Advancing Hyperspectral LWIR Imaging of Soils with a Controlled Laboratory Setup

Highlights

- Imaging laboratory spectroscopy in the longwave infrared (LWIR) range allows reliable and repeatable measurements of soil emissivity.

- Tests on different soils showed that the LWIR laboratory results agree well with outdoor measurements and mineral analyses.

- Our approach provides a weather-independent way to measure soils in the LWIR range and semi-quantify their minerology.

- It establishes a solid basis for calibrating satellite and airborne LWIR data, improving soil and environmental monitoring with the potential of becoming a standard protocol for these types of campaigns.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

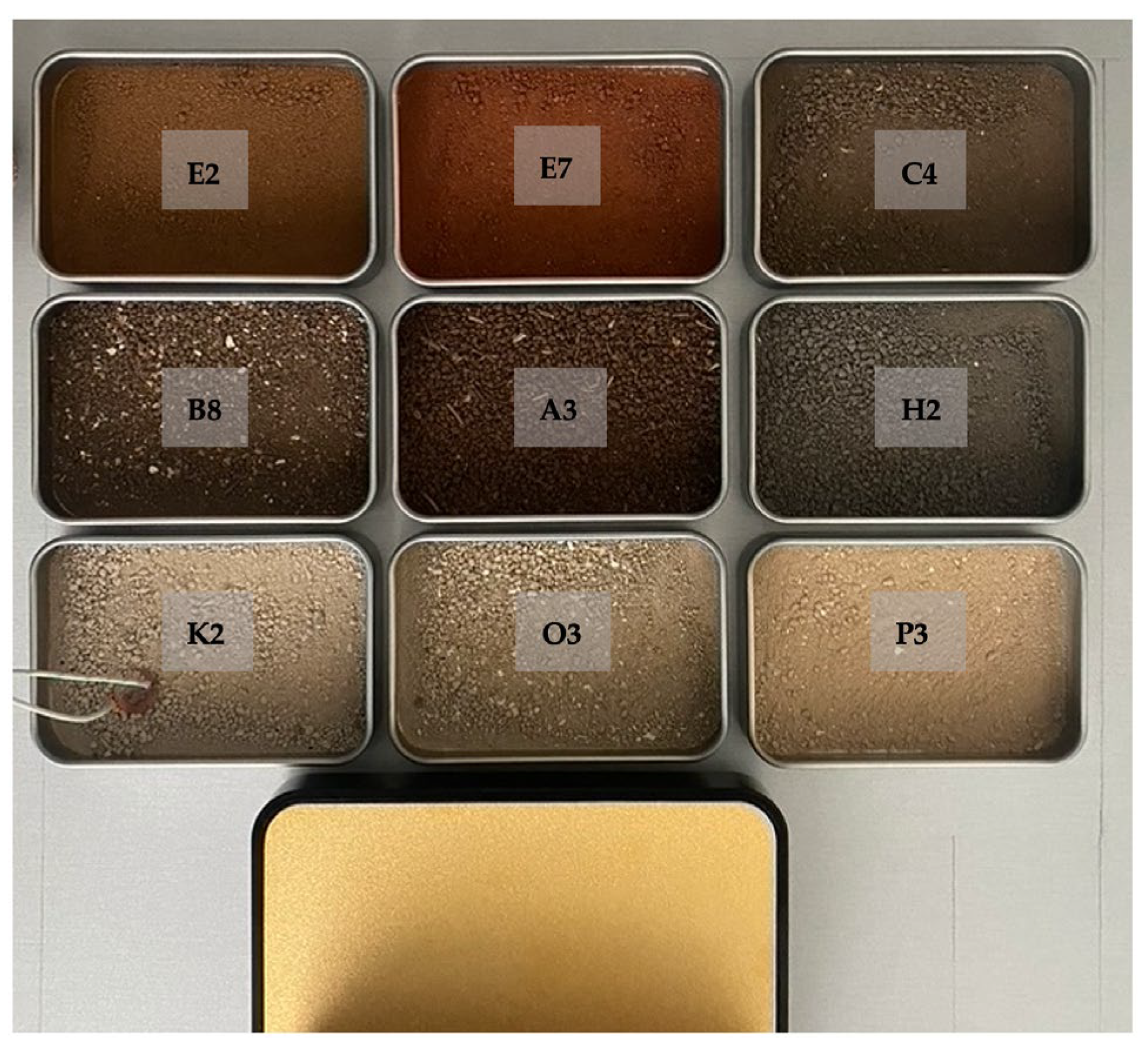

2.1. Soil Samples and Mineral Abundance

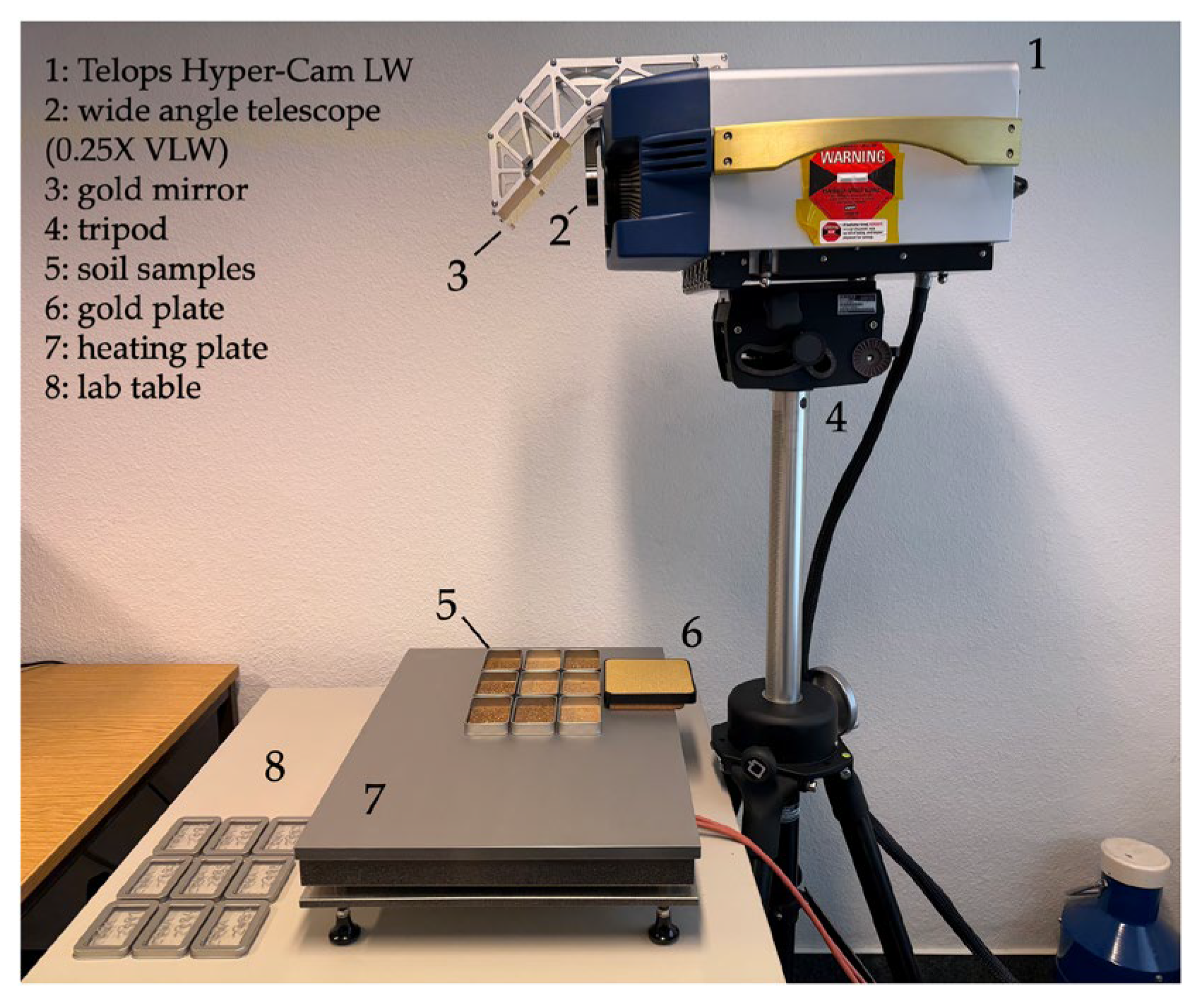

2.2. Laboratory Setup

2.3. Data Pre-Processing

2.3.1. Laboratory TES Using a Blackbody Fitting Approach

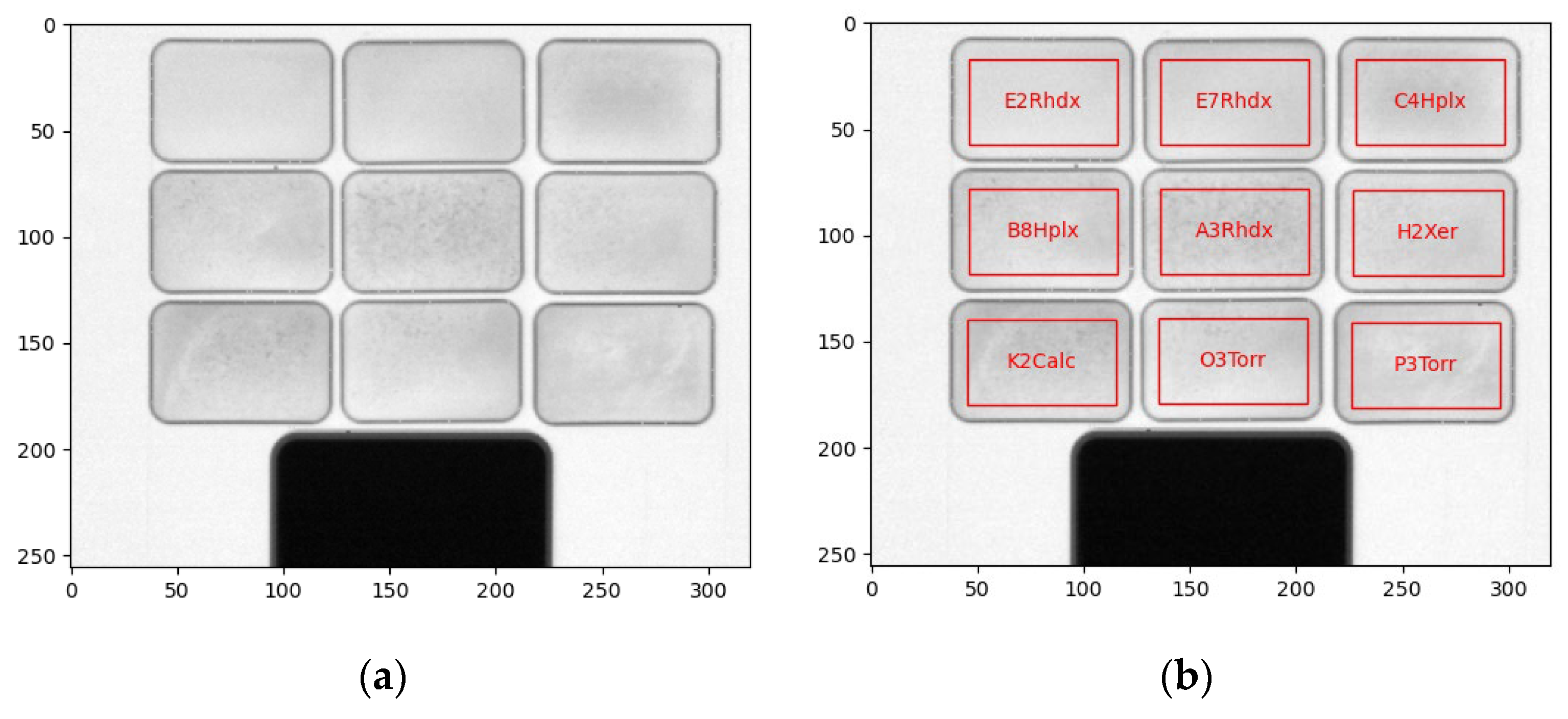

2.3.2. Automated ROI Extraction

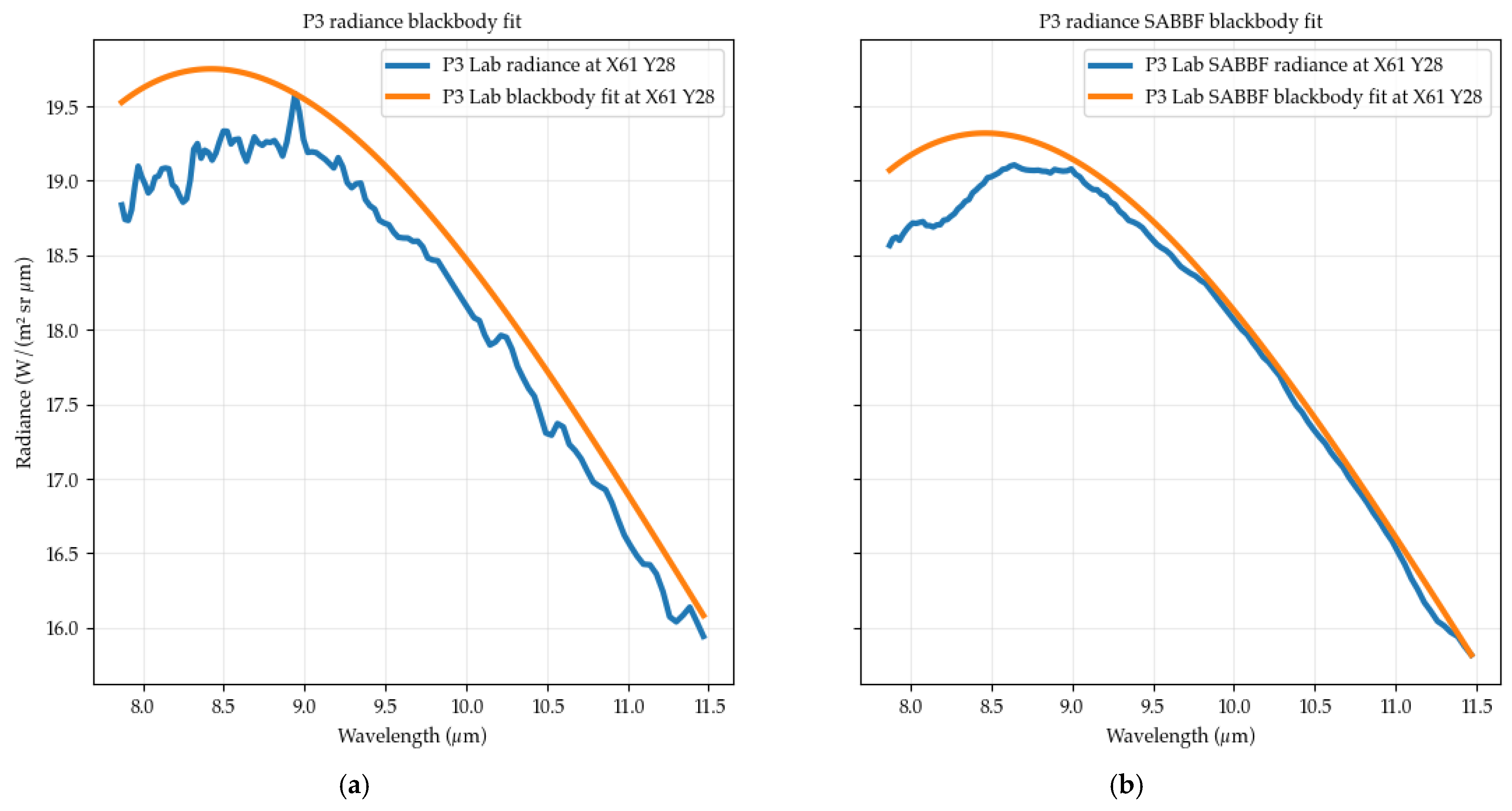

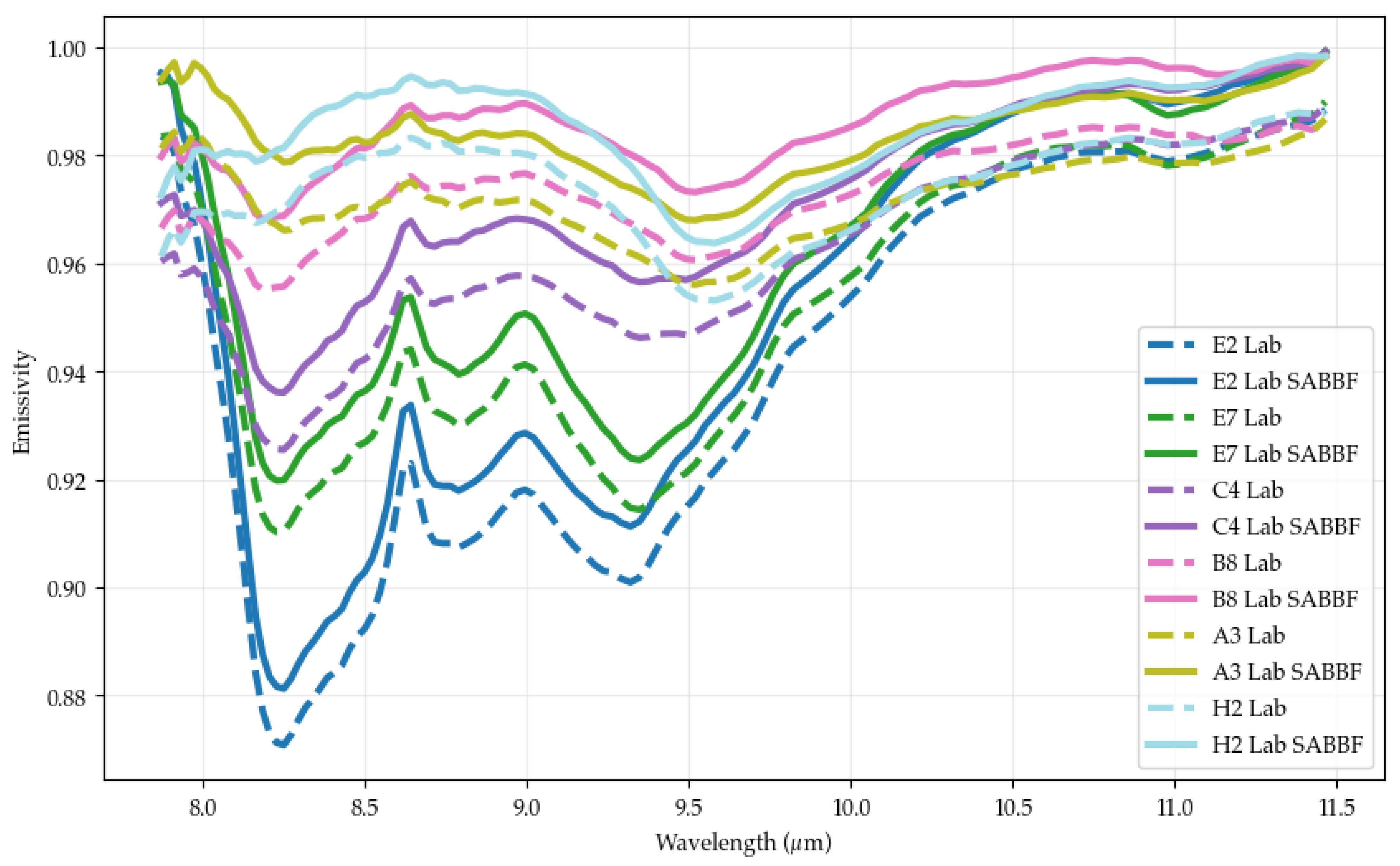

2.3.3. Spatial Averaging Before Blackbody Fitting (SABBF)

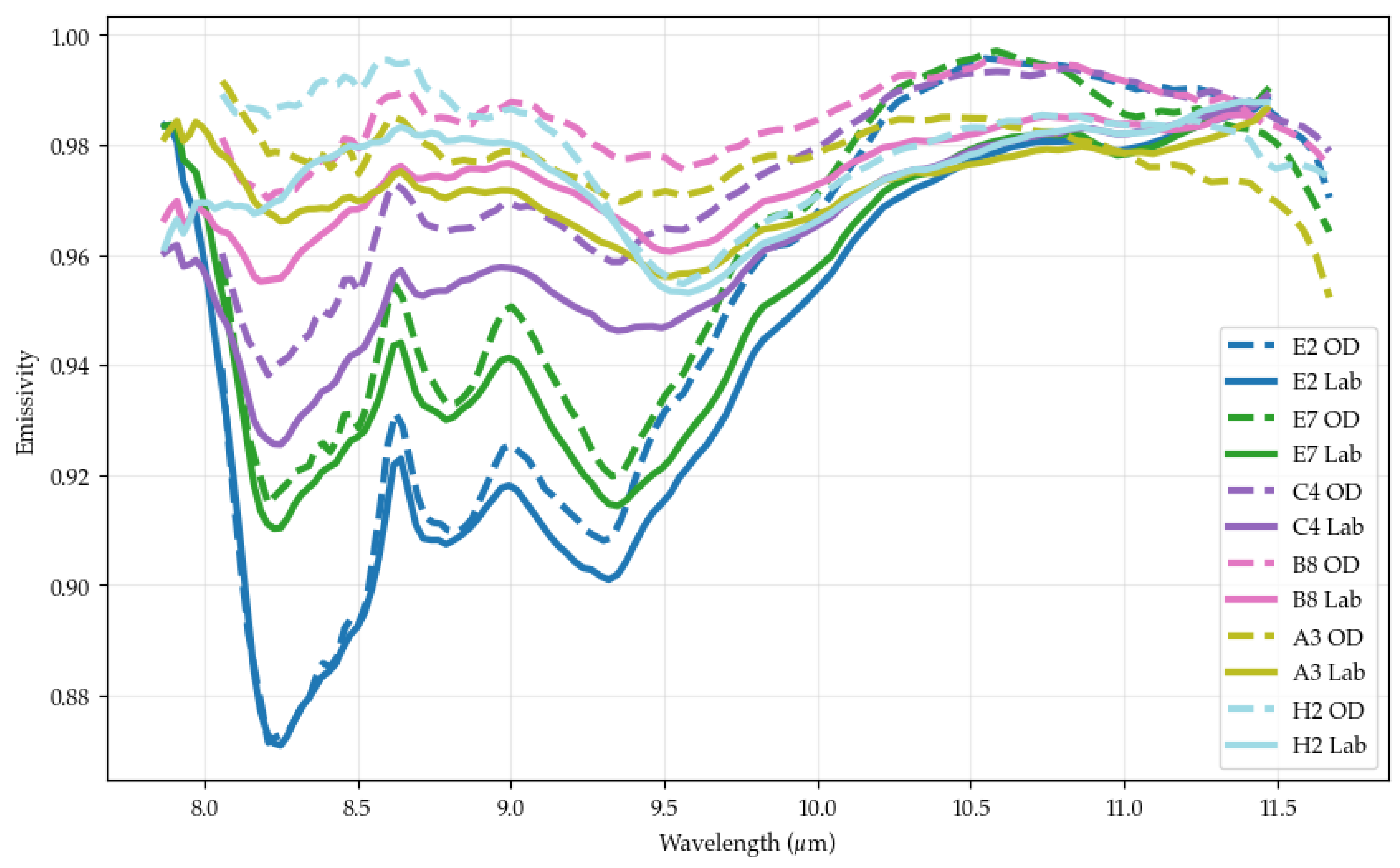

2.4. Validation with Outdoor Lab Measurements

2.5. Mineralogical Identification

2.6. Statisical Analysis

3. Results

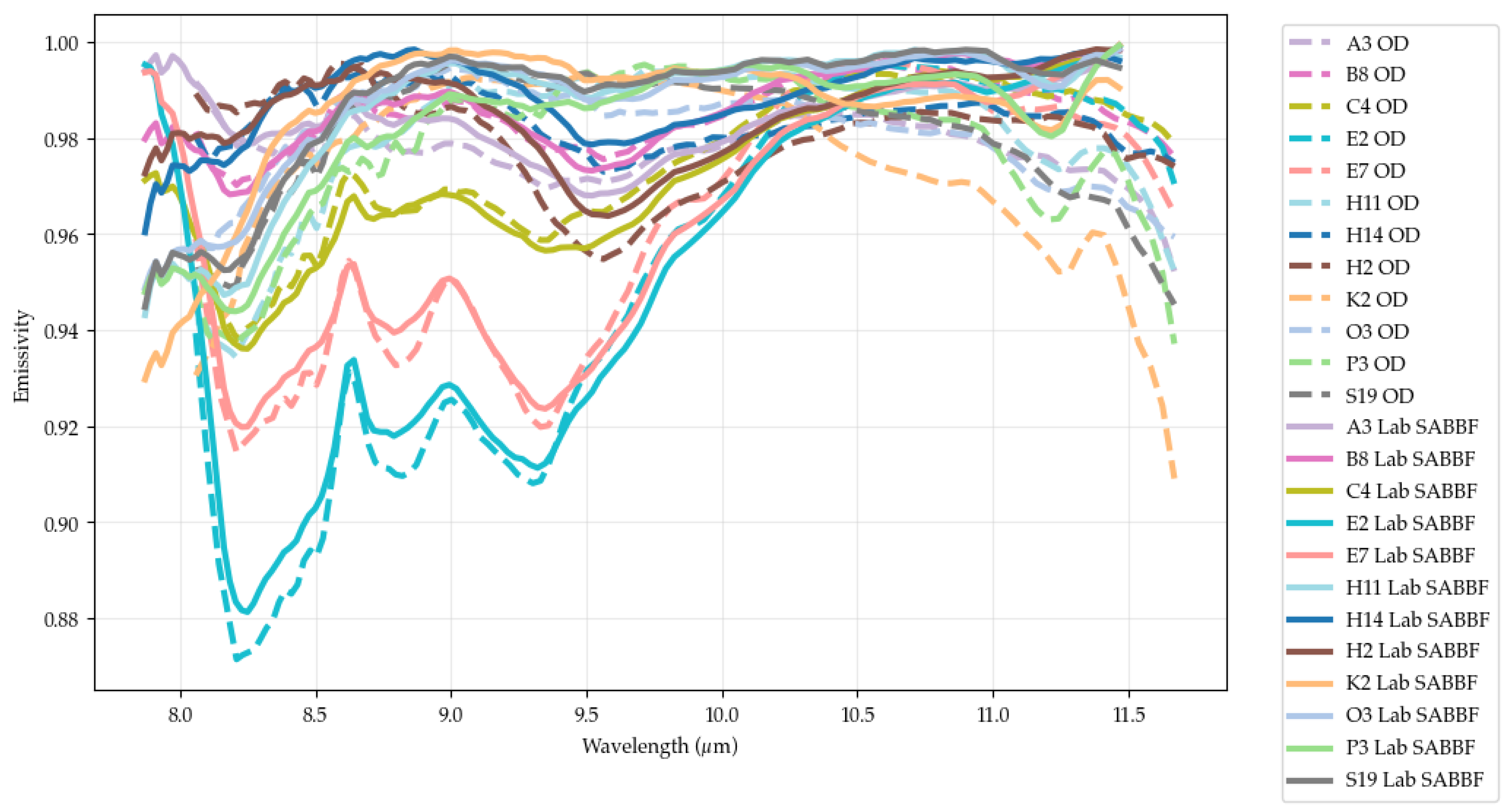

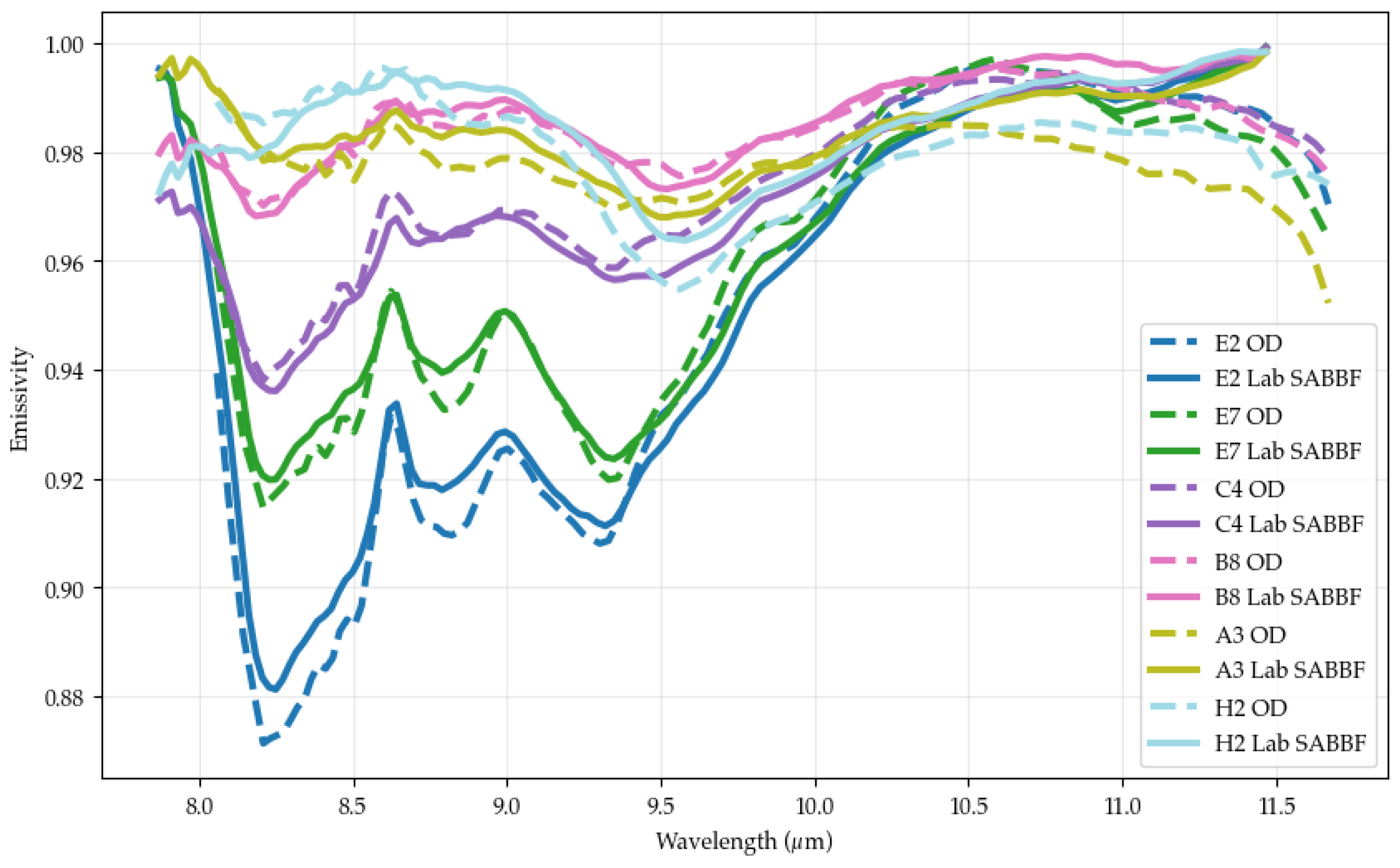

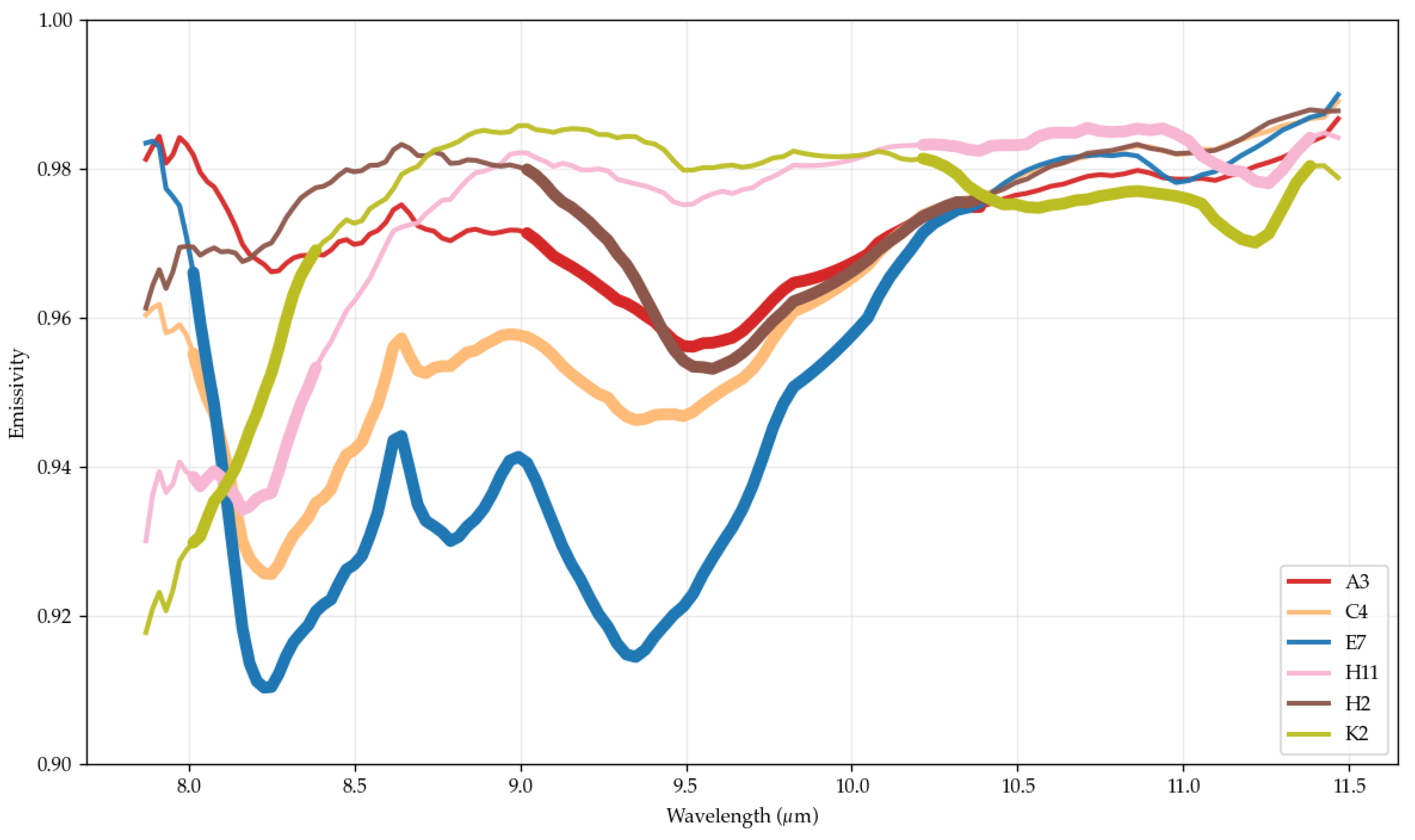

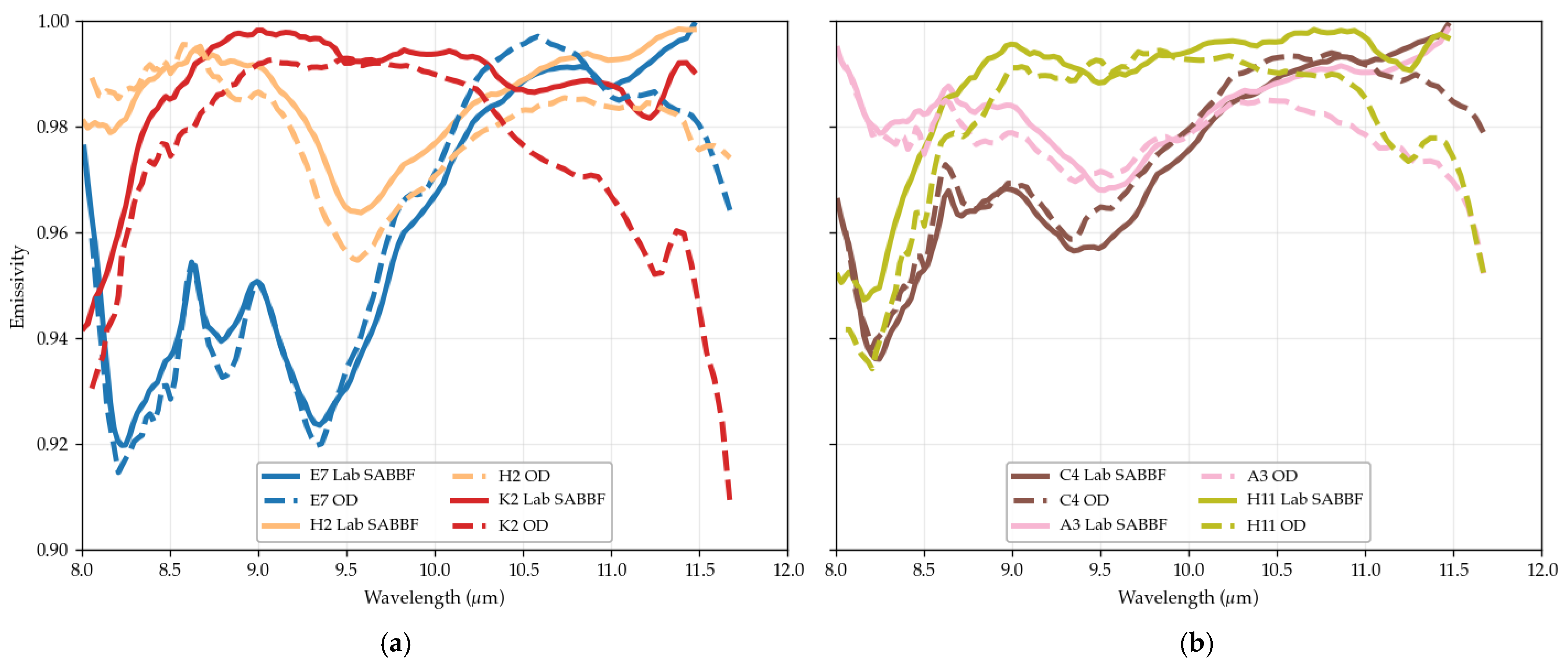

3.1. Emissivity Spectra

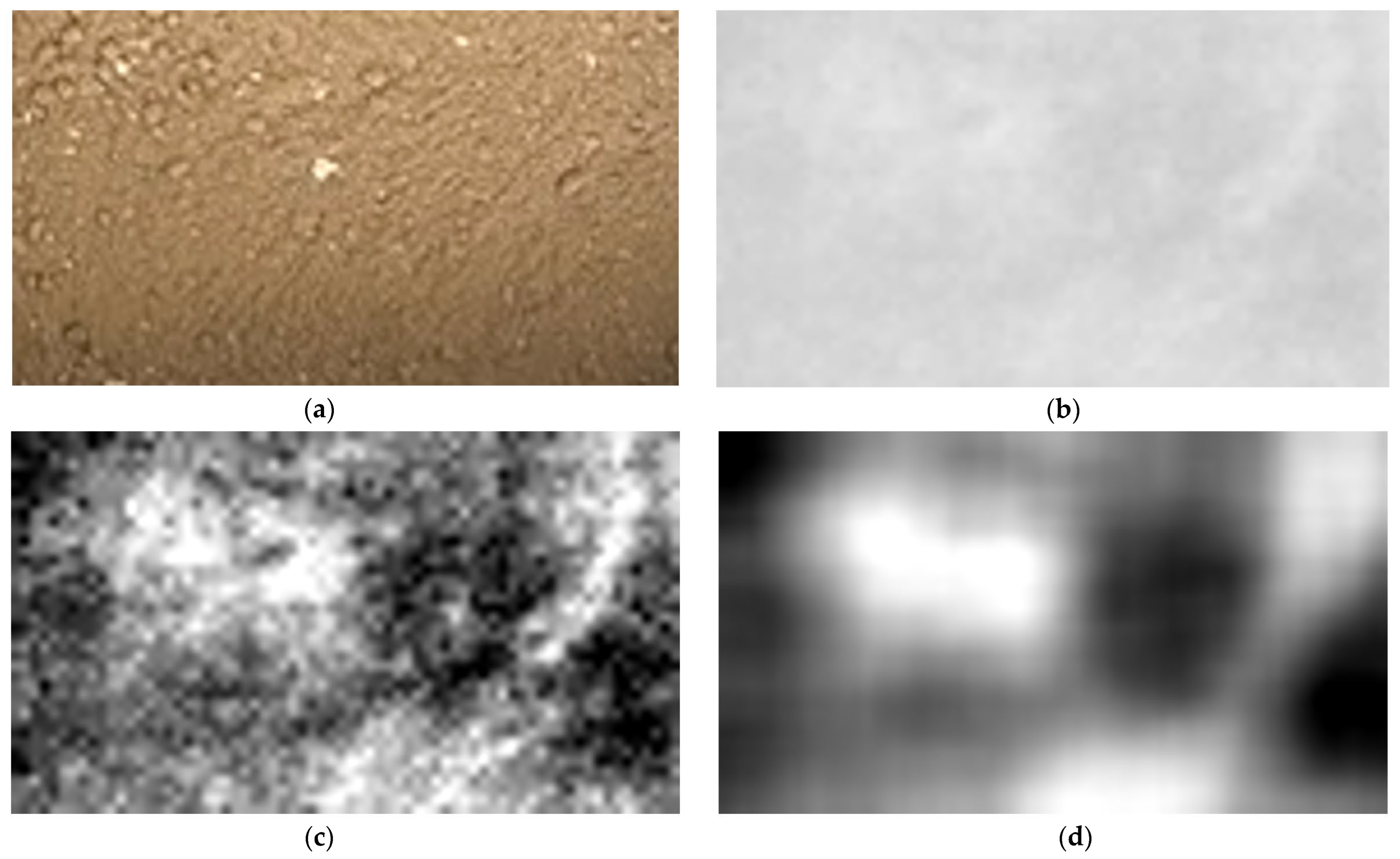

3.2. Impact of Spatial Averaging Before Blackbody Fitting (SABBF)

3.3. Mineralogical Identification and Semi-Quantification

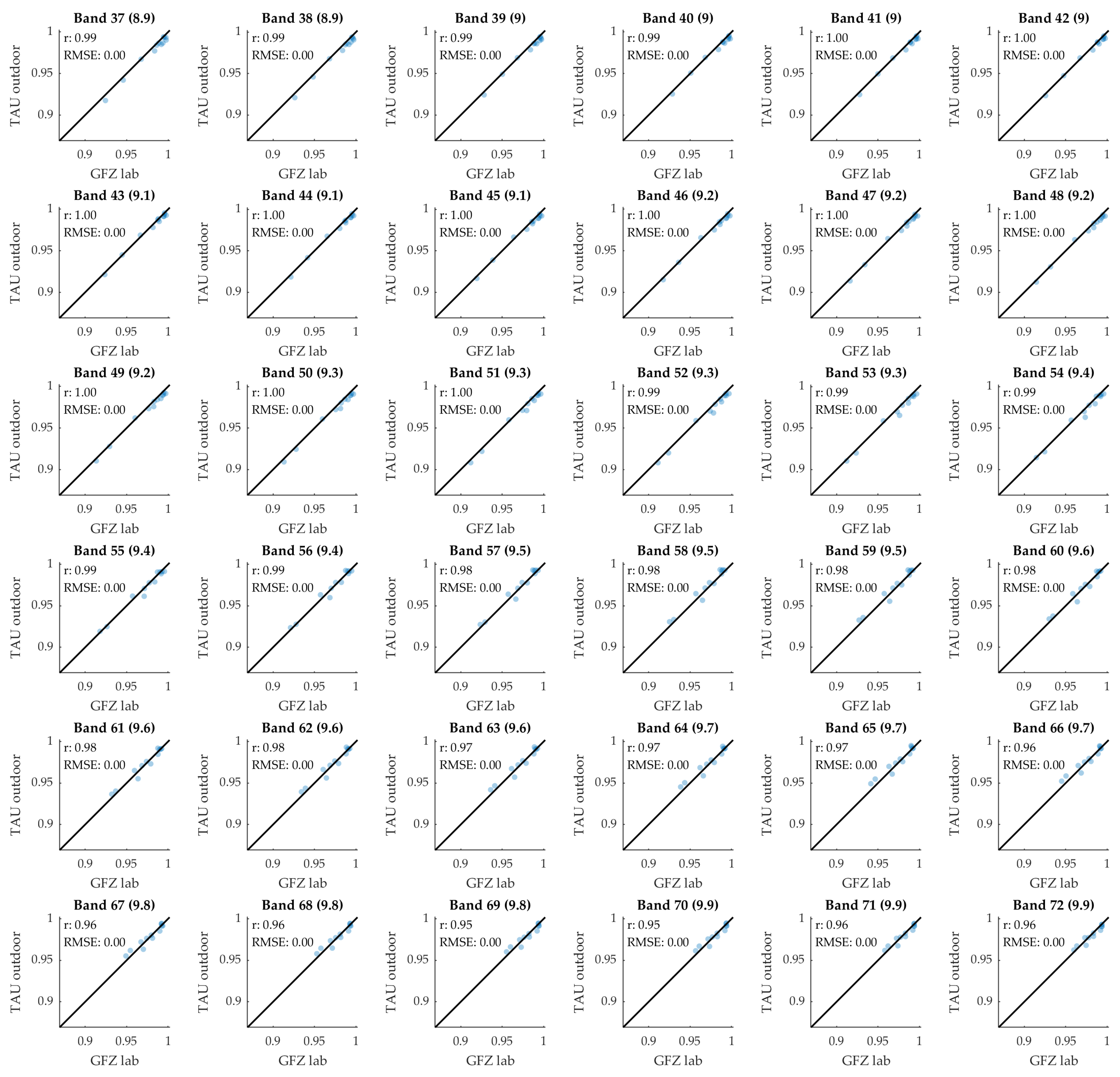

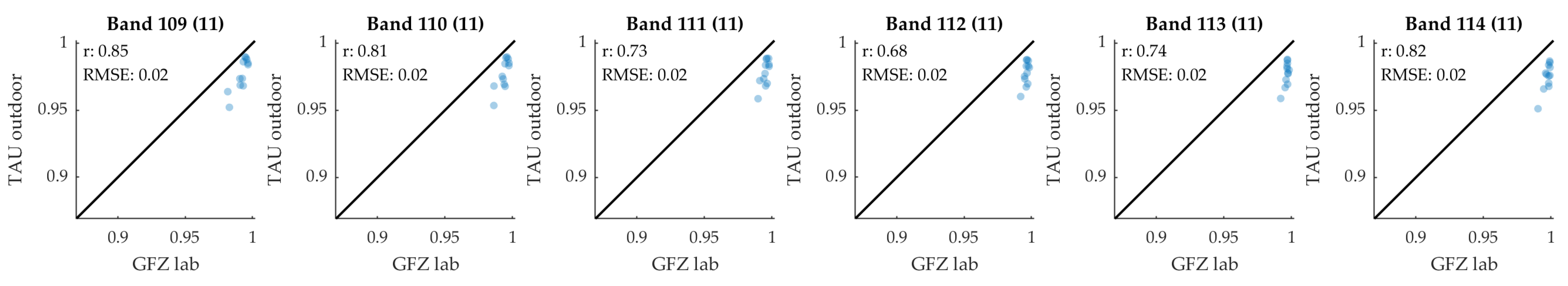

3.4. Statistical Agreement Between SABBF and Outdoor Measurements

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LWIR | Longwave infrared |

| XRD | X-ray powder diffraction |

| MCT | Mercury-cadmium-telluride |

| DFT | Discrete-Fourier transform |

| FOV | Field of view |

| RGB | Red, green, blue (e.g., standard color bands of a (true) color image) |

| ROI | Region of Interest |

| TES | Temperature Emissivity separation |

| SNR | Signal-to-noise ratio |

| SABBF | Spatial Averaging Before Blackbody Fitting |

| BB | Blackbody |

| IDL | Interactive Data Language |

Appendix A

References

- Chabrillat, S.; Ben-Dor, E.; Cierniewski, J.; Gomez, C.; Schmid, T.; Van Wesemael, B. Imaging Spectroscopy for Soil Mapping and Monitoring. Surv. Geophys. 2019, 40, 361–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Dor, E.; Chabrillat, S.; Demattê, J.A.M.; Taylor, G.R.; Hill, J.; Whiting, M.L.; Sommer, S. Using Imaging Spectroscopy to Study Soil Properties. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113, S38–S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabrillat, S.; Ben-Dor, E.; Rossel, R.A.V.; Demattê, J.A.M. Quantitative Soil Spectroscopy. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2013, 2013, 616578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notesco, G.; Weksler, S.; Ben-Dor, E. Mineral Classification of Soils Using Hyperspectral Longwave Infrared (LWIR) Ground-Based Data. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milewski, R.; Abdelbaki, A.; Chabrillat, S.; Tziolas, N.; Van Wesemael, B.; Jacquemoud, S. Simulation of Spectral Disturbance Effects for Improvement of Soil Property Estimation. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2023—2023 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Pasadena, CA, USA, 16–21 July 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1257–1260. [Google Scholar]

- Milewski, R.; Schmid, T.; Chabrillat, S. LAI Modeling in Degraded Mediterranean Rainfed Cultivated Crop Linked with Soil Erosion Stages Based on VNIR-SWIR Hyperspectral Data. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium IGARSS, Brussels, Belgium, 11–16 July 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 5865–5868. [Google Scholar]

- Soriano-Disla, J.M.; Janik, L.J.; Viscarra Rossel, R.A.; Macdonald, L.M.; McLaughlin, M.J. The Performance of Visible, Near-, and Mid-Infrared Reflectance Spectroscopy for Prediction of Soil Physical, Chemical, and Biological Properties. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2014, 49, 139–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisele, A.; Lau, I.; Hewson, R.; Carter, D.; Wheaton, B.; Ong, C.; Cudahy, T.J.; Chabrillat, S.; Kaufmann, H. Applicability of the Thermal Infrared Spectral Region for the Prediction of Soil Properties Across Semi-Arid Agricultural Landscapes. Remote Sens. 2012, 4, 3265–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisele, A.; Chabrillat, S.; Hecker, C.; Hewson, R.; Lau, I.C.; Rogass, C.; Segl, K.; Cudahy, T.J.; Udelhoven, T.; Hostert, P.; et al. Advantages Using the Thermal Infrared (TIR) to Detect and Quantify Semi-Arid Soil Properties. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 163, 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopačková, V.; Ben-Dor, E.; Carmon, N.; Notesco, G. Modelling Diverse Soil Attributes with Visible to Longwave Infrared Spectroscopy Using PLSR Employed by an Automatic Modelling Engine. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutengs, C.; Ludwig, B.; Jung, A.; Eisele, A.; Vohland, M. Comparison of Portable and Bench-Top Spectrometers for Mid-Infrared Diffuse Reflectance Measurements of Soils. Sensors 2018, 18, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertin, E.P. Qualitative and Semiquantitative Analysis. In Introduction to X-Ray Spectrometric Analysis; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1978; pp. 255–278. ISBN 978-0-306-31091-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Dor, E.; Banin, A. Visible and Near-Infrared (0.4–1.1 Μm) Analysis of Arid and Semiarid Soils. Remote Sens. Environ. 1994, 48, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, P.; Biswas, A.K.; Lakaria, B.L.; Saha, R.; Singh, M.; Rao, A.S. Predicting Total Organic Carbon Content of Soils from Walkley and Black Analysis. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2014, 45, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schodlok, M.C.; Frei, M. LWIR Hyperspectral Mapping of the Gamsberg Deposit, Aggeneys, South Africa. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2020—2020 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 26 September–2 October 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 5135–5138. [Google Scholar]

- Schlerf, M.; Rock, G.; Lagueux, P.; Ronellenfitsch, F.; Gerhards, M.; Hoffmann, L.; Udelhoven, T. A Hyperspectral Thermal Infrared Imaging Instrument for Natural Resources Applications. Remote Sens. 2012, 4, 3995–4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagueux, P.; Farley, V.; Rolland, M.; Chamberland, M.; Puckrin, E.; Turcotte, C.S.; Lahaie, P.; Dube, D. Airborne Measurements in the Infrared Using FTIR-Based Imaging Hyperspectral Sensors. In Proceedings of the 2009 First Workshop on Hyperspectral Image and Signal Processing: Evolution in Remote Sensing, Grenoble, France, 26–28 August 2009; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- De Ridder, K.; Gallée, H. Land Surface–Induced Regional Climate Change in Southern Israel. J. Appl. Meteor. 1998, 37, 1470–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Materia, S.; Ardilouze, C.; Prodhomme, C.; Donat, M.G.; Benassi, M.; Doblas-Reyes, F.J.; Peano, D.; Caron, L.-P.; Ruggieri, P.; Gualdi, S. Summer Temperature Response to Extreme Soil Water Conditions in the Mediterranean Transitional Climate Regime. Clim. Dyn. 2022, 58, 1943–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminzadeh, M.; Or, D.; Stevens, B.; AghaKouchak, A.; Shokri, N. Upper Bounds of Maximum Land Surface Temperatures in a Warming Climate and Limits to Plant Growth. Earths Future 2023, 11, e2023EF003755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascucci, S.; Casa, R.; Belviso, C.; Palombo, A.; Pignatti, S.; Castaldi, F. Estimation of Soil Organic Carbon from Airborne Hyperspectral Thermal Infrared Data: A Case Study. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2014, 65, 865–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, J.-P.; Chamberland, M.; Farley, V.; Marcotte, F.; Rolland, M.; Vallières, A.; Villemaire, A. Airborne Measurements in the Longwave Infrared Using an Imaging Hyperspectral Sensor; McLean, I.S., Casali, M.M., Eds.; Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers (SPIE): Marseille, France, 2008; p. 70143Q. [Google Scholar]

- Hecker, C.A.; Smith, T.E.L.; Da Luz, B.R.; Wooster, M.J. Thermal Infrared Spectroscopy in the Laboratory and Field in Support of Land Surface Remote Sensing. In Thermal Infrared Remote Sensing; Kuenzer, C., Dech, S., Eds.; Remote Sensing and Digital Image Processing; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 17, pp. 43–67. ISBN 978-94-007-6638-9. [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, M.J.D. A New Algorithm for Unconstrained Optimization. In Nonlinear Programming; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1970; pp. 31–65. ISBN 978-0-12-597050-1. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, M.J.D. A Hybrid Method for Nonlinear Equations. In Numerical Methods for Nonlinear Algebraic Equations; Gordon and Breach Science: London, UK, 1970; pp. 87–161. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, J.E.; Schnabel, R.B. Numerical Methods for Unconstrained Optimization and Nonlinear Equations: Originally Published: Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, C1983; Classics in applied mathematics; Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-1-61197-120-0. [Google Scholar]

- Notesco, G.; Kopačková, V.; Rojík, P.; Schwartz, G.; Livne, I.; Dor, E. Mineral Classification of Land Surface Using Multispectral LWIR and Hyperspectral SWIR Remote-Sensing Data. A Case Study over the Sokolov Lignite Open-Pit Mines, the Czech Republic. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 7005–7025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradski, G. The OpenCV Library. Dr. Dobbs J. Softw. Tools 2000, 120, 122–125. [Google Scholar]

- Elvidge, C.D. Thermal Infrared Reflectance of Dry Plant Materials: 2.5–20.0 Μm. Remote Sens. Environ. 1988, 26, 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, J.E.; Kanner, O.; Amir, O.; Efrati, B.; Ben-Dor, E. Long-Term Stability of Soil Spectral Libraries with Chemical and Spectral Insights. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil (Symbol, USDA Great Group Name) | Mineral Abundance (%) a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartz | Clay Minerals b | Carbonates c | Organic Carbon d | |

| E2, Rhodoxeralf | 90 | 5 | 0 | 0.17 |

| E7, Rhodoxeralf | 75 | 15 | 1 | 0.16 |

| C4, Haploxeroll | 55 | 30 | 12 | 0.73 |

| B8, Haploxeroll | 30 | 40 | 31 | 1.95 |

| A3, Rhodoxeralf | 35 | 58 | 2 | 2.64 |

| H2, Xerert | 4 | 67 | 21 | 1.85 |

| K2, Calciorthid | 15 | 0 | 60 | 1.27 |

| O3, Torriorthent | 25 | 10 | 59 | 0.30 |

| P3, Torriorthent | 25 | 7 | 68 | 0.19 |

| H11, Haplargid | 36 | 10 | 54 | 0.56 |

| H14, Xerert | 25 | 45 | 28 | 1.22 |

| S19, Torriorthent | 47 | 10 | 43 | 0.77 |

| Sensor | Telops Hyper-Cam LW (FTIR) |

|---|---|

| Spectral Range (μm) | 7.7–11.8 |

| Spectral Resolution (cm−1) | Up to 0.25 |

| Spectral Resolution used (cm−1) | 4 |

| Spatial Resolution | 320 × 256 (Full Frame) |

| FOV (Degrees) | 6.4 × 5.1 |

| Typical NESR (NW/CM2 SR CM−1) | 20 |

| Radiometric Accuracy (K) | <1.0 |

| Calibration | 2 Internal Blackbodies |

| Most Abundant Mineral | Spectral Indicant |

|---|---|

| Clay minerals | Nελ=9.58 µm a < Nελ=8.25 µm and Nελ=8.25 µm > 0.98 |

| Carbonates | ελ=8.00–8.18 µm b < ελ=8.25 µm and/or Nελ=11.22 µm < 0.995 with Nελ=8.25 µm > 0.98 |

| Quartz | Excluding the above |

| Soil Type a | Indicant | Relative Amount of Mineral(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Q | SCI < 1.010 | C > CM |

| 1.010 ≤ SCI < 1.020 and SQCMI > 1.020 | C > CM | |

| SCI > 1.020 SCI > 1.050, SQCMI > 1.200 | CM > C no C, no CM | |

| CM | Absorption at 8.16 µm and/or SCI < 1.005 | C > Q |

| C | SQCMI > 1.010 with Nελ=8.25 µm < 0.990 | Q > CM |

| Soil | Mineralogy (More to Less Abundant) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory-Based | Outdoor-Based | XRD Analysis | |

| E2 | Q CM C | Q CM C | Q CM |

| E7 | Q CM C | Q CM C | Q CM C |

| C4 | Q C CM | Q CM C | Q CM C |

| B8 | CM C Q | CM C Q | CM C Q |

| A3 | CM C Q | CM Q C | CM Q C |

| H2 | CM C Q | CM C Q | CM C Q |

| K2 | C CM Q | C CM Q | C Q |

| O3 | C CM Q | C CM Q | C Q CM |

| P3 | C Q CM | C Q CM | C Q CM |

| H11 | C CM Q | C Q CM | C Q CM |

| H14 | CM C Q | CM C Q | CM C Q |

| S19 | Q C CM | Q C CM | Q C CM |

| n Emissivity Bands | r2 | RMSE [Emissivity %] | MAE [Emissivity %] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1368 | 0.91 | 0.79% | 0.58% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daempfling, H.L.C.; Milewski, R.; Notesco, G.; Ben-Dor, E.; Chabrillat, S. Advancing Hyperspectral LWIR Imaging of Soils with a Controlled Laboratory Setup. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3926. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233926

Daempfling HLC, Milewski R, Notesco G, Ben-Dor E, Chabrillat S. Advancing Hyperspectral LWIR Imaging of Soils with a Controlled Laboratory Setup. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(23):3926. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233926

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaempfling, Helge L. C., Robert Milewski, Gila Notesco, Eyal Ben-Dor, and Sabine Chabrillat. 2025. "Advancing Hyperspectral LWIR Imaging of Soils with a Controlled Laboratory Setup" Remote Sensing 17, no. 23: 3926. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233926

APA StyleDaempfling, H. L. C., Milewski, R., Notesco, G., Ben-Dor, E., & Chabrillat, S. (2025). Advancing Hyperspectral LWIR Imaging of Soils with a Controlled Laboratory Setup. Remote Sensing, 17(23), 3926. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233926