Spatiotemporal Variations in Vegetation Phenology in the Qinling Mountains and Their Responses to Climate Variability

Highlights

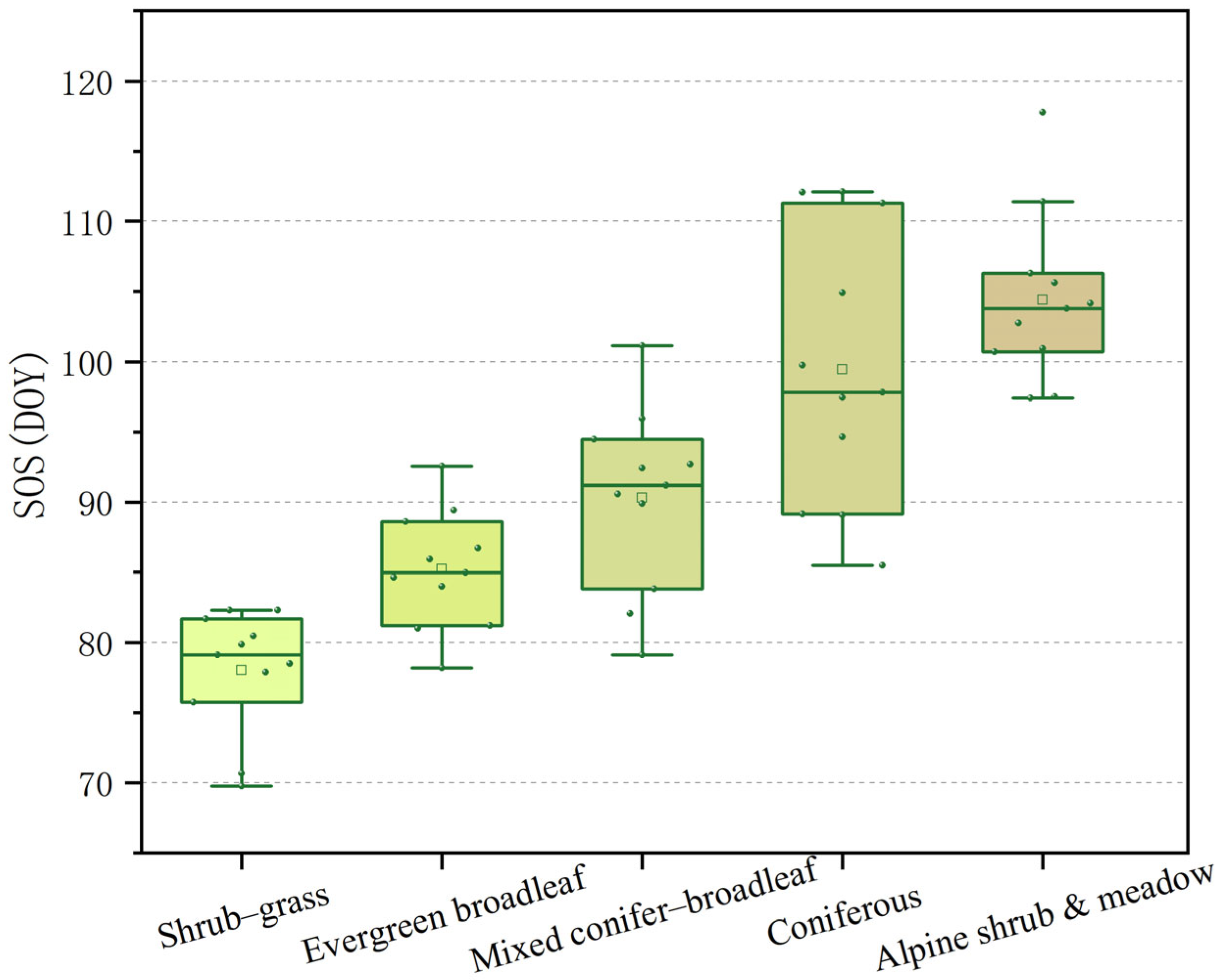

- Vegetation phenology baselines (mean SOS) are spatially constrained by altitude and vegetation type, exhibiting highly significant heterogeneity ().

- Conversely, interannual phenology trends (slopes) are statistically uniform across all vegetation types (), demonstrating a “temporal convergence” driven by a unified regional climate signal (spring temperature).

- The phenological response is asymmetric: a highly sensitive spring (SOS) is combined with a climatically insensitive autumn (EOS), revealing an “ecological buffering mechanism” that stabilizes the overall growing season length against interannual climate variability.

- The systematic ANCOVA framework successfully separates spatial heterogeneity from temporal trends, challenging the common assumption of “fragmented” phenological responses and providing a rigorous statistical approach to detect unified climate signals in complex mountain ecosystems.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Statistically test whether the baseline phenological state (i.e., mean start of season, SOS) exhibits spatial heterogeneity governed by elevation and vegetation type;

- (2)

- Determine whether interannual phenological trends (slopes) differ significantly across vegetation units or instead converge toward a common climatic driver;

- (3)

- Identify the dominant climatic factors—particularly the relative roles of temperature and precipitation—that regulate these phenological changes.

2. Materials and Methods

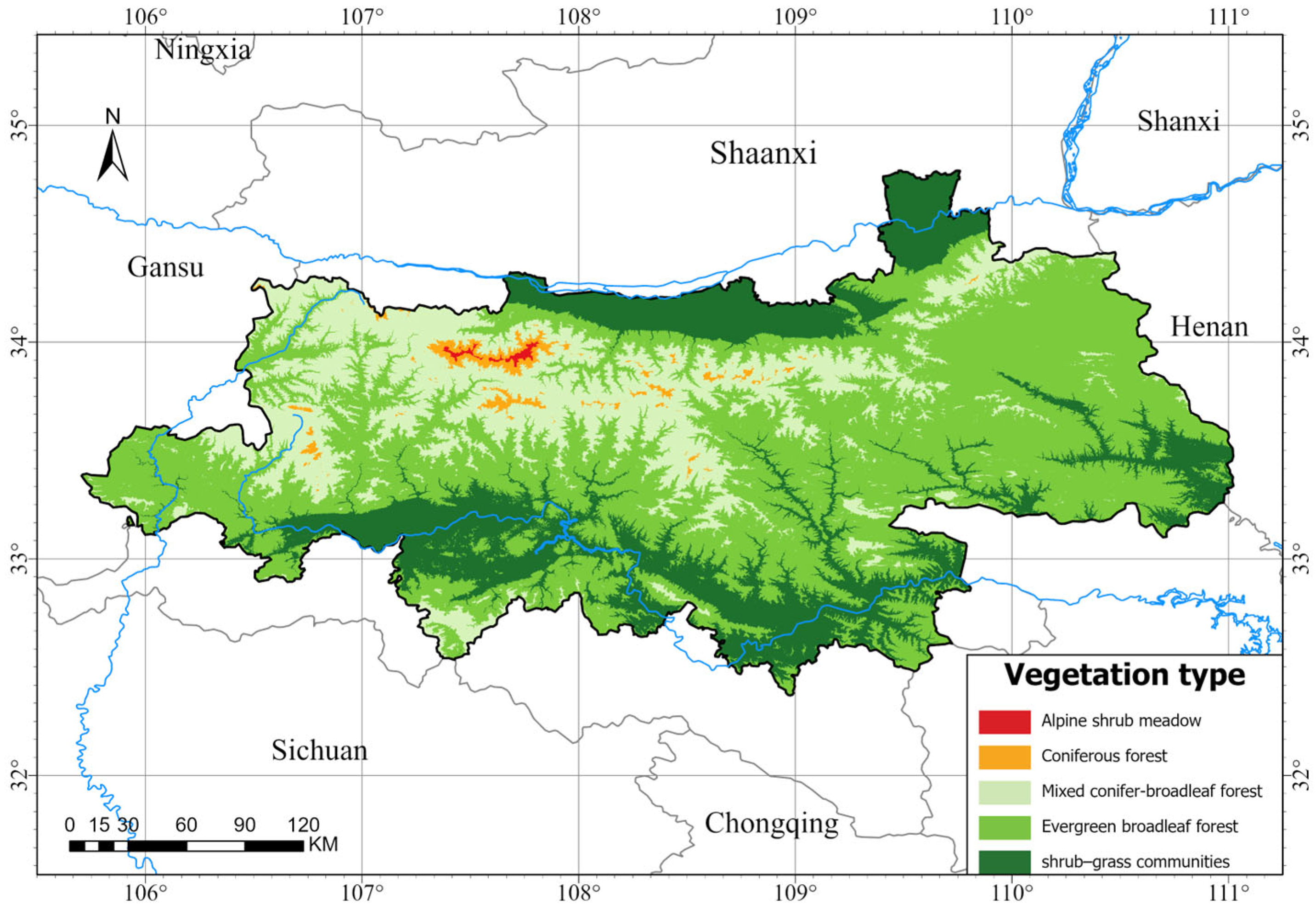

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources and Preprocessing

2.2.1. NDVI Data

2.2.2. Meteorological Data

2.2.3. Topography and Vegetation Data

2.3. Extraction of Remote Sensing Phenology and Definition of Seasonal Variables

2.3.1. NDVI Preprocessing and Smoothing

2.3.2. Phenological Metrics Extraction

2.3.3. Definition of Seasonal Climate Variables

2.4. Statistical Analyses

2.4.1. Trend Analysis

2.4.2. Pixel-Scale Climate Sensitivity Analysis

2.4.3. ANCOVA for Testing Differences Among Vegetation Types

3. Results

3.1. Data Verification and Phenological Baseline

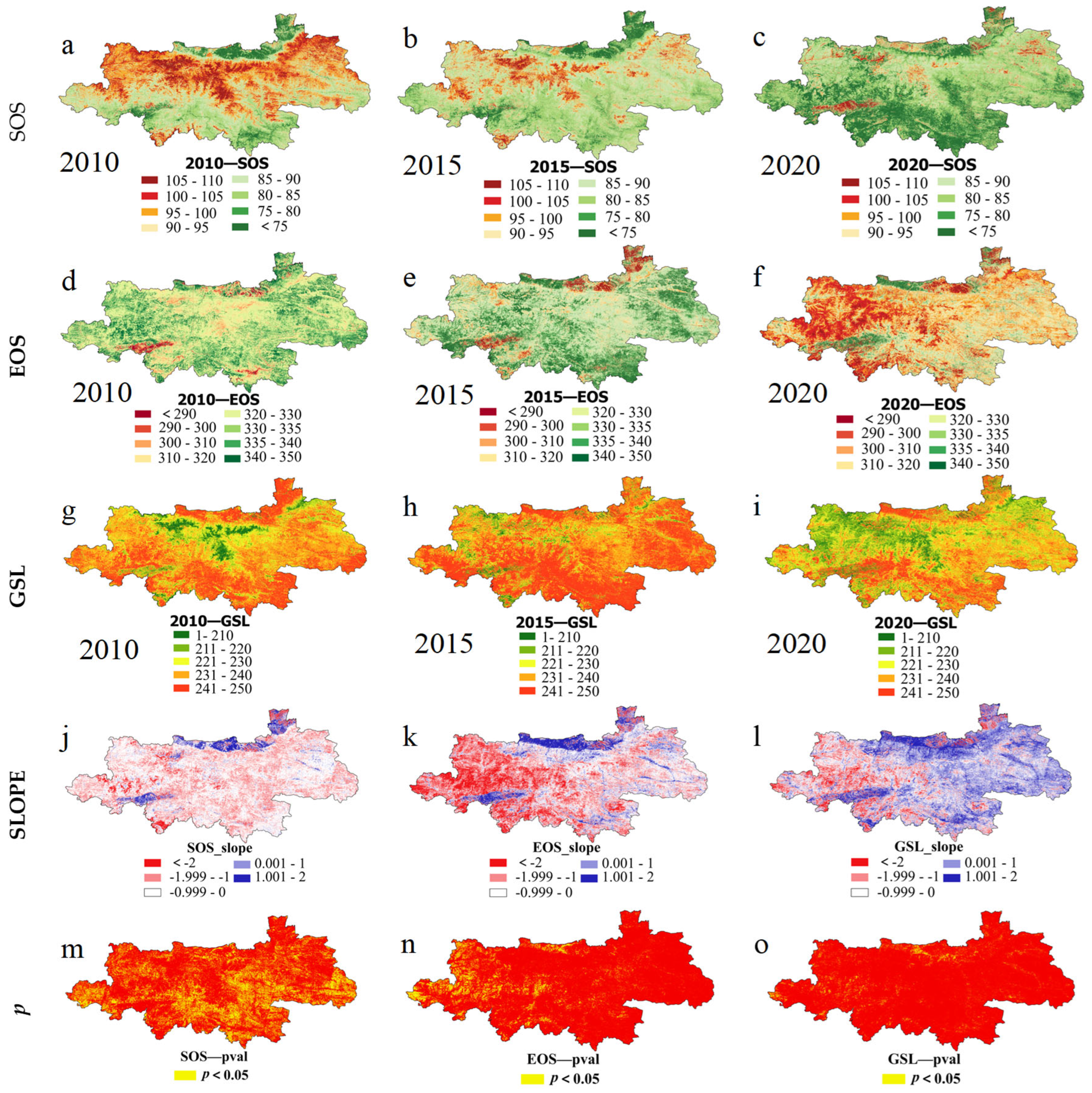

3.2. Significant Heterogeneity in Interannual Trends

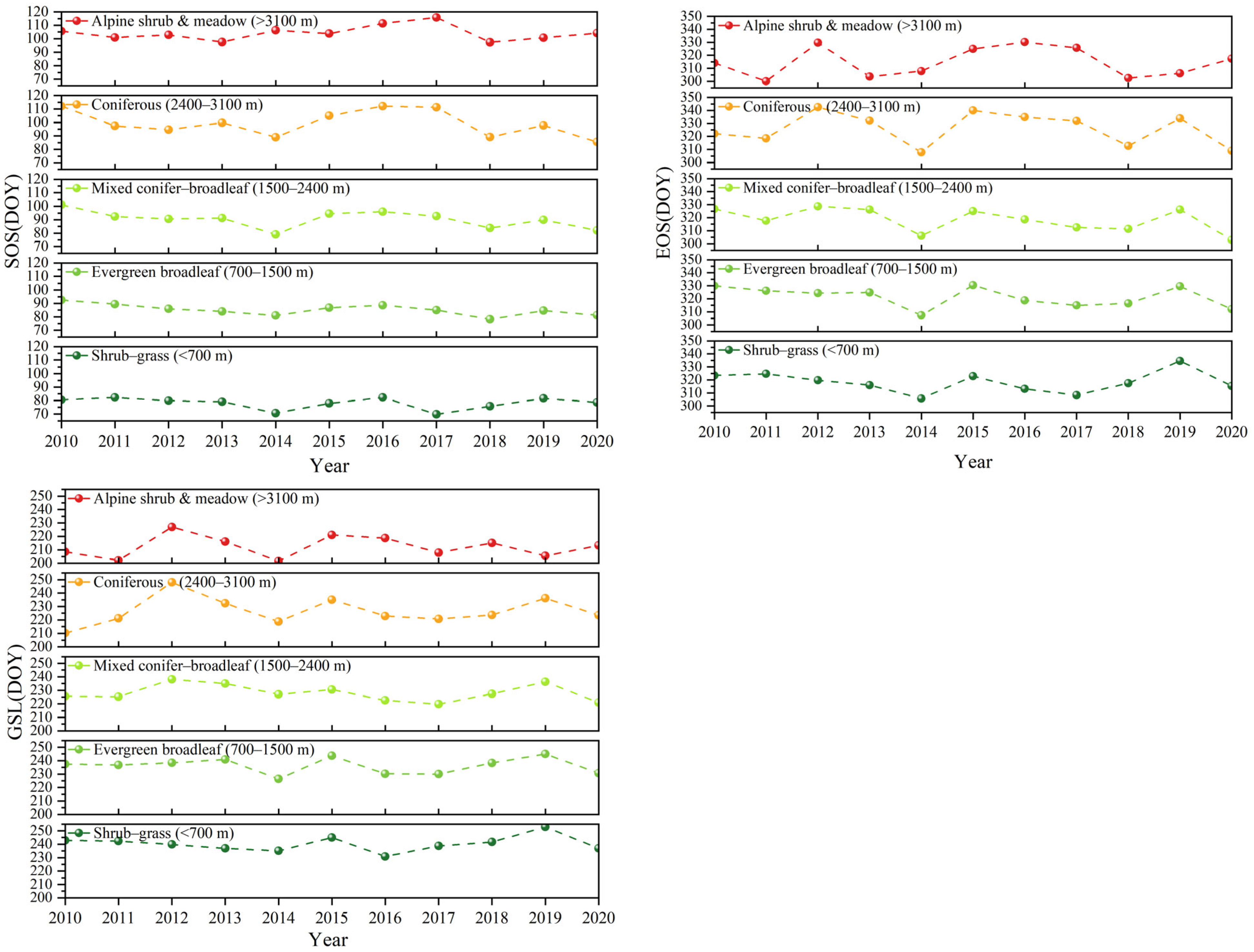

3.3. Commonalities in Interannual Trends Among Different Vegetation Types

3.4. Asymmetric Temperature Response

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| SOS | Start of Season |

| EOS | End of Season |

| GSL | Growing Season Length |

| InENVI | Integrated Environmental Variable Spatiotemporal Fusion Model |

| MODIS | Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer |

| Landsat | Landsat (series) |

| GDEM | Global Digital Elevation Model |

| HDF | Hierarchical Data Format |

| ANCOVA | Analysis of Covariance |

| CMFD | China Meteorological Forcing Dataset |

| GLT | Geometric Lookup Table |

| DN | Digital Number |

| DOY | Day of Year |

| VPD | Vapor Pressure Deficit |

| Whittaker | Whittaker smoothing (Eilers) |

| SG | Savitzky–Golay filter |

| HANTS | Harmonic ANalysis of Time Series |

| EVI | Enhanced Vegetation Index |

| PhenoCam | Phenology Camera network |

| LSP | Land Surface Phenology |

| GPP | Gross Primary Productivity |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| p-value | p-value (statistical significance) |

| slope | Trend slope |

| REA | Reliability Ensemble Averaging |

| HP—LSP | Harmonized Phenology—Land Surface Phenology |

References

- Piao, S.; Liu, Q.; Chen, A.; Janssens, I.A.; Fu, Y.; Dai, J.; Liu, L.; Lian, X.; Shen, M.; Zhu, X. Plant Phenology and Global Climate Change: Current Progresses and Challenges. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 1922–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, J.; Li, X.; Xiao, J.; Yan, X.; Li, B.; Liu, F. Vegetation Photosynthetic Phenology Dataset in Northern Terrestrial Ecosystems. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, Y.; Wu, Z.; Chen, S.; Xu, Y.; Gong, Y.; Wang, H.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Fu, Y.H. Divergent Impacts of Precipitation Regimes on Autumn Phenology in the Northern Hemisphere Mid- to High-Latitudes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2025, 52, e2025GL117589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.; Shao, Z.; Huang, X.; Zhuang, Q.; Cheng, G.; Qian, J. Climate Warming-Induced Phenology Changes Dominate Vegetation Productivity in Northern Hemisphere Ecosystems. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 151, 110326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Ma, X.; Liao, X.; Ye, H.; Yu, W.; Li, Y.; Wei, J.; Yuan, J.; Liu, Q. Linking Vegetation Phenology to Net Ecosystem Productivity: Climate Change Impacts in the Northern Hemisphere Using Satellite Data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Jiao, A.; Xu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Cong, N.; Yao, W. Divergent Responses of Vegetation Phenology and Productivity to Climate Change in Typical River Basins across Northern and Southern China. J. Plant Ecol. 2025, 18, rtaf080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Zhang, R.; Schmid, B.; Wang, H.; He, J.; Liu, J.; Liu, S.; Jian, S.; Feng, Y. A Global Synthesis of How Plants Respond to Climate Warming From Traits to Fitness. Ecol. Lett. 2025, 28, e70114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touhami, I.; Moutahir, H.; Assoul, D.; Bergaoui, K.; Aouinti, H.; Bellot, J.; Andreu, J.M. Multi-Year Monitoring Land Surface Phenology in Relation to Climatic Variables Using MODIS-NDVI Time-Series in Mediterranean Forest, Northeast Tunisia. Acta Oecologica 2022, 114, 103804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Yu, Z.; Lettenmaier, D.P.; McVicar, T.R.; Ji, X. Elevation-Dependent Response of Vegetation Dynamics to Climate Change in a Cold Mountainous Region. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 094005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Xu, G.; He, X.; Luo, D. Influences of Seasonal Soil Moisture and Temperature on Vegetation Phenology in the Qilian Mountains. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.H.; Bai, H.Y.; Ma, X.P.; Huang, X.Y.; Zhao, T. Variation characteristics and its north-south differences of the vegetation phenology by remote sensing monitoring in the Qinling Mountains during 2000–2017. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2021, 41, 1068–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, Y. Impacts of Climate, Phenology, Elevation and Their Interactions on the Net Primary Productivity of Vegetation in Yunnan, China under Global Warming. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Bai, X.; Zhao, C.; Tan, Q.; Li, Y.; Luo, G.; Wu, L.; Chen, F.; Li, C.; Ran, C.; et al. Spring Photosynthetic Phenology of Chinese Vegetation in Response to Climate Change and Its Impact on Net Prim bary Productivity. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2023, 342, 109734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, T.; Luo, X.; Ti, P.; Yang, J. Spatial Patterns of Vegetation Phenology Along the Urban–Rural Gradients in Different Local Climate Zones. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 10537–10544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Tian, F.; Jin, H.; Fensholt, R.; Feng, L.; Tagesson, T. Assessing the Elevational Synchronization in Vegetation Phenology across Northern Hemisphere Mountain Ecosystems under Global Warming. Glob. Planet. Change 2025, 252, 104903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorazimy, M.; Ronoud, G.; Yu, X.; Luoma, V.; Hyyppä, J.; Saarinen, N.; Kankare, V.; Vastaranta, M. Feasibility of Bi-Temporal Airborne Laser Scanning Data in Detecting Species-Specific Individual Tree Crown Growth of Boreal Forests. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X. Phenology of Different Types of Vegetation and Their Response to Climate Change in the Qilian Mountains, China. J. Mt. Sci. 2024, 21, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, D.L.P.; Bouachir, W.; Gervais, D.; Pureswaran, D.; Kneeshaw, D.D.; De Grandpré, L. Leveraging Artificial Intelligence for Large-Scale Plant Phenology Studies from Noisy Time-Lapse Images. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 13151–13160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Qin, Y.; Feng, G.; Meng, Q.; Cui, Y.; Song, H.; Ouyang, Y.; Liu, G. Forest Phenology Dynamics to Climate Change and Topography in a Geographic and Climate Transition Zone: The Qinling Mountains in Central China. Forests 2019, 10, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, D.; Lee, C.K.F.; Guo, Z.; Detto, M.; Alberton, B.; Morellato, P.; Nelson, B.; et al. Scale Matters: Spatial Resolution Impacts Tropical Leaf Phenology Characterized by Multi-Source Satellite Remote Sensing with an Ecological-Constrained Deep Learning Model. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 304, 114027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Xiao, F.; Du, Y.; Wang, Z.; Luo, J.; Feng, Q.; Chen, M. Application of Landsat High Spatial Resolution Phenological Synthesized Data in Mountainous Land Cover Classification. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; He, X.; Wang, D.; Zou, J.; Zeng, Z. Automatic Alpine Treeline Extraction Using High-Resolution Forest Cover Imagery. Bull. Natl. Remote Sens. 2022, 26, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, M.; Lin, T.; Zhang, J.; Jones, L.; Yao, X.; Geng, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Cao, X.; et al. Spatial Heterogeneity of Vegetation Phenology Caused by Urbanization in China Based on Remote Sensing. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 153, 110448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Friedl, M.; Richardson, A.; Pasquarella, V.; O’Keefe, J.; Bailey, A.; Thompson, J. Asymmetric Spring and Autumn Phenology Control Growing Season Length in Temperate Deciduous Forests. arXiv 2025, arXiv:10.1101/2025.10.21.683688. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Fu, Y.H.; Zeng, Z.; Huang, M.; Li, X.; Piao, S. Temperature, Precipitation, and Insolation Effects on Autumn Vegetation Phenology in Temperate China. Glob. Change Biol. 2016, 22, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Fu, Y.H.; Li, M.; Jia, Z.; Cui, Y.; Tang, J. A New Temperature–Photoperiod Coupled Phenology Module in LPJ-GUESS Model v4.1: Optimizing Estimation of Terrestrial Carbon and Water Processes. Geosci. Model. Dev. 2024, 17, 2509–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Guan, Q.; Du, Q.; Wang, Q.; Sun, W. Elevation Dependence of Vegetation Growth Stages and Carbon Sequestration Dynamics in High Mountain Ecosystems. Environ. Res. 2025, 273, 121200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Bai, H.; Zhai, D.; Gao, S.; Huang, X.; Meng, Q.; He, Y. Vegetation Phenological Changes in the Qinling Mountains from 1964 to 2015 under Climate Change. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2017, 37, 7882–7893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Peng, Q.; Shen, R.; Xu, W.; Qin, Z.; Lin, S.; Ha, S.; Kong, D.; Yuan, W. Long-Term Reconstructed Vegetation Index Dataset in China from Fused MODIS and Landsat Data. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Peng, Q.; Shen, R.; Yuan, W.; Xu, W.; Qin, W.; Lin, S.; Kong, D. A 30m fused InENVI NDVI dataset from 2001 to 2020 in China. 2025. Available online: https://www.scidb.cn/en/detail?dataSetId=93f8ef4ea76045f5b9025e6a1f1f99ab (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Sisheber, B.; Marshall, M.; Mengistu, D.; Nelson, A. Tracking Crop Phenology in a Highly Dynamic Landscape with Knowledge-Based Landsat–MODIS Data Fusion. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 106, 102670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Yang, K.; Li, X.; Tang, W.; Shao, C.; Jiang, Y.; Ding, B. China Meteorological Forcing Dataset, version 2.0 (1951–2024); National Tibetan Plateau Data Center: Beijing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Yang, K.; Tang, W.; Lu, H.; Qin, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, X. The First High-Resolution Meteorological Forcing Dataset for Land Process Studies over China. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tachikawa, T.; Hato, M.; Kaku, M.; Iwasaki, A. Characteristics of ASTER GDEM Version 2. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–29 July 2011; pp. 3657–3660. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Ren, C.; Li, Y.; Yue, W.; Wei, Z.; Song, X.; Zhang, X.; Yin, A.; Lin, X. Using Enhanced Gap-Filling and Whittaker Smoothing to Reconstruct High Spatiotemporal Resolution NDVI Time Series Based on Landsat 8, Sentinel-2, and MODIS Imagery. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.A.; de Beurs, K.M.; Didan, K.; Inouye, D.W.; Richardson, A.D.; Jensen, O.P.; O’keefe, J.; Zhang, G.; Nemani, R.R.; van Leeuwen, W.J.; et al. Intercomparison, Interpretation, And Assessment of Spring Phenology in North America Estimated from Remote Sensing for 1982–2006. Glob. Change Biol. 2009, 15, 2335–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, P.K. Estimates of the Regression Coefficient Based on Kendall’s Tau. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1968, 63, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Winter, J.C.F.; Gosling, S.D.; Potter, J. Comparing the Pearson and Spearman Correlation Coefficients Across Distributions and Sample Sizes: A Tutorial Using Simulations and Empirical Data. Psychol. Methods 2016, 21, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, A. GLM Approaches to Related Measures Designs. In Anova and Ancova; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Bognor Regis, UK, 2011; pp. 139–169. ISBN 978-1-118-49168-3. [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford, A. The GLM Approach to ANCOVA. In Anova and Ancova; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Bognor Regis, UK, 2011; pp. 215–234. ISBN 978-1-118-49168-3. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Liu, X.; Ge, W.; Ni, X.; Ma, W.; Lu, Q.; Xing, X. Specific Drivers and Responses to Land Surface Phenology of Different Vegetation Types in the Qinling Mountains, Central China. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y. Analysis of Vegetation Dynamics in the Qinling-Daba Mountains Region from MODIS Time Series Data. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 129, 108029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Ma, X.; Xie, M.; Bai, H. Effect of Altitude and Topography on Vegetation Phenological Changes in the Niubeiliang Nature Reserve of Qinling Mountains, China. Forests 2022, 13, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haoming, X.I.A.; Ainong, L.I.; Wei, Z.; Jinhu, B.; Guangbin, L.E.I. Spatiotemporal Variations of Forest Phenology in the Qinling Zone Based on Remote Sensing Monitoring, 2001–2010. Prog. Geogr. 2015, 34, 1297–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Bai, H.; He, Y.; Qin, J. The Vegetation Remote Sensing Phenology of Qinling Mountains Based on NDVI and It‘s Response to Temperature: Taking Within the Territory of Shaanxi as An Example. Geogr. Sci. 2015, 35, 1616–1621. [Google Scholar]

- Zohner, C.M.; Renner, S.S.; Sebald, V.; Crowther, T.W. How Changes in Spring and Autumn Phenology Translate into Growth-Experimental Evidence of Asymmetric Effects. J. Ecol. 2021, 109, 2717–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.-G.; Ma, Q.; Rossi, S.; Biondi, F.; Deslauriers, A.; Fonti, P.; Liang, E.; Mäkinen, H.; Oberhuber, W.; Rathgeber, C.B.K.; et al. Photoperiod and Temperature as Dominant Environmental Drivers Triggering Secondary Growth Resumption in Northern Hemisphere Conifers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 20645–20652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Z.; Ge, W.; Guo, J.; Liu, J. Satellite Remote Sensing of Vegetation Phenology: Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 217, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Liu, J.; Liu, M.; Zhu, W.; Atzberger, C.; Lv, X.; Dong, Z. Quantitative Assessment of the Spatial Scale Effects of the Vegetation Phenology in the Qinling Mountains. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Huang, X.; Bi, J. An Overview of Remote Sensing for Mountain Vegetation and Snow Cover. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Liu, Q.; Liao, X.; Ye, H.; Li, Y.; Ma, X. Refined Analysis of Vegetation Phenology Changes and Driving Forces in High Latitude Altitude Regions of the Northern Hemisphere: Insights from High Temporal Resolution MODIS Products. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.H.; Zhao, H.; Piao, S.; Peaucelle, M.; Peng, S.; Zhou, G.; Ciais, P.; Huang, M.; Menzel, A.; Peñuelas, J.; et al. Declining Global Warming Effects on the Phenology of Spring Leaf Unfolding. Nature 2015, 526, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.; Zhang, H.; Guo, X.; Shan, Y.; Ying, H.; Rihan, W.; Li, H.; Han, Y. Asymmetric Effects of Daytime and Nighttime Warming on Boreal Forest Spring Phenology. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Peng, J.; Ciais, P.; Peñuelas, J.; Wang, H.; Beguería, S.; Andrew Black, T.; Jassal, R.S.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, W.; et al. Increased Drought Effects on the Phenology of Autumn Leaf Senescence. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 943–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Tang, Y.; Chen, J. Plant Phenological Synchrony Increases under Rapid Within-Spring Warming. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobert, F.; Löw, J.; Schwieder, M.; Gocht, A.; Schlund, M.; Hostert, P.; Erasmi, S. A Deep Learning Approach for Deriving Winter Wheat Phenology from Optical and SAR Time Series at Field Level. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 298, 113800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Dai, J.; Wang, H.; Alatalo, J.M.; Liu, W.; Hao, Y.; Ge, Q. Mapping 24 Woody Plant Species Phenology and Ground Forest Phenology over China from 1951 to 2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Bevacqua, E.; Chen, C.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Myneni, R.B.; Wu, X.; Xu, C.-Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zscheischler, J. Regional Asymmetry in the Response of Global Vegetation Growth to Springtime Compound Climate Events. Commun. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | VI | Data Source | Spatial | Temporal | Method | SOS | EOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qinling Mountains [41] | NDVI | MODIS | 1 km | 16 d | Savitzky–Golay | 83–121 d | 290–300 d |

| Qinling–Daba Mountains [42] | NDVI | MODIS | 250 m | 16 d | Linear regression analysis | 80–134 d | 275–315 d |

| Qinling-Niubeiliang | NDVI | MODIS | 250 m | 8 d | Threshold | 115–140 d | 260–300 d |

| Qinling Mountains [43] | EVI | MODIS | 250 m | 16 d | Savitzky–Golay | 73–105 d | —— |

| Qinling Mountains [19] | EVI | MODIS | 500 m | 8 d | HANTS | 81–120 d | 260–310 d |

| Qinling–Daba Mountains [11] | NDVI | MODIS | 250 m | 8 d | Max-ratio | 70–130 d | 270–310 d |

| Qinling Mountains [44] | NDVI | MODIS | 500 m | 8 d | Max-ratio HANTS | 81~120 d | 270~311 d |

| Qinling Mountains [45] | NDVI | MODIS | 250 m | 10 d | Dynamic Threshold Method | 120~130 d | 300~325 d |

| Effect | F | p-Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetation | 22.21 | <0.001 | Significant difference among vegetation types |

| Year | 0.10 | 0.754 | No temporal trend |

| Vegetation × Year | 0.57 | 0.685 | No differential temporal trend among vegetation types |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, H.; Ao, J.; Liang, J.; Zhang, M.; Feng, Z.; Wang, Z. Spatiotemporal Variations in Vegetation Phenology in the Qinling Mountains and Their Responses to Climate Variability. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 4051. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244051

Li H, Ao J, Liang J, Zhang M, Feng Z, Wang Z. Spatiotemporal Variations in Vegetation Phenology in the Qinling Mountains and Their Responses to Climate Variability. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):4051. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244051

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Huan, Jiao Ao, Jiahua Liang, Mingjuan Zhang, Zhongke Feng, and Zhichao Wang. 2025. "Spatiotemporal Variations in Vegetation Phenology in the Qinling Mountains and Their Responses to Climate Variability" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 4051. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244051

APA StyleLi, H., Ao, J., Liang, J., Zhang, M., Feng, Z., & Wang, Z. (2025). Spatiotemporal Variations in Vegetation Phenology in the Qinling Mountains and Their Responses to Climate Variability. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 4051. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244051