AWM-GAN: SAR-to-Optical Image Translation with Adaptive Weight Maps

Highlights

- The proposed AWM-GAN effectively combines registration correction and adaptive weight mapping, ensuring geometric alignment and transformation consistency between SAR and optical domains.

- The adaptive weight map integrates attribution and uncertainty information to emphasize reliable regions and reduce the influence of uncertain areas during training, thereby enhancing structural preservation and spectral realism.

- The experimental results show that AWM-GAN consistently outperforms existing comparison models across all evaluation metrics, demonstrating superior performance in both structural accuracy and color restoration quality.

- By achieving explainability in cross-modal image translation, AWM-GAN introduces the potential for integrating explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) into the field of remote sensing image generation.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We propose a registration enhanced CycleGAN framework that explicitly corrects residual geometric errors in SAR-Optical pairs, improving boundary preservation and geometric reliability.

- We design an attribution and uncertainty guided weight map for adaptive loss re-weighting, which reflects spatially varying importance and confidence, thereby boosting both performance and interpretability.

2. Related Work

2.1. Image-to-Image Translation and SAR-to-Optical

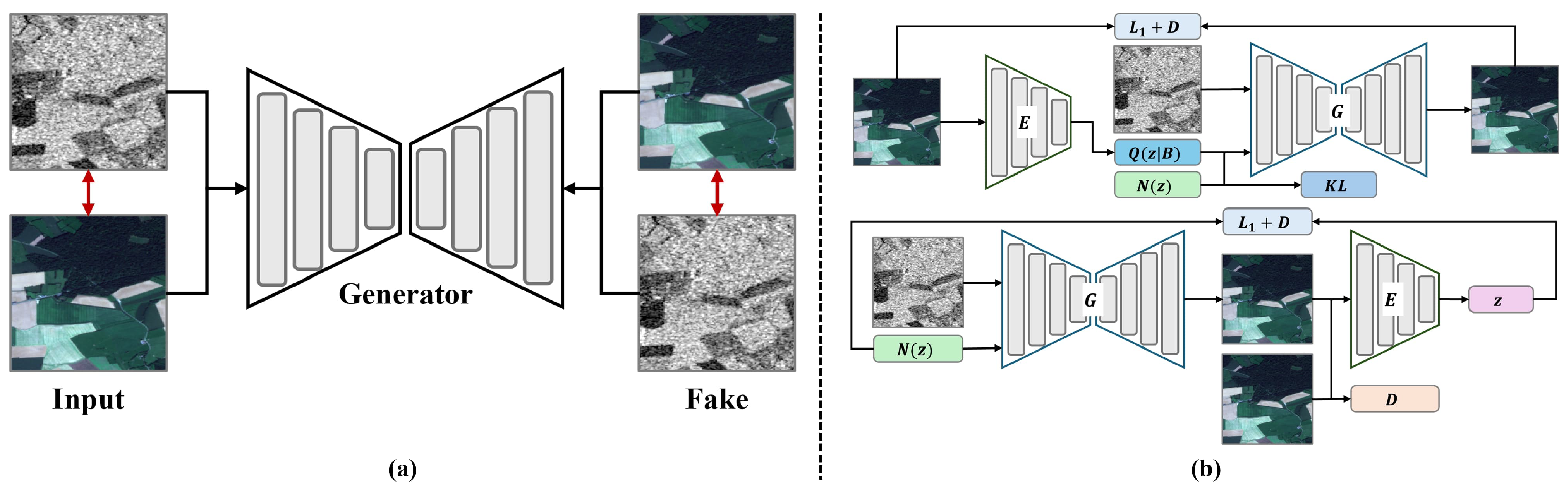

2.1.1. Paired I2I Approaches

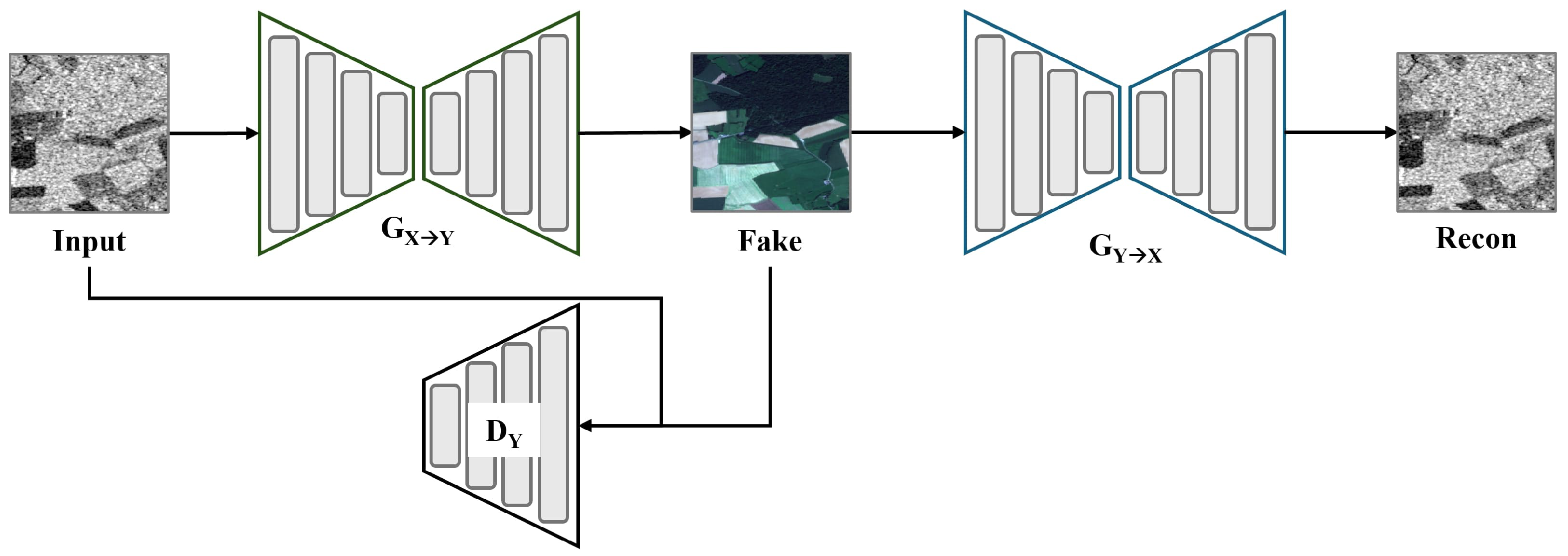

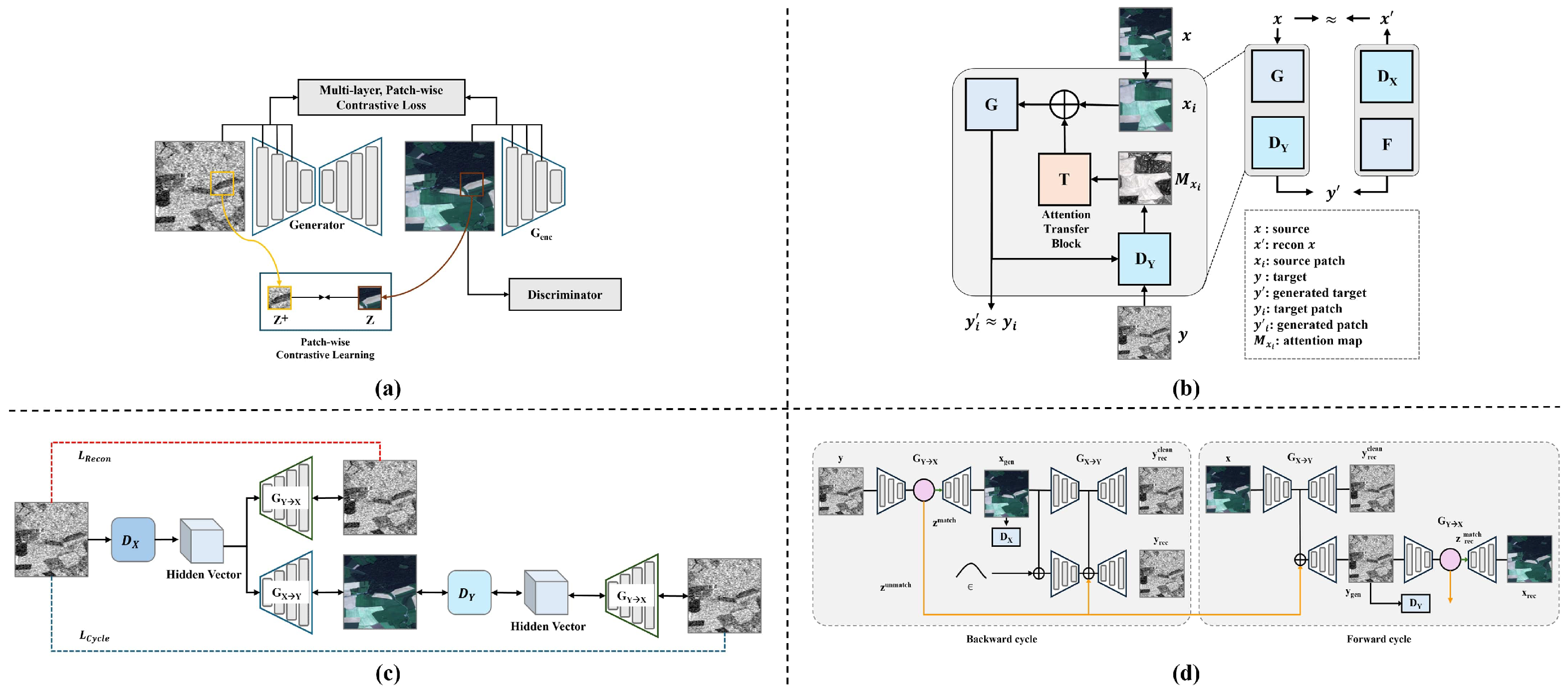

2.1.2. Unpaired I2I Approaches

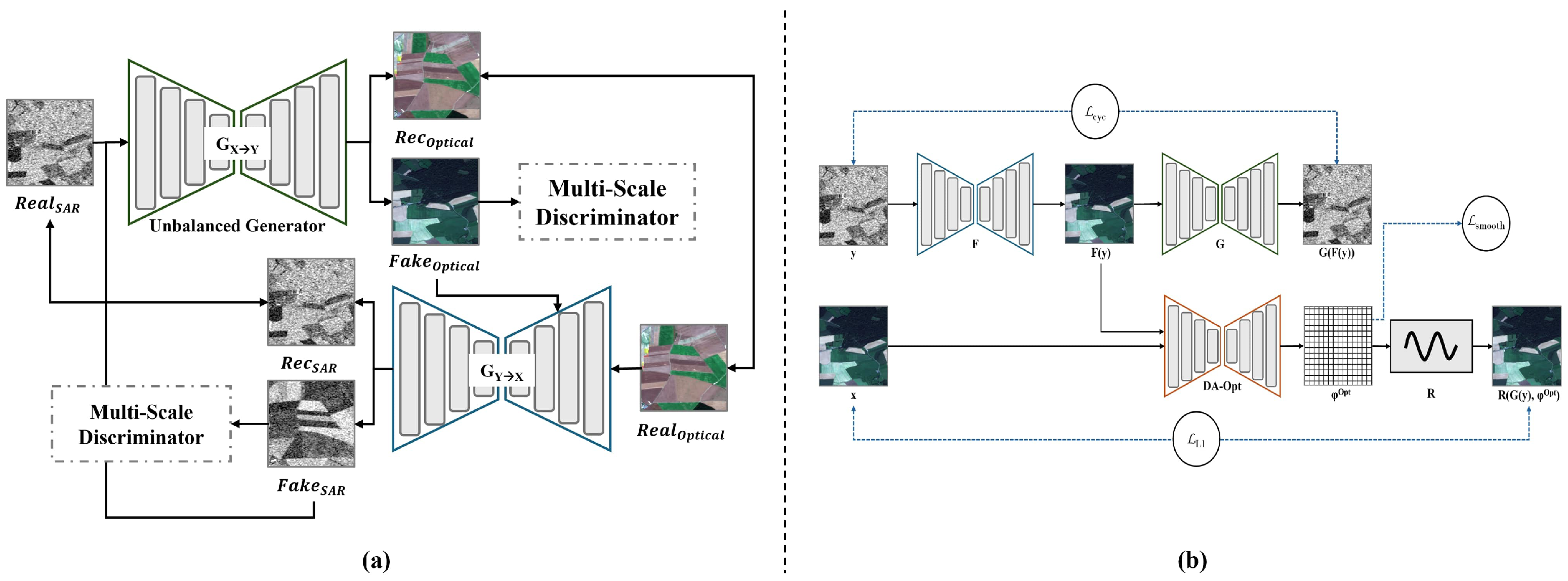

2.1.3. S2O-Specific I2I Approaches

2.2. Attribution and Uncertainty in Vision Translation

3. Data Description

3.1. SEN1-2

3.2. SAR2Opt

4. Preliminaries: Cycle-Consistent Adversarial Networks

5. Methods

5.1. Attribution-Uncertainty Guided Weight Map Generation

5.2. Displacement-Field Flow Estimator

5.3. Weight-Map–Guided Global Loss Reweighting

6. Experiments

6.1. Implementation Details

6.1.1. Dataset Configuration

6.1.2. Training Settings

6.1.3. Evaluation Metrics

- Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR): PSNR measures the fidelity of the reconstructed image with respect to the reference image, based on the ratio between signal power and noise power. Higher values indicate closer resemblance to the ground truth. Since PSNR is based on mean squared error (MSE), it emphasizes overall intensity differences but may not fully reflect perceptual quality.

- Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM): SSIM evaluates structural similarity by incorporating luminance, contrast, and structural information. Unlike PSNR, SSIM captures perceptual structural fidelity, making it more consistent with human visual perception. Values closer to 1 indicate higher structural similarity.

- Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS): LPIPS quantifies perceptual similarity by comparing deep features from pretrained neural networks. It measures the distance between local image patches in feature space, correlating well with human perception. Lower values imply closer perceptual similarity.

- Spectral Angle Mapper (SAM): Widely used in remote sensing, SAM measures the spectral similarity between reconstructed and reference images by computing the angle between spectral vectors. Smaller values indicate better spectral preservation, which is crucial in applications such as land cover and vegetation analysis.

- Relative Global Dimensional Synthesis Error (ERGAS): ERGAS quantifies the overall radiometric distortion between reconstructed and reference images. It is calculated from the normalized root mean square error (RMSE) across spectral bands. Lower values represent higher radiometric consistency.

- CIEDE2000 Color Difference (): Following the International Commission on Illumination (CIE) standard, measures the perceptual difference in color based on hue, chroma, and lightness. It provides a reliable indication of how close the reconstructed image colors are to the ground truth optical image. Lower values denote better color consistency.

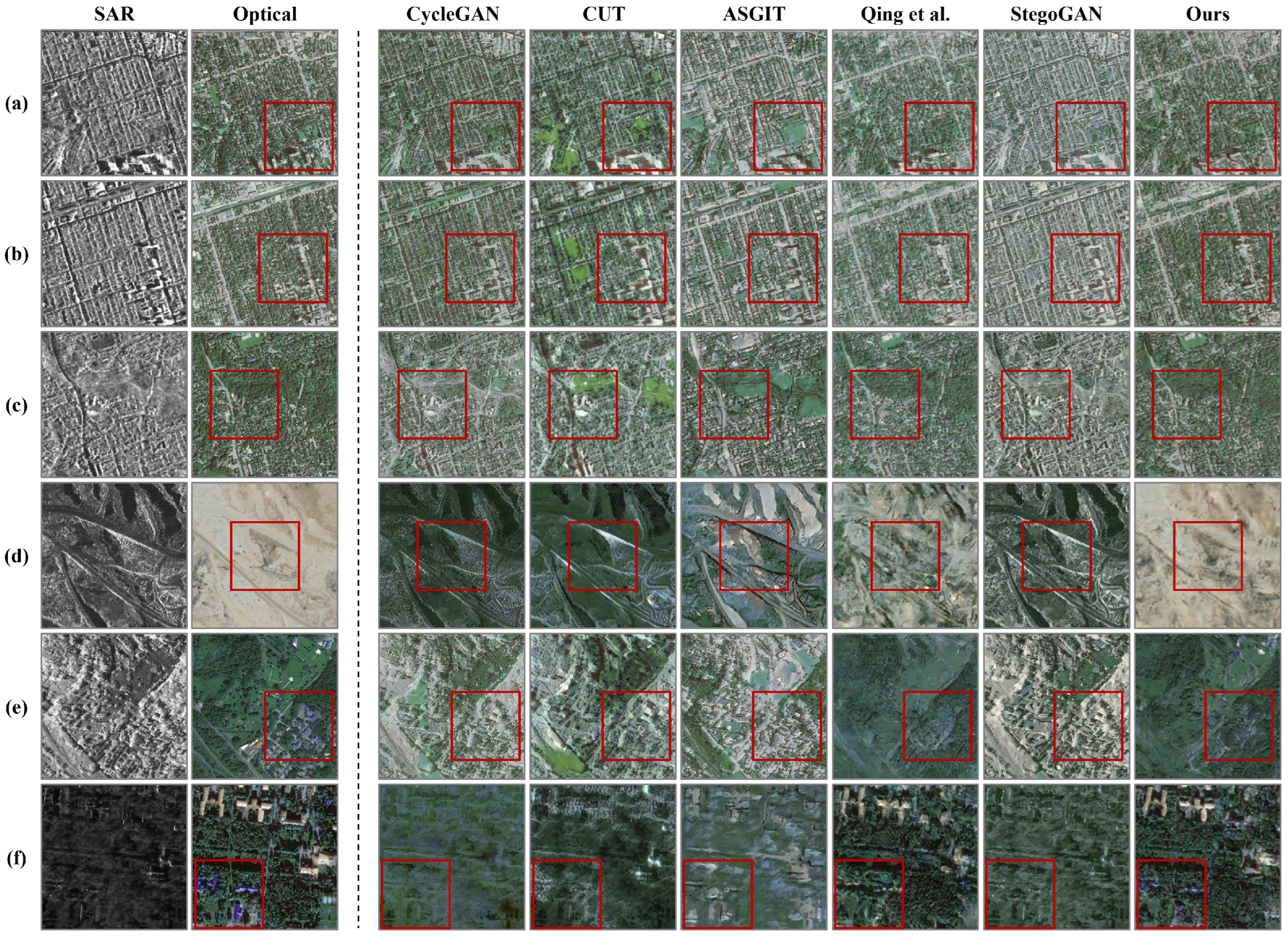

6.2. Qualitative Results

6.3. Quantitative Results

6.3.1. Accuracy-Based Metrics

6.3.2. Computational Cost Analysis

6.4. Ablation Study

7. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tsokas, A.; Rysz, M.; Pardalos, P.M.; Dipple, K. SAR data applications in earth observation: An overview. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 205, 117342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Marino, A.; Ionescu, M.; Gvilava, M.; Savaneli, Z.; Loureiro, C.; Spyrakos, E.; Tyler, A.; Stanica, A. Combining optical and SAR satellite data to monitor coastline changes in the Black Sea. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 226, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, M.G.; Jalilvand, E.; Alemohammad, H.; Tan, P.N.; Das, N.N. Review of synthetic aperture radar with deep learning in agricultural applications. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 218, 20–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Wang, C.; Zhu, J.; Song, D.; Xiang, D.; Fu, H.; Hu, J.; Xie, Q.; Wang, B.; Ren, P.; et al. TVPol-Edge: An Edge Detection Method With Time-Varying Polarimetric Characteristics for Crop Field Edge Delineation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4408917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Yin, X.; Li, Y.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Mao, P.; Jiang, X. High-precision flood mapping from Sentinel-1 dualpolarization SAR data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 4204315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, T.; Weng, X.; Holail, S.; Hao, C.; Xia, G.S. DAM-Net: Flood detection from SAR imagery using differential attention metric-based vision transformers. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 212, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, D.; Song, H.; Fan, C.; Li, K.; Wan, J.; Liu, R. SAR ship detection across different spaceborne platforms with confusion-corrected self-training and region-aware alignment framework. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 228, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, T.; Chang, S.; Deng, Y.; Xue, F.; Wang, C.; Jia, X. Oriented SAR Ship Detection Based on Edge Deformable Convolution and Point Set Representation. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukiou, G. SAR Features and Techniques for Urban Planning—A Review. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Ling, J.; Zhang, H. SoftFormer: SAR-optical fusion transformer for urban land use and land cover classification. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 218, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Gu, Y.; Yu, Q. Dsrkd: Joint despecking and super-resolution of sar images via knowledge distillation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5218613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Liu, R.; Peng, Y.; Guan, J.; Li, D.; Tian, X. Contrastive learning for real SAR image despeckling. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 218, 376–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, D.; Wan, J.; Zheng, C.; Su, J.; Liu, H.; Zhu, H. Source-assisted hierarchical semantic calibration method for ship detection across different satellite SAR images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5215221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Deng, M.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Tang, Q. A sensitive geometric self-calibration method and stability analysis for multiview spaceborne SAR images based on the range-Doppler model. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 220, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Shi, Y.; Ebel, P.; Yu, L.; Xia, G.S.; Yang, W.; Zhu, X.X. GLF-CR: SAR-enhanced cloud removal with global–local fusion. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 192, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Chen, Y.; Huang, B.; Zhu, D.; Lu, T.; Dalla Mura, M.; Chanussot, J. MT_GAN: A SAR-to-optical image translation method for cloud removal. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 225, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xu, Q.; Li, K.; Li, W. DecloudFormer: Quest the key to consistent thin cloud removal of wide-swath multi-spectral images. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 166, 111664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhao, J.; Wei, Z.; Wang, N.; Gao, X. SAR-to-optical image translation based on improved CGAN. Pattern Recognit. 2022, 121, 108208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Pu, X.; Xu, F. Conditional diffusion for SAR to optical image translation. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 21, 4000605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, Y.; Zhu, J.; Feng, H.; Liu, W.; Wen, B. Two-way generation of high-resolution eo and sar images via dual distortion-adaptive gans. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, P.; Zhu, J.Y.; Zhou, T.; Efros, A.A. Image-to-image translation with conditional adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1125–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.Y.; Zhang, R.; Pathak, D.; Darrell, T.; Efros, A.A.; Wang, O.; Shechtman, E. Toward Multimodal Image-to-Image Translation. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Guyon, I., Luxburg, U.V., Bengio, S., Wallach, H., Fergus, R., Vishwanathan, S., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.Y.; Park, T.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A. Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2223–2232. [Google Scholar]

- Park, T.; Efros, A.A.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, J.Y. Contrastive learning for unpaired image-to-image translation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 319–345. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.; Huang, W.; Huang, B.; Sun, F.; Fang, B. Reusing discriminators for encoding: Towards unsupervised image-to-image translation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 8168–8177. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Khan, L. Attention-based spatial guidance for image-to-image translation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Virtual, 5–9 January 2021; pp. 816–825. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Chen, Y.; Mermet, S.; Hurni, L.; Schindler, K.; Gonthier, N.; Landrieu, L. Stegogan: Leveraging steganography for non-bijective image-to-image translation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 7922–7931. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Yang, D. FG-GAN: A fine-grained generative adversarial network for unsupervised SAR-to-optical image translation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5621211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Celik, T.; Liu, N.; Li, H.C. A comparative analysis of GAN-based methods for SAR-to-optical image translation. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 3512605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M.; Hughes, L.H.; Zhu, X.X. The SEN1-2 dataset for deep learning in SAR-optical data fusion. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.01569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, A.; Montavon, G.; Lapuschkin, S.; Müller, K.R.; Samek, W. Layer-wise relevance propagation for neural networks with local renormalization layers. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks, Barcelona, Spain, 6–9 September 2016; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 618–626. [Google Scholar]

- Sundararajan, M.; Taly, A.; Yan, Q. Axiomatic attribution for deep networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; PMLR: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 3319–3328. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, A.; Gal, Y. What uncertainties do we need in bayesian deep learning for computer vision? Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5580–5590. [Google Scholar]

- Gal, Y.; Ghahramani, Z. Dropout as a bayesian approximation: Representing model uncertainty in deep learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, New York, NY, USA, 19–24 June 2016; PMLR: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1050–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay, U.; Chen, Y.; Hepp, T.; Gatidis, S.; Akata, Z. Uncertainty-guided progressive GANs for medical image translation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Strasbourg, France, 27 September–1 October 2021; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 614–624. [Google Scholar]

- Klaser, K.; Borges, P.; Shaw, R.; Ranzini, M.; Modat, M.; Atkinson, D.; Thielemans, K.; Hutton, B.; Goh, V.; Cook, G.; et al. A multi-channel uncertainty-aware multi-resolution network for MR to CT synthesis. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthik, E.N.; Cheriet, F.; Laporte, C. Uncertainty estimation in unsupervised MR-CT synthesis of scoliotic spines. IEEE Open J. Eng. Med. Biol. 2023, 5, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vats, A.; Farup, I.; Pedersen, M.; Raja, K. Uncertainty-Aware Regularization for Image-to-Image Translation. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Tucson, AZ, USA, 26 February–6 March 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 3965–3974. [Google Scholar]

| Method | PSNR | SSIM | LPIPS | SAM | ERGAS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CycleGAN [23] | 9.88 | 0.09 | 0.54 | 13.15 | 125.82 | 29.43 |

| CUT [24] | 9.39 | 0.05 | 0.61 | 12.42 | 131.67 | 31.27 |

| ASGIT [26] | 10.62 | 0.12 | 0.54 | 12.16 | 113.69 | 27.39 |

| Qing et al. [20] | 17.26 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 8.25 | 45.84 | 13.38 |

| StegoGAN [27] | 9.07 | 0.05 | 0.57 | 12.28 | 142.76 | 32.39 |

| Ours | 19.02 | 0.45 | 0.29 | 6.78 | 39.00 | 10.96 |

| Method | PSNR | SSIM | LPIPS | SAM | ERGAS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CycleGAN [23] | 13.06 | 0.19 | 0.75 | 7.04 | 60.99 | 20.82 |

| CUT [24] | 13.05 | 0.17 | 0.74 | 6.50 | 60.06 | 19.81 |

| ASGIT [26] | 12.91 | 0.18 | 0.74 | 6.20 | 62.91 | 20.10 |

| Qing et al. [20] | 15.73 | 0.27 | 0.71 | 5.18 | 45.82 | 14.81 |

| StegoGAN [27] | 12.68 | 0.18 | 0.74 | 6.53 | 64.42 | 20.63 |

| Ours | 16.13 | 0.28 | 0.72 | 4.81 | 43.49 | 13.92 |

| Method | Training Time (s) | Inference Time (s) | Trainable Parameters (M) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CycleGAN [23] | 22,421.8 | 186.65 | 28.29 |

| CUT [24] | 23,108.8 | 80.89 | 14.70 |

| ASGIT [26] | 15,930.5 | 42.17 | 28.29 |

| Qing et al. [20] | 20,429.8 | 74.40 | 32.40 |

| StegoGAN [27] | 31,983.7 | 179.28 | 30.06 |

| Ours | 27,848.3 | 32.27 | 32.39 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pyeon, S.-J.; Kim, S.-H.; Shin, H.-K.; Kim, T.; Nam, W.-J. AWM-GAN: SAR-to-Optical Image Translation with Adaptive Weight Maps. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3878. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233878

Pyeon S-J, Kim S-H, Shin H-K, Kim T, Nam W-J. AWM-GAN: SAR-to-Optical Image Translation with Adaptive Weight Maps. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(23):3878. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233878

Chicago/Turabian StylePyeon, Su-Jang, Seong-Heon Kim, Ho-Kyung Shin, Taeheon Kim, and Woo-Jeoung Nam. 2025. "AWM-GAN: SAR-to-Optical Image Translation with Adaptive Weight Maps" Remote Sensing 17, no. 23: 3878. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233878

APA StylePyeon, S.-J., Kim, S.-H., Shin, H.-K., Kim, T., & Nam, W.-J. (2025). AWM-GAN: SAR-to-Optical Image Translation with Adaptive Weight Maps. Remote Sensing, 17(23), 3878. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233878