1. Introduction

Forestry plays a critical role in ensuring environmental sustainability and maintaining global ecological balance, serving as a significant reservoir for biodiversity, carbon sequestration, and renewable resources. Forest inventory is one of the key activities in forest management. It serves as the primary source of information for assessing forest structure and monitoring forest dynamics [

1]. A core component of sustainable forest management is the accurate measurement of forest structural attributes, among which is the diameter at breast height (DBH), which is one of the most critical. DBH is extensively used to estimate tree volume, biomass, carbon stock, and overall forest structure. Various methods can be employed to gather information about forests, each relying on the measurement of distinct variables.

In forestry research, it is essential to distinguish between stand-level variables and individual tree variables, as each category offers unique insights into forest dynamics. Stand-level variables, such as basal area, stem density, and canopy cover, provide aggregated information about forest stands, facilitating assessments of overall forest health and productivity. In contrast, individual tree variables, including diameter at breast height (DBH), tree height, and crown dimensions, offer detailed data crucial for understanding growth patterns and resource competition among individual trees. While most of the previous studies focused on trees within a research plot and created images for the whole research area, capturing the trees individually within the forest stand can result in better estimation accuracies [

2]. Several researchers have developed growth and yield models based on an individual tree approach [

3].

DBH is often marked as the most important parameter for the estimation of forest information [

4]. This metric serves as a critical parameter for estimating timber volume, biomass, and overall forest structure [

5]. It is commonly used to measure tree size and growth status within forests [

6]. DBH is also used to calculate important ecological and economic variables, such as tree growth rates, forest stand density, and carbon sequestration potential. Traditionally, DBH has been measured using tools like calipers or diameter tapes. The high labor intensity, high labor cost, error-prone and inefficient manual reading and recording of data throughout the measurement process severely limit the efficiency and quality of the related survey work [

7]. Devices which can obtain DBH in a rapid and accurate manner are highly anticipated [

8]. Given its role in forest management, DBH is also a fundamental factor in determining tree age, health, and suitability for harvest.

Recent advances in proximal sensing technologies—tools used in close range to the target—offer a promising alternative to traditional methods. These tools are reshaping how forest inventories are conducted, especially in efforts to replace manual DBH measurement with more efficient approaches.

Close-range photogrammetry (CRP) plays a pivotal role in this technological transition. By generating 3D models from overlapping 2D images, CRP enables accurate reconstruction of tree trunks using basic digital cameras or smartphones. It provides a cost-effective solution for mapping and modeling forest plots. The flexibility of photogrammetry makes it particularly well-suited for integration into mobile workflows and forest monitoring applications.

Similarly, mobile and handheld laser scanners are gaining popularity as alternatives to traditional terrestrial laser scanning (TLS). Handheld sensors, such as the Stonex or Livox Avia, offer sufficient accuracy for estimating diameter at breast height (DBH) at a fraction of the cost and operational complexity. Comparative studies between handheld and TLS devices have demonstrated that, under certain conditions, handheld sensors can achieve accuracy levels comparable to those of more expensive systems, particularly in the assessment of individual trees [

9].

Among these, smartphones represent a rapidly emerging solution. Devices with built in LiDAR have demonstrated strong potential for generating high-density point clouds for accurate tree measurements, even in field conditions. For instance, apps leveraging mobile LiDAR or photogrammetry have achieved DBH estimations with errors as low as 2–3% [

10]. Gollob et al. [

11] reached RMSE 3.13 cm using iPAD Pro compared to traditional DBH measurements at various tree species. Similarly, Singh et al. [

12] achieved 2.58 cm 7.25% RMSE with iPhone Pro 12. Usage at monoculture potentially reaches better results. This fact underlines the work of [

13] who used iPad Pro at boreal forests of Canada reaching 1.1 cm 6.17% RMSE. In summary, these tools are affordable, widely available, and capable of streamlining data collection without specialized training.

In the past decade, advances in remote sensing have provided new tools, techniques, and technologies to support forest management, which have enabled low-cost and accurate forest productivity assessments [

14]. Remote sensing (RS) technologies represent an effective way to acquire relevant information about forest ecosystems [

15]. RS technologies, such as Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR), photogrammetry, and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), have demonstrated potential for providing accurate, efficient, and scalable solutions for tree trunk diameter estimation. For instance, ref. [

16] developed an autonomous system using a below-canopy UAV equipped with LiDAR to estimate tree diameters, achieving a high correlation with manual measurements. Similarly, ref. [

17] utilized UAV-mounted LiDAR to estimate forest structure parameters, including DBH, highlighting the efficiency of UAV-based laser scanning in forestry applications. Ref. [

18] used different methods of estimation of DBH using terrestrial laser scanning (TLS). Some researchers focus on developing custom instruments for measurement tasks, such as [

7], who designed a specialized device for measuring DBH.

Despite these advancements, challenges persist, including implementation costs, data processing complexity, and variability in environmental conditions that may affect measurement accuracy. Furthermore, comparative studies evaluating the efficiency and reliability of these technologies across diverse forest types and conditions are still limited. Addressing these gaps is crucial for advancing sustainable forest management and practices. Smartphone-based works [

10,

11,

12,

13] primarily benchmark one application or one hardware generation against manual DBH measurements, often under stand-specific or controlled conditions. Photogrammetry-oriented studies focus on performance within a single workflow or camera setup, while handheld LiDAR assessments [

9,

19,

20] compare individual mobile scanners to TLS but do not integrate smartphone LiDAR or ToF-based tools. As a result, cross-technology comparisons remain fragmented, and differences in field protocol, sample size, and environmental conditions limit direct comparability across studies. Only a few multi-method datasets exist, and these rarely evaluate smartphone LiDAR, smartphone photogrammetry, professional close-range photogrammetry approach, with low-cost and high-end handheld LiDAR within the same experimental context. Across the literature, there is a lack of studies conducted under identical acquisition geometry, identical environmental conditions, identical reference dataset, and consistent processing criteria. This gap makes it difficult to understand the true relative performance of these technologies and to identify sources of systematic variability, such as species effects, bark morphology, or algorithmic limitations.

This study explores the application of progressive technologies for estimating tree trunk diameter, focusing on the potential of smartphones and mobile handheld devices. By evaluating their agreement with conventional caliper measurements and overall efficiency, the research contributes to the development of more effective and accessible methods for forestry management and environmental monitoring. Specifically, the objective of this study is to compare a range of devices, from low-cost solutions such as smartphones and cameras to higher-class handheld mobile laser scanners, for generating 3D point clouds, identify factors influencing DBH estimation errors, and provide an overview that supports method selection in practice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

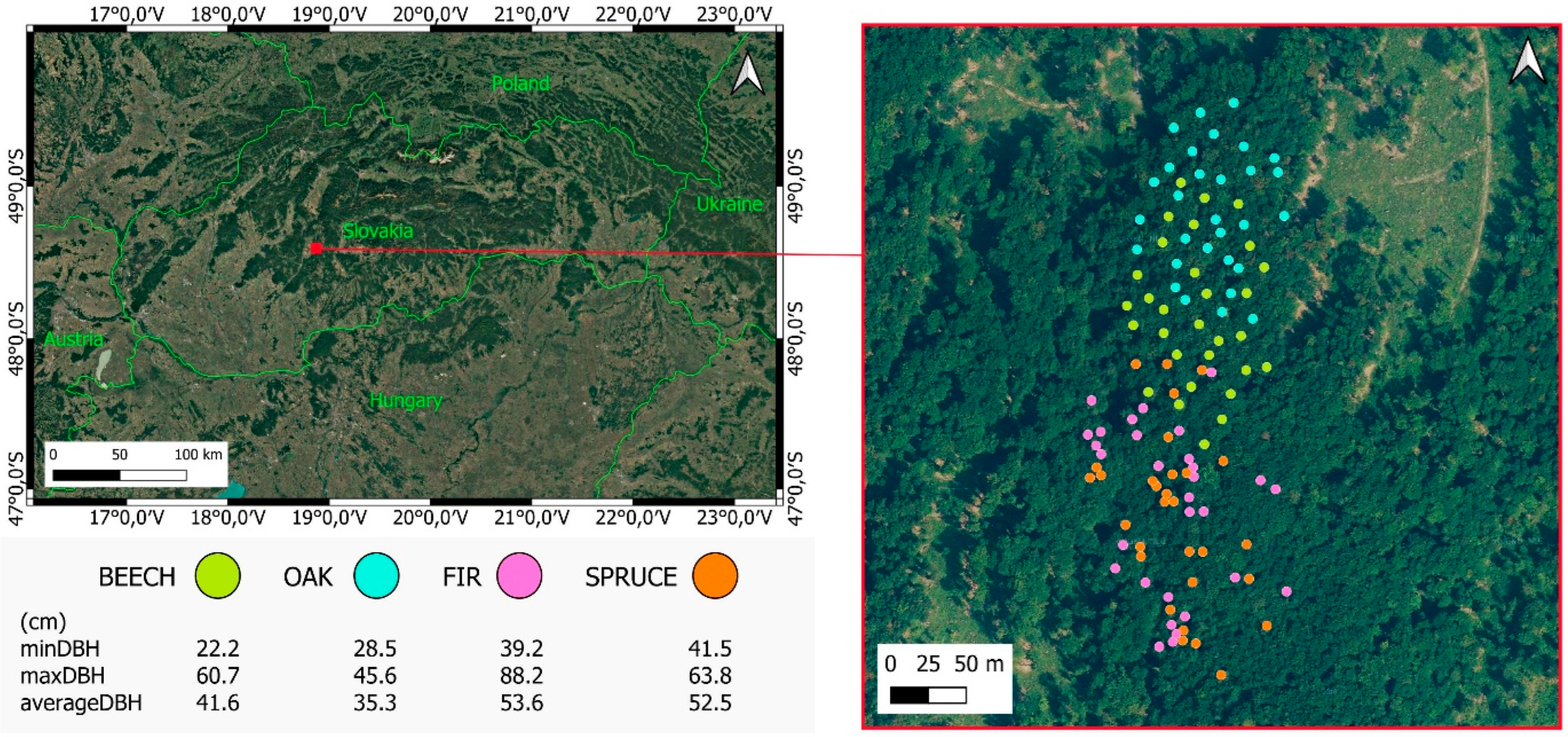

The study area is situated in central Slovakia, within the Kremnica Mountains. Forest stands in this region are characterized by a distinctive composition of tree species, notably European beech (

Fagus sylvatica L.), Sessile oak (

Quercus petraea (Matt.) Liebl.), Norway spruce (

Picea abies (L.) H. Karst.), and European silver fir (

Abies alba Mill.) (

Figure 1). These four species were also considered in our experiment, with an equal representation of 30 trees per species to account for differences in bark morphology. To maintain consistency, all specimens were evaluated under similar light conditions and gentle slope gradients (ranging from 0% to 5%). Tree ages varied between 55 and 100 years, with individuals from each species originating from a single, homogeneous forest stand to ensure uniform age distribution and environmental factors.

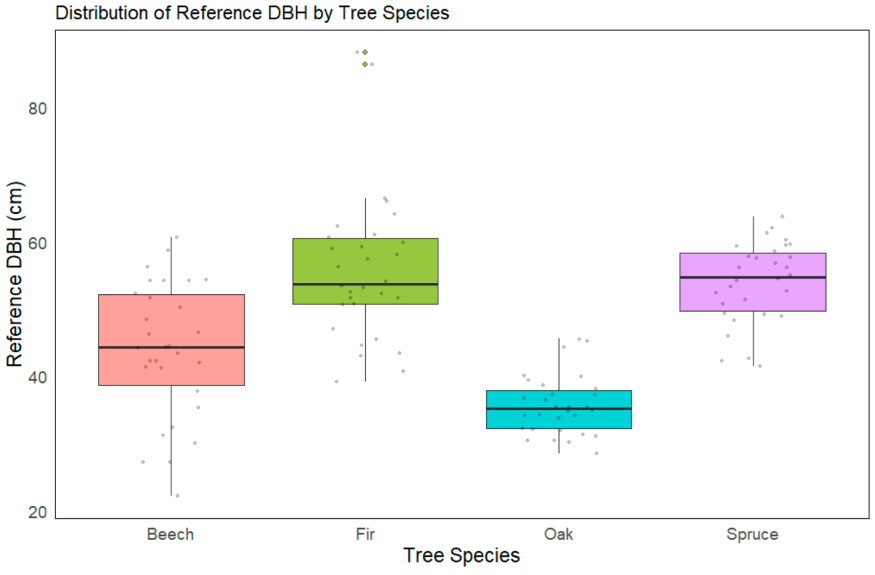

To characterize the structural properties of the sampled trees, descriptive statistics of the reference DBH values (caliper measurements) were compiled for each species (

Table 1). Across the full dataset (n = 120 trees), DBH ranged from 22.2 to 88.2 cm. Beech exhibited the widest DBH range (22.2–60.7 cm, mean 43.9 cm, SD 10.1 cm), followed by Fir (39.2–88.2 cm, mean 56.0 cm, SD 11.2 cm). Oak trees were more homogeneous in size (28.5–45.6 cm, mean 35.7 cm, SD 4.41 cm), while Spruce showed intermediate variability (41.5–63.8 cm, mean 54.0 cm, SD 5.97 cm). To visualize these patterns, boxplots of caliper-measured DBH were added (

Appendix A.1), illustrating the differences between-species in stem dimensions. These summaries provide important context for interpreting method-specific errors, as stem size distribution can influence both measurement stability and reconstruction performance. Although the tested trees had DBH above 20 cm, the evaluated methods are applicable to smaller stems as well.

2.2. Devices Under Evaluation

In this study, we used various devices representing different technological approaches to spatial data acquisition. The well-known handheld mobile laser scanner Stonex X120GO and a self-constructed low-cost handheld mobile scanner based on the Livox MID-360 sensor were benchmarked; both operate using simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM) technology. Photogrammetry was also used to obtain point clouds with a Sony Alpha 6300 camera and an iPhone 15 Pro Max. Since the iPhone 15 Pro Max is also equipped with an integrated LiDAR sensor, additional data was acquired using this sensor, specifically through the Forest Scanner and Arboreal mobile applications. The differences between these devices lie mainly in the method of data generation, the operational range, point density, the ability to accurately capture fine details, and cost (

Table 2), all of which significantly affect their applicability for various types of forest ecosystem monitoring and inventory.

2.2.1. Mobile Laser Scanning Devices

The Stonex X120GO (Stonex Srl, Milan, Italy) collects up to 1.2 million points per second, features a 360° rotating head, three 5 MP cameras, and a 200° horizontal and 100° vertical field of view, capturing both texture information and color point clouds. It offers real-time point cloud display via the GOapp (version 2.9.12.297, Stonex Srl, Milan, Italy) mobile application and includes post-processing software (GOpost (version 2.4.6.0, Stonex Srl, Milan, Italy)) for optimizing point cloud data (X120 GO SLAM Laser Scanner—Stonex).

The Livox MID-360 (Livox Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) is a compact LiDAR system designed for low-speed robotics, offering 360° horizontal and 59° vertical field of view. It features a minimum detection range of 10 cm, a maximum detection range of 40 m, and a 40-line point cloud density.

2.2.2. Photogrammetric Devices

The Sony Alpha 6300 (Sony Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), equipped with a Sony SELP1650 16–50 mm lens, is a mirrorless camera featuring a 24.2-megapixel APS-C Exmor CMOS sensor and fast hybrid autofocus with 425 phase-detection points. The camera supports 4K video recording and high frame rate options.

2.2.3. Combined LiDAR and Imagery Devices

The smartphone iPhone 15 Pro Max (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA) is equipped with a 48 MP main sensor camera (f/1.78), a 12 MP wide-angle and 12 MP telephoto lens and the Sony IMX591 LiDAR SPAD sensor (Sony Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The sensor has a resolution of 0.01 megapixels and a pixel pitch of 10.1 microns (Sony ISP from IMX591, 10.1 μm Pixel Pitch, 0.01 MP, Stacked Back-Illuminated Direct-Time of Flight (d-ToF) SPAD).

2.2.4. Mobile Applications for LiDAR-Based Data Acquisition with Smartphone

Arboreal is a Swedish app that operates exclusively on iOS devices (Arboreal. Available online:

https://www.arboreal.se/en/arboreal-forest/ (accessed on 10 March 2025)). With this app, users can select a specific center within a predetermined area and create a digital boundary. Within that boundary, users capture images of every tree, and the app prompts them to enter the height of a specified tree. Once all the data is collected, the app processes the information and generates a report containing all the relevant details—Diameter, Basal Area, Trees per hectare, Volume, Height or Tree species [

21].

3D Scanner App 1.8.1 (Laan Labs 3D Scanner App-LIDAR Scanner for iPad & iPhone Pro. Available online:

https://www.3dscannerapp.com/ (accessed on 10 March 2025)) is an advanced LiDAR scanning tool designed for iOS devices. It allows to capture detailed 3D models of objects and environments while also providing real-time editing and precise measurement capabilities (3D Scanner App).

ForestScanner is a mobile application for conducting forest inventories using LiDAR-equipped iPhones and iPads. The app operates on devices that include a time-of-flight LiDAR sensor with a maximum scanning distance of 5 m. As the user scans trees with the device by walking in the field, ForestScanner estimates the stem diameters and spatial coordinates in real time [

22].

2.3. Reference Data

Data collection took place during the period from September 2024 to February 2025. In total, DBH was measured on the 120 trees. The trees were numbered, and each tree was permanently marked at a height of 1.3 m (

Figure 2). Then, the DBH was measured at the marked position using a caliper.

Descriptive statistics of reference (caliper-measured) DBH values for each tree species are summarized in

Table 1. Beech exhibited a DBH range of 22.2–60.7 cm (mean = 43.9 cm, SD = 10.1 cm), whereas Fir showed larger trees with DBH ranging from 39.2 to 88.2 cm (mean = 56.0 cm, SD = 11.2 cm). Oak and Spruce displayed intermediate size distributions. The variability within and among species is further illustrated in

Appendix A.1, which presents boxplots of the reference DBH values. These visualizations provide context for interpreting species-specific differences in DBH estimation performance.

2.4. Data Collection

In our experiment, we performed measurements using nine different approaches. We collected images and videos with a Sony and iPhone camera, data from three LiDAR systems (Stonex, Livox, and iPhone scanner) and via three mobile applications using LiDAR integrated in the iPhone (3DScanner app, Arboreal, Forest Scanner). All measurements were taken from a single starting point relative to the tree being imaged.

2.4.1. Image and Video Acquisition—Sony a6300 and iPhone 15 PRO MAX

Before image acquisition, two A4 sheets printed with photogrammetric markers (24 per sheet) were installed on the prism pole and placed near the trunk (<1 m away). The targets were rotated in the opposite direction of the rounding tree (

Figure 3). These markers were used for scaling and orienting the point clouds. For scaling purposes, only one sheet was required, but multiple sheets were used to verify accuracy. For all approaches later processed by photogrammetry, each tree was circled at an approximate distance of 2 m from the trunk to ensure that the lower stem section and surrounding ground were sufficiently captured.

All devices were used with automatic exposure and focus settings to ensure optimal imaging conditions in the field. For both the iPhone and the Sony camera, ISO and focus were set to automatic mode to maintain consistency and minimize user-induced variability. No additional calibration procedures were applied beyond the internal factory calibration, as each device was used in its default configuration designed for standard operation. The data collection started and ended at the same point. The images were captured in the static position of the operator, and the distance between the positions was approximately 1 m. The average number of photographs was 15–20 and 20–30 frames were selected from video. The average time to collect the images was 1:02 min (Sony) and 0:52 min (iPhone). The resolution of the photos is 2624 × 3936 pixels (Sony) and 3024 × 4032 pixels (iPhone).

The collection of the video records took place immediately following the collection of the images, so the conditions were the same. Identically, the trunk was circled at approximately 2 m and the data collection started and ended at the same point. In both cases, the video was recorded in Full HD mode.

The average length of the record was 0:35 (Sony) and 0:37 min (iPhone).

2.4.2. LiDAR Data Acquisition—HMLSs Stonex X120GO and Livox MID-360

Prior to the actual 3D data collection for both HMLSs, a 5 × 5 × 10 cm wooden block was attached to the marker on the trunk. The wooden block was always placed precisely on the original pink marker. This method was chosen because we planned to use non-colored point clouds—they always have a higher point density than colored ones. However, in this case it would not be possible to identify the colored marker, for this it was necessary to create a geometric marker clearly recognizable in the point cloud.

The GOpost mobile application was used to control the HMLS Stonex X120GO. After the initialization of the scanner (one minute for each scan), the operator walked around the tree at approximately 3 m. In this case, the scan of one tree was relatively short due to the range of the device—approximately 30 s, but the device requires an initial initialization of 1 min for each collection. The scan was then completed, and the device was moved to the next individual tree, where the workflow was repeated. Approximately 1:30 min was spent on the scanning of one tree.

With the scanner prototype Livox MID-360 LiDAR sensor, the workflow was similar. After the initialization time, the scan was performed by moving at walking speed while the LiDAR sensor collected the 3D measurement data. The prototype was carried at a height of approximately 1.3 m with slight tilt to the tree, which ensured that both stems and the ground could be captured. The device requires an initial initialization of 25 s for each collection on average. The scan took approximately 1 min per tree.

2.4.3. Mobile Apps’ Data Acquisition—3Dscanner App, Arboreal, ForestScanner

The tree was walked around in the same way as in the previous cases, taking care to keep the device at a height of approximately 1.3 m and the iPhone sensor’s ability to scan up to 5 m. This procedure ensured accurate capture of the part of the trunk where the DBH would be measured as well as the ground. Movement around the tree was carried out so that the base of the tree was reliably recorded along with the surrounding surface. Arboreal and Forest Scanner do not require post-processing on a PC as the tree data is available immediately after the target tree is scanned. The 3D Scanner App, on the other hand, requires additional processing to extract tree-level information. The settings of the available parameters in the ForestScanner app were the range set to 5 m and the resolution to 20 mm. The average time to collect the data was 3 s for all apps.

2.5. Data Processing

2.5.1. Image and Video Postprocessing

Processing of images to point clouds was performed using Agisoft Metashape Version 2.1.2 (Agisoft LLC, Saint Petersburg, Russia). When processing photos from the Sony Alpha 6300 and iPhone 15 PRO MAX, 15 to 20 photos were used for each tree (

Figure 4A).

When processing the video records from the previously mentioned devices, 20 to 30 of the most focused frames, individually selected from the original video for each specific tree, were used to produce the point cloud (

Figure 4B). Every fifth frame was extracted from the video sequence and visually checked to avoid motion blur or defocused images.

All images were aligned with “High quality”. Point cloud alignment was performed automatically using feature-based image matching and bundle adjustment optimization (

https://www.agisoft.com/pdf/metashape-pro_2_0_en.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025)). After alignment, we manually searched for markers that were placed on the prism pole next to trunks. Markers were used to scaling the point cloud—scale adjustment to the real dimensions of the object. Then, colored dense point clouds of all individual trees were performed. For photogrammetric datasets, scene scaling was performed using printed A4 reference markers placed near the tree trunks during image acquisition. The photogrammetric markers (A4 sheets) were exported directly from Agisoft, which contained fixed geometric parameters ensuring metric accuracy. Although the use of printed scale markers is not strictly required for photogrammetric processing, they were applied to ensure reliable scaling of the reconstructed models, as recommended in standard SfM workflows [

2]. Processing of the photogrammetric material took approximately 5 min per tree.

2.5.2. HMLSs’ Data Postprocessing

The Stonex HMLSs 3D data were pre-processed in GOpost software. The SLAM algorithm was applied to the raw field record resulting in a dense point cloud. On average, each record took 3:40 min to process.

The prototype data with the Livox sensor was processed identically by the SLAM algorithm in our software. The processing of individual cloud points took on average 1:58 min.

To ensure the highest level of comparability between the HMLSs, uncolored point clouds were used. This approach was justified by the fact that the colored Stonex point cloud has a reduced density, and the prototype with the Livox sensor does not yet include a camera, making colorization impossible at this stage of the research.

2.5.3. Mobile Apps’ Data Postprocessing

In the case of mobile apps, postprocessing of point clouds was not performed, as the apps do not allow the application of advanced algorithms for realignment (3D Scanner App) or display tree data directly in real time (Arboreal and ForestScanner App).

2.6. DBH Estimation

For DBH estimation, our aim was to replicate a real DBH measurement using a caliper in the field and to ensure that the measurement was taken at the same point as the reference DBH. To achieve this, we used the position of the markers sprayed on the trunks for photogrammetry-based point clouds and the position of the wooden block for LiDAR-based point clouds.

Initially, five two-centimeter-high cross-sections were extracted from the point clouds within the height range of 1.25 to 1.35 m using the DendroCloud software [

23]. Subsequently, the cross-section that corresponded to the physical DBH mark on the tree (approximately 1.3 m above the ground) was selected for further analysis. A digital elevation model (DEM) with a grid size of 0.2 m was created to ensure consistent height reference, where the minimum Z value was assigned from the point cloud. The points within the cross-section were spatially grouped, and a circle-fitting algorithm was applied to determine the initial diameter and position of the tree. The Optimal Circle method with the automatic initial method was used for this process, with further details available in [

2,

23,

24].

Next, a normalized DEM was calculated based on tree position and diameter, allowing the generation of multiple cross-sections at specified heights. The points at each height were spatially grouped, resulting in five cross-sections per tree (1.25, 1.27, 1.30, 1.32, and 1.34 m). The results were exported in csv format and subsequently imported into QGIS.

Cross-sections were checked and the one with the visible mark was selected for DBH measurement. All cross-sections point clouds imported into QGIS for Desktop, and the Minimum bounding geometry module was applied.

Meanwhile, for each tree, the location of the color marker or wooden block was identified in CloudCompare and exported as an individual point with X, Y, and Z coordinates. These points represented the exact locations where the DBH was measured.

The exported points were then imported into QGIS along with the cross-section point clouds. Finally, the DBH was manually measured at the same position and in the same direction as in the field using a caliper (

Figure 5). In the DBH estimation, we followed the methodology published in our previous research [

2].

2.7. Data Evaluation

For each technology, estimated DBH was evaluated. The Root Mean Squared Error (

RMSE) (Equation (2)) and relative Root Mean Squared Error (

rRMSE) (Equation (3)) were calculated to compare results obtained from used technologies and field reference data. The statistical analysis was conducted using R software version 4.3.3.

where

Yi is the actual observation (m),

is the estimated observation (m), and

N is the total number of observations.

Statistical analyses were performed using R software (R Core Team, 2024).

For each species and method, paired

t-tests [

25,

26] were performed to assess differences between observed values and the reference measurements. The mean difference, confidence intervals, and

p-values were extracted from test results, with statistical significance determined at

p < 0.05.

In addition to paired t-tests, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to assess the effects of species and estimation methods on measurement errors. A two-way ANOVA model was constructed to examine the interaction between species and estimation methods, followed by a separate ANOVA to analyze differences in errors across estimation methods. Post hoc comparisons were conducted using Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (TukeyHSD) test to identify specific differences between methods (R Core Team, 2024).

3. Results

3.1. Point Cloud Density

Prior to the analysis of the trees’ diameters, an evaluation of point cloud density and quality was conducted.

Table 3 shows the acquired values for all data acquisition methods besides the Arboreal and ForestScanner applications, where the diameter was measured directly in the application without exporting the point cloud. The number of points in a 10 cm cross-section clearly shows significantly higher density for point clouds based on photogrammetric methods compared to laser scanning. The density of points determined using photogrammetrically processed iPhone 15 PRO MAX imagery is ~70 times higher than the density acquired using the laser scanner of the same device. The number of photogrammetrically derived points is apparently in close relation to the device’s resolution, considering 48 megapixels for the iPhone and 24.2 MPx for the Sony camera.

While photogrammetric approaches produced cross-sections with very high point density (

Figure 6), LiDAR-based methods resulted in sparser reconstructions, in line with the numerical comparison (

Table 2). Examples of LiDAR-based cross-sections are provided in

Appendix A.1.

Within photogrammetric approaches, higher point density did not necessarily result in a qualitatively different representation of the trunk surface, as both the iPhone and Sony Alpha reconstructions appeared visually comparable despite a nearly two-fold difference in density. The implications of this observation for DBH estimation are addressed in the following section.

3.2. DBH Evaluation

The quality of point clouds influenced also the determined diameters at breast height, which are the main focus of the study. The results indicate that the DBH estimation errors vary slightly among species (

Table 4), with Oak and Fir showing relatively higher mean errors compared to Beech and Spruce. The standard deviations suggest moderate variability across all species.

Figure 7 summarizes the results of all evaluated methods, including the applications able to measure the DBH directly (Arboreal, ForestScanner, see

Appendix A.3 for detailed regression and error statistics). The results show distinct differences between the photogrammetric- and LIDAR-based data, both in the mean values and the variability. The medians vary from a few millimeters to ~6 cm and are influenced by both data collection methods and tree species. The inter quartile ranges (IQR, between 25 and 75 percentile) typically reach a few millimeters for photogrammetry-based methods, sub-centimeter levels for handheld scanners and the Arboreal application, and up to five centimeters for 3DScanner and ForestScanner applications. The higher errors reach up to ten centimeters. DBH overestimation is generally apparent for the majority of the methods and tree species. This is most probably related to the point cloud noise and subsequent circle fitting procedures. The exception to this observation is the behavior of the Arboreal application, which underestimated the DBHs of three species, and the ForestScanner application, which underestimated DBHs of Beech. Some cases of underestimation can also be observed for photogrammetric methods, but here the median errors and even IQRs are very close to zero (see

Appendix A.4 and

Appendix A.5).

3.3. Method Comparison

Already indicated differences between the methods are also proven by comparing overall Root Mean Squared Errors without taking the tree species into account (

Figure 8). For this purpose, the methods have been sorted into three groups—scanning applications with the DBH measurement directly in the mobile application, laser scanning processed in a PC, and photogrammetric methods. Generally, the laser scanning methods provide RMSE up to ~2 cm, with the exception of the 3DScanner application where the application results are directly measured in an RMSE of 5.3 cm, while processing of the 3DScanner point cloud in a PC provided a 4.5 cm RMSE. In this case, the processing involved importing the point cloud from the 3DScanner application into a PC environment, extracting a 2 cm-thick cross-section at the DBH mark, and fitting a circle to derive the stem diameter. These additional steps allowed more precise control of section positioning and circle fitting compared to in-app processing. Slightly better results of the PC processed point cloud could be partially attributed to better display and control conditions compared to handheld devices. The low-cost laser scanner (Livox MID-360) provided results comparable to a commercial handheld laser scanner (Stonex X120GO).

The RMSEs of photogrammetric-derived point clouds are surprisingly similar. Although all of these sub-centimeter values could be considered the same from the practical point of view, the best result of the video-based point cloud acquired using iPhone is interesting. Apparently, the two-times higher point cloud density acquired using the iPhone camera did not have a significant impact on the resulting accuracy, comparing it to the Sony camera results. It could be assumed that increasing the point cloud density beyond a specific value has no positive effect. Determination of such a density, taking also the quality of the points into account, could be a significant optimization factor.

Regarding the statistical significance of the differences against the reference (

Appendix A.2), the analysis showed that the mean errors of the video-based methods (both Sony and iPhone) are not significantly different from the reference. Mean differences in other methods are significantly different from the difference.

Also, the differences between devices and methods were tested. As shown in

Figure 9, the 3DScanner software was significantly different from all other methods, considering both processing scenarios—i.e., DBH determination directly in the application and using the acquired point cloud in PC. The differences between photogrammetry-based methods are insignificant. The comparison between handheld laser scanners (Stonex and Livox) does not show significant differences.

3.4. Influence of Tree Species

Besides the differences between the methods, the differences between the tree species were also evaluated. Taking the overall results without considering specific methods, the results for Beech are significantly different from Fir and Oak (

p = < 0.001). Also, the errors for Spruce are significantly different from Oak (

p = < 0.001) and Fir (

p = < 0.01) (

Table 5).

An assumption that the bark structure will have an apparent influence on the DBH accuracy has not been fully proven. Considering Beech as the species with the least structured bark from the selection, the photogrammetric point clouds provided the best results with the exception of video data from Sony camera. However, it must be noted that also for other species these point clouds provided sub-centimeter accuracy (

Figure 10). On the other hand, the accuracies for Beech were above the average for the 3DScanner (both in-app and point cloud measurements), where the RMSEs compared to Spruce and Oak even exceeded one centimeter. Such a difference could be considered significant from the practical point of view. Regarding the 3DScanner, the highest RMSEs were observed for Fir, which also has relatively low-structured bark. The results for Oak as the species with the most structured bark from tested species are consistent within the groups of methods, excluding the aforementioned 3DScanner. Even for the ForestScanner app, where the RMSEs of other species exceeded two centimeters, the RMSE for Oak is 1.63 cm, thus very close to RMSE achieved using the Arboreal app. For other species, especially Spruce and Beech, the Arboreal provided apparently lower RMSEs compared to ForestScanner. Regarding the handheld laser scanners, the best results were achieved for Spruce with RMSEs lower than 1.4 cm. However, the results for other species are different only by few millimeters and for all species the handheld scanners provided errors between 1.2 and 1.6 cm.

3.5. Influence of Method

The largest mean differences were observed for mobile applications (

Figure 11—green), especially for the 3D Scanner App, where the differences exceeded 5 cm. HMLS devices (

Figure 11—blue) produced more stable results with less variability, while photogrammetric methods (

Figure 11—red) showed the smallest differences and highest accuracy. The results also indicate a significant influence of tree species, with Fir, for example, tending to show greater differences with mobile applications. Overall, photogrammetry provides the most accurate and consistent results across tree species, whereas mobile applications exhibit higher variability and larger deviations.

The most significant factor influencing the accuracy of DBH was the method used (

Table 6), indicating significant differences between methods. Tree species also had a significant, although less pronounced, effect, suggesting that the characteristics of different tree species may influence the quality of the results. There was also a statistically significant interaction between method and tree species, indicating that the accuracy of individual devices (

Section 2) may vary depending on the specific tree species.

3.6. Overall Assessment

Besides achievable accuracy, the difficulty to use and price are the most prevalent factors for the user when choosing an appropriate method for a particular task. These factors plus the time needed to data collection and processing were rated using relative marks from 0 to 1, where the lower is the better. These ratings are summarized in

Figure 12.

In addition to achievable accuracy, the most important factors in selecting a suitable method for determining tree height and diameter include ease of use, cost, and time efficiency. As

Figure 12 shows, the shortest data collection time (3 s) was recorded with the Forest Scanner application. Data processing was fastest for applications such as the 3D Scanner App and slowest for photogrammetric methods (5 min).

Most of the tested methods are using the iPhone Pro hardware, i.e., camera or LIDAR sensor. Thus, the device price is the same. However, for photogrammetric methods the cost of photogrammetric software must be taken into account, and the Arboreal application is paid. The photogrammetric methods provided the best DBH accuracy, but these are generally highly time-consuming in the phase of data collection and processing, and the difficulty of use is the highest from all tested methods. This is mostly related to the complicated methodology of data collection and processing. LIDAR-based iPhone applications provided significantly different results. Applications specialized in forest measurement use automatic tree detection in real time, therefore there is no need for post-processing the data. The collection of data is the fastest and also the difficulty of use is low. The paid Arboreal application provided a slightly better overall RMSE (1.6 cm) than the free ForestScanner app (2.1 cm). On the other hand, the general purpose 3DScanner application suffered from the highest DBH errors and the time-consumption and difficulty of use is higher, mostly because the need to identify and manually measure the DBH in the application or in the point cloud processed in PC.

Regarding the point clouds acquired using the Sony A6300, most of the conclusions given for iPhone photogrammetric data can also be applied here. The point clouds provide high spatial accuracy but are difficult to obtain. Comparison of photo and video approaches shows that the collection time is lower for video, but it demands more processing time due to the need to select usable frames. Although the photogrammetric approaches using both iPhone Pro and Sony A6300 camera came very similar from this comparison, it must be noted that the Sony camera is in principle a single-purpose device as opposed to the smartphone, which can be used for many other tasks.

Handheld laser scanners directly provide point clouds, which can be visualized and processed in a variety of general-purpose (e.g., CloudCompare) or specialized (e.g., DendroCloud (version 1.52, Technical University in Zvolen, Zvolen, Slovakia)) software. Taking the specific task, i.e., DBH determination, and the comparison with other tested methods into account, the handheld scanners demanded relatively high time consumption and were difficult to use, but provide only middling DBH accuracy of ~ 1.5 cm. However, there is an unmissable difference in prices. The Stonex X120 GO is by far the most expensive of the tested devices, with a price more than 20 times higher than other devices. The low-cost Livox Mid360 handheld scanner provided comparable demands and accuracy of single tree DBH measurements. The higher collection and post-processing time for the Stonex scanner is caused mainly by the need to initialize the device before every measurement (which takes exactly one minute), while the subsequent processing in the GOpost software adds only a minor delay. Thus, the Stonex scanner cannot be considered ideal for this task. However, the situation could significantly change in the case of need for complex forest scanning and, e.g., determination of tree heights. Generally, handheld laser scanners could be more efficiently applied to capture the complexity of wider areas, rather than the dimensions of single objects.

4. Discussion

Can we sufficiently measure the individual tree diameter at breast height with the proximal sensing approaches? Does it make sense, and is it efficient? And is it really an alternative to a caliper? These were the main questions we asked, and we created the experiments shown in the paper. Within the field of proximal sensing, we are seeing an extraordinary development. We can create a three-dimensional representation of the bottom part of the tree trunk with a wide range of sensors that are based on lidar or images. Here we have benchmarked those with the highest potential and given the answer on which one is the most accurate, but we also looked at the efficiency. It should be noted that the reported accuracy reflects the agreement with caliper measurements rather than the absolute accuracy. Calipers were used as the reference method for DBH determination; therefore, RMSE and other error metrics express the consistency between each tested approach and this conventional method. We can clearly see that those based on images and photogrammetry are giving us superior accuracy and reliability. Although photogrammetry provided the most precise DBH estimates, it required manual scaling using A4 reference markers, which added an additional step to the workflow and reduced operational efficiency compared to single-step approaches such as calipers or mobile applications. We can only use the images or frames from video using just a smartphone, and the accuracy and reliability against commercial or low-cost handheld scanners will be significantly higher. In the current development of computational power of smartphones, it is better to focus on the implementation of algorithms that process images or frames to point clouds and calculate the DBH based on these point clouds instead of relying on those from ToF sensors in the iPhone. It is more reliable, but you also do not need to rely on iPhone Pro and Pro Max that have ToF sensors and can spread the application across iOS and Android devices.

4.1. Accuracy or Agreement with the Caliper?

In this paper, we decided to evaluate the agreement of our results with conventional measurements (caliper). In a wide range of papers, this is usually referred to as accuracy or precision [

27]. The question is what the truth actually is. We have not explored this in a deep sense, but we believe it is worth mentioning. We can assume that the truth of the diameter at breast height is very near to the caliper measurements, and then what is near to these measurements is also near to the real-world truth. For this assumption, we have compared our results against the measurement conducted in the field by a caliper at the same position using a marking on the trunk, so we minimized the errors from the different positions on the trunk. This marking helped us to compare exactly the position across all used technologies. In a pure sense, this is a comparison of two approaches and their difference or level of agreement and not the accuracy.

4.2. Comparison with Previous Papers

Here we have taken a range of technologies and methods that can be divided into those based on active and passive sensors. And our goal was to measure individual trees and not to focus on the whole plot. There have been multiple papers published on the iPhone/iPad possibilities to measure the DBH using the ToF sensors [

11,

28,

29], and in the past, very similar experiments and sensor tests were performed using Google Tango [

30].

The agreement with our results is comparable and shows that DBH measurements using such approaches usually do not exceed a relative RMSE of about 20%. For instance, Brach et al. [

28] reported an RMSE of 6 cm (≈7–8%) when using a low-cost LiDAR scanner, while Fan et al. [

29] achieved a RMSE of 1.26 cm (6.4%) with a smartphone using RGB-D SLAM. Similarly, Gollob et al. [

11] found an RMSE of 3.13 cm when measuring DBH with an iPad Pro LiDAR, and Tomaštík et al. [

30] obtained an RMSE between 1.6 and 2.1 cm using the Google Tango device.

When looking at image-based DBH measurements from photogrammetric point clouds, the agreement with conventional methods is also strong. The challenge here is the importance of correct scaling, since 2D images alone cannot provide a metric reference. This distinguishes passive image-based methods from active sensor-based approaches, where scaling is inherently embedded in the measurement. For example, Mokroš et al. [

2] achieved RMSE between 0.4 and 0.7 cm for diameter using close-range photogrammetry with georeferenced targets, and below 2% in relative terms.

The use of photogrammetry and its workflow also introduce an additional processing step, where images must be converted into scaled point clouds. This step has been shown to be decisive, as Structure-from-Motion workflows with properly implemented scaling can achieve error levels comparable to active sensors [

31], for example, reported RMSE values of 1.1–1.4 cm for straight stems and up to 3.2 cm for irregular shapes. These findings further support that photogrammetry can provide highly accurate DBH estimates when the workflow is well designed.

At the same time, increasing point cloud density beyond a certain threshold does not necessarily improve the accuracy, as shown by the comparable results of iPhone photogrammetry and the Sony camera despite the two-fold difference in point density (

Table 3). This suggests that, rather than absolute density, the decisive factor is the quality of the processing pipeline and scaling.

In our experiment, the higher accuracy of photogrammetric approaches compared to smartphone-based LiDAR can be explained by a combination of technical factors. Multi-view photogrammetry captures substantially richer surface information, as each image contributes fine-scale texture and geometry, resulting in dense and smooth stem reconstruction even from simple circular acquisition paths. In contrast, the LiDAR sensors integrated in mobile phones produce relatively sparse depth maps with limited effective range and coarse spatial sampling, which leads to incomplete and noisy trunk geometry. Photogrammetric workflows also allow explicit user control over scaling, alignment, and reconstruction parameters, whereas mobile LiDAR applications rely on fixed, simplified pipelines that restrict user control and may introduce systematic biases. Our results, together with previous studies [

11,

20,

28,

31], indicate that once point cloud density exceeds a critical threshold, additional points do not substantially improve DBH accuracy—the limiting factor becomes the inherent resolution of the depth sensor and the constrained mobile processing workflow. These mechanisms jointly explain why, for single-tree measurements at short distances, image-based point clouds outperformed ToF-based LiDAR in our study.

Recent studies have shown that the relationship between point cloud density and geometric accuracy is nonlinear, with a saturation effect once a critical density threshold is reached. Beyond this point, additional data do not significantly improve reconstruction quality or DBH accuracy, but rather increase redundancy and processing noise. For example, [

32] reported that DBH estimation accuracy stabilizes below 1 cm RMSE at point densities of approximately 600–700 points m

−3, while tree height accuracy plateaus around 300 points m

−3. Similarly, [

33] demonstrated that image-based reconstruction accuracy reaches its optimum when image overlap exceeds 95% and ground sampling distance is finer than 5 cm.

More recent studies using LiDAR-equipped smartphones further contextualize our results. Reference [

34] reported very low errors (MAE 0.53 cm, RMSE 0.63 cm) for an iPhone 13 Pro using a single-shot depth–RGB workflow under controlled conditions and at capture distances up to 5 m. In contrast, [

13] achieved an RMSE of 1.5 cm (8.6%) and an MAE of 1.1 cm (6.4%) when applying an iPad Pro LiDAR scanner across natural boreal forest stands with varying tree density and understory conditions. Our ToF-based applications on the iPhone 15 Pro Max yielded RMSE values between 1.6 and 5.3 cm, which overlaps with the operational error range reported by [

13] and remains higher than the best-case performance documented by [

34]. These comparisons suggest that although smartphone LiDAR can achieve sub-centimeter accuracy under favorable and carefully controlled conditions with dedicated algorithms, its performance in heterogeneous forest environments typically falls within the range of 1–3 cm RMSE and may further deteriorate when relying on general-purpose or less optimized mobile applications.

Overall, the consistency and deviations observed between our results and previously published studies can largely be explained by differences in sensor characteristics, acquisition distance, bark texture, and the degree of user control available in each processing workflow.

4.3. Plot vs. Individual Trees

It is important to distinguish between the measurements of DBH when the whole plot is scanned, vs. when we only focus on individual tree scanning. This is important regarding the accuracy of the measurements and also the quality of the point clouds [

35,

36,

37,

38]. When the whole plot is scanned, the focus is usually to cover the plot, and multiple trees can be covered poorly due to the occlusion, but also because of the distance from the scanner or camera. So, we can have trunks that are reconstructed quite well from one side but poorly from the other side due to the various distances of the operator from the trunk itself. Furthermore, mismatches of trunks also happen in cases when the software to pre-process the point clouds is not aligning the point cloud properly. These attributes are influencing the accuracy and the lower agreement with conventional methods. And we can see higher variability across papers and experiments [

9,

37], since plot-level scanning often suffers from partial trunk coverage and occlusion effects, resulting in higher RMSE values (typically >2 cm) compared to individual-tree scans where the operator can encircle each trunk and maintain optimal distance and overlap.

4.4. Tree Species Effect

Differences in DBH estimation are not only a matter of the method itself but also of the tree species and stem morphology. Variability in bark structure and stem surface influences the stability of the diameter estimation and can lead to systematic deviations between species. Beech and Fir, with less structured bark, showed larger discrepancies in some methods compared to Oak, which has a more distinct bark relief. The statistical interaction between method and species indicates that the reliability of each device is not universal but depends on the morphological properties of the measured trees. This emphasizes the need for testing across a wide range of forest conditions before any of the proximal sensing approaches can be considered for operational use. Although bark structure is often expected to influence the quality of LiDAR returns, our results indicate that this relationship is not straightforward and is strongly method-dependent. In the case of the 3DScanner application, Fir, despite its relatively smooth bark, showed the highest errors, suggesting that algorithmic processing, sampling pattern and partial trunk coverage can outweigh the effect of bark texture alone. Therefore, species-specific differences in our study should be interpreted as a combined outcome of bark morphology and method-specific limitations rather than a simple function of surface roughness.

In this context, the species–method interaction observed in the ANOVA should not be interpreted as a biological effect of species per se, but as a technical interaction between bark morphology and device-specific processing. Smooth-barked species such as Fir produced larger errors in the 3DScanner application not because smooth surfaces are inherently problematic, but because low-texture regions reduce the stability of depth-frame alignment in ToF-based mobile workflows. When fewer geometric or radiometric features are available, the application relies more heavily on internal filtering and interpolation, which can amplify small registration inaccuracies into larger diameter biases. This explains why Fir exhibited higher errors in our dataset despite its simple bark structure, and why the effect was not consistent across all methods [

11,

29,

39].

4.5. Processing Using Near-Manual Measurement

The processing solution has a significant influence on the accuracy of the DBH measurements. The push to fully automatic processing solutions is meaningful, but it can also introduce higher errors when no manual intervention is performed. In general, we can see that the processing solution has a significant influence on the accuracy of DBH measurements from point clouds. One example is the results of international benchmarking on terrestrial laser scanning for forest inventory. Where the relative RMSE of DBH varied from 5% to more than 150% across processing solutions when the same plots have been processed [

37].

4.6. iPhone as a Caliper Alternative

The implementation of iPhone scanning to inventory started around 2021 when Apple decided to include a time-of-flight sensor in their iPhone Pro and Pro Max. The first model was the 12. The development in this area is performed well since the library to control the sensor is open for developers. There are multiple applications developed purely for inventory purposes [

22,

40]. One example is the commercial application, and also the most used in practice, the Arboreal (

https://www.arboreal.se/en/arboreal-forest/ (accessed on 2 October 2025)). There are also other ones that have been developed by researchers to test the potential. From the published papers, we can see that the accuracy of the DBH measurements varies, but it shows a potential for practical implementation [

11,

12,

41,

42]. Using an iPhone as a caliper brings multiple pros. Firstly, foresters need to have a phone anyway. There are other sensors that are used, for example, to establish boundaries of a 500 m

2 plot or gyroscope can be used to measure height of a tree. Images captured by the phone can be used for tree species classification and more.

4.7. Variability Across Mobile Applications

Photogrammetric approaches provide consistent sub-centimeter accuracy (

Figure 8), while mobile applications are characterized by much higher variability and systematic deviations (

Figure 9). The largest discrepancies were observed for general-purpose tools such as the 3DScanner, whereas specialized forestry applications like Arboreal or ForestScanner delivered more stable results and are therefore closer to potential operational use, even though their accuracy remains lower than that of photogrammetry. The comparison of methods further indicates that the absence of statistically significant differences does not necessarily reflect comparable accuracy. In the case of Arboreal and ForestScanner, the relatively high variability leads to overlapping confidence intervals with photogrammetric approaches (

Figure 9). This overlap masks the systematic deviations that are apparent when comparing absolute error values and suggests that the reliability of these applications is less stable across individual trees. Multiple studies have shown that discrepancies between smartphone-based DBH applications arise not from the sensor itself, but from differences in how individual apps process depth data. Gollob et al. [

11] demonstrated that trunk segmentation and diameter-fitting algorithms vary substantially across applications, resulting in inconsistent DBH estimates. Similarly, Gülci et al. [

43] observed that point density and depth-map completeness differed between applications using the same iPhone LiDAR sensor, suggesting that internal sampling strategies strongly influence measurement stability. Ref. [

28] further showed that ARKit’s depth filtering affects the usable point cloud differently depending on the application. Together, these findings indicate that algorithmic implementation, not hardware limitations, is the primary source of variability between smartphone applications. These published findings are consistent with our results, where applications using the same iPhone LiDAR sensor produced substantially different point densities and DBH estimates, confirming that algorithmic implementation rather than sensor hardware is the main source of variability.

4.8. Have We Found an Alternative to the Caliper?

It depends. If the question is whether some of these approaches can be used as an alternative to caliper when we do not consider the possibility of measuring other parameters and are solely used for DBH measurements, the answer, in our opinion, is no. To consider any of these approaches as an alternative to measure DBH as the only parameter just does not make sense from multiple points of view. The caliper is efficient and easy to use in the field. There is no additional data needed to be stored and processed as is in most of the proximal sensing approaches. The random error occurs at a higher frequency across proximal sensing approaches. And finally, maybe the most important one, the practical implementation and convincing the forestry sector to use these technologies instead of the caliper is a challenging process, and we believe that we do not have strong evidence to do so.

The other question is whether these technologies should be used if other important parameters are measured from point clouds and are helping to make the inventory process sufficient. For example, to measure the tree height, crown parameters, tree species, count trees and obtain their position within the inventory plot, and similar. For example, within the national forest inventory in Slovakia, foresters are measuring more than 100 parameters within a 500 m2 plot. In this case, the switch to some of the proximal sensing approaches seems like the right step.

4.9. Accuracy, Time, and Cost Trade-Off

Practical deployment of DBH estimation methods depends strongly on the balance between precision, time, cost, and ease of use (

Figure 12). Photogrammetric approaches provide the highest agreement with caliper, but they require careful data acquisition and time-consuming processing.

Mobile applications are fast and easy to operate, yet they show higher variability and systematic errors (

Figure 10). Most general-purpose scanning apps are free of charge, but their inconsistent performance, with deviations of several centimeters, limits their practical value. Within forestry-oriented applications, Arboreal requires a subscription, but the associated cost is modest compared to dedicated hardware and is accompanied by higher stability and lower errors than the free ForestScanner. This illustrates that, even among mobile solutions, precision often comes at a price, though still far below the costs of handheld scanners or professional devices.

HMLSs stand in between, offering moderate accuracy but at considerably higher costs, which may only be justified when more complex forest structure information is needed. Their longer collection times are primarily due to hardware initialization (about one minute for the Stonex and around 25 s for the Mid360), with additional time required for data post-processing. This substantially increases the effective time per tree. The financial aspect also plays a role, as commercial devices such as the Stonex X120GO reach prices around USD 30,000 with proprietary software included, whereas low-cost alternatives like the Livox Mid360 rely on processing tools that are not yet broadly available. This underlines that the choice of a method cannot be guided by accuracy alone, but by the overall trade-off between precision, usability, cost, and software availability.

When comparing these approaches to the caliper, the contrast becomes even clearer: the traditional method is inexpensive, fast, and simple to use in the field, with errors that are typically negligible for operational purposes. The caliper therefore remains the most efficient option when DBH is the only parameter of interest, and it sets the baseline against which the cost and complexity of proximal sensing methods must be evaluated.

5. Conclusions

The evaluation of proximal sensing approaches demonstrated clear differences in both the agreement with caliper and the consistency of DBH estimation. Photogrammetric methods provided the highest agreement with reference values, often reaching sub-centimeter levels, while mobile applications showed greater variability and systematic deviations. Handheld laser scanners occupied an intermediate position, but with considerably higher costs that limit their practical justification for DBH alone. The results further revealed that species-specific traits such as bark structure influence the stability of the measurements, and that the reliability of each method depends on both the device and the morphological properties of the trees. From a practical perspective, the selection of a method cannot be guided by accuracy alone, but by the overall balance between precision, time, cost, and ease of use. When DBH is the only attribute of interest, the caliper remains the most efficient solution. Since bark texture can affect point cloud quality and diameter estimation, further validation across a broader range of species and bark types is recommended to confirm the robustness and general applicability of the presented approach. However, the potential of proximal sensing lies in the broader context of forest inventory, where multiple structural parameters can be derived simultaneously and the integration of these technologies can meaningfully enhance the efficiency of data collection. Beyond accuracy, practical adoption will depend on factors such as device cost, software availability, and the stability of mobile applications, with specialized solutions (e.g., Arboreal, HMLS with bundled software) offering more reliable results than general-purpose or experimental tools.

In the context of multi-parameter forest inventories, the comparison of tested methods highlights clear advantages and limitations that are relevant for practical deployment. Photogrammetric workflows provide the highest accuracy at low cost but require additional processing time and controlled acquisition to ensure proper scaling. Smartphone-based LiDAR applications offer fast, simple, and low-effort measurements, but their accuracy is limited by sparse depth sampling and closed processing pipelines, making them more suitable for rapid assessments rather than precision inventories. Handheld laser scanners provide richer 3D structural information and are advantageous when multiple attributes (e.g., height, crown shape, stem form) are required, though their high price and longer operational time reduce their practicality for single-parameter tasks such as DBH estimation. These trade-offs emphasize that method selection in forest inventories depends not only on accuracy, but also on the balance between cost, efficiency, and the breadth of structural information needed.