Advancing Soil Erosion Mapping in Active Agricultural Lands Using Machine Learning and SHAP Analysis

Highlights

- Random Forest and LightGBM models effectively captured the spatial variability of soil erosion susceptibility in loess-covered agricultural lands, demonstrating the utility of machine learning for mapping environmental hazards.

- Shapley Additive Explanation (SHAP) summary and main effect analyses revealed that slope, land use/land cover (LULC), and Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) are the dominant drivers of erosion, providing interpretable insights into the mechanisms influencing soil loss.

- Combining remote sensing data with interpretable machine learning enables more informed, location-specific soil conservation and land management strategies.

- The study highlights that even gentle slopes with intensive cultivation are highly prone to erosion, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions and sustainable agricultural planning.

Abstract

1. Introduction

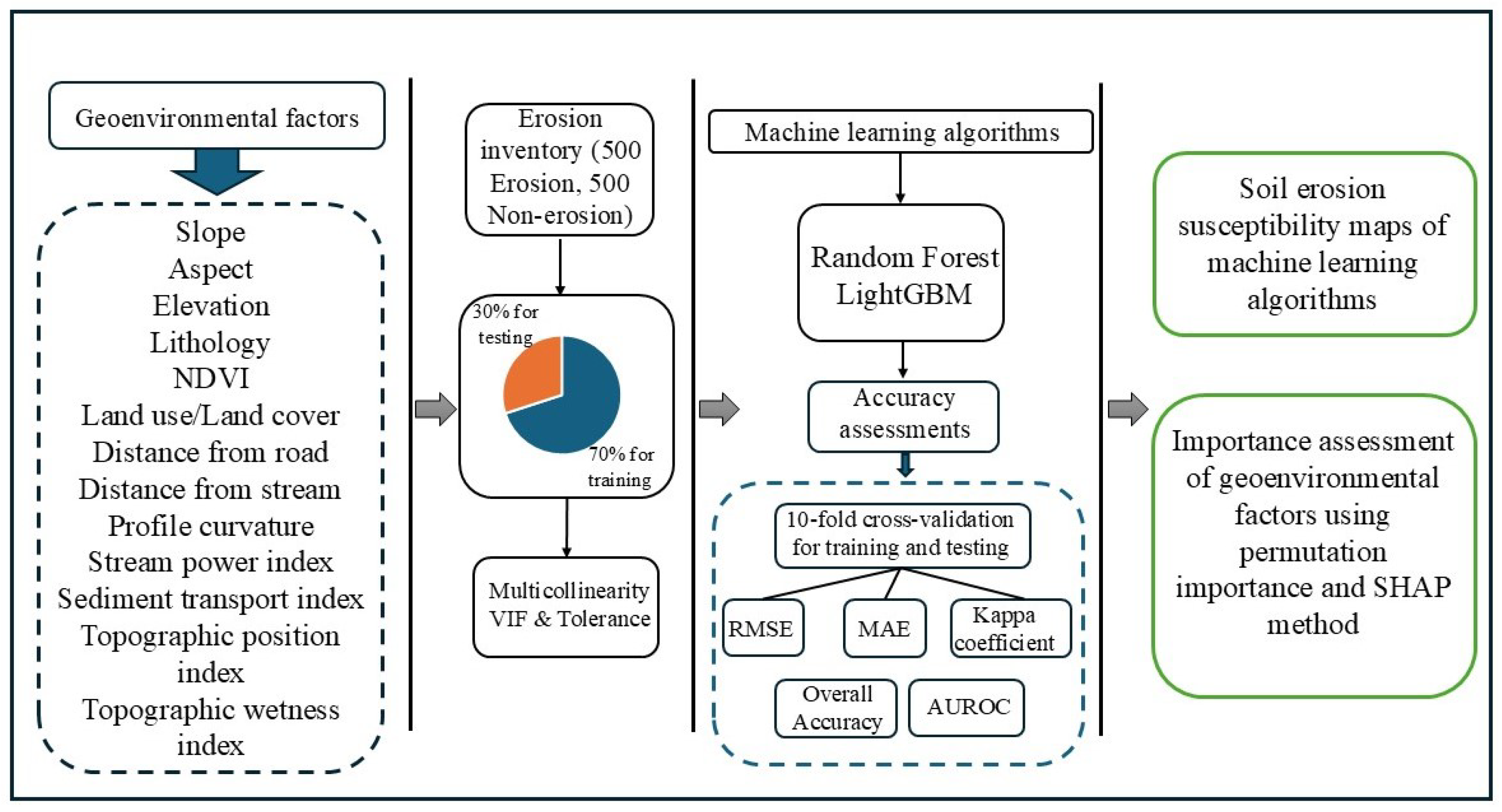

2. Material and Method

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Methodology and Data Sources

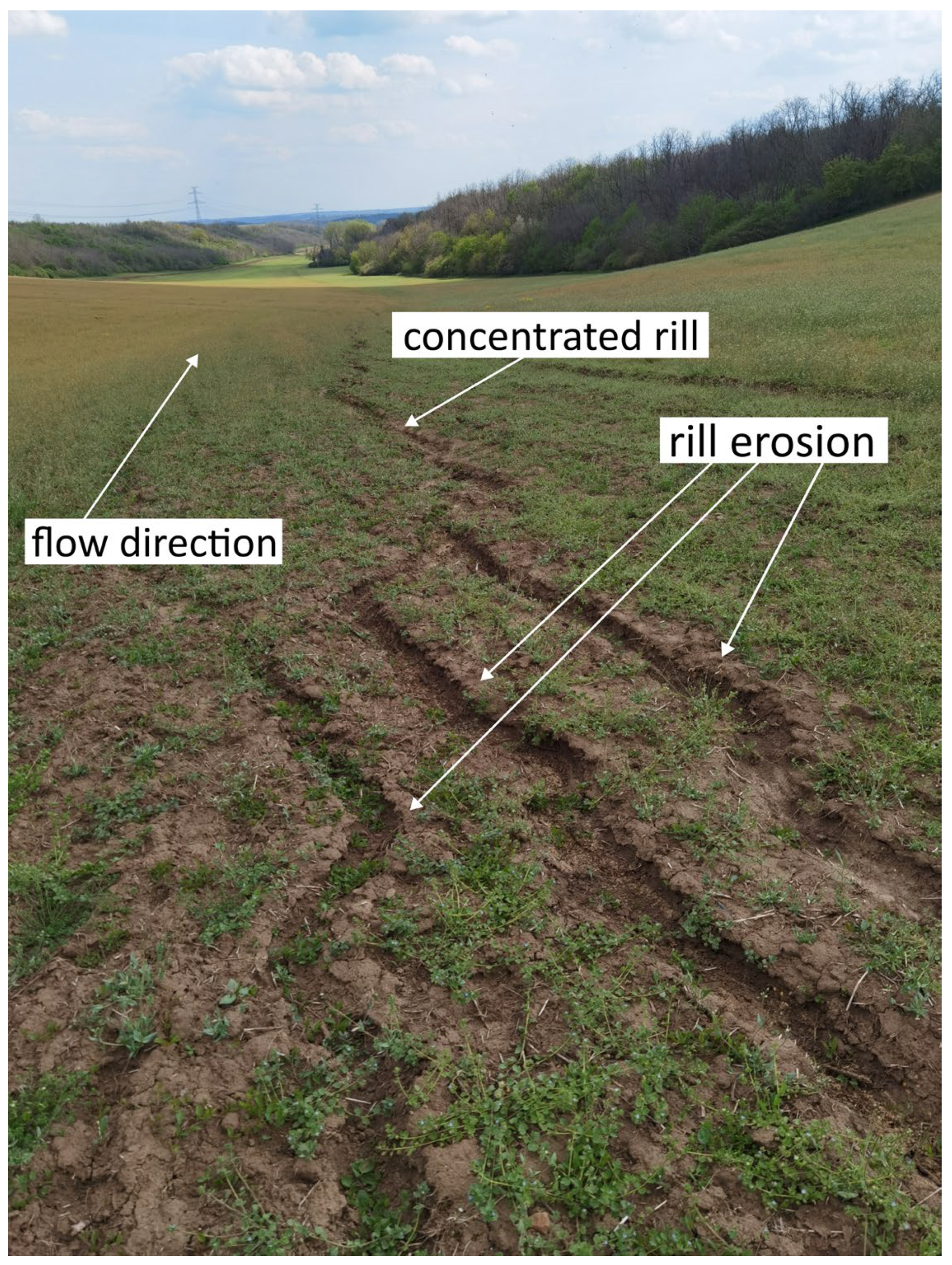

2.3. Integration of Field Survey and Remote Sensing for Soil Erosion Inventory

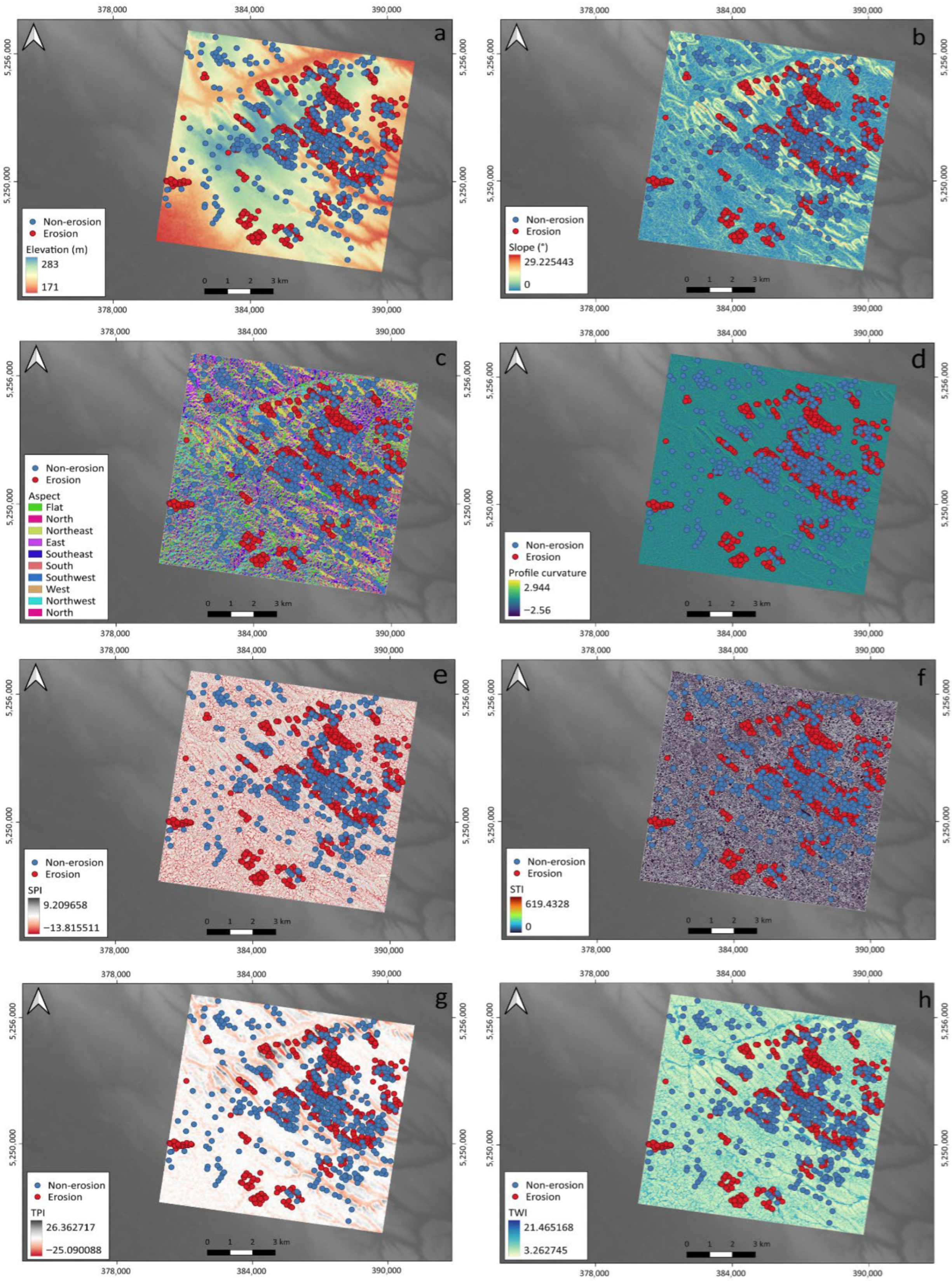

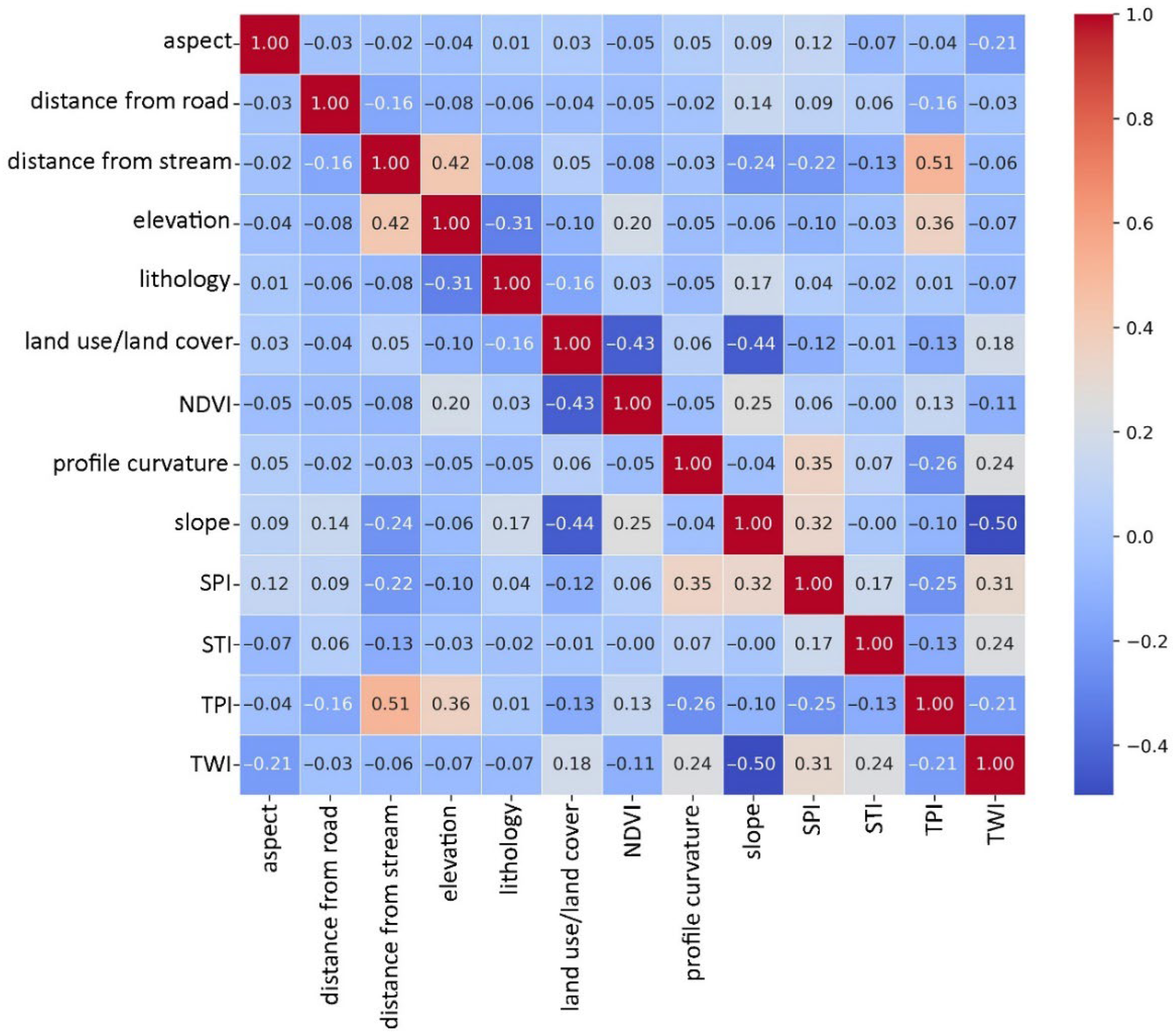

2.4. Geoenvironmental Factors Influencing Soil Erosion Susceptibility

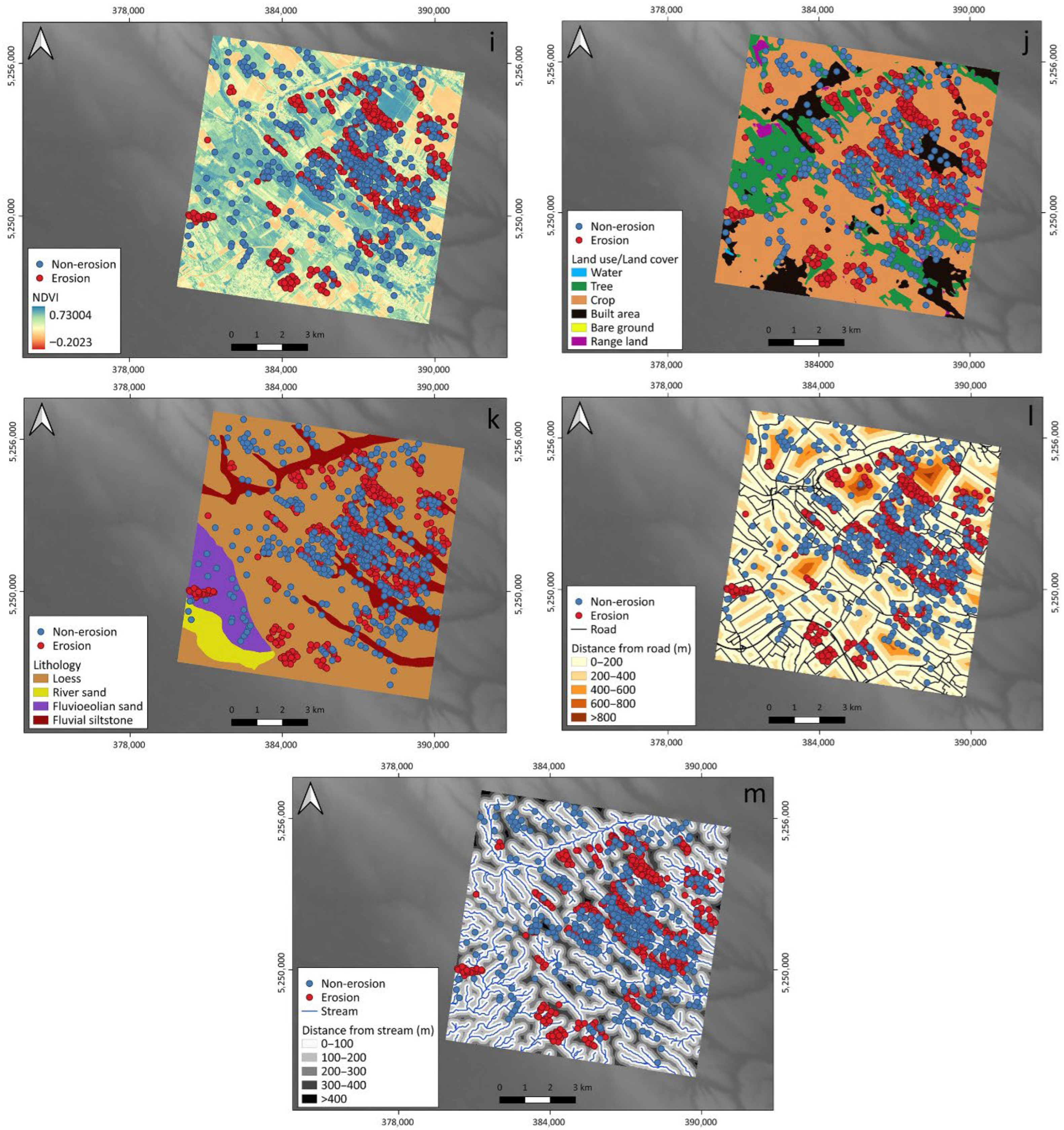

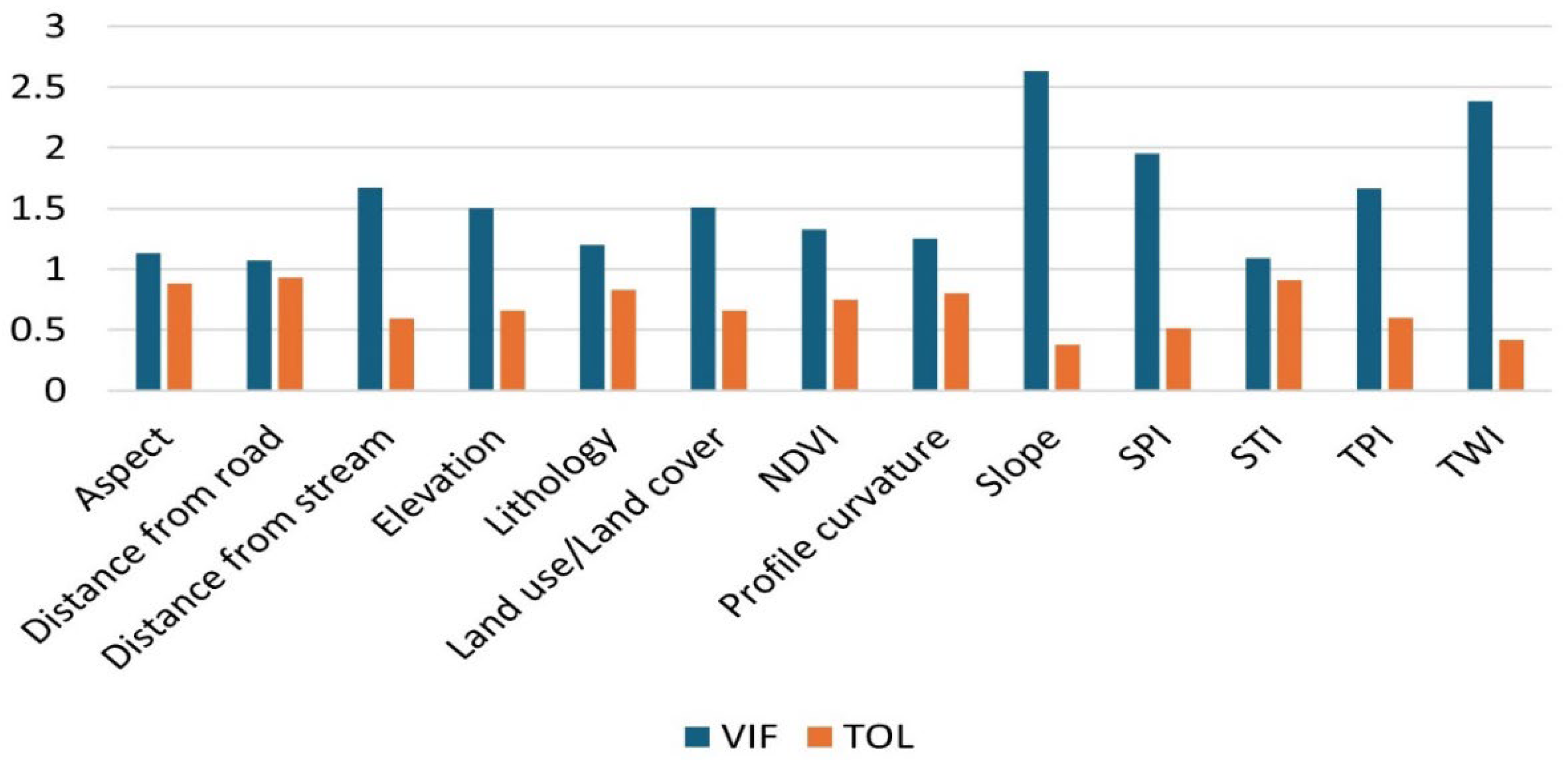

2.5. Multicollinearity Analysis

3. Machine Learning Algorithms

3.1. Random Forest

3.2. Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM)

3.3. Model Performance Evaluation

3.4. Geoenvironmental Factors’ Importance Evaluation

4. Results

4.1. Correlation Analysis

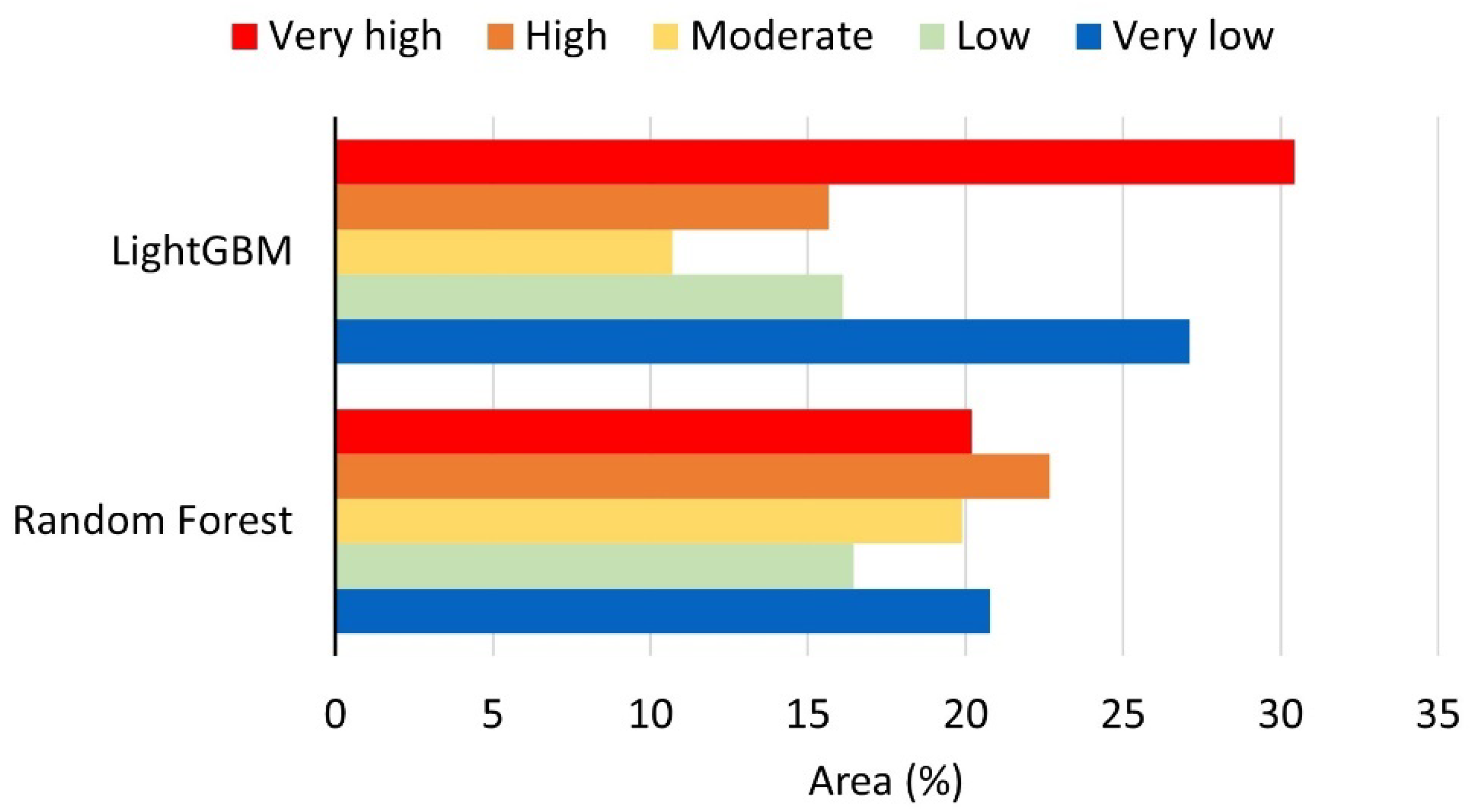

4.2. Soil Erosion Susceptibility Mapping and Spatial Variability

4.3. Spatial Consistency and Models’ Discrepancies

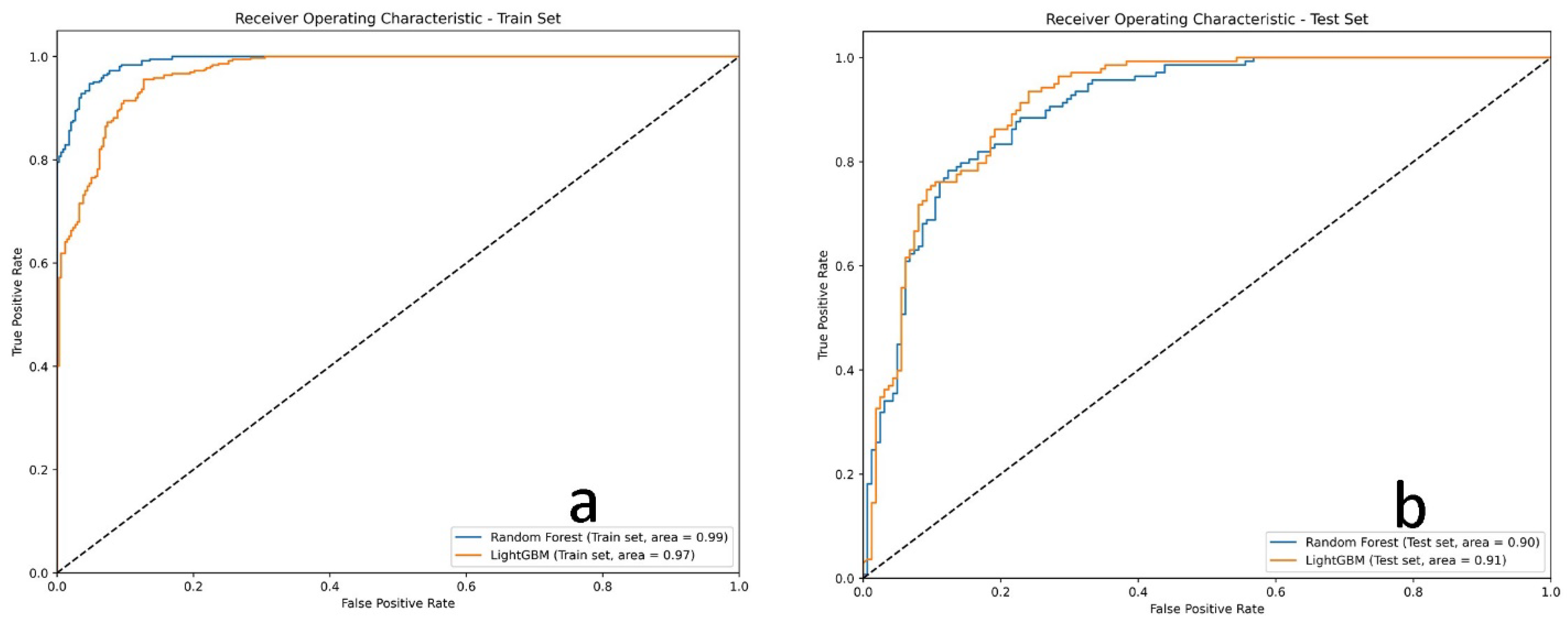

4.4. Performance Assessment of Random Forest and LightGBM

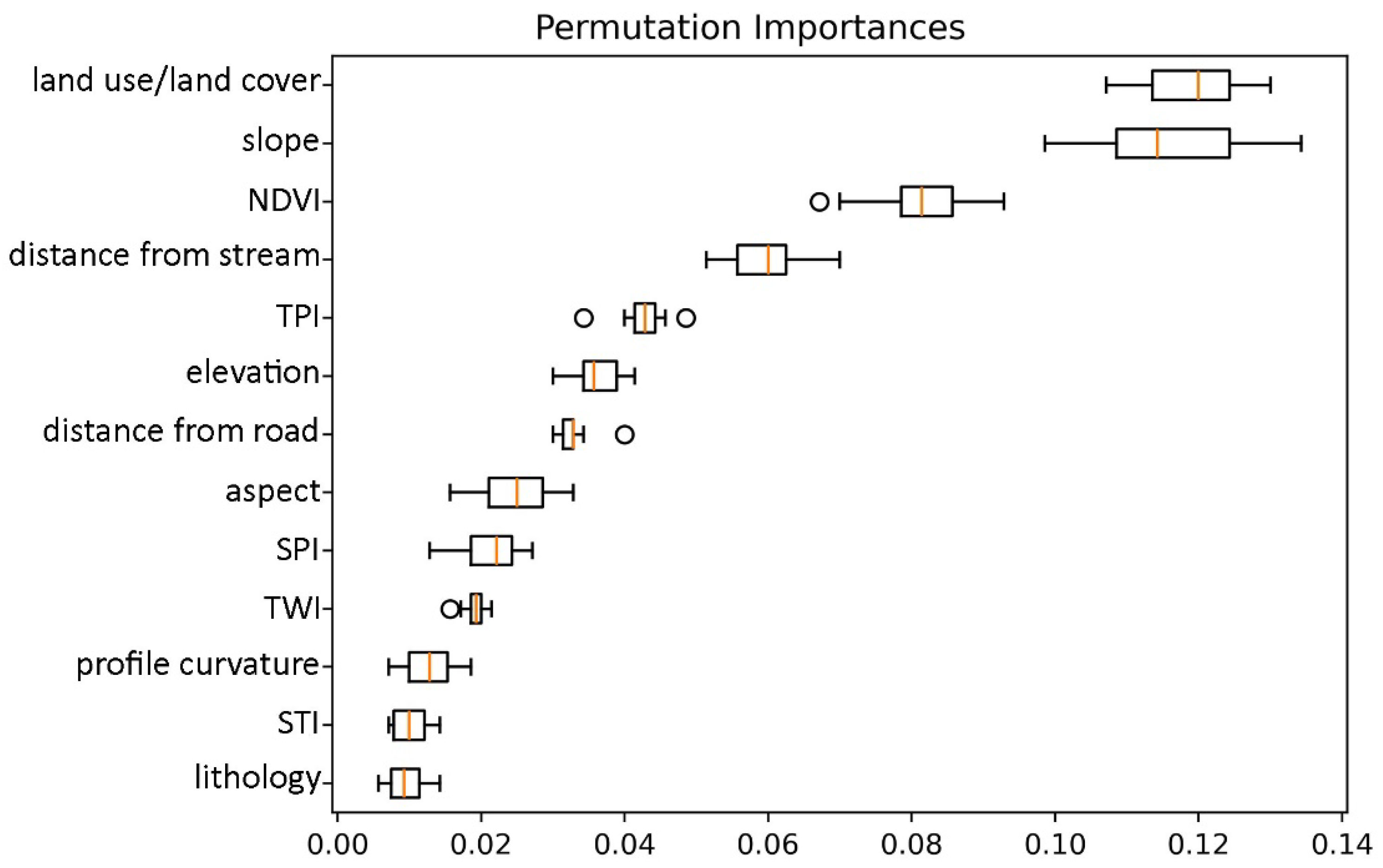

4.5. Importance Assessment of the Factors

5. Discussion

5.1. Assessment of Multicollinearity Among the Geo-Environmental Factors

5.2. Performance of the Machine Learning Algorithms

5.3. Mechanistic Interpretation of Model Differences

5.4. Importance of Contributing Factors and Comparative Insights

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alqadhi, S.; Mallick, J.; Talukdar, S.; Alkahtani, M. An Artificial Intelligence-Based Assessment of Soil Erosion Probability Indices and Contributing Factors in the Abha-Khamis Watershed, Saudi Arabia. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1189184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, H.; Jalali, M.; Rezaei, M.; Mohamadifar, A.; Song, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Niu, B.; Omidvar, E.; Kaskaoutis, D.G. An Explainable Integrated Machine Learning Model for Mapping Soil Erosion by Wind and Water in a Catchment with Three Desiccated Lakes. Aeolian Res. 2024, 67–69, 100924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, H.; Lal, R. Principles of Soil Conservation and Management; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Volume 167169. [Google Scholar]

- Shirani, M.; Afzali, K.N.; Jahan, S.; Strezov, V.; Soleimani-Sardo, M. Pollution and Contamination Assessment of Heavy Metals in the Sediments of Jazmurian Playa in Southeast Iran. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takáts, T.; Pásztor, L.; Árvai, M.; Gáspár, A.; Mészáros, J. Testing the Applicability and Transferability of Data-Driven Geospatial Models for Predicting Soil Erosion in Vineyards. Land 2025, 14, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Westen, C.J.; van Asch, T.W.J.; Soeters, R. Landslide Hazard and Risk Zonation—Why Is It Still So Difficult? Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2006, 65, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quyet Nguyen, C.; Thi Tran, T.; Thanh Thi Nguyen, T.; Ha Thi Nguyen, T.; Astarkhanova, T.S.; Van Vu, L.; Tai Dau, K.; Nguyen, H.N.; Pham, G.H.; Nguyen, D.D.; et al. Mapping of Soil Erosion Susceptibility Using Advanced Machine Learning Models at Nghe An, Vietnam. J. Hydroinformatics 2023, 26, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooshin Nokhandan, F.; Ghahraman, K.; Horváth, E. Erosion Susceptibility Mapping of a Loess-Covered Region Using Analytic Hierarchy Process—A Case Study: Kalat-e-Naderi, Northeast Iran. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2024, 72, 339–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, N.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, C. Response of Soil Detachment Rate to Sediment Load and Model Examination: A Key Process Simulation of Rill Erosion on Steep Loessial Hillslopes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Hou, X.; Li, H. An Improved Minimum Cumulative Resistance Model for Risk Assessment of Agricultural Non-Point Source Pollution in the Coastal Zone. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 312, 120036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echogdali, F.Z.; Boutaleb, S.; Taia, S.; Ouchchen, M.; Id-Belqas, M.; Kpan, R.B.; Abioui, M.; Aswathi, J.; Sajinkumar, K.S. Assessment of Soil Erosion Risk in a Semi-Arid Climate Watershed Using SWAT Model: Case of Tata Basin, South-East of Morocco. Appl. Water Sci. 2022, 12, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksova, B.; Lukić, T.; Milevski, I.; Spalević, V.; Marković, S.B. Modelling Water Erosion and Mass Movements (Wet) by Using GIS-Based Multi-Hazard Susceptibility Assessment Approaches: A Case Study—Kratovska Reka Catchment (North Macedonia). Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micić Ponjiger, T.; Lukić, T.; Wilby, R.L.; Marković, S.B.; Valjarević, A.; Dragićević, S.; Gavrilov, M.B.; Ponjiger, I.; Durlević, U.; Milanović, M.M.; et al. Evaluation of Rainfall Erosivity in the Western Balkans by Mapping and Clustering ERA5 Reanalysis Data. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, R.; Mondal, I.; Dehbozorgi, M.; Bank, S.P.; Das, D.N.; Bandyopadhyay, J.; Pham, Q.B.; Fadhil Al-Quraishi, A.M.; Nguyen, X.C. Modelling and Mapping of Soil Erosion Susceptibility Using Machine Learning in a Tropical Hot Sub-Humid Environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 364, 132428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, H.; Mohammadifar, A. Novel Deep Learning Hybrid Models (CNN-GRU and DLDL-RF) for the Susceptibility Classification of Dust Sources in the Middle East: A Global Source. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lana, J.C.; Castro, P.d.T.A.; Lana, C.E. Assessing Gully Erosion Susceptibility and Its Conditioning Factors in Southeastern Brazil Using Machine Learning Algorithms and Bivariate Statistical Methods: A Regional Approach. Geomorphology 2022, 402, 108159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Fan, H.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, R.; Song, S. Gully Erosion Susceptibility Assessment Based on Machine Learning-A Case Study of Watersheds in Tuquan County in the Black Soil Region of Northeast China. CATENA 2023, 222, 106798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, R.K.; Das Chatterjee, N.; Das, K. Modelling of Soil Erosion Susceptibility Incorporating Sediment Connectivity and Export at Landscape Scale Using Integrated Machine Learning, InVEST-SDR and Fragstats. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 353, 120164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bammou, Y.; Benzougagh, B.; Abdessalam, O.; Brahim, I.; Kader, S.; Spalevic, V.; Sestras, P.; Ercişli, S. Machine Learning Models for Gully Erosion Susceptibility Assessment in the Tensift Catchment, Haouz Plain, Morocco for Sustainable Development. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2024, 213, 105229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahraman, K.; Nagy, B.; Nooshin Nokhandan, F. Flood-Prone Zones of Meandering Rivers: Machine Learning Approach and Considering the Role of Morphology (Kashkan River, Western Iran). Geosciences 2023, 13, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, H.; Mohamadifar, A.; Sorooshian, A.; Jansen, J.D. Machine-Learning Algorithms for Predicting Land Susceptibility to Dust Emissions: The Case of the Jazmurian Basin, Iran. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2020, 11, 1303–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T. Explanation in Artificial Intelligence: Insights from the Social Sciences. Artif. Intell. 2019, 267, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, F.; Shi, X.; Zeng, C.; Maerker, M. Understanding the Mechanism of Gully Erosion in the Alpine Region through an Interpretable Machine Learning Approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 949, 174949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 4765–4774. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, Y.; Shin, J.; Go, B.; Lee, D.-S.; Kim, Y.; Kim, T.; Park, Y.-S. An Interpretable Machine Learning Method for Supporting Ecosystem Management: Application to Species Distribution Models of Freshwater Macroinvertebrates. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 291, 112719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Qiao, J.; Yu, G.; Wang, L.; Li, H.-Y.; Liao, C.; Zhu, Z. Interpretable Tree-Based Ensemble Model for Predicting Beach Water Quality. Water Res. 2022, 211, 118078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadifar, A.; Gholami, H.; Comino, J.R.; Collins, A.L. Assessment of the Interpretability of Data Mining for the Spatial Modelling of Water Erosion Using Game Theory. CATENA 2021, 200, 105178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Chintalacheruvu, M.R. Google Earth Engine-Based Morphometric Parameter Evaluation and Comparative Analysis of Soil Erosion Susceptibility Using Statistical and Machine Learning Algorithms in Large River Basins. Earth Sci. Inform. 2024, 17, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, W.W.; McGarry, D. Organic Carbon and Soil Porosity. Soil Res. 2003, 41, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richthofen, F. Reisen Im Nördlichen China: Ueber Den Chinesischen Löss. Verhandlungen Kais.-K. Geol. Reichsanst. 1872, 8, 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Ruszkiczay-Rüdiger, Z.; Fodor, L.; Horváth, E.; Telbisz, T. Discrimination of Fluvial, Eolian and Neotectonic Features in a Low Hilly Landscape: A DEM-Based Morphotectonic Analysis in the Central Pannonian Basin, Hungary. Geomorphology 2009, 104, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pécsi, M. Loess Is Not Just the Accumulation of Dust. Quat. Int. 1990, 7–8, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Jia, C.; Chen, S.; Li, H. SBAS-InSAR Based Deformation Detection of Urban Land, Created from Mega-Scale Mountain Excavating and Valley Filling in the Loess Plateau: The Case Study of Yan’an City. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köppen, W. Versuch Einer Klassifikation Der Klimate, Vorzugsweise Nach Ihren Beziehungen Zur Pflanzenwelt. (Schluss). Geogr. Z. 1900, 6, 657–679. [Google Scholar]

- Hungarian Meteorological Service. Available online: https://www.met.hu (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Li, H.; Jin, J.; Dong, F.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y. Gully Erosion Susceptibility Prediction Using High-Resolution Data: Evaluation, Comparison, and Improvement of Multiple Machine Learning Models. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oraegbu, A.; Jolaiya, E. Mapping Soil Erosion Classes Using Remote Sensing Data and Ensemble Models. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, XLVIII-4/W12-2024, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Tang, B.; Wang, K.; Shi, J.; Li, M. Evaluation of the Gully Erosion Susceptibility by Using UAV and Hybrid Models Based on Machine Learning. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 244, 106218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.P.C. Soil Erosion and Conservation; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; ISBN 1-4051-4467-X. [Google Scholar]

- Hengl, T. Finding the Right Pixel Size. Comput. Geosci. 2006, 32, 1283–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kienzle, S. The Effect of DEM Raster Resolution on First Order, Second Order and Compound Terrain Derivatives. Trans. GIS 2004, 8, 83–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinzi, K.; Szabó, S. Predictive Machine Learning for Gully Susceptibility Modeling with Geo-Environmental Covariates: Main Drivers, Model Performance, and Computational Efficiency. Nat. Hazards 2024, 120, 7211–7244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Were, K.; Kebeney, S.; Churu, H.; Mutio, J.M.; Njoroge, R.; Mugaa, D.; Alkamoi, B.; Ng’etich, W.; Singh, B.R. Spatial Prediction and Mapping of Gully Erosion Susceptibility Using Machine Learning Techniques in a Degraded Semi-Arid Region of Kenya. Land 2023, 12, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setargie, T.A.; Tsunekawa, A.; Haregeweyn, N.; Tsubo, M.; Fenta, A.A.; Berihun, M.L.; Sultan, D.; Yibeltal, M.; Ebabu, K.; Nzioki, B.; et al. Random Forest–Based Gully Erosion Susceptibility Assessment across Different Agro-Ecologies of the Upper Blue Nile Basin, Ethiopia. Geomorphology 2023, 431, 108671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.-Y. Lightgbm: A Highly Efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Li, L.; Zhao, D. Corporate Finance Risk Prediction Based on LightGBM. Inf. Sci. 2022, 602, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garosi, Y.; Sheklabadi, M.; Conoscenti, C.; Pourghasemi, H.R.; Van Oost, K. Assessing the Performance of GIS- Based Machine Learning Models with Different Accuracy Measures for Determining Susceptibility to Gully Erosion. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 664, 1117–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater Reliability: The Kappa Statistic. Biochem. Medica 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabihi, M.; Mirchooli, F.; Motevalli, A.; Khaledi Darvishan, A.; Pourghasemi, H.R.; Zakeri, M.A.; Sadighi, F. Spatial Modelling of Gully Erosion in Mazandaran Province, Northern Iran. CATENA 2018, 161, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, D.W., Jr.; Lemeshow, S.; Sturdivant, R.X. Applied Logistic Regression; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; ISBN 1-118-54835-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.G.; Lee, S.-I. Consistent Individualized Feature Attribution for Tree Ensembles. arXiv 2018, arXiv:180203888. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, X.; Chen, W.; Avand, M.; Janizadeh, S.; Kariminejad, N.; Shahabi, H.; Costache, R.; Shahabi, H.; Shirzadi, A.; Mosavi, A. GIS-Based Machine Learning Algorithms for Gully Erosion Susceptibility Mapping in a Semi-Arid Region of Iran. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, M.; Ghosh, A.; Zafor, M.A.; Maiti, R. Evaluating the Integrated Performance and Effectiveness of RUSLE through Machine Learning Algorithm on Soil Erosion Susceptibility in Tropical Plateau Basin, India. J. Sediment. Environ. 2024, 9, 665–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, K.; Rezaie, F.; Cooper, J.R.; Kalantari, Z.; Abolfathi, S.; Hatamiafkoueieh, J. Soil Water Erosion Susceptibility Assessment Using Deep Learning Algorithms. J. Hydrol. 2023, 618, 129229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Su, L.; Fan, H.; Zhou, L.; Tian, Y. Identification of Topographic Factors for Gully Erosion Susceptibility and Their Spatial Modelling Using Machine Learning in the Black Soil Region of Northeast China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 143, 109376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Chen, L.; Zhang, H.; Yang, L.; Yu, Y.; Chen, J. Effects of Crop Rotation and Rainfall on Water Erosion on a Gentle Slope in the Hilly Loess Area, China. CATENA 2014, 123, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gábris, G.; Kertész, Á.; Zámbó, L. Land Use Change and Gully Formation over the Last 200 Years in a Hilly Catchment. CATENA 2003, 50, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manekar, U.; Sharma, S.K.; Trivedi, S.K.; Meena, H. Effect of Tillage Management and Soil Slope on Annual Soil Loss Under Cereal Crops in Central India. 2023. Available online: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/gim/resource/enauMartinsNetoViviana/sea-229965 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

| Geo-Environmental Factor | Input Source | Unit/Data Type | Physical Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elevation | ALOS PALSAR DEM/12.5 m | 171–283 m/Continuous | Controls potential energy & microclimate |

| Slope | Derived from DEM/12.5 m | 0–29.22 degrees/Continuous | Governs runoff velocity & shear stress |

| Aspect | Derived from DEM/12.5 m | 0–365 degrees/Continuous | Influences solar radiation & soil moisture |

| Profile Curvature | Derived from DEM/12.5 m | −2.56–2.94/Continuous | Affects flow convergence/divergence |

| Topographic position index (TPI) | Derived from DEM/12.5 m | −25.09–26.36/Continuous | Indicates landscape position (ridge/valley) |

| Topographic wetness index (TWI) | Derived from DEM/12.5 m | 3.26–21.46/Continuous | Represents potential water accumulation |

| Stream power index (SPI) | Derived from DEM/12.5 m | −13.81–9.20/Continuous | Indicates erosive power of concentrated flow |

| Sediment transport index (STI) | Derived from DEM/12.5 m | 0–619.43/Continuous | Represents sediment transport capacity |

| Distance from stream | Derived from DEM/12.5 m | 0 → 400 m/Continuous | Indicates proximity to drainage network base level |

| Lithology | Hungarian Geological Database/1:100,000 | Loess, Rivers sand, Fluvioeolian sand, fluvial siltstone/Categorical | Controls erodibility & permeability |

| Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) | Sentinel-2 Imagery/10 m | −0.2–0.73/Continuous | Quantifies protective vegetation cover |

| Land use/Land cover (LULC) | Pacific Geoportal/10 m | Water, Tree, Crop, Built area, Bare ground, Rangeland/Categorical | Defines surface condition & human disturbance |

| Distance from road | Open Street Map (OSM)/vector | 0 → 800 m/Continuous | Represents potential flow barriers or disturbances |

| Train Dataset | Test Dataset | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | LightGBM | Random Forest | LightGBM | |

| RMSE | 0.18 | 0.26 | 0.38 | 0.39 |

| MAE | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.16 |

| Kappa coefficient | 0.93 | 0.85 | 0.70 | 0.67 |

| Overall Accuracy | 0.94 | 0.9 | 0.81 | 0.82 |

| AUROC | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.90 | 0.91 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nooshin Nokhandan, F.; Ghahraman, K.; Novothny, Á.; Horváth, E. Advancing Soil Erosion Mapping in Active Agricultural Lands Using Machine Learning and SHAP Analysis. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3950. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243950

Nooshin Nokhandan F, Ghahraman K, Novothny Á, Horváth E. Advancing Soil Erosion Mapping in Active Agricultural Lands Using Machine Learning and SHAP Analysis. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3950. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243950

Chicago/Turabian StyleNooshin Nokhandan, Fatemeh, Kaveh Ghahraman, Ágnes Novothny, and Erzsébet Horváth. 2025. "Advancing Soil Erosion Mapping in Active Agricultural Lands Using Machine Learning and SHAP Analysis" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3950. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243950

APA StyleNooshin Nokhandan, F., Ghahraman, K., Novothny, Á., & Horváth, E. (2025). Advancing Soil Erosion Mapping in Active Agricultural Lands Using Machine Learning and SHAP Analysis. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3950. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243950