to the water systems, especially in topographically complex mountainous regions.

When PWV is aggregated to the monthly scale, seasonal variability becomes more clearly discernible between the dry and wet seasons. During the dry season, atmospheric water vapor remains relatively low, with peak PWV values generally ranging from 20 to 30 mm and minimum values between 10 and 20 mm. In contrast, the wet season is characterized by a pronounced increase in PWV, with peak values reaching approximately 40–60 mm and minimum values between 30 and 50 mm, highlighting the substantial seasonal contrast in regional water vapor conditions.

The temporal evolution of PWV follows a distinct seasonal cycle:

January-April: PWV shows a gradual upward trend;

May: A rapid increase in PWV is observed;

June-August: PWV reaches and maintains its peak levels, with increased regional spatial differences;

September-October: A gradual decline in PWV occurs;

November-December: PWV continues to decrease, remaining at its lowest levels.

The seasonal variations in PWV are strongly correlated with regional climatic conditions and monsoon circulation patterns. During summer, high temperatures and humidity, combined with the dominant warm and moist southeasterly monsoon, lead to an increase in water vapor content. Conversely, in winter, lower temperatures, reduced evaporation, and the prevalence of dry and cold northwesterly winds result in significantly lower PWV levels. These findings highlight the critical influence of both topography and climate on the spatial and temporal variability of atmospheric water vapor, emphasizing the necessity of incorporating such factors into high-resolution PWV modeling and prediction.

4. Discussion

Seasonal comparison indicates that the proposed fusion model effectively captures the non-stationary characteristics of atmospheric water vapor under dry and wet seasons while maintaining stable performance across varying moisture backgrounds. The fusion PWV exhibits high consistency with RS-PWV throughout the year, demonstrating that the model successfully mitigates the systematic underestimation inherent in MODIS-PWV and aligns the results with high-accuracy ground-based observations. Importantly, even under wet-season conditions characterized by high humidity, enhanced cloud coverage, and pronounced spatial heterogeneity, the fusion results exhibit only minor accuracy degradation and well-controlled extreme residuals. This confirms that explicitly accounting for seasonal variability is critical for improving model robustness under complex wet season, a limitation that is often insufficiently addressed in unified fusion models.

The improved performance can be attributed to the synergistic integration of multi-source observations while explicitly incorporating temporal and geographic controls on water vapor variability. MODIS-PWV provides high-resolution spatial information that enables the model to learn regional-scale spatial gradients, while BDS-PWV delivers accurate and temporally stable measurements that constrain numerical estimates, ensuring spatial detail is preserved without drift, particularly under high-PWV conditions. By combining these complementary characteristics within a season-aware random forest framework, the model effectively suppresses error propagation across contrasting weather conditions. Multi-station validation further confirms strong spatial generalization, indicating that the proposed approach is transferable beyond dense observation networks and suitable for application in observation-sparse regions.

Nonetheless, limitations remain. The model relies on high-accuracy BDS-PWV observations, which may limit performance in areas with sparse station coverage. Moreover, the current framework focuses on daily-scale fusion and does not fully capture sub-daily variability, which is critical for rapidly evolving atmospheric phenomena. These limitations delineate the present applicability boundary of the method rather than undermining its effectiveness. Future efforts could explore multi-sensor integration, including geostationary satellite data and high-resolution numerical weather prediction outputs, to improve temporal fidelity and extend applicability to other regions.

5. Conclusions

The high-accuracy monitoring of precipitable water vapor in both time and space is critically important for applications in meteorology and hydrology. MODIS and GNSS represent two key technologies for obtaining global PWV data; however, they exhibit significant differences in spatial and temporal resolution as well as retrieval accuracy, highlighting their strong complementarity.

We have innovatively developed a retrieval model that fuses PWV data from MODIS and BDS, incorporating DOY and geographic parameters to capture spatiotemporal variability. The proposed model was evaluated over Hunan Province using radiosonde observations and ERA5-PWV as independent reference. Validation results demonstrate that the fusion product effectively combines the high spatial resolution of MODIS with the high accuracy and temporal stability of BDS-PWV, yielding a PWV dataset with both high numerical accuracy and spatial continuity. Compared with the original MODIS-PWV, the BDS/MODIS PWV shows a substantial accuracy improvement, with correlation coefficients exceeding 0.95 relative to RS-PWV and average RMSE and MAE reduced to 4.71 mm and 3.81 mm, corresponding to reductions of 80.21% and 78.88%, respectively. The independent comparison with ERA5-PWV further confirms the spatial consistency of the fusion dataset, indicating that the proposed model effectively mitigates the systematic underestimation and weather-dependent limitations of MODIS-PWV, particularly under wet season, while preserving fine-scale spatial detail constrained by BDS-PWV.

The fusion dataset successfully captures regional-scale water vapor gradients associated with topography and hydrometeorological patterns and exhibits pronounced seasonal variability driven by monsoonal circulation. When aggregated to the monthly scale, the fusion results clearly reflect the contrast between dry and wet seasons, with PWV generally ranging from 10 to 30 mm and from 30 to 65 mm, respectively, demonstrating the model’s capability to adapt to non-stationary seasonal water vapor variations.

In summary, this study advances methodologies for retrieving atmospheric water vapor by integrating BDS and remote sensing observations, promoting the application of the BeiDou system in PWV monitoring, and provided data support for disaster prevention and mitigation applications in the meteorological and hydrological fields. The proposed framework provides a scalable foundation for future investigations of atmospheric water vapor at finer temporal resolutions and in higher-dimensional representations, thereby contributing to improved weather forecasting and climate-related studies.